Abstract

Purpose

To pilot test the impact of the ICAN Discussion Aid on clinical encounters.

Methods

A pre–post study involving 11 clinicians and 100 patients was conducted at two primary care clinics within a single health system in the Midwest. The study examined clinicians’ perceptions about ICAN feasibility, patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions about encounter success, videographic differences in encounter topics, and medication adherence 6 months after an ICAN encounter.

Results

39/40 control encounters and 45/60 ICAN encounters yielded usable data. Clinicians reported ICAN use was feasible. In ICAN encounters, patients discussed diet, being active and taking medications more. Clinicians scored themselves poorer regarding visit success than their patients scored them; this effect was more pronounced in ICAN encounters. ICAN did not improve 6-month medication adherence or lengthen visits.

Conclusion

This pilot study suggests that using ICAN in primary care is feasible, efficient and capable of modifying conversations. With lessons learned in this pilot, we are conducting a randomised trial of ICAN versus usual care in diverse clinical settings.

Trial registration number

Keywords: patient-centred care, minimally disruptive medicine, healthcare communication, chronic disease, multimorbidity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Small before–after pilot study limiting the ability to draw statistical inferences that would be possible in a larger trial with a randomised design.

Not powered to assess clinical significance for patient-reported outcomes nor prescription adherence; lack of difference found is not indicative of one not existing.

Single healthcare system in the Midwest with a fairly homogenous patient population limiting generalisability.

Small size was a strength in allowing us to pursue video recording of all encounters, allowing the deeper exploration of ICAN’s impact on conversations and additional training needs for future implementation and testing.

Introduction

Estimates in 2013 indicated that 117 million, or approximately half of adults in the USA had one or more chronic conditions,1 while 26% of adults in the USA had multiple chronic conditions (MCC).2 Patients living with chronic conditions must cope with the burden of illness and additionally invest time and energy to comprehend, manage and access professional healthcare—the work of being a patient. If this work is not carefully managed and monitored, patients may experience treatment burden.3 4

Treatment burden often goes unnoticed, as clinical practice guidelines focus on managing individual conditions, without explicit consideration of comorbidities or the patient’s values, preferences and context.5 If implemented in this way, the application of all guideline recommendations may overwhelm patients.6–8 Similarly, clinical practice does not often acknowledge patients’ potentially limited capacity to handle complexity of life and healthcare work, which leads to the prescription of treatment plans that require capacity of patients and their caregivers that they may not have.9 10

This situation impacts patients and families, and has also led to burnt-out clinicians.11 Beyond medical complexity described above, clinicians also need to consider non-medical complexity (eg, difficulty affording medications, unstable housing and problematic family dynamics), and the body of literature is growing to show that clinicians have difficulty with conversations where medical and non-medical complexity intersect.12–16

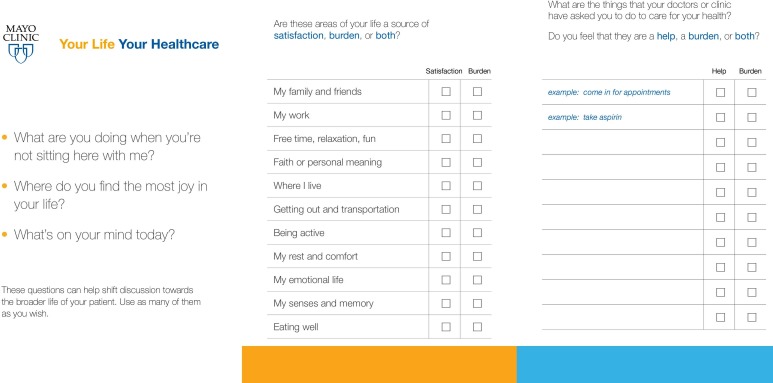

The ICAN Discussion Aid (figure 1) was developed to address these problems, with the aim of enabling the discussion of patient workload, capacity and treatment burden within the time constraints of busy primary care visits.17 The process to develop ICAN is described in full elsewhere.17 Briefly, it was developed using a robust, iterative, user-centred design process, previously used to develop decision aids18 and was grounded in the Cumulative Complexity Model, which states that patients living with chronic illness must enact both patient and life work with limited capacity.19 When workload exceeds patient capacity, it affects patients’ abilities to access and use healthcare and enact self-care, in turn affecting their health outcomes.19 In addition to worsening health outcomes, unaddressed workload–capacity imbalance can lead to a vicious cycle of added treatment burden and illness burden.19

Figure 1.

