Abstract

Background

Robust data regarding genotype–phenotype correlations in left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC) are lacking.

Methods

About 72 cardiomyopathy‐related genes were comprehensively screened in a cohort of LVNC patients using targeted sequencing. Baseline and follow‐up data were collected. The primary endpoint was a composite of death and heart transplantation.

Results

A total of 83 unrelated adult patients were included in analyses. Following stringent classification according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines, 36 pathogenic variants of 14 genes were detected in 32 patients. Among them, 12 patients carried at least one nonsarcomere variant (NSV). At baseline, NSV carriers had a higher frequency of atrial fibrillation, but lower left ventricular ejection fraction, than did noncarriers. During a median follow‐up of 4.2 years, NSV carriers experienced a higher rate of the primary endpoint compared with noncarriers. There was no significant difference in the rate between carriers of sarcomere variant (SV) and noncarriers, as well as between carriers of SV and NSV. The presence of NSV was associated with an increased risk of the primary endpoint independent of age, sex, and cardiac function (hazard ratio: 3.61, 95% confidence interval: 1.42–9.19, p = .002).

Conclusion

NSV may act as a genetic modifier and worsen the clinical phenotype in patients with LVNC.

Keywords: genotype, left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy, prognosis

1. INTRODUCTION

Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC), which is characterized by abnormal trabeculations in the left ventricle, is present in 3%‒4% of patients with heart failure.(Kovacevic‐Preradovic et al., 2009; Patrianakos, Parthenakis, Nyktari, & Vardas, 2008) Clinical presentations of adult patients with LVNC are highly heterogeneous, varying from no apparent symptoms to serious complications, such as heart failure, arrhythmia, or thromboembolism.(Finsterer, Stollberger, & Towbin, 2017) Therefore, identifying high‐risk patients and providing them with proper treatment to improve prognosis are important.

Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy was classified as a genetic cardiomyopathy by the American Heart Association.(Maron et al., 2006) LVNC has been reported in association with >40 genes,(Finsterer et al., 2017) which can be broadly divided into sarcomere and nonsarcomere genes. Recent studies have shown that sarcomere variants (SV) account for most of the genetic defects in LVNC, with MYH7(OMIM 160760), MYBPC3 (OMIM 600958), and TTN (OMIM 188840) as the most prevalent genes.(Sedaghat‐Hamedani et al., 2017; van Waning et al., 2018).

A predictable association between genotype and phenotype is needed to use genetic testing for risk assessment. Most previous studies attempted to relate SV with disease expression in LVNC but yielded disappointing results.(Probst et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2015) However, whether there is a correlation between nonsarcomere variants (NSVs) and clinical outcomes remains unknown. To address this issue, we conducted the present study in a Chinese cohort of adult patients with LVNC.

2. METHODS

2.1. Ethical compliance

The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Study design and participants

Data were obtained from a cohort study, which enrolled 100 unrelated patients with LVNC at Fuwai Hospital between April 2004 and May 2016. Patients enrollment, genetic sequencing, variant classification, and follow‐up have been described in a previous study.(Li et al., 2018) Briefly, the diagnosis of LVNC was based on echocardiographic or cardiac magnetic resonance findings according to Jenni et al or Petersen et al criteria.(Jenni, Oechslin, Schneider, Attenhofer Jost, & Kaufmann, 2001; Petersen et al., 2005) Patients were eligible if they had LVNC and were willing to receive genetic testing and follow‐up. Since there are significant differences in genetic predisposition between child and adult patients (van Waning et al., 2018), only adult patients were included in the current analyses. Outcome data were obtained through a telephone interview or clinic visit. The last follow‐up was performed in April 2018.

2.3. Targeted sequencing

After informed consent was acquired, peripheral venous blood was collected for genomic DNA extraction. The coding exons and their adjacent 10‐bp intronic sequences of 72 cardiomyopathy‐related genes were comprehensively screened using targeted resequencing. Details about the genes being tested are described in supplementary material. The mean depth of all samples was more than 400×, with coverage of more than 99.7%. Variants were described according to the guidelines for mutation nomenclature of the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.hgvs.org/). Variants were excluded if their minor allele frequency was ≥0.05% among East Asians in the Genome Aggregation Database.(Lek et al., 2016) The pathogenicity of detected variants was determined in accordance with the recommendations of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology, and was classified as “pathogenic,” “likely pathogenic,” “uncertain significance,” “likely benign,” or “benign.”(Richards et al., 2015) In the current analysis, variants that were classified as “pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic” were considered to be pathogenic and divided into SV or NSV. Accordingly, patients were grouped into carriers of SV, carriers of NSV, or noncarriers. Sanger sequencing was used to validate the presence of pathogenic variants.

