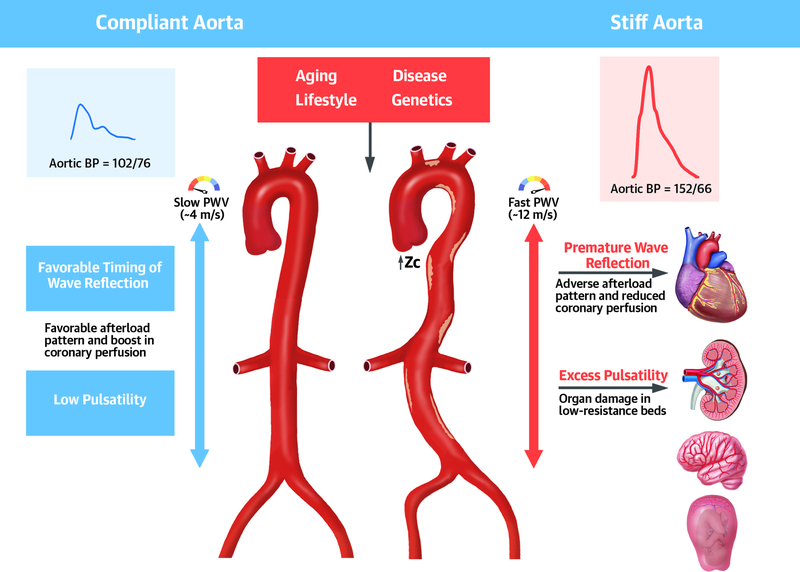

Central Illustration.

Role of large artery stiffness in health and disease. In young healthy adults, a compliant aorta (left): (a) effectively buffers excess pulsatilty due to the intermittent left ventricular ejection; (b) exhibits a slow pulse wave velocity (PWV), which allows pulse wave reflections to arrive to the heart during diastole, increasing diastolic coronary perfusion pressure but not systolic ventricular load. A number of factors (aging, lifestyle, etc.) increase aortic wall stiffness, which leads to several adverse hemodynamic consequences. Aortic stiffening leads to increased aortic root characteristic impedance (Zc) and forward wave amplitude on one hand, and premature arrival of wave reflections to the heart on the other. These hemodynamic changes result in adverse patterns of pulsatile load to the left ventricle in systole and a reduced coronary perfusion pressure in diastole, ultimately promoting myocardial remodeling, dysfunction, failure and a reduced perfusion reserve (even in the absence of epicardial coronary disease). This adverse hemodynamic pattern also results in excessive pulsatility in the aorta, which is transmitted preferentially to low-resistance vascular beds (such as the kidney, placenta and brain), because in these organs, microvascular pressure is more directly coupled with aortic artery pressure fluctuations. PWV=pulse wave velocity; Zc=characteristic impedance; BP=blood pressure.