Abstract

The reversible capture of water vapor at low humidity can enable transformative applications such as atmospheric water harvesting and heat transfer that uses water as a refrigerant, replacing environmentally detrimental hydro- and chloro-fluorocarbons. The driving force for these applications is governed by the relative humidity at which the pores of a porous material fill with water. Here, we demonstrate modulation of the onset of pore-filling in a family of metal–organic frameworks with record water sorption capacities by employing anion exchange. Unexpectedly, the replacement of the structural bridging Cl– with the more hydrophilic anions F– and OH– does not induce pore-filling at lower relative humidity, whereas the introduction of the larger Br– results in a substantial shift toward lower relative humidity. We rationalize these results in terms of pore size modifications as well as the water hydrogen bonding structure based on detailed infrared spectroscopic measurements. Fundamentally, our data suggest that, in the presence of strong nucleation sites, the thermodynamic favorability of water pore-filling depends more strongly on the pore diameter and the interface between water in the center of the pore and water bound to the pore walls than the hydrophilicity of the pore wall itself. On the basis of these results, we report two materials that exhibit record water uptake capacities in their respective humidity regions and extended stability over 400 water adsorption–desorption cycles.

Introduction

The capture of water vapor at low relative humidity (0–40% RH) can be used to drive heat transfer,1−8 to trap atmospheric water vapor,2,9−13 or for dehumidification.14−18 Recent advancements in the design of porous materials for these applications have moved next-generation water sorbents closer to applicability,2,4,13,15,16 but methods to precisely control the hydrophilicity of a sorbent are still needed. Complicating sorbent design, the mechanism of water uptake at low relative humidity remains incompletely understood due to the complex nature of the water phase-change process as well as the difficulty of accurately simulating the properties of water.19,20

In order to achieve maximum thermal efficiency, a porous material should have a high capacity for water and should adsorb water reversibly and in a stepwise fashion at a precise RH.21 Additionally, although nontrivial, it is highly desirable to have synthetic control over the position (% RH) of the water uptake step.22−24 The % RH whereupon a pore fills with water determines the driving force for heat transfer and, concomitantly, the temperature required to release water from the sorbent: more hydrophilic sorbents are capable of creating greater temperature gradients but also require more energy to cycle back to the dry state.21 In the case of atmospheric water capture, the % RH of the uptake step determines the applicable climatic region.11,13

Outside the confines of a porous material, water condensation occurs at 100% RH. In porous materials, water begins to occupy the voids at lower RH with decreasing pore diameter,25 and complete saturation occurs near 0% RH in some cases.1,26,27 Additionally, the hydrophilicity of the pore interior, modifiable via ligand functionalization,23,24,28 cation exchange,22 as well as exchange of supporting ligands,29 plays a role in determining the RH at which the pore will fill. These empirical design rules have guided the development of sorbents with impressive performance, even though the underlying hydrogen bonding structure of water in confined pores, which undoubtedly influences the position of the pore filling step, remains unclear. Indeed, water in confinement and along interfaces can have properties very different from that of bulk water, as the pore structure or interface itself impose restrictions on the complex hydrogen bonding structures.30,31 Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) provide an ideal platform for interrogating the hydrogen bonding structure of confined water because their modular nature allows for tuning of the pore size, metal ion, and hydrophilicity without altering the overall framework topology.32 In addition to precisely controlling the water uptake step position, the stability of water sorbents is also of paramount importance because applications for water harvesting or heat transfer will require active materials capable of undergoing thousands of adsorption cycles. This is an important practical consideration that only rarely is addressed in the academic literature.33