2.4. Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was a composite of death and heart transplantation (HT). The secondary endpoints included all‐cause death, HT, and cardiovascular death. Cardiovascular death included sudden cardiac death (SCD), heart failure (HF)‐related death, and death from other cardiovascular causes. SCD was defined as witnessed sudden death with or without documented ventricular fibrillation, death within 1 hr of new symptoms, or nocturnal deaths with no antecedent history of worsening symptoms. HF‐related death was defined as death preceded by symptoms of HF lasting >1 hr.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range) and categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentage. Analysis of variance was performed for comparison of continuous variables and Pearson chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test was performed for comparison of category variables. Univariable or multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were performed to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) to estimate the effect of pathogenic variants on phenotypes. Survival curves were constructed in accordance with the Kaplan–Meier method, and were compared using the log‐rank test. Factors that were included in the multivariate models for the outcomes were age, sex, and New York Heart Association functional class III/IV at baseline. Differences were considered significant if the two‐sided p‐value was <.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 22.0 software (IBM Corp.).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population and genetic findings

A total of 83 unrelated adult patients were included in the current analyses. Among them, 32 (38.6%) patients had 36 pathogenic variants in 14 genes, including 20 carriers of SV and 12 carriers of NSV (Tables 1 and S1). TTN, MYH7, and MYBPC3 were the most commonly involved sarcomere genes, while DSP (OMIM 125647) and DMD (OMIM 300377) were the most frequently mutated nonsarcomere genes.

Table 1.

Demographic, genetic, and clinical findings in patients with pathogenic variant of nonsarcomere gene

| Patient ID | Sex | Age at enrollment | Variant | Family history | Complicating cardiomyopathy/myopathy | NYHA class at baseline | Arrythmia at baseline | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | Female | 44 |

DSC2 c.C835T; TNNT2 c.G305A |

Sister: HCM | HCM | III | AF | |

| 17 | Female | 20 | LAMP2 c.325delT | Mother: LVNC | IV |

Ventricular preexcitation VT, AF, AVB |

HF‐related death | |

| 27 | Male | 53 | SCN5A c.G283A | No | IV | PVC | HF‐related death | |

| 38 | Male | 35 | DMD c.A3579 + 3T | No | DMD | IV | PVC, VT | |

| 43 | Male | 67 | DMD c.G7875A; MYBPC3 c.C1112T | No | III | PVC, VT | HF‐related death | |

| 66 | Male | 24 | DSP c.C1138T | No | DCM | III | VT | HT |

| 70 | Male | 45 | DSP c.G3901T | No | II | VT | ||

| 80 | Male | 43 | KCNE1 c.G200A | No | DCM | IV | PVC | HT |

| 99 | Male | 42 | DSP c.1_2insC | No | II | VT, AF | HF‐related death | |

| 105 | Female | 49 |

NNT c.1770dupC; MYH7 c.C2155T |

No | HCM | II | AF, LBBB | HF‐related death |

| 114 | Male | 61 |

DSP c.1_2insC; MYBPC3 c.2568delG |

No | III | AF, PVC, VT | HF‐related death | |

| 115 | Female | 53 | DSP c.1_2insC | No | II | VT |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; AVB, atrioventricular block; LBBB, left bundle branch block; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HF, heart failure; HT, heart transplantation; NYHA, New York Heart Association; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; PVC, premature ventricular contraction; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

3.2. Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2. SV carriers had a higher prevalence of a family history of cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, and atrioventricular block but a lower rate of hypertension, compared with noncarriers (p < .05 for all). NSV carriers had a higher frequency of atrial fibrillation, but lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), than did noncarriers (p < .05 for all). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between carriers of SV and NSV.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of nonsarcomere gene variants carriers and noncarriers

