Abstract.

The neglected tropical diseases Zika, Ebola, and Lassa fever (LF) have all been noted to cause some degree of hearing loss (HL). Hearing loss is a chronic disability that can lead to a variety of detrimental effects, including speech and language delays in children, decreased economic productivity in adults, and accelerated cognitive decline in older adults. The objective of this review is to summarize what is known regarding HL secondary to these viruses. Literature for this review was gathered using the PubMed database. Articles were excluded if there were no data of the respective viruses, postinfectious complications, or conditions related to survivorship. A total of 50 articles were included in this review. Fourteen articles discussing Zika virus and subsequent complications were included. Across these studies, 56 (21.2%) of 264 Zika-infected individuals were found to have HL. Twenty-one articles discussing Ebola virus and subsequent complications were included, with 190 (5.7%) of 3,350 Ebola survivors found to have HL. Fifteen additional articles discussing LF and subsequent complications were included. Of 926 individuals with LF, 79 (8.5%) were found to have HL. These results demonstrate a relationship between HL and infection. The true prevalence is likely underestimated, however, because of lack of standardization of reporting and measurement. Future studies of viral sequelae would benefit from including audiometric evaluation. This information is critical to understanding pathophysiology, preventing future cases of this disability, and improving quality of life after survival of infection.

INTRODUCTION

Tropical diseases have immense societal impact due in large part to their myriad long-term sequelae. Classically, these disabilities include physical impairments such as blindness, limb and physical deformities, an increased number of negative maternal and neonatal outcomes, and delayed physical or mental development.1,2 Furthermore, the association of these illnesses with poverty and the loss of productivity resulting from these disabilities lead to increased levels of stigma and social isolation, which contributes to the total burden of disease.3–6 The calculation and comparison of the number of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost because of neglected tropical diseases (56.6 million DALYs) to other more common diseases such as HIV/AIDS (84.5 million DALYs) and malaria (46.5 DALYs) illustrates the large impact of these diseases on the populations they affect.1,4,5 Hearing loss (HL) is an often neglected and understudied sequelae of these infections, which contributes to the number of DALYs lost. Hearing loss affects more than 1.3 billion people worldwide and is now the 4th leading cause of years lived with disability.7 The effects of HL are lifelong and span from speech and language delays in childhood to restricted employment opportunities in adults and accelerated cognitive decline in older adults.8–14 The global burden of HL is unequally distributed, with more than 80% of affected individuals living in low- and middle-income countries, the very places where access to hearing care is limited.

Viruses were first established as an etiology of HL in the 1950s and are suspected to contribute to 12.8–25% of sudden-onset HL cases.15–17 Zika, Ebola, and Lassa fever (LF) are all tropical diseases which have received little worldwide attention until recent epidemics, and each of these viruses has been reported to be associated with HL. By comparing the prevalence reported for these and other viruses, Zika, Ebola, and LF may be associated with HL prevalence, that is, up to 300× greater than that of more common and better understood viral etiologies.18–21 The true burden of HL secondary to Zika, Ebola, and LF is unknown, however, and may be underreported because of lack of proper measurement of this chronic disability. Despite the paucity of data, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes the potential public health impact of these associations and has requested a review of the existing literature on Zika, Ebola, and LF for the upcoming World Report on Hearing, to be released in 2020. The objective of this review is, therefore, to describe what is known regarding HL secondary to these three tropical diseases, identify gaps in knowledge, and propose areas of research to increase our understanding of pathophysiology and potentially lead to new treatment modalities for viral-mediated HL.

METHODS

This literature search and analysis was conducted from August 2018 through April 2019. All study designs, publication dates, and languages were considered. Literature was gathered from PubMed using key terms and Boolean operators. Key terms used included the following: Zika, Ebola, Lassa, Survivors, Sequelae, HL, Hearing Impairment, Deafness, Complications, Congenital, and Post-Ebola Syndrome. Abstracts and titles of all retrieved studies were reviewed for mention of secondary complications, and the full texts of relevant articles were obtained. Articles were excluded if there were no data or discussion of the respective viruses, postinfectious complications, or conditions related to survival but not directly caused by the virus itself. Data regarding demographics and HL were gathered and aggregated according to the respective cause of infection. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed as applicable in creation of this review.