Recently, we reported a MOF that captures record quantities of water in the humidity region relevant for many applications.2 The water uptake capacity in this material is optimized: because the pore size is at the “critical diameter”25,34 for water capillary condensation during pore-filling, its high water capacity is completely reversible, without appreciable hysteresis. This minimizes the energy input required for cycling between the hydrated and dry states. The champion material, synthesized from the ligand bis(1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b],[4′,5′-i])dibenzo[1,4]dioxin (H2BTDD) and CoCl2·6H2O, exhibits a capacity of nearly 1 g of H2O g–1 of MOF.2 Here we report that the Ni2+ variant, Ni2Cl2BTDD, can be synthesized with greater crystallinity and porosity than previously possible, enabling it to match the capacity of the Co2+ material. We further show through extended cycling experiments that the decreased lability of Ni2+ 35 leads to excellent long-term stability well beyond that of the Co2+ analogue. Finally, we demonstrate that Ni2Cl2BTDD undergoes facile anion exchange whereby hydroxide, fluoride, or bromide anions isostructurally replace native chloride ligands (Figure 1). These anion metathesis manipulations modulate hydrogen bonding interactions between water and the pore wall, resulting in stark differences in water uptake at low RH for the different anion-containing MOFs. Fundamentally, these structural perturbations provide a platform to investigate the hydrogen-bonding structure of confined and interfacial water during the pore-filling process by diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS). Beyond tuning the hydrophilicity, the series of halogens modulates the pore size of the respective MOFs in a nonintuitive way, with the larger bromide yielding the shortest a and b cell parameters. This subtle variation leads to critical changes in the hydrogen bonding structure of water within the pore. Consequently, pore filling occurs at substantially lower relative humidity (RH) in Ni2Br2BTDD. This is counterintuitive because below 5% RH the bromide derivative is the least hydrophilic. Importantly, the introduction of bromide maintains exceptional water stability, with negligible loss of capacity after 400 adsorption cycles. These systematic synthetic variations further our fundamental understanding of water in confinement and provide a promising new adsorbent with record water capacity at low (<25%) RH and excellent long-term stability.

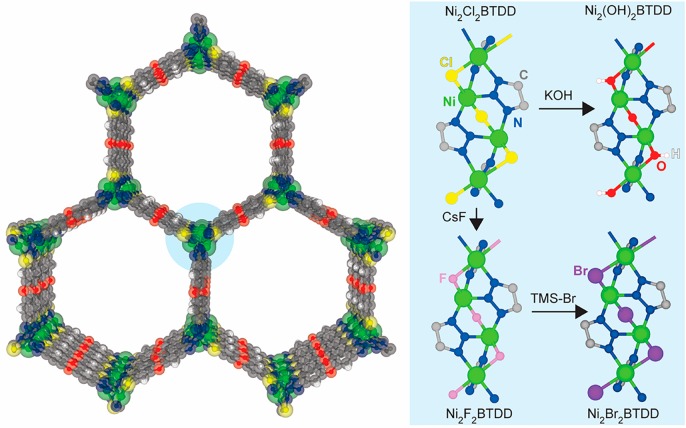

Figure 1.

Structure of Ni2X2BTDD (X = Cl, F, Br, OH). Left: View parallel to the c axis. Right: View of anion-exchanged SBUs perpendicular to the c axis and synthetic pathways.