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 83) | SV carriers (n = 20) | NSV carriers (n = 12) | Noncarriers (n = 51) | p † |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment, year | 44.0 (34.0‒55.0) | 43.0 (35.5‒47.5) | 44.5 (36.8‒53.0) | 46.0 (30.0‒57.0) | NS |

| Age of onset, year | 40.0 (28.0‒51.0) | 37.5 (28.5‒43.5) | 44.0 (33.3‒50.8) | 42.0 (28.0‒52.0) | NS |

| Male, n (%) | 58 (69.9) | 14 (70.0) | 8 (66.7) | 36 (70.6) | NS |

| Family history of cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 11 (13.3) | 7 (35.0) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (3.9) | A;b |

| NYHA class III/IV, n (%) | 39 (47.0) | 9 (45.0) | 8 (66.7) | 22 (43.1) | NS |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 9 (10.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | 8 (15.7) | NS |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 (15.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (25.5) | A;b |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 7 (8.4) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (7.8) | NS |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 14 (16.9) | 4 (20.0) | 2 (16.7) | 8 (15.7) | NS |

| Other cardiomyopathies, n (%) | 21 (25.3) | 7 (35.0) | 4 (33.3) | 10 (19.6) | NS |

| Arrhythmia | |||||

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 15 (18.1) | 7 (35.0) | 4 (33.3) | 4 (7.8) | A;b;c |

| Premature ventricular contraction | 47 (56.6) | 10 (50.0) | 9 (75.0) | 28 (54.9) | NS |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 32 (38.6) | 9 (45.0) | 7 (58.3) | 16 (31.4) | NS |

| Atrioventricular block | 16 (19.3) | 8 (40.0) | 2 (16.7) | 6 (11.8) | A;b |

| LBBB | 20 (24.1) | 5 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) | 14 (27.5) | NS |

| RBBB | 3 (3.6) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | NS |

| Echocardiography | |||||

| LVEDD, mm | 62.0 (54.8‒70.0) | 64.5 (50.3‒71.3) | 65.5 (57.5‒70.0) | 61.0 (54.8‒70.0) | NS |

| LAD, mm | 41.5 (35.0‒48.0) | 42.5 (33.8‒50.8) | 44.5 (41.5‒49.8) | 40.0 (34.0‒46.5) | NS |

| LVEF, % | 38.5 (30.8‒52.3) | 33.1 (28.5‒47.0) | 29.0 (24.3‒43.0) | 40.0(33.0‒56.8) | c |

| Treatment | |||||

| Pacemaker, n (%) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.9) | NS |

| CRT, n (%) | 7 (8.4) | 2 (10.0) | 1 (8.3) | 5 (9.8) | NS |

| ICD, n (%) | 10 (12.0) | 4 (20.0) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (7.8) | NS |

Abbreviations: CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEDD, left ventricular end‐diastolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LBBB, left bundle branch block; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

A, significant difference between three groups; a, significant difference between the SV Carriers group and NSV Carriers group; b, significant difference between the SV Carriers group and Noncarriers group; c, significant difference between the NSV Carriers group and Noncarriers group; NS, not significant.

3.3. Clinical outcomes

During a median follow‐up of 4.2 years, 28 (33.7%) patients reached the primary endpoint, including 24 deaths and four HT (Table 3). Carriers of NSV experienced significantly higher rates of the primary endpoint, HT, and heart failure‐related death compared with noncarriers (p < .05 for all). There were no significant differences in rates of primary or secondary endpoints between carriers of SV and noncarriers, as well as between carriers of SV and NSV.

Table 3.

Incidence of primary and secondary endpoints

| All patients (n = 83) | SV carriers (n = 20) | NSV carriers (n = 12) | Noncarriers (n = 51) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | |||||

| Death and heart transplantation, n (%) | 28 (33.7) | 8 (40.0) | 8 (66.7) | 12 (23.5) | A; c |

| Secondary endpoints | |||||

| All‐cause death, n (%) | 24 (28.9) | 6 (30.0) | 6 (50.0) | 12 (23.5) | NS |

| Heart transplantation, n (%) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (10.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | A; c |

| Cardiovascular death, n (%) | 24 (28.9) | 6 (30.0) | 6 (50.0) | 12 (23.5) | NS |

| Sudden cardiac death, n (%) | 4 (4.8) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.9) | NS |

| Heart failure‐related death, n (%) | 19 (22.9) | 5 (25.0) | 6 (50.0) | 8 (15.7) | A; c |

p values: A, significant difference between three groups; c, significant difference between the NSV Carriers group and Non‐carriers group; NS, not significant.