ICAN discussion aid.

To date, the ICAN discussion aid remains untested in terms of its impact on the discussion of patient workload, capacity, and treatment burden in the clinical encounter. We hypothesise that if ICAN proves feasible in busy primary care and positively impacts the clinical encounter with greater discussion of patients’ context, it could spark treatment plans that better fit patients’ lives, with downstream impact on patient health outcomes and quality of life.

Aim

We aimed to evaluate the feasibility of using the ICAN Discussion Aid in primary care and to estimate its impact on clinical care, including patient-perceived and clinician-perceived success of visits, length of visits, and topics of conversation.

Methods

To pilot test the ICAN Discussion Aid, we conducted a pretest versus post-test intervention study.

Participant eligibility and recruitment

Clinicians were recruited from two clinical sites in the Midwestern United States and were eligible for participation if they regularly saw patients with chronic conditions. Clinicians were consented for participation either at a lunch-hour clinical practice meeting or immediately before their first eligible patient. Clinicians were consented by the principal investigator (KRB) or a trained study coordinator. Adult patients were eligible if they had one or more chronic conditions, no major barriers to consent (e.g., cognitive impairment), and were seeing a clinician who had agreed to participate. To assess for barriers to consent, we used the electronic medical record to look for keywords such as language, cognitive function, serious vision/hearing impairment, and so on, and also confirmed with the primary care clinician that the patients did not have any of the listed barriers to consent and were appropriate to include in the study. Patients were approached immediately before the encounter with their clinician by a trained study coordinator.

Study procedures

After both clinician and patient were enrolled in the study, a trained study coordinator set up a small video camera (i.e., FlipCam, GoPro) to record the clinic visit. Patients and clinicians could turn the video camera off at any time if they felt uncomfortable, and the video camera was always turned around or off during physical examinations. Following the encounter, both patient and clinician were given a survey to complete immediately or return in a postage-paid return envelope. The study coordinator followed up on surveys not returned within one week. The first 40 clinical encounters were usual care. After the first 40 encounters, clinicians were then trained during a standing meeting or individually on how to use the ICAN Discussion Aid. The remaining 60 clinical encounters were intended to be ICAN encounters.

Intervention: the ICAN Discussion Aid

The study coordinator provided instructions for the patient to complete the ICAN Discussion Aid (figure 1) before the clinician entered the room. When the clinician entered the room, he or she would select one of three opening questions to elicit responses from the patient, and would then explore the information that the patient provided in ICAN by asking ‘What stands out to you on this sheet you filled?’ Clinicians were instructed to discuss that issue alone and connect it to the reason for the visit that day. Clinical conversation was expected to proceed as usual with incorporation of the ICAN information.

Measures

Clinician degree, position and gender were collected at baseline. Patient characteristics of age, sex and marital status were abstracted from the medical record. To assess perceived success of the encounter, we used the consultation care measure (CCM), a valid and discriminating tool to measure communication and partnership within a single encounter, previously correlated with patient satisfaction, enablement and reduced symptom burden.20 The measure asks patients to what extent they agree with statements about the doctor such as he/she ‘was interested in what I thought the problem was’.20 For clinician surveys, we used a modified version of the patient CCM, adjusted to the clinician perspective, which was not previously validated. For example, the patient might be asked the extent to which they felt the clinician ‘was careful to explain the plan of treatment’. Whereas the clinician would be asked the extent to which they agreed with the statement that they felt that they ‘were careful to explain the plan of treatment’. To assess feasibility of ICAN use, we asked clinicians to report how easy or difficult the aid was to use in their encounter on a 5-point scale, from very easy to very difficult. If clinicians marked difficult or very difficult, they were prompted to write a brief description of why. To assess adherence, patients pharmaceutical records were collected as a means to provide estimates of baseline adherence among patients in this population, and of whether using ICAN potentially affects adherence through the tailoring of patient care plans to their life context. Given the hypothesis generating nature of the adherence data, the methods and results are provided in online supplementary appendix 1.

bmjopen-2019-029105supp001.pdf (115.4KB, pdf)

