Abstract

Background

This study aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of extended depth of focus (EDOF) intraocular lenes (IOLs) in cataract surgery.

Methods

All comparative clinical trials that involved bilaterally implanting EDOF IOLs in patients with cataract were retrieved from the literature database. We used random effects models to pool weighted mean differences (WMD) and risk ratio (RR) for continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively.

Results

Nine studies with a total of 1336 eyes were identified. The subgroup analysis was conducted according to the type of IOLs used in the control group. Compared with monofocal IOLs, EDOF IOLs produced better uncorrected intermediate visual acuity (WMD: -0.17, 95% CI: − 0.26 to − 0.08, P = 0.0001) and uncorrected near visual acuity (WMD: -0.17, 95% CI: − 0.21 to − 0.12, P < 0.00001). EDOF IOLs resulted in reduced contrast sensitivity, more frequent halos, however, higher spectacle independence (RR: 2.81, 95% CI: 1.06 to 7.46, P = 0.04) than monofocal IOLs. Compared with trifocal IOLs, EDOF IOLs produced worse near visual acuity (MD: 0.10, 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.13, P < 0.0001). EDOF IOLs performed better than trifocal IOls in contrast sensitivity, and there were no significant difference in halos and spectacle independence. Serious postoperative complications were rare, with no adverse events were reported in most studies.

Conclusions

Increasing the risk of contrast reduction and more frequent halos, EDOF IOLs provided better intermediate and near VAs than monofocal IOLs. At the expense of near vision, patients receiving EDOF IOLs have better contrast sensitivity than those receiving trifocal IOLs. Halo incidence and spectacle independence of EDOF IOLs were similar to those of trifocal IOLs.

Keywords: Extended depth of focus, Trifocal, Monofocal, Intraocular lens, Cataract, Visual function, Meta-analysis

Background

Monofocal intraocular lenses (IOLs) are the most commonly implanted IOLs in cataract surgery [1]. With a single focal point, monofocal IOLs are effective in restoring satisfactory distance vision; however, most patients require spectacle correction for intermediate and near vision, even after surgery [1, 2]. Thus, multifocal IOLs were designed to meet the increasing demand from patients for spectacle independence [3]. For providing far, intermediate and near vision simultaneously, multifocal IOLs possess two or more independent focal points, which result in contrast reduction and increased photic phenomena, thus reducing visual quality [4].

More recently, a new-concept IOL was introduced based on extended depth of focus (EDOF) technology [5]. The basic principle behind EDOF IOLs is to create a single elongated focal point to enhance the depth of focus or range of vision [6]. A proprietary diffractive echelette design is used in EDOF IOLs and forms a step structure. The height, spacing, and profile of the echelettes are optimized to achieve constructive interference of light from different lens zones, thus producing a novel light diffraction pattern. In addition, proprietary achromatic technology and negative spherical aberration correction improve the image quality [7]. With technological advancement, EDOF IOLs showed good visual outcomes with less contrast reduction and fewer photic phenomena commonly associated with multifocal IOLs [4, 8]. However, according to some studies, EDOF lenses worked less efficiently for near vision than did trifocal IOLs [9, 10]. Currently, several types of EDOF IOLs are commercially available, including the Tecnis Symfony (Johnson and Johnson Vision), Mini WELL (Sifi Medtech), IC-8 (AcuFocus Inc) and Wichterle Intraocular Lens-Continuous Focus (Medicem). Until 2018, the Tecnis Symfony was the only United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved EDOF lens [6].

Although many studies have been conducted to characterize the efficacy and safety of EDOF IOLs, the unique features, such as visual acuity, vision quality and complications of EDOF IOLs is less clear-cut. Thus, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized controlled studies (NRCSs) to compare the clinical performance of EDOF IOLs with that of monofocal and trifocal IOLs. Finally, our study used only Tecnis Symfony IOL as the representative of EDOF IOLs due the lack of studies on other EDOF lenses.

Methods

Search strategy

The PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov and Cochrane Library databases (most recently updated in 2019 January) were searched using the keywords “extended depth of focus intraocular lens”, “extended range of vision intraocular lens” and “cataract surgery”. No language limitations were applied in the search strategy. In addition, the references of identified articles and reviews were checked and matching publications were included. Two reviewers (J. L. and Y. D.) independently conducted searches and scanned the abstracts, followed by full-text articles to determine whether the articles met the eligibility criteria. A third reviewer (Y. W.) was consulted when disagreement existed between J. L. and Y. D.

Eligibility criteria

We included all clinical controlled studies (randomized or nonrandomized, from 2000 to 2019 January) comparing clinical outcomes of EDOF IOLs with those of control IOLs in patients undergoing cataract surgery. However, studies involving patients with previous refractive surgery, irregular or > 1.0 diopter (D) corneal astigmatism and coexisting pathology, such as amblyopia, keratoconus, corneal endothelial dystrophy, chronic or recurrent uveitis, acute ocular disease or external/internal infection, diabetes mellitus with retinal changes, glaucoma and choroidal hemorrhage were excluded. We also excluded studies with double implantation in the same eye, no bilateral implantation, double reporting, in vitro experiments and no aggregated results.

