Abstract

BTB/POZ domain-containing 3 (BTBD3) was identified as a potential risk gene in the first genome-wide association study of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). BTBD3 is a putative transcription factor implicated in dendritic pruning in developing primary sensory cortices. We assessed whether BTBD3 also regulates neural circuit formation within limbic cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuits and behaviors related to OCD in mice. Behavioral phenotypes associated with OCD that are measurable in animals include compulsive-like behaviors and reduced exploration. We tested Btbd3 wild-type, heterozygous, and knockout mice for compulsive-like behaviors including cage-mate barbering, excessive wheel-running, repetitive locomotor patterns, and reduced goal-directed behavior in the probabilistic learning task (PLT), and for exploratory behavior in the open field, digging, and marble-burying tests. Btbd3 heterozygous and knockout mice showed excessive barbering, wheel-running, impaired goal-directed behavior in the PLT, and reduced exploration. Further, chronic treatment with fluoxetine, but not desipramine, reduced barbering in Btbd3 wild-type and heterozygous, but not knockout mice. In contrast, Btbd3 expression did not alter anxiety-like, depression-like, or sensorimotor behaviors. We also quantified dendritic morphology within anterior cingulate cortex, mediodorsal thalamus, and hippocampus, regions of high Btbd3 expression. Surprisingly, Btbd3 knockout mice only showed modest increases in spine density in the anterior cingulate, while dendritic morphology was unaltered elsewhere. Finally, we virally knocked down Btbd3 expression in whole, or just dorsal, hippocampus during neonatal development and assessed behavior during adulthood. Whole, but not dorsal, hippocampal Btbd3 knockdown recapitulated Btbd3 knockout phenotypes. Our findings reveal that hippocampal Btbd3 expression selectively modulates compulsive-like and exploratory behavior.

Subject terms: Psychiatric disorders, Neuroscience

Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a psychiatric disorder characterized by intrusive and unwanted thoughts, images, or urges and/or compulsive behaviors1. Although OCD is often comorbid with anxiety disorders2, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) reclassified OCD into a new category of disorders in which compulsive behavior is the core feature, consistent with recent hypotheses that compulsivity may comprise a transdiagnostic psychiatric trait3,4. Compulsive behaviors are defined as maladaptive repetitive behaviors that are performed despite no longer leading to a goal, and are typically inflexible in nature5–7. Unlike obsessions, compulsive behavior can be operationalized in rodent models. For one, chronic treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), but not other classes of antidepressants including norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), provide effective treatment for OCD8, and reduce compulsive-like behaviors in rodents including route stereotypy, repetitive jumping, and flipping9–12. Furthermore, aspects of compulsive behavior can be measured directly in rodents, such as neuropsychological endophenotypes in cognitive tasks. Our knowledge of the neurobiological underpinnings of compulsive behavior remain incomplete, and animal models provide an important tool for revealing these mechanisms.

The first genome-wide association study (GWAS) of OCD identified rs6131295, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) located near BTB/POZ domain-containing 3 (BTBD3), as genome-wide significant in the trio, but not the case-control, portion of the study13. This SNP was also an expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) for BTBD313, but was not significant in a second GWAS14 or a meta-analysis15. However, these GWASs were perhaps insufficiently powered to identify genome-wide significant loci. The function of BTBD3 has been largely unknown, until a recent report identified a role for BTBD3 in neurodevelopment. BTBD3 was found to orient dendrites toward active axon terminals and regulate activity-dependent dendritic pruning in primary sensory cortex during neonatal development, thus facilitating neural circuit formation16. Yet, whether BTBD3 also performs this function in other brain regions in which it is highly expressed, including limbic cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuits, remains unknown.

In humans and rodents, BTBD3 is highly expressed within limbic CSTC circuitry including the mediodorsal thalamus, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and hippocampus17,18. Within this circuit, BTBD3 expression increases rapidly during early postnatal development and peaks during childhood and adolescence in humans18 and mice16,17. Dysfunction within limbic CSTC circuitry is associated with abnormal repetitive behaviors19,20, and specifically with compulsive behaviors21,22. Furthermore, the hippocampus, mediodorsal thalamus, and ACC are key structures for goal-directed decision-making23–27, which is impaired in OCD28–30, and theorized to underlie expression of compulsive behaviors31,32. Thus, we aimed to determine the role of BTBD3 in the morphological development of this circuit, and in the expression of compulsive-like behaviors.

Herein, we sought to address three key questions: (i) Does Btbd3 expression modulate behaviors related to OCD, such as compulsive-like behaviors? (ii) Does altering Btbd3 expression affect neuronal morphology within the ACC, mediodorsal thalamus, or hippocampus? (iii) In which region of the limbic CSTC circuit does Btbd3 expression regulate behavioral phenotypes observed? To address these questions, we used Btbd3 wild-type (WT), heterozygous (HT), and knockout (KO) mice to assess behavioral phenotypes and dendritic morphology within the mediodorsal thalamus, ACC, CA1, and dentate gyrus. Finally, we generated and used Btbd3flox mice and an adeno-associated virus (AAV) expressing Cre recombinase (Cre) to knockdown (KD) either dorsal or whole hippocampal Btbd3 expression during the early neonatal period, and assessed behavioral consequences during adulthood.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult (minimum 7 weeks) male and female mice were group-housed by sex on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle (~500 lx overhead lighting in housing room) with ad libitum standard chow and water except during cognitive testing (see below). All testing occurred during the light cycle unless otherwise specified. Btbd3 KO mice were on a 129/B6 background (RIKEN, Saitama, Japan). Experimental cohorts were bred in-house and generated from littermates from heterozygous (HT) Btbd3 crosses, resulting in variable group sizes based on breeding production. Minimum sample sizes were targeted based on previous experience with these paradigms. Large cohort sizes were used for assessing barbering, based on previous reports of low barbering frequency in control animals33. Btbd3-floxed (Btbd3flox) mice were generated on a pure C57BL/6J background (Transviragen, Research Triangle Park, NC) using CRISPR/Cas9 to insert loxP sites flanking exon 2 of Btbd3. Mice weighed 16–35 g. Genotype or viral condition, sex, and home cage were counterbalanced across testing. Sample sizes for each test are listed in the figure legends. All procedures were performed in accordance with the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Drugs

Drugs were administered in the drinking water in opaque bottles for 14 weeks. The SRI fluoxetine was administered at 80 mg/L to achieve a 10 mg/kg/day dose and changed weekly. The NRI desipramine was administered at 215 mg/L to achieve a 20 mg/kg/day dose and changed biweekly34,35. Fluoxetine and desipramine were used because chronic treatment with SRIs, but not other classes of antidepressants, serve as effective monotherapy for OCD36,37.

Behavioral studies

Barbering

Mice were pair-housed by sex and genotype, photographed weekly, and inspected for evidence of barbering, an abnormal behavior in which animals repetitively clip or pluck the fur of their cage mates, generating bald spots38. See Supplementary Information.

Cognitive testing

Male mice were food-restricted to 85% of free-feeding bodyweight to motivate responses for food reward, trained to respond on a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule, and then assessed in a Go/No-Go task to measure response inhibition39, progressive ratio breakpoint (PRBP) task to measure motivation for reward40, and finally the probabilistic learning task (PLT) to measure goal-directed and habitual decision-making strategies41. See Supplementary Information.

Wheel-running

In order to track home-cage locomotor activity, mice were singly housed in standard cages equipped with wireless running wheels (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). Wheel revolution counts were continuously transmitted to a computer running Wheel Manager Software (Med Associates) for 7 days in the mouse housing room. Mice that never acclimated to running wheels (such as burying the wheel in bedding; quantified as fewer than 300 total wheel revolutions for the entire week) were excluded (n = 6).

Open field

In order to track locomotor activity in a novel environment, mice were placed in a corner of an open field (OF) apparatus (Accuscan, Columbus, OH) equipped with a central overhead light (~100 lx) and activity was monitored for 45 min in 5-min bins. Versamax software (Accuscan, Columbus, OH) generated primary outcome measures including distance traveled (locomotion), vertical rearing (exploration), and center activity (anxiety). The spatial scaling exponent d (spatial d) was calculated using NightOwl software (Custom) and Python (Python Software Foundation, Beaverton, OR). Spatial d describes the smoothness of the path of the animal, where high values indicate many directional changes, whereas low values indicate a more straight and rigid path, characteristic of compulsive circling in the OF10,11,42.

Dig test

To measure exploration43, mice were placed in novel, clean standard cages with fresh bedding (1″ deep) and recorded for 3 min35. Videos were scored by a blind observer for digging behavior, defined by significant displacement of bedding using forelimbs.

