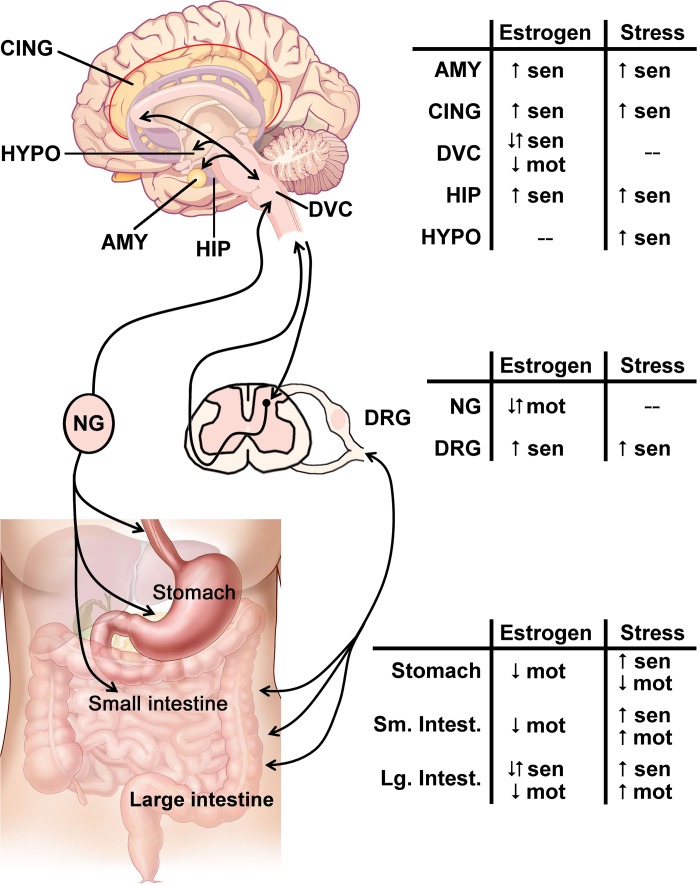

Fig. 1.

The effect of estrogen or stress in the brain-gut axis. The brain-gut axis, illustrated on the left, comprises bidirectional communication from the visceral organs to the brain via spinal and parasympathetic connections. Within the stress and pain responsive areas in the brain, such as the amygdala (AMY), cingulate cortex (CING), hippocampus (HIP), and hypothalamus (HYPO), integrate signals from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are transmitted through brainstem areas such as the dorsal vagal complex (DVC). The bidirectional communication is relayed and modified within parasympathetic ganglia, such as the nodose ganglia (NG), and/or sympathetic dorsal root ganglia (DRG), with further regulation of noxious signals within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Within the GI tract, the stomach and small intestine (Sm. Intest.) are primarily innervated by vagal afferents, whereas the majority of the large intestine (Lg. Intest.) is innervated by spinal afferents. For each region of the brain-gut axis, the summarized effect of estrogen signaling or stress on sensation (sen) or motility (mot) is indicated with up arrows (↑) for increased responses, down arrows (↓) for decreased responses, or both arrows (↑↓) when the response can both increase and decrease depending on the receptor subtype. Changes are measured compared with ovariectomized females for estrogen or nonstressed baselines for stress. A “−” indicates that there is no literature consensus on the effect at the listed region. Brain and GI images modified from CNX OpenStax/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-4.0. Available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Figure_35_03_06.jpg and https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GI_normal.jpg.