Abstract

Aims/Introduction

Dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) can be easily obtained from teeth for general orthodontic reasons. We have previously reported the therapeutic effects of DPSC transplantation for diabetic polyneuropathy. As abundant secretomes from DPSCs are considered to play a central role in the improvement of diabetic polyneuropathy, we investigated whether direct injection of DPSC‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM) into hindlimb skeletal muscles ameliorates diabetic polyneuropathy in diabetic rats.

Materials and Methods

DPSCs were isolated from the dental pulp of Sprague–Dawley rats. Eight weeks after the induction of diabetes, DPSC‐CM was injected into the unilateral hindlimb skeletal muscles in both normal and diabetic rats. The effects of DPSC‐CM on diabetic polyneuropathy were assessed 4 weeks after DPSC‐CM injection. To confirm the angiogenic effect of DPSC‐CM, the effect of DPSC‐CM on cultured human umbilical vascular endothelial cell proliferation was investigated.

Results

The administration of DPSC‐CM into the hindlimb skeletal muscles significantly ameliorated sciatic motor/sensory nerve conduction velocity, sciatic nerve blood flow and intraepidermal nerve fiber density in the footpads of diabetic rats. We also showed that DPSC‐CM injection significantly increased the capillary density of the skeletal muscles, and suppressed pro‐inflammatory reactions in the sciatic nerves of diabetic rats. Furthermore, an in vitro study showed that DPSC‐CM significantly increased the proliferation of umbilical vascular endothelial cells.

Conclusions

We showed that DPSC‐CM injection into hindlimb skeletal muscles has a therapeutic effect on diabetic polyneuropathy through neuroprotective, angiogenic and anti‐inflammatory actions. DPSC‐CM could be a novel cell‐free regenerative medicine treatment for diabetic polyneuropathy.

Keywords: Dental pulp stem cell, Diabetic neuropathy, Regenerative medicine

Introduction

The onset and progression of diabetic polyneuropathy are fundamentally linked to metabolic disorders and blood flow impediments resulting from chronic hyperglycemia, with immune dysfunction as an additional contributing factor1. Painful diabetic neuropathy can now be treated with neurotransmission blockers that produce relatively few adverse reactions, and the options for symptomatic treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy have increased. However, therapeutic strategies targeting the cause of diabetic polyneuropathy are lacking. A particular need exists for radical treatments in cases in which diabetic polyneuropathy has progressed.

Stem cell transplantation is expected to become a novel therapy for diabetic polyneuropathy. We first showed the therapeutic effects of endothelial progenitor cell transplantation for diabetic polyneuropathy2. To date, the efficacy of cell transplantation therapy for diabetic polyneuropathy has been reported by us and others using various kinds of stem cells, such as mesenchymal stem cells and embryonic stem/induced pluripotent‐derived cells3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. These stem cell transplantations improved nerve conduction velocity, nerve blood flow, intraepidermal nerve fiber density, sensory disorders and nerve morphology.

In contrast, cell dysfunction occurred even in progenitor cells and stem cells under diabetic conditions and aging9, 10, 11, 12. The therapeutic efficacy of transplantation of stem cells from aging and/or diabetic animals was impaired compared with that of cells from normal animals13, 14. To solve these problems, we proposed the use of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), a kind of mesenchymal stem cell, for cell transplantation therapy in diabetic polyneuropathy, because DPSCs can be easily isolated from teeth extracted for general orthodontic reasons at young ages, and in many cases before the onset of diabetes, and DPSCs can be cryopreserved until use15.

Initially, researchers expected angiogenesis and neuroprotection to occur as a result of local engrafting and differentiation into multiple cell types. However, subsequent studies showed that very few grafted cells survive at the site of transplantation, which was consistent with most cell therapies for other diseases, such as ischemic heart disease and brain infarction16, 17. Current thinking highlights abundant secretomes from transplanted stem cells, including angiogenic factors, neurotrophic factors and immunosuppressive factors, which might show angiogenic and protective effects at the site of transplantation18, 19. Therefore, we hypothesized that the administration of DPSC‐secreted factors would be a preferable therapy for diabetic polyneuropathy.

In the present study, we used 10× concentrated DPSC‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM), and investigated the therapeutic effects of DPSC‐CM on diabetic polyneuropathy. We first showed that DPSC‐CM administration into unilateral hindlimb skeletal muscles significantly ameliorated nerve conduction velocity, nerve blood flow and intraepidermal nerve fiber density. Our results suggest a cell‐free therapeutic strategy in regenerative medicine for diabetic polyneuropathy.

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats were obtained from Chubu Kagakushizai (Nagoya, Japan) at 6 weeks of age. Streptozotocin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; 60 mg/kg bodyweight in 0.9% sterile saline) was injected intraperitoneally for the induction of diabetes. Rats with a blood glucose level >14 mmol/L were used as diabetic animals. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Aichi Gakuin University (AGUD318), and all animal experiments were carried out following the national guidelines and the relevant national laws on the protection of animals.