Videographic coding scheme

To assess ICAN’s impact on clinical conversation topics, we created an a priori video coding scheme, in which we coded each instance where the following topics were brought up: family, friends, free time, faith, living situation, being active, rest, comfort, emotional life, senses, memory, eating well, taking medications, making appointments, getting to appointments, administrative treatment work (eg, dealing with insurance/billing, communicating with pharmacies), prescribed behaviours (eg, getting mammograms, exercising a certain number of minutes per week) and other treatment work (ie, work that the patient was asked to do but that did not fit into these other categories). Life issues listed in the coding scheme were those shown on ICAN and previously illustrated as the important components of patient capacity from earlier work.17 21 Treatment burden issues listed in the coding scheme were derived from typical issues listed in the development of ICAN and a taxonomy of treatment burden.17 22 We also coded for opening questions typically used in ICAN, designed to elicit the existence of competing priorities that could potentially limit the capacity for self-care or treatment, sources of joy in patients’ lives and immediate concerns (medical and non-medical). To assess impact on length of visit, we compared lengths of video recording.

Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (SAS Institute, V.9.4) and Stata (StataCorp, Release 15, College Station, Texas, USA). Videographic coding was done using Noldus Observer XT (V.11, Leesburg, Virginia, USA). Patient and clinical encounter characteristics were compared between ICAN and control encounters using a t-test for continuous variables and a χ2 test for categorical variables. To explore differences in patient-perceived and clinician-perceived success of an encounter, we subtracted unadjusted clinician scores from unadjusted patient scores, and tested for changes in the perceived success gap between ICAN and control encounters using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. To test for differences across issues discussed in videos where patients and clinicians used ICAN versus those recorded in control encounters, we used a negative binomial model accounting for clustering within clinicians.

Patient and public involvement

The Knowledge and Evaluation Research Unit Patient Advisory Group participated in the design of the ICAN discussion aid, ensuring its relevance to patients living with chronic conditions and its ease of use. They were not consulted for the research design of the pilot study.

Results

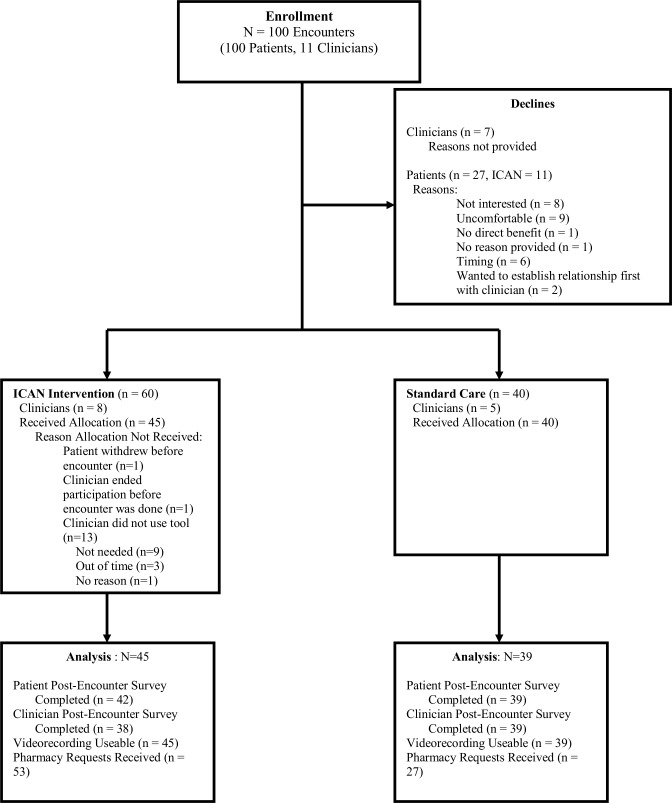

Eleven clinicians were enrolled from two primary care clinics within the Midwest, USA starting in October 2015. Seven clinicians approached declined enrolment, without providing a reason. The clinicians were primarily women (n=7, 64%) and were primarily physicians, with one nurse practitioner and two physician assistants. Patient enrolment began October 2015 and ended February 2017. One hundred patients consented to participate (ICAN n=60). Detailed enrolment information is depicted in figure 2. Of the 11 clinicians participating, one had all control encounters and five had all ICAN encounters. Patient characteristics are depicted in table 1. Encounter length did not significantly differ between ICAN and control encounters.

Figure 2.

Detailed enrolment information.

Table 1.

