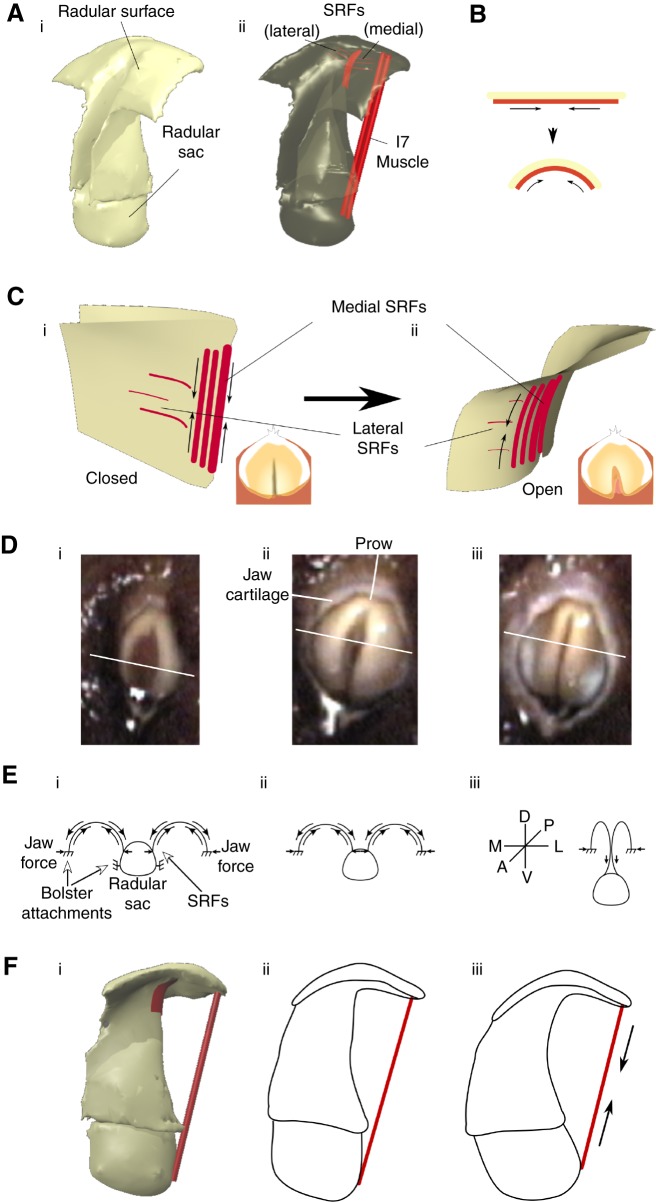

Fig. 7.

Biomechanics of the actions of the SRFs and the I7 muscles. (Ai) Three-dimensional view of radular surface, stalk and sac. (Aii) Location of SRFs and I7 muscles that contribute to opening are highlighted in red. (B) Schematic indicating compressive actions of SRFs that induce outward curvature of radular surface. (C) Stiff crease in radular surface induces SRFs (shown in Ci) to curve radular surface away from crease, causing opening (Cii). Insets show top view of radular surface. (Di) Video frame of early protraction of biting in an intact animal. (Dii) Video frame of peak protraction during the same bite; the opening of the radular halves and their gentle curvature is clearly visible. (Diii) Video frame at the onset of retraction during the same bite. The central stiff ridge is clearly visible. Schematics shown below the video frames (in E) are oriented such that the radular surface is dorsal, the radular sac is ventral, the prow is posterior and the radular cleft is anterior. White lines across the surface of the radula in each video frame (D) indicate the ‘cross-section’ represented by the schematic drawing. Solid arrows represent forces. (Ei) Early protraction. (Eii) Peak protraction. (Eiii) Onset of retraction and ridge formation. See Results, ‘A biomechanical hypothesis for the actions of the SRFs’. (Fi) The location of I7 muscles relative to the radular surface and the radular sac. As the I7 muscles contract (Fii), they pull the radular surface apart and also induce the radular stalk to move towards the radular surface (Fiii).