Culture of DPSCs and the preparation of DPSC‐CM

Six‐week‐old male Sprague–Dawley rats were killed by an overdose of pentobarbital. Dental pulp tissues from the incisors were collected in one vial; DPSCs were isolated and cultured as previously described15. Collected dental pulp was suspended in phosphate‐buffered saline containing 0.1% collagenase and 0.25% trypsin‐ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. DPSCs were cultured in an alpha modification of Eagle's medium (α‐MEM; GIBCO Laboratories Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA), supplemented with 5.5 mmol/L glucose and 20% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO), on plastic dishes in a humidified incubator at 37°C in 5% CO2. Non‐adherent cells were washed off, and adherent cells were continuously expanded until passage 3.

To obtain DPSC‐CM, DPSCs were maintained in serum‐free Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (GIBCO). After 24 h, the culture medium was collected, concentrated by a factor of 10 using 3‐kDa centrifugal filters (Amicon Ultra‐15; Nihon Millipore, Tokyo, Japan) and frozen at −20°C until use.

Administration of DPSC‐CM

We administered DPSC‐CM into the hindlimb skeletal muscles 8 weeks after streptozotocin injection. DPSC‐CM (1.0 mL/rat) or the same dose of vehicle (Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium) was injected at 10 points in the unilateral hindlimb skeletal muscles of both normal and diabetic rats. Four weeks after administration, the following measurements were carried out.

Sciatic motor and sensory nerve conduction velocities

After anesthetization by isoflurane, motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV) between the ankle and the sciatic notch, and sensory nerve conduction velocity (SNCV) between the ankle and the knee were assessed using a Neuropak MEB‐9400 instrument (Nihon‐Koden, Osaka, Japan). Rats were placed on a warming pad to maintain the near‐nerve temperature at 37°C, monitored by a BAT‐12 multipurpose thermometer (Bioresearch Co., Nagoya, Japan).

Sciatic nerve blood flow

Rats were placed on a warming pad and anesthetized with isoflurane. The femur skin was cut, and a laser probe was placed just above the exposed sciatic nerve. Sciatic nerve blood flow (SNBF) was measured using a Laser Doppler Blood Flow Meter (FLO‐N1; Omega Wave Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Intraepidermal nerve fiber density of the plantar skins

After fixation, footpads were immersed in an optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetechnical, Tokyo, Japan). Then, 25‐μm thick footpad sections were cut on a cryostat. The sections were incubated with anti‐PGP9.5 antibody (Millipore). Alexa Fluor 594‐coupled goat anti‐mouse immunoglobulin G antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was applied as the secondary antibody. Nerve fibers were counted under an FV10i confocal system (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistological staining

Paraffin‐embedded sciatic nerves and gastrocnemius muscles were cut into 5‐μm sections for immunohistochemical staining. The nerve sections were incubated with anti‐CD68 polyclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or anti‐platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM‐1) monoclonal antibody (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and subsequently stained using the Simplestain rat system (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The muscle sections were incubated with anti‐PECAM‐1 monoclonal antibody and stained using an Alexa Fluor 594‐coupled goat anti‐mouse immunoglobulin G antibody (Invitrogen). Slides were observed under light and fluorescence microscope.

Messenger ribonucleic acid expression in sciatic nerves and hindlimb skeletal muscles

Tissues were immersed in RNAlater ribonucleic acid stabilization reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid was synthesized using ReverTra Ace (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). TaqMan Gene Expression Assay primers and probes for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α (tnf), CD68 (CD68), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; vegf) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; fgf2) were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). Real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction was carried out and measured with an ABI Prism 7000 (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantity was calculated with the ΔΔCt method using β2 microglobulin as the endogenous control.

Cell proliferation assay in human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). HUVECs were cultured in EGM‐2 MV complete medium (LONZA; Walkersville, MD, USA). When HUVECs reached 50% confluence in 24‐well dishes, the cells were starved in serum‐free endothelial cell growth medium 2. After starvation, cells were incubated with DPSC‐CM and 3‐(4,5‐di‐methylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma). After a 2‐h incubation, HUVECs were lysed, and the absorbance at 550 nm was read using a spectrophotometer (Spark; TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Another cell proliferation assay was carried out using a Cell Counting Kit‐8 (CCK‐8; Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer's procedure. After starvation, cells were incubated with DPSC‐CM and CCK‐8 for 2 h. For each well, the absorbance at 450 nm was read on a spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis

All group values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was carried out using one‐way anova with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Result

Bodyweights and blood glucose levels

The diabetic rats showed severe hyperglycemia (vehicle‐injected normal rats 4.8 ± 0.7 mmol/L, vehicle‐injected diabetic rats 23.2 ± 7.2 mmol/L; P < 0.01) and significantly reduced bodyweight (vehicle‐injected normal rats 435.0 ± 17.3 g, vehicle‐injected diabetic rats 245.0 ± 56.9 g; P < 0.01). Normal and diabetic rats administered DPSC‐CM did not show significant changes in blood glucose or bodyweight compared with vehicle‐administered normal and diabetic rats (blood glucose: DPSC‐CM‐injected normal rats 4.7 ± 0.5 mmol/L, DPSC‐CM‐injected diabetic rats 20.3 ± 4.8 mmol/L; bodyweight: DPSC‐CM‐injected normal rats 445.0 ± 34.2 g, DPSC‐CM‐injected diabetic rats 214.0 ± 25.1 g).