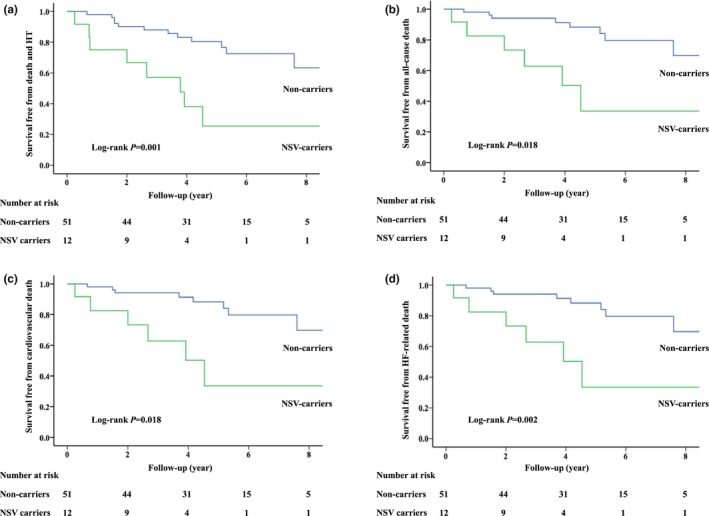

Univariable analyses showed that NSV was associated with an increased risk of death and HT compared with no variant (p = .002, Table 4 and Figure 1). Multivariable analysis showed that NSV was an independent risk factor of death and HT (HR: 3.61, 95% CI: 1.42‒9.19, p = .007, Table 4). For secondary endpoints, univariable analyses showed that NSV was associated with higher risks of all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and heart failure‐related death compared with no variant (Table 4 and Figure 1). After adjustment, NSV remained to be associated with increased risks of all‐cause death (HR: 2.88, 95% CI: 1.04‒7.96, p = .042), cardiovascular death (HR: 2.88, 95% CI: 1.04‒7.96, p = .042), and HF‐related death (HR: 3.97, 95% CI: 1.28‒12.24, p = .017, Table 4). There was no significant association between SV and primary or secondary endpoints (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable analyses of association between detected variants and clinical outcomes

| Univariable | Multivariable† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| SV versus no variant | ||||||

| Death and heart transplantation | 1.95 | 0.80‒4.79 | .143 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| All‐cause death | 1.46 | 0.55‒3.90 | .450 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Heart transplantation | NA‡ | NA‡ | NA‡ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Cardiovascular death | 1.46 | 0.55‒3.90 | .450 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Sudden cardiac death | 0.92 | 0.10‒8.89 | .945 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Heart failure‐related Death | 1.88 | 0.61‒5.75 | .271 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| NSV versus no variant | ||||||

| Death and heart transplantation | 4.05 | 1.64‒9.98 | .002 | 3.61 | 1.42‒9.19 | .007 |

| All‐cause death | 3.09 | 1.15‒8.30 | .025 | 2.88 | 1.04‒7.96 | .042 |

| Heart transplantation | NA‡ | NA‡ | NA‡ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Cardiovascular death | 3.09 | 1.15‒8.30 | .025 | 2.88 | 1.04‒7.96 | .042 |

| Sudden cardiac death | NA§ | NA§ | NA§ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Heart failure‐related Death | 4.80 | 1.65‒13.99 | .004 | 3.97 | 1.28‒12.24 | .017 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Items with p < .05 in univariable analyses were then included in the calculation of multivariable HR and 95% CI.

No heart transplantation occurred in noncarriers, so HR and 95% CI are not available.

No sudden cardiac death occurred in NSV carriers, so HR and 95% CI are not available.

Figure 1.

Survival curves free from death and heart transplantation (a), all‐cause death (b), cardiovascular death (c), and heart failure‐related death (d) in adult patients. Abbreviations: HF, heart failure; HT, heart transplantation; NSV, nonsarcomere variant

4. DISCUSSION

Among 83 adult patients with LVNC, we found that 12 (14.5%) carried at least 1 NSV, and DSP and DMD were the most commonly involved nonsarcomere genes. At baseline, NSV carriers had a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation and lower LVEF compared with noncarriers. During follow‐up, the presence of NSV was independently associated with an increased risk of a composite of death and HT, while the presence of SV was not significantly associated with clinical outcomes.

