Abstract

The presence of biomaterials and devices implanted into soft tissue is associated with development of a foreign body response (FBR), a chronic inflammatory condition that can ultimately lead to implant failure, which may cause harm to or death of the patient. Development of FBR includes activation of macrophages at the tissue-implant interface, generation of destructive foreign body giant cells (FBGCs), and generation of fibrous tissue that encapsulates the implant. However, the mechanisms underlying the FBR remain poorly understood, as neither the materials composing the implants nor their chemical properties can explain triggering of the FBR. Herein, we report that genetic ablation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4), a Ca2+-permeable mechanosensitive cation channel in the transient receptor potential vanilloid family, protects TRPV4 knockout mice from FBR-related events. The mice showed diminished collagen deposition along with reduced macrophage accumulation and FBGC formation compared with wild-type mice in a s.c. implantation model. Analysis of macrophage markers in spleen tissues and peritoneal cavity showed that the TRPV4 deficiency did not impair basal macrophage maturation. Furthermore, genetic deficiency or pharmacologic antagonism of TRPV4 blocked cytokine-induced FBGC formation, which was restored by lentivirus-mediated TRPV4 reintroduction. Taken together, these results suggest an important, previously unknown, role for TRPV4 in FBR.

Biomaterials and medical devices are routinely used in millions of procedures each year, in circumstances such as prostheses in orthopedic, dental, cardiovascular, or reconstructive surgery, in ophthalmologic procedures, in angioplasty and hemodialysis, and as controlled drug release devices.1, 2, 3, 4 However, the insertion of medical devices into soft tissue is associated with the development of foreign body response (FBR), a chronic inflammatory response that is identified by an inner layer of adherent macrophages and/or destructive foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) and an outside layer of fibrotic connective tissue.1, 2, 3, 4 The FBR ultimately leads to structural or functional implant failure because of encapsulation and/or physical degradation, and may cause harm to or death of the patient. The FBR poses a vexing challenge for the bioengineer, clinician, and patient because there are no therapeutic options.1, 2, 3, 4 Despite decades of research, the mechanisms underlying the FBR remain poorly understood.

Macrophages are pivotal to generation and progression of the FBR. They participate in the expression of inflammatory proteins, formation of FBGCs, remodeling of the extracellular matrix, and encapsulation of the implant.4, 5, 6, 7 Previous reports by our group and others have shown that multiple macrophage functions, including phagocytosis, adhesion, and migration, are sensitive to matrix stiffness, suggesting that stiffness may play a role in the FBR.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 The mechanosensitive cation channel transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) is widely expressed in numerous cell types, including macrophages.13, 14, 15, 16 Previous reports by our group and others have documented that TRPV4 is activated by a range of biochemical and physical stimuli, including changes in matrix stiffness, osmolarity, biomechanical stresses, growth factors, and metabolites of arachidonic acid in vitro and in vivo.8, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 TRPV4 is known to participate in numerous physiological functions, including osmolarity sensing in kidneys, sheer-stress detection in arteries, neurologic function, and control of osteogenesis.16, 24, 25, 26, 27 In mice, TRPV4 deletion is linked to altered pressure/vasodilatory responses, osmosensing, sensory and motor neuropathies, and lung and dermal fibrosis.16, 17, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Collectively, these studies suggest a potential role of TRPV4 in FBR, although no studies have determined its contribution in FBR and formation of FBGCs. To address this critical gap, we determined the effect of TRPV4 loss on biomaterial-induced FBR in vivo. In addition, we sought to determine the impact of gain of function or loss of function of TRPV4 on FBGC formation.