RESULTS

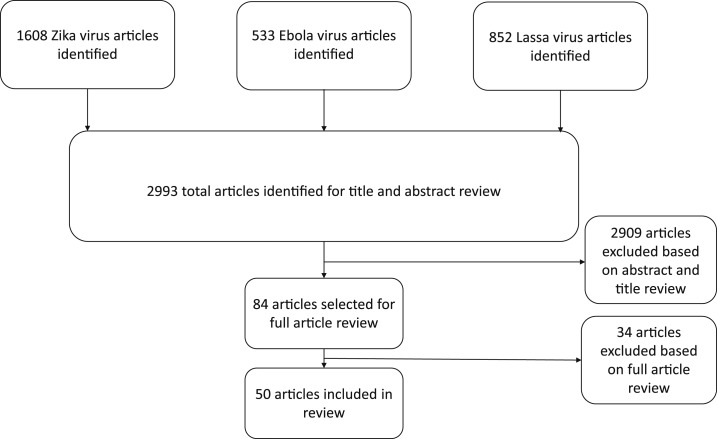

Two thousand nine hundred ninety-three total articles were identified by this methodology. Of these, 2,909 articles were excluded based on abstract and title review and 34 articles were excluded based on full article review. A total of 50 articles were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature search results.

Hearing loss and Zika.

Fourteen articles discussing Zika virus and subsequent complications in 347 individuals were included in this review (Table 1). Across studies, 56 (21.2%) of 264 individuals were found to have some degree of HL.18,22–34 Four of the fourteen articles described acquired HL in adults following Zika infection (Table 1). The HL in these cases varied from moderate to severe and was reported as both unilateral and bilateral, with most patients experiencing recovery to normal or previous thresholds.22–24,30 Ten articles presented complication data of congenital Zika syndrome related to HL (Table 1).18,22,25–29,33–35 The majority of these studies used standard HL screening methods for infants, including measurement of auditory brainstem response and otoacoustic emission, which assesses cochlear function.18,25–29,31,33,34 The proportion of infants with reported HL in these studies varied from 6% to 68%. One article presented in-depth testing of two individuals, one of whom had moderate unilateral HL and one with normal hearing thresholds. Importantly, the patient with HL was also found to have poor speech recognition scores in the same ear. These studies suggest the association of Zika virus not only with HL but also with auditory processing disorders such as auditory neuropathy. The wide range of HL prevalence found by this analysis indicates the need for further research on this disability.

Table 1.

Adult and congenital Zika hearing loss (HL) findings by year

| First author | Publication year | Study type | Sample size (n) | Age group | HL Screening Method | HL result (n, %) | Unilateral HL (n) | Bilateral HL (n) | Control group (n, % HL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tappe23 | 2014 | Case report | 1 | Adult | Self-report | 1 (100) | NR | NR | ND |

| M.E.R.G29 | 2015 | Cross-sectional | 23* | Neonatal | OAE | 2 (9) | NR | NR | ND |

| Leal18 | 2016 | Retrospective cohort | 70 | Pediatric | ABR to click and tone burst stimuli | 5 (6) | NR | NR | ND |

| Leal25 | 2016 | Case series | 2 | Neonatal | Transient OAE followed by ABR to click stimuli | 1 (50) | NR | NR | ND |

| Vinhaes24 | 2017 | Case series | 3 | Adult | Audiometry | 3 (100) | 1 | 2 | ND |

| Martins22 | 2017 | Case series | 2 | Adult | Audiometry | 1 (50) | 1 | 0 | ND |

| Satterfeldt27 | 2017 | Cross-sectional | 19 | Pediatric | Physician-reported HINE assessment | 13 (68) | NR | NR | ND |

| Santos28 | 2017 | Case series | 2 | Neonatal | Evoked OAE followed by ABR | 1 (50) | NR | NR | ND |

| Wheeler26 | 2018 | Cross-sectional | 47 | Pediatric | No response to voice or sound | 13 (28) | NR | NR | ND |

| Does not look for sound | 8 (17) | ||||||||

| No response to word “No” | 20 (43) | ||||||||

| de Laval30 | 2018 | Prospective cohort | 49 | Adult | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Ventura31 | 2018 | Case report | 1 | Neonatal | ABR to click stimuli | 1 (100) | 1 | 0 | ND |

| Franca32 | 2018 | Cross-sectional | 8 | Pediatric | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Vianna33 | 2019 | Prospective cohort | 26 | Pediatric | ABR | 2 (8) | NR | NR | 65 (3) |

| Calle-Giraldo34 | 2019 | Prospective cohort | 68 | Neonatal | ABR | 6 (9) | 3 | 3 | ND |

ABR = auditory brainstem response; ND = not done; NR = not reported; OAE = otoacoustic emission; HINE = Hammersmith infant neurological examination Adult, 18 years or greater; pediatric, 0–24 months; neonatal, anomalies detected at birth.

* Total sample size of 104, only 23 screened for HL.

Hearing loss and Ebola.

Twenty-one articles discussing Ebola virus and subsequent complications in 5,055 individuals were included in this review (Table 2). Of the 3,385 individuals studied, 223 (6.6%) were found to have some degree of HL using audiometric evaluation and survey instruments.19,36–55 Only one of 21 articles used audiometry to objectively measure HL. This study, by Rowe et al.,19 recruited convalescent Ebola survivors and household contacts following the conclusion of the 1995 Ebola outbreak in Kikwit, DRC. The study defined HL as an inability to hear at least 1 frequency between 0.5 and 4 kHz at 25 dB. The authors reported that 18 (64.3%) of 27 individuals developed HL after surviving Ebola infection, and 11 of these patients had developed HL within the first 6 months following discharge from Ebola treatment centers. At the end of the 21-month follow-up period, seven individuals (26%) were found to have persistent HL. The remainder of the articles that described HL as sequelae of Ebola relied on questionnaires or self-report of symptoms.36–46,50,52–54 The proportion of individuals reporting HL in these articles varied widely, from 0% to 22%. In these studies relying on self-report, HL typically arose late in the course of the disease and persisted throughout recovery. Self-reported timing of HL onset was broad, spanning from the initial hospital admission to as many as 350 days post discharge.36–40,42 Despite continued complaints of HL, the lone study to measure HL by audiometry demonstrated resolution in several individuals.19 Thus, it is possible that HL related to Ebola may resolve spontaneously. Data regarding Ebola-related HL is scarce, and more studies are required to elucidate the persistence of this disability.

Table 2.

Ebola hearing loss (HL) findings by hearing screening method by year

| First author | Publication year | Study type | Sample size (n) | Median age (years) | HL screening method | HL results (n, %) | Days to HL onset (median DPI) | Control group (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rowe19 | 1999 | Prospective cohort | 29 | 27 | Audiometry | 18 (64.3) | < 180 | 152 (NR) |

| Bwaka42 | 1999 | Retrospective cohort | 103 | 38 | Self-Reported | 13 (12.6) | NR | ND |

| Clark43 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 70 | 40 | Questionnaire | 13 (27) | NR | 223 (10) |

| Qureshi38 | 2015 | Cross-sectional | 105 | 38.9* | Questionnaire | 0 (0) | NR | ND |

| Mattia37 | 2016 | Cross-sectional | 277 | 29 | Self-report | 17 (6) | 14 | ND |

| Jacobs36 | 2016 | Case report | 1 | 39 | Self-report | 1 (100) | 11 | ND |

| Tiffany39 | 2016 | Prospective cohort | 166 | 24.7† | Self-reported | 5 (3) | 31–60 | ND |

| Nanyonga46 | 2016 | Cross-sectional | 81 | 29 | Questionnaire | NR | NR | ND |

| Fallah49 | 2016 | Retrospective cohort | 70 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Etard40 | 2017 | Cross-sectional | 802 | 28.4 | Self-reported | 19 (2.4) | 350 | ND |

| Shantha41 | 2017 | Cross-sectional | 96 | 38.6 | Self-reported | 10 (10.4) | NR | ND |

| Hereth-Hebert48 | 2017 | Prospective cohort | 341 | 26 | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Wilson45 | 2018 | Cross-sectional | 242 | 30 | Questionnaire | 4 (1.6) | NR | ND |

| Jagadesh44 | 2018 | Retrospective case control | 27 | NR | Questionnaire | 5 (18.5) | NR | 54 |

| Kelly47 | 2018 | Cross-sectional | 20 | 53.2* | NR | NR | NR | 187 (NR) |

| Wing50 | 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 137 | 25 | Self-report | 30 (22) | NR | ND |

| Overholt51 | 2018 | Prospective cohort | 299 | 31 | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Howlett52 | 2018 | Case series | 35 | 28 | Self-report | 3 (8.6%) | NR | ND |

| de St. Maurice53 | 2018 | Cross-sectional | 329 | 33† | Questionnaire | 19 (6) | NR | ND |

| Kelly55 | 2019 | Prospective cohort | 859 | 12–50+† | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| PREVAIL54 | 2019 | Prospective cohort | 966 | NR | Self-report | 66 (6.8%) | NR | 2,350 (2.2) |

DPI = days postinfection; ND = not done; NR = not reported.

* Age reported as mean age of sample.

† Only range of ages reported.

Hearing loss and LF.