Qualitative assessment and data extraction

The Jadad [11] and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [12] were used to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and NRCSs, respectively. The maximum NOS score is nine points, and a score over six points indicates good quality. Two reviewers (J. L. and Y. D.) independently extracted the characteristic data of included studies using a standard form; we tried to contact the author for sufficient information and original data when necessary. Discrepancies between two reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (Y. W.).

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes included binocular uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA), uncorrected intermediate visual acuity (UIVA), uncorrected near visual acuity (UNVA), defocus curves and contrast sensitivity. Visual acuity was evaluated using the high-contrast Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study chart in logMAR units under photopic conditions. Binocular defocus curves were done with best distance correction. Different levels of defocus were introduced in 0.50 D steps from + 1.00 to − 4.00 D. Contrast sensitivity under photopic and scotopic conditions for 1.5, 3.0, 6.0, 12.0, and 18.0 cycles per degree. The contrast sensitivity data was difficult to pool because of the considerable variety of the measurement methods. Thus, contrast sensitivity was instead reported descriptively. Halos, spectacle independence and postoperative complications were defined as the secondary outcomes. Spectacle independence was obtained from self-reported questionnaires and defined as the proportion of subjects who reported wearing glasses or contacts “none of the time” or “a little of the time” for overall vision.

Statistical analysis

We used RevMan software (version 5.3, Cochrane Collaboration) to analyze the data. The weighted mean difference (WMD) and risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively. A P-value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. Forest plots were used to present the results. In forest plots, only subtotals were analyzed because of the evident difference in design principles between monofocal and trifocal IOLs in control groups. Green boxes indicate the mean value, and the size of boxes indicates the weighting given to that estimate. The 95% CI for the estimate is shown as a horizontal line. The diamond represents the mean effect size. The center of the diamond represents the pooled point estimate, and the horizontal tips show the CI. We chose the random effects model for all data analyses because studies differed in trial design, patient ages, implanted IOLs, and the longest follow-up time. For multiarm studies, we combined groups to create a single pairwise comparison as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [13]. To verify the stability of the results, we performed sensitivity analysis by individually omitting the included studies. Publication bias was measured visually using funnel plots.

Heterogeneity management

Statistical heterogeneity was tested by I2 tests [14]. Findings were considered statistically significant if I2 > 50%. Under the assumption that the type of IOLs would explain a portion of heterogeneity, subgroups were defined as monofocal IOLs and trifocal IOLs in control groups.

Results

Result of the search

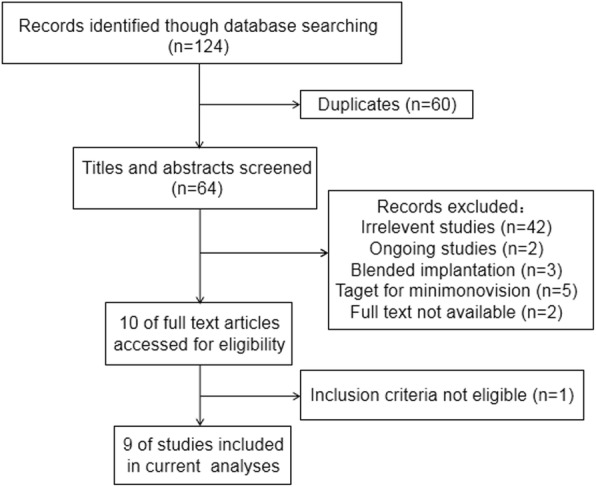

The electronic searches identified a total of 124 records. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the included and excluded studies. Two conference abstracts were excluded because the full text was unavailable [15, 16]. We tried to contact the author but did not receive a reply. Of 10 studies potentially relevant for this meta-analysis, one study enrolling patients with preexisting corneal astigmatism of 1.00 D or worse was excluded [17]. Ultimately, 9 studies were included in our quantitative analysis [9, 10, 18–24].

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing the study selection process

Study characteristics and quality

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and quality of the 9 studies that met all inclusion criteria [9, 10, 18–24]. Of the 9 selected studies, 3 were RCTs and 6 were NRCSs with a total of 1336 eyes. The studies were performed in various countries, and all studies were published between 2016 and 2018. The RCT sponsored by Abbott Medical Optics (AMO) company, leaded to the U.S. FDA approval of Tecnis Symfony IOL in 2016 [24]. Tecnis Symfony ZXR00 was used in the EDOF IOL group, while monofocal IOLs (Tecnis ZCB00 and AcrySof SN60WF) and trifocal IOLs (PanOptix, FineVison and Lisa tri 839MP) were used in the control groups. The follow-up period ranged from 3 to 29 months. The Jadad method was used to assess the methodological quality of RCTs in 3 respects: randomization, blindness and dropouts. Two of three RCTs were scored higher than 3 points. All six NRCSs were of relatively low risk of bias, scoring higher than 6 points on the NOS.