As a common genetic defect in LVNC, SV is identified in approximately 20%–30% of patients.(Probst et al., 2011; Sedaghat‐Hamedani et al., 2017; van Waning et al., 2018) There was no significant association between SV and clinical outcomes in previous studies (Table 5) and in our study. Aside from SV, NSV are also found in a minor proportion of patients with LVNC, including variants in cytoskeletal, ion channel, and mitochondrial genes.(Finsterer et al., 2017) In contrast to a recent study by van Waning et al. (Table 5), our study showed that NSV could increase the risk of adverse events in adult patients with LVNC. There were some differences between these studies that should be noted. Our study focused only on adult patients while in the study by van Waning et al, the multivariable analysis regarding NSV was performed among patients of all ages. Besides, the primary endpoint in van Waning et al study differed from ours, with thromboembolism and arrythmia events additionally being included. These differences might contribute to the contradictory results between two studies.

Table 5.

An overview of previous studies on the relationship between SV/NSV and phenotype in LVNC patients

| Study | Study population | Genetic testing | Prevalence | Relationship with phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarcomere variants | ||||

| Probst et al., 2011 | 63 European probands (adults and children) | 8 genes | 18/63 (29%) with mutated MYH7, MYBPC3, ACTC1, TNNT2, or TPM1 | No significant differences in average age, cardiac function, and heart failure or tachyarrhythmias at baseline or follow‐up between carriers and noncarriers |

| Tian et al., 2015 | 57 Chinese probands (adults and children) | 10 genes | 7/57 (12%) with mutated MYH7, ACTC1, TNNT2, or TPM1 | No significant differences in clinical characteristics at baseline and mortality during follow‐up between carriers and noncarriers |

| van Waning et al., 2018 | 327 European probands (adults and children) | 45 genes | 85/327 (26%) with mutated MYH7, MYBPC3, TTN, ACTC1, ACTN2, TNNC1, TNNT2, MYL2, or TPM1 | No significant differences in adverse events at baseline or follow‐up between carriers and noncarriers |

| Nonsarcomere variants | ||||

| van Waning et al., 2018 | 327 European probands (adults and children) | 45 genes | 19/327 (6%) with mutated DES, DSP, FKTN, HCN4, KCNQ1, LAMP2, LMNA, MIB1, NOTCH1, PLN, RYR2, SCN5A, or TAZ | No significant differences in adverse events at baseline or follow‐up between carriers and noncarriers |

In our previous study (Li et al., 2018), the presence of pathogenic variants (SV/NSV) was found to be associated with an increased risk of death and HT among adult patients with LVNC. Further analyses in the current study showed that the majority of this increased risk was accounted by the presence of NSV rather than SV. Therefore, patients with pathogenic variants, especially those with NSV, may have a high risk of adverse events and should be followed up closely.

Loss‐of‐function variants in SCN5A (OMIM 600163), which encodes the α‐subunit of the cardiac sodium channel, can cause dilated cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome, cardiac conduction defect, sick sinus syndrome, and atrial fibrillation.(Wilde & Amin, 2018) Although the relationship between SCN5A and LVNC remains to be established, the presence of SCN5A variant increases the risk of arrhythmia and HF in LVNC patients.(Shan et al., 2008) There is no association between KCNE1 (OMIM 176261) and changes in left ventricular morphology, but KCNE1 variant has an effect on rectifier K+ current and has been recognized as a cause for long QT syndrome.(Nishio et al., 2009) Therefore, variants in SCN5A and KCNE1 can lead to increased susceptibility to arrhythmia and result in an adverse prognosis.

DSP and DSC2 (OMIM 125645) encode desmosome proteins and are established disease genes for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy.(Corrado, Basso, & Judge, 2017) A truncating variant in DSP is also related to LVNC and severe early‐onset HF.(Williams et al., 2011) An association between DSC2 and LVNC has not been reported to date. Knockdown of DSC2 in zebrafish embryos can cause myocardial contractility defects,(Heuser et al., 2006) suggesting that DSC2 variants may be able to impair contractile function and eventually lead to HF.

Defects in DMD and NNT (OMIM 607878) have been associated with LVNC. DMD encodes the structural cytoskeletal protein dystrophin. Mutations in DMD result in Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy.(Kamdar & Garry, 2016) Patients with LVNC have an increased risk of mortality when complicated by neuromuscular disorders.(Stollberger et al., 2015; Stollberger, Blazek, Wegner, Winkler‐Dworak, & Finsterer, 2011) NNT encodes a mitochondrial protein. Suppression of Nnt in zebrafish causes early ventricular malformation and contractility defects,(Bainbridge et al., 2015) suggesting that a defect in NNT may contribute to susceptibility to HF.