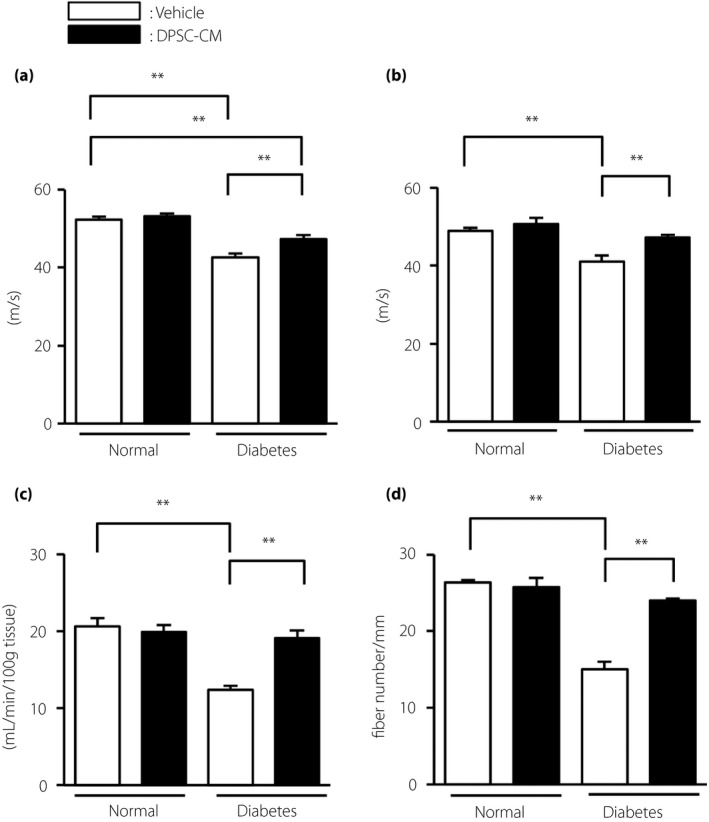

DPSC‐CM improved MNCV, SNCV and SNBF in the diabetic rats

Four weeks after injection with DPSC‐CM, MNCV, SNCV and SNBF were measured. The vehicle‐injected diabetic rats showed significantly delayed MNCV and SNCV, and decreased SNBF compared with the vehicle‐injected normal rats (Figure 1a,b,c; P < 0.01). Notably, DPSC‐CM injection significantly increased MNCV, SNCV and SNBF in the diabetic rats (P < 0.01). In contrast, the administration of DPSC‐DM to normal rats did not affect MNCV, SNCV or SNBF.

Figure 1.

The administration of dental pulp stem cell‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM) improved the delay in sciatic nerve conduction velocities, and the decrease in sciatic nerve blood flow and intraepidermal nerve fiber density in diabetic rats. (a) Sciatic nerve motor nerve conduction velocities. Motor nerve conduction velocity was measured between the ankle and sciatic notch (n = 5–7). (b) Sciatic nerve sensory nerve conduction velocities. Sensory nerve conduction velocity was measured between the ankle and knee (n = 5–7). (c) Sciatic nerve blood flow. Sciatic nerve blood flow was measured using a laser Doppler blood flow meter (n = 5–7). (d) Intraepidermal nerve fiber density of the footpads (n = 4). The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. **P < 0.01. Measurements were carried out 4 weeks after the DPSC‐CM injection.

When we compared these parameters in diabetic rats injected with DPSC‐CM on one side and vehicle on the opposite side, MNCV and SNCV were significantly improved in the DPSC‐CM‐injected side compared with those in the opposite side (Figure S1). SNBF tended to be increased on the DPSC‐CM‐injected side, but this difference was not significant.

DPSC‐CM increased intraepidermal nerve fiber density of the footpads in diabetic rats

Quantitative analyses revealed that the vehicle‐injected diabetic rats showed significantly reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD) compared with the vehicle‐injected normal rats (vehicle‐injected normal rats: 26.3 ± 0.3/mm, vehicle‐injected diabetic rats: 15.0 ± 1.0/mm; P < 0.01; Figure 1d). DPSC‐CM administration significantly increased IENFD in the diabetic rats (24.0 ± 0.2 /mm; P < 0.01), although it did not affect IENFD in the normal rats.

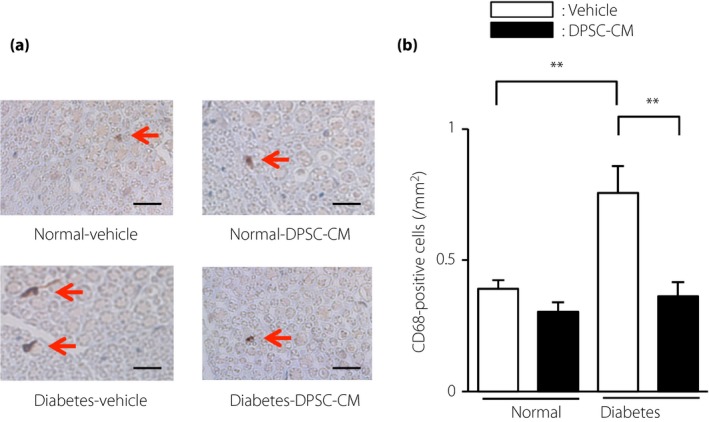

DPSC‐CM suppressed inflammation in the sciatic nerves of diabetic rats

The number of macrophages in the sciatic nerves was visualized by staining with CD68 antibody (Figure 2a). The number of macrophages was significantly increased in the diabetic rats (vehicle‐injected diabetic rats: 0.80 ± 0.10/mm2, vehicle‐injected normal rats: 0.40 ± 0.03/mm2, P < 0.01; Figure 2b). Furthermore, the administration of DPSC‐CM to the diabetic rats significantly suppressed the number of macrophages in the sciatic nerves (0.40 ± 0.05/mm2, P < 0.01). However, no significant difference was observed between the vehicle‐injected and DPSC‐CM‐injected normal rats.

