Abstract

Background

Identification of biomarkers associated with benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II/III colon cancer is an important task.

Methods

Vessel density (VD) and tumour stroma were analysed in a randomised-trial-derived discovery cohort (n = 312) and in a stage II/III group of a population-based validation cohort (n = 85). VD was scored separately in the tumour centre, invasive margin and peritumoral stroma compartments and quantitated as VD/total analysed tissue area or VD/stroma area.

Results

High stroma-normalised VD in the invasive margin was associated with significantly longer time to recurrence and overall survival (OS) (p = 0.002 and p = 0.006, respectively) in adjuvant-treated patients of the discovery cohort, but not in surgery-only patients. Stroma-normalised VD in the invasive margin and treatment effect were significantly associated according to a formal interaction test (p = 0.009). Similarly, in the validation cohort, high stroma-normalised VD was associated with OS in adjuvant-treated patients, although statistical significance was not reached (p = 0.051).

Conclusion

Through the use of novel digitally scored vessel-density-related metrics, this exploratory study identifies stroma-normalised VD in the invasive margin as a candidate marker for benefit of adjuvant 5-FU-based chemotherapy in stage II/III colon cancer. The findings, indicating particular importance of vessels in the invasive margin, also suggest biological mechanisms for further exploration.

Subject terms: Colon cancer, Predictive markers

Background

Improved imaging and surgical procedures, including total mesorectal excision in rectal cancer and mesocolic excision in colon cancer, have dramatically improved outcomes in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients.1–3 Despite these successes, recurrences in stage II colon cancer are still seen in up to one-quarter of the patients3–5 and in stage III in up to every other patient. Adjuvant therapy is therefore recommended, reducing the risks by about one-third.6,7

Patients with resected tumours with metastatic growth in regional lymph nodes (stage III) generally receive treatment after surgical removal.7 The benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with lymph-node-negative disease remains a subject of discussion,6,8 and adjuvant chemotherapy is not recommended for most patients with stage II colon cancer.7,9 It is generally believed, however that a fraction of stage II group benefits from the adjuvant treatment, and most guidelines recommend therapy for high-risk groups. Criteria for high risk of recurrence include a low number of sampled lymph nodes (<12), low tumour differentiation and T4 stage according to US criteria (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#colon) and vascular invasion, lymphatic or perineural invasion and obstruction (ESMO criteria).7 For stage III, a combination of oxaliplatin with a fluoropyrimidine is routinely recommended. However, the generalisation of the addition of oxaliplatin has been questioned in several studies, particularly in patients above 70 years.10

Taken together, this situation identifies a need for identification of better criteria for stratification of patients to groups who benefit sufficiently from adjuvant treatment in both stage II and stage III colon cancer,11,12 predicting the need for adjuvant treatment, i.e. the presence of subclinical deposits, and the benefit of such chemotherapy, i.e. reducing the number of deposits, leading to a recurrence and ultimate death, is a highly active research area.13 Candidate markers subject to ongoing validation include CD133 and MMR status.14–16

A potential impact of tumour vessel characteristics on drug delivery and sensitivity to chemotherapy is suggested by experimental studies.17–20 Recent studies also imply tumour vasculature as an important component of cellular niches harbouring chemo-resistant cancer stem cells.21–24 Properties of the vasculature also affect cancer cell intravasation and establishment of distant metastases.25–30 Notably, while earlier studies on prognostic or response-predictive significance of vessel density (VD) have mostly used semi-quantitative visual scoring procedures, recent studies have taken the advantage of automated digital-image analyses for more observer-independent determinations of vascular features.20,31–33

In this study, we use CD34 as a vessel marker and PDGFR-β as a marker for tumour stroma. This study has explored the potential predictive significance of VD in two well-annotated clinical cohorts. The study thereby goes beyond earlier studies firstly, through separate analyses of different anatomical regions, and secondly, by distinct analyses of total tumour VD and stroma-normalised VD.

Methods

Clinical data and study cohorts

Two independent collections of a surgically resected material of colon cancers were used. For the Discovery cohort, we used tissue material derived from 312 patients from a Nordic randomised clinical trial performed to evaluate the efficacy of 5-FU (5-fluorouracil)-based adjuvant chemotherapy.34 The study included 2224 patients younger than 76 years with radically resected stage II–III colorectal cancer operated during the time period 1991–1997. These patients were randomised to either surgery alone or surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. The chemotherapy regimens included 5-FU/leucovorin for 4–5 months, according to either a modified Mayo Clinic or the Nordic schedule or 5-FU/levamisole during 12 months. No patient received radiotherapy or chemotherapy prior to the surgery. Tissue from surgical resection was used. Fresh sections were cut for the study.

The ethical committee of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, approved the analysis (Dnr 00-260, 2014/664-32).

As a Validation cohort, we used colon cancer tissue microarray (TMA) derived from a population-based CRC collection obtained in the context of U-CAN, Sweden (http://www.u-can.uu.se/about-u-can/).35 U-CAN patients from the county of Uppsala (Sweden) diagnosed with stage II/III colon cancer between 2010 and 2014 who had radical surgery and survived at least 6 weeks after surgery were included in the validation cohort. Patients were treated within routine care with adjuvant therapy, according to ESMO guidelines. TMAs were made from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks of primary tumour. Each case is represented on the TMA with two cores derived from the central part of the tumour and two cores from the invasive margin. No rectal cancer cases were included in the study.

The regional ethical committees in Uppsala, Sweden approved the analysis (Dnr 2010/198 and Dnr 2015/419).