Table 1.

Characteristics and quality of included studies

| Studya, year | Location | Design | IOL | No. of patients/eyes | Longest follow up (month) | Jadad | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cochener, 2018 [9] | France | RCT |

Symfony PanOptix FineVison |

20/40 20/40 20/40 |

6 |

Randomization 1 Blindness 1 Dropouts 1 |

– |

| Mencucci, 2018 [10] | Italy | NRCS |

Symfony PanOptix Lisa tri 839MP |

20/40 20/40 20/40 |

3 | – | Selection 3 Comparability 2 Outcome 2 |

| AMO, 2017 [24] | United States | RCT |

Symfony ZCB00 |

148/296 151/302 |

6 |

Randomization 1 Blindness 2 Dropouts 1 |

– |

| Escandón-García, 2018 [18] | Portugal | NRCS |

Symfony PanOptix FineVison |

15/30 7/14 23/46 |

3 | – | Selection 3 Comparability 1 Outcome 2 |

| Monaco, 2017 [19] | Italy | RCT |

Symfony PanOptix SN60WF |

20/40 20/40 20/40 |

4 |

Randomization 2 Blindness 1 Dropouts 1 |

– |

| Pedrotti, 2016 [20] | Italy | NRCS |

Symfony ZCB00 |

25/50 15/30 |

3 | – | Selection 3 Comparability 2 Outcome 3 |

| Pilger, 2018 [21] | Germany | NRCS |

Symfony ZCB00 |

15/30 15/30 |

3 | – | Selection 3 Comparability 2 Outcome 3 |

| Ruiz-Mesa, 2017 [22] | Spain | NRCS |

Symfony FineVison |

20/40 20/40 |

12 | – | Selection 3 Comparability 2 Outcome 2 |

| Ruiz-Mesa, 2018 [23] | Spain | NRCS |

Symfony PanOptix |

14/28 20/40 |

29 | – | Selection 2 Comparability 2 Outcome 2 |

AMO Abbott Medical Optics, IOL intraocular lens, RCT randomized controlled trial, NRCS non-randomized controlled study

