Abstract

It is important for the health care community to understand the impact of a child’s death on parent functioning. Yet involving bereaved parents in research that enquires about such a stressful time in their life can potentially bring harm to them. The current study examines the perceived benefit and burden of parents participating in a survey exploring their perceptions of their child’s end-of-life (EoL) and bereavement experiences. Parents whose child died from cancer or complications of cancer treatment were invited to complete a survey developed by pediatric psychosocial oncology professionals with input from bereaved parent advocates through a closed social media (Facebook) group. One hundred seventy-eight parents of children aged 0 to 37 years at death (median age 12 years) participated. More than three quarters of parents reported at least “a little benefit” and half reported at least “a little burden” associated with participation. Less burden was perceived by younger and female parents, parents of younger children, those who had felt prepared to meet their children’s emotional needs at EoL, and those not using bereavement services at the time of the survey. With the increasing use of social media as a source for bereaved parents to receive and provide emotional support, it is important for clinicians and researchers to understand the perceived benefits and risks of participating in research about EoL experiences via online recruitment. Our findings suggest that the benefit and burden of online research participation may vary for bereaved parents, but further research is necessary to replicate the findings and explore ways to optimize the use of this approach.

Keywords: childhood cancer, bereavement, end of life, benefit, burden

Children are expected to outlive their parents. The disruption in this natural order is a devastating experience for parents. It is important to understand how medical and psychosocial care at the end of a child’s life can improve to reduce complicated grief and additional trauma to parents following the death (Christ, Bonanno, Malkinson, & Rubin, 2003; Gilmer et al., 2012; Ginzburg, Geron, & Solomon, 2002). Yet involving bereaved parents in research that explores such a stressful time in their life can potentially bring increased risk.

Current literature is limited in its understanding of how bereaved parents perceive the benefit and burden associated with participation in research about their child’s end-of-life (EoL) experience (Olcese & Mack, 2012; Scott, Boyle, Bain, & Valery, 2002; Wiener, Battles, Zadeh, & Pao, 2015). In qualitative interviews with 64 bereaved parents in Norway, no parent regretted participating in the research, and all the participants found the experience to be “positive” or “very positive.” (100%, n = 64). Moreover, participation was reported to facilitate coping and increase awareness of the bereavement process. Although participation was reported as positive, 73% described their participation in the research interview as “painful” (Dyregrov, 2004). Similarly, bereaved parents in Australia described research interviews about their child’s death to be emotionally difficult but beneficial overall (Butler, Hall, & Copnell, 2018; Hynson et al., 2006). These studies included parents of children who had died from SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome), suicide, accidents (Dyregrov, 2004), and a variety of medical illnesses (Hynson et al., 2006). In the pediatric oncology parent population as well, perceived study burden has been reported to be low. In a series of six studies with bereaved parents of children with cancer (n = 210), which asked about EoL decision making, most of the bereaved parents denied experiencing distress during or after the study as a result of their participation (Hinds, Burghen, & Pritchard, 2007). Furthermore, although 19% of parents in one of the studies reported experiencing sad memories, none of them required professional assistance to address the memories (Hinds et al., 2007).

The largest study of bereaved parents of children who died of cancer (n = 432) was conducted via postal mail in Sweden between 1992 and 1997. The participants were asked about their children’s symptoms at EoL and about the quality of communication of the child’s medical team with the parents and the child. Parents’ mental health following the death of their child was explored. As part of the same study, the parents completed an additional questionnaire about their perceptions of the study experience, which was mailed back separately from the primary questionnaire to maintain anonymity. Almost all the participants (99%) described their study participation as valuable, with more than two thirds (68%) reporting that they were positively affected by their participation. Notably, more than one fourth (28%) of the participants reported that they were negatively affected, with 2% reporting being “very much” affected negatively (Kreicbergs, Valdimarsdottir, Steineck, & Henter, 2004).