Fifteen articles discussing LF and subsequent complications in 1,207 individuals were included in this review (Table 3).20,56–69 Of 15 articles, 11 presented HL data.20,56–65 Across studies, 53 (6.0%) of 898 individuals were found to have some degree of HL using audiometric evaluation and survey instruments.20,56–64 Thirty-eight (71.7%) affected individuals were found to have bilateral HL, and 15 (28.3%) individuals demonstrated unilateral HL. Audiometry was used to characterize HL in five of 11 studies.20,56–69 The mean pure-tone average (PTA) for all reported data was 66.5 dB, which is consistent with severe HL. This measurement was gathered from 139 (15.5%) of 898 individuals with an average age of 33.7 years. Several studies monitored progression of HL. Eleven of 22 individuals were found to have residual HL at 1 year, and one reported residual loss 4 years after the initial infection.20,57–59,62,63 At the end of the 1 year period, nine of these individuals were found to have severe HL, including three cases of bilateral HL and six cases of unilateral.20 Cummins and colleagues included three separate evaluations to characterize the HL secondary to LF infection.20 In the third evaluation, a case-control study of 32 individuals with HL in comparison with 32 individuals without, 26 (81.2%) of 32 individuals with HL were found to be seropositive for LF antibodies versus only six (18.7%) of those without HL. Interestingly, only 13 (50%) seropositive individuals with HL were aware that LF might be the cause of HL.20 These studies indicate that LF may be an underappreciated cause of HL in LF endemic areas. This analysis finds that the prevalence of LF-related HL ranges widely, from 0% to 81.25%. More robust studies are needed to determine the relationship between symptomatic disease, HL and seropositivity.

Table 3.

Lassa Fever HL Findings by year

| First author | Publication year | Study type | Sample size | Mean age (years) | HL screening method | HL results (n, %) | Average severity of HL* | Unilateral HL | Bilateral HL | Days to HL onset (median DPI) | Control group (n, % HL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White63 | 1972 | Case series | 23 | 26.6 | Self-report | 4 (17.4) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Mertens64 | 1973 | Cross-sectional | 10 | 20–56‡ | Self-report | 3 (30%) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Grundy57 | 1980 | Case report | 1 | 25 | Self-report | 1 (100) | NR | 1 | 0 | 14 | ND |

| McCormick60 | 1987 | Case–control | 430 | NR | NR | 12 (2.8) | NR | 3 | 9 | 10–15 | ND |

| Frame68 | 1987 | Cross-sectional | 33 | < 1† | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Hirabayashi69 | 1988 | Case report | 1 | 48 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Frame67 | 1989 | Retrospective | 246 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Cummins20 | 1990 | Prospective cohort | 49 | 30.2 | Audiometry | 14 (28.6) | Severe | 7 | 14 | 5-12 | ND |

| Cummins20 | 1990 | Case–control | 51 | 30.3 | Audiometry | 9 (17.6) | Moderate | 3 | 6 | NR | 45 (4) |

| Günther66 | 2001 | Case report | 1 | 56 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

| Macher61 | 2006 | Case series | 2 | 34.5 | Audiometry | 1 (50) | NR | 1 | 0 | NR | ND |

| Okokhere56 | 2009 | Case series | 2 | 31 | Audiometry | 2 (100) | Severe | 0 | 2 | 9 | ND |

| Ibekwe62 | 2011 | Prospective cohort | 37 | 35.3 | Audiometry | 5 (13.5) | Severe | 0 | 5 | NR | 37 (0) |

| Grahn59 | 2016 | Case report | 1 | 72 | Self-report | 1 (100) | NR | 0 | 1 | 22 | ND |

| Choi58 | 2018 | Case report | 1 | 46 | Self-report | 1 (100) | NR | 0 | 1 | 5 | ND |

| Okokhere65 | 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 291 | 35 | NR | 0 (0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ND |

DPI = days postinfection; HL = hearing loss; ND = not done; NR = not reported.

* Severity determined based on WHO standards.

† Ordinal data presented were used to calculate median age.

‡ Only range of ages reported.

DISCUSSION

The major lifelong sequelae of neglected tropical diseases are secondary disabilities following infection. HL is an understudied morbidity following these viral tropical disease pathogens. This review examines the association between HL and Zika, Ebola, and LF viruses, summarizing what is known regarding this complication. Results of this analysis demonstrate the range of HL prevalence associated with each of these viruses. The major limitation is the small amount of data that exist to fully characterize this disability and the lack of studies that follow any standard protocol of measurement or reporting, which likely underestimates the true prevalence and undermines data quality. Furthermore, few studies attempt repeat screening to detect progression or late-onset HL. Social stigma and psychiatric complaints are reported complications of both HL and these tropical diseases.8,9,70–74 However, no studies have examined the relationship between these complications.