Results and Discussion

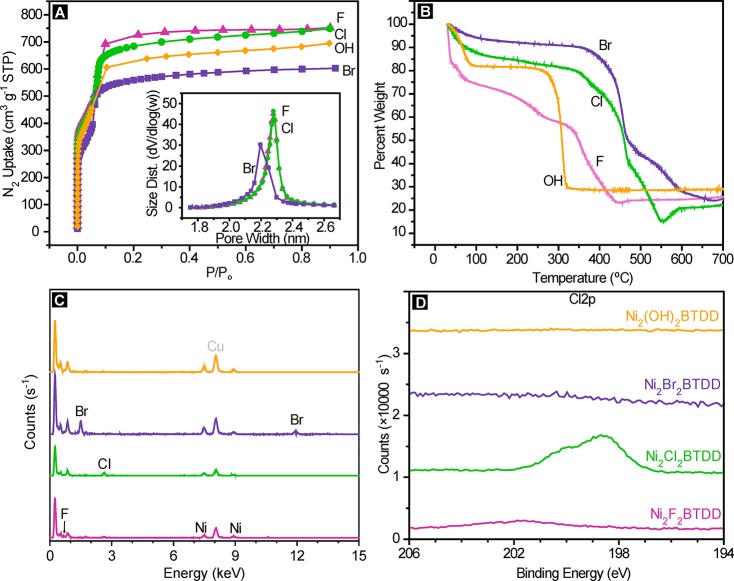

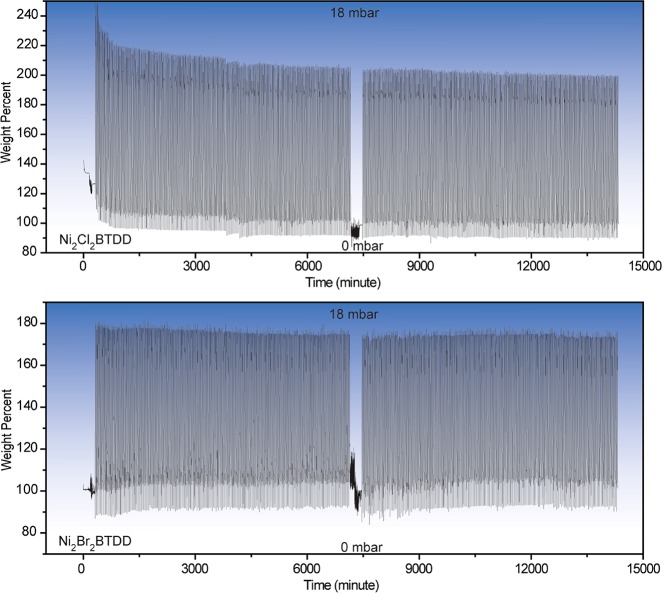

Highly crystalline Ni2Cl2BTDD can be accessed from H2BTDD and NiCl2·6H2O under solvothermal conditions in a mixture of 100:100:64 DMF:MeOH:HClaq at 100 °C. A significantly greater acid concentration and higher temperatures than those used for isostructural materials with other metal cations such as Co2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, or Cu2+ allow for increased crystallinity with the more inert Ni2+. By powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) as well as a Brunauer–Emmet–Teller (BET) surface area analysis from a nitrogen isotherm at 77 K, the new synthesis of Ni2Cl2BTDD results in improvements in crystallinity as well as porosity over previous reports of this material, with the improved MOF exhibiting a BET area of 1837 m2 g–1, in line with those of the previously reported Co, Mn, and Cu analogues (Figure 2A).36 Rietveld refinement of high-resolution synchrotron PXRD data provides the first experimental crystal structure of this material, confirming a hexagonal space group with unit cell parameters a = b = 38.5282(5) Å, c = 8.1888(1) Å (Figure S9.1). Accompanying the increased BET surface area is a significantly larger water uptake capacity at 25 °C of 1.07 g g–1 (Figure 3), an over 40% improvement over the value reported previously for this material.2 This capacity is the highest reported for materials with α (defined as the % RH at which half of the total uptake is reached) below 35% RH. Importantly, Ni2Cl2BTDD adsorbs water reversibly, that is, without hysteresis. As expected due to the greater inertness of Ni2+ relative to Co2+,35 extended pressure-swing cycling revealed remarkable stability for Ni2Cl2BTDD, which maintains 98% of its original water uptake capacity by weight (wt %) after 400 cycles (Figure 4A), with negligible changes in crystallinity or N2 uptake after water cycling (Figures S3.1 and S4.1). In contrast, the uptake capacity of Co2Cl2BTDD decays by 6.3% over 30 cycles, with no clear plateau in the decay rate.2 These data further reinforce the concept of using inert metal ions to enhance framework chemical stability.37

Figure 2.

(A) Nitrogen isotherms at 77 K for Ni2X2BTDD. Inset: Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH)39 pore size distribution calculated using the Kruk–Jaroniec–Sayari40 correction for hexagonal pores from the 77 K N2 adsorption isotherms. (B) Thermogravimetric analysis of Ni2X2BTDD. (C) Energy-dispersive X-ray spectra (EDS) for Ni2X2BTDD. (D) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) at the Cl 2p energy for Ni2X2BTDD.

