Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between heart rate (HR) and optimal reconstruction phase in prospectively electrocardiogram (ECG)-triggered coronary CT angiography (CCTA) performed on a newly introduced 256-slice multidetector CT (MDCT).

Methods:

All the cases were selected retrospectively from the patients scheduled for CCTA in our department between January and April 2017. The scanner selected the optimal exposure phase based on 10 s ECG recordings. To ensure the success of CCTA, the operator also checked patient's age, breathing control, emotional status and past medical history to decide whether the automatically selected scan phase needs manual adjustment or not. Images were reconstructed in 1% steps of the R–R interval to determine the cardiac phase with least coronary motion. If CCTA images showed moderate motion blurring or discontinuity in the course of coronary segments, a cardiac motion correction algorithm was applied to the reconstructed images. Subjective diagnostic image quality was evaluated with 4-point grading scale.

Results:

A total of 87 consecutive CCTA examinations were investigated in this study. Diastolic reconstruction was applied to all vessel segments in patients with HR <63 bpm, where 36.5 and 77.8% of vessel segments were reconstructed with the use of motion correction in HR ≤57 and 58–62 bpm, respectively. As for patients with HR ≥63 bpm, 89.3 and 71.7% of vessel segments were reconstructed in diastole in HR 63–67 and ≥68 bpm, respectively, while 81 and 100% of vessel segments were reconstructed with the use of motion correction in the same HR groups.

Conclusion:

Based on our results, a HR less than 67 bpm can be used to identify appropriate patients for diastolic reconstruction. Although the motion correction algorithm is an effective approach to reduce the impact of cardiac motion in CCTA, HR control is still important to optimize the image quality of CCTA. The relationship between HR and optimal reconstruction phase established in this study could be further used to tailor the ECG pulsing window for dose reduction in patients undergoing CCTA performed on the 256-slice MDCT.

Advances in knowledge:

The HR thresholds to identify patients who are the best suitable candidates for diastolic or systolic reconstruction are scanner specific. This study investigated the relationship between HR and optimal reconstruction phase in prospectively ECG-triggered CCTA for a newly introduced 256-slice MDCT. Once the relationship is established, it could be used to tailor the ECG pulsing window for radiation dose reduction.

Introduction

Coronary CT angiography (CCTA) is an important imaging tool in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, which can be performed with either retrospective ECG gating or prospective ECG triggering. In retrospective acquisitions, radiation is emitted throughout the cardiac cycle, so retrospective gating is useful in patients who do not have a stable heart rate (HR) and thus have an unpredictable interval of minimum cardiac motion. However, it is generally known that retrospective ECG gating leads to higher radiation exposure than prospective ECG triggering.1,2 Prospective ECG triggering is a dose-efficient CCTA acquisition technique, but it provides less cardiac phases for interpretation. Hence, the ECG pulsing window should be determined appropriately to reduce the impact of cardiac motion artifacts on the image quality of CCTA.3–5 Cardiac motion is one of the most common sources of artifacts in CCTA.6–8 An elevated HR is associated with faster cardiac motion, so increasing HR would cause blurring of CCTA images. Temporal resolution is a critical component to obtain CCTA images that are free from cardiac motion artifacts. Reducing motion artifacts can also be achieved by selecting the cardiac phase with least motion. Mid-diastole (during diastasis) is relatively quiescent compared with other phases in patients with low and stable HR, while the most quiescent phase occurs in systole at high HR.9–11 CCTA performed in these cardiac phases demonstrates least motion artifacts, so they are considered to be the optimal reconstruction window of CCTA.12–14 Husmann et al15 and Buechel et al16 have reported that a HR below 63 bpm favors diagnostic image quality in prospectively ECG-triggered CCTA reconstructed at 75% of the R–R interval. The HR thresholds to identify patients who are the best suitable candidates for diastolic or systolic reconstruction are scanner specific because they depend on the temporal resolution of CT scanner. A 256-slice MDCT has been recently installed in Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, which enables tube rotation time of 0.275 s and 16 cm axial coverage. Besides hardware improvements, this 256-slice MDCT is equipped with a motion correction algorithm to compensate for the cardiac motion-related blurring. We hypothesized that the HR threshold for the 256-slice MDCT should be different from 63 bpm because of the advancements in hardware and software technologies. In order to determine the optimal value, this study investigated the relationship between HR and optimal reconstruction phase for prospectively ECG-triggered CCTA performed on a 256-slice MDCT. Korosoglou et al have reported that retrospectively triggered protocols are more frequently used in patients with irregular heart rhythm, resulting in higher radiation exposure and possibly contrast agent administration.17 Since examination of retrospective ECG gating is beyond the scope of this work, patients with irregular heart rhythm were excluded.

Methods

I.Retrospective CCTA study

All the cases were selected retrospectively from the patients scheduled for CCTA in our department between January and April 2017. Approval was gained from the Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee to obtain access to patient data. A total of 91 persons were schedule for CCTA examination during the study period; two were excluded because of iodine allergy and two were excluded because of severely impaired renal function (eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2). Patients with HR >70 bpm were given 10–30 mg of oral propranolol (Propranolol Tab, Standard Chem & Pharm Co., LTD, Taiwan) one hour before examination. All patients received 0.6 mg of sublingual nitroglycerin (Nitrostat, Pfizer Pharma, Vega Baja, Puerto Rico) 2 min prior to the scan unless contraindicated.