Patient and encounter characteristics*

| ICAN (n=57†) |

Preintervention (n=40) |

Total (n=97) |

P value | |

| Sex | 0.09 | |||

| Female | 40 (70.2%) | 34 (85.0%) | 74 (76.3%) | |

| Age: mean (SD) | 62.7 (12.0) | 66.8 (15.0) | 64.4 (13.4) | 0.05 |

| Marital status | 0.37 | |||

| Divorced | 11 (19.3%) | 3 (7.5%) | 14 (14.4%) | |

| Married | 36 (63.2%) | 27 (67.5%) | 63 (64.9%) | |

| Single | 5 (8.8%) | 4 (10.0%) | 9 (9.3%) | |

| Widowed | 5 (8.8%) | 6 (15.0%) | 11 (11.3%) | |

| Length of encounter (minutes): mean (SD) | 31.6 (13.4) | 34.5 (11.7) | 32.9 (12.7) | 0.25 |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 31.3 (19, 41) | 34.3 (25, 44) | 33.6 (22, 42) |

*All enrolled patients.

†Three patients in intervention missing data on characteristics.

Clinician-reported feasibility of ICAN

Clinicians found the tool feasible to use in the majority of encounters. 62% reported it very easy or easy, 32% reported it as neither easy nor difficult and 5% reported it was difficult to use in that encounter. There were two encounters where it was reported as difficult by different clinicians. For one encounter, the clinician stated, ‘Unfortunately, this made her appointment go over by about 30 min. It was good we discussed issues with the portal [an online platform that allows patients to access their health information] and her life and stressors but it wasn’t a big concern (why it wasn’t a reason for the appointment) but we spent a good deal of time on it’. On further review of this video, it appears that the primary reason that the encounter lasted substantially longer than planned was a lack of fidelity to ICAN training. After the clinician asked the patient what stood out to her from ICAN, she continued to elicit information about each burden listed by the patient, rather than connect the patient’s response to the remainder of the clinical visit. Addressing the two key issues, the patient brought up, work stress and being active, took approximately five and a half minutes in total. Following that, the clinician spent an additional five and a half minutes reviewing the other items on the tool.

In the second encounter, the clinician stated, ‘I enjoy the learning and conversation obtained from form [sic] but didn’t have the extra time in schedule [sic] necessary to address each issue—easily added another 15–20 min to appointment’. In this encounter, the patient indicated that her emotional life was both a source of satisfaction and a burden. The clinician inquired further and thus provided the patient with an opportunity to talk about her prolonged grief after the loss of her spouse and her concerns about possible depression. In response, the clinician screened the patient for potential depression. Total time using the tool and discussing that issue took four min of the total visit. The patient was scheduled for a 45 min general medical examination, and the total video recorded visit time was 26 min, which did not include the physical examination at the end of the encounter.

Survey results

We did not find any items with significant differences between patients in either cohort for the CCM (table 2). When comparing patients and clinicians across the CCM, among the items that overlapped, clinicians tended to score themselves poorer than patients. This was more prevalent when the ICAN tool was used (table 3).

Table 2.

Consultation care measure patient scores

| Overall score | ICAN (n=42) |

Preintervention (n=39) |

Total (n=81) |

| Mean (SD) | 29.7 (11.0) | 28.6 (12.4) | 29.2 (11.6) |

| Median (range) | 25 (21, 62) | 23 (21, 74) | 24 (21, 74) |

| Adjusted mean* (95% CI) | 31.5 (24.6 to 38.5) | 34.6 (29.3 to 42.9) |

*Adjusted by clinician clustering; lower scores=better.

Table 3.

Clinician–patient difference in individual consultation care measure (CCM) scores

| ICAN (n=38)* | Preintervention (n=39)* | P value | |

| 1/E: careful to explain | 0.87 (0.52, 1.22) | 0.64 (0.32, 0.96) | 0.33 |

| 2/F: was sympathetic | 0.97 (0.57, 1.37) | 0.54 (0.19, 0.89) | 0.09 |

| 3/H: discussed and agreed together what problem was | 0.97 (0.61, 1.33) | 0.51 (0.19, 0.84) | 0.047 |

| 4/K: discussed and agreed on plan of treatment | 0.84 (0.51, 1.17) | 0.59 (0.25, 0.93) | 0.26 |

| 5/M: understood emotional needs | 0.97 (0.43, 1.52) | 0.77 (0.39, 1.15) | 0.31 |

| 6/N: confident knows patient history | 0.66 (0.23, 1.09) | 0.77 (0.40, 1.14) | 0.91 |

| 7/T: interested in effect of problem on family and personal life | 0.68 (0.22, 1.15) | 0.64 (0.27, 1.02) | 0.73 |

| 8/U: interested in effect of problem on everyday life | 0.82 (0.35, 1.29) | 0.74 (0.39, 1.10) | 0.60 |

Mean (95% CI), p value Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

*Difference in scores calculated as clinician score minus patient score for encounter. Higher scores correspond to lower performance on the CCM tool.