Marble-burying

Marble burying was assessed as an additional measure of exploratory digging44–47. Fresh cages were filled with 5 cm bedding with 12 marbles placed on top in a 3 × 4 grid with 4 cm center-to-center spacing. Number of marbles buried to 2/3 depth was recorded after 30 min44.

Nest-building

Nest-building is a measure of well-being in mice48. Mice were given a pre-weighed compressed cotton nestlet (Ancare, Bellmore, NY) while singly housed in the home cage49. In the 8-h version, nestlets were removed 8 h later and any unused nestlet was weighed. In the overnight version, nestlets were provided just before initiation of the dark cycle. Fourteen hours later, any unused nestlet was weighed.

Light-dark test

The light-dark test was performed to assess anxiety-like behavior50. The light-dark test was performed in the OF (overhead light adjusted to ~40 lx) using dark inserts to cover half the chamber (Omnitech Electronics, Inc., Columbus, OH, USA). Animals began in the dark side of the chamber and activity was recorded for 10 min. Outcome measures were duration on each side, proportion of distance traveled in the dark, and latency to enter the light side.

Novelty-induced hypophagia (NIH)

NIH testing assesses anxiety, and was performed as previously described51. Briefly, mice underwent three days of training to consume sweetened condensed milk. The following day, mice were presented with sweetened condensed milk in the home cage for 30 min. Latency to drink and consumption volume were measured. The following day, mice were presented with sweetened condensed milk in a novel cage with no bedding and bright lighting for 30 min. Latency to drink and consumption volume were recorded.

Forced swim test (FST)

Animals were tested in the FST to assess depression-like behavior52. Mice were placed in opaque plastic buckets (18 cm × 20.5 cm) filled with 23–25 oC water for 6 min. The day prior to testing, animals underwent a 15 min pretest under the same conditions. Each session was recorded. The video from the test day was hand-scored by a blind observer for time spent immobile, swimming, or climbing in the final 4 min.

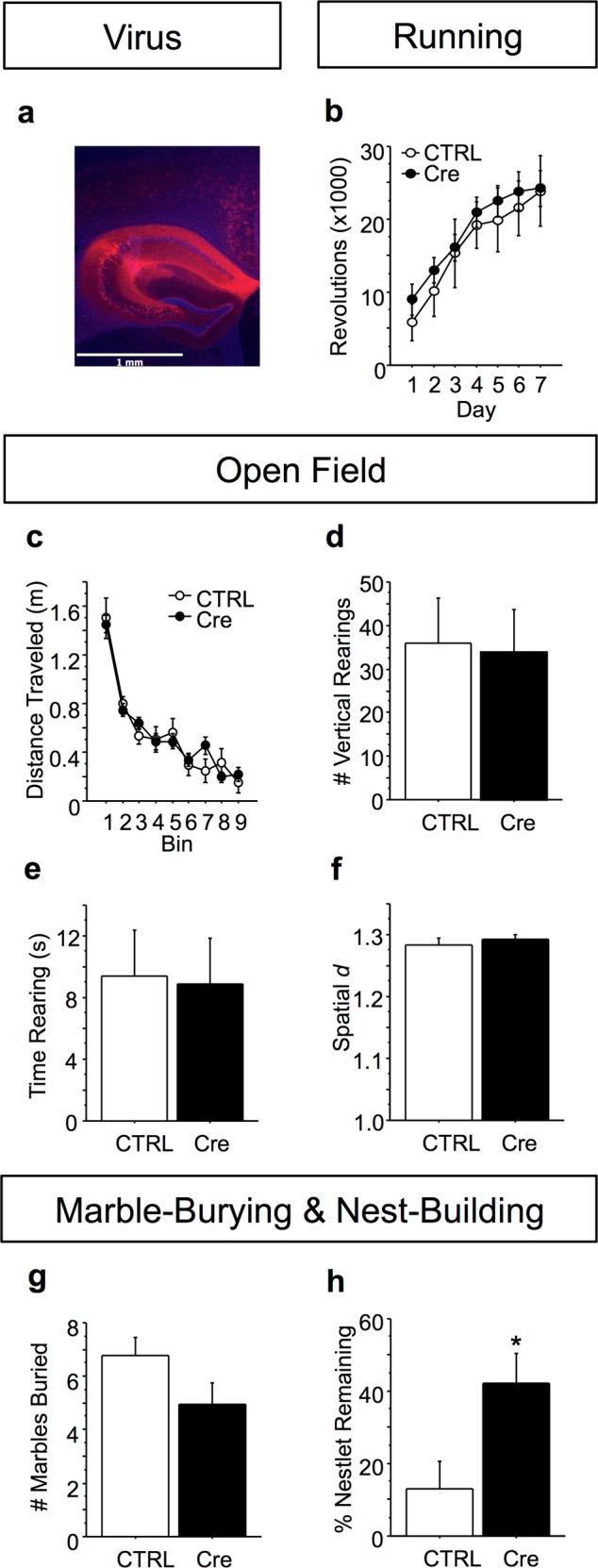

Viral-mediated Btbd3 knockdown

In order to assess the role of hippocampal Btbd3 expression in behavior, postnatal day 2 Btbd3flox mouse pups received intracranial infusions of AAV expressing Cre: AAV2/8-CMV-Cre-P2A-tdTomato-WPRE (AAV-Cre; Viral Vector Core Facility, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) or control: AAV2/8-CMV-tdTomato-WPRE (AAV-tdTomato), targeting the whole hippocampus (0.3 mm anterior, 2.0 mm lateral, 2.5 mm ventral of lambda), or only the dorsal half of the hippocampus (1.0 mm anterior, 0.3 mm lateral, 2.7 mm ventral of lambda). See Supplementary Information. Mice were assessed for behavior during adulthood (8–13 weeks) in a subset of paradigms tested in the global Btbd3 KO mice.

Statistical analysis

Dependent measures were analyzed using repeated measures or factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significant interactions were resolved by assessing simple main effects for factors with more than two groups with Bonferroni correction. Post hoc tests for between-subjects factors were performed using Student–Newman–Keuls. Where appropriate, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVAs were performed, and Mann–Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction were used as post hoc tests. Categorical dependent measures were analyzed using chi-square tests for endpoint factors which were confirmed with a bootstrap analysis, and Kaplan–Meier survival curves with Mantel–Cox logrank tests for repeated measures analyses. Alpha was set at 0.05. A few mice were excluded from analyses because of experimental errors, but no statistical outliers were removed.

Results

Btbd3 KO mice exhibit compulsive-like behavior

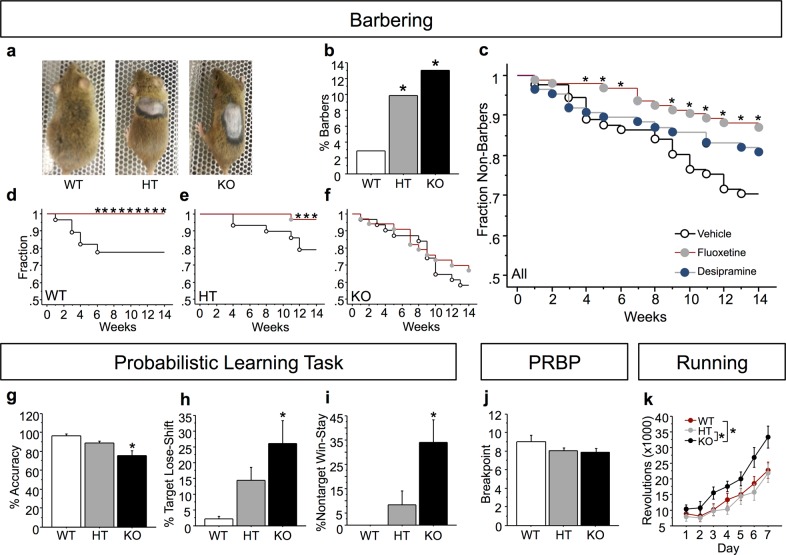

We observed a high frequency of cage-mate barbering in Btbd3 KO colony home cages (Fig. 1a); therefore, we monitored barbering behavior by pair-housing mice of identical sex and genotype. Chi-square analysis revealed that barbering was unevenly distributed across the three genotypes (Fig. 1b; Χ2(2, n=647) = 11.38; p < 0.005). Btbd3 HT (Χ2(1, n=486) = 7.73; p < 0.01) and KO (Χ2(1, n=332) = 11.77; p < 0.0001) groups each had an increased incidence of barbering compared to WT. A bootstrap analysis (100,000 iterations) confirmed that all of the chi-square statistics above were unlikely (p’s < 0.05) to be due to the uneven group numbers that resulted from heterozygous breeding in this observational cohort. Bald patches in the fur were observed primarily on the dorsal surface of the body and the face, characteristic of barbering by cage mates, rather than self-barbering33.