CCTA acquisition

CCTA acquisition was performed using prospectively ECG-triggered axial scanning on a 256-row detector CT scanner (Revolution CT, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). Non-ionic contrast agent (Optiray 350, loversol injection 74%, Liebel-Flarshein Canada Inc., Canada) was administered intravenously in dose of 0.8 ml/kg body weight at a flow rate of 3.5–6.0 ml s−1, followed by a 30 ml saline chaser at 3.0–5.0 ml s−1. CCTA scans were triggered automatically by a delay of 5.9 s when contrast enhancement within the descending aorta reached a threshold level of 80 Hounsfield unit (HU). The scan field of view (SFOV) and z-axis coverage were chosen according to the heart size. The tube voltage was adjusted manually based on patient attenuation, while the tube current was determined automatically by the automatic exposure control (AEC) system (SmartmA, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) to achieve a noise index (NI) of 22 HU.

ECG pulsing window

The scanner used 10 s ECG trace information within the last test breath-hold to determine target phases for reconstruction, i.e. the most quiescent phase of cardiac cycle, which should be during end-diastole at low HR and end-systole at high HR.18 With the scanner default settings, ECG pulsing window was set at 70–85% of the R–R interval for patients with HR≤65 bpm. As for patients with 65 bpm <HR ≤85 bpm, full tube current was applied at 40–55% + 70–85% of the R–R interval. For patients with HR >85 bpm or HR variability >8 bpm, ECG pulsing window was set at 20–90% of the R-R interval. To ensure the success of CCTA, the operator also checked patient's age (>70 years old), breathing control (unable to hold breath for 10 sec), emotional status (feeling tense, nervous or unable to relax) and past medical history (asthma, obstructive pulmonary disease, decompensated heart failure, vasospastic or vaso-occlusive disease) to determine the needs for a ECG pulsing window wider than the automatically selected scan phase.

CCTA optimal reconstruction

After scanning, images were reconstructed by using 50% FBP and ASiR-V blending, a slice thickness of 0.625 mm, and 512 × 512 matrix size at 1% steps of the R-R interval to determine the optimal phase of the coronary arteries with least coronary motion. Axial images, volume rendering images and curved planar reformation images were comprehensively evaluated. If CCTA images reconstructed at the optimal phase showed moderate motion blurring or discontinuity in the course of coronary segments, a cardiac motion correction algorithm (SnapShot Freeze, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) was applied to reconstructed images. In our routine practice, the optimal reconstruction phase and the use of motion correction were determined by two experienced cardiovascular radiologists in consensus. To investigate the impact of patient characteristics on the selection of data acquisition and reconstruction schemes, patients were divided into four groups based on the optimal reconstruction phase and whether the motion correction function was used or not: (1) diastolic reconstruction without the use of motion correction was applied to all vessel segments in an individual patient (phaseD); (2) diastolic reconstruction with the use of motion correction was applied to all vessel segments in an individual patient (phaseD:SSF); (3) systolic reconstruction with the use of motion correction was applied to some parts of the coronary arteries because the image quality of CCTA reconstructed in diastolic phase with the use of motion correction was not sufficient for all vessel segments in an individual patient (phaseD +S:SSF); (4) systolic reconstruction with the use of motion correction was applied to all vessel segments in an individual patient (phaseS:SSF).

Subjective image quality assessment

Subjective image quality was rated using 4-point grading scale for quantifying the impact of cardiac motion on every coronary artery segment with at least 1.0 mm diameter: 1 = excellent, no motion artifacts, clear delineation of the segment; 2 = good, minor artifacts, mild blurring of the segment; 3 = adequate, moderate artifacts, moderate blurring without structure discontinuity; 4 = not evaluative, doubling or discontinuity in the course of the segment preventing evaluation or vessel structures not differentiable. Coronary arteries was classified according to the American Heart Association15-segment model.19 The right coronary artery (RCA), the left main and left anterior descending (LAD) artery, and the left circumflex (LCX) artery were defined to include segment 1–4, segment 5–10, and segment 11–15, respectively. Two experienced cardiovascular radiologists independently rated the best quality CCTA images of enrolled patients in random order to reduce the likelihood of recall bias.

Radiation dose

The volume CT dose index (CTDIvol) and dose–length product (DLP) displayed on the scanner console were recorded after CCTA scans. Effective dose was calculated as the product of DLP times a conversion coefficient for chest (k = 0.014 mSv × [mGy ×cm]−1).20

Data analysis

The comparison among patients belonging to phaseD, phaseD:SSF, phaseD + S:SSF and phaseS:SSF was assessed by using one-way repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey's post hoc test for normally distributed variables [age, body mass index (BMI), HR, HR variability, tube voltage, tube current, exposure time, CTDIvol, scan length, effective dose] and Friedman test for non-parametric variables (beta-blocker, ECG pulsing window, SFOV, detector coverage). As for the subjective image quality, the interobserver agreement was analyzed with Cohen κ coefficient (κ < 0.40: poor agreement; 0.40 ≤ κ < 0.75: good agreement; and κ ≥ 0.75: excellent agreement). It has been reported that the HR threshold of diastolic reconstruction is 62 bpm for a 64-slice MDCT with gantry rotation time of 0.35 s and 4 cm axial coverage.15,16 Meanwhile, all CCTA images of our enrolled patients with HR ≥68 bpm were reconstructed with the use of motion correction. Hence, each patient group categorized according to reconstruction techniques was further divided into 4 h groups: (1) HR ≤57 bpm; (2) 58 bpm <HR ≤62 bpm; (3) 63 bpm <HR ≤67 bpm; (4) HR ≥68 bpm. A statistically significant difference was defined as a two-sided p value < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v. 18 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

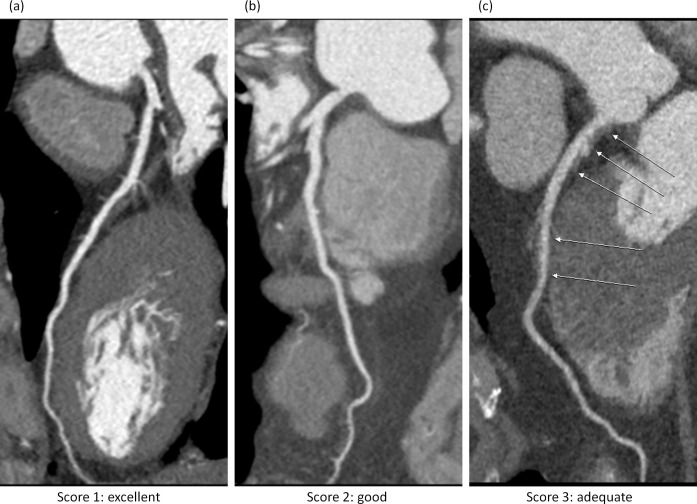

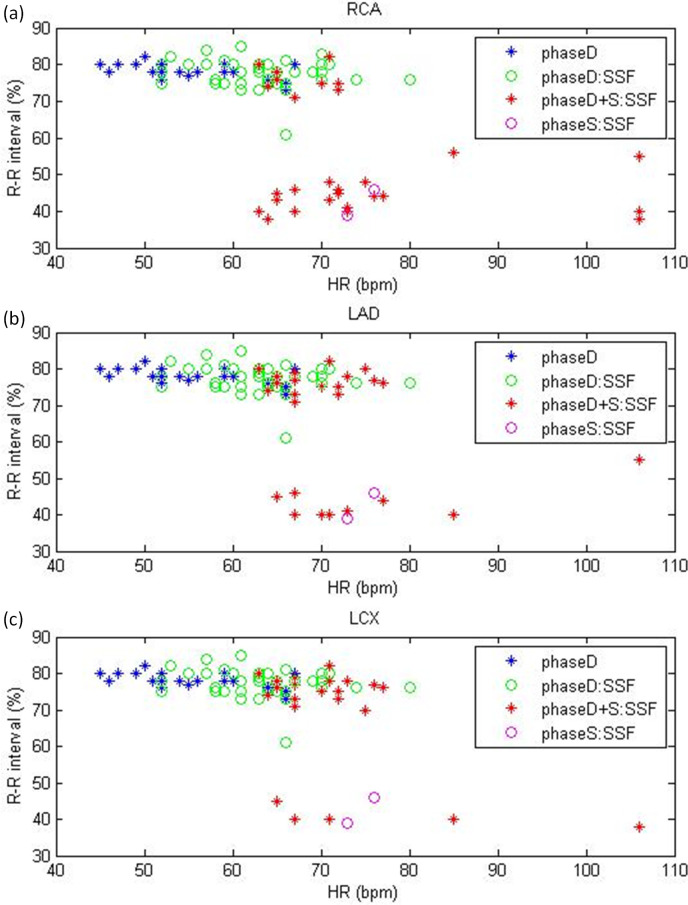

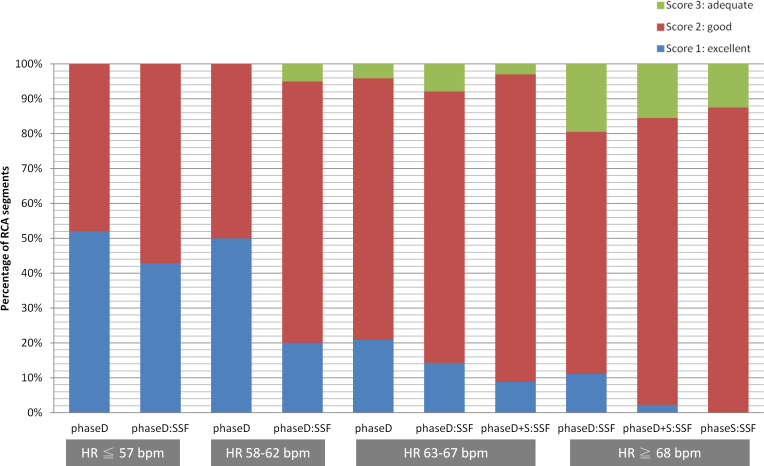

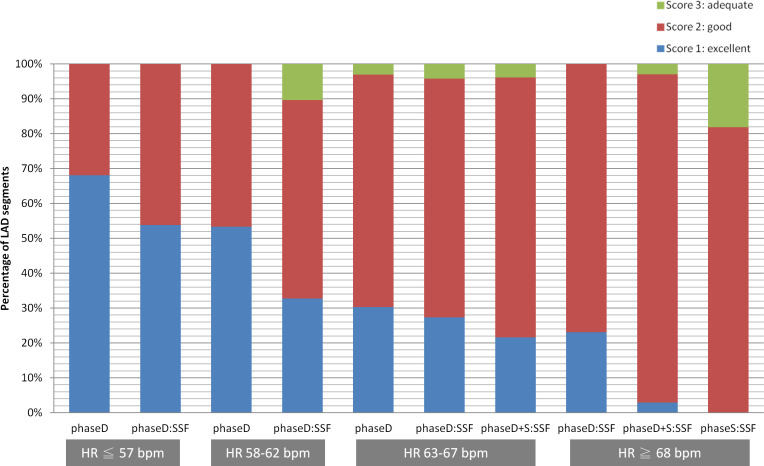

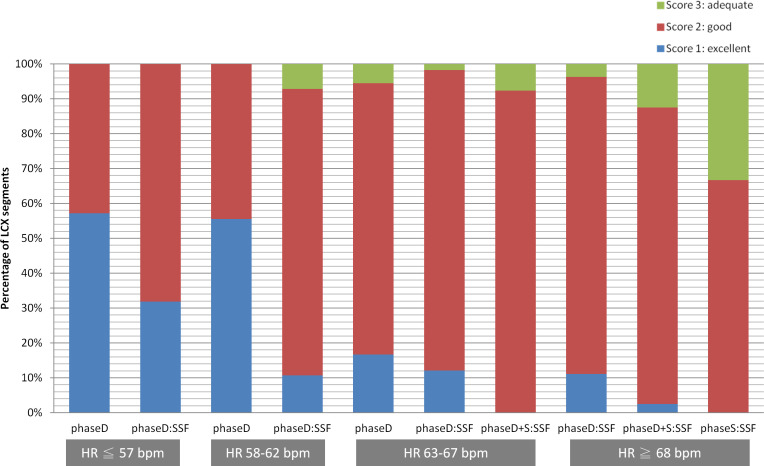

A total of 87 consecutive CCTA examinations for adult patients (26 females, 61 males; age range 31–82 years; HR range 45–106 bpm; BMI range 18.21–38.19 kg/m2) undergoing prospectively ECG-triggered axial scans were investigated in this study. Patients were referred because of chest pain (16%), dyspnea (7%), positive stress test (10%), elevated cardiovascular risk (3%), coronary stent (3%), physical exam (50%), and follow-up (11%). Examples of the rating scores were shown in Figure 1. For our enrolled patients, an ECG pulsing window wider than the automatically selected scan phase was applied in 30 patients because of age (2), breathing control (10), emotional status (13), past medical history (5). Detailed patient characteristics, scan parameters and radiation dose for patients categorized as phaseD, phaseD:SSF, phaseD + S:SSF, phaseS:SSF are summarized in Table 1. Significant differences among four groups were found in patients receiving beta-blocker, BMI, HR, and pulsing window. Figure 2 shows the optimal reconstruction phase for RCA, LAD and LCX. There were 1098 coronary artery segments in 87 patients, including 338 RCA segments, 491 LAD segments, and 269 LCX segments. Diastolic and systolic reconstructions were used in 79.59 and 20.41% of RCA segments. The corresponding results were 92.26 and 7.74% for LAD segments, and 92.94 and 7.06% for LCX segments. With regards to subjective scoring of motion artifacts, inter observer agreement was excellent (κ = 0.90; 95% confidence interval: 0.83–0.97). All disagreements were discussed and a consensus was found. Table 2 summarizes the percentage of vessel segments rated as diagnostically evaluable (motion scores 1–3) or not interpretable (motion score 4) for patients categorized according to reconstruction techniques and HR. All segments showed acceptable diagnostic information (i.e. motion scores ≤ 3). The percentages of segments rated as score 1, 2 and 3 were 49.05%, 49.81%, 1.14% for patients categorized as phaseD (263 segments), respectively. The corresponding results were 23.99%, 70.88%, 5.13% in phaseD:SSF (546 segments), 6.82%, 85.98%, 7.20% in phaseD + S:SSF (264 segments), 0.00%, 80.00%, 20.00% in phaseS:SSF (25 segments). For patients with HR ≤57 bpm (241 segments), 63.1 and 36.9% of segments belong to phaseD and phaseD:SSF, respectively, while the corresponding results were 22.2 and 77.8% for patients with HR 58–62 bpm (162 segments). With regards to patients with HR 63–67 bpm (402 segments), 18.7%, 53.7 and 27.6% of vessel segments belong to phaseD, phaseD:SSF and phaseD + S:SSF, respectively. As for patients with HR ≥68 bpm (293 segments), the motion correction algorithm was applied to all vessel segments, where 39.3%, 52.2% and 8.5% of vessel segments belong to phaseD:SSF, phaseD + S:SSF and phaseS:SSF, respectively. Figure 3 demonstrates the percentage of RCA segments (segment 1–4) rated as score 1, 2 and 3 for patients categorized into 10 subgroups. The corresponding results for LAD segments (segment 5–10) and LCX segments (segment 11–15) were shown in Figures 4 and 5, respectively.

Figure 1. .

Curved multiplanar reformations of LCX rated as subjective score = 1, 2 and 3 (left to right). (a) HR = 53 bpm, BMI = 20.2 kg/m2, phaseD; (b) HR = 69 bpm, BMI = 25.6 kg/m2, phaseD:SSF; (c) HR = 73 bpm, BMI = 39.1 kg/m2, phaseS:SSF. BMI, body mass index; HR, heart rate; LCX, left circumflex.

Table 1. .

Comparison of patient characteristics, scan parameters and radiation dose among four patient groups

| phaseD | phaseD:SSF | phaseD +S:SSF | phaseS:SSF | p value | ||

| Patients receiving beta-blockers/total patients | 1/21 | 8/43 | 6/21 | 1/2 | 0.049* | |

| Age | 58.95 ± 7.24 | 58.79 ± 12.07 | 58.81 ± 7.71 | 57.00 ± 7.07 | 0.995 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.55 ± 3.65 | 24.86 ± 3.02 | 24.37 ± 2.90 | 29.22 ± 2.67 | 0.035* | |

| HR (bpm) | 56.00 ± 7.01 | 63.49 ± 6.02 | 71.95 ± 9.42 | 74.50 ± 2.12 | <0.001* | |

| HR variability (bpm) | 5.57 ± 3.57 | 6.19 ± 4.57 | 4.86 ± 3.48 | 3.00 ± 2.83 | 0.080 | |

| Pulsing window | 70–85% | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.031* |

| 40–55% + 70–85% | 13 | 37 | 19 | 2 | ||

| 20–90% | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Tube voltage (kVp) | 118.10 ± 8.73 | 116.74 ± 9.69 | 114.29 ± 9.26 | 120.00 ± 0.00 | 0.551 | |

| Tube current (mA) | 670.00 ± 81.28 | 660.56 ± 82.11 | 677.57 ± 71.71 | 724.50 ± 7.78 | 0.053 | |

| Exposure time (s) | 0.70 ± 0.14 | 0.72 ± 0.10 | 0.75 ± 0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.01 | 0.462 | |

| SFOV | Small | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.644 |

| Medium | 17 | 39 | 19 | 2 | ||

| Large | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Detector coverage | 12 cm | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.759 |

| 14 cm | 9 | 14 | 12 | 1 | ||

| 16 cm | 12 | 27 | 9 | 1 | ||

| CTDIvol (mGy) | 22.65 ± 7.69 | 22.49 ± 6.96 | 21.64 ± 4.11 | 23.47 ± 0.41 | 0.946 | |

| Scan length (mm) | 150.80 ± 10.14 | 150.54 ± 10.96 | 147.95 ± 10.14 | 149.38 ± 14.14 | 0.796 | |

| Effective dose (mSv) | 4.80 ± 1.70 | 4.78 ± 1.46 | 4.50 ± 0.94 | 4.93 ± 0.55 | 0.873 | |

BMI, body mass index; CTDIvol, volume CT dose index; HR, heart rate; SFOV, scan field of view.

The difference among four patient groups was statistically significant.

Figure 2. .

Optimal reconstruction phase for (a) RCA, (b) LAD, (c) LCX as a function of HR on a per segment basis. HR, heart rate; LAD, left anterior descending; LCX, left circumflex; RCA, rightcoronary artery.

Table 2. .

Percentage of vessel segment scoring for patients categorized into phaseD, phaseD:SSF, phaseD + S:SSF, phaseS:SSF with HR ≦57, 58–62, 63–67, ≧68 bpm

| HR ≦57 bpm |

HR 58–62 bpm |

HR 63–67 bpm |

HR ≧68 bpm |

||

| phaseD | Score 1a | 60.53% (92/152) | 52.78% (19/36) | 24.00% (18/75) | --- |

| Score 2b | 39.47% (60/152) | 47.22% (17/36) | 72.00% (54/75) | --- | |

| Score 3c | 0.00% (0/152) | 0.00% (0/36) | 4.00% (3/75) | --- | |

| Score 4d | 0.00% (0/152) | 0.00% (0/36) | 0.00% (0/75) | --- | |

| phaseD: SSF | Score 1 | 44.94% (40/89) | 23.81% (30/126) | 19.44% (42/216) | 16.52% (19/115) |

| Score 2 | 55.06% (49/89) | 68.25% (86/126) | 75.93% (164/216) | 76.52% (88/115) | |

| Score 3 | 0.00% (0/89) | 7.94% (10/126) | 4.63% (10/216) | 6.96% (8/115) | |

| Score 4 | 0.00% (0/89) | 0.00% (0/126) | 0.00% (0/216) | 0.00% (0/115) | |

| phaseD +S: SSF | Score 1 | --- | --- | 12.61% (14/111) | 2.61% (4/153) |

| Score 2 | --- | --- | 82.88% (92/111) | 88.24% (135/153) | |

| Score 3 | --- | --- | 4.50% (5/111) | 9.15% (14/153) | |

| Score 4 | --- | --- | 0.00% (0/111) | 0.00% (0/153) | |

| phaseS: SSF | Score 1 | --- | --- | --- | 0.00% (0/25) |

| Score 2 | --- | --- | --- | 80.00% (20/25) | |

| Score 3 | --- | --- | --- | 20.00% (5/25) | |

| Score 4 | --- | --- | --- | 0.00% (0/25) |

HR, heart rate.

Score 1: excellent

Score 2: good

Score 3: adequate

Score 4: not evaluative

Figure 3. .

The percentage of RCA segments (segment 1–4) rated as score 1, 2, three for patients categorized into 10 subgroups. RCA,right coronary artery.

Figure 4. .

The percentage of LAD segments (segment 5–10) rated as score 1, 2, three for patients categorized into 10 subgroups. LAD, left anterior descending.

Figure 5. .

The percentage of LCX segments (segment 11–15) rated as score 1, 2, three for patients categorized into 10 subgroups. LCX, left circumflex.

Discussion

Adjusting the ECG pulsing window is an effective way to reduce radiation dose in CCTA, but the optimal width and timing is highly dependent on patient's HR.21–23 For patients with low and stable HR, a narrow pulsing width can be used in the mid-diastole to achieve dose reduction while maintaining sufficient image quality. At high HR, the efficiency of dose reduction decreases because of subsequent widening of the full tube current window. Hence, HR control is crucial in low-dose CCTA imaging. For clinical routine practice, HR-control medications to achieve a target HR of 65 bpm are usually administered to patients with high HR.24,25 However, the effect of HR control medications may not be always effective because other factors, such as anxiety and nervousness, would also increase patient's HR. Motion artifacts due to high or irregular HR are common limitation of CCTA. Leipsic et al have investigated the feasibility of motion correction reconstruction for patients without receiving HR control medications before undergoing CCTA examination.26 In their study, the mean HR was 71.8 ± 12.7 bpm, and the interpretability of motion corrected CCTA on a per-segment, per-artery and per-patient level was 97%, 96% and 92%, respectively. Since retrospectively ECG gating was used, the effective dose was 13.2 ± 1.8 mSv. The CT system used in their study was a 64-slice MDCT (Discovery HD 750, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI), which has a gantry rotation time of 350 ms and z-coverage value of 40 mm. Using the same CT scanner, Fuchs et al have evaluated the effect of the motion correction algorithm on the image quality of prospectively ECG triggered CCTA with X-ray window at 75% of the R–R interval ±80 ms for patients who received HR-control medications but did not reach the target HR.27 In their study, the mean HR was 69 ± 9 bpm, and the overall interpretability of motion corrected CCTA on a per-segment and per-artery level was 93 and 88%, respectively. Because the minimum ECG-pulsing window was applied in their data acquisition, the mean effective dose was reduced to 2.3 ± 0.8 mSv.

As seen in Table 1, the mean HRs were 56.00 ± 7.01, 63.49 ± 6.02, 71.95 ± 9.42, 74.50 ± 2.12 bpm for patients in phaseD, phaseD:SSF, phaseD + S:SSF and phaseS:SSF, respectively. All vessel segments demonstrated sufficient image quality for clinical diagnosis. On the other hand, the mean effective doses were 4.80 ± 7.01, 4.78 ± 1.46, 4.50 ± 0.94, 4.93 ± 0.55 mSv for patients in phaseD, phaseD:SSF, phaseD + S:SSF and phaseS:SSF, respectively. It has been reported that breath-holding during cardiac CT scan acquisition could lead to the variation of HR.28 In addition, the warm feeling after injection of contrast agent could also affect HR, especially in elderly patients. Hence, the ECG pulsing window after manual adjustment is usually more conservative in dose reduction than that determined automatically by the scanner. For our enrolled patients, CCTA scans acquired using ECG pulsing window at 40–55% + 70–85% of the R–R interval were performed on 61.9%, 86.1%, 90%, 100% of patients in phaseD, phaseD:SSF, phaseD + S:SSF and phaseS:SSF, respectively. Besides the ECG pulsing window, the radiation dose of CCTA scans is also related to the NI used in the AEC system and the blending ratio of FBP and iterative reconstruction. For the 64-slice MDCT scanner used by Leipsic et al and Fuchs et al, a BMI-adapted scanning protocol (not AEC) and 30% blending of ASIR were applied. In addition, the scan pitch adjusted per HR ranged between 0.16 and 0.20. Hence, the radiation dose shown in this study was three times lower than that reported by Leipsic et al but two times higher than that in the study of Fuchs et al. A 50% dose reduction can be achieved for CCTA acquired using ECG pulsing window at 40–55% + 70–85% of the R–R interval by turning off the X-ray beam during systolic phase. However, the image quality of diastolic reconstruction is degraded as the increase of HR since the minimum mid-diastolic velocity increases with increasing HR. Therefore, HR is a key factor to identify patients who are the best suitable candidates for diastolic reconstruction.9–11

According to Table 2, diastolic reconstruction was applied to all vessel segments in patients with HR <63 bpm, where 36.5 and 77.8% of segments were reconstructed with the use of motion correction in HR ≤57 bpm (241 segments) and 58–62 bpm (162 segments), respectively. As for patients with HR ≥63 bpm (402 segments), there were 68 segments reconstructed in diastole and 43 segments reconstructed in systole for the 111 vessel segments in patients categorized as phaseD +S:SSF with HR 63–67 bpm. The corresponding results were 95 and 58 segments for patients categorized as phaseD +S:SSF with HR ≥68 bpm (293 segments). Hence, 89.3% (359/402) and 71.7% (210/293) of segments were reconstructed in diastole in HR 63–67 and ≥68 bpm, respectively, while 81 and 100% of segments were reconstructed with the use of motion correction in the same HR groups. These findings imply that diastolic reconstruction is not only limited for patients with HR <63 bpm.15,16 As seen in Figure 3, there was a slight difference in phaseD between HR ≤57 bpm (score 1: 52%; score 2: 48%) and 58–62 bpm (score 1: 50%; score 2: 50%), while the difference in phaseD between HR 58–62 and 63–67 bpm (score 1: 21%; score 2: 75%; score 3: 4%) becomes more obvious. Beyond HR of 67 bpm, there is no patient belonging to phaseD. With regards to phaseD:SSF, there was a notable difference between HR ≤57 bpm (score 1: 43%; score 2: 57%) and 58–62 bpm (score 1: 20%; score 2: 75%; score 3: 5%), while the difference becomes less obvious between HR 58–62 and 63–67 bpm (score 1: 14%; score 2: 78%; score 3: 8%) and HR 63–67 and ≥68 bpm (score 1: 11%; score 2: 69%; score 3: 19%). Similar situations were also observed in Figures 4 and 5. These results indicate that increasing HR leads to less influence on the image quality of CCTA when the motion correction algorithm was applied to the data for patients with HR >57 bpm. With regards to patients with HR ≤57 bpm, decreasing HR causes tremendous improvement in motion score for patients categorized as phaseD:SSF, but not for patients in phaseD. As seen in Figures 3–5, the best subjective image quality score was in patients categorized as phaseD with HR ≤57 bpm. In other words, CCTA showed the best image quality in patients with low and stable HR, no matter what technique was applied to reduce cardiac motion-related artifacts. It has been reported that the motion correction algorithm is an effective method to reduce cardiac motion-related blurring for patients with intermediate to high HR,29,30 but our results suggest that it efficacy is less obvious in patients with low and stable HR.

Overall, the relationship between HR and optimal reconstruction phase in prospectively ECG-triggered CCTA reconstructed with the use of motion correction was investigated in a 256-slice MDCT. Based on our results, the motion correction function was applied to every patient with HR ≥68 bpm, which is also the only HR group that has patients belonging to phaseS:SSF. Hence, a HR less than 67 bpm can be used to identify appropriate patients for diastolic reconstruction. Our results also demonstrated that the motion correction algorithm is an effective approach to reduce the impact of cardiac motion in CCTA, but HR control is still important to optimize the image quality of CCTA. Several limitations to this study need to be acknowledged. First, it was a retrospective study, and data were obtained from a single institution. To avoid selection bias, data were enrolled consecutively during a specific time period, and image analysis was performed without information about patient's HR and CCTA reconstruction techniques. A multicenter trial with a larger sample size and more observers would be considered in the future. The patient characteristics, practice preferences and patterns of CCTA staff may vary from center to center, so multilevel modeling should be employed to take into account the complex layered data structure. Second, since our study focused on the relationship between HR and CCTA reconstruction techniques, the diagnostic performance of CCTA was not compared with invasive catheter angiography. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the impact of HR-dependent reconstruction techniques on the diagnostic assessment of the coronary arteries with CT. Third, all data were acquired using a 256-slice MDCT developed by one manufacturer. It is difficult to compare our results with other types of CT scanner from different manufacturers.

Conclusion

This study investigated the relationship between HR and optimal reconstruction phase in prospectively ECG-triggered CCTA performed on a newly introduced 256-slice MDCT. Based on our results, a HR less than 67 bpm can be used to identify appropriate patients for diastolic reconstruction. Although the motion correction algorithm is an effective approach to reduce the impact of cardiac motion in CCTA, HR control is still important to optimize the image quality of CCTA. The relationship between HR and optimal reconstruction phase established in this study could be further used to tailor the ECG pulsing window for dose reduction in patients undergoing CCTA performed on the 256-slice MDCT.

Contributor Information

Ching-Ching Yang, Email: cyang@kmu.edu.tw.

Wei-Yip Law, Email: lwy44928@seed.net.tw.

Kun-Mu Lu, Email: T000071@ms.skh.org.tw.

Tung-Hsin Wu, Email: tung@ym.edu.tw.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sun Z, Choo GH, Ng KH. Coronary CT angiography: current status and continuing challenges. Br J Radiol 2012; 85: 495–510. doi: 10.1259/bjr/15296170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mahesh M, Cody DD. Physics of cardiac imaging with multiple-row detector CT. Radiographics 2007; 27: 1495–509. doi: 10.1148/rg.275075045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Qin J, Liu L-yun, Meng X-chun, Zhang J-sheng, Dong Y-xu, Fang Y, et al. Prospective versus retrospective ECG gating for 320-detector CT of the coronary arteries: comparison of image quality and patient radiation dose. Clin Imaging 2011; 35: 193–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sun Z, Ng K-H. Prospective versus retrospective ECG-gated multislice CT coronary angiography: a systematic review of radiation dose and diagnostic accuracy. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81: e94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hirai N, Horiguchi J, Fujioka C, Kiguchi M, Yamamoto H, Matsuura N, et al. Prospective versus retrospective ECG-gated 64-detector coronary CT angiography: assessment of image quality, stenosis, and radiation dose. Radiology 2008; 248: 424–30. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2482071804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. den Harder AM, Willemink MJ, de Jong PA, Schilham AMR, Rajiah P, Takx RAP, et al. New horizons in cardiac CT. Clin Radiol 2016; 71: 758–67. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalisz K, Buethe J, Saboo SS, Abbara S, Halliburton S, Rajiah P. Artifacts at cardiac CT: physics and solutions. Radiographics 2016; 36: 2064–83. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016160079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Machida H, Tanaka I, Fukui R, Shen Y, Ishikawa T, Tate E, et al. Current and novel imaging techniques in coronary CT. Radiographics 2015; 35: 991–1010. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015140181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mok GSP, Yang C-C, Chen L-K, Lu K-M, Law W-Y, Wu T-H. Optimal systolic and diastolic image reconstruction windows for coronary 256-slice CT angiography. Acad Radiol 2010; 17: 1386–93. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paul J-F, Amato A, Rohnean A. Low-Dose coronary-CT angiography using step and shoot at any heart rate: comparison of image quality at systole for high heart rate and diastole for low heart rate with a 128-slice dual-source machine. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 29: 651–7. doi: 10.1007/s10554-012-0110-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Araoz PA, Kirsch J, Primak AN, Braun NN, Saba O, Williamson EE, et al. Optimal image reconstruction phase at low and high heart rates in dual-source CT coronary angiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2009; 25: 837–45. doi: 10.1007/s10554-009-9489-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horii Y, Yoshimura N, Hori Y, Takano T, Inagawa S, Akazawa K, et al. Relationship between heart rate and optimal reconstruction phase in dual-source CT coronary angiography. Acad Radiol 2011; 18: 726–30. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seifarth H, Wienbeck S, Püsken M, Juergens K-U, Maintz D, Vahlhaus C, et al. Optimal systolic and diastolic reconstruction windows for coronary CT angiography using dual-source CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 189: 1317–23. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sun G, Li M, Li L, Li G-y, Zhang H, Peng Z-h. Optimal systolic and diastolic reconstruction windows for coronary CT angiography using 320-detector rows dynamic volume CT. Clin Radiol 2011; 66: 614–20. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Husmann L, Valenta I, Gaemperli O, Adda O, Treyer V, Wyss CA, et al. Feasibility of low-dose coronary CT angiography: first experience with prospective ECG-gating. Eur Heart J 2008; 29: 191–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buechel RR, Husmann L, Herzog BA, Pazhenkottil AP, Nkoulou R, Ghadri JR, et al. Low-Dose computed tomography coronary angiography with prospective electrocardiogram triggering: feasibility in a large population. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57: 332–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Korosoglou G, Marwan M, Giusca S, Schmermund A, Schneider S, Bruder O, et al. Influence of irregular heart rhythm on radiation exposure, image quality and diagnostic impact of cardiac computed tomography angiography in 4,339 patients. data from the German cardiac computed tomography registry. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2018; 12: 34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2017.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Husmann L, Leschka S, Desbiolles L, Schepis T, Gaemperli O, Seifert B, et al. Coronary artery motion and cardiac phases: dependency on heart rate -- implications for CT image reconstruction. Radiology 2007; 245: 567–76. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451061791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS, et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the AD hoc Committee for grading of coronary artery disease, Council on cardiovascular surgery, American heart association. Circulation 1975; 51(4 Suppl): 5–40. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.51.4.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deak PD, Smal Y, Kalender WA. Multisection CT protocols: sex- and age-specific conversion factors used to determine effective dose from dose-length product. Radiology 2010; 257: 158–66. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hausleiter J, Meyer TS, Martuscelli E, Spagnolo P, Yamamoto H, Carrascosa P, et al. Image quality and radiation exposure with prospectively ECG-triggered axial scanning for coronary CT angiography: the multicenter, multivendor, randomized PROTECTION-III study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012; 5: 484–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Achenbach S, Marwan M, Ropers D, Schepis T, Pflederer T, Anders K, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography with a consistent dose below 1 mSv using prospectively electrocardiogram-triggered high-pitch spiral acquisition. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 340–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roobottom CA, Mitchell G, Morgan-Hughes G. Radiation-reduction strategies in cardiac computed tomographic angiography. Clin Radiol 2010; 65: 859–67. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sabarudin A, Sun Z. Beta-Blocker administration protocol for prospectively ECG-triggered coronary CT angiography. World J Cardiol 2013; 5: 453–8. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v5.i12.453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pannu HK, Alvarez W, Fishman EK. Beta-Blockers for cardiac CT: a primer for the radiologist. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006; 186(6 Suppl 2): S341–S345. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leipsic J, Labounty TM, Hague CJ, Mancini GBJ, O'Brien JM, Wood DA, et al. Effect of a novel vendor-specific motion-correction algorithm on image quality and diagnostic accuracy in persons undergoing coronary CT angiography without rate-control medications. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2012; 6: 164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fuchs TA, Stehli J, Dougoud S, Fiechter M, Sah B-R, Buechel RR, et al. Impact of a new motion-correction algorithm on image quality of low-dose coronary CT angiography in patients with insufficient heart rate control. Acad Radiol 2014; 21: 312–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang J, Fletcher JG, Scott Harmsen W, Araoz PA, Williamson EE, Primak AN, et al. Analysis of heart rate and heart rate variation during cardiac CT examinations. Acad Radiol 2008; 15: 40–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li Q, Li P, Su Z, Yao X, Wang Y, Wang C, et al. Effect of a novel motion correction algorithm (SSF) on the image quality of coronary cta with intermediate heart rates: segment-based and vessel-based analyses. Eur J Radiol 2014; 83: 2024–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liang J, Wang H, Xu L, Dong L, Fan Z, Wang R, et al. Impact of SSF on diagnostic performance of coronary computed tomography angiography within 1 heart beat in patients with high heart rate using a 256-Row detector computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2018; 42: 54–61. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]