Important similarities and differences were observed in HL associated with the three viruses. Zika virus, a well-described cause of birth defects, may also lead to various levels of HL in both acquired and congenital cases. Interestingly, in-depth audiology testing in the acquired cases of Zika-related HL suggested the presence of a sound processing disorder called auditory neuropathy.75,76 The association of Zika with this type of retrocochlear HL has important public health implications because auditory neuropathy is not identified with typical methods of hearing screening. Hearing loss in congenital Zika cases was commonly reported in children older than 1 year, suggesting that Zika may lead to delayed onset of HL and emphasizing the need for recurring screening beyond the newborn period.21 The most well-supported hypothesis of the mechanism for Zika-related HL is direct viral invasion of neurons in the auditory pathway.77–79 The virus has been shown to have preference for undifferentiated neurons, which may explain the devastating complications resulting from congenital cases in comparison with adults and may serve as a possible explanation for the observed auditory neuropathy findings.28,80

In contrast to the auditory neuropathy observed in Zika, HL associated with Ebola and LF is similar to common viral-mediated etiologies of HL and can be easily detected with traditional hearing screening. Prevalence of Ebola- and LF-mediated HL is likely underestimated in this review because of the paucity of studies using objective audiometric measurements. The one study that used objective audiometric testing found a staggering 64.3% of Ebola survivors developed some form of postinfectious HL.19 However, because of the low quality of data presented by these studies, it must be emphasized that these results must be interpreted with caution, highlighting the urgent need for future studies of HL secondary to tropical diseases. Various mechanisms have been proposed for the etiology of post-Ebola syndrome symptoms, depicted by detection of the virus in areas such as the eye and semen, including the persistence of virus in immune-privileged sites leading to a direct cytopathic effect.37,40,81–84 It has been theorized that the penetration of the virus into cerebrospinal fluid may allow passage into the perilymph via the cochlear aqueduct, leading to the development of Ebola-associated HL. Although most cases of LF are thought to be asymptomatic or subclinical, sequelae, including HL, have been noted to occur across all severities of disease.20,62,85–87 The pathogenesis responsible for LF-related HL is poorly understood, and both immunologic and cytopathic mechanisms have been proposed.88,89

Future directions.

