Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) has been considered an alternative process for intercellular communication. EVs release by filamentous fungi and the role of vesicular secretion during fungus-host cells interaction remain unknown. Here, we identified the secretion of EVs from the pathogenic filamentous fungus, Aspergillus fumigatus. Analysis of the structure of EVs demonstrated that A. fumigatus produces round shaped bilayer structures ranging from 100 to 200 nm size, containing ergosterol and a myriad of proteins involved in REDOX, cell wall remodeling and metabolic functions of the fungus. We demonstrated that macrophages can phagocytose A. fumigatus EVs. Phagocytic cells, stimulated with EVs, increased fungal clearance after A. fumigatus conidia challenge. EVs were also able to induce the production of TNF-α and CCL2 by macrophages and a synergistic effect was observed in the production of these mediators when the cells were challenged with the conidia. In bone marrow-derived neutrophils (BMDN) treated with EVs, there was enhancement of the production of TNF-α and IL-1β in response to conidia. Together, our results demonstrate, for the first time, that A. fumigatus produces EVs containing a diverse set of proteins involved in fungal physiology and virulence. Moreover, EVs are biologically active and stimulate production of inflammatory mediators and fungal clearance.

Keywords: extracellular vesicles, filamentous fungus, Aspergillus fumigatus, host-pathogen interactions, macrophages, neutrophils

Introduction

Intercellular communication is a crucial process that occurs from simple organisms, as bacteria, up to complex organisms, including mammals. Communication can happen by direct interaction between cells or by secretion of molecules that act directly to coordinate cellular functions (Nilsen-Hamilton and Hamilton, 1982; Yoon et al., 2014; Yáñez-Mó et al., 2015). Recently, the release of extracellular vesicles (EVs) has been associated with the process of intercellular communication (Yoon et al., 2014). EVs are structures secreted by cells and formed by a lipid bilayer membrane, forming a lumen containing a specific burden of biomolecules, for example, proteins, lipids, polysaccharides and nucleic acids (Yoon et al., 2014). Release of EVs offers simultaneous delivery of many different messenger molecules and may be able to reach sites distant from vesicular origin (Yáñez-Mó et al., 2015).

There is now substantial evidence to suggest that EVs may be key-mediators of the pathogenesis of infections caused by bacteria, parasites, virus and fungi (Joffe et al., 2016). These vesicles may cause host cell death, elicit immune response, and in some cases, confer protection against diseases (Brown et al., 2015). For example, in prokaryotes, molecules able to confer cytotoxicity to host cells, factors responsible for biofilm production and antibiotic resistance have been identified in EVs (Kuehn and Kesty, 2005). In Escherichia coli, α-hemolisin fractions were identified inside EVs and were shown to be relevant in red blood cells lysis (Balsalobre et al., 2006). Similarly, Staphylococcus aureus EVs may induce cytotoxicity and are able to induce apoptosis in vitro cells (Gurung et al., 2011). Mycobaterium tuberculosis EVs are able to stimulate the cytokine and chemokine in vitro production, and favor the pathogen infection in vivo model (Prados-Rosales et al., 2011).

It has been demonstrated that fungi are able to produce biologically active EVs under culture and during infection (Rodrigues et al., 2007; Albuquerque et al., 2008; Gehrmann et al., 2011; Vallejo et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2014; Bitencourt et al., 2018; Ikeda et al., 2018). The characterizations of fungal EVs revealed great variety of molecules with biological function as lipids, polysaccharides and nucleic acids. Besides that, it was also identified proteins known to participate in virulence, cellular metabolism, signal transduction, and nuclear and structure proteins (Albuquerque et al., 2008; Rodrigues et al., 2008; Oliveira et al., 2010; Vallejo et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2014, 2015; Brown et al., 2015; Gil-Bona et al., 2015; Vargas et al., 2015; Ikeda et al., 2018). For example, C. neoformans EVs are able to stimulate immunomodulatory mediators by phagocytes and increase fungal clearance (Oliveira et al., 2010). This immunomodulatory role was also observed in EVs released by C. albicans, in which the vesicles were able to stimulate innate and adaptive response and trigger an increase in fungal clearance (Vargas et al., 2015).

Of interest, most studies have characterized EVs in yeast, while the release and characterization of these structures in filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus fumigatus, have been poorly explored. A. fumigatus is a filamentous, ubiquitous and saprophytic fungus of significant medical importance to humans (Latgé, 1999). To the best of our knowledge, the production, secretion and function of EVs in A. fumigatus has not been described. Considering the capacity of EVs to contribute to the pathogenesis of various fungal infection, we characterized and investigated the immune effects of A. fumigatus EVs. Our results demonstrated that the EVs are released by A. fumigatus and their production is affected by the time of growth. We also identified that EVs are able to stimulate phagocytes and improve the phagocytic capacity and fungal clearance by these cells.

Materials and Methods

Culture Conditions

The A. fumigatus A1163 strain was used to EVs isolation. This strain is derived from A. fumigatus CEA17, a strain converted in pyrG+ by the insert of Aspergillus niger pyrG+ gene. CEA17 strain is a uracil auxotrophic strain from A. fumigatus clinical isolate CEA10 (Fedorova et al., 2008). To standardize EVs production, 1 × 107 conidia from A. fumigatus were inoculated in 50 mL of YG medium (0.5% w/v yeast extract powder; 2% w/v glucose; 0.1% v/v trace elements). Conidia were incubated for 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h under 120 rpm at 37°C. The mycelia was filtered in paper filter, then dried and weighed. After standardizing the time of culture, inoculums were made in 1 L of culture.

EVs Isolation

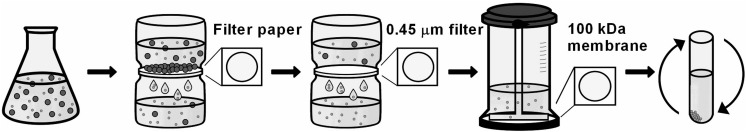

The isolation of EVs was performed according to Rodrigues and colleagues (Rodrigues et al., 2007), adapted. At each time point, the mycelium was separated from supernatant by filtration using paper filter. Supernatant was filtered using a 0.45 μm filter (Sartorius) and concentrated up to 25 mL Amicon ultra-concentration system (cutoff 100 KDa, Millipore). The concentrated supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C. The pellet of EVs was washed with phosphate-buffered saline 1X (PBS) and centrifuged in the same conditions. Pellet was resuspended in 260 μL PBS 1X, treated with Protease Inhibitor Cocktails 10X (Sigma) in 1:100 and stored at −80°C (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Experimental strategy to isolate EVs. 2 × 108 conidia/L were inoculated in YG media for 48, 72, 96, and 120 h at 37°C. After mycelium filtration with paper filter, the supernatant was filtered in a 0.45 μm membrane to retain reminiscent cells. Then, the flow-through was concentrated using a 100 kDa membrane. The supernatant was concentrated at 100,000 g to isolate the vesicles pellet.

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

Quantity and distribution of EVs size were measured by NTA, using the Nanosight appliance (Malvern Instruments) and NTA 3.0 software. NTA is a technic of optical dispersion to determine the distribution of size, in a nanometer scale, of particles in a solution. The appliance allows a direct individual light dispersion visualization of particles illuminated by a laser beam (Rupert et al., 2017).

Transmission Electronic Microscopy (TEM)

TEM was used to visualize the EVs from supernatant of A. fumigatus culture. Pellets obtained from six independent preparations were fixed with glutaraldehyde 2.5% v/v + 4% v/v formaldehyde in sodium cacodylate buffer 0.1 M; pH 7.2. Next, samples were washed in PBS and incubated for 60 min in 1% osmium, dehydrated in ethanol series, and embedded in Spurr’s resin. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were obtained in Leica UC7 ultramicrotome and contrasted with 5% w/v uranyl acetate for 20 min and 0.5% w/v lead citrate for 5 min. Samples were observed in a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV (Rodrigues et al., 2007; Albuquerque et al., 2008).

Proteins and Ergosterol Quantification

Proteins were quantified using Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad) at 595 nm, using a standard curve (5–30 μg/μL) of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). Ergosterol was quantified by modifications of Vargas and colleagues protocol (Vargas et al., 2015). Briefly, speedvac dried EVs were resuspended in 50 μL methanol. It was added 450 μL of chloroform, homogenated and centrifuged at 18,000 g for 5 min. The supernatant dried in speedvac and resuspended in 200 μL of absolute ethanol. The quantification was done by colorimetry using a calibration curve (0.5–1.024 μg/mL) of ergosterol, at 282 nm.

Animals

Experiments in mice were approved by the ethics committee (Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais CEUA-255/2018) of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). All experiments were performed in accordance with international guidelines and regulations. Ten to twelve weeks mice C57BL/6 were infected with 2 × 107 conidia of A. fumigatus A1163, once a week, during 3 weeks. One week after the last infection, serum of animals was obtained and stored at −20°C. Animals were euthanized in order to remove tibia and fibula bones. These bones were washed with RPMI medium in order to obtain bone-marrow for neutrophils isolation. The content was centrifuged at 430 g for 10 min at 4°C. After that, red blood cells were lysed with ACK Lysis buffer and cells were centrifuged again in the same conditions. Histopaque 1077-1 (Sigma) (1:1) was used to separate the polymorphonuclear cells, prior to their centrifugation at 430 g for 30 min at 4°C.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

Two μg of proteins of EVs were resuspended in sample buffer (Tris-HCl 0.5 M; Glycerol; SDS 10% w/v; β-mercaptoethanol; blue of bromofenol), and resolved in SDS-PAGE 12%. The total proteins profile was stained by silver.

For immunoblotting, 2 μg of proteins of EVs were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with 5% w/v skimmed milk the membrane was incubated with serum from mice stimulated with A. fumigatus (1:10). After overnight incubation, anti-mouse IgG-HRP secondary antibody (Santa Cruz) was added for 1 h in room temperature. The membrane revealed with Luminata solution (Luminata Classico Western HRP Substrate, Millipore). Cropping, faint background, contrast and colors edition were done using Photos software from Windows 10.

Proteomic Analysis by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry

The lyophilized samples digested using ProteaseMAX stock (Promega) and 2 μg of trypsin. After digestion with trypsin was used μ-C18 ZipTip (Merck Millipore) for cleaning up peptide samples. After, the samples were dried in speedvac and used for the analysis.

An Easy-nLC 1200 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Corp., Waltham, MA, United States) was coupled to an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos instrument equipped with a nanospray source (Thermo Fisher Scientific Corp., Waltham, MA, United States). Nano-LC solvents were water with 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile: water (80:20) with 0.1% formic acid (B) and the flow rate was 300 nL/min. Samples (3 μL) were injected onto a trapping column (Acclaim PepMap 0.075 mm, 2 cm, C18, 3 μm, 100 A; Thermo) in line with a Nano-LC column (Acclaim PepMap RSLC (0.075 mm, 15 cm, C18, 2 μm, 100 A; Thermo). The sample was loaded in the trap column and washed with 20 μL of solvent A at constant pressure (500 bar). After that, the sample was eluted to the column using a flow of 300 nL/min.

MS/MS analyses were conducted in the ESI+ mode. The instrument settings included the spray voltage at 1950 kV, capillary temperature at 300°C, and S-Lens RF level at 30%. A full-scan event was performed in profile mode over the mass range of m/z 400–1600 at a resolution of 120,000 followed by MS/MS analyses in a cycle time of 3 s. High-collision dissociation (HCD) with a normalized collision energy set at 30% was used for fragmentation. The resulting MS/MS fragment ions were detected in the mass range of m/z 100–2000 using the Orbitrap mass analyzer at a resolution of 30,000 using centroid mode. An AGC target of 5e4 and a maximum injection time of 54 ms were used.

A. fumigatus databank available at UniProt1 were loaded into MaxQuant (Tyanova et al., 2016) and used to identify the protein content on EVs. A combined list of proteins identified in all independent replicates (n = 3) were generated.

Phagocytic and Clearance Ability of Immune Cells After Stimulation With Vesicles

Macrophages RAW 264.7 were cultivated in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM), supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum 10% v/v (FBS). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. 5 × 104 macrophages were stimulated for 5 h with A. fumigatus EVs in a final amount of 0.1; 0.2; or 0.4 μg of proteins. After stimulation period, 5 × 105 conidia of A1163 strain (Multiplicity of Infection – MOI 10:1) were added to cell culture. Content of wells was collected after 6 h of stimulus. Macrophages were washed with 1X PBS to remove the non-phagocyted conidia, lysed with sterile water, and conidia were plated in YAG medium to quantify the colony forming units (CFU).

To evaluate phagocytosis, 5 × 104 macrophages were stimulated for 5 h with EVs in a final amount of 0.4 μg of proteins. 5 × 105 conidia of A1163 strain (MOI 10:1) were added to cell culture. After 4 and 6 h of stimulus, supernatant was collected, cells were stained with Quick Panoptic (Laborclin).

The capacity of fungal clearance by cells stimulated with EVs was also evaluated in neutrophils. 5 × 105 neutrophils (BMDN) were stimulated for 3 h with EVs in a final amount of 0.4 μg of proteins, at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. 5 × 105 conidia (MOI 1:1) were added to culture of cells. After 3 h of challenge, content of wells was collected, neutrophils were lysed with sterile water and the reminiscent conidia were plated in YAG medium to quantify the CFU.

To evaluate phagocytosis, 5 × 105 neutrophils were stimulated for 3 h with EVs (0.4 μg of proteins). 2.5 × 106 conidia of A1163 strain (MOI 5:1) were added to neutrophil culture. After 3 h, supernatant was collected and submitted to a citospin for 5 min at 35 g, the slides were stained with Quick Panoptic (Laborclin). Non-stimulated cells, cells stimulated only with EVs and cells challenged only with the fungus were used as control.

Confocal Microscopy

5 × 105 macrophages RAW 264.7 were plated in a 24 wells plate. The cells were incubated with CellMask Green (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in order to stain them, at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, for 10 min. A. fumigatus EVs were treated with 3 μM of DilC18 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h. EVs were washed one time with PBS 1X, resuspended in DMEM medium and co-incubated with macrophages for 30 min (Nicola et al., 2009; Oliveira et al., 2010). After this period, well was washed 3 times with DMEM medium and the slice submitted to confocal microscopy (4X zoom, increase of 20X).

Cytokines Measurement

Supernatant of cells stimulated with EVs and challenged with A. fumigatus were obtained and the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokine TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, and CCL2, and the modulatory cytokine IL-10 were evaluated, according to manufacturer instructions (R&D Systems).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences among experimental groups were determined by one way analysis of variance (One Way-ANOVA), followed by Tukey post-test. Results involving two experimental groups were analyzed by t Student test. All data was considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. Statistical analysis were realized using the GraphPad Prism 6 software.

Results

A. fumigatus Produce EVs During Growth

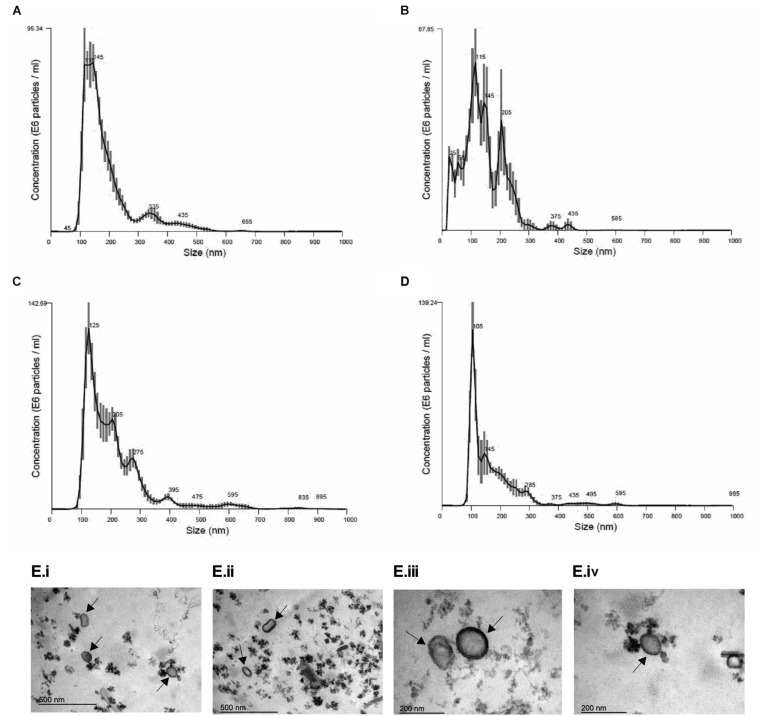

In order to establish conditions of growth and production of EVs, we analyzed different culture time points (24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h at 37°C). It was observed that fungal mass increased exponentially until 72 h and the growth speed decreased after that (Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting this time point was the beginning of the stationary phase. Based on the A. fumigatus growth curve, we analyzed the size and yield of EVs production. We observed that the yield of EVs production was similar in all time points (Table 1). Besides that, A. fumigatus produced a majority amount of EVs with average size between 100 and 200 nm and a minor population of EVs varying from 300 to 595 nm (Figures 2A–D). Further experiments were conducted using fungi collected at 48 h of culture, as this was optimal in terms of growth, time of incubation and yield. Using these 48 h cultures, Transmission Electronic Microscopy (TEM) analysis revealed the presence of spherical structures displaying electrodense bilayers, characteristics of EVs. Quantification showed that these isolated EVs had the same average diameter as demonstrated by NTA (Figure 2E).

TABLE 1.

Concentration of EVs released by A. fumigatus in different periods of culture.

| NTA analysis | |

| Period of culture (h) | Concentration (particles/mL) |

| 48 | 8.56 × 109 ± 3.76 × 108 |

| 72 | 8.91 × 109 ± 4.91 × 108 |

| 96 | 1.33 × 1010 ± 3.51 × 108 |

| 120 | 6.67 × 109 ± 3.93 × 108 |

FIGURE 2.

Morphological and dimensional aspects of A. fumigatus EVs. Dimensional analysis of EVs in 48 h (A), 72 h (B), 96 h (C), and 120 h (D) of culture. EVs were isolated and observed by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis – Nanosight (Malvern). E6 particles means 106 particles. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) of EVs isolated by ultracentrifugation of 48 h culture supernatants from A. fumigatus (E). Scale bar 500 nm (i,ii) and 200 nm (iii,iv). Arrows indicate EVs.

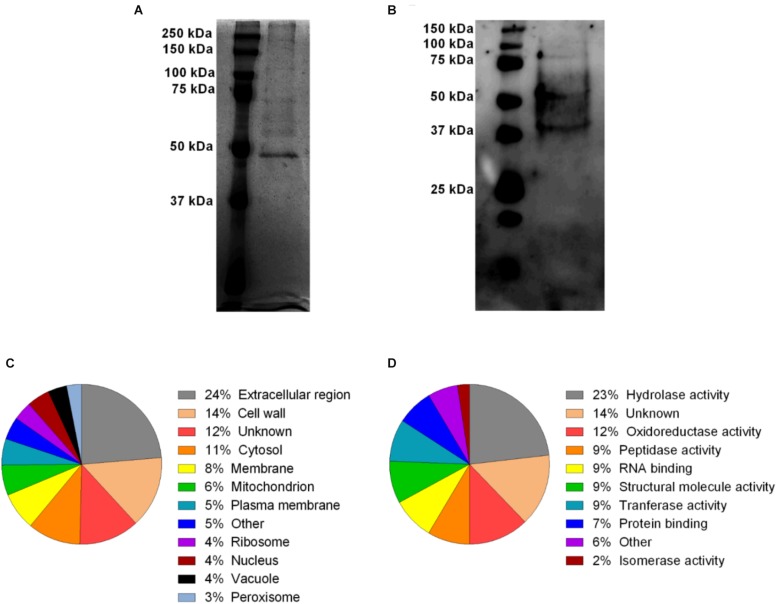

A. fumigatus EVs Composition

In order to investigate the profile of protein content in A. fumigatus EVs, a silver stained SDS-PAGE was performed. Figure 3A shows the electrophoretic resolved profile of protein content in the EVs demonstrating at least 9 major bands of proteins varying from 50 to 250 KDa (Supplementary Figure S2). These proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with total serum obtained from mice previously infected with A. fumigatus. Serum reactive proteins of approximately 37–150 kDa were found in A. fumigatus EVs (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S3).

FIGURE 3.

A. fumigatus EVs protein diversity and Gene Ontology categorization of MS identified proteins. The content of proteins (2 μg) in the vesicles was visualized by silver staining (A). Some of these proteins were reactive in the presence of total anti-serum from previously infected mice (B). Proteins were identified by mass spectrometry and classified according to their subcellular predicted localization (C) and molecular predicted function (D).

Considering that the protein profile in A. fumigatus EVs is unknown, the protein composition was identified using proteomics. According to our analysis, 60 proteins were identified (Table 2). The cellular composition and the molecular and biological functions proposed for these proteins are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Using the UniProt2 and AspGD3 databases, proteins were classified according to their predicted cellular localization and molecular putative functions in the fungal cells (Figures 3C,D), and included hydrolases, oxydoreductase, peptidases, tranferases, RNA/carbohydrate/protein binding, structural activity, isomerases and phosphatases. The proteins were also classified according to cellular localization. The identified proteins were associated to the extracellular region (24%), cell wall (14%), cytosol (11%), membrane (8%), mitochondrion (6%), plasma membrane (5%), ribosome (4%), nucleus (4%), vacuole (4%) and peroxisome (3%) (Figure 3C). The proteins were also classified according to their biological function. The majority of vesicular proteins classified were associated to carbohydrate metabolic processes and response to cellular stress, and also to proteins associated to pathogenesis (Supplementary Table S1). The presence of proteins with antigenic potential, in association with pathogenesis and host response stimulation in EVs proteome, led us to investigate if the A. fumigatus EVs were able to stimulate macrophages and neutrophils, as competent phagocytes.

TABLE 2.

List of protein groups identified by proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicles from A. fumigatus.

| Protein group number | A. fumigatus genome database acession number | Protein name |

| 1 | AFUB_063700 | Glutamate dehydrogenase |

| 2 | AFUB_016770 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 3 | AFUB_063890 | Ecm33 |

| 4 | AFUB_096050 | Allergen Asp F3 (Peroxiredoxin family protein) |

| 5 | AFUB_037910 | Ubiquitin (UbiC), putative |

| 6 | AFUB_015530 | Extracellular cell wall glucanase Crf1/allergen Asp F9 |

| 7 | AFUB_066130 | Aminopeptidase |

| 8 | AFUB_094680 | FAD/FMN-containing isoamyl alcohol oxidase MreA |

| 9 | AFUB_094730 | IgE-binding protein, putative |

| 10 | AFUB_097210 | Carboxypeptidase |

| 11 | AFUB_095500 | GPI anchored protein, putative |

| 12 | AFUB_005920 | Glycogenin |

| 13 | AFUB_002680 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 14 | AFUB_099560 | Tripeptidyl-peptidase (TppA), putative |

| 15 | AFUB_004489 | FG-GAP repeat protein, putative |

| 16 | AFUB_045170 | Cell wall protein phiA |

| 17 | AFUB_048140 | Extracellular phytase, putative |

| 18 | AFUB_020900 | Allergen Asp F4 |

| 19 | AFUB_022370 | 1,3-beta-glucanosyltransferase gel4 |

| 20 | AFUB_052010 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase |

| 21 | AFUB_052060 | Thioredoxin reductase, putative |

| 22 | AFUB_052270 | Class III chitinase ChiA1 |

| 23 | AFUB_050860 | Major allergen Asp F1 |

| 24 | AFUB_052690 | Molecular chaperone Mod-E/Hsp90 |

| 25 | AFUB_085650 | Endo-chitosanase |

| 26 | AFUB_046050 | Alpha,alpha-trehalose glucohydrolase TreA/Ath1 |

| 27 | AFUB_048180 | Probable glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase eglC |

| 28 | AFUB_047510 | Extracellular conserved serine-rich protein |

| 29 | AFUB_047560 | FAD-dependent oxygenase, putative |

| 30 | AFUB_037350 | Phosphoglucomutase PgmA |

| 31 | AFUB_050510 | BYS1 domain protein, putative |

| 32 | AFUB_040810 | Aspartyl aminopeptidase |

| 33 | AFUB_010890 | 1,3-beta-glucanosyltransferase Bgt1 |

| 34 | AFUB_023440 | 60S ribosomal protein L18 |

| 35 | AFUB_018250 | 1,3-beta-glucanosyltransferase gel1 |

| 36 | AFUB_009540 | Adenosylhomocysteinase |

| 37 | AFUB_066060 | GPI anchored cell wall protein, putative |

| 38 | AFUB_087520 | Isoamyl alcohol oxidase, putative |

| 39 | AFUB_006000 | 40S ribosomal protein S3, putative |

| 40 | AFUB_004410 | Ubiquitin UbiA, putative |

| 41 | AFUB_079620 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 42 | AFUB_050490 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| 43 | AFUB_023550 | Probable Xaa-Pro aminopeptidase pepP |

| 44 | AFUB_005160 | Probable NAD(P)H-dependent D-xylose reductase xyl1 |

| 45 | AFUB_036480 | Putative UDP-galactopyranose mutase |

| 46 | AFUB_034560 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 47 | AFUB_093550 | Actin Act1 |

| 48 | AFUB_021670 | ER Hsp70 chaperone BiP, putative |

| 49 | AFUB_006770 | Elongation factor 1-alpha |

| 50 | AFUB_056780 | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] |

| 51 | AFUB_007770 | Molecular chaperone Hsp70 |

| 52 | AFUB_009760 | Phosphoglycerate kinase |

| 53 | AFUB_036860 | 60S ribosomal protein L22, putative |

| 54 | AFUB_025910 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P2/allergen Asp F 8 |

| 55 | AFUB_017890 | Purine nucleoside permease, putative |

| 56 | AFUB_000660 | CFEM domain protein |

| 57 | AFUB_089500 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 58 | AFUB_070900 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 59 | AFUB_024920 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase 5 |

| 60 | AFUB_001190 | Ribosomal protein S13p/S18e |

Ergosterol is the main lipid in fungal membranes and its content is also important to maintain plasma membrane integrity in EVs. Results demonstrated that in 1.5 × 1010 A. fumigatus EVs particles there were 13.5 μg of ergosterol.

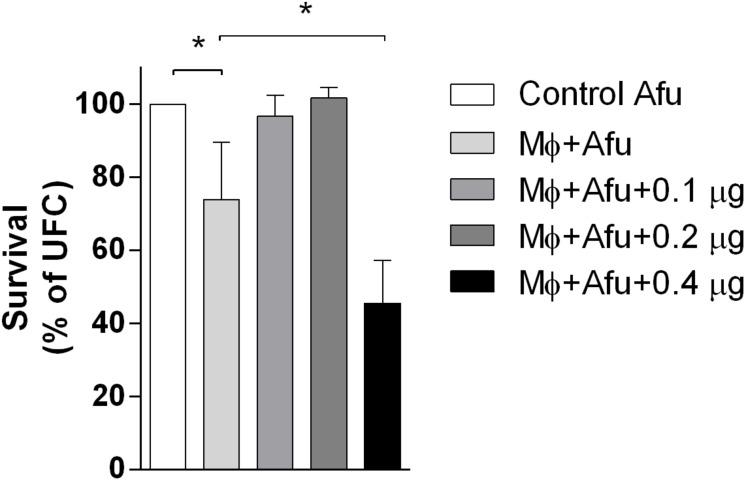

A. fumigatus EVs Are Recognized by Macrophages and Promote an Increase of Fungicide Capacity and Production of Inflammatory Mediators

EVs are known to modulate host responses and function as virulence factors. In order to identify the effects of A. fumigatus EVs in phagocytes, macrophages were stimulated with different amounts of EVs and challenged with A. fumigatus. Results demonstrated that 0.1 and 0.2 μg of EVs (measured as total protein content) were not able to induce A. fumigatus clearance by macrophages (Figure 4). However, 0.4 μg of EVs were very effective in stimulating the clearance of conidia by macrophages, leading to more than 50% killing of conidia after challenge. When compared to the positive control, the stimulation of phagocytes with 0.4 μg of EVs was able to double the killing effector functions of macrophages (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

A. fumigatus killing by macrophages. 5 × 104 RAW 264.7 macrophages were stimulated with 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 μg of EVs (measured as total protein content) for 5 h. After that, the macrophages were challenged with 5 × 105 (MOI 10:1) conidia of A. fumigatus for 6 h. The amount of live conidia was quantified in YG media as unit forming colony (UFC). Data are representative of three experiments. ∗ Represents statistically differences between the indicated groups (p < 0.05) as determined by One Way-ANOVA.

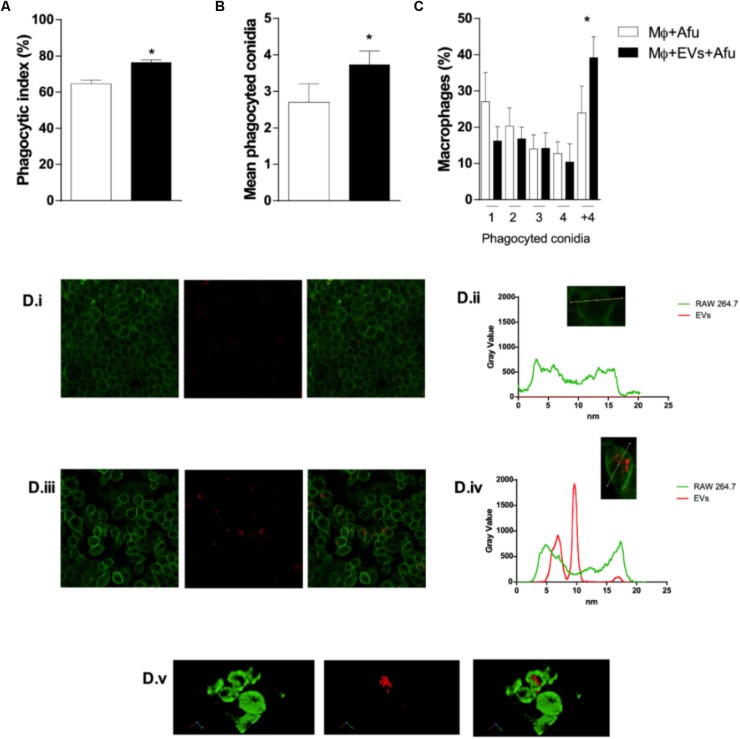

In order to verify whether the mechanisms of fungal recognition and internalization by macrophages were affected by EVs, the phagocytic capacity of macrophages previously stimulated with A. fumigatus EVs was evaluated. After 5 h incubation, results demonstrate that EVs were able to increase phagocytosis by approximately 12% in comparison to macrophages not exposed to EVs (Figure 5A). In addition, complementary analysis showed that the number of phagocyted conidia in the EVs stimulated macrophages was higher than in the control group (Figure 5B). Macrophages from both groups (non-EVs or EVs stimulated) demonstrated an equivalent phagocytic capacity, in terms of internalizing 1, 2, 3, or 4 conidia per macrophage. On the other hand, the presence of EVs was able to induce macrophages capacity to internalize conidia as seen by an increase of almost 50% in the number of macrophages with more than 4 fungal cells inside cells (Figure 5C).

FIGURE 5.

EVs are able to modulate A. fumigatus phagocytosis. 5 × 104 macrophages were stimulated with EVs for 5 h. Then, the macrophages were challenged with 5 × 105 (MOI 10:1) conidia of A. fumigatus for 4 h and the phagocytosis was evaluated (A), the average number of phagocyted conidia by cells (B), and the mean number of conidia phagocyted per macrophage (C). DiIC18 (red)-stained vesicles were incubated with macrophages (D). The plasma membrane was stained with CellMask (green). Control microscopy shown macrophages stained by CellMask without vesicles (i); densitometry of a single cell (macrophage) stained by Cellmask (ii); microscopy shown macrophages stained by CellMask incubated with DiLC18 stained vesicles (iii); densitometry of a single cell (macrophage) stained by CellMask showing EVs in the cytoplasm (iv). Co-localization of macrophages and vesicles in merged images (v). (3D reconstruction). Data are representative of three experiments. ∗Represents statistically differences between the indicated groups (p < 0.05) as determined by One Way-ANOVA and two-sample independent t-tests.

The phagocytosis of EVs by macrophages was observed under confocal microscopy. Images show that there were vesicles outside and inside macrophages. 3D reconstitution of images demonstrated that EVs were in the cytoplasm of macrophages, confirming their internalization (Figures 5Di–v and Supplementary Movie S1).

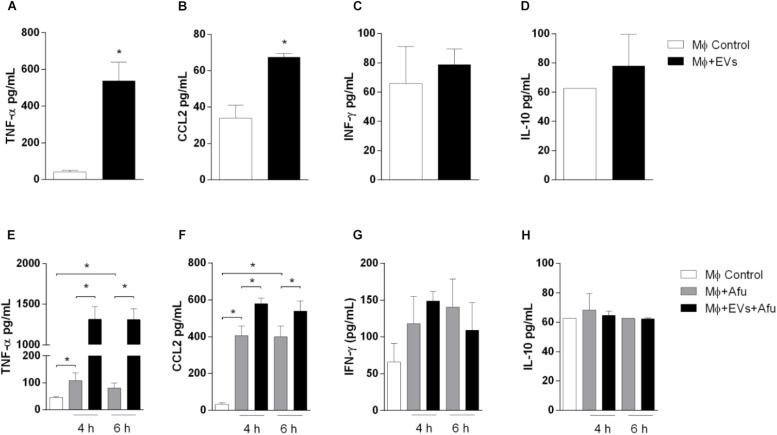

Considering that EVs are able to increase the uptake of the fungus by macrophages, levels of inflammatory mediators produced by EVs stimulation were evaluated. After 5 h stimulation, EVs were able to induce significant secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-α (approximately 10 times) and a twofold change in CCL2 levels compared to non-stimulated cells (Figures 6A,B). Results demonstrated no changes in IFN-γ levels and IL-10, after EVs stimulation (Figures 6C,D).

FIGURE 6.

EVs are able to stimulate cytokines and chemokines production by macrophages. 5 × 104 macrophages were stimulated with 0.4 μg of A. fumigatus EVs. Secretion of inflammatory mediators TNF-α (A), CCL2 (B), IFN-γ (C), and IL-10 (D) were quantified. Cells pre-incubated with EVs were challenged with 5 × 105 (MOI 10:1) conidia of A. fumigatus for 4 and 6 h. Production of inflammatory mediators TNF-α (E), CCL2 (F), IFN-γ (G), and IL-10 (H), during in vitro challenge with A. fumigatus, were quantified. Data are representative of three experiments. ∗Represents statistically differences between the indicated groups (p < 0.05) as determined by One Way-ANOVA and two-sample independent t-tests.

We analyzed the production of cytokines during in vitro A. fumigatus infection. Results demonstrate that EVs stimulation prior to fungal challenge is responsible for an increase of approximately 15 times in the production of TNF-α (Figure 6E). The levels of the chemokine CCL2 were also increased, around 30%, when compared to non-EVs control group (Figure 6F). No differences were observed in IFN-γ and IL-10 levels (Figures 6G,H).

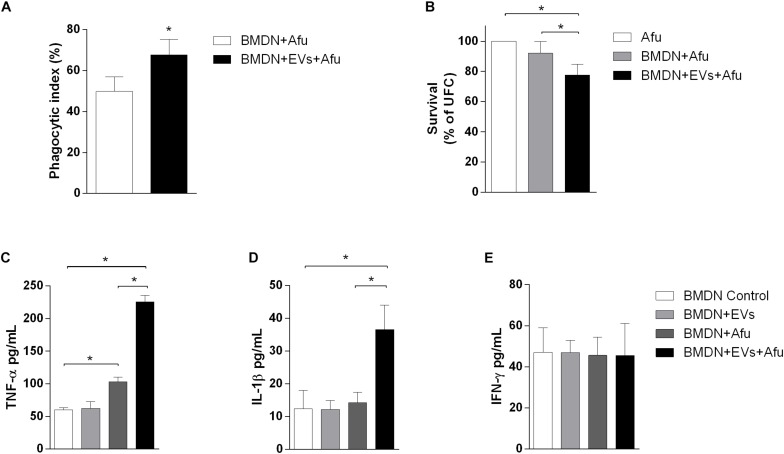

EVs Promote an Increase in Fungicide Capacity by Neutrophils and Enhance Cytokine Production After A. fumigatus Challenge

Neutrophils are recruited in response to A. fumigatus challenge (Dagenais and Keller, 2009; Muller, 2013). We investigated the capacity of EVs to stimulate bone marrow-derived neutrophils (BMDN) and to improve their fungicide capacity. After 3 h of EVs stimulation, there was a pattern of response similar to that of macrophages. EVs stimulation could enhance phagocytic capacity by approximately 17% when compared to the control non-EVs group (Figure 7A). This effect was accompanied by induction of fungal clearance by BMDN (Figure 7B). Together, these results show that the sensitization of phagocytes with A. fumigatus EVs was able to prime these cells and increase their phagocytic capacity, hence culminating in higher fungal clearance.

FIGURE 7.

Fungicide capacity and cytokines production by neutrophils. 5 × 105 bone marrow-derived neutrophils were challenged with 2.5 × 106 (MOI 5:1) (A) or 5 × 105 (MOI 1:1) conidia (B), and the phagocytosis (A) and fungal killing (B) were evaluated after 3 h of incubation. Production of TNF-α (C), IL-1β (D), and IFN-γ (E) was evaluated in BMDN stimulated with EVs and challenged with A. fumigatus. Data are representative of three experiments. ∗Represents statistically differences between the indicated groups (p < 0.05) as determined by One Way-ANOVA and two-sample independent t-tests.

Considering that the EVs were able to induce the production of inflammatory mediators by macrophages, we also evaluated the capacity of these structures to stimulate cytokine production in BMDN. After 3 h of stimulus, EVs were not able to induce TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ production (Figures 7C–E, respectively). On the other hand, results demonstrated that stimulation with EVs induced an increase of TNF-α and IL-1β production after fungal challenge. Levels of IFN-γ did not change after challenge (Figures 7C–E).

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrated for the first time the release of EVs by the pathogenic filamentous fungus, A. fumigatus. Considering that the liberation of EVs can happen in both the saprophytic phase or during the colonization of mammal hosts, different in vitro growth conditions could interfere with EVs production. In this sense, we analyzed several culture time points to determine the ideal condition to isolate the EVs released by A. fumigatus. The exponential phase of fungal growth is the period of highest metabolic activity of cells (Brown et al., 2015). According to our data and the literature, this time point for A. fumigatus comprises up to 72 h, when the stationary phase begins (Meletiadis et al., 2001; Reeves et al., 2004). Considering the growth of the fungus and that the production of EVs was similar at 48 and 72 h, 48 h of incubation was chosen as the optimal point to carry out the functional characterizations of A. fumigatus EVs.

In all A. fumigatus growing conditions two main populations of vesicles were identified, one major population constituted by small vesicles with size between 100 and 200 nm diameter and a minor population of vesicles up to 595 nm. Variations in the diameters of isolated EVs may indicate that different pathways may be important in their biogenesis. Our findings are consistent with the diameter of EVs observed in other fungi such as in H. capsulatum, C. neoformans, and P. brasiliensis (Rodrigues et al., 2007; Albuquerque et al., 2008; Vallejo et al., 2011; Baltazar et al., 2016). Other A. fumigatus strains probably release EVs with differences in size and consequently in composition, once it was already demonstrated that EVs released by different C. neoformans strains showed different protein composition. In C. albicans the EVs population can vary from 50 to 100 nm up to larger populations from 450 to 850 nm or 350 to 450 nm depending on the strain, and also showed differences in their protein content, demonstrating that fungal EVs are considered heterogeneous among species (Albuquerque et al., 2008; Vargas et al., 2015). The differences in EVs using other A. fumigatus strains will be investigated in future studies.

Secretion of EVs is considered an important vehicle of molecule transportation to the extracellular environment. The importance of EVs as a way of transportation is sustained by the fact that a great number of proteins have been identified in pathogenic fungi EVs. A variety of functions have been associated with these identified proteins, as biofilm formation, cell wall organization and remodeling, carbohydrates, lipids and protein metabolism, cell response to drugs, heat shock proteins, transport and vesicular fusion and antioxidants (Albuquerque et al., 2008; Rodrigues et al., 2008; Vargas et al., 2015; Zarnowski et al., 2018). In this work it was demonstrated that A. fumigatus EVs proteins were recognized by total serum antisera from previously A. fumigatus infected mice, suggesting that proteins of A. fumigatus transported by EVs are antigenic and sensitize host immune system. Similar findings have been reported for other fungal species, such as H. capsulatum, C. neoformans, P. brasiliensis, and C. albicans (Albuquerque et al., 2008; Rodrigues et al., 2008; Vallejo et al., 2011; Vargas et al., 2015).

The characterization of the proteins inside EVs identified proteins involved in metabolic processes, filamentous growth, sporulation, cell cycle and transport. Most of the proteins were classified as hydrolases. The presence of proteins that are able to hydrolyze the components of cell wall is interesting, once they can promote the remodeling of cell wall allowing the secretion of EVs (Albuquerque et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2015). Among proteins involved in cell wall remodeling in A. fumigatus, we identified the presence of glucanosyltransferases (Gel1, Gel4, and Bgt1), Ecm33 and EglC that participate in the elongation of cell wall glucan chain leading to maintenance and resistance of cell wall, suggesting that these proteins in the EVs participate of mechanisms of fungal growth (Chabane et al., 2006; Gastebois et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2013; Champer et al., 2016).

Many proteins were predicted to localize in the intracellular or extracellular space, suggesting that these vesicles are serving as a mechanism of transport for proteins beyond cells. Some identified proteins, as nucleoside diphosphate kinase and superoxide dismutase, have an important role in A. fumigatus polarization growth and in the resistance to high temperatures (Momany et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2003; Lambou et al., 2010; Dinamarco et al., 2012). These proteins are also involved in the pathogenesis and host response activation. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase plays a key role in resistance to oxidative stress. It was demonstrated in Neurospora crassa that a knockout mutant for this protein showed hypersensitivity to oxidative and thermal stress (Yoshida et al., 2006). Superoxide dismutase detoxifies superoxide reactive anions and contributes to oxidative burst inhibition. A. fumigatus SODs knockout mutants showed sensitivity to higher temperatures and ROS donors and their clearance by in vitro macrophages were higher than the wild type (Holdom et al., 2000; Lambou et al., 2010). In the same way, the thioredoxin reductase is able to inhibit the respiratory burst in neutrophils by breaking the NADPH oxidase, facilitating the fungus dissemination (Tsunawaki et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2012).

Chaperones are involved in morphogenesis, stress response (temperature and pH), osmolarity and antifungal resistance. This family of proteins were also identified in EVs of others fungi, such as C. neoformans, H. capsulatum, and C. albicans (Albuquerque et al., 2008; Rodrigues et al., 2008; Vargas et al., 2015) and are related to virulence and resistance to antifungals (Cordeiro et al., 2016; Cleare et al., 2017; O’Meara et al., 2017). HSP90 is an essential component of cytoplasmic chaperone network HSP70-HSP90 responsible for protein folding. Besides that, HSP90-calcineurin pathway have a crucial role in the antifungal resistance (Soriani et al., 2008; O’Meara and Cowen, 2014; Tiwari et al., 2015).

Other components of significant relevance to A. fumigatus virulence are proteins known to possess significant allergenic properties in the host. In the EVs of A. fumigatus the allergens Asp f-1, Asp f-3, Asp f-4, Asp f-8, and Asp f-9 were identified. The ribotoxin Asp f-1 is able to reach the cytosol of mammalian host cells and inactivate the ribosomes inhibiting the proteins synthesis (Olmo et al., 2001; Lacadena et al., 2007). Asp f-3 is a peroxiredoxin able to bind IgE and inactivate ROS (Ramachandran et al., 2002; Hillmann et al., 2016). Asp f-4 is also one of the main antigens of A. fumigatus, with unknown function, and it is used as a marker for diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) (Kurup et al., 2000). Together, these data suggest that the milieu of proteins in A. fumigatus EVs have a role in invasion, resistance and host fungus growth, demonstrating that EVs secretion may be related to virulence of A. fumigatus.

Studies with EVs of pathogenic microorganisms demonstrate that EVs are able to interfere with a proper immune response. A. fumigatus EVs increased fungal killing by phagocytes and this property is in accordance with results described for EVs derived from C. neoformans (Oliveira et al., 2010), Trichophyton interdigitale (Bitencourt et al., 2018), S. aureus (Choi et al., 2015), and C. albicans in a Galleria mellonella larva model of infection (Vargas et al., 2015). Together, these and our study show that EVs are immunologically active and have a potential to interfere with the course of infection, in general causing higher clearance of the pathogen after stimulation with the vesicles. These findings were unexpected as the fungus would be spending a considerable amount of energy producing EVs with proteins that do no favors its relation with host cells. However, these same protein may be associated with fungal growth and communication and enhancement of immune responses could be an unwanted effect (to the fungus) of secreted EVs. Further studies, however, are necessary to fully characterize the role of these EVs for fungal physiology and during in vivo infection, where multiple interactions between various cell types may occur.

The immunomodulatory components of EVs from pathogens indicate that the molecules associated to EVs can promote survival and dissemination of these organisms. On the other hand, they can also stimulate host immune response for pathogen clearance. The exact role of EVs derived from pathogens in the host-pathogen interactions probably depends on the development stage of the pathogens, environmental conditions and/or specific tissue (Schorey et al., 2015; Kuipers et al., 2018). In our work, we identified that the components present in A. fumigatus EVs have potential in stimulating an in vitro pro-inflammatory response, and increasing the capacity of clearance of the fungus.

Exposure of phagocytic cells to A. fumigatus was able to induce inflammatory mediators production, and interestingly, cells previously stimulated with EVs showed an additive effect in production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and CCL2. In A. fumigatus infections, TNF-α is a critical component of the innate immune response, as its signaling deficiency is able to result in a decrease of neutrophil influx and increase in mortality of infected animals. The administration of a TNF-α agonist, prior to infection with A. fumigatus, is able to increase the survival of mice (Mehrad et al., 1999). CCL2 is one of the main chemoattractant molecules regulating innate immunity, and it is positively regulated during in vitro challenge by A. fumigatus. The administration of anti-CCL2 serum in mice was able to decrease the clearance of conidia and increase the hyper-reactivity into the airways of mice infected with A. fumigatus (Blease et al., 2001; Loeffler et al., 2009).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we demonstrated that A. fumigatus produce EVs that are rich in a range of bioactive proteins. EVs production is affected by different environmental conditions, which suggests that these structures can have an important function during growth. EVs can be recognized by phagocytes and stimulate phagocytosis and production of pro-inflammatory mediators and impact on fungal clearance.

Data Availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

Animal Subjects: The animal study was reviewed and approved by Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais (CEUA), 255/2018, of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG).

Author Contributions

FS conceived the study. JS and FS designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. JS, LB, VC, LG-E, AO, WD, MR, KM, and IM performed the experiments. JS, LB, VC, LG-E, AO, WD, KM, IM, and FS interpreted the results and analyzed the data. LB, VC, LG-E, AO, WD, KM, IM, DAS, FF, DGS, MT, and FS contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais for the opportunity to develop this work. We are thankful to Ilma Marçal S., Rosemeire A. Oliveira, Jamil S. de Oliveira, Grazielle C. Florentino, and Eneida Paganini V. for technical support. We are grateful to Maria Isabel M. C. Guedes and Ricardo T. Gazzineli for ultracentrifuge and Gustavo B. Menezes for confocal microscopy.

Funding. This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (474528-2012-0 and 483184-2011-0) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (APQ-01756-10, APQ-02198-14, and APQ-03950-17). This study was funded in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) (Finance Code 001), Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia em Dengue e Interação Microrganismo Hospedeiro (INCT em Dengue), and Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02008/full#supplementary-material

References

- Albuquerque P. C., Nakayasu E. S., Rodrigues M. L., Frases S., Casadevall A., Zancope-oliveira R. M., et al. (2008). Vesicular transport in Histoplasma capsulatum: an effective mechanism for trans-cell wall transfer of proteins and lipids in ascomycetes. Cell. Microbiol. 10 1695–1710. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01160.x.Vesicular [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsalobre C., Silván J. M., Berglund S., Mizunoe Y., Uhlin B. E., Wai S. N. (2006). Release of the type I secreted α-haemolysin via outer membrane vesicles from Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 59 99–112. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04938.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltazar L., Nakayasu E. S., Sobreira T. J., Choi H., Casadevall A., Nimrichter L., et al. (2016). Antibody binding alters the characteristics and contents of extracellular vesicles released by Histoplasma capsulatum. mSphere 1:e00085-15. 10.1128/mSphere.00085-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitencourt T. A., Rezende C. P., Quaresemin N. R., Moreno P., Hatanaka O., Rossi A., et al. (2018). Extracellular vesicles from the Dermatophyte Trichophyton interdigitale modulate macrophage and keratinocyte functions. Front. Immunol. 9:2343. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blease K., Mehrad B., Lukacs N. W., Kunkel S. L., Standiford T. J., Hogaboam C. M. (2001). Antifungal and airway remodeling roles for murine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CCL2 during pulmonary exposure to Asperigillus fumigatus conidia. J. Immunol. 166 1832–1842. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L., Wolf J. M., Prados-Rosales R., Casadevall A. (2015). Through the wall: extracellular vesicles in Gram-positive bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13 620–630. 10.1038/nrmicro3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabane S., Sarfati J., Ibrahim-Granet O., Du C., Schmidt C., Mouyna I., et al. (2006). Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored Ecm33p influences conidial cell wall biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 3259–3267. 10.1128/aem.72.5.3259-3267.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champer J., Ito J. I., Clemons K. V., Stevens D. A., Kalkum M. (2016). Proteomic analysis of pathogenic fungi reveals highly expressed conserved cell wall proteins. J. Fungi 2:6. 10.3390/jof2010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. J., Kim M. H., Jeon J., Kim O. Y., Choi Y., Seo J., et al. (2015). Active immunization with extracellular vesicles derived from Staphylococcus aureus effectively protects against staphylococcal lung infections, mainly via Th1 cell-mediated immunity. PLoS One 10:e0136021. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleare L. G., Zamith-Miranda D., Nosanchuk J. D. (2017). Heat shock proteins in Histoplasma and Paracoccidioides. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 24:e00221-17. 10.1128/CVI.00221-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro R. A., Evangelista A. J. J., Serpa R., Marques F. J. F., Melo C. V., Oliveira J., et al. (2016). Inhibition of heat-shock protein 90 enhances the susceptibility to antifungals and reduces the virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii species complex. Microbiology 162 309–317. 10.1099/mic.0.000222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais T. R. T., Keller N. P. (2009). Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22 447–465. 10.1128/CMR.00055-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinamarco T., Brown N. A., Almeida R. S. C., Castro P. A., Savoldi M., Goldman M. H. S., et al. (2012). Aspergillus fumigatus calcineurin interacts with a nucleoside diphosphate kinase. Microbes Infect. 14 922–929. 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova N., Khaldi N., Joardar V., Maiti R., Amedeo P., Anderson M., et al. (2008). Genomic islands in the pathogenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000046. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastebois A., Fontaine T., Latgé J. P., Mouyna I. (2010). β(1-3)glucanosyltransferase Gel4p is essential for Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 9 1294–1298. 10.1128/ec.00107-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann U., Qazi K. R., Johansson C., Hultenby K., Karlsson M., Lundeberg L., et al. (2011). Nanovesicles from Malassezia sympodialis and host exosomes induce cytokine responses – novel mechanisms for host-microbe interactions in atopic eczema. PLoS One 6:e21480. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Bona A., Llama-Palacios A., Parra C. M., Vivanco F., Nombela C., Monteoliva L., et al. (2015). Proteomics unravels extracellular vesicles as carriers of classical cytoplasmic proteins in Candida albicans. J. Proteome Res. 14 142–153. 10.1021/pr5007944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung M., Moon D. C., Choi C. W., Lee J. H., Bae Y. C., Kim J., et al. (2011). Staphylococcus aureus produces membrane-derived vesicles that induce host cell death. PLoS One 6:e27958. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillmann F., Heinekamp T., Brakhage A. A., Bzymek K. P., Straßburger M., Bagramyan K., et al. (2016). The crystal structure of peroxiredoxin Asp f3 provides mechanistic insight into oxidative stress resistance and virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus. Sci. Rep. 6:33396. 10.1038/srep33396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdom M. D., Lechenne B., Hay R. J., Hamilton A. J., Monod M. (2000). Production and characterization of recombinant Aspergillus fumigatus Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase and its recognition by immune human sera. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38 558–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M. A. K., De Almeida J. R. F., Jannuzzi G. P., Cronemberger-Andrade A., Torrecilhas A. C. T., Moretti N. S., et al. (2018). Extracellular vesicles from Sporothrix brasiliensis are an important virulence factor that induce an increase in fungal burden in experimental sporotrichosis. Front. Microbiol. 9:2286. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe L. S., Nimrichter L., Rodrigues M. L., Del Poeta M. (2016). Potential roles of fungal extracellular vesicles during infection. mSphere 1:e00099-16. 10.1128/mSphere.00099-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn M. J., Kesty N. C. (2005). Bacterial outer membrane vesicles and the host-pathogen interaction. Genes Dev. 19 2645–2655. 10.1101/gad.1299905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers M. E., Hokke C. H., Smits H. H., Nolte-’t Hoen E. N. M. (2018). Pathogen-derived extracellular vesicle-associated molecules that affect the host immune system: an overview. Front. Microbiol. 9:2182. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurup V. P., Banerjee B., Hemmann S., Greenberger P. A., Blaser K., Crameri R. (2000). Selected recombinant Aspergillus fumigatus allergens bind specifically to IgE in ABPA. Clin. Exp. Allergy 30 988–993. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacadena J., Álvarez-García E., Carreras-Sangrà N., Herrero-Galán E., Alegre-Cebollada J., García-Ortega L., et al. (2007). Fungal ribotoxins: molecular dissection of a family of natural killers. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 31 212–237. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00063.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambou K., Lamarre C., Beau R., Dufour N., Latge J. P. (2010). Functional analysis of the superoxide dismutase family in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol. Microbiol. 75 910–923. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07024.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latgé J. P. (1999). Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12 310–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Momany C., Momany M. (2003). SwoHp, a nucleoside diphosphate kinase, is essential in. Society 2 1169–1177. 10.1128/EC.2.6.1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler J., Haddad Z., Bonin M., Romeike N., Mezger M., Schumacher U., et al. (2009). Interaction analyses of human monocytes co-cultured with different forms of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Med. Microbiol. 58 49–58. 10.1099/jmm.0.003293-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrad B., Strieter R. M., Standiford T. J. (1999). Role of TNF-{alpha} in pulmonary host defense in murine invasive aspergillosis. J. Immunol. 162 1633–1640. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meletiadis J., Meis J. F. G. M., Mouton J. W., Verweij P. E. (2001). Analysis of growth characteristics of filamentous fungi in different nutrient media. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39 478–484. 10.1128/jcm.39.2.478-484.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momany M., Westfall P. J., Abramowsky G. (1999). Aspergillus nidulans swo mutants show defects in polarity establishment, polarity maintenance and hyphal morphogenesis. Genetics 151 557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller W. A. (2013). Getting leukocytes to the site of inflammation. Vet. Pathol. 50 7–22. 10.1177/0300985812469883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola A. M., Frases S., Casadevall A. (2009). Lipophilic dye staining of Cryptococcus neoformans extracellular vesicles and capsule. Eukaryot. Cell 8 1373–1380. 10.1128/EC.00044-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen-Hamilton M., Hamilton R. T. (1982). Secreted proteins, intercellular communication, and the mitogenic response. Cell Biol. Int. Rep. 6 815–836. 10.1016/0309-1651(82)90142-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira D. L., Freire-de-Lima C. G., Nosanchuk J. D., Casadevall A., Rodrigues M. L., Nimrichter L. (2010). Extracellular vesicles from Cryptococcus neoformans modulate macrophage functions. Infect. Immun. 78 1601–1609. 10.1128/IAI.01171-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmo N., Turnay J., de Buitrago G. G., de Silanes I. L., Gavilanes J. G., Lizarbe M. A. (2001). Cytotoxic mechanism of the ribotoxin α-sarcin. Eur. J. Biochem. 268 2113–2123. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara T. R., Cowen L. E. (2014). Hsp90-dependent regulatory circuitry controlling temperature-dependent fungal development and virulence. Cell. Microbiol. 16 473–481. 10.1111/cmi.12266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara T. R., Robbins N., Cowen L. E. (2017). The Hsp90 chaperone network modulates Candida virulence traits. Trends Microbiol. 25 809–819. 10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prados-Rosales R., Baena A., Martinez L. R., Luque-Garcia J., Kalscheuer R., Veeraraghavan U., et al. (2011). Mycobacteria release active membrane vesicles that modulate immune responses in a TLR2-dependent manner in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121 1471–1483. 10.1172/JCI44261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran H., Jayaraman V., Banerjee B., Greenberger P. A., Kelly K. J., Fink J. N., et al. (2002). IgE binding conformational epitopes of Asp f 3, a major allergen of Aspergillus fumigatus. Clin. Immunol. 103 324–333. 10.1006/clim.2002.5219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves E. P., Messina C. G. M., Doyle S., Kavanagh K. (2004). Correlation between gliotoxin production and virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus in Galleria mellonella. Mycopathologia 158 73–79. 10.1023/B:MYCO.0000038434.55764.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M. L., Nakayasu E. S., Oliveira D. L., Nimrichter L., Nosanchuk J. D., Almeida I. C., et al. (2008). Extracellular vesicles produced by Cryptococcus neoformans contain protein components associated with virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 7 58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M. L., Nimrichter L., Oliveira D. L., Frases S., Miranda K., Zaragoza O., et al. (2007). Vesicular polysaccharide export in Cryptococcus neoformans is a eukaryotic solution to the problem of fungal trans-cell wall transport. Eukaryot. Cell 6 48–59. 10.1128/ec.00318-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupert D. L. M., Claudio V., Lässer C., Bally M. (2017). Methods for the physical characterization and quantification of extracellular vesicles in biological samples. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1861 3164–3179. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorey J. S., Cheng Y., Singh P. P., Smith V. L. (2015). Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO Rep. 16 24–43. 10.15252/embr.201439363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. N., Li F. Q., Huang M., Lu J. F., Kong X. X., Wang S. Q., et al. (2012). Immunoproteomics based identification of thioredoxin reductase GliT and novel Aspergillus fumigatus antigens for serologic diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. BMC Microbiol. 12:11. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva B. M. A., Prados-Rosales R., Espadas-Moreno J., Wolf J. M., Luque-Garcia J. L., Gonçalves T., et al. (2014). Characterization of Alternaria infectoria extracellular vesicles. Med. Mycol. 52 202–210. 10.1093/mmy/myt003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva R. P., Puccia R., Rodrigues M. L., Oliveira D. L., Joffe L. S., César G. V., et al. (2015). Extracellular vesicle-mediated export of fungal RNA. Sci. Rep. 5:7763. 10.1038/srep07763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriani F. M., Malavazi I., Ferreira M. E., Savoldi M., Kress M. R., Goldman M. H. S., et al. (2008). Functional characterization of the Aspergillus fumigatus CRZ1 homologue, CrzA. Mol. Microbiol. 67 1274–1291. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S., Thakur R., Shankar J. (2015). Role of heat-shock proteins in cellular function and in the biology of fungi. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2015:132635. 10.1155/2015/132635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunawaki S., Yoshida L. S., Nishida S., Kobayashi T., Shimoyama T. (2004). Fungal metabolite gliotoxin inhibits assembly of the human respiratory burst NADPH oxidase. Infect. Immun. 72 3373–3382. 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3373-3382.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyanova S., Temu T., Cox J. (2016). The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat. Protoc. 11 2301–2319. 10.1038/nprot.2016.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo M. C., Matsuo A. L., Ganiko L., Medeiros L. C. S., Miranda K., Silva L. S., et al. (2011). The pathogenic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis exports extracellular vesicles containing highly Immunogenic α-galactosyl epitopes. Eukaryot. Cell 10 343–351. 10.1128/EC.00227-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas G., Rocha J. D. B., Oliveira D. L., Albuquerque P. C., Frases S., Santos S. S., et al. (2015). Compositional and immunobiological analyses of extracellular vesicles released by Candida albicans. Cell. Microbiol. 17 389–407. 10.1111/cmi.12374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yáñez-Mó M., Siljander P. R.-M., Andreu Z., Zavec A. B., Borra F. E., Buzas E. I., et al. (2015). Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 14:27066. 10.3402/jev.v4.27066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y. J., Kim O. Y., Gho Y. S. (2014). Extracellular vesicles as emerging intercellular communicasomes. BMB Rep. 47 531–539. 10.5483/BMBRep.2014.47.10.164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y., Ogura Y., Hasunuma K. (2006). Interaction of nucleoside diphosphate kinase and catalases for stress and light responses in Neurospora crassa. FEBS Lett. 580 3282–3286. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarnowski R., Sanchez H., Covelli A. S., Dominguez E., Jaromin A., Bernhardt J., et al. (2018). Candida albicans biofilm-induced vesicles confer drug resistance through matrix biogenesis. PLoS Biol. 16:e2006872. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Lü Y., Ouyang H., Zhou H., Yan J., Du T., et al. (2013). N-Glycosylation of Gel1 or Gel2 is vital for cell wall β-glucan synthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. Glycobiology 23 955–968. 10.1093/glycob/cwt032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.