LAMP2 (OMIM 309060) cardiomyopathy is a profound disease process that is characterized by progressive HF and severe arrhythmia, rapidly leading to cardiac death in young patients.(Maron et al., 2009) The clinical features of this disease include left ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation, and ventricular preexcitation. LVNC has also been reported as a phenotype of LAMP2 cardiomyopathy.(Van Der Starre et al., 2013) In our study, one female patient with the LAMP2 variant presented with LVNC, atrial fibrillation, and ventricular preexcitation, but without apparent ventricular hypertrophy, and died of progressive HF at a young age. These findings provide additional evidence for the adverse prognosis and clinical heterogeneity of LAMP2 cardiomyopathy.

Although most of these nonsarcomere genes have no clear relevance with LVNC, the presence of pathogenic variants in these genes was associated with serious manifestations in patients with LVNC in our study, including a lower LVEF and an increased risk of adverse outcomes. This finding suggests that NSV, at least some of them, may act as genetic modifiers and influence phenotypic expression, which could partially explain the remarkable heterogeneity in the clinical manifestation of LVNC. However, additional studies are required to replicate and further evaluate the potential effect of NSVs on LVNC.

There are some limitations that should be noted in this study. First, this was an observational study and all of the patients were recruited from a specialized center for cardiovascular diseases, which might have led to selection and measurement bias. Second, the sample size was relatively small, which might have limited the power of our findings. Third, despite the fact that more than 70 cardiomyopathy‐associated genes were comprehensively screened, some other nonsarcomere genes might also have an effect on the disease, which could not be evaluated.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting that the presence of NSV is associated with adverse outcomes in adult patients with LVNC. NSV, at least some of them, may act as genetic modifiers and influence the clinical phenotype. These findings may aid in risk stratification in patients with LVNC.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all the staff members for data collection, data entry, and monitoring for their contribution to the current study.

Li S, Zhang C, Liu N, Bai H, Hou C, Pu J. Clinical implications of sarcomere and nonsarcomere gene variants in patients with left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7:e874 10.1002/mgg3.874

Funding information

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81470460).

