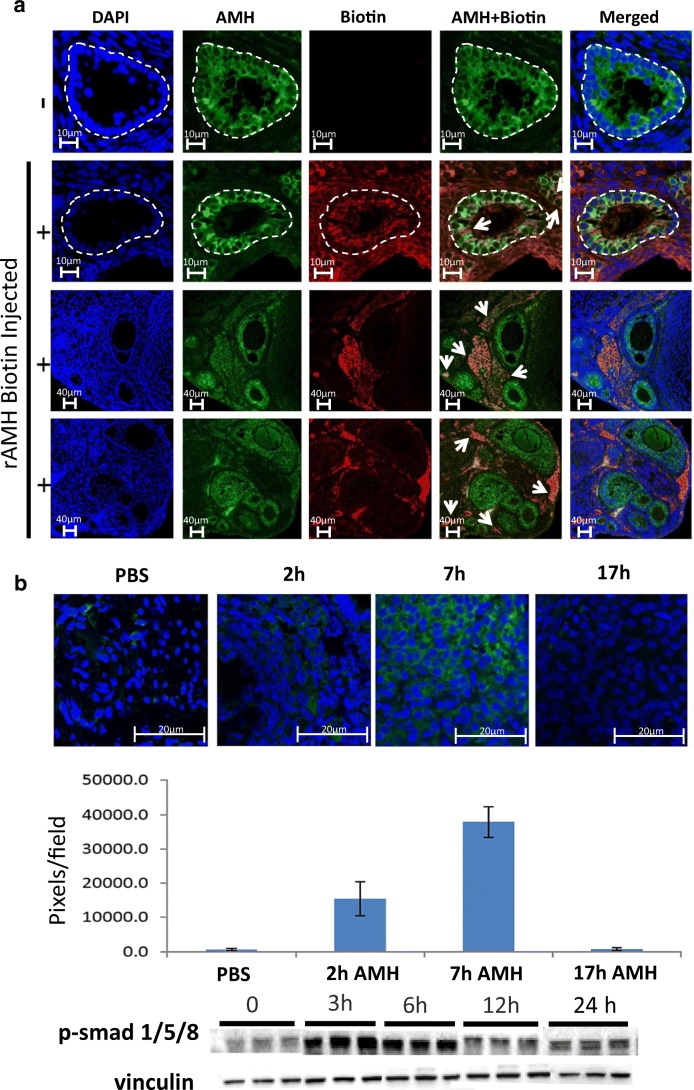

Fig. 1.

Bioactivity and IP delivery of rAMH. (a) rAMH was biotin-labelled and injected IP into 6-week-old female mice (10 μg per mouse). Histological analysis was conducted on ovaries removed 6 h post injection (n = 4). PBS-injected (row 1) and biotin-rAMH-injected (rows 2–4) samples were stained with AMH (green) and biotin (red), and DAPI (blue) antibodies. Yellow staining indicates merged AMH and biotin, representing exogenous rAMH. White circles outline the small growing follicles showing the presence of endogenous and exogenous AMH in the cytoplasm of the granulosa cells and in stromal cells in the surrounding tissue. Biotin-labelled exogenous rAMH can be clearly seen in the cytoplasm of granulosa cells of growing follicles (marked by arrows in row 2) and in areas of the ovarian stroma (marked by arrows in rows 3 and 4). Magnification × 63. (b) Mature 6-week-old female mice were treated with 4 weekly doses of 75 mg/kg Cy, a dose which reduced ovarian follicle reserve to below 10% of normal values in our previous studies [9]. Six months later, when almost the entire ovarian reserve was depleted and endogenous levels of AMH were close to non-existent, the mice were injected IP with 10 μg rAMH (unlabelled) (n = 3 mice per timepoint). Histological analysis was conducted on ovaries removed 0, 2, 7, and 17 h post rAMH injection. Samples were stained with AMH (green) antibody and representative images from 4 ovaries from each group were analysed with ImageJ software. Magnification × 63. c Western blot analysis for p-SMAD 1,5,8 and housekeeping protein, vinculin, was conducted on ovaries from 6-week-old mice removed 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post rAMH injection (n = 3 mice per timepoint)