Fig. 1. Btbd3 knockout induces compulsive-like behavior.

a Representative example photographs of dorsal surface of the coat in BTBD3 WT (left), HT (middle), and KO (right) mice. b Increased incidence of barbering behavior was identified in Btbd3 HT and KO mice in a chi-square analysis (n = 81 female/90 male WT, 150 female/165 male HT, 83 female/78 male KO mice). Across genotypes c, chronic fluoxetine reduced onset of barbering over time in a cohort of initially 100% non-barbers, whereas desipramine did not significantly alter barbering behavior at any time point in a Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis (n = 15 female/13 male WT, 16 female/15 male HT, and 19 female/12 male KO for vehicle treatment, 19 female/13 male WT, 13 female/12 male HT, and 14 female/16 male KO for desipramine treatment, and 14 female/14 male WT, 16 female/17 male HT, and 19 female/15 male KO mice in the fluoxetine treatment group). Drops indicate time points when mice began to barber a cage mate, with the cumulative fraction of non-barbers indicated on the Y-axis. Within Btbd3 WT mice d, fluoxetine completely prevented onset of barbering behavior. Within Btbd3 HT mice e, fluoxetine-reduced barbering behavior. Within Btbd3 KO mice f, barbering was unaffected by fluoxetine treatment. g Btbd3 KO mice showed reduced accuracy on the PLT (n = 13 WT, 16 HT, 17 KO mice, all male), which was driven by an increased frequency of lose-shift responses on the target port h and an increased frequency of win-stay responses on the non-target port i. j Breakpoint was unaffected by Btbd3 genotype in the PRBP task in an ANOVA. k Btbd3 KO mice exhibited excessive wheel-running behavior during the dark cycle (n = 10 WT, 9 HT, and 10 KO mice of each sex). Results are expressed as mean values ± SEM, except for panels depicting categorical data, which does not have error. *p < .05 vs. WT or vehicle groups in a chi-square analysis b, log-rank analysis c–f, or an ANOVA with post hoc tests g–k. WT wild-type, HT heterozygous, KO knockout, PLT probabilistic learning task, PRBP progressive ratio breakpoint task

We then assessed the effects of OCD-effective (SRI fluoxetine) or OCD-ineffective antidepressant treatment (NRI desipramine) on barbering36,37 for 14 weeks to determine whether barbering may be a compulsive-like phenotype. Pooled across genotypes, log-rank tests revealed that fluoxetine reduced the onset of barbering relative to vehicle starting at 4 weeks of treatment (Fig. 1c), and throughout the remainder of treatment, except for weeks 7 and 8 (Supplementary Information). In contrast, desipramine did not affect onset of barbering (Χ2(1, n=177) = 2.09; p = 0.15). Furthermore, within fluoxetine-treated animals, a genotype effect was identified (X2(2, n=95) = 16.75; p < 0.0005). Therefore, the effect of fluoxetine on barbering within each genotype was examined. Within Btbd3 WT mice, fluoxetine prevented barbering onset (Fig. 1d), and this effect was significant by 6 weeks of treatment (Χ2(1, n=56) = 4.59; p < 0.05). Within Btbd3 HT mice, fluoxetine became effective at 12 weeks of treatment (Fig. 1e; Χ2(1, n=64) = 4.50; p < 0.05) and remained significant through week 14 (Χ2(1, n=64) = 4.50; p < 0.05). In contrast, fluoxetine never affected Btbd3 KO barbering incidence (Fig. 1f; week 14: Χ2(1, n=65) = 0.40; p = 0.53). These effects were not due to genotypic differences in fluoxetine metabolism (Supplementary Information).

Next, we tested cognitive domains relevant to compulsive disorders using operant conditioning. ANOVAs revealed that there was no effect of genotype on FR1 training (F(2,49) = 0.27; p = 0.76) or on false alarm rate in the Go/No-Go task (Supplementary Information), which measures response inhibition39,53. In the PLT, which measures reinforcement learning and response strategies41, no effects of genotype were identified for Block 1 (reward probabilities of 90%/10%) or Block 2 (reward probabilities of 80%/20%; data not shown). However, in Block 3 (reward probabilities of 70%/30%), Btbd3 KO mice were less accurate than WT or HT mice (Fig. 1g; F(2,35) = 8.01; p < 0.005). An ANOVA and post hoc tests revealed a higher proportion of target lose-shift responses in Btbd3 KO mice versus WT mice (F(2,35) = 4.96; p < 0.05; Fig. 1h). Furthermore, Btbd3 KO mice more frequently reselected the non-target port after being rewarded than WT mice (Fig. 1i; F(2,23) = 4.24; p < 0.05). Genotype did not affect target win-stay or non-target lose-shift patterns (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e). Lastly, mice were assessed in the PRBP test for any potentially confounding effects of genotype on motivation in the PLT, but genotype did not affect breakpoint (Fig. 1j; F(2,43) = 1.58; p = 0.22).

Next, wheel-running was assessed, which is excessive in some rodent models of compulsive behavior54. A three-way interaction of day, cycle, and genotype was identified by a repeated measures ANOVA for wheel revolutions (F(12,312) = 2.32; p < 0.01). Post hoc ANOVAs and then post hoc tests revealed that Btbd3 KO mice accrued more wheel revolutions than WT or HT mice during the dark cycle (Fig. 1k; F(2,55) = 4.57; p < 0.05), but not the light cycle (F(2,55) = 0.35; p = 0.70; data not shown).

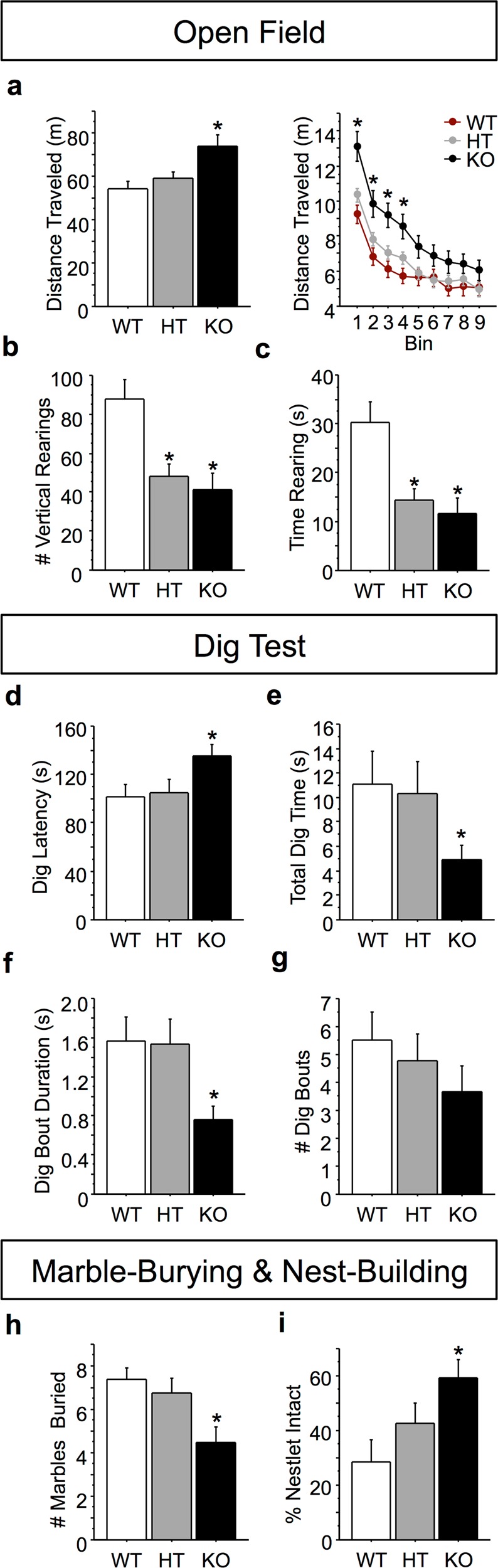

Btbd3 KO mice show reduced exploration

We next assessed exploration in Btbd3 mice, as novelty-seeking is reduced in OCD55–58. In the OF test, a genotype by bin interaction (F(16,1040) = 2.57; p < 0.0001) in a repeated measures ANOVA and post hoc tests revealed that Btbd3 KO mice traveled a greater total distance than WT or HT mice in bins 1–4 (Fig. 2a). All genotypes exhibited locomotor habituation (Supplementary Information). Btbd3 HT and KO mice had reduced instances of vertical rearing relative to WT mice (Fig. 2b; F(2,130) = 6.97; p < 0.005) and spent less time rearing than WT mice (Fig. 2c; F(2,130) = 7.18; p < 0.005).