aFirst author or sponsor

Primary outcomes

Binocular uncorrected visual acuity

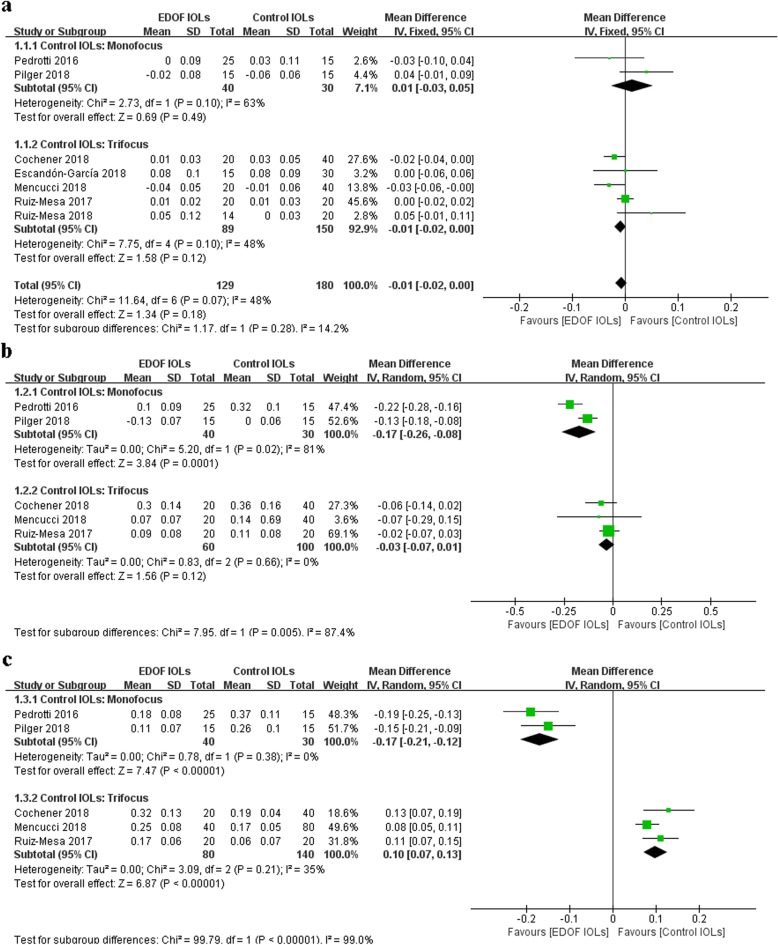

Seven [9, 10, 18, 20–23], five [9, 10, 20–22] and five [9, 10, 20–22] studies reported binocular UDVA, UIVA and UNVA, respectively (Fig. 2). One study did not report the standard deviation (SD) or other data to calculate the SD and thus was excluded from the analysis [24]. We tried to contact the author but did not receive a reply. The subgroup analysis was conducted according to the type of IOLs used in the control group. Compared with monofocal IOLs, EDOF IOLs provided comparable UDVA (WMD: 0.01, 95% CI: − 0.06 to 0.08, P = 0.81), better UIVA (WMD: -0.17, 95% CI: − 0.26 to − 0.08, P = 0.0001) and better UNVA (WMD: -0.17, 95% CI: − 0.21 to − 0.12, P < 0.00001). Compared with trifocal IOLs, EDOF IOLs showed no significant differences in UDVA (WMD: -0.01, 95% CI: − 0.03 to 0.01, P = 0.34) or UIVA (WMD: -0.03, 95% CI: − 0.07 to 0.01, P = 0.12) and performed worse in UNVA (WMD: 0.10, 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.13, P < 0.0001). In sensitivity analysis, no single study significantly changed the pooled estimate, indicating that the results were stable.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of binocular uncorrected visual acuity. a UDVA. b UIVA. c UNVA

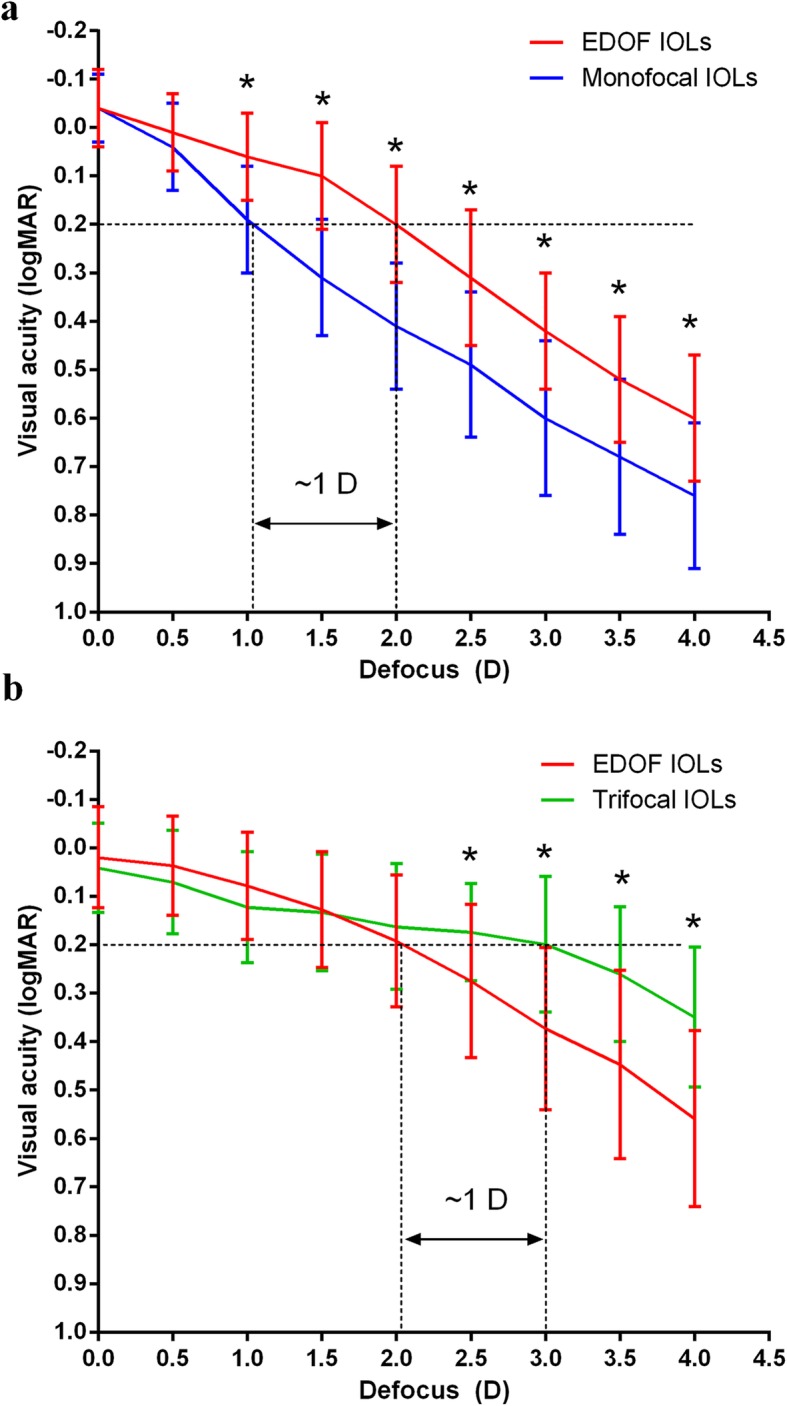

Defocus curves

Six studies [18–20, 22–24] reported binocular distance-corrected defocus curves. The binocular defocus curves based on 3 trails of 215 subjects for EDOF and monofocal IOLs and 4 trails of 159 subjects for EDOF and trifocal IOLs are shown in Fig. 3. Monofocal, EDOF and trifocal IOLs sustained 0.2 logMAR or better mean VA through 1.0 D, 2.0 D and 3.0 D, respectively. VA was significantly better with EDOF IOLs than with monofocal IOLs in the defocus levels from − 1.0 to − 4.0 D. VA was significantly better in trifocal IOL group than in EDOF IOL group from − 2.5 to − 4.0 D (Table 2). The sensitivity analysis showed that no single study significantly changed the pooled estimate, indicating the results of defocus curves were stable.