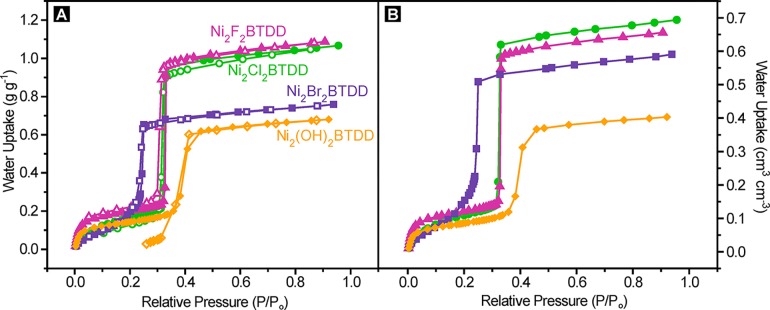

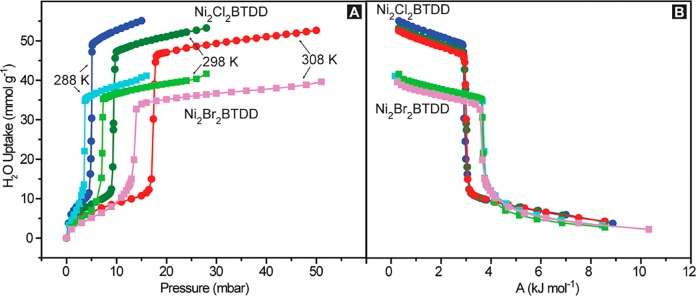

Figure 3.

(A) Water vapor adsorption (closed symbols) and desorption (open symbols) isotherms of Ni2Br2BTDD, Ni2Cl2BTDD, Ni2F0.83Cl0.17BTDD, and Ni2(OH)2BTDD measured at 25 °C. (B) Adsorption isotherms converted to volumetric units using the material density.

Figure 4.

400 cycles of water uptake for Ni2Cl2BTDD (top) and Ni2Br2BTDD (bottom), switching from 0 mbar of H2O to 18 mbar of H2O approximately every 15 min, with a variable phase delay period to switch between pressures. After 200 cycles, each sample was reactivated at 70 °C for 3 h.

Anion-Exchanged Variants of Ni2Cl2BTDD

Inspired by a recent report of anion exchange to replace the original Cl– by OH– in structurally related materials,38 we reasoned that the introduction of bridging anions such as OH– and F–, which could provide hydrogen bonding interactions for water, should create a more hydrophilic pore environment that would induce pore filling at lower RH. Soaking Ni2Cl2BTDD in a dilute aqueous solution of KOH yielded a crystalline material with undetectable chloride according to energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Figure 2C and D). Infrared spectroscopy (IR) of the hydroxide-exchanged material, Ni2(OH)2BTDD, kept under N2 upon activation revealed a hydroxide O–H stretching band at 3645 cm–1 (Figure 5A). The BET surface area of 1792 m2 g–1 is within 3% of that of Ni2Cl2BTDD, although Ni2(OH)2BTDD exhibits drastic mass loss in the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) near 250 °C as compared to 350 °C for the parent chloride material (Figure 2A and B).

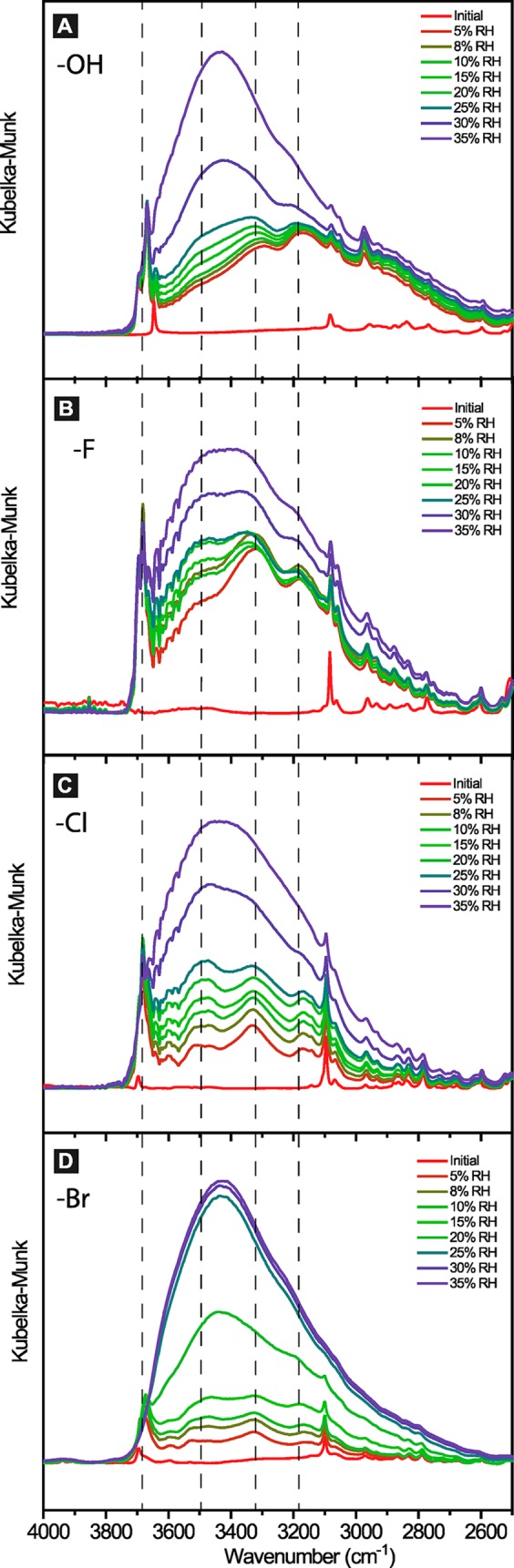

Figure 5.

Diffuse reflectance infrared spectroscopy (DRIFTS) focusing on the water O–H stretching region for Ni2(OH)2BTDD (A), Ni2F0.83Cl0.17BTDD (B), Ni2Cl2BTDD (C), and Ni2Br2BTDD (D) as a function of relative humidity (% RH). Full IR spectra are in Figures S6.1–S6.4. Dashed lines are guides for the eye for the peak maxima of four major regions of the OH stretch.

As expected, a water isotherm for Ni2(OH)2BTDD reveals greater initial hydrophilicity, with increased water uptake before 5% RH. However, after 5% RH, the hydroxide material exhibits a decreased water capacity compared with the chloride analogue. Moreover, the OH– material has a greatly reduced uptake step in the pore-filling region (Figures 3 and S10.1) and exhibits an irreversible desorption isotherm, along with a steep decline in capacity upon cycling beyond the initial cycle (Figure S7.1). Although PXRD demonstrated that at least some of the sample maintains crystallinity (Figure S3.2) upon water exposure, a N2 isotherm revealed significantly reduced pore volume and a decreased BET area of 980 m2 g–1 for Ni2(OH)2BTDD (Figure S4.2).

An alternative path toward increasing framework-water hydrogen bonding is the exchange of Cl– by F–. Because of its reduced basicity compared to OH–, F– may disfavor proton transfer from guest water molecules, which in the case of Ni2(OH)2BTDD may lead to its ultimate collapse. Soaking as-synthesized Ni2Cl2BTDD in a DMF solution of excess CsF for 12 h results in nearly quantitative exchange of Cl– for F–, as verified by EDS and XPS analyses (Figures 2C,D, S5.1, and S5.2). The precise F:Cl ratio was determined by treating the fluoride-exchanged sample with trimethylsilyl bromide (TMS-Br), which produces quantitatively the bromide-exchanged MOF, Ni2Br2BTDD, and soluble trimethylsilyl-fluoride (TMS-F) and trimethylsilyl-chloride (TMS-Cl). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis of the filtrate revealed a TMS-F:TMS-Cl ratio of 1.0:0.2 and thus the formula Ni2F0.83Cl0.17BTDD for the fluoride-exchanged MOF (Figure S8.1). After restraining the F:Cl ratio to within 2% of the NMR-determined value, Rietveld refinement of high-resolution synchrotron PXRD data also converged to 19% chloride and 81% fluoride occupancy for the fluoride-exchanged MOF (Figure S9.2). The BET surface area, as measured by a 77 K N2 isotherm, is 1770 m2 g–1, which is essentially identical to that of the hydroxide analogue (Figure 2A), whereas TGA indicates substantial mass loss around 200 °C (Figure 2B).