Materials and Methods

Cytokines and Reagents

Antibodies against CD68, F4/80, CD11b, and 5D3 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). GSK2193874, GSK1016790A, Giemsa solution, thioglycolate broth, and Masson trichrome staining kit were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Mouse and rabbit anti-goat IgG were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). Mouse IL-4 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Mouse TRPV4 gene-expressing [lenti-TRPV4–green fluorescent protein (GFP)] and control GFP constructs containing lentiviral particles were developed by OriGene (Rockville, MD). Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated IgG, Prolong diamond DAPI, anti-MARCO IgG, Qdot-655, and Qdot-525 were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Animal and Cell Culture

TRPV4 knockout (KO) mice were obtained from Dr. David X. Zhang (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI). The original creator of these mice on a C57BL/6 background was Dr. Makoto Suzuki (Jichi Medical University, Tochigi, Japan).29 Congenic wild-type (WT) mice were collected from from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). All experiments involving animals were performed following Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines approved by the University of Maryland (College Park, MD) review committee. Murine bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) were harvested from 6- to 7-week–old mice, as previously described.8, 30 BMDMs were maintained in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with M-CSF (20 ng/mL) for 7 to 8 days.

FBR Model

The s.c. implantations of mixed cellulose ester (0.45-μm pore size filters, 12 mm2; Millipore, St. Louis, MO) were performed, as described previously.31 Five TRPV4 KO and five control WT mice (both on a C57BL/6 background), aged 10 to 12 weeks, were used for implantations. Each mouse received one implant on each side of the flank (a total of two implants/mouse), and implants were excised en bloc 28 days after implantation and processed for histologic and immunofluorescence analysis following standard protocols.31, 32 Fibrosis development (by Masson trichrome analysis), multinucleated giant cell formation (by Giemsa staining), and macrophage abundance (by staining with CD68 antibody and DAPI) were evaluated in frozen tissue sections.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Analysis

The percentage of F4/80+/CD11b+ macrophages in spleen cell suspensions and peritoneal cavity lavage fluid in the presence and absence of thioglycolate was analyzed by flow cytometry. Positive signals were detected with antibodies against F4/80+/CD11b+; the specificity of antibody binding was confirmed by the use of isotype-matched control antibodies.

FBGC Generation

BMDMs were seeded on Permanox plastic slides (eight-well, Lab-Tek chamber slides; Nunc, Grand Island, NY) at 1 × 105 cells per well. IL-4 and GM-CSF (25 ng/mL) were added, and cells were maintained for 4 to 7 days in the presence or absence of TRPV4 antagonist (GSK2193874) or agonist (GSK1016790A) until cell fusion was maximal. Slides were stained with Giemsa or DAPI. Five images per well were captured for each condition, and the numbers of giant and single-cell nuclei were counted. The percentage of BMDMs involved in fusion was determined from the number of giant cell nuclei (>5 nuclei) divided by the number of total nuclei.31

Fluorescent Labeling of BMDMs by Qdot Nanoparticles

WT or TRPV4 KO BMDMs were labeled with fluorescent Qdot-655 (red) and mixed with fluorescent Qdot-525 (green)–labeled WT or TRPV4 KO BMDMs, followed by stimulation with IL-4 + GM-CSF to induce FBGC formation.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Frozen tissue sections were immunostained for CD68, F4/80, 5D3, and MARCO (1:100), followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibody (1:300). Digital immunofluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ software version 1.52k (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij), and results are presented as integrated density (the product of area and mean gray value).17 DAPI staining was used to identify nuclei.

Lenti-TRPV4-GFP Overexpression

Lentivirus-mediated overexpression of TRPV4 was accomplished using a GFP-conjugated TRPV4 fusion protein that has been functionally validated (lenti-TRPV4-GFP).17 For transduction, BMDMs were transfected with lentivirus encoding lenti-TRPV4-GFP or empty control GFP constructs containing lentiviral particles for 48 hours in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with polybrene (8 μg/mL; Chemicon International, Waltham, MA). Cells were then transferred to RPMI 1640 medium containing IL-4 and GM-CSF (25 ng/mL) for 7 days to induce multinucleated giant cell formation.