Assessing the impact of research with bereaved parents that uses samples via a closed Internet support group is in its infancy. Available data suggest that web-based recruitment methods may be useful for recruiting diverse samples of childhood cancer caregivers (Akard, Wray, & Gilmer, 2015). Cultural and geographic diversity can be enhanced with recruitment through wider digital and online means. With the increasing use of the Internet and social media as a source for caregivers of children with cancer to receive and provide emotional support (Nagelhout et al., 2018), it is important for researchers to understand the impact of using such methods for data collection on bereaved parents. Although some caregivers may find benefit in sharing their story in person, others may prefer anonymity and find it easier to share through an online approach. To address this gap in knowledge, our primary aim was to explore the perceived benefit and burden associated with bereaved parents or caregivers (hereafter referred to only as “parents”) participating in an online survey to describe their child’s EoL experiences. Our secondary aim was to evaluate the benefit and burden by other sociodemographic characteristics including caregiver gender, age of child at the time of death, and bereavement service use.

Methods

Participants

Parents who self-identified as having lost their child to cancer were invited to complete a 46-item survey through a closed social media (Facebook) group (“Parents Who Lost Children to Cancer”). According to the Facebook administrator, the group included members from all 50 states of the United States and from Canada, Australia, the Philippines, and several European countries.

Procedures

With permission from the page administrator of the Facebook group, one of the Facebook group members posted a link to the survey along with an explanation about the study, including information regarding its purpose, intent, anonymity, voluntary nature, and intended study goals. Members of the group were asked not to share the link with other bereaved parents so as to ensure that data remained specific to those who have lost a child to cancer. No member of the research team was added to the Facebook group. The survey remained open for 3 months (March to June 2018). The group member sent three reminders in the form of posts to the Facebook group, with a link to the survey, 3 weeks apart for the first 2 months the study was open and once a week during the last month of the study to improve recruitment. Personal identifiers were not collected. Study approval was obtained from the National Institutes of Health Office of Human Subjects Research Protection, which determined that signed informed consent was not required.

Measures

The End-of-Life Preference Survey was a 47-item survey developed by pediatric psychosocial oncology professionals (psychologists, nurses, social workers, psychiatrists, oncologists) from multiple institutions with input from bereaved parent advocates. It contained assessments of support services provided throughout the child’s EoL care and perceived psychosocial needs of the child and family before, during, and after the child’s death to cancer. Participants were also asked via open- and closed-ended questions about their own communication with their child at EoL, whether they perceived their child to have suffered, the types of services provided by their child’s health care team, and opportunities for improvement for centers providing EoL support to families. Questions pertaining to the benefit and burden of research participation were the final items in the survey.