Ni2F0.83Cl0.17BTDD indeed adsorbs substantially more water than Ni2Cl2BTDD at low RH, below the pore-filling pressure. In particular, even at 2% RH, Ni2F0.83Cl0.17BTDD captures 1.3 molecules of water per Ni2+ open coordination site, whereas Ni2Cl2BTDD captures only 0.6 H2O per Ni2+ under the same conditions (Figure S10.1). We expected that this increased water uptake at low RH would induce the pore-filling step to occur at a lower vapor pressure. Interestingly, this is not the case, and pore-filling step occurs at almost exactly the same relative humidity, 32% RH, in the fluoride-exchanged material as in the parent chloride analogue (Figure 3). Less encouragingly, even though Ni2F0.83Cl0.17BTDD largely retains its porosity (Figure S4.3), PXRD reveals the emergence of a broad new peak around 2θ = 7°, indicating partial amorphization (Figure S3.4), and a water cycling experiment indicates rapid decline in capacity after the initial cycle (Figure S7.2).

Close inspection of the structural parameters of the anion-exchanged MOFs revealed a surprise expansion of the a, b parameters from 38.5282(5) Å for Ni2Cl2BTDD to 38.6092(5) Å upon fluoride exchange, despite the expected contraction of the c parameter upon replacing the larger Cl– with F– (Table 1). Computational optimization of the two idealized, fully exchanged fluoride and chloride structures by density functional theory (DFT) confirmed this unexpected trend and further predicted that the bromide-exchanged analogue, Ni2Br2BTDD, should have an even narrower pore due to a further reduction of a and b by at least 0.1 Å relative to Ni2Cl2BTDD (Table 1). Furthermore, owing to its larger covalent radius, Br– should protrude into the pore to a greater extent than any of the other anions, further narrowing the pore diameter and potentially leading to water uptake at lower RH due to increased confinement.

Table 1. Unit Cell and Select Crystallographic Parameters Determined by Rietveld Refinement or by DFTa.

| Rietveld | a, b | c | Ni–N1 | Ni–X | Ni–X–Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni2F0.83Cl0.17BTDD | 38.6092(5) | 8.0929(1) | 2.02(2) | 2.06(2) | 112.2(2)° |

| Ni2Cl2BTDD | 38.5282(5) | 8.1888(1) | 2.04(2) | 2.384(3) | 92.4(2)° |

| Ni2Br2BTDD | 38.4250(2) | 8.2077(1) | 2.03(1) | 2.503(1) | 87.4(2)° |

| DFT | a, b | c | Ni–N1 | Ni–X | Ni–X–Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni2F2BTDD | 38.846 | 7.663 | 1.91 | 2.02 | 100.4° |

| Ni2Cl2BTDD | 38.507 | 7.932 | 1.92 | 2.33 | 87.9° |

| Ni2Br2BTDD | 38.364 | 8.009 | 1.92 | 2.46 | 83.8° |

| Ni2(OH)2BTDD | 38.897 | 7.807 | 1.92 | 1.99 | 104.0° |

Distances are in Å; N1 is the central triazolate nitrogen.