IHC procedures

Four-micrometer-thick sections were de-paraffinised, rehydrated and rinsed in distilled H2O. The antigen retrieval with boiling in pH 10.0 retrieval buffer was performed in decloaking chamber (Biocare Medical) at 110 °C for 5 min. Sections were then incubated with blocking solution for 30 min and with PDGFR-β rabbit monoclonal antibody (#3169, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), 2 µg/ml at dilution 1:100 overnight. The sections were incubated with the polymer system (ImmPRESS™-AP Polymer Anti-Rabbit IgG MP-5401) for 1 h at room temperature and developed with Vector® Blue AP Substrate Kit (SK-5300, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). To inactivate alkaline phosphatase reagents, the sections were heated in decloaking chamber at 95 °C for 5 min, in pH 9.0 solution. This was followed by an incubation with blocking solution for 30 min and with anti-CD34 (Clone JC70A; Dako, Inc., Denmark) at dilution 1:100 overnight. Sections were then incubated with polymer system (ImmPRESS™-AP Polymer Anti-Mouse IgG, MP-5402, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h at room temperature, and developed with Vector® Red AP Substrate Kit (SK-5100, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Quantitative analysis of immunohistochemical staining

The double-stained slides of the discovery cohort (regular sections) were scanned by a V-slide-scanning microscope (Metasystems, Alltlussheim, Germany), with × 10 objective and RGB-led illumination for colour deconvolution. The Metaviewer (Metasystems, Alltlussheim, Germany) was used to view the scanned digital slides. Each tumour sample was reviewed by the same pathologist (IH) and three regions/compartments were selected: tumour centre, invasive margin and peritumoral stroma.

The region selection was morphology-based and was made with the intention to capture as big area as possible. For the invasive margin, the tumour region facing the adjacent non-malignant tissue was selected. The rest of the tumour mass was considered as tumour centre. Peritumoral non-malignant tissue was only selected if characterised by fibrosis. Non-malignant fat tissue or muscle tissue was not included into selection. In all three compartments, the regions without necrosis and artefacts was selected. Small artefacts were removed manually.

All cases were reviewed by the second pathologist (AM). A joint decision was made in conflicting cases. The region selection is schematically illustrated in Supp Fig. 1a. These compartments were annotated and saved in .tif format as individual images.

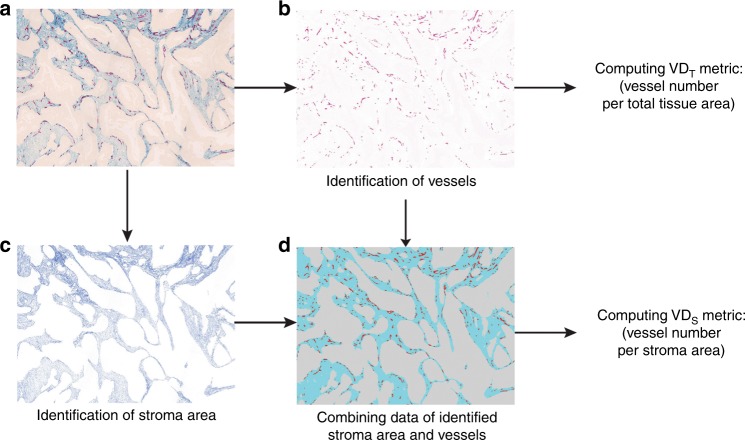

Fig. 1.

Determination of the ‘VDT’ and ‘VDs’ metrics. The original image was double stained for vessels with an antibody against CD34 (red) and for stroma with a PDGFR-β antibody (blue) (a) and was used to quantify vessels (b). The PDGFR-β-positive sub-regions, defining the stromal area, are illustrated in (c). To obtain ‘VDT’ values, the number of vessels per total tissue area was determined (b). To obtain ‘VDS’ values, the number of vessels per stroma area was determined (d)

The double-stained TMA slides of the validation cohort were scanned by Aperio Scanscope AT with × 20 objective. Pictures corresponding to the individual TMA cores were extracted and saved in .tif format as individual images. Most of the cases in this cohort were represented by two cores from tumour centre and two cores from the invasive margin. The cores of the same origin were treated for image analysis as one entire tissue sample.

The images were then used for automated image analyses to define the total tissue area, stromal area and vessel quantity (for details of this methodology see refs. 33,36). Vessels were identified by CD34 staining and quantified by an in-house developed image analysis algorithm (ImageJ software). The total tissue area was identified on the pre-selected images, representing the three tumour compartments described above. Blank areas present on the selected regions were excluded from the total tissue area quantification. PDGFR-β-positive regions were considered as stromal (for details see Materials and Methods in ref. 36). Vessel quantity and total tissue area were used to compute the ‘VDT’ metric (number of vessels per total analysed tissue area). Vessel quantity and PDGFR-β-positive stroma regions were used to compute the ‘VDS’ metric (number of vessels per stroma area).

For each of these three compartments, two values were calculated: number of vessels per analysed total tissue area (VDT) and number of vessels per tumour stroma area (VDS), making together six VD metrics per case: VDTCT, VDTIM, VDTPeri, VDSCT, VDSIM and VDSPeri. Because in the validation cohort only tissue material from tumour centre and invasive margin was available (but not for peritumoral tissue), four metrics from two compartments were produced in the validation cohort: VDTCT, VDTIM, VDSCT and VDSIM. The analytical pipeline is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1.

Tumour budding and configuration of the invasive border

Assessment of the configuration of the tumour border was done according to recommendations of Morikawa et al.37 The growth pattern was categorised into pushing (expansile), intermediate or infiltrative. A pushing growth pattern was considered a circumscribed tumour border. An infiltrative pattern was characterised by the presence of irregular clusters, small islands of cancer cells or small glands without a distinct border in the area of the invasive front. Appearance of the large and medium-sized glands at the invasive border was linked to the intermediate growth pattern. The assessment was performed independently by a pathologist (AM) and a clinical researcher (MK) after extensive training. In all cases of discrepancy in the scoring between the two observers, a collegial decision was made.

Tumour budding evaluation was performed, using as a model the guidelines of Karamitopolou et al.38 The trained pathologist (AM) identified ten fields of view on the digitalised slides, along the area of maximal invasion of the tumour. The area of the fields corresponded to the high-power field area of the microscopes used for the diagnostic routines. The number of tumour buds was counted by two independent observers (AM and MK) in each area and the average value was calculated. It was then used to dichotomise cases into high-budding (having ≥ 10 buds) and low-budding (<10 buds) groups. All cases with inter-observer difference in the final budding score were reviewed and a collegial decision was made.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS V20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and R software, version 3.3.3 (R Core Team (2017)). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL (https://www.R-project.org/), and integrated development environment RStudio, version 1.0.143 (RStudio Team (2015). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, URL http://www.rstudio.com/) with the following packages: gdata, ggplot, corrplot, PerformanceAnalytics, scales, rms, survival, made4, reshape, plyr and maxstat.