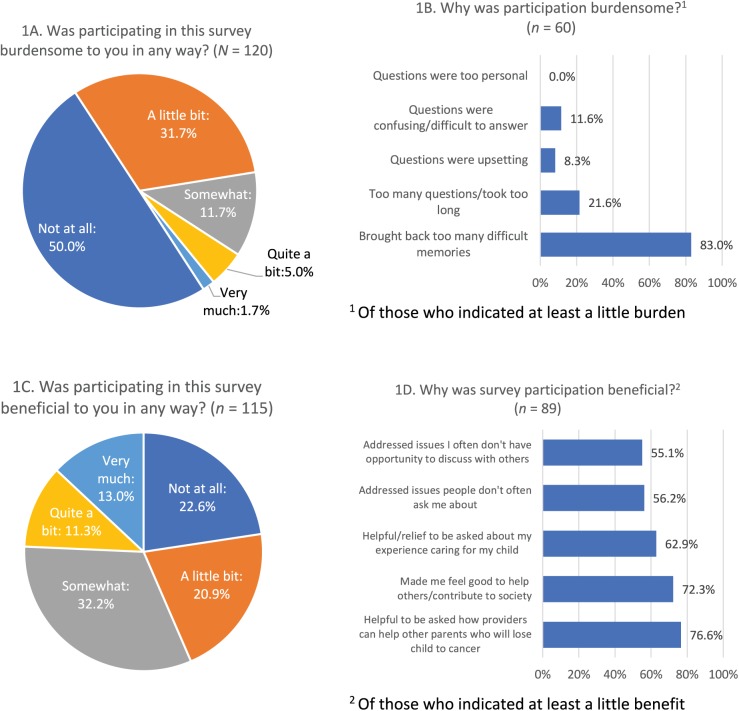

The Benefit and Burden Questionnaire (Pessin et al., 2008) was created for use with palliative care patients to assess the perceived benefit and burden of participating in a psychosocial study and was based on a prior literature review of patient-reported benefits and burdens of participating in palliative care research (Kristjanson, Hanson, & Balneaves, 1994). It uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4 and multiple-choice items as possible reasons for perceived benefit and burden. It was initially used as a brief self-report tool for patients themselves; the current study modified the four items to address bereaved parent participants. For example, responses for the multiple-choice question “Did you find it burdensome because . . . ” excluded responses that were irrelevant for the parent population, such as “I was too weak or too ill at times.” In addition, responses of particular relevance to the bereaved parent population were added, including “It brought back too many difficult memories.” The additional four questions and responses are included in Figure 1. Approximately two thirds of the participants (67.4%, n = 120) completed the questions pertaining to the extent to which participation in the study was burdensome, and 115 (64.6%) responded about the extent to which it was beneficial.

Figure 1.

Burden and benefit of study participation.

The entire survey was administered through SurveyMonkey, with branching logic directing participants to answer questions relevant to their respective experiences. The survey took the participants approximately 20 minutes to complete.

Data Analyses

Univariate statistics were used to describe the sample. Chi-square was used to describe the associations between benefit/burden and categorical variables (e.g., most demographic and EoL variables), and independent-sample t tests were used to describe the associations between benefit/burden and continuous variables (e.g., age). Analyses were conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), Version 21. Our sample of 120 yielded 62% power to detect a small effect size and 99% power to detect a medium effect size.

Results

Participants

One hundred and seventy-eight bereaved parents of children with cancer began the survey. There were no significant differences between those who began the survey and those who began the benefit/burden section in terms of parent age, child age at death, child’s cancer type, parent race, parent ethnicity, whether the child was ever in remission, length of time between child’s diagnosis and death, and place of child’s death. Men (54.5% vs. 72.4% of women, χ2[2, n = 120] = 5.3, p < .05) and parents with other children (65.3% vs. 100% of those without other children, n = 120, χ2 = 5.7, p < .05) were significantly less likely to have completed the benefit/burden section. For the remainder of this article, the analyses focus on the participants who completed the benefit/burden section (n = 120). Demographic characteristics of the final analytic sample are provided in Table 1. The children had a variety of diagnoses, and about half (52.5%, n = 63) had experienced at least one period of remission prior to death. Length of time from diagnosis to death ranged from under 1 year (24.2%, n = 29) to over 5 years (11.7%, n = 14). Approximately half of the children died at home (48.3%, n = 58).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 120).

| Characteristic | N | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 97 | 80.8 | ||