Although accessing Ni2Br2BTDD directly from Ni2Cl2BTDD proved challenging, treatment of the fluoride-exchanged material with a small excess of TMS-Br led to quantitative formation of Ni2Br2BTDD and complete loss of Cl– and F–. EDS and XPS analysis of this material revealed prominent Br signals and undetectable signals for other halogens (Figures 2C,D and S5.3). Rietveld refinement of a PXRD pattern of Ni2Br2BTDD (Figure S9.3) revealed the predicted contraction of the a, b parameters to 38.4250(2), in excellent agreement with the DFT calculations (Table 1). The BET surface area of the Br material is 1467 m2 g–1 (Figure 2A). A BET area of 1530 m2 g–1 is reasonable considering the 1.2 times greater molecular weight of the Br MOF versus the Cl material. Pore size distribution analysis of the N2 adsorption isotherm reveals a small but significant reduction of the accessible pore diameter in Ni2Br2BTDD, from 2.3 nm in the Cl and F materials to 2.2 nm in the Br material (Figure 2A). Indeed, relatively small variations in accessible pore diameters induce large shifts in the % RH where water sorption occurs: isostructural MOFs with a pore size of 1.3 nm exhibit a pore-filling step near 0% RH.1

Despite the seemingly small reduction in pore diameter, a water isotherm for Ni2Br2BTDD material indicates that the pore-filling step shifts substantially, from 32% RH at 25 °C for the Cl– and F– derivatives to 24% RH for the Br– analogue (Figure 3A). As a consequence, Ni2Br2BTDD adsorbs a record 64% water by weight below 25% RH, a humidity value that is within the relevant range for many applications in heat transfer and atmospheric water capture.21,41 Notably, the total volumetric water uptake at 95% RH for Ni2Br2BTDD (Figure 3B) is only 15% lower than that of the chloride parent material. In the very low humidity region (below 15% RH), where hydrogen bonding interactions with the framework are expected to dominate, the water uptake for Ni2Br2BTDD is expectedly lower than that for either the chloride or fluoride analogues, which presumably establish stronger hydrogen bonding interactions with the first water molecules entering the pores (Figure S10.1). Crucially, Ni2Br2BTDD maintains its porosity and crystallinity upon water cycling for at least 400 cycles (Figures 4, S3.4, and S4.4).

Infrared Spectroscopic Investigation of Hydrogen Bonding during Water Adsorption

DRIFTS under variable RH provided critical experimental evidence regarding the influence of various anions on the hydrogen bonding structure of water within each material (Figures 5 and S6.1–S6.4). Four distinct regions in the water O–H stretching regime are clearly defined in all four anion-exchanged MOFs. These four regions correspond to water molecules in differing donor–acceptor hydrogen bonding environments, which are not equivalent within the time scale of our measurement. The highest energy vibration, at 3690 cm–1, corresponds to a nearly “free” water molecule, that is, without hydrogen bonding interactions.42 This environment is assigned to water bound initially to the Ni2+ open coordination sites. The next two lower energy bands, near 3500 and 3300 cm–1, are commonly seen in IR spectra of liquid water as well as ice and are assigned to liquid-like water with one donor and one acceptor (“DA”, 3545 cm–1) and tetrahedral, ice-like water with two donors and two acceptors (“DDAA”, 3275 cm–1), respectively. Liquid water contains these two components at roughly a 4:3 ratio at 25 °C.43,44 The band at 3120 is also more commonly associated with ice and is a convolution of water with one H atom donor and two O atom acceptors as well as the coupling between the O–H stretch fundamental and the HOH bend overtone.45

Ni2(OH)2BTDD exhibits a very broad O–H stretching region, which expands at low frequency down to 2600 cm–1 (Figure 5A). Such broad bands are commonly associated with charge transfer,46,47 presumably occurring in this case as proton transfer from adsorbed water to bridging hydroxide, to form a bridging water and a free hydroxide in the pore. We postulate that this charge transfer mechanism revealed by IR spectroscopy allows for ligand exchange and that this lability at the bridging positions results in pore collapse with the hydroxide-exchanged MOF.