Hearing loss is a growing public health concern with lifelong impact. As DALYs and the economic impact secondary to HL continue to increase, it is imperative that steps are taken to address this disability. These results demonstrate that the prevalence of HL associated with Zika, Ebola, and LF infection may be up to 300× greater than common viral etiologies of HL. It is critical that future studies of these tropical infections include objective audiological evaluation using a standard, WHO-supported definition of HL, coupled with longitudinal rescreening to accurately determine the prevalence and fully characterize the natural course of HL secondary to these viruses. Furthermore, future studies of sequelae can provide evidence of causal relationships between these tropical viruses and HL, identify risk factors for diagnosis and prognostication, and elucidate mechanisms leading to HL. Such knowledge is crucial to the development of public health interventions to prevent this understudied disability and improve the quality of life after survival from these devastating and neglected tropical diseases.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIH Research Training Grant #D43 TW009340 funded by the NIH Fogarty International Center, NINDS, NIMH, and NHBLI and serves as background for the World Health Organization World Report on Hearing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hotez PJ, Ferris MT, 2006. The antipoverty vaccines. Vaccine. 24: 5787–5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotez PJ, Molyneux DH, Fenwick A, Kumaresan J, Sachs SE, Sachs JD, Savioli L, 2007. Control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 357: 1018–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotez P, Ottesen E, Fenwick A, Molyneux D, 2006. The neglected tropical diseases: the ancient afflictions of stigma and poverty and the prospects for their control and elimination. Pollard AJ, Finn A, eds. Hot Topics in Infection and Immunity in Children III, Vol. 582 New York, NY: Springer, 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotez PJ, 2008. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2: e230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss MG, 2008. Stigma and the social burden of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2: e237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization , 2008. Guinea: Life after Ebola Has New Meaning for 2 Survivors Now Helping Others. WHO. Available at: http://www.who.int/features/2014/life-after-ebola/en/. Accessed March 6, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.GBD 2016 DALYs, HALE Collaborator , 2017. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390: 1260–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackenzie I, Smith A, 2009. Deafness—the neglected and hidden disability. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 103: 565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators , 2016. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388: 1545–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohr PE, Feldman JJ, Dunbar JL, McConkey-Robbins A, Niparko JK, Rittenhouse RK, Skinner MW, 2000. The societal costs of severe to profound hearing loss in the United States. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 16: 1120–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis JM, Elfenbein J, Schum R, Bentler RA, 1986. Effects of mild and moderate hearing impairments on language, educational, and psychosocial behavior of children. J Speech Hear Disord 51: 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bess FH, Dodd-Murphy J, Parker RA, 1998. Children with minimal sensorineural hearing loss: prevalence, educational performance, and functional status. Ear Hear 19: 339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin FR, 2011. Hearing loss and cognition among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66: 1131–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin FR, et al. 2013. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 173: 293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Dishoeck HA, Bierman TA, 1957. Sudden perceptive deafness and viral infection. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 66: 963–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byl FM, Jr., 1984. Sudden hearing loss: eight years’ experience and suggested prognostic table. Laryngoscope. 94: 647–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffe BF, 1978. Viral causes of sudden inner ear deafness. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 11: 63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leal MC, 2016. Hearing loss in infants with microcephaly and evidence of congenital Zika virus infection—Brazil, November 2015–May 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65: 917–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowe AK, et al. 1999. Clinical, virologic, and immunologic follow-up of convalescent Ebola hemorrhagic fever patients and their household contacts, Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Commission de Lutte contre les Epidémies à Kikwit. J Infect Dis 179 (Suppl 1): S28–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummins D, McCormick JB, Bennett D, Samba JA, Farrar B, Machin SJ, Fisher-Hoch SP, 1990. Acute sensorineural deafness in Lassa fever. JAMA 264: 2093–2096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen BE, Durstenfeld A, Roehm PC, 2014. Viral causes of hearing loss: a review for hearing health professionals. Trends Hear 18: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martins OR, de AL Rodrigues P, dos Santos ACM, Ribeiro EZ, Nery AF, Lima JB, Moreno CC, Silveira ARO, 2017. Achados otológicos em pacientes pós-infecção pelo Zika vírus: estudos de caso. Audiol Commun Res 22, 10.1590/2317-6431-2017-1850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tappe D, Nachtigall S, Kapaun A, Schnitzler P, Günther S, Schmidt-Chanasit J, 2015. Acute Zika virus infection after travel to Malaysian Borneo, September 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 21: 911–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinhaes ES, et al. 2017. Transient hearing loss in adults associated with Zika virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 64: 675–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leal MC, Muniz LF, Caldas Neto SD, van der Linden V, Ramos RC, 2016. Sensorineural hearing loss in a case of congenital Zika virus. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 16: 30126–30127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheeler AC, Ventura CV, Ridenour T, Toth D, Nobrega LL, Silva de Souza Dantas LC, Rocha C, Bailey DB, Jr, Ventura LO, 2018. Skills attained by infants with congenital Zika syndrome: pilot data from Brazil. PLoS One 13: e0201495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satterfield-Nash A, et al. 2017. Health and development at age 19–24 Months of 19 children who were born with microcephaly and laboratory evidence of congenital Zika virus infection during the 2015 Zika virus outbreak—Brazil, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66: 1347–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos VS, Oliveira SJG, Gurgel RQ, Lima DRR, Dos Santos CA, Martins-Filho PRS, 2017. Case report: microcephaly in twins due to the Zika virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 97: 151–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Microcephaly Epidemic Research Group , 2016. Microcephaly in infants, Pernambuco State, Brazil, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 22: 1090–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Laval F, et al. 2018. Evolution of symptoms and quality of life during Zika virus infection: a 1-year prospective cohort study. J Clin Virol 109: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ventura CV, Consortium Investigators et al. 2018. First locally acquired congenital Zika syndrome case in the United States: neonatal clinical manifestations. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 49: e93-e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.França TLB, Medeiros WR, Souza NL, Longo E, Pereira SA, França TBO, Sousa KG, 2018. Growth and development of children with microcephaly associated with congenital Zika virus syndrome in Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15: E1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vianna RAO, et al. 2019. Children born to mothers with rash during Zika virus epidemic in Brazil: first 18 Months of life. J Trop Pediatr 19: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calle-Giraldo JP, et al. 2019. Outcomes of congenital Zika virus infection during an outbreak in Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Pediatr Infect Dis J 38: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wheeler AC, 2018. Development of infants with congenital Zika syndrome: what do we know and what can we expect? Pediatrics. 141 (Suppl 2): S154–S160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs M, et al. 2016. Late Ebola virus relapse causing meningoencephalitis: a case report. Lancet 388:498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mattia JG, et al. 2016. Early clinical sequelae of Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 16: 3 31–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qureshi AI, Chughtai M, Loua TO, Pe Kolie J, Camara HF, Ishfaq MF, N’Dour CT, Beavogui K, 2015. Study of Ebola virus disease survivors in Guinea. Clin Infect Dis 61: 1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiffany A, Vetter P, Mattia J, Dayer JA, Bartsch M, Kasztura M, Sterk E, Tijerino AM, Kaiser L, Ciglenecki L, Ebola virus disease complications as experienced by survivors in Sierra Leone. Clin Infect Dis 62: 1360–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etard JF, et al. 2017. Multidisciplinary assessment of post-Ebola sequelae in Guinea (Postebogui): an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 17: 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shantha JG, Crozier I, Hayek BR, Bruce BB, Gargu C, Brown J, Fankhauser J, Yeh S, 2017. Ophthalmic manifestations and causes of vision impairment in Ebola virus disease survivors in monrovia, Liberia. Ophthalmology 124: 170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bwaka MA, et al. 1999. Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo: clinical observations in 103 patients. J Infect Dis 179 (Suppl 1): S1–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark DV, et al. 2015. Long-term sequelae after Ebola virus disease in Bundibugyo, Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 15: 905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jagadesh S, Sevalie S, Fatoma R, Sesay F, Sahr F, Faragher B, Semple MG, Fletcher TE, Weigel R, Scott JT. 2018. Disability among Ebola survivors and their close contacts in Sierra Leone: a retrospective case-controlled cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 66: 131–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson HW, Amo-Addae M, Kenu E, Ilesanmi OS, Ameme DK, Sackey SO, 2018. Post-Ebola syndrome among Ebola virus disease survivors in Montserrado County, Liberia 2016. Biomed Res Int 2018: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nanyonga M, Saidu J, Ramsay A, Shindo N, Bausch DG. 2016. Sequelae of Ebola virus disease, Kenema district, Sierra Leone. Clin Infect Dis 62: 125–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelly JD, et al. 2018. Neurological, cognitive, and psychological findings among survivors of Ebola virus disease from the 1995 Ebola outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of Congo: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis 68: 1388–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hereth-Hebert E, et al. 2017. Ocular complications in survivors of the Ebola outbreak in Guinea. Am J Ophthalmol 175: 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fallah MP, Skrip LA, Dahn BT, Nyenswah TG, Flumo H, Glayweon M, Lorseh TL, Kaler SG, Higgs ES, Galvani AP, 2016. Pregnancy outcomes in Liberian women who conceived after recovery from Ebola virus disease. Lancet Glob Health 4: e678–e679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wing K, et al. 2018. Surviving Ebola: a historical cohort study of Ebola mortality and survival in Sierra Leone 2014–2015. PLoS One 13: e0209655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Overholt L, et al. 2018. Stigma and Ebola survivorship in Liberia: results from a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One 13: e0206595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howlett PJ, et al. 2018. Case series of severe neurologic sequelae of Ebola virus disease during epidemic, Sierra Leone. Emerg Infect Dis 24: 1412–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de St Maurice A, et al. 2018. Care of Ebola survivors and factors associated with clinical sequelae—Monrovia, Liberia. Open Forum Infect Dis 5: ofy239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The PREVAIL III Study Group et al. 2019. A longitudinal study of Ebola sequelae in Liberia. N Engl J Med 380: 924–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kelly JD, et al. 2019. Ebola virus disease-related stigma among survivors declined in Liberia over an 18-month, post-outbreak period: an observational cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13: e0007185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okokhere PO, Ibekwe TS, Akpede GO, 2009. Sensorineural hearing loss in Lassa fever: two case reports. J Med Case