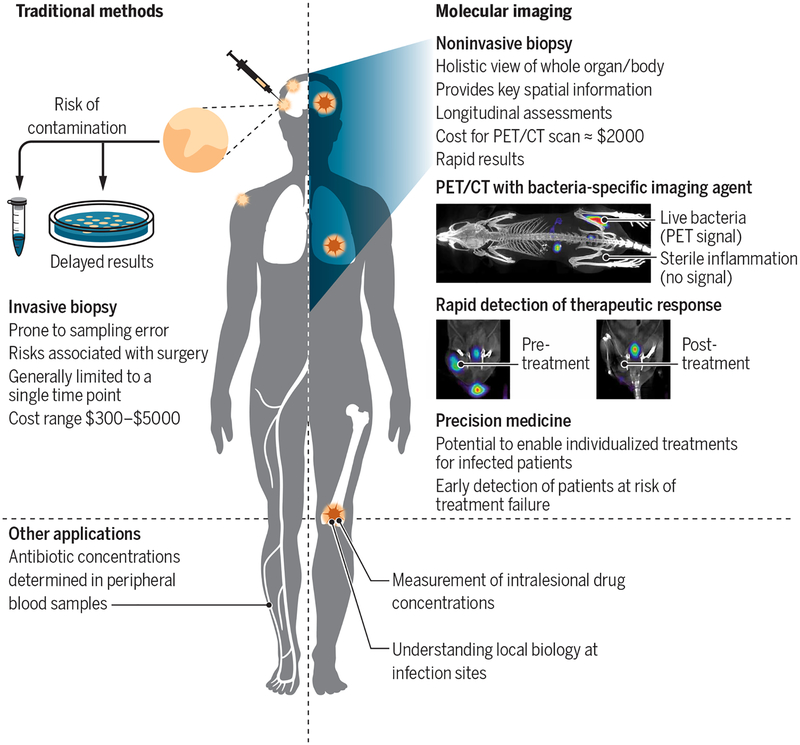

Fig. 2. Comparison of traditional methods with molecular imaging.

Traditional diagnostic tools for infectious diseases depend on available clinical samples (blood and urine), with most deep-seated infections requiring surgical biopsies to establish a definitive diagnosis. Microbiological or molecular assays are performed on surgical biopsies; however, some organisms are difficult to cultivate ex vivo or need a long time to grow, which can limit or delay the diagnosis. Clinically available imaging tests [radiographs, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] incorporated into the diagnostic workup are not specific for infection and reflect a combination of infection and the host inflammatory response. Molecular imaging can provide spatial and temporal information about infections and can monitor response to treatment. An example of positron emission tomography (PET)/CT imaging in mice using a bacteria-specific imaging agent, 2-18F-fluorodeoxysorbitol, is shown. The radiopharmaceutical accumulates in the infected muscle but not in the inflamed sterile muscle. Repeat imaging before and after antibiotic treatment can also provide rapid efficacy monitoring, demonstrating a PET signal proportionate to the bacterial burden. Adapted from Weinstein et al. (23).