REFERENCES

- Bainbridge, M. N. , Davis, E. E. , Choi, W. Y. , Dickson, A. , Martinez, H. R. , Wang, M. , … Jefferies, J. L. (2015). Loss of function mutations in NNT Are associated with left ventricular noncompaction. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics, 8(4), 544–552. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrado, D. , Basso, C. , & Judge, D. P. (2017). Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research, 121(7), 784–802. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer, J. , Stollberger, C. , & Towbin, J. A. (2017). Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy: Cardiac, neuromuscular, and genetic factors. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 14(4), 224–237. 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser, A. , Plovie, E. R. , Ellinor, P. T. , Grossmann, K. S. , Shin, J. T. , Wichter, T. , … Gerull, B. (2006). Mutant desmocollin‐2 causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. American Journal of Human Genetics, 79(6), 1081–1088. 10.1086/509044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenni, R. , Oechslin, E. , Schneider, J. , Attenhofer Jost, C. , & Kaufmann, P. A. (2001). Echocardiographic and pathoanatomical characteristics of isolated left ventricular non‐compaction: A step towards classification as a distinct cardiomyopathy. Heart, 86(6), 666–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamdar, F. , & Garry, D. J. (2016). Dystrophin‐Deficient Cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 67(21), 2533–2546. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacevic‐Preradovic, T. , Jenni, R. , Oechslin, E. N. , Noll, G. , Seifert, B. , & Attenhofer Jost, C. H. (2009). Isolated left ventricular noncompaction as a cause for heart failure and heart transplantation: A single center experience. Cardiology, 112(2), 158–164. 10.1159/000147899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek, M. , Karczewski, K. J. , Minikel, E. V. , Samocha, K. E. , Banks, E. , Fennell, T. , … Exome Aggregation, C. (2016). Analysis of protein‐coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature, 536(7616), 285–291. 10.1038/nature19057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Zhang, C. , Liu, N. , Bai, H. , Hou, C. , Wang, J. , … Pu, J. (2018). Genotype‐positive status is associated with poor prognoses in patients with left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American Heart Association, 7(20), e009910 10.1161/JAHA.118.009910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron, B. J. , Roberts, W. C. , Arad, M. , Haas, T. S. , Spirito, P. , Wright, G. B. , … Seidman, C. E. (2009). Clinical outcome and phenotypic expression in LAMP2 cardiomyopathy. JAMA, 301(12), 1253–1259. 10.1001/jama.2009.371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron, B. J. , Towbin, J. A. , Thiene, G. , Antzelevitch, C. , Corrado, D. , Arnett, D. , … Council on Epidemiology and Prevention . (2006). Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: An American heart association scientific statement from the council on clinical cardiology, heart failure and transplantation committee; quality of care and outcomes research and functional genomics and translational biology interdisciplinary working groups; and council on epidemiology and prevention. Circulation, 113(14), 1807–1816. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio, Y. , Makiyama, T. , Itoh, H. , Sakaguchi, T. , Ohno, S. , Gong, Y. Z. , … Horie, M. (2009). D85N, a KCNE1 polymorphism, is a disease‐causing gene variant in long QT syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 54(9), 812–819. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrianakos, A. P. , Parthenakis, F. I. , Nyktari, E. G. , & Vardas, P. E. (2008). Noncompaction myocardium imaging with multiple echocardiographic modalities. Echocardiography, 25(8), 898–900. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2008.00708.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, S. E. , Selvanayagam, J. B. , Wiesmann, F. , Robson, M. D. , Francis, J. M. , Anderson, R. H. , … Neubauer, S. (2005). Left ventricular non‐compaction: Insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 46(1), 101–105. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst, S. , Oechslin, E. , Schuler, P. , Greutmann, M. , Boye, P. , Knirsch, W. , … Klaassen, S. (2011). Sarcomere gene mutations in isolated left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy do not predict clinical phenotype. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics, 4(4), 367–374. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.959270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, S. , Aziz, N. , Bale, S. , Bick, D. , Das, S. , Gastier‐Foster, J. , … Committee, A. L. Q. A. (2015). Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine, 17(5), 405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedaghat‐Hamedani, F. , Haas, J. , Zhu, F. , Geier, C. , Kayvanpour, E. , Liss, M. , … Meder, B. (2017). Clinical genetics and outcome of left ventricular non‐compaction cardiomyopathy. European Heart Journal, 38(46), 3449–3460. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L. , Makita, N. , Xing, Y. , Watanabe, S. , Futatani, T. , Ye, F. , … Towbin, J. A. (2008). SCN5A variants in Japanese patients with left ventricular noncompaction and arrhythmia. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 93(4), 468–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollberger, C. , Blazek, G. , Gessner, M. , Bichler, K. , Wegner, C. , & Finsterer, J. (2015). Neuromuscular comorbidity, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation as prognostic factors in left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. Herz, 40(6), 906–911. 10.1007/s00059-015-4310-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollberger, C. , Blazek, G. , Wegner, C. , Winkler‐Dworak, M. , & Finsterer, J. (2011). Neuromuscular and cardiac comorbidity determines survival in 140 patients with left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. International Journal of Cardiology, 150(1), 71–74. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, T. , Wang, J. , Wang, H. , Sun, K. , Wang, Y. , Jia, L. , … Song, L. (2015). A low prevalence of sarcomeric gene variants in a Chinese cohort with left ventricular non‐compaction. Heart and Vessels, 30(2), 258–264. 10.1007/s00380-014-0503-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Starre, P. , Deuse, T. , Pritts, C. , Brun, C. , Vogel, H. , & Oyer, P. (2013). Late profound muscle weakness following heart transplantation due to Danon disease. Muscle and Nerve, 47(1), 135–137. 10.1002/mus.23517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Waning, J. I. , Caliskan, K. , Hoedemaekers, Y. M. , van Spaendonck‐Zwarts, K. Y. , Baas, A. F. , Boekholdt, S. M. , … Majoor‐Krakauer, D. (2018). Genetics, clinical features, and long‐term outcome of noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 71(7), 711–722. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde, A. A. M. , & Amin, A. S. (2018). Clinical spectrum of SCN5A mutations: Long QT syndrome, brugada syndrome, and cardiomyopathy. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology, 4(5), 569–579. 10.1016/j.jacep.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T. , Machann, W. , Kuhler, L. , Hamm, H. , Muller‐Hocker, J. , Zimmer, M. , … Schonberger, J. (2011). Novel desmoplakin mutation: Juvenile biventricular cardiomyopathy with left ventricular non‐compaction and acantholytic palmoplantar keratoderma. Clinical Research in Cardiology, 100(12), 1087–1093. 10.1007/s00392-011-0345-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials