Abstract

Atomoxetine (ATX) is a non-stimulant drug used in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. It has been shown that ATX has additional effects beyond the inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake, affecting several signal transduction pathways and alters gene expression. Here, we study alterations in oxidative stress and mitochondrial function in human differentiated SH-SY5Y cells exposed over a range of concentrations of ATX. We found that the highest concentrations of ATX in neuron-like cells, caused cell death and an increase in cytosolic and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, and alterations in mitochondrial mass, membrane potential and autophagy. Interestingly, the dose of 10 μM ATX increased mitochondrial mass and decreased autophagy, despite the induction of cytosolic and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Thus, ATX has a dual effect depending on the dose used, indicating that ATX produces additional active therapeutic effects on oxidative stress and on mitochondrial function beyond the inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake.

Subject terms: Cell death in the nervous system, Cellular neuroscience

Introduction

Increased hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention are the main features of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which is a neurobehavioral disorder in children1,2. The pathophysiology of ADHD is not completely understood, but has been associated with deregulation of the catecholaminergic pathway in the brain3, although some findings show that the pathophysiology of ADHD is associated with oxidative stress4–6. Regarding this, elevated levels of malondialdehyde, which is a marker of lipid peroxidation, were found in children and adults with ADHD7–9. Also, an oxidative imbalance was demonstrated in children and adults with ADHD7,10. Moreover, in a extensively accepted rat model of ADHD, spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) showed an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the striatum, hippocampus and cortex11.

Atomoxetine (ATX) is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and is a non-stimulant which has been approved for the treatment of ADHD due to its clinical efficacy in reducing ADHD symptoms and by increasing the quality of life12. ATX has gained interest as a first-line therapy for ADHD, as it has no known effect on drug abuse-related brain regions13. Thus, the administration of ATX increased extracellular norephinephrine and dopamine levels in the occipital cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and hypothalamus of rats12,14,15. Also, ATX binds selectively to the presynaptic norephinephrine transporter, with a little affinity for other neurotransmitters receptors or transporters12,15. However, there is a limited knowledge of mitochondrial alterations resulting from the therapeutic effects of ATX. Accordingly, it has been shown that ATX has additional effects beyond norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, altering gene expression and affecting several signal transduction pathways. In the SHR model, ATX up-regulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression in the prefrontal cortex, thus resulting beneficial for cognition and cellular plasticity16. Also, it was demonstrated that clinically relevant concentrations of ATX in cortical and hippocampal neurons from rats acted as an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blocker17, correlating the findings of altered glutamatergic transmission observed in ADHD18,19. ATX inhibits G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK), particularly brain- and cardiac-type GIRK channels, which may influence synaptic transmission and neuronal excitability20. Another report indicated that in the prefrontal cortex of young rats, ATX induced an increase in the expression of the ubiquinol–cytochrome c reductase complex core protein 2, as well as an increase in the GABA A receptor subunit, and in the synaptosomal-associated protein of 25 kDa, which is a membrane protein involved in synaptic vesicle exocytosis, fundamental for the synaptic transmission21. Recently, it was demonstrated that ATX inhibited NMDA receptors in clinically relevant micromolar concentrations and displayed voltage- and magnesium-dependent open channel blocking mechanisms in rat brain neurons22. The acid-sensing ion channels open in response to extracellular acidification, are widely distributed in the CNS and play a modulatory role and contribute to memory, learning processes and synaptic plasticity. Thus, ATX was demonstrated to potentiate acid-sensing ion channel response in rat brain neurons23.

The effects of ATX on the generation of oxidative stress and mitochondrial function have not been investigated so far. Therefore, in the present study, we evaluate whether ATX has an impact on oxidative stress and mitochondrial function in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, differentiated into neuron-like cells.

Results

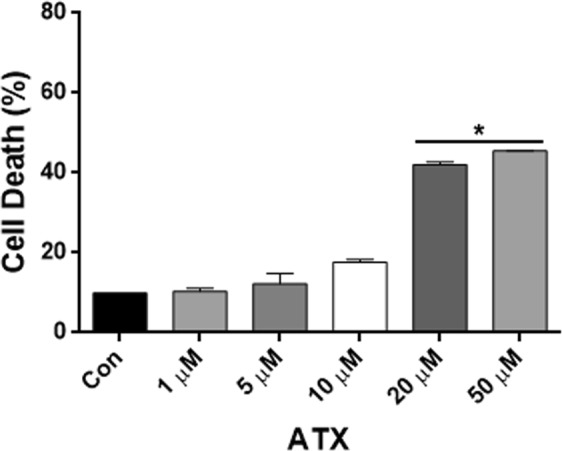

ATX induced cell death in human neuron-like cells

We carried out experiments to explore the effect of ATX over a range of concentrations on the neuron-like cells over 7 days of treatment. Figure 1 shows the percentage of cell death with a range from 1 to 50 μM of ATX. ATX exhibited a significant increase in cell death at concentrations between 20 and 50 μM (32 and 35%), while the treatment with doses 1, 5 and 10 μM produced between 1, 1.2 and 7.7% cell death, respectively, compared to control cells. In order to investigate if the cell death induced by the highest concentrations of ATX may be mediated by the generation of ROS, we analysed whether antioxidant supplementation with ascorbic acid might attenuate the effect induced by ATX. Exposure during the differentiation of cells to ascorbic acid (50 μM) alone for 7 days did not alter the cell viability (Supplementary Fig. S1). The co-treatment of cells with ascorbic acid (50 μM) and with the highest concentrations of ATX for 7 days attenuated the cell death induced by ATX (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

