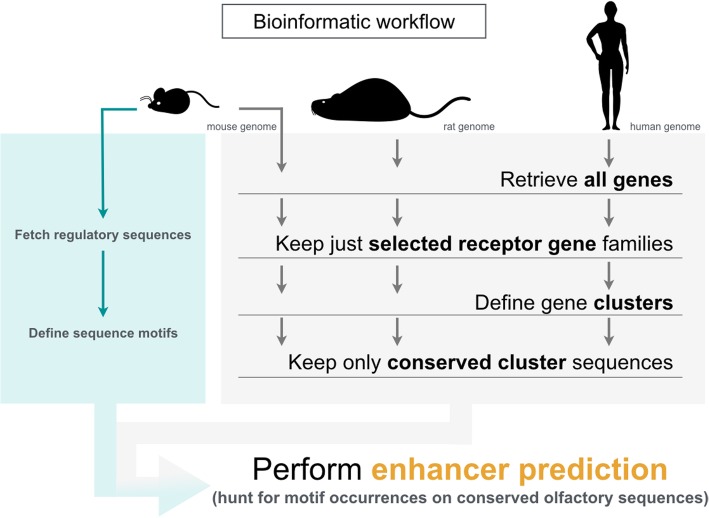

Fig. 1.

Outline of the bioinformatic framework. We retrieved gene information, including coordinates, for all genes annotated at Ensembl within the genomes of mouse (GRCm38), rat (Rnor_6.0) and human (GRCh38). From these, we considered most receptor genes responsible for the detection of odorants, i.e. odorant (OR), vomeronasal (VR), trace amine-associated (TAAR) and formyl peptide (FPR) receptor genes. For mouse only, T-cell receptor (TCR) genes were also kept. In every species, we combined gene families as such: OR and TAAR genes into a main olfactory epithelium (MOE) list; VR and FPR genes into a vomeronasal organ (VNO) list. MOE and VNO were also merged to form a list named olfactome. Members for each of the studied gene families are typically packed next to each other in a few chromosomal locations, forming clusters. We assessed number and identity of loci within each combined list (and for mouse TCR genes). Crucial for the definition of a locus is the adoption of a threshold (or cutoff) distance, above which two neighboring genes are considered as belonging to different chromosomal entities. Such value was varied between 0.1 Mb and the length of the widest chromosome found within its genome, each time yielding a specific locus composition. For selected cluster architectures, we fetched evolutionarily conserved sequences found within (or nearby) defined genomic locations; on these we predicted novel gene enhancers, based on sequence motifs mostly derived from known mouse OR promoters and regulatory elements