Fig. 2. Btbd3 knockout reduces exploration.

a Btbd3 KO mice traveled a greater total distance in the OF (n = 17 female/27 male WT, 34 female/27 male HT, and 11 female/20 male KO mice) than HT or WT mice overall (left panel), which was confined to the first 20 min of testing as revealed by the 5-min bin analysis (right panel). b Btbd3 HT and KO mice showed fewer instances of vertical rearing and c spent less time rearing across the session than WT mice in the OF. d–g In the dig test (n = 13 female/14 male WT, 15 female/16 male HT, 20 female/13 male KO mice), Btbd3 KO mice had a greater latency to initiate digging behavior d, reduced total time spent digging e, and dug in briefer bouts than controls f. The number of dig bouts in the dig test was unaffected by Btbd3 genotype g. h Btbd3 KO mice buried fewer marbles (n = 14 female/12 male WT, 12 female/12 male HT, 9 female/13 male KO mice) than WT mice in the marble-burying test. i Btbd3 KO mice left a greater portion of the nestlet intact than WT mice in the 8-h nest-building paradigm (n = 12/genotype/sex). Results are expressed as mean values ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. WT group in ANOVAs resolved with post hoc tests. WT wild-type, HT heterozygous, KO knockout, OF open field

Btbd3 mice were then assessed for exploratory digging. The distribution of the data violated the normality assumption for using parametric tests even after attempts at transforming the data, so nonparametric statistics were used. A Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA found a main effect of genotype on latency to dig (H(2) = 6.43; p < 0.05), with Btbd3 KO mice showing a longer latency to dig than WT mice (Fig. 2d; U = 289; p < 0.025). Furthermore, Btbd3 KO mice spent less time digging than WTs (Fig. 2e; H(2) = 5.93; p < 0.05; U = 286; p < 0.025). Lastly, genotype altered bout duration (H(2) = 8.20; p < 0.05), with Btbd3 KO mice performing briefer digging bouts than WT mice (Fig. 2f; U = 265; p < 0.025). No effect of genotype was identified for number of digging bouts (Fig. 2g; H(2) = 4.36; p = 0.11).

Btbd3 mice were tested in the marble-burying paradigm to confirm genotype effects on digging behavior44–47. An ANOVA and post hoc tests revealed that Btbd3 KO mice buried fewer marbles than WT or HT mice (Fig. 2h; F(2,66) = 5.56; p < 0.01).

Nest-building is considered a measure of well-being in mice48, and nest-building deficits have been found in numerous neuropsychiatric disorder models59–62. In the nest-building task, a main effect of genotype was identified for original nestlet percentage remaining intact in an ANOVA (F(2,65) = 4.33; p < 0.05), with post hoc tests showing that Btbd3 KO mice left more nestlet untouched than WT mice (Fig. 2i).

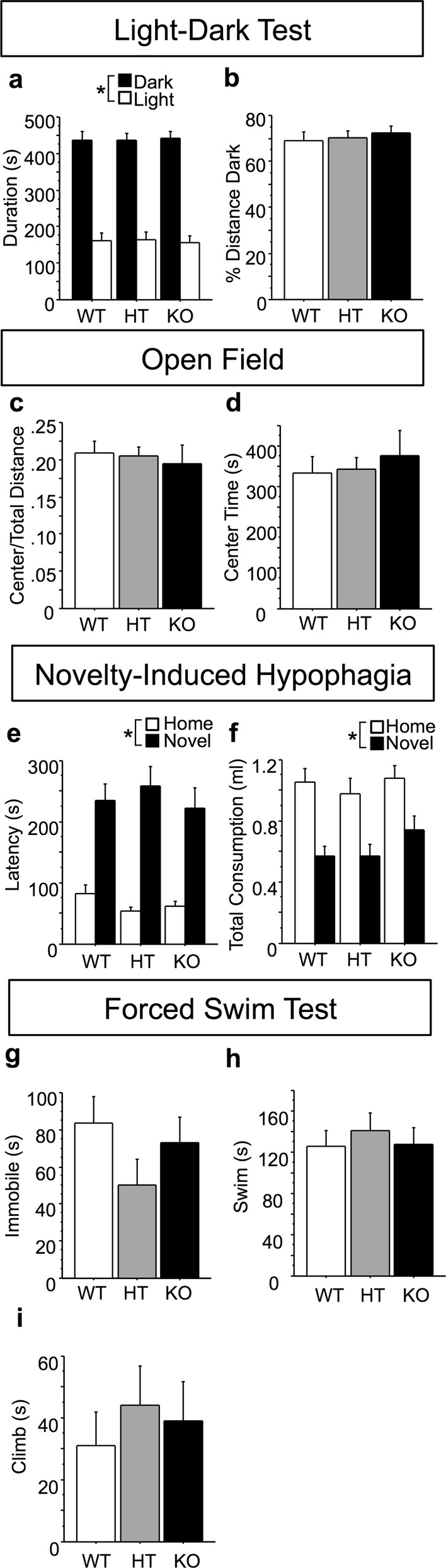

Btbd3 does not modulate anxiety-like or depression-like behaviors or basic sensory and motor functioning

Anxiety and depression are often comorbid with OCD2,63. Thus, Btbd3 mice were assessed for anxiety-like and depression-like behaviors. In the light-dark test, no effects of genotype were identified for either duration on the light versus the dark side of the chamber (Fig. 3a) or percent distance traveled in the dark side (Fig. 3b). An ANOVA revealed a main effect of side of the chamber for duration (F(1,84) = 140.97; p < 0.0001), indicating that animals spent more time on the dark side. In the OF test, no effect of genotype was identified for proportion of distance traveled in the center (Fig. 3c) or time spent in the center (Fig. 3d). Mice were assessed in the NIH test as an additional measure of anxiety-like behavior. Since latency data are often skewed, we examined the distribution of the data, and as a result log-transformed latency to drink for statistical analysis. Neither a main effect of genotype nor an interaction between genotype and cage condition was identified for latency to drink (Fig. 3e). A main effect of cage condition on latency to drink was identified (F(1,49) = 152.30; p < 0.0001), indicating a longer latency to consume the sweetened condensed milk in the novel cage. No effects of genotype were found for total consumption (Fig. 3f). A main effect of cage condition was identified for total consumption (F(1,51) = 102.50; p < 0.0001), indicating reduced consumption of sweetened condensed milk in the novel versus the home cage.

Fig. 3. BTBD3 does not affect anxiety-like or depression-like behavior.

Btbd3 genotype had no effect on proportion of time spent a or distance traveled b in the dark side of the light-dark box (n = 15/genotype/sex), proportion of distance traveled c or time spent in the center d of the OF (n = 17 female/27 male WT, 34 female/27 male HT, and 11 female/20 male KO mice), total latency to drink e, or total consumption f of sweetened condensed milk in the NIH (n = 10 each female/male WT, 10 female/9 male HT, 9 each female/male KO mice), time spent immobile g, swimming h, or climbing i in the FST (n = 10/genotype/sex, except female WT n = 9). Results are expressed as mean values ± SEM. *p < 0.05 between conditions (dark versus light; home versus novel cage) as determined by ANOVAs. OF open field, NIH novelty-induced hypophagia, FST forced swim test

Btbd3 mice were assessed in the FST to evaluate depression-like behavior. No effect of genotype was identified for time spent immobile (Fig. 3g), swimming (Fig. 3h), or climbing (Fig. 3i).

Finally, basic sensorimotor functioning was assessed in Btbd3 mice to screen for potentially confounding effects on compulsive-like and exploratory behaviors. No effects of genotype were found in auditory, olfactory, somatosensory, or motor function (Supplementary Fig. 1f, g; 2). See Supplementary Information.

Effects of Btbd3 expression on limbic CSTC dendritic morphology

Dendritic morphology was assessed in limbic CSTC brain regions with dense Btbd3 expression because BTBD3 was previously reported to play a role in dendritic morphology16. No effects of genotype were identified for dendritic branching or spine density in the CA1 or dentate gyrus subregions of hippocampus, or in the mediodorsal thalamus. However, increased spine density in Btbd3 KO mice was identified in the ACC (Supplementary Fig. 3). See Supplementary Information.

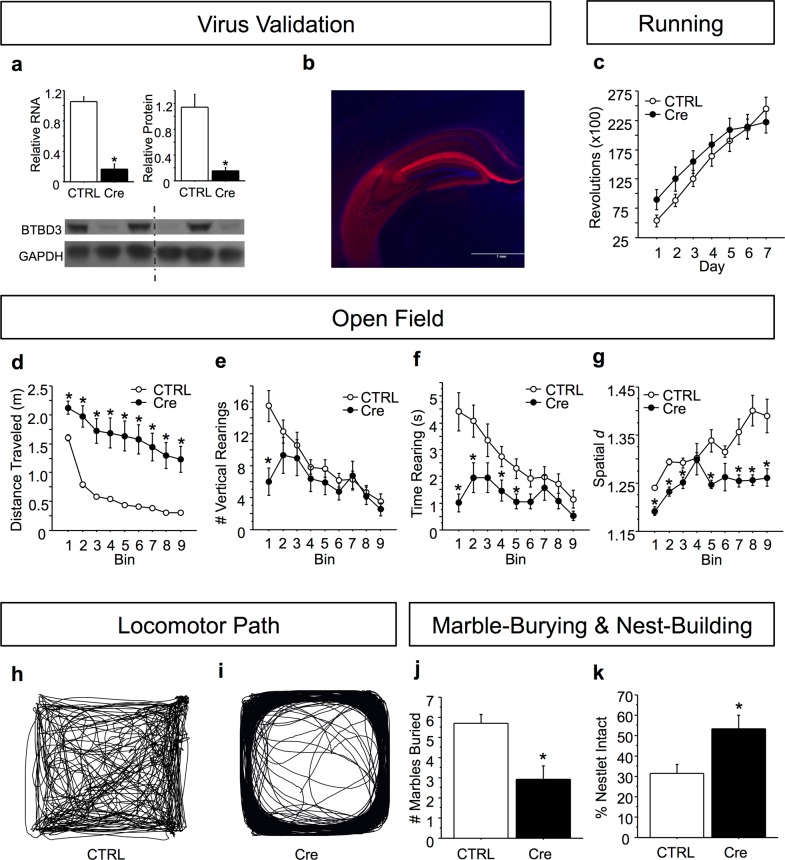

Whole hippocampal Btbd3 KD induces compulsive-like behavior and decreases exploration

Due to robust Btbd3 expression in hippocampus17 and the role of hippocampus in several behavioral phenotypes for which deficits were identified in Btbd3 KO mice45,64, we assessed the effects of neonatal, whole hippocampal Btbd3 KD on behavior during adulthood. We confirmed KD of Btbd3 RNA (Fig. 4a, top left panel; F(1,7) = 46.39; p < 0.0005) and protein (Fig. 4a, top right panel; F(1,4) = 22.10; p < 0.01) in the hippocampus of Btbd3flox mice receiving viral infusion of AAV-Cre versus AAV-tdTomato. Btbd3 KD did not alter wheel-running (Fig. 4c), but increased locomotor activity (Fig. 4d; F(1,70) = 48.85; p < 0.0001) and reduced locomotor habituation in the OF (Supplementary Information). Btbd3 KD mice had reduced instances of rearing within the first 5 min (Fig. 4e; F(8,560) = 3.93; p < 0.0005). For time spent rearing (Fig. 4f), an interaction between viral condition and bin (F(8,560) = 3.49; p < 0.001) and post hoc tests revealed that Btbd3 KD mice spent less time rearing than control mice in time bins 1, 2, 4, and 5. Btbd3 KD mice exhibited reductions in spatial d within each time bin (Fig. 4g), except bins 4 and 6 (Fig. 4h, i; F(8,504) = 2.32; p < 0.05).

Fig. 4. Neonatal Btbd3 knockdown in whole hippocampus recapitulates the Btbd3 knockout phenotype.

Cre virus successfully knocked down RNA (a, top left) and protein (a, top right; bottom) in hippocampus in a qPCR assay (n = 7 AAV-tdTomato, 2 AAV-Cre virus) and a western blot (n = 3/virus) relative to CTRL, respectively. The western blot image (a, bottom) shows samples from CTRL virus-infused mice in lanes 1, 3, and 5, and samples from Btbd3 KD mice in lanes 2, 4, and 6. The dotted line indicates that the image was interrupted between these lanes in order to remove space between the lanes, but the left and right-hand sides are from the same image of the blot. b Representative example of viral reporter tdTomato expression in hippocampus. c Hippocampal Btbd3 KD did not affect number of wheel revolutions in the voluntary home cage wheel-running assessment (n = 19 female/25 male AAV-tdTomato and 15 female/12 male AAV-Cre infused mice). d Hippocampal Btbd3 KD increased distance traveled in the OF throughout testing (n = 19 female/26 male AAV-tdTomato and 16 female/13 male AAV-Cre infused mice). e Hippocampal Btbd3 KD reduced instances of vertical rearing only within the first 5-min bin. f Hippocampal Btbd3 KD reduced time spent rearing in the first half of testing. g Hippocampal Btbd3 KD reduced spatial d throughout testing (example traces in h, i). Hippocampal Btbd3 KD mice buried fewer marbles in the marble-burying paradigm (n = 19 female/26 male AAV-tdTomato and 16 female/13 male AAV-Cre infused mice) j and left more nestlet unused in the overnight nest-building test k than CTRL mice (n = 19 female/26 male AAV-tdTomato and 16 female/13 male AAV-Cre infused mice). Results are expressed as mean values ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. CTRL group in ANOVAs resolved with post hoc tests. KD knockdown, CTRL control virus: AAV-tdTomato, OF open field, AAV adeno-associated virus, qPCR quantitative polymerase chain reaction, Cre AAV-Cre virus

Btbd3 KD mice buried fewer marbles than control mice in the marble-burying test (Fig. 4j; F(1,70) = 10.87; p < 0.005) and used less nestlet than control mice in the nest-building test (F(1,70) = 6.47; p < 0.05) as determined by an ANOVA followed by post hoc tests (Fig. 4k).

Dorsal hippocampal Btbd3 KD does not mimic the Btbd3 KO phenotype

Next, we investigated whether Btbd3 KD in dorsal hippocampus, which was recently implicated in goal-directed planning26, would be sufficient to induce the Btbd3 behavioral profile. No effect of Btbd3 KD was identified on wheel-running (Fig. 5b), distance traveled (Fig. 5c), instances or time spent rearing (Fig. 5d, e), spatial d (Fig. 5f), or marble-burying (Fig. 5g; F(1,25) = 1.85; p = 0.19) in ANOVAs. The only effect of neonatal Btbd3 KD in dorsal hippocampus was impaired nest-building in the nest-building test (Fig. 5h; F(1,25) = 4.58; p < 0.05).

Fig. 5. Neonatal Btbd3 knockdown in dorsal hippocampus does not recapitulate the Btbd3 knockout phenotype.

a Example of viral reporter tdTomato expression in dorsal hippocampus. b Dorsal hippocampal Btbd3 KD did not affect number of revolutions in wheel-running (n = 5 female/4 male AAV-tdTomato, 9 female/9 male AAV-Cre mice), c distance traveled in the OF (n = 5 female/4 male AAV-tdTomato, 11 female/9 male AAV-Cre mice), vertical rearing in the OF d, e, spatial d in the OF f, or g marble-burying (n = 5 female/4 male AAV-tdTomato, 11 female/9 male AAV-Cre mice). h Neonatal dorsal hippocampal Btbd3 KD mice left more nestlet unused than CTRL mice in the nest-building paradigm (n = 5 female/4 male AAV-tdTomato, 11 female/9 male AAV-Cre mice). Results are expressed as mean values ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. CTRL group in ANOVAs resolved with post hoc tests. KD knockdown, CTRL control virus: AAV-tdTomato

Discussion

Our results show that BTBD3 regulates compulsive-like and exploratory behaviors across multiple paradigms in mice. Btbd3 HT and KO mice exhibited increased barbering, which was reduced by effective (SRI), but not ineffective (NRI), OCD treatment. Additionally, Btbd3 KO mice exhibited excessive wheel-running and poor goal-directed decision-making, a trait that is thought to underlie compulsive behavior. Btbd3 HT and KO mice were less exploratory in the OF, dig, and marble-burying tests. Furthermore, whole hippocampal, but not dorsal, neonatal Btbd3 KD increased compulsive-like behaviors and reduced exploration during adulthood, largely mimicking the phenotype of constitutive Btbd3 KO mice. Surprisingly, Btbd3 knockout spared dendritic morphology within hippocampal subregions, but increased spine density in ACC layer II/III pyramidal neurons, suggesting that an alternative function of Btbd3 may mediate the hippocampus-dependent behavioral effects observed. Our findings indicate that reduced hippocampal Btbd3 expression leads to the development of compulsive-like behaviors and reductions in exploration.