ATX induced cell death in human neuron-like cells. Cells were untreated (con) and treated with ATX for 7 days at different doses (1, 5, 10, 20 and 50 μM). Percentage of cell death at different concentrations of ATX. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group.

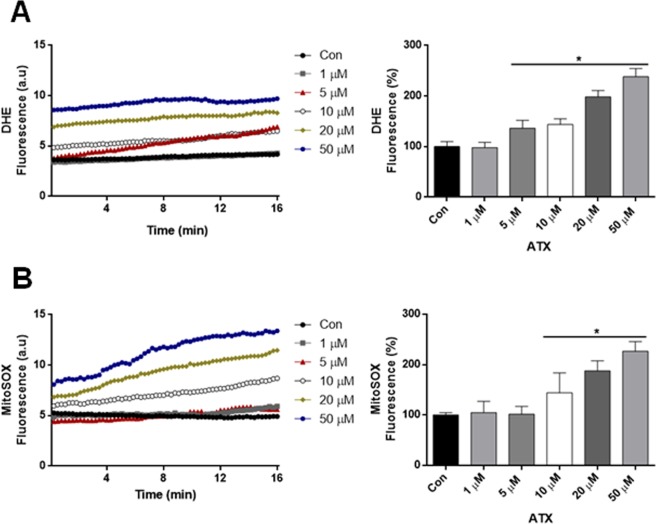

ATX treatment increased the rate of cytosolic and mitochondrial ROS in human neuron-like cells

We evaluated the effect of ATX upon the generation of cytosolic and mitochondrial ROS with the different concentrations of ATX. Cytosolic ROS production was measured with dihydroethidine (DHE). Cytosolic ROS production was increased significantly in neuron-like cells treated with ATX during 7 days in comparison with control cells (Fig. 2A), while the ROS generation was not significant with 1 μM of ATX. Similar results were observed using MitoSOX, where mitochondrial ROS production was increased significantly in neuron-like cells that were treated with 10, 20 and 50 μM; also, with the lower concentrations, there were no significant increases (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

ATX treatment increased the rate of cytosolic and mitochondrial ROS in human neuron-like cells. (A) The increase in cytosolic ROS production in cells treated with ATX during 7 days. The quantification values of the rate of change of DHE fluorescence are shown in bar graph. (B) The increase in mitochondrial ROS production in cells treated with ATX. The quantification values of the rate of change of MitoSOX fluorescence are shown in a bar graph. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group.

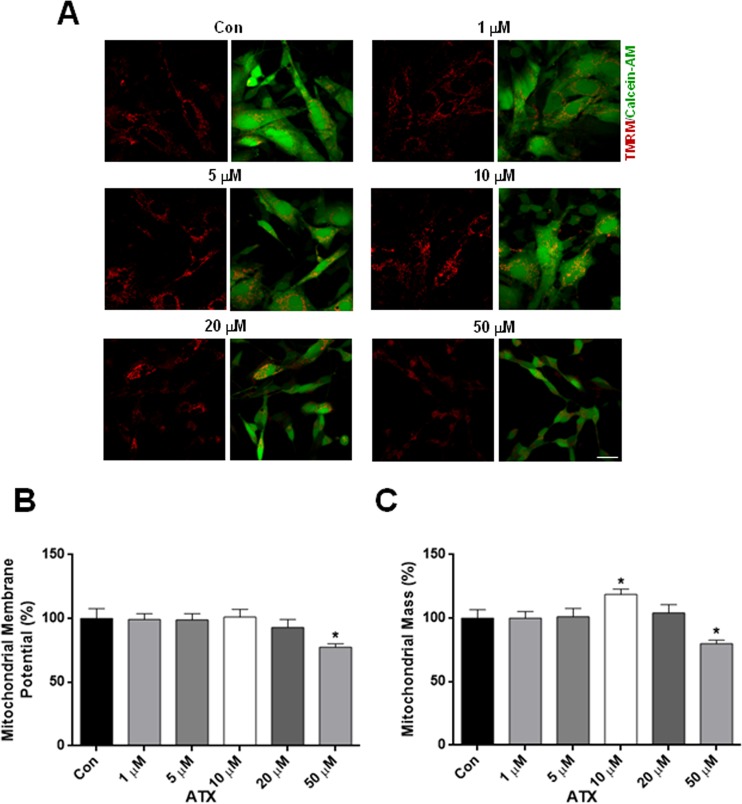

Effects of ATX on mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and mass in human neuron-like cells