| Relationship to child | ||||

| Mother | 95 | 79.2 | ||

| Father | 23 | 19.2 | ||

| Grandparent | 2 | 1.6 | ||

| Has surviving child | 109 | 90.8 | ||

| Racea | ||||

| Caucasian | 113 | 94.2 | ||

| Non-Caucasian | 7 | 5.0 | ||

| Ethnicityb | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 3 | 2.5 | ||

| Not Hispanic/Latino/a | 106 | 88.3 | ||

| Unknown | 6 | 5.0 | ||

| Caregiver age (years)a | 48.9 | 8.0 | ||

| Child’s diagnosis | ||||

| Brain/spinal tumor | 37 | 30.8 | ||

| Blood cancer | 35 | 29.2 | ||

| Sarcoma | 32 | 26.7 | ||

| Neuroblastoma | 6 | 5.0 | ||

| Otherc | 10 | 8.3 | ||

| Time period between child’s diagnosis and death | ||||

| Under 1 year | 29 | 24.2 | ||

| 1-2 years | 46 | 38.3 | ||

| 3-5 years | 31 | 25.8 | ||

| Over 5 years | 14 | 11.7 | ||

| Child in remission prior to death | 63 | 52.5 | ||

| Child’s age at death (years) | 12.9 | 7.3 | ||

| Child’s place of deatha | ||||

| Home | 58 | 48.3 | ||

| Hospital | 53 | 44.2 | ||

| Hospice facility | 6 | 5.0 | ||

| Other | 3 | 2.5 | ||

n = 119. b n = 115. c Includes retinoblastoma, rhabdoid tumors, ovarian cancer, rectal cancer, duodenal cancer, thyroid cancer, epithelial parotid, Wilms tumor, and unknown.

More than three quarters of the participants were female (80.8%, n = 97) and the deceased child’s mother (79.2%, n = 95). Almost all the participants were Caucasian (94.2%, n = 113), and a small number (2.5%, n = 3) reported being of Hispanic or Latin ethnicity. The mean age of the respondents was 48.9 years (SD = 8.0) and ranged from 29 to 71 years. The median age of the child at death was 12 years (SD = 7.3) and ranged from 0.6 to 37 years.

Perceived Burden

Half of the participants (50.0%, n = 60) reported that taking part in the study was “not at all” burdensome. Less than 2% (1.7%, n = 2) found it to be “very” burdensome. Of those who reported any burden (n = 60), the most commonly endorsed explanation for the burden was that it “brought back too many difficult memories” (83.3%, n = 50). No one reported burden due to the questions being “too personal” (Figure 1).

Demographic Factors Associated With Burden

Male participants were more likely to report at least “a little burden” than women (73.9% vs. 44.3%; χ2[2, n = 120] = 6.5, p = .01), as well as older parents (61.1% of those over 50 years vs. 39.7% of those under 50 years; χ2[2, n = 115] = 5.1, p < .05). There were no significant associations between perceived burden of study participation and whether the participant had other children, and parent race or ethnicity.

EoL Factors Associated With Burden

Those who felt prepared to meet their child’s emotional needs during the EoL period were less likely to report perceived burden (35.7%) than those who were not prepared to meet their child’s needs (57.1%; χ2[2, n = 119] = 4.9, p = .05). Place of death (home or hospital) did not have a significant association with perceived burden of research participation (χ2[2, n = 120] = 7.6, p = .056), but the results trended toward less perceived burden for parents whose child died at home (no burden: 58.6%, n = 34; at least a little burden: 41.4%, n = 24) than for those whose child died in a hospital (no burden: 47.2%, n = 25; at least a little burden: 52.8%, n = 28). There were no significant associations between perceived burden of study participation and child age at death, child’s type of cancer, whether the caregiver felt prepared to meet the child’s medical needs at the time of death, length of time between diagnosis and death, whether the child was ever in remission, or whether the child had suffered at EoL.

Use of Bereavement Services Associated With Burden

Use of bereavement services was significantly associated with perceived burden (χ2[2, n = 119] = 5.3, p = .021). More participants who were using bereavement services at the time of the survey (57.0%, n = 49) considered study participation to be burdensome than nonusers (33.3%, n = 11).

Perceived Benefit

Almost three quarters of the caregivers (73.4%, n = 89) reported that survey participation was at least “a little bit” beneficial to them in some way. For those who found the study beneficial, the most commonly endorsed explanation was that “it was helpful to be asked about what health care providers can do to help other parents who will lose a child to cancer” (76.6%, n = 72). A similar majority reported an altruistic reason for benefit in study participation: “It made me feel good to help others/contribute to society” (72.3%, n = 68; Figure 1).

Demographic Factors Associated With Benefit

Caregivers of children who died at a younger age were significantly more likely to endorse benefiting from participating in this research (mean age 11.5 vs. 15.3 years; t[113] = 2.6, p = .01). Younger caregivers (under 50 years) were more likely to report benefit than older caregivers (87.5% vs. 64.7%; χ2[2, n = 115] = 7.7, p < .05). No significant differences in perceived benefit were found based on parent gender, whether the participant had other children, parent race or ethnicity, or type of cancer. A trend was found for females to report more benefit from study participation than males (80.4% vs. 65.2%), but this did not reach statistical significance (χ2[2, n = 115] = 2.4, p = .12).