Fig. 3.

Defocus curves. a EDOF and monofocal IOLs. b EDOF and trifocal IOLs

Table 2.

Results of Meta-analysis for Defocus Curve

| Defocus levels | MD [95% CI] | P value | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | P heterogeneity | |||

| EDOF vs. Monofocal IOLs | ||||

| -0.01 | −0.00 (− 0.10, 0.08) | 0.81 | 89 | 0.0001 |

| −0.50 | −0.04 (− 0.09, 0.00) | 0.07 | 25 | 0.26 |

| −1.00 | −0.16 (− 0.21, − 0.12) | < 0.00001 | 0 | 0.65 |

| − 1.50 | − 0.22 (− 0.31, − 0.13) | < 0.00001 | 63 | 0.07 |

| −2.00 | − 0.24 (− 0.29, − 0.19) | < 0.00001 | 8 | 0.34 |

| − 2.50 | − 0.22 (− 0.27, − 0.16) | < 0.00001 | 0 | 0.45 |

| − 3.00 | − 0.25 (− 0.31, − 0.18) | < 0.00001 | 37 | 0.20 |

| −3.50 | − 0.21 (− 0.26, − 0.16) | < 0.00001 | 0 | 0.94 |

| −4.00 | −0.21 (− 0.26, − 0.16) | < 0.00001 | 0 | 0.73 |

| EDOF vs. Trifocal IOLs | ||||

| 0.00 | −0.02 (− 0.07, 0.03) | 0.40 | 59 | 0.06 |

| −0.50 | −0.03 (− 0.08, 0.01) | 0.17 | 52 | 0.10 |

| −1.00 | −0.04 (− 0.10, 0.01) | 0.11 | 55 | 0.08 |

| −1.50 | −0.01 (− 0.08, 0.07) | 0.88 | 76 | 0.006 |

| −2.00 | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.07) | 0.19 | 0 | 0.96 |

| −2.50 | 0.10 (0.06, 0.15) | < 0.00001 | 0 | 0.79 |

| −3.00 | 0.17 (0.09, 0.26) | < 0.0001 | 65 | 0.04 |

| −3.50 | 0.19 (0.07, 0.30) | 0.002 | 68 | 0.04 |

| −4.00 | 0.21 (0.07, 0.35) | 0.003 | 79 | 0.008 |

IOL intraocular lens, MD mean difference, CI confidence interval, I2 extent of inconsistency

Contrast sensitivity

Seven studies [10, 18, 20–24] reported contrast sensitivity and the results are summarized in Table 3. The U.S. FDA clinical trial reported that the median contrast scores for the EDOF IOL group were reduced compared to the monofocal control group under both conditions and each spatial frequency [24]. Pilger et al. reported that EDOF IOLs performed worse than did monofocal IOLs under scotopic conditions [21]. Pedrotti et al. reported no significant difference in contrast sensitivity between EDOF and monofocal IOLs under both photopic and scotopic conditions [20]. Mencucci et al. reported that EDOF performed significantly better than trifocal IOLs under both photopic and scotopic conditions [10]. Escandón-García et al. reported that EDOF IOLs performed better than trifocal IOLs at a frequency of 1.5 cycles per degree under scotopic conditions [18]. Two studies reported no difference in contrast sensitivity between EDOF and trifocal IOLs [22, 23].

Table 3.

Summary of Contrast Sensitivity and Halos

| Studya, year | EDOF IOLs | Control IOLs | CS: Under photopic conditions | CS: Under scotopic conditions | Halos |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedrotti, 2016 [20] | Tecnis Symfony | Tecnis ZCB00 | NSD | NSD | NSD |

| AMO, 2017 [24] | Tecnis Symfony | Tecnis ZCB00 | Better in monofocal IOLs group | Better in monofocal IOLs group | More halos in EDOF IOLs group |

| Pilger, 2018 [21] | Tecnis Symfony | Tecnis ZCB00 | NR | Better in monofocal IOLs group | NSD |

| Cochener, 2018 [9] | Tecnis Symfony | PanOptix/ FineVison | NR | NR | NSD |

| Escandón-García, 2018 [18] | Tecnis Symfony | PanOptix/ FineVison | NSD | For 1.5 cpd, better in EDOF IOLs group | NR |

| Mencucci, 2018 [10] | Tecnis Symfony | PanOptix/AT LISA tri 839MP | Better in EDOF IOLs group | Better in EDOF IOLs group | NSD |