We further evaluated mitochondrial alterations in response to ATX treatment. Neuron-like cells were loaded with TMRM to determine changes in ΔΨm. Figure 3A shows representative confocal images taken from neuron-like cells treated with the different concentrations, quantified in Fig. 3B. The treatment of neuron-like cells at 50 μM of ATX for 7 days caused a significant decrease of ΔΨm (Fig. 3B), showing that ATX induces mitochondrial dysfunction. In order to measure mitochondrial mass, neuron-like cells were co-loaded with calcein-AM to label the cytosol and with TMRM to label mitochondria (Fig. 3C). Seven days of treatment with 50 μM of ATX induced a significant decrease in mitochondrial mass, which was not observed with 1, 5, 20 μM of ATX or in control cells (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, the dose of 10 μM of ATX induced a significant increase in mitochondrial mass above that which is seen in control cells (Fig. 3C). Together these findings show that ATX has a dual effect depending on the dose used, as demonstrated by the increase in mitochondrial mass at 10 μM or by the decrease in the ΔΨm and mass with the higher concentration.

Figure 3.

ATX altered ΔΨm and mass in human neuron-like cells. (A) Representative confocal images of ΔΨm, were measured by the retention of TMRM (red) and mitochondrial mass which was calculated from the images using calcein-AM (green) to define the cytosol. (B) Quantification of ΔΨm and (C) mitochondrial mass. Data are mean ± SEM, and values are from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group. Scale bar = 10 μm.

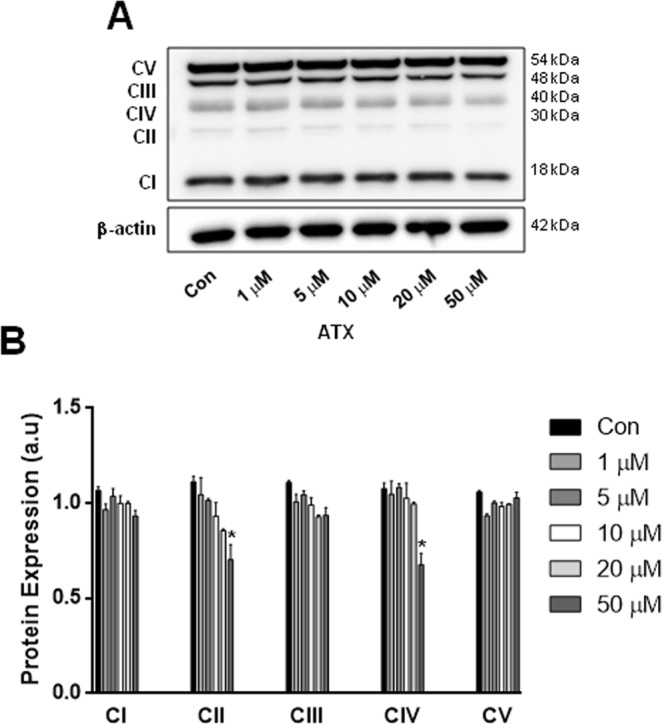

ATX altered mitochondrial OxPhos complexes

To evaluate whether mitochondrial OxPhos complexes were altered in the ATX-treated neuron-like cells, we analysed protein levels using Western blotting with a total OxPhos complex kit. Figure 4A,B revealed that ATX caused a decrease in protein contents of mitochondrial Complex II and Complex IV with 50 μM of ATX. However, there were no significant alterations in the protein contents of the other OxPhos complexes (Complexes I, III, and V), using the other concentrations of ATX when compared to control cells. This confirms that the higher concentration of ATX induced mitochondrial dysfunction.

Figure 4.

ATX altered mitochondrial OxPhos complexes. (A) Representative western blot. (B) Quantification of western blot analysis of mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes in neuron-like cells treated with different concentrations of ATX. β-actin was used as a loading control. Data are mean ± SEM, and values are from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group. For clarity of the results, the representative Western blots are cropped, for raw data see Supplementary Information.