Btbd3 HT and KO mice exhibited compulsive-like behaviors indicated by increased barbering, wheel-running, and impaired goal-directed behavior. Barbering is an abnormal behavior observed only in confined animals38, and is considered a repetitive, compulsive-like behavior33,54,65. The idea that barbering is a compulsive-like behavior is reinforced by our finding that chronic SRI, but not NRI, treatment reduced barbering, paralleling treatment response in OCD8. Interestingly, our finding that barbering incidence was reduced by chronic fluoxetine treatment in Btbd3 WT and HT, but not KO mice suggests that Btbd3 expression may be required for these anti-compulsive effects of fluoxetine. Increased barbering has previously been reported in other genetically altered mouse lines exhibiting a compulsive-like phenotype66, and has been associated with deficits in extradimensional shifting65, which measures cognitive flexibility7 and is deficient in OCD67–69. While excessive wheel-running has also been proposed as compulsive-like in rodent food restriction-induced hyperactivity models based on the pharmacological response profile70,71, effects across studies are not fully consistent with OCD72. Thus, the relationship between excessive wheel-running and compulsivity appears somewhat unclear73. Alternatively, other mouse lines exhibiting a compulsive-like phenotype have also reported increased barbering and excessive wheel-running54, suggesting that these phenotypes may be linked. In addition to increased barbering and wheel-running, Btbd3 KO mice also exhibited impaired decision-making in the PLT, which assesses the balance of goal-directed versus habitual decision-making strategies during reinforcement learning41,74. Compulsive behavior has been associated with alterations in this balance, with a shift toward more habitual, and less goal-directed tendencies3,4, as observed in OCD patients28–30. Thus, goal-directed learning impairments are thought to contribute to the development of compulsivity31,32. Therefore, the reduction in goal-directed decision-making we observed in Btbd3 KO mice is consistent with the increases in barbering and wheel-running we also observed in these mice. That Btbd3 KO mice exhibit multiple different compulsive-like phenotypes is consistent with evidence that discrete types of repetitive behaviors are interrelated and subserved by partially overlapping CSTC circuitry19.

Btbd3 HT and KO mice also exhibited reduced exploratory drive. Robust reductions in vertical rearing were found in Btbd3 HT and KO mice. Btbd3 KO mice also showed reduced digging43 and marble-burying. While increased marble-burying has been widely used as a measure of anxiety-like or compulsive-like behavior, this behavior is reduced by many compounds that are ineffective treatments for anxiety or compulsivity73,75, including acute treatment with SRIs76. Furthermore, several rodent models of abnormal repetitive behavior exhibit reductions in marble-burying, concomitant with reduced digging or vertical rearing behavior77–79. Thus, marble-burying has also been suggested to measure exploration44–46. Interestingly, exploration is an integral component of goal-directed behavior80, suggesting that these two impairments in Btbd3 KO mice might be related. Moreover, novelty-seeking, a trait that drives exploration, is reduced in patients with OCD55–58. Lastly, Btbd3 KO mice also showed impaired nest-building, which has been associated with reduced well-being48.

Interestingly, anxiety-like and depression-like behaviors were unaltered in Btbd3 HT and KO mice. Anxiety-like behavior was unaffected in the light-dark, OF, and NIH tests, well-established anxiety measures in rodents. These results strongly suggest that reduced exploration in Btbd3 HT and KO mice does not reflect augmented anxiety, consistent with previous reports that exploration and anxiety-like behavior are dissociable81. Furthermore, depression-like behavior was unaffected by genotype in the FST. Thus, our findings suggest that the behavioral phenotypes observed in Btbd3 KO mice are not modulated by anxiety-like or depression-like states. While anxiety and depression are highly comorbid with OCD2,63, anxiety and affective disorders are distinct from OCD. For example, traits characteristic of OCD, eating disorders, and addiction correlate with goal-directed behavior deficits in humans, whereas anxiety and depression do not3, suggesting distinct neuropsychological endophenotypes between these classes of disorders. Moreover, SRIs and NRIs serve as effective treatment for anxiety and depression82–85, whereas only SRIs provide effective monotherapy in OCD8, a treatment profile that parallels our barbering results. This distinction is further reflected in the DSM-5, which removed OCD from the anxiety disorders category and does not include anxiety as a core symptom of OCD1. Thus, our results suggest that BTBD3 may modulate neural processes contributing to compulsive-like behaviors, including impaired exploratory drive and/or reduced goal-directed behavior, which are independent of anxious-depressive phenotypes. The Btbd3 behavioral profile is thus distinct from several genetic mouse models of OCD, which exhibit a repetitive behavior, such as excessive self-grooming or self-barbering concomitant with increased anxiety-like behaviors66,86,87.

We did not observe effects of Btbd3 genotype on additional behavioral measures including motivation, startle, or sensorimotor behaviors. Motivation was unaltered in Btbd3 HT and KO mice in the PRBP, as was response inhibition as indicated by false alarm rate in the Go/No-Go task (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Btbd3 HT and KO mice also did not show differences in sensorimotor gating (Supplementary Fig. 1f) or startle reactivity (Supplementary Fig. 1g). Furthermore, no effects of Btbd3 genotype were observed on sensory or motor measures in the olfactory dis/habituation or olfactory memory tests, the whisker-brushing test, or the footprint test (Supplementary Fig. 2a–i). Young adult Btbd3 KO mice had modestly reduced bodyweight, which was unlikely to confound the other tests performed (Supplementary Fig. 2j): although, we note the common genetic variation overlap between OCD and anorexia nervosa, and the negative genetic correlation of both with body mass index88. Lastly, no effects of sex were found for the phenotypic differences identified.

Neonatal Btbd3 KD in the whole hippocampus induced compulsive-like behavior and reduced exploration during adulthood, mirroring the phenotype observed in constitutive Btbd3 KO mice, with minor exceptions. Although both models showed exploration deficits, increased locomotion in the OF, and increased compulsive-like behavior, hippocampal Btbd3 KD mice showed decreased spatial d but unaltered wheel-running, while constitutive Btbd3 KO mice showed the opposite pattern. These discrepancies may reflect different compensatory changes or distinct Btbd3 expression patterns. We did not assess barbering in the Btbd3 KD cohorts due to the large sample sizes required for these observations. Interestingly, a pharmacological mouse model of aspects of OCD shows a highly similar behavioral profile, in which 5-HT1B receptor stimulation induces hyperactivity, low spatial d, reduced vertical rearing, reduced exploratory digging, and impaired delayed alternation performance10,11,35,89. This observation further suggests that reduced species-typical exploratory behaviors may be causally related to increased compulsive-like behaviors. Importantly, neonatal Btbd3 KD in the dorsal half of the hippocampus did not produce any of the behavioral effects of whole hippocampal Btbd3 KD, except for nest-building deficits. Altogether, our findings suggest that Btbd3 KD in the whole, but not dorsal, hippocampus induces compulsive-like behavior and reductions in exploration.

Surprisingly, Btbd3 genotype altered dendritic morphology in ACC layer II/III pyramidal neurons, but not in the mediodorsal thalamus, or CA1 or dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Supplementary Fig. 3). This result was unexpected given the important role of BTBD3 in dendritic morphology in the developing barrel cortex16, and suggests that additional region-specific functions of BTBD3, or compensatory changes in constitutive Btbd3 KO mice produced the observed phenotypes. For instance, BTBD3 interacts with cell signaling proteins, such as SEC24C, which is required for trafficking the serotonin transporter to the cell membrane90,91, and CLTC, clathrin heavy chain protein, which is integral to synaptic transmission90,92. Only ACC layer II/III pyramidal neurons had increased spine density in Btbd3 KO mice, which might reflect alterations in the hippocampus-to-ACC circuit, which is implicated in goal-directed behavior93. Indeed, neonatal ventral hippocampal lesions in rodents are thought to disrupt the development of prefrontal circuitry94 and enhance mesolimbic dopamine signaling95, resulting in extradimensional shifting deficits, hyperactivity, increased apomorphine-induced stereotypy, and reduced rearing, marble-burying, and habituation to novelty96–99. This behavioral profile is similar to the phenotype of Btbd3 KO and hippocampal Btbd3 KD mice, and aligns with the minimal behavioral effects of dorsal hippocampus-specific Btbd3 KD. While speculative, our results suggest the possibility that loss of BTBD3 primarily in the ventral hippocampus may produce the observed phenotype through disruption of CSTC circuitry.

To our knowledge, our results comprise the first evidence for a role of Btbd3 in behavior, which is to modulate compulsive-like and exploratory behaviors in mice. Our results support the possibility that the SNP rs6131295, an eQTL for BTBD3, may be of relevance to neuropsychiatric disorders, despite only exceeding the genome-wide significance threshold in the trio portion of an OCD GWAS13. Indeed, OCD patients exhibit compulsive behaviors, goal-directed behavior deficits28–30, and reduced novelty-seeking55–58. However, other neuropsychiatric disorders exhibit one or more of these phenotypes, including autism spectrum disorder100,101, addiction4, and binge-eating disorder4, suggesting the potential relevance of BTBD3 to other psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, SNPs revealed by GWASs likely lead to subtle changes in gene expression, in comparison to the large reductions in Btbd3 expression studied here in mice. Yet, risk genes for neuropsychiatric disorders identified by GWAS have been suggested to show an increased burden for rare variants with larger damaging effects102,103.