Figure 2.

Dental pulp stem cell‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM) injection suppressed the number of CD68‐positive macrophages in sciatic nerves of diabetic rats. (a) Representative photomicrographs of the sciatic nerves of normal and diabetic rats injected with vehicle or DPSC‐CM. Macrophages were detected by immunostaining for CD68. Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) Quantitative analyses of CD68‐positive cells/mm2 in the sciatic nerves of normal and diabetic rats (n = 4). The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. **P < 0.01.

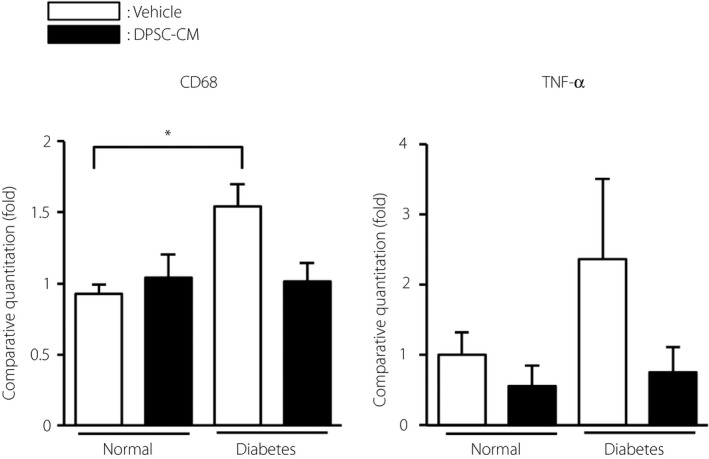

We confirmed that the gene expression of CD68 was significantly increased in the sciatic nerves of diabetic rats (P < 0.05), and was ameliorated by the administration of DPSC‐CM (Figure 3). An increasing trend of expression of the pro‐inflammatory gene, TNF‐α, was also seen in the sciatic nerves of diabetic rats, although this increase was not significant. DPSC‐CM did not affect CD68 and TNF‐α gene expression in the normal rats.

Figure 3.

The effects of dental pulp stem cell‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM) on the inflammatory messenger ribonucleic acid expressions in sciatic nerves of normal and diabetic rats. Four weeks after the injection of DPSC‐CM, the messenger ribonucleic acid expression of CD68 (CD68) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF‐α; Tnf) in the sciatic nerves was evaluated by real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (n = 4–6). The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05.

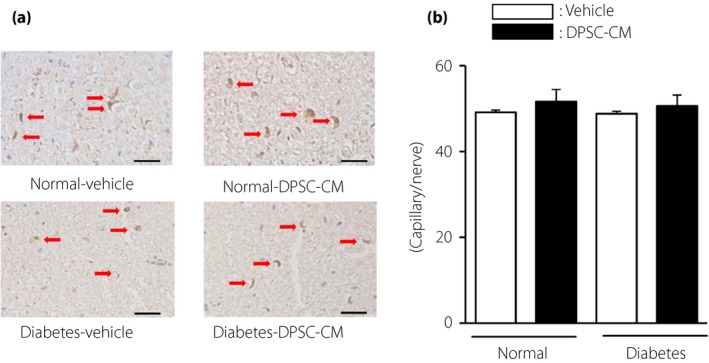

Number of capillaries in sciatic nerves was unaffected by DPSC‐CM

The capillaries were visualized by staining with PECAM‐1 antibody (Figure 4a). The number of capillaries in sciatic nerves was similar in the normal and diabetic rats (vehicle‐injected normal rats: 49.2 ± 0.5, vehicle‐injected diabetic rats: 48.8 ± 0.6; Figure 4b). The administration of DPSC‐CM into the hindlimb skeletal muscles did not affect the capillary number in sciatic nerves (DPSC‐CM‐injected normal rats: 51.6 ± 2.9, DPSC‐CM‐injected diabetic rats: 50.6 ± 2.6).

Figure 4.

The number of capillaries in sciatic nerves was unaffected by dental pulp stem cell‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM). (a) Representative photomicrographs of immunohistological staining of the sciatic nerves of normal and diabetic rats. Capillaries were visualized with platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1. Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis of the number of capillaries in sciatic nerves of normal and diabetic rats (n = 4). The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

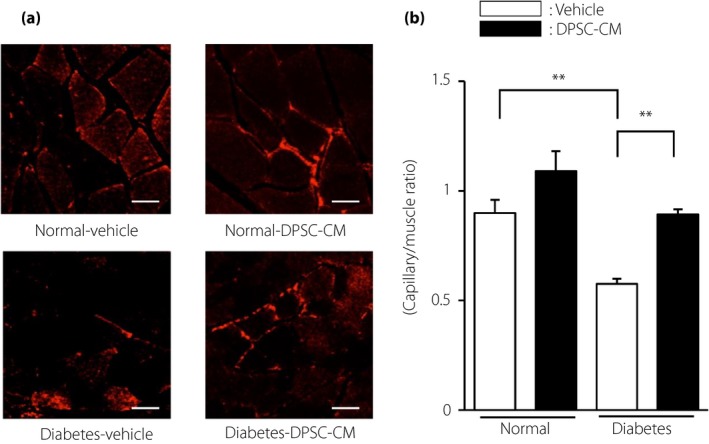

DPSC‐CM increased the capillary density of the hindlimb skeletal muscles in diabetic rats

Capillary density in the hindlimb skeletal muscles was significantly decreased in the diabetic rats (vehicle‐injected diabetic rats: 0.58 ± 0.02, vehicle‐injected normal rats: 0.90 ± 0.06 capillary number/muscle fiber, P < 0.01; Figure 5a,b). Interestingly, DPSC‐CM significantly increased the capillary‐to‐muscle ratio in diabetic rats (DPSC‐CM‐injected diabetic rats: 0.90 ± 0.02 capillary number‐to‐muscle fiber, P < 0.01). The capillary‐to‐muscle ratio in the normal rats was not affected by DPSC‐CM.

Figure 5.

The administration of dental pulp stem cell‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM) increased the capillary density in the hindlimb skeletal muscles of diabetic rats. (a) Representative photomicrographs of immunohistological staining of the skeletal muscles of normal and diabetic rats. Capillaries were visualized with platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1. Scale bar, 50 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis of the capillary‐to‐muscle fiber ratio of the skeletal muscles of normal and diabetic rats (n = 4). The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. **P < 0.01.

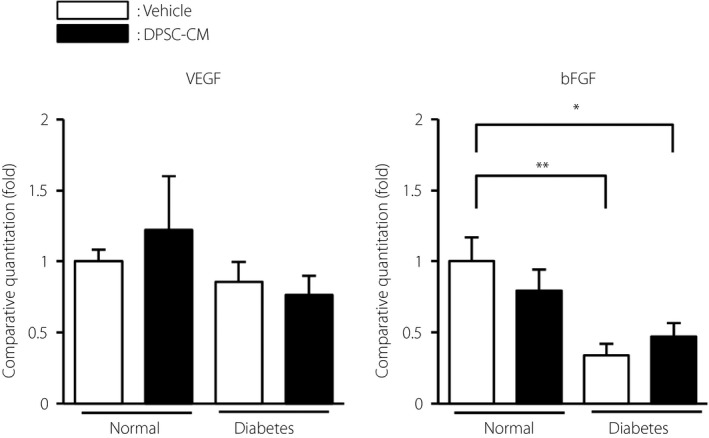

Impact of DPSC‐CM administration on VEGF and bFGF gene expression in the hindlimb skeletal muscles

No significant difference in VEGF gene expression in the hindlimb skeletal muscles was found between the normal and diabetic rats (Figure 6). In contrast, the gene expression levels of bFGF were significantly decreased in the diabetic rats compared with the normal rats (vehicle‐injected diabetic rats: 0.34 ± 0.08 vs vehicle‐injected normal rats, P < 0.01). DPSC‐CM did not change VEGF or bFGF gene expression in the hindlimb skeletal muscles at 4 weeks after injection in either normal or diabetic rats.

Figure 6.

Effects of dental pulp stem cell‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM) on messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the hindlimb skeletal muscles. Four weeks after injection with DPSC‐CM, the messenger ribonucleic acid expression levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in the hindlimb skeletal muscles were evaluated by real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 4–7). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

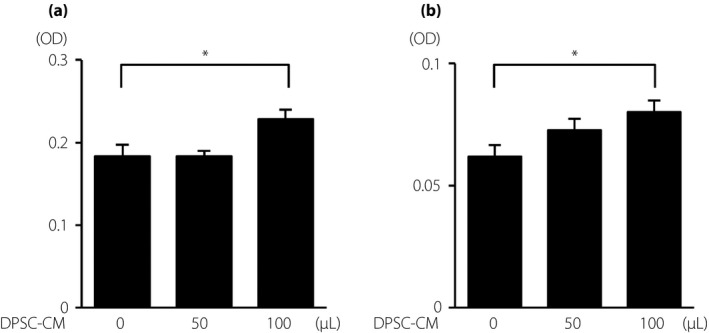

DPSC‐CM increased the proliferation of vascular endothelial cells

We investigated whether DPSC‐CM directly increased the proliferation of HUVECs. Cell proliferation was assessed by CCK‐8 and MTT assays. DPSC‐CM significantly increased the proliferation of HUVECs, as shown by a 1.2‐fold increase by CCK‐8 assay (Figure 7a) and a 1.3‐fold increase by the MTT assay (Figure 7b; P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Dental pulp stem cell‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM) promoted vascular endothelial cell viability. (a) Cell proliferation was assessed by cell counting kit‐8. (b) Cell proliferation was assessed with a 3‐(4,5‐di‐methylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8). *P < 0.05.

Discussion

In the present study, we first showed the therapeutic efficacy of DPSC‐CM on diabetic polyneuropathy. Administration of DPSC‐CM into the hindlimb skeletal muscles significantly ameliorated sciatic MNCV, SNCV and SNBF, as well as IENFD in the footpads of diabetic rats. We also showed that DPSC‐CM injection significantly increased the capillary density of hindlimb skeletal muscles and suppressed the pro‐inflammatory reaction in sciatic nerves of diabetic rats.

We have previously reported the therapeutic effect of DPSC transplantation on diabetic polyneuropathy15, 20, 21. However, many of the engrafted DPSCs disappeared from the transplanted site during a certain period after transplantation, which is consistent with other cell transplantation therapies for ischemic heart disease and brain infarction17, 22. Therefore, we hypothesized that the therapeutic mechanisms of stem cell transplantation were mainly associated with the abundant secretomes of transplanted stem cells in the early phase of transplantation. In the present study, a single injection of DPSC‐CM into the hindlimb skeletal muscles ameliorated diabetic polyneuropathy by promoting the recovery of sciatic MNCV and SNCV, and the increase in IENFD of diabetic rats. Furthermore, DPSC‐CM administration reduced the number of macrophages in the sciatic nerves of diabetic rats.

When we compare the therapeutic effects between DPSC‐CM administration in the present study and DPSC transplantation in our previous study, the effects of DPSC‐CM administration on SNCV and SNBF were comparable to those of DPSC transplantation15. However, the effect of DPSC‐CM for MNCV was lower than that of DPSC transplantation (data not shown). We will investigate the doses and timing of DPSC‐CM administration to improve efficacy in the future.

We previously confirmed the gene expression of angiogenic factors, neurotrophic factors and immunomodulatory factors in cultured DPSCs20. Under inflammatory conditions, DPSC‐CM increased the anti‐inflammatory marker genes, CD206 and interleukin‐10, in macrophages and induced M2 polarization20. In neuronal cells, DPSC‐CM elongated neurite outgrowth of dorsal root ganglion cells, and increased the proliferation and myelin formation of Schwann cells21.

A previous study showed decreased capillary density in skeletal muscles in diabetic patients23. We showed that DPSC‐CM improved the decrease in capillary density in the skeletal muscles of diabetic rats. This phenomenon might be due to the direct angiogenic effects of DPSC‐CM, as DPSC‐CM contains abundant VEGF21 and significantly increases the viability of HUVECs in culture. However, the direct relationship between capillary density in the skeletal muscles and diabetic neuropathy is still unclear. Just a few studies have investigated the relationship between capillary density in skeletal muscles and diabetic neuropathy. Andreassen et al.24 showed no relationship between capillary density and the degree of neuropathy. However, the sample size was not large enough in that study.

We observed the decrease of nerve blood flow in the diabetic rats, which was ameliorated by DPSC‐CM administration. In contrast, the capillary number in the sciatic nerves was similar between the normal and diabetic rats, and DPSC‐CM administration did not affect the capillary number in sciatic nerves. As the major morphological changes in the capillaries in the peripheral nerves of diabetes patients are basement membrane thickness, vascular endothelial cell hyperplasia and reduction in lumen area25, 26, DPSC‐CM might affect them. Further study is required in this field.

Because DPSC‐CM contains VEGF, we must consider the risk of diabetic retinopathy. Thus far, the risk of worsening diabetic retinopathy by DPSC‐CM administration to the lower limb does not seem high, because a clinical trial for diabetic polyneuropathy showed that VEGF gene transfer to the legs did not show worse proliferative retinopathy27. However, selecting patients without proliferative retinopathy and monitoring diabetic retinopathy in the case of DPSC‐CM administration might be necessary to avoid the risk of worsening diabetic retinopathy.

The therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell‐conditioned media have been explored in other diseases, such as ischemic heart disease28, brain injury29, spinal cord injury30 and bone defects31. The use of cell‐free therapies, such as conditioned media from mesenchymal stem cells, has specific advantages over stem cell‐based therapies. First, conditioned media was free from graft versus host disease, tumorigenicity and embolus formation32. Second, large‐scale production of conditioned media reduces the cost and maintains the high quality of conditioned media. Third, treatment for acute conditions, such as ischemic heart disease and brain infarction, is immediately available. In addition, the advantage of DPSC‐CM is that we can continuously obtain young and high‐quality DPSCs from teeth extracted for general orthodontic reasons at young ages and, in many cases, before the onset of several diseases without further invasion.

We used 10‐fold concentrated DPSC‐CM using a 3‐kDa filter for protein. Because the main proteins of the angiogenic, neurotrophic and immunomodulated factors are larger than 3‐kDa (e.g., VEGF, bFGF, nerve growth factor [NGF], neurotrophin [NT]‐3 and macrophage colony‐stimulating factor; gene expression of all of these has been confirmed in DPSCs20), this method is useful for reducing the administration volume without loss of efficacy. The combination of angiogenic, neurotrophic and immunomodulatory effects might show multifocal improvement of diabetic polyneuropathy. VEGF gene transfer to the lower limbs increased vascularity and improved symptoms of diabetic polyneuropathy27, 33. bFGF has angiogenic and neurotrophic effects, and we previously showed that intramuscular administration of bFGF with cross‐linked gelatin hydrogel improved SNCV and SNBF in diabetic rats34. Neurotrophic factors, such as NGF and NT‐3, are reduced in diabetic animals35, 36. NGF binds to p75 and tropomyosin receptor kinase A with effects on small sensory and autonomic nerve fibers. In contrast, NT‐3 binds to tropomyosin receptor kinase C, which is expressed in the large fibers. Although clinical trials with NGF were unsuccessful, many animal studies showed the prevention of pain sensation reduction37, 38. NT‐3 prevented abnormalities in neurofilament biology and mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic animals39, 40. Macrophage colony‐stimulating factor promoted macrophage polarization toward the anti‐inflammatory M2 type41. Furthermore, macrophage migration and activation were increased in the sciatic nerves in diabetic rats42, 43. Our previous study confirmed that DPSC‐CM promoted M2 polarization in lipopolysaccharide‐stimulated RAW264.7 cells20.

We used a single injection of DPSC‐CM, and carried out an analysis 4 weeks post‐injection in the present study. However, we need to further investigate the doses and timing of DPSC‐CM injections, as well as the duration of efficacy in future experiments.

In conclusion, we showed that DPSC‐CM injection into hindlimb skeletal muscles has therapeutic effects on diabetic polyneuropathy through neuroprotective, angiogenic and anti‐inflammatory actions. In comparison with stem cell transplantation, the use of DPSC‐CM will lead to a reduction in medical costs, maintenance of DPSC‐CM quality by using selected DPSCs with high viability, and freedom from immune incompatibility and tumorigenicity. These advantages will extend DPSC‐CM injection therapy as a treatment for diabetic polyneuropathy.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1 | The comparison of neurophysiological parameters between the dental pulp stem cell‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM)‐injected side and vehicle‐injected opposite side in the diabetic rats.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (21592506) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).