| Monaco, 2017 [19] | Tecnis Symfony | PanOptix/SN60WF | NR | NR |

EDOF verses trifocus: NSD; Both were worse than monofocal IOL |

| Ruiz-Mesa, 2017 [22] | Tecnis Symfony | FineVison | NSD | NSD | NSD |

| Ruiz-Mesa, 2018 [23] | Tecnis Symfony | PanOptix | NSD | NSD | NSD |

AMO Abbott Medical Optics, EDOF extended depth of focus, CS contrast sensitivity, IOLs intraocular lenses, cpd cycles per degree, NSD no significant difference, NR not report

aFirst author or sponsor

Secondary outcomes

Halos

Eight studies [9, 10, 19–24] used questionnaires and Halo software to record halos. Because these studies used different questionnaires and measurements, conducting quantitative analyses of halos was inappropriate. Instead, the results are descriptively summarized in Table 3. Two studies reported no significant difference in halos between EDOF and monofocal IOLs [20, 21]. The U.S. FDA clinical trial reported that EDOF IOLs resulted in more frequent halos than monofocal IOLs [24]. Monaco et al. reported that both EDOF and trifocal IOLs resulted in more frequent halos than did monofocal IOLs [19]. Five studies reported no difference in halos between EDOF and trifocal IOLs [9, 10, 19, 22, 23].

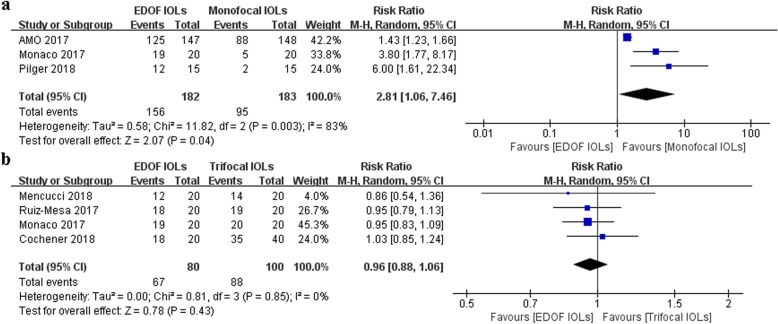

Spectacle Independence

Six studies [9, 10, 19, 21, 22, 24] reported spectacle independence. There was a significant difference in the overall effect that favored higher spectacle independence with EDOF IOLs than with monofocal IOLs (RR: 2.81, 95% CI: 1.06 to 7.46, P = 0.04) (Fig. 4a). The studies were characterized by high heterogeneity (I2 = 83%, P = 0.003). There was no significant difference between EDOF and trifocal IOLs in the overall effect (RR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.85 to 1.07, P = 0.45) (Fig. 4b). No significant heterogeneity was found (I2 = 0%, P = 0.61).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of spectacle independence. a EDOF and monofocal IOLs. b EDOF and trifocal IOLs

Postoperative complications

Two studies [22, 24] reported postoperative complications of EDOF IOLs. The complication reported in the U.S. FDA clinical trial included a rate of 1.35% for cystoid macular edema, 0.68% for pupillary capture, 0.68% for endophthalmitis and 0.68% for hypopyon 6 months postoperatively [24]. One study reported 0 and 5% of patients had posterior capsule opacification 12 months postoperatively in the EDOF IOL group and trifocal IOL group respectively [22].

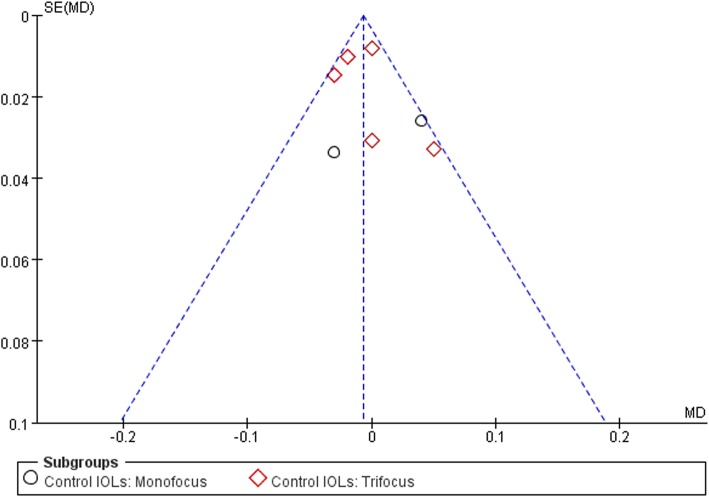

Publication Bias

The publication bias of the studies was determined by a funnel plot. The symmetrical funnel plot showed no significant publication bias in the publications (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot for publication bias test

Discussion

The present meta-analysis compared the clinical performance of EDOF IOLs with those of monofocal and trifocal IOLs. According to the results, compared with monofocal IOLs, EDOF IOLs have benefits for intermediate and near vision, but also increase the risk of contrast reduction and more frequent halos. Although EDOF IOLs worked less efficiently for near vision than did trifocal IOLs, they maintained better contrast sensitivity and no differences were found in halo incidence and spectacle independence.