Videographic results

Issues discussed during clinical encounters did significantly differ between ICAN and control encounters in multiple domains (table 4). Specifically, discussions about being active, diet and taking medications were discussed significantly more frequently in ICAN encounters. Discussions about administrative treatment work, other treatment work, family, living arrangements and comfort were discussed significantly less frequently in ICAN encounters. We noticed that often topics about family were used as conversation fillers in control encounters, whereas there may have been less room for this when patients were prompted to bring up issues that mattered most to them.

Table 4.

Videographic analysis of issues discussed by patients and clinicians

| Behaviours* | All encounters (n=84/ICAN=45) | Patients (n=84) | Clinicians (n=84) | |||

| IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | |

| More likely with ICAN | ||||||

| Being active | 1.52 (1.09 to 2.11) | 0.01 | 1.58 (1.12 to 2.22) | 0.008 | 1.45 (0.95 to 2.21) | 0.09 |

| Taking medications | 1.22 (0.99 to 1.51) | 0.06 | 1.42 (1.20 to 1.67) | <0.0001 | 1.12 (0.85 to 1.46) | 0.42 |

| Diet | 2.02 (1.22 to 3.32) | 0.005 | 2.32 (1.39 to 3.88) | 0.001 | 1.61 (0.93 to 2.79) | 0.09 |

| Competing priorities | 14.46 (4.00 to 52.24) | <0.0001 | –† | – | 10.91 (3.63 to 32.73) | <0.0001 |

| Less likely with ICAN | ||||||

| Other admin | 0.56 (0.39 to 0.82) | 0.002 | 0.74 (0.48 to 1.13) | 0.16 | 0.47 (0.33 to 0.69) | <0.0001 |

| Family | 0.57 (0.36 to 0.90) | 0.02 | 0.66 (0.42 to 1.03) | 0.05 | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.75) | 0.002 |

| Faith | 0.59 (0.42 to 0.82) | 0.002 | 0.78 (0.44 to 1.39) | 0.41 | 0.36 (0.12 to 1.05) | 0.06 |

| Senses | 0.55 (0.30 to 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.65 (0.35 to 1.22) | 0.18 | 0.44 (0.23 to 0.87) | 0.02 |

| No difference with ICAN | ||||||

| Other treatment work | 0.90 (0.65 to 1.24) | 0.52 | 1.07 (0.71 to 1.63) | 0.74 | 0.77 (0.59 to 1.01) | 0.06 |

| Immediate concerns | 1.11 (0.69 to 1.76) | 0.68 | 1.62 (0.86 to 3.06) | 0.14 | 0.90 (0.60 to 1.37) | 0.64 |

| Joy | –† | – | –† | – | –† | – |

| Where I live | 0.82 (0.50 to 1.35) | 0.44 | 1.09 (0.66 to 1.80) | 0.75 | 0.58 (0.32 to 1.04) | 0.07 |

| Comfort | 0.76 (0.50 to 1.16) | 0.20 | 0.90 (0.62 to 1.33) | 0.61 | 0.63 (0.39 to 1.01) | 0.05 |

| Free time | 1.08 (0.54 to 2.16) | 0.82 | 1.20 (0.60 to 2.40) | 0.61 | 0.96 (0.45 to 2.04) | 0.92 |

| Making appointments | 0.76 (0.50 to 1.16) | 0.21 | 0.77 (0.49 to 1.23) | 0.27 | 0.75 (0.49 to 1.15) | 0.18 |

| Prescribed behaviours | 0.84 (0.45 to 1.58) | 0.59 | 0.96 (0.57 to 1.64) | 0.89 | 0.80 (0.40 to 1.61) | 0.53 |

| Friends | 0.75 (0.33 to 1.66) | 0.47 | 0.65 (0.30 to 1.40) | 0.27 | 1.41 (0.52 to 3.75) | 0.49 |

| Getting to appointments | 1.24 (0.74 to 2.08) | 0.41 | 1.34 (0.76 to 2.36) | 0.32 | 1.09 (0.60 to 2.00) | 0.78 |