J Diabetes Investig 2019; 10: 1199–1208

References

- 1. Yagihashi S, Mizukami H, Sugimoto K. Mechanism of diabetic neuropathy: where are we now and where to go? J Diabetes Investig 2011; 2: 18–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Naruse K, Hamada Y, Nakashima E, et al Therapeutic neovascularization using cord blood‐derived endothelial progenitor cells for diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes 2005; 54: 1823–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shibata T, Naruse K, Kamiya H, et al Transplantation of bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells improves diabetic polyneuropathy in rats. Diabetes 2008; 57: 3099–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Okawa T, Kamiya H, Himeno T, et al Transplantation of neural crest‐like cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells improves diabetic polyneuropathy in mice. Cell Transplant 2013; 22: 1767–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Himeno T, Kamiya H, Naruse K, et al Angioblast derived from ES cells construct blood vessels and ameliorate diabetic polyneuropathy in mice. J Diabetes Res 2015; 2015: 257230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Han JW, Choi D, Lee MY, et al Bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells improve diabetic neuropathy by direct modulation of both angiogenesis and Myelination in peripheral nerves. Cell Transplant 2016; 25: 313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Monfrini M, Donzelli E, Rodriguez‐Menendez V, et al Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Exp Neurol 2017; 288: 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Datta I, Bhadri N, Shahani P, et al Functional recovery upon human dental pulp stem cell transplantation in a diabetic neuropathy rat model. Cytotherapy 2017; 19: 1208–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tepper OM, Galiano RD, Capla JM, et al Human endothelial progenitor cells from type II diabetics exhibit impaired proliferation, adhesion, and incorporation into vascular structures. Circulation 2002; 106: 2781–2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Loomans CJ, de Koning EJ, Staal FJ, et al Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of vascular complications of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2004; 53: 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou S, Greenberger JS, Epperly MW, et al Age‐related intrinsic changes in human bone‐marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells and their differentiation to osteoblasts. Aging Cell 2008; 7: 335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baker N, Boyette LB, Tuan RS. Characterization of bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells in aging. Bone 2015; 70: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kondo M, Kamiya H, Himeno T, et al Therapeutic efficacy of bone marrow‐derived mononuclear cells in diabetic polyneuropathy is impaired with aging or diabetes. J Diabetes Investig 2015; 6: 140–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim H, Han JW, Lee JY, et al Diabetic mesenchymal stem cells are ineffective for improving limb ischemia due to their impaired angiogenic capability. Cell Transplant 2014; 8: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hata M, Omi M, Kobayashi Y, et al Transplantation of cultured dental pulp stem cells into the skeletal muscles ameliorated diabetic polyneuropathy: therapeutic plausibility of freshly isolated and cryopreserved dental pulp stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2015; 6: 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toma C, Pittenger MF, Cahill KS, et al Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation 2002; 105: 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu X, Xu Y, Zhong Z, et al A Large‐scale investigation of hypoxia‐preconditioned allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for myocardial repair in nonhuman primates: paracrine activity without Remuscularization. Circ Res 2016; 118: 970–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gnecchi M, Zhang Z, Ni A, et al Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res 2008; 103: 1204–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chimenti I, Smith RR, Li TS, et al Relative roles of direct regeneration versus paracrine effects of human cardiosphere‐derived cells transplanted into infarcted mice. Circ Res 2010; 106: 971–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Omi M, Hata M, Nakamura N, et al Transplantation of dental pulp stem cells suppressed inflammation in sciatic nerves by promoting macrophage polarization towards anti‐inflammation phenotypes and ameliorated diabetic polyneuropathy. J Diabetes Investig 2016; 7: 485–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Omi M, Hata M, Nakamura N, et al Transplantation of dental pulp stem cells improves long‐term diabetic polyneuropathy together with improvement of nerve morphometrical evaluation. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017; 8: 279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garbuzova‐Davis S, Haller E, Lin R, et al Intravenously transplanted human bone marrow endothelial progenitor cells engraft within brain capillaries, preserve mitochondrial morphology, and display Pinocytotic activity toward blood‐brain barrier repair in ischemic stroke rats. Stem Cells 2017; 35: 1246–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Groen BB, Hamer HM, Snijders T, et al Skeletal muscle capillary density and microvascular function are compromised with aging and type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol 2014; 116: 998–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Andreassen CS, Jensen JM, Jakobsen J, et al Striated muscle fiber size, composition, and capillary density in diabetes in relation to neuropathy and muscle strength. J Diabetes 2014; 6: 462–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Malik R, Newrick P, Sharma A, et al Microangiopathy in human diabetic neuropathy: relationship between capillary abnormalities and the severity of neuropathy. Diabetologia 1989; 32: 92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yasuda H, Dyck PJ. Abnormalities of endoneurial microvessels and sural nerve pathology in diabetic neuropathy. Neurology 1987; 37: 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ropper AH, Gorson KC, Gooch CL, et al Vascular endothelial growth factor gene transfer for diabetic polyneuropathy: a randomized, double‐blinded trial. Ann Neurol 2009; 65: 386–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Timmers L, Lim SK, Hoefer IE, et al Human mesenchymal stem cell‐conditioned medium improves cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res 2011; 6: 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang CP, Chio CC, Cheong CU, et al Hypoxic preconditioning enhances the therapeutic potential of the secretome from cultured human mesenchymal stem cells in experimental traumatic brain injury. Clin Sci 2013; 124: 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cantinieaux D, Quertainmont R, Blacher S, et al Conditioned medium from bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells improves recovery after spinal cord injury in rats: an original strategy to avoid cell transplantation. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e69515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Katagiri W, Osugi M, Kinoshita K, et al Conditioned medium from mesenchymal stem cells enhances early bone regeneration after maxillary sinus floor elevation in rabbits. Implant Dent 2015; 24: 657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vizoso FJ, Eiro N, Cid S, et al Mesenchymal stem cell secretome: toward cell‐free therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18: 1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Makinen K, Manninen H, Hedman M, et al Increased vascularity detected by digital subtraction angiography after VEGF gene transfer to human lower limb artery: a randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blinded phase II study. Mol Ther 2002; 6: 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakae M, Kamiya H, Naruse K, et al Effects of basic fibroblast growth factor on experimental diabetic neuropathy in rats. Diabetes 2006; 55: 1470–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steinbacher BC Jr, Nadelhaft I. Increased levels of nerve growth factor in the urinary bladder and hypertrophy of dorsal root ganglion neurons in the diabetic rat. Brain Res 1998; 782: 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kamiya H, Murakawa Y, Zhang W, et al Unmyelinated fiber sensory neuropathy differs in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2005; 21: 448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Apfel SC, Schwartz S, Adornato BT, et al Efficacy and safety of recombinant human nerve growth factor in patients with diabetic polyneuropathy: a randomized controlled trial. rhNGF Clinical Investigator Group. JAMA 2000; 284: 2215–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Apfel SC, Arezzo JC, Brownlee M, et al Nerve growth factor administration protects against experimental diabetic sensory neuropathy. Brain Res 1994; 634: 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sayers NM, Beswick LJ, Middlemas A, et al Neurotrophin‐3 prevents the proximal accumulation of neurofilament proteins in sensory neurons of streptozocin‐induced diabetic rats. Diabetes 2003; 52: 2372–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang TJ, Sayers NM, Verkhratsky A, et al Neurotrophin‐3 prevents mitochondrial dysfunction in sensory neurons of streptozotocin‐diabetic rats. Exp Neurol 2005; 194: 279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fleetwood AJ, Lawrence T, Hamilton JA, et al Granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (CSF) and macrophage CSF‐dependent macrophage phenotypes display differences in cytokine profiles and transcription factor activities: implications for CSF blockade in inflammation. J Immunol 2007; 178: 5245–5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nukada H, McMorran PD, Baba M, et al Increased susceptibility to ischemia and macrophage activation in STZ‐diabetic rat nerve. Brain Res 2011; 1373: 172–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yamagishi S, Ogasawara S, Mizukami H, et al Correction of protein kinase C activity and macrophage migration in peripheral nerve by pioglitazone, peroxisome proliferator activated‐gamma‐ligand, in insulin‐deficient diabetic rats. J Neurochem 2008; 104: 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 | The comparison of neurophysiological parameters between the dental pulp stem cell‐conditioned media (DPSC‐CM)‐injected side and vehicle‐injected opposite side in the diabetic rats.