EoL Factors Associated With Benefit

No significant difference was found between benefit and length of time between diagnosis and death, whether the child was ever in remission, how prepared caregivers felt to meet their children’s medical or emotional needs at EoL, or whether or not the child was perceived to have suffered at EoL.

Use of Bereavement Services Associated With Benefit

No significant difference was found between benefit and current use of bereavement services.

Discussion

Our study explored bereaved parents’ perceptions of benefit and burden while participating in a study about the care provided to their child at the end of his or her life as well as recommendations for when and how care should be provided to future families. Half of the bereaved parents found research participation at least “a little burdensome,” whereas nearly 75% found it at least a little beneficial. Burden and benefit varied based on several demographic and EoL factors.

In terms of burden, study participation reminded many parents of difficult and emotionally intense experiences with their child, yet they reported that enquiring about this time in their life was not “too personal.” Perceived burden was associated with gender, with a trend for more women to report benefit and significantly more men (comprising one grandfather and the remaining fathers) than women reporting at least “a little burden” from participating in this study. Past research has suggested that cancer-bereaved fathers may delay grieving and process grief less intuitively than mothers and that these gender differences may be due to sociocultural factors and individual differences in parenting bonds (Alam, Barrera, D’Agostino, Nicholas, & Schneiderman, 2012). These findings perhaps speak to a need for gender-sensitive language and research methods that pay attention to the similarities and differences between men and women’s experiences and viewpoints and give equal value to each.

Burden of study participation was not associated with the child’s age at death, the type of cancer, or how prepared parents felt to meet their child’s medical needs at EoL. Participants who were currently engaged with bereavement services reported higher levels of burden, possibly because those who access bereavement services are more distressed than those who do not use such services. A study of bereaved individuals, mainly spouses and children of deceased adult family members, found that individuals experiencing complicated grief were more likely to report that they may use bereavement services in the future (Banyasz, Weiskittle, Lorenz, Goodman, & Wells-Di Gregorio, 2017). Another study of bereaved spouses found that depressive symptoms, as well as anxiety and grief, are related to increased use of bereavement services (Bergman, Haley, & Small, 2010). In the context of the current study, it is possible that parents currently engaged with bereavement services are also those who experience the most bereavement-related distress, thus explaining why bereavement service users more commonly reported burden.

More burden was also reported for parents who felt less prepared to meet their child’s emotional needs during the EoL period. Whether other unmeasured variables such as family communication or specific symptoms at the time of the child’s death could explain these associations is not known. One could also speculate that parents join an online support group for emotional support and encountering a survey on a painful issue, such as events that occurred at the end of their child’s life, may have contributed to the burden associated with study participation. Additionally, it is not known whether specific questions might have triggered a sense of burden. Researchers could benefit from a better understanding of the characteristics of bereaved parents that might be related to increased perception of burden or harm in participation.

Most of the participants found benefit in their study participation, particularly for altruistic reasons. The desire of bereaved parents to help others and improve the experiences of families in the future has been noted in past and present research (Butler et al., 2018; Hynson et al., 2006), postulating that such experiences can be helpful in facilitating the grief process (Dyregrov, 2004). Bereaved parents have described feeling relieved when asked about difficult times and experiences (Weaver et al., 2018). Despite experiencing higher levels of burden, two thirds of the male parents reported benefit from participating in this study. High levels of benefit finding in terms of personal growth, spiritual change, and relationships with others have been found in fathers after the diagnosis of their child’s cancer (Hensler, Katz, Wiener, Berkow, & Madan-Swain, 2013). These data suggest that perceived burden and benefit are not necessarily the ends of a continuum and that finding an appropriate balance may be most important in determining the overall experience of research participation for parents.