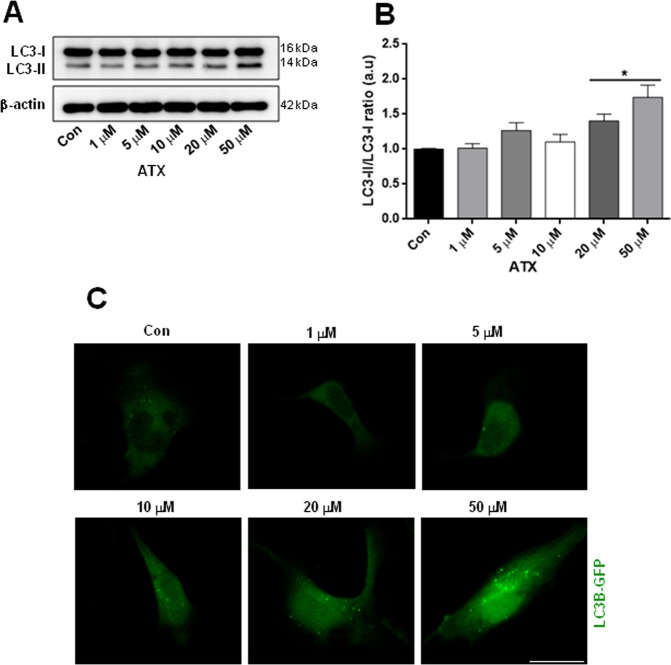

ATX induced alterations in autophagy in neuron-like cells

To evaluate the role of autophagy after ATX treatment, we investigated whether autophagy is altered by the different concentrations of ATX. Autophagy was assessed using Western blot analysis of the ratio of LC3II-LC3I and to corroborate our results of western blot, we decided to use a qualitative method for which we used confocal microscopy to explore the translocation of LC3B-GFP to form puncta. Western blotting demonstrated an increased autophagy induced by the doses of 20 and 50 μM of ATX, showing a significant increase in the ratio of LC3-II/I or in the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II (Fig. 5A,B) compared to control cells. Interestingly, the treatment of neuron-like cells with 10 μM of ATX decreased the ratio of LC3-II/I (Fig. 5B), almost back to control levels. Moreover, confocal images confirmed that the autophagosome formation was significantly increased in neuron-like cells treated with 20 and 50 μM of ATX (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these findings confirm that ATX has a dual effect, as demonstrated by the autophagy alterations, correlating the effect that ATX had on mitochondrial mass with the same doses.

Figure 5.

ATX induces alterations on autophagy in neuron-like cells. (A) Representative western blots and (B) quantification analysis of LC3-II levels. β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) Representative confocal images showed the LC3B-GFP puncta formation with different concentrations of ATX. Data are mean ± SEM, and values are from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group. Scale bar = 10 μm. For clarity of the results, the representative Western blots and confocal images are cropped, for raw data see Supplementary Information.

Discussion

The catecholamines (dopamine and norepinephrine) are neurotransmitters in the central nervous system: nevertheless, dopamine and norepinephrine can easily undergo auto-oxidation forming ROS24–26. Therefore, reaction products formed by the oxidation of catecholamines result in cell damage and damage to DNA27,28. It has been shown that norepinephrine can be either damaging or protective to cells, depending on the norepinephrine concentration and cell type29–31. Thereby, low levels of norepinephrine were shown to protect dopaminergic neurons32. Moreover, norepinephrine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and downregulation of norepinephrine transporter density in PC12 cells were via oxidative stress33. It was demonstrated that dopamine-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells, via extracellular auto-oxidation of dopamine and consequent oxidative stress, also it was demonstrated that ascorbic acid effectively blocked the toxic effects of dopamine, suggesting that extracellular auto-oxidation of dopamine is responsible for the oxidative stress34. As mentioned above, ATX is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that increases extracellular norephinephrine and dopamine levels12,15. The excessive accumulation of extracellular norepinephrine due to the action of a high concentration of ATX could mean that norepinephrine undergoes auto-oxidation and initiates several events such as ROS generation, which would generate cell damage, affecting mitochondrial function.

We showed that the highest concentrations of ATX increased the rate of cytosolic and mitochondrial ROS in human neuron-like cells (Fig. 2), and as a consequence produced cell death (Fig. 1). Also, we demonstrated that the co-treatment of cells with ascorbic acid plus the highest concentrations of ATX for 7 days, attenuated the cell death induced by ATX (Supplementary Fig. S1). Thus, demonstrating that ascorbic acid, which is an antioxidant is capable to protect the cells against oxidative stress, attenuating the cell death, due to its scavenger capacity with extracellular and intracellular ROS species as demonstrated previously35,36. This is supported by the fact that ATX increased ROS (superoxide levels) in T-lymphocytes and caused a dose-dependent decrease in cell number37. Also, the effects of ATX on development of the brain have been reported in rats, where ATX might have neurotoxic effects; this has been demonstrated by neurodegenerative effects on the cerebellum and hippocampus. Thus, the authors suggest that ATX neurotoxicity may arise as a result of ROS formation due to catecholamine oxidation38. The psychostimulant methylphenidate (MPH) is the first choice of treatment for ADHD, increasing extracellular dopamine and norepinephrine levels in the brain39. Hence, the acute and chronic use of MPH in adult SHR increased oxidative stress and induced energetic metabolism alterations40. The maintenance of ΔΨm is an important factor for cell health; therefore, a decrease in ΔΨm will result in mitochondrial dysfunction. The decrease in ΔΨm and the decrease in mitochondrial complexes II and IV were alterations found in response to ATX treatment, suggesting that ATX treatment causes a damage to mitochondrial function at the highest concentration used. Accordingly, mitochondrial defects can also lead to ROS generation41,42.

Disturbances in mitochondrial homeostasis may result from impaired balance in the pathways that promote mitochondrial repair (biogenesis) and pathways that remove dysfunctional mitochondria (mitophagy); the impaired coordination between both processes is a feature of several neurodegenerative disorders43. The observed dual or biphasic response with different doses of ATX in mitochondrial mass suggests either increased or decreased removal by autophagy. Autophagy is crucial for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis in physiological conditions because it mediates the removal of dangerous constituents such as damaged organelles, proteins and dysfunctional mitochondria; however, its role in cell death and survival remains controversial. For example, autophagy is up-regulated when cells need to generate intracellular nutrients and energy, such as starvation or high bioenergetic demands and is also up-regulated during oxidative stress, which allows cells to survive; in contrast, deregulated or insufficient autophagy can promote cell damage44,45. Using Western blotting and a fluorescent autophagosome marker, LC3B-GFP, we found that ATX at the highest concentrations induced an increase in autophagy in neuron-like cells, while 10 μM ATX decreased the levels of autophagy. Thus, the biphasic response to autophagy appears to be essential to the changes in mitochondrial mass associated with 10 μM ATX treatment. In that sense, it was demonstrated that ATX used at a lower dose was effective in the prevention of skeletal muscle atrophy in a model of dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy, by sustaining PGC1α expression; PGC1α is a transcriptional co-activator that regulates mitochondrial biogenesis46. Also, treatment with lower doses of ATX significantly attenuated the cognitive deficits in post-traumatic injured rats47,48. Moreover, mitochondrial ROS generation depends on mitochondrial metabolism and may constitute the mechanism by which damaged mitochondria are selectively targeted for autophagic removal. We found that the highest concentrations of ATX increased ROS production and autophagy in neuron-like cells, but there were no such effects at lower concentrations.

Therefore, the biphasic response by ATX in neuron-like cells may be mediated by the dose and trigger of several mechanisms, including oxidative stress and autophagy. Mitophagy can be triggered by increased ROS generation41,49,50. Methamphetamine is a psychostimulant used for the treatment of ADHD which induces the release of dopamine from vesicles to the cytosolic and extracellular space, resulting in neurotoxicity51. Thus, the neurodegeneration of dopaminergic neurons induced by methamphetamine has been shown to increase autophagy52. Also, methamphetamine induces a decrease in ΔΨm, a decrease in mtDNA copy number and an increase in ROS levels. Furthermore, the use of vitamin E attenuated cell death and an increase in intracellular ROS levels induced by methamphetamine53. Therefore, it has been demonstrated that enhanced antioxidant defences, ROS scavengers or the overexpression of antioxidants reduced levels of autophagy41,49,54.

Regarding the pharmacokinetics and the effective concentrations in vivo, it has been demonstrated that ATX is metabolized through the cytochrome P-450 2D6 enzyme pathway, which is polymorphic in humans, leading to a bimodal distribution of the pharmacokinetics; divided into poor metabolizers (7% Caucasians) and extensive metabolizers. In children and adolescent with ADHD, a study evaluated the pharmacokinetics of ATX, Cmax detected ranged from 80 to 212 ng/ml with 10 mg dose55. A twice-daily dose 20–45 mg of ATX, Cmax detected ranged from 174 to 1221 ng/ml, which means that the latter concentration close to 5 μM. Thus, the total plasma exposure in poor metabolizers of ATX is approximately 10-fold higher when compared with extensive metabolizers56. Lempp et al. in the prefrontal cortex of rats, adjusted the dosing procedure closely resemble the clinical paediatric treatment (oral administration, once daily, long-term application), obtained a Cmax 139 ± 17 ng/ml, according with the data published by Witcher et al.21,55. A microdialysis study in rats demonstrated a high brain penetration of ATX concentration in brain cells higher than in plasma57. Thus, plasma concentrations of ATX are in the micromolar range. Besides, it was demonstrated that ATX blocked NMDA receptor in the micromolar range17.

Finally, as mentioned before, it has been shown that ATX has additional effects, affecting several signal transduction pathways and altering gene expression16,17,20,21; for that reason, it is necessary to add the effects on the oxidative stress and on mitochondrial function as demonstrated here.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that treatment with the highest concentration of ATX in neuron-like cells caused mitochondrial alterations, enhanced oxidative stress, disturbed mitochondrial mass and autophagy, indicating that ATX activated these events in a consecutive manner. The enhanced oxidative stress might trigger alterations in ΔΨm and aberrant mitochondrial biogenesis, which results in a decrease in mitochondrial mass and an increase in autophagy after ATX treatment. Dysfunctions in the mitochondria are a source of ROS; therefore, mitochondrial alterations might provide a sequence of mechanisms by which ATX induces more oxidative stress and increases cell death. As a consequence, additional studies are required to characterise the dose of ATX and to determine a window of time and concentration in which the ATX, beyond being harmful, can be beneficial, especially for patients who use this drug for the treatment of ADHD. This is because we found that 10 μM of ATX had a positive effect, as demonstrated by the increase in mitochondrial mass and the decrease in autophagy, at least in our conditions and in our cell model. Therefore, ATX has a biphasic response depending on the dose used, indicating that ATX produces additional active therapeutic effects on oxidative stress and on mitochondrial function beyond the inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake.