Results

The effect of TRPV4 on the FBR in vivo was studied in a well-established s.c. biomaterial implant model in TRPV4 KO mice compared with WT using mixed cellulose ester, a commonly used model implant.32 Twenty-eight days after implant, the amount of collagen deposition in TRPV4 KO mice was fourfold less than in WT mice, suggesting that implant-induced fibrosis development, a hallmark of FBR, was severely attenuated in the absence of TRPV4 (Figure 1, A and B). Implantation of biomaterials stimulates recruitment and accumulation of macrophages on the surface of the implant, which ultimately fuse and generate destructive FBGCs. The number of FBGCs in TRPV4 KO mice was fourfold less than in WT mice, suggesting that implant-induced macrophage fusion, a critical event in FBR, was severely diminished in the absence of TRPV4 (Figure 1, C and D). Because of the presence of tightly aggregated cells in skin tissues, there is a possibility that macrophage aggregation accounts for some of the observed FBGC counts. In addition, macrophage accumulation at the tissue-implant interface in TRPV4 KO mice was fivefold less than in WT mice, suggesting that implant-induced macrophage recruitment and adherence was compromised in the absence of TRPV4 (Figure 1, E and F). Collectively, our findings of diminished collagen deposition, reduced macrophage accumulation, and reduced FBGC formation show that TRPV4 KO mice were protected from developing FBR (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) deletion in mice prevents macrophage accumulation, foreign body giant cell (FBGC) formation, and collagen accumulation in a s.c. implantation model. Images of sections of filters (asterisks) implanted subcutaneously for 28 days in wild-type (WT) and TRPV4 knockout (KO) mice are shown. A: Sections were stained with Masson trichrome to show deposition of collagen (blue). Red asterisks indicate tissue-implant interface. B: Quantification of collagen in experiment shown in A. C: FBGCs were stained by hematoxylin and eosin. Black arrows indicate presence of FBGCs in sections of implants from WT mice. Red asterisks indicate tissue-implant interface. D: Quantification of FBGC numbers from experiment shown in C. E: Sections were stained with CD68 IgG and visualized with Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated secondary IgG (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Yellow arrows indicate presence of macrophages at tissue-implant interface. White asterisks indicate tissue-implant interface. F: Quantification of macrophage accumulation in experiment shown in E. n = 5 mice per group (A, C, E). ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001 (t-test). Scale bars = 50 μm (A, C, E). HPF, high-power field.

Diminished macrophage maturation in the absence of TRPV4 could potentially account for the reduced FBGC formation and macrophage accumulation in our implantation model. Therefore, the presence of macrophage markers was analyzed in spleen tissues by immunofluorescence. The macrophage markers CD68, EMRI (F4/80), 5D3 (mannose receptor), and MARCO (ED31) were present at the expected levels in spleen of both TRPV4 KO and WT mice, suggesting that the absence of TRPV4 did not impair basal macrophage maturation (Figure 2, A and B). In addition, the distribution of macrophages in the spleen and peritoneum was analyzed in the presence and absence of thioglycolate by flow cytometry. The abundance of F4/80+/CD11b+ macrophages was unaffected in TRPV4 KO splenic, resident-peritoneal, and thioglycolate-induced macrophages (Figure 2C). All together, these results suggest that TRPV4 deficiency does not impair basal macrophage maturation.

Figure 2.

Basal macrophage differentiation is normal in transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4)–deficient mice. A: Sections of spleens from wild-type (WT) and TRPV4 knockout (KO) mice were stained with antibodies for CD68 (FA11), F4/80 (EMRI), 5D3 (mannose receptor), and ED31 (MARCO); nuclei were stained with DAPI. Staining by secondary antibody in the absence of primary antibody was used as IgG control (cont.). B: Quantification of macrophage abundance. C: Percentages of F4/80+/CD11b+ double-positive cells were assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Cells were collected from the peritoneal cavity [resident peritoneal macrophages (ResMΦ)], the spleen [spleen macrophages (SpleenMΦ)], and the peritoneal space of thioglycolate-injected mice [thioglycolate macrophages (ThioMΦ)]. Data are expressed as means ± SD (B and C). n = 5 mice per group (B); n = 3 animals (C). Scale bars = 50 μm.

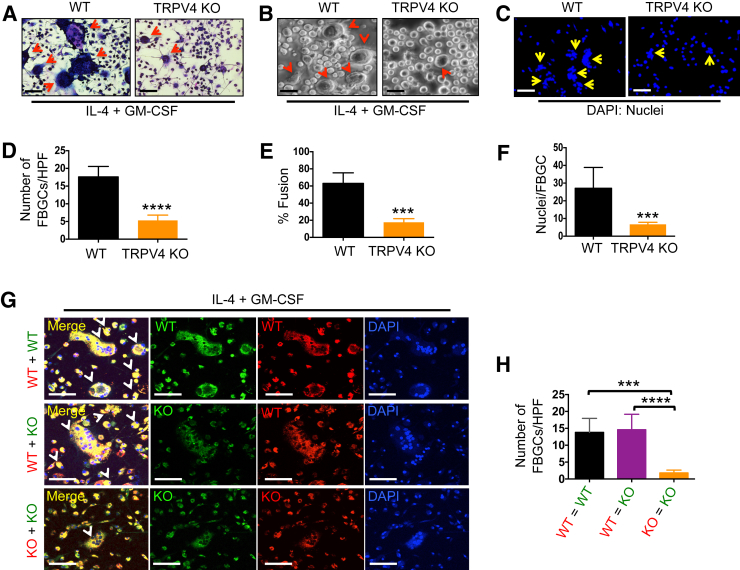

Macrophages play a central role in the development of FBR by participating in the formation of multinucleated FBGCs and by eliciting inflammatory responses.4, 5, 6, 7 Because FBGC formation in vivo was severely diminished in the absence of TRPV4, the IL-4 + GM-CSF–induced FBGC formation assay33 was used to examine the formation of FBGCs in vitro to ascertain if TRPV4 was required for FBGC formation. The degree of macrophage fusion in TRPV4 KO BMDMs was significantly impaired relative to WT BMDMs; FBGCs were reduced fourfold, cell fusion was reduced threefold, and nuclei of single cells were reduced sixfold (Figure 3, A–F). These results suggest that TRPV4 participates in macrophage fusion. It was next examined whether expression of TRPV4 was required for all BMDMs participating in formation of an FBGC. WT or TRPV4 KO BMDMs were labeled with red-fluorescent Qdot-655 and mixed with green-fluorescent Qdot-525–labeled WT or TRPV4 KO BMDMs. Cell fusion was induced by the stimulation with IL-4 + GM-CSF. TRPV4 KO BMDMs were capable of fusing with WT BMDMs, as displayed by the generation of FBGCs that incorporated both the red and green fluorescent labels, therefore appearing yellow in the merged image (Figure 3, G and H). These results suggest that TRPV4 is required on only one fusion partner to form a giant cell.

Figure 3.

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) deficiency results in impaired macrophage fusion. Bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) from wild-type (WT) and TRPV4 knockout (KO) mice were stimulated with IL-4 + granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for 6 days to induce macrophage fusion and foreign body giant cell (FBGC) formation. A: Giemsa staining shows the presence of multinucleated FBGCs (arrows). B: Bright-field images. C: DAPI staining of nuclei. D–F: Quantification of data from experiment shown in A–C. D: Number of FBGCs per high-power field (HPF). E: Percentage macrophage fusion. F: Nuclei per FBGC. G: WT and TRPV4 KO BMDMs were labeled with red-fluorescent Qdot-655 or green-fluorescent Qdot-525 nanoparticles, and fusion was induced by stimulation with IL-4 + GM-CSF. Fusion of macrophages is represented by colocalization of the red and green fluorescent labels (yellow). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). H: Quantitation of colocalization. Red, yellow, or white arrows indicate presence of FBGCs. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (D–F and H). n = 3 independent experiments (A–C, G). ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P ≤ 0.0001 (t-test). Scale bars = 100 μm (A–C and G).

To assess whether attenuation of FBGC formation seen in TRPV4 KO BMDMs was directly related to TRPV4 activity, a gain-of-function or loss-of-function approach was used, as previously described.17 To generate loss of function, TRPV4 activity was blocked in BMDMs using a TRPV4-specific small-molecule chemical inhibitor, GSK2193874.24 Macrophage fusion in GSK2193874-treated BMDMs was significantly impaired compared with vehicle-treated control cells, as determined by quantitation of FBGCs, cell fusion, and nuclei of single cells (Figure 4, A–C). Gain of function was achieved by two approaches: stimulation of TRPV4 activity in BMDMs using the TRPV4-specific agonist, GSK1016790A24; and overexpression of TRPV4 in TRPV4 KO BMDMs by transfection with a lenti-TRPV4-GFP fusion construct or with an empty GFP vector control.17 Treatment of BMDMs with GSK1016790A increased the amount of cell fusion compared with vehicle-treated control cells (Figure 4, D–H). It was found that overexpression of TRPV4 significantly augmented the number of FBGCs relative to the vector control (Figure 4, I and J). These results suggest that TRPV4 plays a direct role in macrophage fusion.

Figure 4.

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) plays a direct role in foreign body giant cell (FBGC) formation. Wild-type (WT) bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) treated with GSK2193874 (GSK219) or vehicle were stimulated with IL-4 + granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), as described in Figure 3, to induce macrophage fusion. A–C: Quantification of results. A: Number of foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) per high-power field. B: Percentage macrophage fusion. C: Nuclei per FBGC. A t-test was performed. D: To assess the effect of activation of TRPV4 by GSK1016790A (GSK101) on FBGC formation, WT BMDMs were treated with GSK101 or vehicle, and then stimulated with IL-4 + GM-CSF to induce FBGC formation. Giemsa-stained images shown are representative of five different fields per condition. E–H: Quantification of data from experiment shown in D. E: Number of FBGCs per high-power field. F: Percentage macrophage fusion. G: Nuclei per FBGC. H: Average size of FBGCs. A t-test was performed. I: Images are representative of five different fields per condition to assess the effect of TRPV4 gene-expressing constructs containing lentiviral particles [lenti-TRPV4–green fluorescent protein (GFP)] or control (cont.) GFP constructs containing lentiviral particles (lenti-GFP) expression in TRPV4 knockout (KO) BMDMs on FBGC formation. Arrows indicate the presence of FBGCs. J: Quantification of number of FBGCs per high-power field (HPF). Data are expressed as means ± SEM (B, C, E–H, and J). n = 3 independent experiments (B, C, E–H, and J). ∗P ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P ≤ 0.0001 (t-test). Scale bars: 100 μm (D); 50 μm (I).

Discussion

Biomaterials and medical devices are routinely used in millions of clinical procedures each year. However, the implantation of biomaterials/devices into soft tissue often leads to FBR, a fibroinflammatory condition, which is identified by excessive deposition of extracellular matrix, fusion of macrophages to form giant cells, fibrotic encapsulation, and stiffening of the adjacent tissue. The molecular mechanisms underlying the fibrotic/inflammatory responses are not well understood. The major findings of our current study are as follows: i) TRPV4 plays a role in biomaterial-induced FBR and giant cell formation in vivo; ii) TRPV4 deletion does not affect basal macrophage maturation in vivo; iii) TRPV4 deficiency results in impaired macrophage fusion in vitro; iv) TRPV4 is needed on only one fusion partner to form a giant cell; and v) TRPV4 plays a direct role in macrophage fusion. Taken together, our results suggest a potential role for TRPV4 in FBR. However, the mechanism by which TRPV4 affects FBR is unclear. TRPV4 is widely expressed in numerous tissues and cell types, including fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and macrophages, and is activated by both biochemical and mechanical stimuli.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Given the presence of several TRP family members, it is intriguing that mice deficient only in TRPV4 show modified pathophysiological conditions.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Recently, it was discovered that TRPV4 is required for transforming growth factor-β1/matrix stiffness–induced myofibroblast differentiation and pulmonary and skin fibrosis development in mice.17, 28 It has also been shown through studies by our group and others that numerous macrophage and fibroblast functions, including phagocytosis, adhesion, differentiation, and motility, are sensitive to changes in matrix stiffness and TRPV4 activity.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 28 In the current study, TRPV4 deficiency resulted in attenuated collagen deposition, a hallmark of fibrosis, and in diminished macrophage/FBGC accumulation. These results raise intriguing questions regarding the role of biomaterial and/or tissue stiffness in TRPV4-dependent FBR that warrant further study. Furthermore, although macrophages are recognized as the driver in FBR, other cell types, including fibroblasts, also play a critical role. For example, both macrophages/FBGCs and recruited fibroblasts/myofibroblasts deposit collagen fibers around the implanted material to form granulation tissue. Therefore, cell type–specific approaches will be required to address the role of TRPV4 in a specific cell type in FBR.

The functional significance of FBGCs, as well as the underlying mechanism of their generation, remains incompletely understood. Although TRPV4 has been implicated in numerous macrophage functions, its association in FBGC formation has not been reported previously. Blocking of TRPV4 activity (by genetic deficiency or pharmacologic antagonism by an antagonist) significantly diminished IL-4 + GM-CSF–induced FBGC formation. These data showed that FBGC formation was sensitive to TRPV4 channel activity. More importantly, re-expression of TRPV4 in TRPV4-null BMDMs resulted in a gain of the ability of these cells to undergo IL-4 + GM-CSF–induced FBGC formation. Thus, results from our gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies suggested that TRPV4 plays a direct role in FBGC formation. We also identified a requirement for TRPV4 expression by at least one of the fusing partners. Given the recognized role of cytoskeletal remodeling and activation of Rac1 in FBGC formation, we propose that during macrophage fusion, surface TRPV4 on one fusion partner promotes cytoskeleton rearrangement via activation of small GTPases to facilitate fusion with the other partner. Support for this hypothesis can be found in our previously published data showing that TRPV4 plays a role in F-actin generation and Rho activation in cytokine-stimulated fibroblasts.17

The next major question is to determine the signaling mechanism through which TRPV4 regulates FBGC formation. We postulate that TRPV4-induced activation of small GTPases and consequent reorganization of actomyosin structure via Ca2+ influx modulate FBGC formation. However, a plausible alternative is that activation of TRPV4 activates small GTPases through multiple pathways, including activation of Src family kinases, and transactivation of scavenger receptors. Further studies will be necessary to address these possibilities. Masuyama et al27 showed that TRPV4 was required for terminal differentiation and activity of osteoclasts, which are also multinucleated giant cells. Because TRPV4 channels have multiple physiological functions, including regulating osteoclast differentiation, direct targeting of TRPV4 in the treatment of FBR may be undesirable. Molecular strategies focused on downstream signaling molecules that target the FBR-promoting activity of TRPV4 without disrupting its beneficial functions may have greater therapeutic value.

Under certain stimulatory conditions, monocytes/macrophages are able to fuse to generate various types of multinucleated giant cells, such as Langhans giant cells, FBGCs, or osteoclasts. Results of in vitro experiments have shown that Langhans giant cell formation and FBGC formation are initiated by different sets of cytokines, interferon-γ versus IL-4 + GM-CSF, whereas osteoclast formation is the result of the action of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand + M-CSF. Giant cells are identified on the basis of the arrangement of nuclei within each giant cell and the appearance of the cytosol: in Langhans giant cells, nuclei are arranged at one pole; in FBGC, nuclei are randomly scattered; in osteoclasts, nuclei are scattered and accompanied by foamy cytosol. It has been reported that IL-4 stimulates the osteoclast inhibitor osteoprotegerin and reduces osteoclast formation from monocytes.34, 35, 36 GM-CSF is known to suppress osteoclast formation, while accelerating monocyte differentiation to macrophages during FBGC generation.34, 35, 36 In our study, we used a combination of IL-4 and GM-CSF to differentiate BMDMs to FBGCs, which we identified on the basis of a randomly scattered arrangement of nuclei. However, the possibility that Langhans giant cells and osteoclasts are present along with FBGCs in our in vivo models cannot be ruled out.

In summary, we show that TRPV4 is a novel mechanosensitive receptor/channel for biomaterial-induced FBR. The identification of factors regulating FBR may help to delineate mechanisms by which TRPV4 mediates the FBR to biomaterials and may help to identify therapeutic approaches based on targeting TRPV4 or its downstream mediators. Because receptors belonging to the TRPV family are responsible for sensing pain and heat, and are involved in hearing and balance, numerous pharmacologic inhibitors are currently under development, or in phase 1 trials,37 which would support a rapid translation of our results toward the amelioration of the FBR in patients.