Our findings show that reduced Btbd3 expression induces compulsive-like behaviors and reduced exploration, phenotypes highly relevant to neuropsychiatric disorders including OCD. Furthermore, hippocampal Btbd3 expression plays an essential role in the regulation of these behaviors, but loss of BTBD3 in dorsal hippocampus is not sufficient to induce these effects. Future work will determine the molecular mechanisms and developmental time window in which Btbd3 expression confers these phenotypes. As any behavioral role of Btbd3 was previously unreported, our work highlights the importance of investigating unknown genes identified in an unbiased fashion104.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark Geyer and Richard Sharp for providing Night Owl software for spatial d analysis and assistance with its use. The authors would also like to thank Steven J. Thompson for providing technical assistance. This work was supported by a Brain Research Foundation seed grant (S.C.D.), a NARSAD Independent Investigator award (S.C.D.), R21-MH115395-01 (S.C.D.), Della Martin Foundation (J.A.K.), and training grants: T32 GM07839 (S.L.T.), and T32 DA07255 (S.L.T.).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-019-0558-7).

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

- 2.Brakoulias V, et al. Comorbidity, age of onset and suicidality in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): an international collaboration. Compr. Psychiatry. 2017;76:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillan, C. M., Kosinski, M., Whelan, R., Phelps, E. A. & Daw, N. D. Characterizing a psychiatric symptom dimension related to deficits in goal-directed control. eLife5, e11305 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Voon V, et al. Disorders of compulsivity: a common bias towards learning habits. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015;20:345–352. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins TW, Vaghi MM, Banca P. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: puzzles and prospects. Neuron. 2019;102:27–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruner P, Pittenger C. Cognitive inflexibility in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuroscience. 2017;345:243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollander, E. & Pallanti, S. Current and experimental therapeutics of OCD. in Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress: an Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (eds. Davis, K. L., Charney, D. S., Coyle, J. T. & Nemeroff, C.) 1647–1664 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002).

- 9.Korff S, Stein DJ, Harvey BH. Stereotypic behaviour in the deer mouse: pharmacological validation and relevance for obsessive compulsive disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;32:348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanahan NA, Velez LP, Masten VL, Dulawa SC. Essential role for orbitofrontal serotonin 1B receptors in obsessive-compulsive disorder-like behavior and serotonin reuptake inhibitor response in mice. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;70:1039–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanahan NA, et al. Chronic reductions in serotonin transporter function prevent 5-HT1B-induced behavioral effects in mice. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;65:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolmarans DW, Brand L, Stein DJ, Harvey BH. Reappraisal of spontaneous stereotypy in the deer mouse as an animal model of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): response to escitalopram treatment and basal serotonin transporter (SERT) density. Behav. Brain Res. 2013;256:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart SE, et al. Genome-wide association study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2013;18:788–798. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattheisen M, et al. Genome-wide association study in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCGAS. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015;20:337–344. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation Genetics Collaborative (IOCDF-GC) and OCD Collaborative Genetics Association Studies (OCGAS). Revealing the complex genetic architecture of obsessive-compulsive disorder using meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry23, 1181–1188 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Matsui A, et al. BTBD3 controls dendrite orientation toward active axons in mammalian neocortex. Science. 2013;342:1114–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1244505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lein ES, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–176. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller JA, et al. Transcriptional landscape of the prenatal human brain. Nature. 2014;508:199–206. doi: 10.1038/nature13185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langen M, Kas MJH, Staal WG, van Engeland H, Durston S. The neurobiology of repetitive behavior: of mice…. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011;35:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langen M, Durston S, Kas MJH, van Engeland H, Staal WG. The neurobiology of repetitive behavior: …and men. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011;35:356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saxena S, Rauch SL. Functional neuroimaging and the neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2000;23:563–586. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lapidus KAB, Stern ER, Berlin HA, Goodman WK. Neuromodulation for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11:485–495. doi: 10.1007/s13311-014-0287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradfield LA, Hart G, Balleine BW. The role of the anterior, mediodorsal, and parafascicular thalamus in instrumental conditioning. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2013;7:51. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2013.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson SAW, Horst NK, Pears A, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Role of the perigenual anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortex in contingency learning in the marmoset. Cereb. Cortex N. Y. N. 1991. 2016;26:3273–3284. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Meer M, Kurth-Nelson Z, Redish AD. Information processing in decision-making systems. Neurosci. Rev. J. Bringing Neurobiol. Neurol. Psychiatry. 2012;18:342–359. doi: 10.1177/1073858411435128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller KJ, Botvinick MM, Brody CD. Dorsal hippocampus contributes to model-based planning. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:1269–1276. doi: 10.1038/nn.4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parnaudeau S, et al. Mediodorsal thalamus hypofunction impairs flexible goal-directed behavior. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;77:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillan CM, et al. Disruption in the balance between goal-directed behavior and habit learning in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168:718–726. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10071062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillan CM, et al. Counterfactual processing of economic action-outcome alternatives in obsessive-compulsive disorder: further evidence of impaired goal-directed behavior. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;75:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillan CM, et al. Functional neuroimaging of avoidance habits in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2015;172:284–293. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14040525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gillan CM, Robbins TW. Goal-directed learning and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2014;369:20130475. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voon V, Reiter A, Sebold M, Groman S. Model-based control in dimensional psychiatry. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;82:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garner JP, Weisker SM, Dufour B, Mench JA. Barbering (fur and whisker trimming) by laboratory mice as a model of human trichotillomania and obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Comp. Med. 2004;54:216–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dulawa SC, Holick KA, Gundersen B, Hen R. Effects of chronic fluoxetine in animal models of anxiety and depression. Neuropsychopharmacol. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;29:1321–1330. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho EV, et al. Clinically effective OCD treatment prevents 5-HT1B receptor-induced repetitive behavior and striatal activation. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:57–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abudy A, Juven-Wetzler A, Zohar J. Pharmacological management of treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:585–596. doi: 10.2165/11587860-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leonard HL, et al. A double-blind desipramine substitution during long-term clomipramine treatment in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1991;48:922–927. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810340054007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinhardt V. Hair pulling: a review. Lab. Anim. 2005;39:361–369. doi: 10.1258/002367705774286448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eagle DM, Bari A, Robbins TW. The neuropsychopharmacology of action inhibition: cross-species translation of the stop-signal and go/no-go tasks. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:439–456. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richardson NR, Roberts DC. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1996;66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amitai N, et al. Isolation rearing effects on probabilistic learning and cognitive flexibility in rats. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;14:388–406. doi: 10.3758/s13415-013-0204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paulus MP, Geyer MA. A temporal and spatial scaling hypothesis for the behavioral effects of psychostimulants. Psychopharmacology. 1991;104:6–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02244547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adamah-Biassi EB, Hudson RL, Dubocovich ML. Genetic deletion of MT1 melatonin receptors alters spontaneous behavioral rhythms in male and female C57BL/6 mice. Horm. Behav. 2014;66:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deacon RMJ. Digging and marble burying in mice: simple methods for in vivo identification of biological impacts. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:122–124. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deacon RMJ, Rawlins JNP. Hippocampal lesions, species-typical behaviours and anxiety in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2005;156:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas A, et al. Marble burying reflects a repetitive and perseverative behavior more than novelty-induced anxiety. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:361–373. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1466-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Brouwer Geoffrey, Fick Arina, Harvey Brian H., Wolmarans De Wet. A critical inquiry into marble-burying as a preclinical screening paradigm of relevance for anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorder: Mapping the way forward. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;19(1):1–39. doi: 10.3758/s13415-018-00653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jirkof P. Burrowing and nest building behavior as indicators of well-being in mice. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2014;234:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deacon RMJ. Assessing nest building in mice. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1117–1119. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Misslin R, Belzung C, Vogel E. Behavioural validation of a light/dark choice procedure for testing anti-anxiety agents. Behav. Process. 1989;18:119–132. doi: 10.1016/S0376-6357(89)80010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dulawa SC, Hen R. Recent advances in animal models of chronic antidepressant effects: the novelty-induced hypophagia test. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005;29:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Porsolt RD, Anton G, Blavet N, Jalfre M. Behavioural despair in rats: a new model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1978;47:379–391. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McDonald, M. P. et al. Hyperactivity and learning deficits in transgenic mice bearing a human mutant thyroid hormone beta1 receptor gene. Learn. Mem. Cold Spring Harb. N 5, 289–301 (1998). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Hill RA, et al. Estrogen deficient male mice develop compulsive behavior. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;61:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kusunoki K, et al. Low novelty-seeking differentiates obsessive-compulsive disorder from major depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000;101:403–405. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101005403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyoo IK, Lee DW, Kim YS, Kong SW, Kwon JS. Patterns of temperament and character in subjects with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2001;62:637–641. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v62n0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kampman O, Viikki M, Järventausta K, Leinonen E. Meta-analysis of anxiety disorders and temperament. Neuropsychobiology. 2014;69:175–186. doi: 10.1159/000360738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alonso P, et al. Personality dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder: relation to clinical variables. Psychiatry Res. 2008;157:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heller HC, et al. Nest building is impaired in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome and rescued by blocking 5HT2a receptors. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2014;116:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeLorey TM, Sahbaie P, Hashemi E, Homanics GE, Clark JD. Gabrb3 gene deficient mice exhibit impaired social and exploratory behaviors, deficits in non-selective attention and hypoplasia of cerebellar vermal lobules: a potential model of autism spectrum disorder. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;187:207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carreno-Munoz MI, et al. Potential involvement of impaired BKCa channel function in sensory defensiveness and some behavioral disturbances induced by unfamiliar environment in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacol. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;43:492–502. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jager J, et al. Behavioral changes and dopaminergic dysregulation in mice lacking the nuclear receptor Rev-erbα. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014;28:490–498. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grant JE, et al. Trichotillomania and its clinical relationship to depression and anxiety. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2017;21:302–306. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2017.1314509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deacon RMJ, Croucher A, Rawlins JNP. Hippocampal cytotoxic lesion effects on species-typical behaviours in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2002;132:203–213. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garner JP, et al. Reverse-translational biomarker validation of abnormal repetitive behaviors in mice: an illustration of the 4P’s modeling approach. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;219:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Welch JM, et al. Cortico-striatal synaptic defects and OCD-like behaviors in SAPAP3 mutant mice. Nature. 2007;448:894–900. doi: 10.1038/nature06104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chamberlain SR, Fineberg NA, Blackwell AD, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Motor inhibition and cognitive flexibility in obsessive-compulsive disorder and trichotillomania. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:1282–1284. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nedeljkovic M, et al. Differences in neuropsychological performance between subtypes of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2009;43:216–226. doi: 10.1080/00048670802653273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vaghi MM, et al. Specific frontostriatal circuits for impaired cognitive flexibility and goal-directed planning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence from resting-state functional connectivity. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;81:708–717. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Altemus M, Glowa JR, Murphy DL. Attenuation of food-restriction-induced running by chronic fluoxetine treatment. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1993;29:397–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Altemus M, Glowa JR, Galliven E, Leong YM, Murphy DL. Effects of serotonergic agents on food-restriction-induced hyperactivity. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1996;53:123–131. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klenotich SJ, et al. Olanzapine, but not fluoxetine, treatment increases survival in activity-based anorexia in mice. Neuropsychopharmacol. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;37:1620–1631. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thompson, S. L. & Dulawa, S. C. Pharmacological and behavioral rodent models of OCD. in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Phenomenology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment (ed. Pittenger, C.) 385–400 (Oxford University Press, 2017).