Time to recurrence (TTR) was computed as the time from surgery to the first documented disease progression, including local recurrence or distant metastases or death due to colon cancer, whichever occurred first.39 Overall survival (OS) was the time from surgery to death due to any reason. To estimate relative hazards in both univariate and multivariable models, a Cox proportional hazards model was used. For the analyses of associations between VD and clinical characteristics, chi-square test was used.

All statistical tests were two-sided and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The correction for the multiple testing was applied in the exploratory part of the study, using the ‘BH' (aka ‘fdr') method of Benjamini, Hochberg and Yekutieli, and reported as ‘q-values’.

Results

Quantitative characterisation of six vessel-density-related features in a randomised-trial-derived colon cancer collection

The colon cancers from the Nordic adjuvant randomised clinical trial,34 investigating benefits of 5-FU-based chemotherapy in stage II/III CRC, have been used in previous studies for the identification of prognostic and predictive markers.

In this study, this collection was used as a discovery cohort to explore potential relationships between VD-related features and benefit of chemotherapy. For each of these compartments, two values were calculated: number of vessels per analysed total tissue area, including both tumour and stroma compartments (VDT) and number of vessels per tumour stroma area only, referred further in the text as ‘stroma-normalised VD’ or abbreviated as ‘VDS’. By this approach, we generated together at maximum six VD metrics per case (see Methods and Fig. 1).

Successful staining was obtained on 312 of originally 514 tumours. The Digital image analyses-derived data were collected as follows: 282 cases from the tumour centre, 285 cases from the invasive margin and 176 cases from the peritumoral stroma (see Supplementary Fig. 1B). The high rate of the case loss is explained by tissue damage and detachment during the antigen retrieval procedure. The number of the cases with analysed peritumoral stroma was also limited by the presence of fibroblastic tissue available for analysis (see Methods for more detail). To control potential selection bias, all three subpopulations were compared with regard to clinico-pathological characteristics, with no statistically significant difference observed (Supplementary Table 1), and treatment subgroups were compared in each of three subpopulations (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, we performed a comparative analysis of the survival of three subpopulations, sub-divided by treatment. No statistically significant differences were found in TTR or OS between the surgery-alone group and the group having surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results are similar to the overall results in the original study population, revealing a statistically non-significant absolute gain of 8% in OS in colon cancer stage III only.34

Initial analyses demonstrated significant differences between the three tumour compartments, regarding both VDT and VDS (Supplementary Fig. 3). VDT was the highest in peritumoral stroma regions, whereas VDS was higher in the tumour regions than in the surrounding peritumoral stroma. Additional analyses demonstrated moderate within-case pairwise associations of VDT and VDS, indicating the possibility that these metrics could capture different aspects of vessel biology (Supplementary Fig. 4). Interestingly, higher VDS in tumour centre and in the invasive margin was inversely associated with adverse factors, such as infiltrative configuration of the invasive border and high-budding score (Table 1).

Table 1.

Associations between VD in three tumour compartments and clinico-pathological characteristics in the discovery cohort

| Tumour centre | Invasive margin | Peritumoral stroma | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDSCT number (percent) | VDSIM number (percent) | VDSPeri number (percent) | |||||||

| Characteristic | Low | High | p | Low | High | p | Low | High | p |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <66 | 66 (23.4) | 56 (19.9) | 0.279 | 68 (23.9) | 62 (21.8) | 0.476 | 41 (23.3) | 42 (23.9) | 1.000 |

| ≥66 | 75 (26.6) | 85 (30.1) | 74 (26.0) | 81 (28.4) | 47 (26.7) | 46 (26.1) | |||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 69 (24.4) | 78 (27.7) | 0.340 | 69 (24.2) | 74 (26.0) | 0.636 | 44 (25.0) | 43 (24.4) | 1.000 |

| Female | 72 (25.5) | 63 (22.3) | 73 (25.6) | 69 (24.2) | 44 (25.0) | 45 (25.6) | |||

| Tumour site | |||||||||

| Proximala | 74 (26.2) | 75 (26.6) | 1.000 | 80 (28.1) | 83 (29.1) | 0.811 | 47 (26.7) | 50 (28.4) | 0.762 |

| Distal | 67 (23.8) | 66 (23.4) | 62 (21.8) | 60 (21.1) | 41 (23.3) | 38 (21.6) | |||

| Mismatch-repair status | |||||||||

| MMR proficient | 108 (41.1) | 118 (44.9) | 0.216 | 110 (41.4) | 106 (39.8) | 0.638 | 62 (38.3) | 65 (10.5) | 0.850 |

| MMR deficient | 22 (8.4) | 15 (5.7) | 23 (8.6) | 27 (10.2) | 18 (11.1) | 17 (10.5) | |||

| TS expression | |||||||||

| High | 103 (36.5) | 110 (39.0) | 0.406 | 106 (37.2) | 111 (38.9) | 0.581 | 70 (39.8) | 67 (38.1) | 0.717 |

| Low | 38 (13.5) | 31 (11.0) | 36 (12.6) | 32 (11.2) | 18 (10.2) | 21 (11.9) | |||

| Stage | |||||||||

| II | 57 (20.2) | 60 (21.3) | 0.809 | 51 (17.9) | 66 (23.2) | 0.092 | 32 (18.2) | 41 (23.3) | 0.221 |

| III | 84 (29.8) | 81 (28.7) | 91 (31.9) | 77 (27.0) | 56 (31.8) | 47 (26.7) | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||||||

| Yes | 71 (25.2) | 72 (25.5) | 1.000 | 77 (27.0) | 73 (25.6) | 0.636 | 47 (26.7) | 44 (25.0) | 0.763 |

| No | 70 (24.8) | 69 (24.5) | 65 (22.8) | 70 (24.6) | 41 (23.3) | 44 (25.0) | |||

| Invasive border configuration | |||||||||

| Pushing | 32 (12.2) | 64 (25.2) | <0.001 | 30 (11.7) | 69 (26.8) | <0.001 | 29 (18.1) | 43 (26.9) | 0.098 |

| Intermediate | 29 (11.4) | 29 (11.4) | 24 (9.3) | 34 (13.2) | 22 (13.8) | 19 (11.9) | |||

| Infiltrative | 61 (24.0) | 40 (15.7) | 71 (27.6) | 29 (11.3) | 28 (17.5) | 19 (11.9) | |||

| Budding | |||||||||

| Low | 79 (31.6) | 106 (42.4) | 0.021 | 76 (30.0) | 107 (42.3) | <0.001 | 58 (37.2) | 59 (37.8) | 1.0 |

| High | 39 (15.6) | 26 (10.4) | 47 (18.6) | 23 (9.1) | 20 (12.8) | 19 (12.2) | |||

| Grade of differentiation | |||||||||

| Well (G1) | 10 (3.7) | 17 (6.3) | 0.279 | 10 (3.7) | 15 (5.5) | 0.415 | 10 (6.0) | 9 (5.4) | 0.599 |

| Moderate (G2) | 97 (36.1) | 95 (35.3) | 95 (34.9) | 91 (33.5) | 54 (32.3) | 55 (32.9) | |||

| Poor (G3) | 28 (10.4) | 22 (8.2) | 34 (12.5) | 27 (9.9) | 23 (13.8) | 16 (9.6) | |||

| Relapse | |||||||||

| No | 148 (67.3) | 45 (72.6) | 0.536 | 93 (63.3) | 98 (71.0) | 0.169 | 37 (61.7) | 85 (73.3) | 0.124 |

| Yes | 72 (32.7) | 17 (27.4) | 54 (36.7) | 40 (29.0) | 23 (38.3) | 31 (26.7) | |||

VDS stroma-normalised vessel density (vessels per mm2), p p-value, TS thymidylate synthase. Pearson chi-square test was used for statistical analysis

a—to splenic flexure

Identification of high stroma-normalised vessel density as a candidate treatment effect-predictive marker for 5-FU-based adjuvant therapy

To identify a VD-related marker associated with the benefit of adjuvant therapy, all six metrics were analysed with regard to the ability to define subgroups, showing distinct patterns of response to adjuvant treatment. All analyses were performed using unbiased median-based cut-offs to define ‘marker-high' and ‘marker-low' subgroups. Separate analyses were performed using TTR or OS as the endpoint.

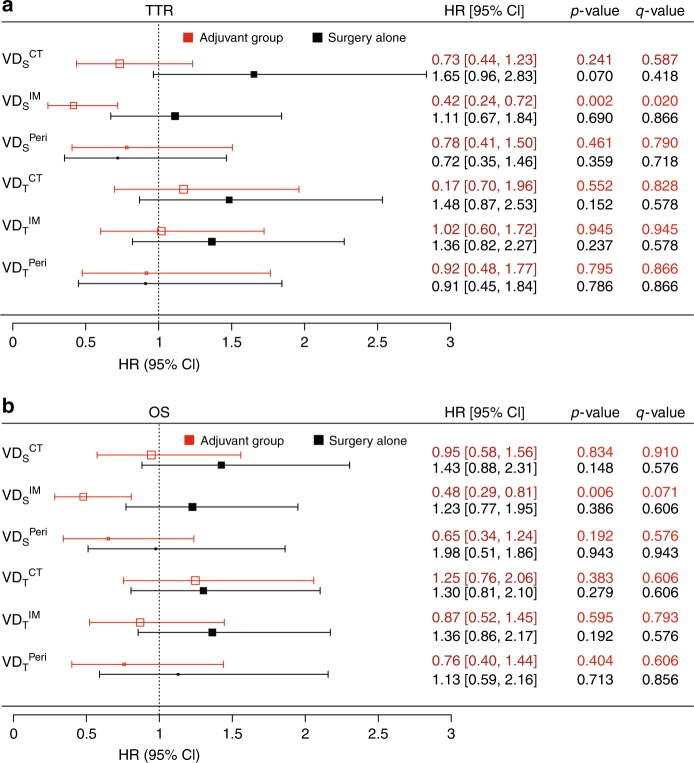

As shown in Fig. 2a, (red colour code), a clearly significant benefit of adjuvant therapy was observed in the (VDSIM)-high subgroup, using TTR as the endpoint. A similar pattern was observed when using OS as the endpoint (Fig. 2b, red colour code); however, the effect was less prominent, and the statistical significance lost, when correction for multiple testing was applied (Fig. 2, q-values). Nevertheless, the formal interaction test confirmed statistically significant interaction between treatment and the VDSIM (p = 0.009) in the OS-based analyses. Significant benefit of adjuvant treatment was not observed in any of the other subgroups, neither in the TTR- nor OS-based analyses.

Fig. 2.

Associations between VD and survival rates in stage II/III colon cancer in the discovery cohort. Plot illustrating the hazard ratios (squares on the graph and values on the right) and 95% CI (whiskers and values in the square parentheses), derived from Cox-regression analyses, for TTR (a) and OS (b) in the adjuvant chemotherapy group (red) and surgery-alone group (black). P-values, adjusted for multiple testing, are shown as q-values

To analyse, if the associations of VDSIM with TTR and OS in the adjuvant-treated group represent only effects of the markers on response to treatment, or also include associations between the marker and intrinsic aggressiveness of the disease, all VD metrics were analysed with regard to associations with outcomes in patients not receiving adjuvant therapy. No significant associations between the marker and TTR or OS were observed in these analyses (Fig. 2, black colour code).

MMR status has been reported to determine response to adjuvant therapy.16 Also in previous studies using material from the Nordic randomised clinical trial, MMR status and TS expression were linked to response to adjuvant therapy.40,41 Thus, to investigate the independence of the VDSIM metric, the multivariable analyses, including MMR status and TS expression together with age, gender and clinical stage, were performed separately in the surgery-alone and adjuvant-treated groups. As shown in Table 2, tumour stage was the only factor associated with TTR in the surgery-alone group. However, in adjuvant-treated patients, only VDSIM was independently associated with TTR (p = 0.017). Because VDSIM was strongly correlated with the shape of the tumour-invasive border and budding (Table 1), multivariable analyses were also performed with these three metrics. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, configuration of the tumour border was associated with TTR in the surgery-alone group, while in the adjuvant-treated group, VDSIM remained independently associated with TTR (p = 0.049).

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses including VDSIM, MMR, TS, gender, age and stage for TTR in colon cancer patients treated with surgery alone (A) or with adjuvant chemotherapy (B)

| Covariates | HR | 95.0% CI for HR | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| A) Surgery-alone group | ||||

| VDSIM (high vs low) | 0.968 | 0.567 | 1.655 | 0.906 |

| MMR status (proficient vs deficient) | 1.762 | 0.747 | 4.157 | 0.196 |

| TS expression (high vs low) | 1.881 | 0.965 | 3.666 | 0.064 |

| Gender (women vs men) | 1.137 | 0.657 | 1.968 | 0.647 |

| Age (66 years or older) | 1.345 | 0.777 | 2.329 | 0.289 |

| Stage (III vs II) | 3.500 | 1.830 | 6.692 | <0.001 |

| B) Adjuvant chemotherapy group | ||||

| VDSIM (high vs low) | 0.473 | 0.256 | 0.873 | 0.017 |

| MMR status (proficient vs deficient) | 1.307 | 0.579 | 2.949 | 0.520 |

| TS expression (high vs low) | 1.279 | 0.635 | 2.578 | 0.491 |

| Gender (women vs men) | 0.785 | 0.430 | 1.434 | 0.430 |

| Age (66 years or older) | 0.750 | 0.427 | 1.319 | 0.318 |

| Stage (III vs II) | 1.583 | 0.845 | 2.965 | 0.152 |

MMR DNA mismatch-repair status, TS thymidylate synthase, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval. Cox-regression model was used for statistical analysis

These analyses thus identified high VDS as a candidate biomarker for a stage II/III colon cancer subset benefiting from 5-FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy, with strongest data for VDSIM.

Preliminary validation of biomarker potential of VDSIM

To preliminary validate these findings, similar analyses were performed on an independent population-based CRC collection of stage II/III colon cancers, which included cases that had received adjuvant 5-FU alone or with oxaliplatin as part of risk-stratified routine clinical care.

The design of the tissue microarray of this CRC collection (see Methods for details) allowed collection of VDSCT, VDSIM, VDTCT and VDTIM data (82, 85, 82 and 85 cases, respectively). Following staining and metric collection, the dichotomisations were performed using median-based cut-off. Clinico-pathological characteristics of the validation cohort and the VDS metrics-low and -high groups are shown in Table 3, with no statistically significant difference observed, except a higher fraction of patients with age ≥ 66 years in the VDSIM group. We also compared the validation cohort and the respective group of the discovery cohort (adjuvant-treated, stage II/III, having material from the invasive margin). As expected, because of the population-based nature of the validation cohort, it has a higher fraction of stage III tumours. Also, a higher fraction of patients with distal tumour location was observed (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 3.

Associations between VDS and clinico-pathological characteristics in the validation cohort

| Tumour centre | Invasive margin | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDSCT number (percent) | VDSIM number (percent) | |||||

| Low | High | p | Low | High | p | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <66 | 21 (52.5) | 19 (47.5) | 0.659 | 25 (61.0) | 16 (39.0) | 0.040 |

| ≥66 | 20 (47.6) | 22 (52.4) | 17 (38.6) | 27 (61.4) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 22 (51.2) | 21 (48.8) | 0.825 | 18 (40.9) | 26 (59.1) | 0.104 |

| Female | 19 (48.7) | 20 (51.3) | 24 (58.5) | 17 (41.5) | ||

| Tumour site | ||||||

| Proximala | 17 (51.5) | 16 (48.5) | 0.822 | 17 (48.6) | 18 (51.4) | 0.897 |

| Distal | 24 (49.0) | 25 (51.0) | 25 (50.0) | 25 (50.0) | ||

| Stage | ||||||

| II | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.500 | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.476 |

| III | 35 (48.6) | 37 (51.4) | 36 (48.0) | 39 (52.0) | ||

| Relapse | ||||||

| Yes | 13 (59.1) | 9 (40.9) | 0.205 | 13 (56.5) | 10 (43.5) | 0.286 |

| No | 21 (42.9) | 28 (57.1) | 22 (43.1) | 29 (56.9) | ||

VDS stroma-normalised vessel density (vessels per mm2), p p-value, Pearson chi-square test used for statistical analysis

a—to splenic flexure

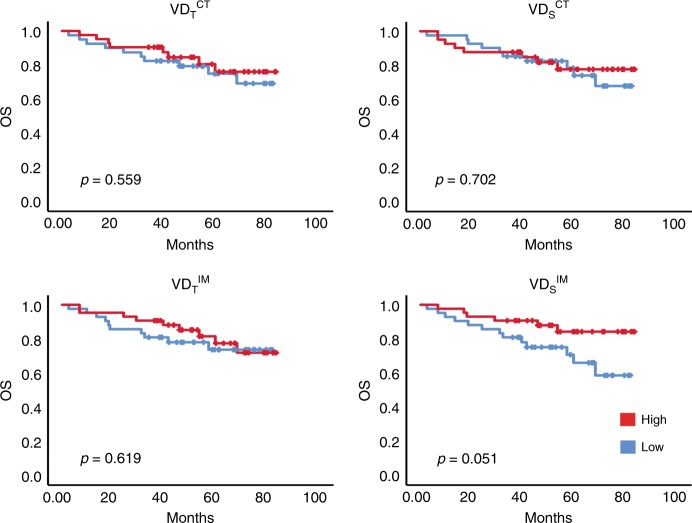

The VD metrics were analysed for association with OS. Similar to the discovery cohort, no survival associations were detected for the VDTCT, VDTIM and VDSCT. Instead, the VDSIM separated patients into groups with different survival rates, similar to the observation in the discovery cohort, although the statistical significance of this observation was marginal (p = 0.051, log-rank test) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Associations between VD and survival rates in stage II/III colon cancer with adjuvant treatment in the validation cohort. Kaplan–Meier plots for VDS -high (red) and -low (black) subgroups of adjuvant-treated patients in the validation cohort with OS as endpoints. Log-rank analyses were used for determination of p-values

Together, these analyses, although not yielding statistically significant results, support the finding from the analyses of the randomised-trial-derived discovery cohort, including indications that the stroma-normalised vessel-density metric performs better as a biomarker than the total vessel-density score.

Discussion

This study identifies high stroma-normalised VD in the invasive margin as a candidate marker for identification of patients benefiting of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II–III colon cancer.

In spite of a history of almost 30 years, the studies on vessel density as biomarkers have not been translated to any marker of clinical utility.42 It can be noted that most of these studies have focused on prognostic relevance. Already more than 10 years ago, meta-analyses of breast and colorectal cancer studies identified vessel density as a prognostic factor.43,44 However, many issues, including the remaining inconsistencies in findings and lack of assay standardisation have hampered the field. Recent studies have introduced other vessel-related metrics than vessel density to explore associations with benefit of chemotherapy. This includes e.g. studies linking pericyte status to response to chemotherapy (reviewed in refs. 45–47). In this context, this study has some special features; the study is emphasising a candidate marker of predictive, not prognostic relevance, the discovery cohort is composed of a population derived from a randomised controlled trial and the vessel metric is integrating normalisation to stroma and a spatial restriction to the invasive margin. Obviously, independent validation of the key finding in tumour collections from other randomised trials of adjuvant therapy in colorectal trials is a key topic for future studies. Future studies should also explore the relevance of the novel metric in other tumour types, including breast cancer, where earlier studies with other vessel-density metrics have failed to detect associations between vessel density and benefit of chemotherapy.48

Identification of robust and strong markers predicting benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy is recognised as a key challenge in translational colorectal cancer research.11,49,50 The most mature marker is deficiency in a mismatch repair, which is associated with lack of benefit in high-risk stage II CRC.16 A mesenchymal gene expression profile (CMS4) has also been linked to reduced benefit.51 Candidate markers associated with benefit of adjuvant therapy include thymidylate synthase (TS) and high Oncotype-DX risk score.41,52 As shown in Table 2, VDSIM remained significantly associated with TTR in multivariable analyses, also including TS and mismatch-repair status. This suggests that the predictive capacity of VDSIM is related to other biological mechanisms than those underlying the potential response-predictive capacity of TS and mismatch-repair status. This should be further analysed in analyses of other well-annotated cohorts.

The tumour collection of the discovery cohort is derived from a randomised trial, which makes it suitable for the identification of treatment-predictive biomarkers. For the validation cohort, a recent (2010–2014) population-based tumour collection in which patients were treated according to current ESMO guidelines was selected. Some limitations of the study are recognised. Concerning treatment regimens, it is noted, firstly, that the treatments used in the discovery cohort differ from present standards, and secondly, that the treatments used in the validation and discovery cohorts differ. Furthermore, limitations regarding the procedures for lymph-node dissection of the discovery cohort prevented stringent stage-specific analyses. Additional studies in other well-defined cohorts are therefore highly motivated.

Concerning analytical procedures, the study relies on digital scoring which should increase stringency and possibly also allow more quantitative scoring. Notably, continued development of the candidate biomarker towards clinical utility will require extensive standardisation efforts and additional work on selection of optimal cut-offs. From an analytical perspective, it should be noted that the preliminary data from the validation cohort were derived from the analyses of two representative TMA cores, each 1 mm in diameter, from the tumour centre and invasive margin, whereas the discovery cohort used large blocks for analyses. Future optimisation studies should address the issue of ‘inside-case' heterogeneity and how this can best be addressed.

The analyses of the surgery-alone group showed that in this population, VDSIM was not significantly associated with TTR or OS (Fig. 2). This suggests that VDSIM is related to the benefit of adjuvant therapy, without being coupled to the natural course or intrinsic aggressiveness of the disease. This notion is also supported by the fact that VDSIM is not significantly associated with stage in the discovery cohort (Table 1), or in the validation cohort (Table 3). Notably, VDSIM shows in the discovery cohort an inverse association with poor prognostic factors, such as budding and infiltrative growth (Table 2).

The underlying biology should be explored in future mechanistic studies. One possibility to consider in such efforts is that the vascular phenotype of the primary tumour is a proxy for a chemo-resistant population, in agreement with earlier experimental studies which have identified perivascular niches that host and support special cancer cell populations.21,23,24 Future studies should also investigate if the high stroma-normalised VD in the invasive margin is associated with certain driver mutations, or gene expression profiles, linked to the recently defined molecular subtypes of colon cancer.

From a general vascular biomarker perspective, the study confirms that increasing biological content in VD measurements, as done here by considering different compartments and normalisation to stroma abundance, can increase performance of VD-related markers. This finding should inspire to continued efforts, in many tumour types, of in-depth vascular profiling towards the ultimate goal of developing a predictive vascular biomarker of clinical utility.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Marja Hallström for outstanding technical support.

Author contributions

A.M. designed the study, performed sample staining, visual and digital quantification, analysed data, performed statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. I.H. performed assessment for the digitalized slides, region selection, quality control, contributed to the writing, and preparation of the manuscript. M.H. analysed data, performed statistical analysis, contributed to the writing, and preparation of the manuscript. M.K. performed assessment for the digitalized slides, contributed to the writing, and preparation of the manuscript. E.O. performed data collection for the validation cohort, contributed to the writing and preparation of the manuscript. P.R. performed sample and data collection for the discovery cohort, contributed to the writing and preparation of the manuscript. D.E. performed sample and data collection for the discovery cohort, contributed to the writing and preparation of the manuscript. A.P. contributed to the writing and preparation of the manuscript. F.P. performed sample and data collection for the validation cohort, TMA construction, contributed to the writing and preparation of the manuscript. T.S. contributed to the writing and preparation of the manuscript. B.G. contributed to the writing and preparation of the manuscript. A.Ö. designed the study, wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical committee of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, and the regional ethical committees in Uppsala, Sweden approved the analysis (Dnr 00-260, 2014/664-32) and (Dnr 2010/198 and Dnr 2015/419), respectively.

Funding

Studies were supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, Radiumhemmets forskningsfonder and the STARGET Linné-grant from the Swedish Research Council. A.M. was also supported by a grant from Svenska Institutet. Marja Hallström was supported by Bengt Ihres foundation.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Data availability

The data sets used and analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ina Hrynchyk, Mercedes Herrera

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41416-019-0519-1.

References

- 1.Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Ryall RD, Sexton R, MacFarlane JK. Rectal cancer: the Basingstoke experience of total mesorectal excision, 1978-1997. Arch. Surg. 1998;133:894–899. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.8.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sondenaa K, Quirke P, Hohenberger W, Sugihara K, Kobayashi H, Kessler H, et al. The rationale behind complete mesocolic excision (CME) and a central vascular ligation for colon cancer in open and laparoscopic surgery: proceedings of a consensus conference. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2014;29:419–428. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1818-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertelsen CA, Neuenschwander AU, Jansen JE, Wilhelmsen M, Kirkegaard-Klitbo A, Tenma JR, et al. Disease-free survival after complete mesocolic excision compared with conventional colon cancer surgery: a retrospective, population-based study. Lancet. Oncol. 2015;16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernhoff R, Martling A, Sjovall A, Granath F, Hohenberger W, Holm T. Improved survival after an educational project on colon cancer management in the county of Stockholm-a population based cohort study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015;41:1479–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deijen CL, Vasmel JE, de Lange-de Klerk ESM, Cuesta MA, PLO Coene, Lange JF, et al. Ten-year outcomes of a randomised trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for colon cancer. Surg. Endosc. 2017;31:2607–2615. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5270-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bockelman C, Engelmann BE, Kaprio T, Hansen TF, Glimelius B. Risk of recurrence in patients with colon cancer stage II and III: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature. Acta. Oncol. 2015;54:5–16. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.975839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, Valentini V, Glimelius B, Haustermans K, et al. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. a personalized approach to clinical decision making. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23:2479–2516. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang SH, Efron JE, Berho ME, Wexner SD. Dilemma of stage II colon cancer and decision making for adjuvant chemotherapy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;219:1056–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson AB, 3rd, Schrag D, Somerfield MR, Cohen AM, Figueredo AT, Flynn PJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:3408–3419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tournigand C, Andre T, Bonnetain F, Chibaudel B, Lledo G, Hickish T, et al. Adjuvant therapy with fluorouracil and oxaliplatin in stage II and elderly patients (between ages 70 and 75 years) with colon cancer: subgroup analyses of the Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:3353–3360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.5645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Påhlman Lars A., Hohenberger Werner M., Matzel Klaus, Sugihara Kenichi, Quirke Philip, Glimelius Bengt. Should the Benefit of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Colon Cancer Be Re-Evaluated? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(12):1297–1299. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osterman E, Glimelius B. Recurrence risk after up-to-date colon cancer staging, surgery, and pathology: analysis of the entire Swedish population. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2018;61:1016–1025. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dienstmann R, Salazar R, Tabernero J. Personalizing colon cancer adjuvant therapy: selecting optimal treatments for individual patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:1787–1796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong CW, Kim LG, Kong HH, Low LY, Iacopetta B, Soong R, et al. CD133 expression predicts for non-response to chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2010;23:450–457. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertagnolli MM, Niedzwiecki D, Compton CC, Hahn HP, Hall M, Damas B, et al. Microsatellite instability predicts improved response to adjuvant therapy with irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in stage III colon cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Protocol 89803. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:1814–1821. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, Thibodeau SN, Labianca R, Hamilton SR, et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:3219–3226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tavora B, Reynolds LE, Batista S, Demircioglu F, Fernandez I, Lechertier T, et al. Endothelial-cell FAK targeting sensitizes tumours to DNA-damaging therapy. Nature. 2014;514:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bridgeman VL, Vermeulen PB, Foo S, Bilecz A, Daley F, Kostaras E, et al. Vessel co-option is common in human lung metastases and mediates resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy in preclinical lung metastasis models. J. Pathol. 2017;241:362–374. doi: 10.1002/path.4845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuczynski Elizabeth A., Yin Melissa, Bar-Zion Avinoam, Lee Christina R., Butz Henriett, Man Shan, Daley Frances, Vermeulen Peter B., Yousef George M., Foster F. Stuart, Reynolds Andrew R., Kerbel Robert S. Co-option of Liver Vessels and Not Sprouting Angiogenesis Drives Acquired Sorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2016;108(8):djw030. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tolaney SM, Boucher Y, Duda DG, Martin JD, Seano G, Ancukiewicz M, et al. Role of vascular density and normalization in response to neoadjuvant bevacizumab and chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2015;112:14325–14330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518808112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, Hogg TL, Fuller C, Hamner B, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitt LA, Tikhonova AN, Hu H, Trimarchi T, King B, Gong Y, et al. CXCL12-producing vascular endothelial niches control acute T Cell leukemia maintenance. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao Z, Ding BS, Guo P, Lee SB, Butler JM, Casey SC, et al. Angiocrine factors deployed by tumor vascular niche induce B cell lymphoma invasiveness and chemoresistance. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:350–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayakawa Y, Ariyama H, Stancikova J, Sakitani K, Asfaha S, Renz BW, et al. Mist1 expressing gastric stem cells maintain the normal and neoplastic gastric epithelium and are supported by a perivascular stem cell niche. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:800–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bockhorn M, Jain RK, Munn LL. Active versus passive mechanisms in metastasis: do cancer cells crawl into vessels, or are they pushed? Lancet. Oncol. 