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

DMEM, F12, foetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin, total OxPhos complex kit, Tetramethylrhodaminemethyl ester (TMRM), calcein-AM, Premo™ Autophagy Sensor LC3B-GFP, MitoSOX and Dihydroethidine (DHE) were obtained from Molecular probes-Invitrogen. Atomoxetine hydrochloride (ATX), ascorbic acid, retinoic acid, MTT and dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The β-actin antibody (1:1000) and the LDH-cytotoxicity assay kit were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The LC3B antibody was obtained from Cell Signalling Technology. Matrigel Matrix was obtained from Corning.

Cell culture

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, grown in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, containing streptomycin/penicillin (100 µg/ml and 100 U/ml, respectively), in a humidified atmosphere with 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cells were differentiated as follows: the cells were seeded on Matrigel matrix-coated culture dishes and allowed to attach for 24 h. The cells were exposed to 10 μM retinoic acid every 2 days and the FBS content of the culture medium was then reduced to 2%. The cells were pre-treated for 7 days with ATX 1, 5, 10, 20 and 50 μM (ATX was added every 2 days at the same time that retinoic acid). After 7 days of differentiation, control cells and cells treated with ATX were used for the different determinations. We selected the doses of ATX according to the reported clinically relevant concentrations in plasma, which are in the micromolar range17,22. In vitro studies are good tools in the quest to find some of the cellular and molecular mechanism of the drugs used as a therapy in ADHD. Some of the advantages of using in vitro the human differentiated SH-SY5Y cells are: differentiated cells possess more morphological, ultrastructural, biochemical, and electrophysiological similitude to neurons. The cells present the formation of synaptophysin-positive functional synapses, and induction of neuron-specific enzymes, neurotransmitters, and neurotransmitter receptors. The differentiated cells could express the norepinephrine transporter and the vesicular monoamine transporter, characteristic of adrenergic neurons. Besides, the differentiated cells have many characteristics of dopaminergic neurons, since are positive for tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine-β-hydroxylase, as well as express the dopamine transporter58,59.

Cytotoxicity assay

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assay was performed in differentiated cells treated with different concentrations of ATX using an LDH cytotoxicity assay kit, according to the manufacturer´s instructions (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Briefly, cells were seeded and differentiated on white, clear-bottom 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 106 cells per well. Five microliters of media from each well was then mixed with 95 μL of the reaction mixture (supplied in the kit), followed by the measurement of fluorescence at excitation and emission wavelengths of 535 nm and 587 nm, respectively. Each experiment was repeated three times using separate cultures.

MTT assay

Cell viability was determined using MTT assay (Sigma, Saint Louis MO, USA) in differentiated cells treated with the highest concentrations of ATX or with ascorbic acid (50 μM). Cells were seeded and differentiated on plates at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere and 5% CO2. The medium was removed, cells were washed and 100 μl of MTT of stock (5 mg/ml) in PBS was added to the cultures, after 4 h of incubation, the solution was removed and 100 μl of isopropanol was added to dissolve the resulting formazan salts. Following 5 min, the wells were read at 540 nm on an spectrophotometer. Each experiment was repeated three times using the same experimental conditions. The results were expressed as percentage.

Measurement of mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

Once differentiated on coverslips for 7 days, cells were loaded with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (pH 7.4), containing 1 μM calcein-AM and 25 nM TMRM for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Images were acquired using a Zeiss Axiovert 100M confocal microscope with a Plan-Neofluar ×63/1.25 oil immersion objective lens at RT. Calcein-AM was excited at a wavelength of 488 nm and TMRM fluorescence at 543 nm using a laser. All the images were analysed using the software Fiji ImageJ. The measurements of mitochondrial mass and ΔΨm were realised as previously reported41.

Measurements of cytosolic and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS)

After differentiation, cells were loaded with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution and dihydroethidine (DHE) (5 μM - for the measurement of cytosolic ROS) or with MitoSOX (5 μM - for the measurement of mitochondrial ROS) for 15 min and remained in solution for the duration of the experiment. Images were acquired using a Zeiss Axiovert 100M confocal microscope with a Plan-Neofluar ×63/1.25 oil immersion objective lens at RT. DHE and MitoSOX fluorescence were excited at wavelength of 543 and 488 nm respectively. The increase in red fluorescence (excited at 543 or 488 nm and measured at >560 nm with a long-pass filter) gives the rate of cytosolic and mitochondrial ROS generation. In all experiments, data were collected every 15 s for 16 min. The rate of cytosolic and mitochondrial ROS in cells treated with ATX was compared with the rate of ROS in control cells.

Western blotting

Total proteins were extracted using standard protocols. Proteins were subjected to SDS–PAGE, polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) blocked for 2 h at RT with 5% non-fat dried milk in PBS, 0.2% Tween-20 (PBST). Blocked membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. The membranes were then rinsed three times in PBST and incubated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 h at RT. Chemoluminescence signal was produced with (ECL-BioRad) and detected by Fusion-Solo WL system (Vilber Lourmat). Protein bands were quantified densitometrically with Fiji ImageJ software.

LC3B-GFP autophagosome analysis

We used BacMam LC3B-GFP as a marker for autophagy. Once differentiated on coverslips for 7 days, control cells and cells treated with different concentrations of ATX were transfected with BacMam LC3B-GFP or BacMam LC3B (G120A)-GFP viral particles (MOI = 30) for 18–20 h, according to the Premo Autophagy Sensor Kit. LC3B-GFP and LC3B (G120A)-GFP signals were monitored and captured using a Zeiss Axiovert 100M confocal microscope.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism Software (Version 6.01, Inc., La Jolla, CA). The mean ± S.E.M. values from at least three independent experiments are shown. The data were compared using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni test. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fondos Federales HIM 2015/022 SSA 1160 and HIM 2017/005 SSA 1301 and ISN CAEN Award for Juan Carlos Corona.

Author Contributions

S.C.-T., D.G.-B., D.V.-G., R.G.-P., M.S.-G. and J.C.C., performed the experiments; J.C.C. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-49609-9.

References

- 1.Biederman J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366:237–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66915-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corona JC. Natural Compounds for the Management of Parkinson’s Disease and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:4067597. doi: 10.1155/2018/4067597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince J. Catecholamine dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an update. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:S39–45. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318174f92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joseph N, Zhang-James Y, Perl A, Faraone SV. Oxidative Stress and ADHD: A Meta-Analysis. J Atten Disord. 2015;19:915–924. doi: 10.1177/1087054713510354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopresti AL. Oxidative and nitrosative stress in ADHD: possible causes and the potential of antioxidant-targeted therapies. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2015;7:237–247. doi: 10.1007/s12402-015-0170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sezen H, et al. Increased oxidative stress in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Redox Rep. 2016;21:248–253. doi: 10.1080/13510002.2015.1116729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceylan M, Sener S, Bayraktar AC, Kavutcu M. Oxidative imbalance in child and adolescent patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:1491–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulut M, et al. Malondialdehyde levels in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:435–438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulut M, et al. Lipid peroxidation markers in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: new findings for oxidative stress. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209:638–642. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selek S, Savas HA, Gergerlioglu HS, Bulut M, Yilmaz HR. Oxidative imbalance in adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychol. 2008;79:256–259. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leffa DT, et al. Increased Oxidative Parameters and Decreased Cytokine Levels in an Animal Model of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Neurochem Res. 2017;42:3084–3092. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bymaster FP, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:699–711. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Upadhyaya HP, et al. A review of the abuse potential assessment of atomoxetine: a nonstimulant medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;226:189–200. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-2986-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koda K, et al. Effects of acute and chronic administration of atomoxetine and methylphenidate on extracellular levels of noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin in the prefrontal cortex and striatum of mice. J Neurochem. 2010;114:259–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanson CJ, et al. Effect of the attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder drug atomoxetine on extracellular concentrations of norepinephrine and dopamine in several brain regions of the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2006;50:755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fumagalli F, et al. Sub-chronic exposure to atomoxetine up-regulates BDNF expression and signalling in the brain of adolescent spontaneously hypertensive rats: comparison with methylphenidate. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludolph AG, et al. Atomoxetine acts as an NMDA receptor blocker in clinically relevant concentrations. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elia J, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation study associates metabotropic glutamate receptor gene networks with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet. 2012;44:78–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorval KM, et al. Association of the glutamate receptor subunit gene GRIN2B with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:444–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi T, Washiyama K, Ikeda K. Inhibition of G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels by the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors atomoxetine and reboxetine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1560–1569. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lempp T, et al. Altered gene expression in the prefrontal cortex of young rats induced by the ADHD drug atomoxetine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;40:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barygin OI, et al. Inhibition of the NMDA and AMPA receptor channels by antidepressants and antipsychotics. Brain Res. 2017;1660:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikolaev, M. et al. Modulation of proton-gated channels by antidepressants. ACS Chem Neurosci (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bindoli A, Rigobello MP, Deeble DJ. Biochemical and toxicological properties of the oxidation products of catecholamines. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;13:391–405. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90182-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Napolitano A, Manini P, d’Ischia M. Oxidation chemistry of catecholamines and neuronal degeneration: an update. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18:1832–1845. doi: 10.2174/092986711795496863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y. Catecholamine autotoxicity. Implications for pharmacology and therapeutics of Parkinson disease and related disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;144:268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neri M, et al. Correlation between cardiac oxidative stress and myocardial pathology due to acute and chronic norepinephrine administration in rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:156–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spencer WA, Jeyabalan J, Kichambre S, Gupta RC. Oxidatively generated DNA damage after Cu(II) catalysis of dopamine and related catecholamine neurotransmitters and neurotoxins: Role of reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saller S, et al. Norepinephrine, active norepinephrine transporter, and norepinephrine-metabolism are involved in the generation of reactive oxygen species in human ovarian granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1472–1483. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paris I, et al. Monoamine transporter inhibitors and norepinephrine reduce dopamine-dependent iron toxicity in cells derived from the substantia nigra. J Neurochem. 2005;92:1021–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deo SH, Jenkins NT, Padilla J, Parrish AR, Fadel PJ. Norepinephrine increases NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells via alpha-adrenergic receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R1124–1132. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00347.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Troadec JD, et al. Noradrenaline provides long-term protection to dopaminergic neurons by reducing oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 2001;79:200–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao W, Iwai C, Keng PC, Vulapalli R, Liang CS. Norepinephrine-induced oxidative stress causes PC-12 cell apoptosis by both endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial intrinsic pathway: inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase survival pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1373–1384. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang Y, Pei L, Li S, Wang M, Liu F. Extracellular dopamine induces the oxidative toxicity of SH-SY5Y cells. Synapse. 2008;62:797–803. doi: 10.1002/syn.20554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montecinos V, et al. Vitamin C is an essential antioxidant that enhances survival of oxidatively stressed human vascular endothelial cells in the presence of a vast molar excess of glutathione. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15506–15515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang YN, Yang LY, Wang JY, Lai CC, Chiu CT. L-Ascorbate Protects Against Methamphetamine-Induced Neurotoxicity of Cortical Cells via Inhibiting Oxidative Stress, Autophagy, and Apoptosis. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:125–136. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9561-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Case AJ, Roessner CT, Tian J, Zimmerman MC. Mitochondrial Superoxide Signaling Contributes to Norepinephrine-Mediated T-Lymphocyte Cytokine Profiles. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altunkaynak, B. Z. et al. In Melatonin, Neuroprotective Agents and Antidepressant Therapy (eds López-Muñoz, F. et al.) 825–845 (Springer, 2016).