All studies included in this meta-analysis involved bilateral implantation. Implantation of the same IOLs in both eyes avoids overestimating or underestimating the efficacy of the IOL caused by interference from the follow eye. Therefore, bilateral implantation is a more effective way to measure the effect of IOLs on quality of life [25].

Creating a single elongated focal point to enhance the range of vision, EDOF IOLs expectedly provided better uncorrected intermediate and near VA than that of monofocal IOLs [6]. However, EDOF IOLs performed worse on near vision than did trifocal IOLs that splits light into distant, intermediate and near focal points. So the near vision of EDOF IOLs is somewhere between that of monofocal and trifocal IOLs. EDOF IOLs and trifocal IOLs performed similarly on distance and intermediate visions. To reflect vision-related quality of life more directly, uncorrected VAs, instead of corrected VAs were main vision outcomes in our meta-analysis [26].

Binocular defocus curves also showed comparable distance and intermediate visions with EDOF and trifocal IOLs and better near vision with trifocal IOLs. Although EDOF IOLs improved the range of defocus with VAs of 0.2 logMAR or better by approximately 1 D than monofocal IOLs, trifocal IOLs had the longest range of defocus from 0 to − 3.0 D (VA above 0.2 logMAR). Therefore, EDOF IOLs had superior visual outcomes between 1 m and 25 cm than monofocal IOLs and inferior visual outcomes between 40 cm and 25 cm than trifocal IOLs. Based on the results of VAs and defocus curves, the EDOF IOL provides excellent distance and intermediate vision but mediocre near vision.

All monofocal IOLs involved in the current study were aspherical. Aspherical monofocal IOLs have been reported to provide higher contrast sensitivity than spherical IOLs and multifocal IOLs [27]. Although the Symfony EDOF IOL employed achromatic and aspheric technologies to maintain visual quality [6], it caused a reduction in contrast sensitivity compared to aspherical monofocal IOLs. With EDOF IOLs, there is a tradeoff between the clarity of near vision and contrast sensitivity. However, the present study found that the contrast sensitivity of EDOF IOLs was higher than that of trifocal IOLs, especially under scotopic conditions [10, 18]. In trifocal IOLs, the distribution of light to more than one focus results in contrast reduction postoperatively, one of the major limitations of multifocal IOLs [4].

Depending on the difference in individual habits and lifestyle in real contexts, spectacle independence is a subjective parameter. Although EDOF IOLs worked less efficiently for near vision than did trifocal IOLs, there was no difference between EDOF and trifocal IOLs in self-reported spectacle independence. In addition, there was no difference in halo incidence between the two groups. This may be explained by the fact that most patients are capable of adapting and tend to become more tolerant of photic phenomena several months postoperatively [28].

Serious postoperative complications were rare and most of studies did not routinely include complications in their outcome measures. One study reported that trifocal IOLs induced more posterior capsule opacification than EDOF IOLs 12 months postoperatively [22]. More studies are needed to prove the safety of EDOF IOLs.

To our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to compare the clinical performance of EDOF IOLs in cataract surgery with that of monofocal and trifocal IOLs, respectively. However, this meta-analysis has several limitations. First, between-study heterogeneity was substantial. The included studies varied in length of follow-up, types of IOLs in the control group, study location and measurement methods. We chose the random model for all data analyses and tried to explain the heterogeneity by subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. The results were stable in sensitivity analyses by individually omitting the included studies. Second, only 3 of the included studies were RCTs, and the remaining studies were NRCSs that had a potential selection bias. Third, publication bias was suspected due to the exclusion of unpublished studies and conference abstracts. Last, limited number of studies reported postoperative complications. More clinical trails that record postoperative adverse effects are needed to assess the safety of EDOF IOLs.

Conclusions

This systematic review revealed the unique features of EDOF IOLs when compared with other types of IOLs. Compared with monofocal IOLs, EDOF IOLs have benefits for intermediate and near vision but also increase the risk of contrast reduction and more frequent halos. Compared to trifocal IOLs, EDOF IOLs worked less efficiently for near vision; however, this limitation may be an acceptable compromise to patients, given the accompanying retained contrast sensitivity. In conclusion, EDOF IOLs are efficient at providing distance and intermediate visions and safe with rare serious postoperative complications. Nevertheless, more clinical trails with randomized and controlled study designs and adequate duration are needed to clarify the tradeoffs between EDOF IOLs and other presbyopia-correcting IOLs.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AMO