| Work | 0.85 (0.60 to 1.220 | 0.39 | 1.05 (0.75 to 1.47) | 0.80 | 0.62 (0.38 to 1.02) | 0.06 |

| Rest | 0.89 (0.52 to 1.54) | 0.68 | 0.92 (0.52 to 1.59) | 0.75 | 0.87 (0.46 to 1.64) | 0.67 |

| Emotional life | 1.23 (0.54 to 2.80) | 0.63 | 1.56 (0.64 to 3.83) | 0.33 | 1.03 (0.41 to 2.59) | 0.95 |

| Volunteer | 0.85 (0.30 to 2.38) | 0.76 | 0.57 (0.16 to 2.04) | 0.39 | –† | – |

| Personal meaning | 2.39 (0.18 to 32.56) | 0.51 | 2.39 (0.18 to 31.56) | 0.51 | –† | – |

| School | †– | – | –† | – | –† | – |

| Memory | 1.98 (0.70 to 5.63) | 0.20 | 2.41 (0.71 to 8.25) | 0.1596 | 0.80 (0.30 to 2.13) | 0.65 |

>1 means more occurrences in ICAN encounters, <1 fewer occurrences in ICAN encounters.

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

*Adjusted for gender, age at enrolment, length of encounter and clustering around shared clinicians.

†Insufficient data for analysis.

IRR, Incidence rate ratio.

Discussion and conclusion

Summary of findings

Within this pilot trial, clinicians found the ICAN discussion aid to be a tool they could feasibly adopt into everyday practice and which did not impact the length of the visit. Patients discussed diet, being active and taking medications more often in ICAN encounters. Additionally, clinicians elicited competing priorities using ICAN opening questions that were never elicited during the opening of control encounters. While clinicians rated the perceived success of their encounters poorer than their patients (CCM score), and the gap between patient-perceived and clinician-perceived success was larger ICAN encounters, the difference was not significant. No difference was seen for adherence to prescription medications.

Limitations and strengths

These findings cannot be interpreted without considering the limitations in this study design. First, this study was a small before–after pilot study which limits our ability to draw statistical inferences that would be possible in a larger trial with a randomised design. The study was not powered to assess clinical significance for patient-reported outcomes nor prescription adherence and a lack of difference found is not indicative of one not existing. Furthermore, the study occurred within a single healthcare system in the Midwest with a fairly homogenous patient population of mostly high or middle socioeconomic status, which limits the generalisability of the specific changes in topics present in ICAN conversations versus usual care conversations. However, the small size of the study allowed us to pursue video recording of all encounters, which allowed for the deeper exploration of ICAN’s impact on conversations and to point to additional needs for future implementation and testing of ICAN in practice that would have been more difficult in a larger multisite study.

Missing data

Detailed missing data information is depicted in figure 2 and should be considered when interpreting the study’s findings. 39/40 baseline encounters yielded usable data. One survey was unreturned and one encounter’s videographic coding was lost due to technical error. 45/60 follow-up encounters yielded usable data. Fifteen videos during the intervention period were excluded from analyses because although the clinician had been trained in using ICAN and intended to use it in the encounter, they did not use the tool during the encounter. This occurred for a variety of reasons including that the patient brought up more pressing concerns for that day that made the clinician feel the ICAN tool was no longer appropriate for that encounter or the clinician simply forgot to use the tool. Consent to pharmacy record review was an optional portion of the study, therefore reducing the number of profiles available. For all patients that consented to this optional portion, pharmacy records were requested. However, in some cases, the pharmacy did not return a profile for the patient after two request attempts, whereas in other cases, the patient did not have any active prescriptions at the pharmacy on file for chronic conditions.

Practice implications

Feasibility of ICAN use is an important finding on its own, given previously reported challenges by clinicians in providing patient-centred care and participating in shared decision-making for populations living with MCC.23 Furthermore, the difference in the topics brought up in ICAN encounters suggests that patients are indeed more likely to be able to voice their topics of choice, in an area where poor communication has been a noted frustration among patients.24 Diet, being active and taking medications are not surprising topics to be most important to patients in this setting and population (suburban, Midwest, academic medical centre). However, these topics have been noted as important treatment burden factors for patients in other diverse samples; patients noted that they were aware their clinicians wanted them to eat healthier or exercise more frequently, but important barriers existed of which their clinicians were unaware.25 Furthermore, in a previous study of patient–clinician concordance, patients were more likely than clinicians to rank being active as one of their top three health concerns.26 Future research should examine whether the topics discussed more often are different in other clinical settings (eg, rural and urban), with different populations (eg, unsalaried clinicians, underserved patients), and what clinicians can do in clinical encounters with this information.