- 74.Gillan CM, Otto AR, Phelps EA, Daw ND. Model-based learning protects against forming habits. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2015;15:523–536. doi: 10.3758/s13415-015-0347-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Brouwer Geoffrey, Fick Arina, Harvey Brian H., Wolmarans De Wet. A critical inquiry into marble-burying as a preclinical screening paradigm of relevance for anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorder: Mapping the way forward. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;19(1):1–39. doi: 10.3758/s13415-018-00653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li X, Morrow D, Witkin JM. Decreases in nestlet shredding of mice by serotonin uptake inhibitors: comparison with marble burying. Life Sci. 2006;78:1933–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jaramillo TC, et al. Novel Shank3 mutant exhibits behaviors with face validity for autism and altered striatal and hippocampal function. Autism Res. J. Int. Soc. Autism Res. 2017;10:42–65. doi: 10.1002/aur.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sungur AÖ, Vörckel KJ, Schwarting RKW, Wöhr M. Repetitive behaviors in the Shank1 knockout mouse model for autism spectrum disorder: developmental aspects and effects of social context. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2014;234:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wurzman R, Forcelli PA, Griffey CJ, Kromer LF. Repetitive grooming and sensorimotor abnormalities in an ephrin-A knockout model for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Behav. Brain Res. 2015;278:115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen JD, McClure SM, Yu AJ. Should I stay or should I go? How the human brain manages the trade-off between exploitation and exploration. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2007;362:933–942. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dulawa SC, Grandy DK, Low MJ, Paulus MP, Geyer MA. Dopamine D4 receptor-knock-out mice exhibit reduced exploration of novel stimuli. J. Neurosci. J. Soc. Neurosci. 1999;19:9550–9556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09550.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bodnoff SR, Suranyi-Cadotte B, Aitken DH, Quirion R, Meaney MJ. The effects of chronic antidepressant treatment in an animal model of anxiety. Psychopharmacology. 1988;95:298–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00181937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bowden CL, et al. Fluoxetine and desipramine in major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1993;13:305–311. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kleber RJ. A double-blind comparative study of desipramine hydrochloride and diazepam in the control of mixed anxiety/depression symptomatology. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1979;40:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2017;19:93–107. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.2/bbandelow. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nagarajan N, Jones BW, West PJ, Marc RE, Capecchi MR. Corticostriatal circuit defects in Hoxb8 mutant mice. Mol. Psychiatry. 2018;23:1–10. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shmelkov SV, et al. Slitrk5 deficiency impairs corticostriatal circuitry and leads to obsessive-compulsive-like behaviors in mice. Nat. Med. 2010;16:598–602. doi: 10.1038/nm.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Consortium TB, et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018;360:eaap8757. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Woehrle NS, Klenotich SJ, Jamnia N, Ho EV, Dulawa SC. Effects of chronic fluoxetine treatment on serotonin 1B receptor-induced deficits in delayed alternation. Psychopharmacology. 2013;227:545–551. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-2985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hein MY, et al. A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell. 2015;163:712–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sucic S, et al. The serotonin transporter is an exclusive client of the coat protein complex II (COPII) component SEC24C. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:16482–16490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.230037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.López-Murcia FJ, Royle SJ, Llobet A. Presynaptic clathrin levels are a limiting factor for synaptic transmission. J. Neurosci. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2014;34:8618–8629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5081-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Godsil BP, Kiss JP, Spedding M, Jay TM. The hippocampal–prefrontal pathway: The weak link in psychiatric disorders? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1165–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tseng KY, Chambers RA, Lipska BK. The neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion as a heuristic neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia. Behav. Brain Res. 2009;204:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lipska BK, Weinberger DR. Delayed effects of neonatal hippocampal damage on haloperidol-induced catalepsy and apomorphine-induced stereotypic behaviors in the rat. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1993;75:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lecourtier L, et al. Intact neurobehavioral development and dramatic impairments of procedural-like memory following neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion in rats. Neuroscience. 2012;207:110–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ouhaz Z, Ba-M’hamed S, Bennis M. Haloperidol treatment at pre-exposure phase reduces the disturbance of latent inhibition in rats with neonatal ventral hippocampus lesions. C. R. Biol. 2014;337:561–570. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Marquis J-P, Goulet S, Doré FY. Neonatal ventral hippocampus lesions disrupt extra-dimensional shift and alter dendritic spine density in the medial prefrontal cortex of juvenile rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2008;90:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Daenen EW, Van der Heyden JA, Kruse CG, Wolterink G, Van Ree JM. Adaptation and habituation to an open field and responses to various stressful events in animals with neonatal lesions in the amygdala or ventral hippocampus. Brain Res. 2001;918:153–165. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02987-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alvares GA, Balleine BW, Whittle L, Guastella AJ. Reduced goal-directed action control in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. J. Int. Soc. Autism Res. 2016;9:1285–1293. doi: 10.1002/aur.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vuijk R, de Nijs PFA, Vitale SG, Simons-Sprong M, Hengeveld MW. [Personality traits in adults with autism spectrum disorders measured by means of the Temperament and Character Inventory] Tijdschr. Voor Psychiatr. 2012;54:699–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sazonovs A, Barrett JC. Rare-variant studies to complement genome-wide association studies. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2018;19:97–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-083117-021641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Blair DR, et al. A nondegenerate code of deleterious variants in Mendelian loci contributes to complex disease risk. Cell. 2013;155:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stoeger T, Gerlach M, Morimoto RI, Amaral LAN. Large-scale investigation of the reasons why potentially important genes are ignored. PLOS Biol. 2018;16:e2006643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.