Abbott Medical Optics

- CI

Confidence interval

- D

Diopter

- EDOF

Extended depth of focus

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- IOLs

Intraocular lenses

- logMAR

Logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- NRCS

Nonrandomized controlled studies

- RCT

Randomized controlled trials

- RR

Risk ratio

- SD

Standard deviation

- UDVA

Uncorrected distance visual acuity

- UIVA

Uncorrected intermediate visual acuity

- UNVA

Uncorrected near visual acuity

- VA

Visual acuity

- WMD

Weighted mean differences

Authors’ contributions

JL and YW contributed to the conception of the work. JL and YD searched the literature and extracted the data. JL and YD wrote the manuscript. YW revised the manuscript and produced the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81670884 and 81873684).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.de Silva SR, Evans JR, Kirthi V, Ziaei M, Leyland M. Multifocal versus monofocal intraocular lenses after cataract extraction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD003169. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003169.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li S, Jie Y. Cataract surgery and lens implantation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2019;30:39–43. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salerno LC, Tiveron MC, Jr, Alio JL. Multifocal intraocular lenses: types, outcomes, complications and how to solve them. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2017;7:179–184. doi: 10.4103/tjo.tjo_19_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vries NE, Webers CA, Touwslager WR, Bauer NJ, de Brabander J, Berendschot TT, et al. Dissatisfaction after implantation of multifocal intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:859–865. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocha KM. Extended depth of focus IOLs: the next chapter in refractive technology? J Refract Surg. 2017;33:146–149. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20170217-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akella SS, Juthani VV. Extended depth of focus intraocular lenses for presbyopia. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018;29:318–322. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gatinel D, Loicq J. Clinically relevant optical properties of bifocal, trifocal, and extended depth of focus intraocular lenses. J Refract Surg. 2016;32:273–280. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20160121-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachdev GS, Ramamurthy S, Sharma U, Dandapani R. Visual outcomes of patients bilaterally implanted with the extended range of vision intraocular lens: a prospective study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:407–410. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_813_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochener B, Boutillier G, Lamard M, Auberger-Zagnoli C. A comparative evaluation of a new generation of diffractive trifocal and extended depth of focus intraocular lenses. J Refract Surg. 2018;34:507–514. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20180530-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mencucci R, Favuzza E, Caporossi O, Savastano A, Rizzo S. Comparative analysis of visual outcomes, reading skills, contrast sensitivity, and patient satisfaction with two models of trifocal diffractive intraocular lenses and an extended range of vision intraocular lens. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256:1913–1922. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-4052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from: http://www.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed 21 Jan 2016.

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attia M, Khoramnia R, Rabsilber T, Holzer MP, Auffarth GU. Comparison of the functional results of bifocal, trifocal and extended-depth of focus intraocular lenses. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;45(suppl 1):46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul R, Rayside M. Comparison of 3 Presbyopic correcting intraocular lenses. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;44(suppl 1):71. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedrotti E, Carones F, Aiello F, Mastropasqua R, Bruni E, Bonacci E, et al. Comparative analysis of visual outcomes with 4 intraocular lenses: Monofocal, multifocal, and extended range of vision. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escandon-Garcia S, Ribeiro FJ, McAlinden C, Queiros A, Gonzalez-Meijome JM. Through-focus vision performance and light disturbances of 3 new intraocular lenses for presbyopia correction. J Ophthalmol. 2018;2018:6165493. doi: 10.1155/2018/6165493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monaco G, Gari M, Di Censo F, Poscia A, Ruggi G, Scialdone A. Visual performance after bilateral implantation of 2 new presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses: trifocal versus extended range of vision. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43:737–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2017.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedrotti E, Bruni E, Bonacci E, Badalamenti R, Mastropasqua R, Marchini G. Comparative analysis of the clinical outcomes with a Monofocal and an extended range of vision intraocular Lens. J Refract Surg. 2016;32:436–442. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20160428-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pilger D, Homburg D, Brockmann T, Torun N, Bertelmann E, von Sonnleithner C. Clinical outcome and higher order aberrations after bilateral implantation of an extended depth of focus intraocular lens. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2018;28:425–432. doi: 10.1177/1120672118766809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz-Mesa R, Abengozar-Vela A, Aramburu A, Ruiz-Santos M. Comparison of visual outcomes after bilateral implantation of extended range of vision and trifocal intraocular lenses. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2017;27:460–465. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz-Mesa R, Abengozar-Vela A, Ruiz-Santos M. A comparative study of the visual outcomes between a new trifocal and an extended depth of focus intraocular lens. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2018;28:182–187. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5001029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ClinicalTrials.gov, Clinical investigation of a new intraocular lens. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02203721. Accessed 12 Jan 2019.

- 25.Leyland M, Zinicola E. Multifocal versus monofocal intraocular lenses in cataract surgery: a systematic review. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1789–1798. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00722-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel I, Munoz B, Burke AG, Kayongoya A, Mchiwa W, Schwarzwalder AW, et al. Impact of presbyopia on quality of life in a rural African setting. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng M, Liu Y, Liu X, Yuan Z, Luo L, Xia Y, et al. Aberration and contrast sensitivity comparison of aspherical and monofocal and multifocal intraocular lens eyes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;35:355–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2007.01452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sood P, Woodward MA. Patient acceptability of the Tecnis multifocal intraocular lens. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:403–410. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S11126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.