Younger child and parent age were also associated with greater perceived benefit. Younger parents are more frequent Internet users and more likely to use social media to consume parenting information than older parents (Baker, Sanders, & Morawska, 2017). Thus, the younger parents in our study may have perceived greater benefit because they perceive the Internet and social media–based support as more useful than older parents. Parents who are grieving the loss of a younger child may have a greater need to find meaning in their young child’s life. It is also possible that younger children require full advocacy from their parents whereas older children or adolescents are better able to speak to their own experience and suffering, which can empower the family to transition more confidently to an EoL and comfort approach. Benefit was not related to cancer type, parent preparation for the child’s medical or emotional needs at EoL, or current use of bereavement services.

This study has a number of limitations. Only members of this closed Facebook support group for parents who had lost a child to cancer had access to the survey, introducing ascertainment bias. Participants had to have access to social media/computers and be able to read and write in English. As in other studies with parents of children with cancer, there was limited racial/ethnic and gender diversity in the sample. As questions about state or country of residence were not included, we do not know the degree of geographic diversity of our sample. The survey also did not ask how recent was the death of the child, which may influence the levels of perceived benefit and burden for participants. It was not possible to determine the response rate to the study, as data on how many members of the Facebook group signed onto the site the days the study was open were not available. Last, some participants skipped questions or elected to end their participation before reaching the final question in the survey, and their reasons for doing so are unknown. Although this study was not designed to assess the impact of a closed Internet group on recruitment, online recruitment was a potential strength of the study as it provided an opportunity to learn from and discover new information from hard to reach populations. Future research would benefit from the inclusion of comparison samples of groups recruited using standard methods. Having a standardized method to determine the benefit–risk ratio for research with bereaved parents could also advance the field.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the benefits and burdens of participating in research about EoL experiences via online recruitment of bereaved parents whose child died from cancer. Strengths of the study included the use of psychosocial experts and bereaved parents for the development and review of the survey prior to administration, recruitment through a novel method, and a diverse sample in terms of parent and child age, length of cancer treatment, and cancer diagnosis, which provided a breadth of experience to contribute to the knowledge base on the benefit and burden of bereavement research participation. Although some burden was endorsed by half of the participants, many also expressed benefit, particularly in the matter of feeling good about helping others or being asked about what health care providers can do to help other parents who will lose a child to cancer. These findings suggest that perceived benefits could outweigh risks when both are present. The results may inform current psychosocial research practices in palliative care and bereavement, particularly in solidifying the evidence that research with bereaved parents is not exclusively burdensome or without merits for participants. Although further research is needed to replicate and further explore these findings, social media may be an effective way to reach this often overlooked and vulnerable population. Clinicians and researchers should remain mindful of the variability in perceptions of participation. Strategies to reduce the perceived burden of research participation for men, parents of older children, and those engaged in bereavement care are needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Peter Brown for his leadership in making this survey possible. We greatly appreciate the guidance and wisdom provided by Victoria Sardi-Brown, PhD, in the construction of the survey. We are also grateful to Dr. Justin Baker and parents on the St. Jude Bereaved Parent Steering Council for reviewing and assisting in framing the key questions and wording used in the survey.

Author Biographies

Julia Tager, BA, is an assistant laboratory manager in the Affect and Social Cognition Lab at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in Amherst, MA.

Haven Battles, PhD, is a social psychologist and research associate in the Behavioral Science Core of the Pediatric Oncology Branch of the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD.

Sima Zadeh Bedoya, PsyD, is a pediatric psychologist in the Behavioral Science Core of the Pediatric Oncology Branch of the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD.

Cynthia A. Gerhardt, PhD, is an associate professor of Pediatrics and Psychology at The Ohio State University and director of the Center for Biobehavioral Health at the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH.

Tammi Young-Saleme, PhD, is a clinical professor of Pediatrics at The Ohio State University and director psychosocial services and program development in the Hematology/Oncology BMT division at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH.