- 39.Berridge CW, et al. Methylphenidate preferentially increases catecholamine neurotransmission within the prefrontal cortex at low doses that enhance cognitive function. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Comim CM, et al. Methylphenidate treatment causes oxidative stress and alters energetic metabolism in an animal model of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2014;26:96–103. doi: 10.1017/neu.2013.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corona JC, de Souza SC, Duchen MR. PPARgamma activation rescues mitochondrial function from inhibition of complex I and loss of PINK1. Exp Neurol. 2014;253:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corona JC, Duchen MR. PPARgamma as a therapeutic target to rescue mitochondrial function in neurological disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;100:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corona JC, Duchen MR. Impaired mitochondrial homeostasis and neurodegeneration: towards new therapeutic targets? J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2015;47:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s10863-014-9576-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galluzzi L, Pietrocola F, Levine B, Kroemer G. Metabolic control of autophagy. Cell. 2014;159:1263–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jesinkey SR, Korrapati MC, Rasbach KA, Beeson CC, Schnellmann RG. Atomoxetine prevents dexamethasone-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;351:663–673. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.217380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reid WM, Hamm RJ. Post-injury atomoxetine treatment improves cognition following experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:248–256. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hou QX, et al. Neuroprotective effects of atomoxetine against traumatic spinal cord injury in rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2016;19:272–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campanella M, et al. IF1, the endogenous regulator of the F(1)F(o)-ATPsynthase, defines mitochondrial volume fraction in HeLa cells by regulating autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y, Gibson SB. Is mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species a trigger for autophagy? Autophagy. 2008;4:246–248. doi: 10.4161/auto.5432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cubells JF, Rayport S, Rajendran G, Sulzer D. Methamphetamine neurotoxicity involves vacuolation of endocytic organelles and dopamine-dependent intracellular oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2260–2271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02260.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larsen KE, Fon EA, Hastings TG, Edwards RH, Sulzer D. Methamphetamine-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons involves autophagy and upregulation of dopamine synthesis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8951–8960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08951.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu CW, et al. Enhanced oxidative stress and aberrant mitochondrial biogenesis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells during methamphetamine induced apoptosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;220:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen Y, McMillan-Ward E, Kong J, Israels SJ, Gibson SB. Mitochondrial electron-transport-chain inhibitors of complexes I and II induce autophagic cell death mediated by reactive oxygen species. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4155–4166. doi: 10.1242/jcs.011163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witcher JW, et al. Atomoxetine pharmacokinetics in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13:53–63. doi: 10.1089/104454603321666199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sauer JM, Ring BJ, Witcher JW. Clinical pharmacokinetics of atomoxetine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:571–590. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kielbasa W, Kalvass JC, Stratford R. Microdialysis evaluation of atomoxetine brain penetration and central nervous system pharmacokinetics in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:137–142. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xie HR, Hu LS, Li GY. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line: in vitro cell model of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123:1086–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kovalevich J, Langford D. Considerations for the use of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells in neurobiology. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1078:9–21. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-640-5_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.