2007;8:444–448. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70140-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Branco-Price C, Zhang N, Schnelle M, Evans C, Katschinski DM, Liao D, et al. Endothelial cell HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha differentially regulate metastatic success. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderberg C, Cunha SI, Zhai Z, Cortez E, Pardali E, Johnson JR, et al. Deficiency for endoglin in tumor vasculature weakens the endothelial barrier to metastatic dissemination. J Exp Med. 2013;210:563–579. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wieland E, Rodriguez-Vita J, Liebler SS, Mogler C, Moll I, Herberich SE, et al. Endothelial Notch1 activity facilitates metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf MJ, Hoos A, Bauer J, Boettcher S, Knust M, Weber A, et al. Endothelial CCR2 signaling induced by colon carcinoma cells enables extravasation via the JAK2-Stat5 and p38MAPK pathway. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Padhan N, Sjostrom EO, Roche FP, Testini C, Honkura N, et al. VEGFR2 pY949 signalling regulates adherens junction integrity and metastatic spread. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corvigno S., Wisman G. B., Mezheyeuski A., van der Zee A. G., Nijman H. W., Avall-Lundqvist E. et al. Markers of fibroblast-rich tumor stroma and perivascular cells in serous ovarian cancer: inter- and intra-patient heterogeneity and impact on survival. Oncotarget 2016; 10.18632/oncotarget.7613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Frodin M, Mezheyeuski A, Corvigno S, Harmenberg U, Sandstrom P, Egevad L, et al. Perivascular PDGFR-beta is an independent marker for prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2017;116:195–201. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka N, Kanatani S, Tomer R, Sahlgren C, Kronqvist P, Kaczynska D, et al. Whole-tissue biopsy phenotyping of three-dimensional tumours reveals patterns of cancer heterogeneity. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017;1:796–806. doi: 10.1038/s41551-017-0139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glimelius B, Dahl O, Cedermark B, Jakobsen A, Bentzen SM, Starkhammar H, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer: a joint analysis of randomised trials by the Nordic Gastrointestinal Tumour Adjuvant Therapy Group. Acta. oncologica. 2005;44:904–912. doi: 10.1080/02841860500355900a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glimelius B, Melin B, Enblad G, Alafuzoff I, Beskow A, Ahlstrom H, et al. U-CAN: a prospective longitudinal collection of biomaterials and clinical information from adult cancer patients in Sweden. Acta. Oncol. 2018;57:187–194. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1337926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corvigno S, Wisman GB, Mezheyeuski A, van der Zee AG, Nijman HW, Avall-Lundqvist E, et al. Markers of fibroblast-rich tumor stroma and perivascular cells in serous ovarian cancer: Inter- and intra-patient heterogeneity and impact on survival. Oncotarget. 2016;7:18573–18584. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Qian ZR, Mino-Kenudson M, Hornick JL, Yamauchi M, et al. Prognostic significance and molecular associations of tumor growth pattern in colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012;19:1944–1953. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2174-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karamitopoulou E, Zlobec I, Kolzer V, Kondi-Pafiti A, Patsouris ES, Gennatas K, et al. Proposal for a 10-high-power-fields scoring method for the assessment of tumor budding in colorectal cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2013;26:295–301. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Punt CJ, Buyse M, Kohne CH, Hohenberger P, Labianca R, Schmoll HJ, et al. Endpoints in adjuvant treatment trials: a systematic review of the literature in colon cancer and proposed definitions for future trials. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 2007;99:998–1003. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohrling K, Karlberg M, Edler D, Hallstrom M, Ragnhammar P. A combined analysis of mismatch repair status and thymidylate synthase expression in stage II and III colon cancer. Clin. Colorectal. Cancer. 2013;12:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edler D, Glimelius B, Hallstrom M, Jakobsen A, Johnston PG, Magnusson I, et al. Thymidylate synthase expression in colorectal cancer: a prognostic and predictive marker of benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:1721–1728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis-correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;324:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Des Guetz G, Uzzan B, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Morere JF, Benamouzig R, et al. Microvessel density and VEGF expression are prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. Meta-analysis of the literature. Br. J. Cancer. 2006;94:1823–1832. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uzzan B, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Perret GY. Microvessel density as a prognostic factor in women with breast cancer: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Cancer. Res. 2004;64:2941–2955. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ostman A, Corvigno S. Microvascular mural cells in cancer. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:838–848. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou W, Chen C, Shi Y, Wu Q, Gimple RC, Fang X, et al. Targeting glioma stem cell-derived pericytes disrupts the blood-tumor barrier and improves chemotherapeutic efficacy. Cell. Stem. Cell. 2017;21:591–603 e594. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim J, de Sampaio PC, Lundy DM, Peng Q, Evans KW, Sugimoto H, et al. Heterogeneous perivascular cell coverage affects breast cancer metastasis and response to chemotherapy. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e90733. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.90733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tynninen O, Sjostrom J, von Boguslawski K, Bengtsson NO, Heikkila R, Malmstrom P, et al. Tumour microvessel density as predictor of chemotherapy response in breast cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer. 2002;86:1905–1908. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Punt CJ, Koopman M, Vermeulen L. From tumour heterogeneity to advances in precision treatment of colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017;14:235–246. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haddad FG, Eid R, Kourie HR, Barouky E, Ghosn M. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in nonmetastatic colorectal cancers. Future. Oncol. 2018;14:2097–2102. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roepman P, Schlicker A, Tabernero J, Majewski I, Tian S, Moreno V, et al. Colorectal cancer intrinsic subtypes predict chemotherapy benefit, deficient mismatch repair and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;134:552–562. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yothers G, O’Connell MJ, Lee M, Lopatin M, Clark-Langone KM, Millward C, et al. Validation of the 12-gene colon cancer recurrence score in NSABP C-07 as a predictor of recurrence in patients with stage II and III colon cancer treated with fluorouracil and leucovorin (FU/LV) and FU/LV plus oxaliplatin. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:4512–4519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author.