Ultimately, the discussion of topics of greater importance to patients and their competing priorities is important as it could lead to better tailoring of treatment plans to patients’ context, improving patients’ workload–capacity balance in managing chronic illness. As mentioned earlier, the Cumulative Complexity Model postulates that workload–capacity balance impacts patients’ abilities to access and use healthcare and enact self-care, with downstream impact on their health outcomes.19 Furthermore, communication models, such as the one proposed by Street et al, have postulated the pathways from patient–clinician communication to patient outcomes.27 For example, Street’s model illustrates that communication functions supported by ICAN such as managing uncertainty, fostering relationships and enabling self-management can impact proximal outcomes such as patient trust and ‘feeling known’, with downstream consequences on self-care skills, adherence and ultimately health outcomes.27 ICAN is a general discussion aid for use in chronic illness, intended to provide insight into the personal, social, material and spiritual aspects of the patient’s situation; it can be used in conjunction with the many available decision-specific conversation aids.28 For example, an ICAN conversation may illuminate that a patient finds their overall medication regimen particularly burdensome, and this may spark a treatment-specific conversation about choosing a different treatment in replacement of a current one or inform the decision to add or not add another medication to the list. A good example of the use of ICAN and a treatment decision aid is available on the web.29 Used in this way, clinicians may fully understand patients’ competing priorities as well as treatment-specific values and preferences, and therefore, be able to co-create with them treatment plans that fit their context and allow them to lead quality lives to the fullest extent.

Examining the two encounters noted as difficult for clinicians yielded important information about ICAN implementation challenges. The encounter where additional time was used to discuss all ICAN items suggests that additional training may be needed for clinicians to illustrate how to connect the initial question of ‘What stands out to you?’ to the clinical reason for the appointment, and how to continue the use of the discussion aid at future encounters. In the encounter in which the patient was able to discuss potential concerns of depression, the clinician noted that this added an additional 15–20 min to the encounter, whereas the actual discussion took less than 5 min. The perceived duration may have felt longer than the actual duration because of the heavy nature of the topic discussed. Past research in primary care patients with multimorbidity has shown that clinician comfort level with these types of difficult topics is low and that in practicing a traditional ‘additive-sequential model,’ where each problem is treated independently and prioritised, these issues may never get acknowledged.15 30 Therefore, the implementation of ICAN can provide an opportunity to train clinicians to address potentially difficult topics, manage their expectations of those discussions and learn how to successfully have those conversations. Specifically, this requires attention and clinician exposure in future ICAN trainings to the potentially uncomfortable and off-script conversations that may occur as a result of using the aid, as well as practice in having those conversations first in safe spaces, such as with peers and trainers, prior to real-life clinical encounters.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we successfully pilot tested the ICAN Discussion Aid in primary care encounters. This study illustrated that ICAN was perceived as feasible to implement in normal clinical practice, did not impact visit length, and impacted the conversation topics discussed in encounters. While patients perceived improved visit success with ICAN use, clinicians perceived worsened visit success. Clinical encounters that were noted as difficult to use ICAN point to additional ICAN training needs in future implementation and study settings. ICAN deserves further testing to determine if its implementation leads to better workload–capacity balance for patients living with chronic illness and if this translates to improved patient health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KRB was responsible for study design, overall study execution, analysis and the draft manuscript. CCD and AT conducted videographic analysis and provided critical revisions for the manuscript. MB and RG conducted statistical analysis, created tables and drafted the statistical sections of the manuscript. EB was responsible for the study coordination of the study and data collection procedures. PO assisted with data cleaning procedures, drafting of the manuscript and critical revisions to the manuscript. SVA served as clinical champion for the study and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. KS provided revisions to the manuscript and data visualisation. VMM assisted KRB with study design and oversight of the project.

Funding: This research was supported in part by an internal award from the Mayo Clinic Robert and Arlene Kogod Center for Aging.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board: 14-008621.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control Chronic diseases: the leading causes of death and disability in the United States, 2017. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/ [Accessed 17 May 2018].