Rep 3: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grundy D, Bowen ETW, Lloyed G, 1980. Isolated case of Lassa fever in Zaria, Northern Nigeria. Lancet 316: 649–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choi MJ, et al. 2018. A case of Lassa fever diagnosed at a community hospital—Minnesota 2014. Open Forum Infect Dis 5: ofy131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grahn A, et al. 2016. Imported case of Lassa fever in Sweden with encephalopathy and sensorineural hearing deficit. Open Forum Infect Dis 3: ofw198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCormick JB, King IJ, Webb PA, Johnson KM, O’Sullivan R, Smith ES, Trippel S, Tong TC, 1987. A case-control study of the clinical diagnosis and course of Lassa fever. J Infect Dis 155: 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Macher AM, Wolfe MS, 2006. Historical Lassa fever reports and 30-year clinical update. Emerg Infect Dis 12: 835–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ibekwe TS, Okokhere PO, Asogun D, Blackie FF, Nwegbu MM, Wahab KW, Omilabu SA, Akpede GO, 2011. Early-onset sensorineural hearing loss in Lassa fever. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 268: 197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.White HA, 1972. Lassa fever: a study of 23 hospital cases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 66: 390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mertens PE, Patton R, Baum JJ, Monath TP, 1973. Clinical presentation of Lassa fever cases during the hospital epidemic at Zorzor, Liberia, March-April 1972. Am J Trop Med Hyg 22:780–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Okokhere P, et al. 2018. Clinical and laboratory predictors of assa fever outcome in a dedicated treatment facility in Nigeria: a retrospective, observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 18: 684–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Günther S, Weisner B, Roth A, Grewing T, Asper M, Drosten C, Emmerich P, Petersen J, Wilczek M, Schmitz H, 2001. Lassa fever encephalopathy: Lassa virus in cerebrospinal fluid but not in serum. J Infect Dis 184: 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frame JD, 1989. Clinical features of Lassa fever in Liberia. Rev Infect Dis 11: S783–S789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frame JD, Monson MH, Cole AK, Alexander S, Jahrling PB, Serwint JR, 1987. Pediatric Lassa fever: a review of 33 Liberian cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg 36: 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hirabayashi Y, Oka S, Goto H, Shimada K, Kurata T, Fisher-Hoch SP, McCormick JB, 1988. An imported case of Lassa fever with late appearance of polyserositis. J Infect Dis 158: 872–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arlinger S, 2003. Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss—a review. Int J Audiol 42 (Suppl 2): 17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kvam MH, Loeb M, Tambs K, 2007. Mental health in deaf adults: symptoms of anxiety and depression among hearing and deaf individuals. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ 12: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tambs K, 2004. Moderate effects of hearing loss on mental health and subjective well-being: results from the Nord-Trøndelag hearing loss study. Psychosom Med 6: 776–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shin HY, Hwang HJ, 2017. Mental health of the people with hearing impairment in Korea: a population-based cross-sectional study. Korean J Fam Med 38: 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li CM, Zhang X, Hoffman HJ, Cotch MF, Themann CL, Wilson MR, 2014. Hearing impairment associated with depression in us adults, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2010. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 140: 293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parra VM, Matas CG, Neves IF, 2003. Estudo de caso: neuropatia auditiva. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringol 69: 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Probst R, Lonsbury-Martin BL, Martin GK, 1991. A review of otoacoustic emissions. J Acoust Soc Am 89: 2027–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wiwanitkit V, 2017. Hearing loss in congenital Zika virus. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 83: 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nem de Oliveira Souza I, et al. 2018. Acute and chronic neurological consequences of early-life Zika virus infection in mice. Sci Transl Med 10: eaar2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Racicot K, VanOeveren S, Alberts A, 2017. Viral hijacking of formins in neurodevelopmental pathologies. Trends Mol Med 23: 778–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guevara JG, Agarwal-Sinha S, 2018. Ocular abnormalities in congenital Zika syndrome: a case report, and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 12: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vetter P, Kaiser L, Schibler M, Ciglenecki I, Bausch DG, 2016. Sequelae of Ebola virus disease: the emergency within the emergency. Lancet Infect Dis 16: e82–e91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spengler JR, Prescott J, Feldmann H, Spiropoulou CF, 2017. Human immune system mouse models of Ebola virus infection. Curr Opin Virol 25: 90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Younan P, Iampietro M, Bukreyev A, 2018. Disabling of lymphocyte immune response by Ebola virus. PLoS Pathog 14: e1006932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yeh S, Shantha JG, Hayek B, Crozier I, Smith JR, 2018. Clinical manifestations and pathogenesis of uveitis in Ebola virus disease survivors. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 26: 1128–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cashman KA, Wilkinson ER, Facemire PR, Bell TM, Shaia CI, Schmaljohn CS, 2018. Autoimmune associated systemic vasculitis as the cause of sudden onset bilateral sensorineural hearing loss following Lassa virus exposure in a cynomolgus macaque deafness model. mBio 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cashman KA, et al. 2017. A DNA vaccine delivered by dermal electroporation fully protects cynomolgus macaques against Lassa fever. Hum Vaccin Immunother 13: 2902–2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yun SI, Lee YM, 2017. Zika virus: an emerging flavivirus. J Microbiol 55: 204–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yun NE, et al. 2015. Animal model of sensorineural hearing loss associated with Lassa virus infection. J Virol 90: 2920–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rybak LP, 1990. Deafness associated with Lassa fever. JAMA 264: 2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]