Lori Wiener, PhD, is co-director of the Behavioral Science Core and Head, Psychosocial Support and Research Program in the Pediatric Oncology Branch of the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iD: Lori Wiener  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9573-8870

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9573-8870

References

- Akard T. F., Wray S., Gilmer M. (2015). Facebook ads recruit parents of children with cancer for an online survey of web-based research preferences. Cancer Nursing, 38, 155. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam R., Barrera M., D’Agostino N., Nicholas D. B., Schneiderman G. (2012). Bereavement experiences of mothers and fathers over time after the death of a child due to cancer. Death Studies, 36(1), 1-22. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2011.553312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S., Sanders M., Morawska A. (2017). Who uses online parenting support? A cross-sectional survey exploring Australian parents’ Internet use for parenting. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 26(3), 916-927. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0608-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banyasz A., Weiskittle R., Lorenz A., Goodman L., Wells-Di Gregorio S. (2017). Bereavement service preferences of surviving family members: Variation among next of kin with depression and complicated grief. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20, 1091-1097. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman E. J., Haley W. E., Small B. J. (2010). The role of grief, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in the use of bereavement services. Death Studies, 34, 441-458. doi: 10.1080/07481181003697746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A. E., Hall H., Copnell B. (2018). Bereaved parents’ experiences of research participation. BMC Palliative Care, 17, 122. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0375-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ G. H., Bonanno G., Malkinson R., Rubin S. (2003). Appendix E: Bereavement experiences after the death of a child. In Field M. J., Behrman R. R. (Eds.), When children die: Improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families (pp. 553-579). Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyregrov K. (2004). Bereaved parents’ experience of research participation. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 391-400. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00205-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer M. J., Foster T. L., Vannatta K., Barrera M., Davies B., Dietrich M. S., . . . Gerhardt C. A. (2012). Changes in parents after the death of a child from cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 44, 572-582. doi: 10.1016/2Fj.jpainsymman.2011.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzburg K., Geron Y., Solomon Z. (2002). Patterns of complicated grief among bereaved parents. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 45, 119-132. doi: 10.2190/2FXUW5-QGQ9-KCB8-K6WW [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hensler M., Katz E. R., Wiener L., Berkow R., Madan-Swain A. (2013). Benefit finding in fathers of childhood cancer survivors: A retrospective pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 30, 161-168. doi: 10.1177/1043454213487435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds P. S., Burghen E. A., Pritchard M. (2007). Conducting end-of-life studies in pediatric oncology. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 29, 448-465. doi: 10.1177/0193945906295533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynson J. L., Aroni R., Bauld C., Sawyer S. M. (2006). Research with bereaved parents: A question of how not why. Palliative Medicine, 20, 805–811. Retrieved from 10.1177/0269216306072349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdottir U., Steineck G., Henter J. (2004). A population-based nationwide study of parents’ perceptions of a questionnaire on their child’s death due to cancer. Lancet, 364, 787-789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16939-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanson L. J., Hanson E. J., Balneaves L. (1994). Research in palliative care populations: Ethical issues. Journal of Palliative Care, 10, 10-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhout E. S., Linder L. A., Austin T., Parsons B. G., Scott B., Gardner E., . . . Wu Y. P. (2018). Social media use among parents and caregivers of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 35, 399-405. doi: 10.1177/1043454218795091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcese M. E., Mack J. W. (2012) Research participation experiences of parents of children with cancer who were asked about their child’s prognosis. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15, 269-273. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessin H., Galietta M., Nelson C., Brescia R., Rosenfeld B., Breitbart W. (2008). Burden and benefit of psychosocial research at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11, 627-632. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.9923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. A., Boyle F. M., Bain C. J., Valery P. C. (2002). Does research into sensitive areas do harm? Experiences of research participation after a child’s diagnosis with Ewing’s sarcoma. Medical Journal of Australia, 177, 507-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L., Battles H., Zadeh S., Pao M. (2015). Assessing the experience of medically ill youth participating in psychological research: Benefit, burden, or both? IRB, 37(6), 1-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver M. S., Bell C. J., Diver J. L., Jacobs S., Lyon M. E., Mooney-Doyle K., . . . Hinds P. S. (2018). Surprised by benefit in pediatric palliative care research. Cancer Nursing, 41, 86-87. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]