Acknowledgments

S.O.R., R.G., and R.K.A. conceived the study, designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; D.B. and X.Z. assisted with experiments and analysis of data; all authors reviewed the results and approved the final content of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grant 1R01EB024556-01 (S.O.R.) and National Science Foundation grant CMMI-1662776 (S.O.R.).

Disclosures: None declared.

References

- 1.Ratner B.D. A pore way to heal and regenerate: 21st century thinking on biocompatibility. Regen Biomater. 2016;3:107–110. doi: 10.1093/rb/rbw006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Major M.R., Wong V.W., Nelson E.R., Longaker M.T., Gurtner G.C. The foreign body response: at the interface of surgery and bioengineering. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:1489–1498. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velnar T., Bunc G., Klobucar R., Gradisnik L. Biomaterials and host versus graft response: a short review. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2016;16:82–90. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2016.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson J.M., Rodriguez A., Chang D.T. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore L.B., Kyriakides T.R. Molecular characterization of macrophage-biomaterial interactions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;865:109–122. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18603-0_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browne S., Pandit A. Biomaterial-mediated modification of the local inflammatory environment. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2015;3:67. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown B.N., Ratner B.D., Goodman S.B., Amar S., Badylak S.F. Macrophage polarization: an opportunity for improved outcomes in biomaterials and regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3792–3802. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goswami R., Merth M., Sharma S., Alharbi M.O., Aranda-Espinoza H., Zhu X., Rahaman S.O. TRPV4 calcium-permeable channel is a novel regulator of oxidized LDL-induced macrophage foam cell formation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;110:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fereol S., Fodil R., Labat B., Galiacy S., Laurent V.M., Louis B., Isabey D., Planus E. Sensitivity of alveolar macrophages to substrate mechanical and adhesive properties. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2006;63:321–340. doi: 10.1002/cm.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blakney A.K., Swartzlander M.D., Bryant S.J. The effects of substrate stiffness on the in vitro activation of macrophages and in vivo host response to poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012;100:1375–1386. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Previtera M.L., Sengupta A. Substrate stiffness regulates proinflammatory mediator production through TLR4 activity in macrophages. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adlerz K.M., Aranda-Espinoza H., Hayenga H.N. Substrate elasticity regulates the behavior of human monocyte-derived macrophages. Eur Biophys J. 2016;45:301–309. doi: 10.1007/s00249-015-1096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheraga R.G., Abraham S., Niese K.A., Southern B.D., Grove L.M., Hite R.D., McDonald C., Hamilton T.A., Olman M.A. TRPV4 mechanosensitive ion channel regulates lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophage phagocytosis. J Immunol. 2016;196:428–436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Elias A., Mrkonjić S., Jung C., Pardo-Pastor C., Vicente R., Valverde M.A. The TRPV4 channel. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;222:293–319. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-54215-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everaerts W.1, Nilius B., Owsianik G. The vanilloid transient receptor potential channel TRPV4: from structure to disease. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2010;103:2–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liedtke W. Molecular mechanisms of TRPV4-mediated neural signaling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1144:42–52. doi: 10.1196/annals.1418.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahaman S.O., Grove L.M., Paruchuri S., Southern B.D., Abraham S., Niese K.A., Scheraga R.G., Ghosh S., Thodeti C.K., Zhang D.X., Moran M.M., Schilling W.P., Tschumperlin D.J., Olman M.A. TRPV4 mediates myofibroblast differentiation and pulmonary fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:5225–5238. doi: 10.1172/JCI75331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews B.D., Thodeti C.K., Tytell J.D., Mammoto A., Overby D.R., Ingber D.E. Ultra-rapid activation of TRPV4 ion channels by mechanical forces applied to cell surface beta1 integrins. Integr Biol (Camb) 2010;2:435–442. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00034e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thodeti C.K., Matthews B., Ravi A., Mammoto A., Ghosh K., Bracha A.L., Ingber D.E. TRPV4 channels mediate cyclic strain-induced endothelial cell reorientation through integrin-to-integrin signaling. Circ Res. 2009;104:1123–1130. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liedtke W., Tobin D.M., Bargmann C.I., Friedman J.M. Mammalian TRPV4 (VR-OAC) directs behavioral responses to osmotic and mechanical stimuli in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100 Suppl:14531–14536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235619100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adapala R.K., Thoppil R.J., Luther D.J., Paruchuri S., Meszaros J.G., Chilian W.M., Thodeti C.K. TRPV4 channels mediate cardiac fibroblast differentiation by integrating mechanical and soluble signals. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;54:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma S., Goswami R., Merth M., Cohen J., Lei K.Y., Zhang D.X., Rahaman S.O. TRPV4 ion channel is a novel regulator of dermal myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2017;312:C562–C572. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00187.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Conor C.J., Leddy H.A., Benefield H.C., Liedtke W.B., Guilak F. TRPV4-mediated mechanotransduction regulates the metabolic response of chondrocytes to dynamic loading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1316–1321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319569111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorneloe K.S., Cheung M., Bao W., Alsaid H., Lenhard S., Jian M.Y. An orally active TRPV4 channel blocker prevents and resolves pulmonary edema induced by heart failure. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:159ra148. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamanaka K., Jian M.Y., Weber D.S., Alvarez D.F., Townsley M.I., Al-Mehdi A.B., King J.A., Liedtke W., Parker J.C. TRPV4 initiates the acute calcium-dependent permeability increase during ventilator-induced lung injury in isolated mouse lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L923–L932. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00221.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Everaerts W., Zhen X., Ghosh D., Vriens J., Gevaert T., Gilbert J.P., Hayward N.J., McNamara C.R., Xue F., Moran M.M., Strassmaier T., Uykal E., Owsianik G., Vennekens R., De Ridder D., Nilius B., Fanger C.M., Voets T. Inhibition of the cation channel TRPV4 improves bladder function in mice and rats with cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19084–19089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005333107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masuyama R., Vriens J., Voets T., Karashima Y., Owsianik G., Vennekens R., Lieben L., Torrekens S., Moermans K., Vanden Bosch A., Bouillon R., Nilius B., Carmeliet G. TRPV4-mediated calcium influx regulates terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Cell Metab. 2008;8:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goswami R., Cohen J., Sharma S., Zhang D.X., Lafyatis R., Bhawan J., Rahaman S.O. TRPV4 ion channel is associated with scleroderma. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;137:962–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki M., Mizuno A., Kodaira K., Imai M. Impaired pressure sensation in mice lacking TRPV4. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22664–22668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahaman S.O., Lennon D.J., Febbraio M., Podrez E.A., Hazen S.L., Silverstein R.L. A CD36-dependent signaling cascade is necessary for macrophage foam cell formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyriakides T.R., Foster M.J., Keeney G.E., Tsai A., Giachelli C.M., Clark-Lewis I., Rollins B.J., Bornstein P. The CC chemokine ligand, CCL2/MCP1, participates in macrophage fusion and foreign body giant cell formation. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:2157–2166. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63265-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore L.B., Sawyer A.J., Charokopos A., Skokos E.A., Kyriakides T.R. Loss of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 alters macrophage polarization and reduces NFκB activation in the foreign body response. Acta Biomater. 2015;11:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jay S.M., Skokos E.A., Zeng J., Knox K., Kyriakides T.R. Macrophage fusion leading to foreign body giant cell formation persists under phagocytic stimulation by microspheres in vitro and in vivo in mouse models. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;93:189–199. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNally A.K., Anderson J.M. Interleukin-4 induces foreign body giant cells from human monocytes/macrophages. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1487–1499. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim M.S., Day C.J., Morrison N.A. MCP-1 is induced by receptor activator of nuclear factor-{kappa}B ligand, promotes human osteoclast fusion, and rescues granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor suppression of osteoclast formation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16163–16169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein N.C., Kreutzmann C., Zimmermann S.P., Niebergall U., Hellmeyer L., Goettsch C., Schoppet M., Hofbauer L.C. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 stimulate the osteoclast inhibitor osteoprotegerin by human endothelial cells through the STAT6 pathway. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:750–758. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moran M.M., McAlexander M.A., Bíró T., Szallasi A. Transient receptor potential channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:601–620. doi: 10.1038/nrd3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]