- 2. Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National health interview survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E65 10.5888/pcd10.120203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eton DT, Ramalho de Oliveira D, Egginton JS, et al. . Building a measurement framework of burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2012;3:39–49. 10.2147/PROM.S34681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ridgeway JL, Egginton JS, Tiedje K, et al. . Factors that lessen the burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014;8:339–51. 10.2147/PPA.S58014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wyatt KD, Stuart LM, Brito JP, et al. . Out of context: clinical practice guidelines and patients with multiple chronic conditions: a systematic review. Med Care 2014;52 Suppl 3:S92–S100. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a51b3d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gallacher K, May CR, Montori VM, et al. . Understanding patients' experiences of treatment burden in chronic heart failure using normalization process theory. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:235–43. 10.1370/afm.1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gallacher K, Morrison D, Jani B, et al. . Uncovering treatment burden as a key concept for stroke care: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001473 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shippee ND, Shippee TP, Hess EP, et al. . An observational study of emergency department utilization among enrollees of Minnesota health care programs: financial and non-financial barriers have different associations. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:62 10.1186/1472-6963-14-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ 2009;339:b2803 10.1136/bmj.b2803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. May CR, Eton DT, Boehmer K, et al. . Rethinking the patient: using burden of treatment theory to understand the changing dynamics of illness. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:281 10.1186/1472-6963-14-281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bodenheimer T, Chen E, Bennett HD. Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: can the U.S. health care workforce do the job? Health Aff 2009;28:64–74. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Steiner JF. Seniors' self-reported multimorbidity captured biopsychosocial factors not incorporated into two other data-based morbidity measures. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e551:550–7. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cottrell E, Yardley S. Lived experiences of multimorbidity: an interpretative meta-synthesis of patients', general practitioners' and trainees' perceptions. Chronic Illn 2015;11:279–303. 10.1177/1742395315574764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Loeb DF, Binswanger IA, Candrian C, et al. . Primary care physician insights into a typology of the complex patient in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:451–5. 10.1370/afm.1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Brien R, Wyke S, Guthrie B, et al. . An ‘endless struggle’: a qualitative study of general practitioners’ and practice nurses’ experiences of managing multimorbidity in socio-economically deprived areas of Scotland. Chronic Illn 2011;7:45–59. 10.1177/1742395310382461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Safford MM. The complexity of complex patients. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1724–5. 10.1007/s11606-015-3472-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boehmer KR, Hargraves IG, Allen SV, et al. . Meaningful conversations in living with and treating chronic conditions: development of the ICAN discussion aid. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:514 10.1186/s12913-016-1742-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Breslin M, Mullan RJ, Montori VM. The design of a decision aid about diabetes medications for use during the consultation with patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:465–72. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, et al. . Cumulative complexity: a functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:1041–51. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. . Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ 2001;323:908–11. 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boehmer KR, Gionfriddo MR, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. . Patient capacity and constraints in the experience of chronic disease: a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:127 10.1186/s12875-016-0525-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tran V-T, Barnes C, Montori VM, et al. . Taxonomy of the burden of treatment: a multi-country web-based qualitative study of patients with chronic conditions. BMC Med 2015;13:115 10.1186/s12916-015-0356-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Academy of Medical Sciences Multimorbidity: a priority for global health research, 2018. Available: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/policy/policy-projects/multimorbidity [Accessed 6 Jun 2018].

- 24. Gill A, Kuluski K, Jaakkimainen L, et al. . "Where do we go from here?" Health system frustrations expressed by patients with multimorbidity, their caregivers and family physicians. Healthc Policy 2014;9:73–89. 10.12927/hcpol.2014.23811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eton DT, Ridgeway JL, Egginton JS, et al. . Finalizing a measurement framework for the burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2015;6:117–26. 10.2147/PROM.S78955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zulman DM, Kerr EA, Hofer TP, et al. . Patient-Provider concordance in the prioritization of health conditions among hypertensive diabetes patients. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:408–14. 10.1007/s11606-009-1232-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, et al. . How does communication heal? pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns 2009;74:295–301. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. . Decision AIDS for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;19 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mayo Clinic My life, my healthcare (ICAN) and statin choice used in a single visit, 2017. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a0H9RRGIFJg [Accessed 8 May 2019].

- 30. Bower P, Macdonald W, Harkness E, et al. . Multimorbidity, service organization and clinical decision making in primary care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract 2011;28:579–87. 10.1093/fampra/cmr018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029105supp001.pdf (115.4KB, pdf)