In comparison with the chloride and bromide analogues, the fluoride-exchanged material exhibits a much greater signal intensity in the ice-like “DDAA” frequency region, particularly at low RH. For instance, at 5% RH, the region at 3275 cm–1 is much greater in intensity than the feature at 3545 cm–1 (Figure 5B). As RH increases to 8%, the “DDAA” region grows further, but ramping up the RH to 30% causes this region to decline in intensity, with concomitant emergence of the liquid-like “DA” region, which steadily increases until it is approximately equal in intensity with the “DDAA” region at 30% RH. The overall intensity of the whole O–H stretching region changes little from 5% RH to 30% RH, in agreement with the plateau in water uptake observed in this RH range in the water adsorption isotherm (Figure 3). From this data, we conclude that the ice-like water present at low RH in the Ni2F0.83Cl0.17BTDD material does not promote further pore-filling. Whereas the ice-like water has a saturated tetrahedral network of H-bonding interactions, the liquid-like “DA” water has donor and acceptor sites available to interact with further water molecules. Water in this liquid-like environment, with sites available to H-bond with incoming water molecules, is not initially favored in the fluoride material and only grows in at higher RH.

In contrast to the fluoride-exchanged material, the liquid-like “DA” and the ice-like “DDAA” signals in Ni2Br2BTDD become approximately equal in intensity at much lower RH (∼15%), whereupon the pore begins to fill (Figure 5D). In comparison, Ni2Cl2BTDD requires ∼25% RH for the intensity of the liquid-like “DA” signal to exceed that of the ice-like “DDAA” water (Figure 5C). Put another way, the bromide MOF has the least rigid hydrogen bonding network at low relative humidity. The emerging fundamental insight is that, in order for the pore to fill with water, there must be a sufficient concentration of water molecules with unsaturated hydrogen bonding environments to attract more water. These data implicate the hydrogen-bonding interface between water initially adsorbed at strong binding sites and incoming water in the center of the pore as a determining factor in the thermodynamic favorability of pore-filling at a given RH. The importance of this interfacial water–central water interface versus the interface between the pore wall and the interfacial water was not previously understood and may be related to the reduction in pore diameter below the “critical diameter” prior to the pore-filling step by preadsorbed water, which makes the water adsorption process in these materials reversible and without hysteresis.2

Potential Utility of Ni2Cl2BTDD and Ni2Br2BTDD in Applications Involving Water Sorption

Water cycling experiments for Ni2(OH)2BTDD and Ni2F0.83Cl0.17BTDD revealed steep declines in capacity with repeated cycling (Figures S7.1 and S7.2). In contrast, Ni2Br2BTDD appears to be essentially indefinitely stable, maintaining its crystallinity (Figure S3.5) and its initial water capacity of 65 wt % after 400 cycles (Figure 4), similar to the parent chloride material. The superlative stability of Ni2Cl2BTDD and Ni2Br2BTDD prompted us to further investigate these materials for applications in heat transfer. Variable temperature water isotherms (Figure 6A) were employed to confirm the applicability of a characteristic curve (Figure 6B), which converts the two independent variables governing uptake (temperature and pressure) into a single parameter, A, related to the Gibbs free energy.3,5,21 On the basis of the overlapping positions of the uptake step in the characteristic curve, this method can be used to calculate loadings at other temperatures and pressures relevant for heat transfer applications. Using the variable temperature water isotherms, the heat of adsorption for water in both chloride and bromide derivatives is approximately −57 kJ mol–1 at zero coverage (Figure S10.2). On the basis of the characteristic curve, for applications in heat transfer, the Cl– material can achieve a 19 °C temperature lift (the temperature difference between the environment and the output of a heat pump), with a requirement for thermal regeneration at approximately 53 °C. In contrast, the Br– material can achieve a 24 °C temperature lift and requires heating to 58 °C for regeneration. To our knowledge, each of these materials exhibits a record water capacity, measured either volumetrically or gravimetrically, compared to sorbents capable of equivalent respective temperature lifts (Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 6.

(A) Variable temperature water isotherms, obtained via the gravimetric method, for Ni2Cl2BTDD (blue 288 K, green 298 K, red 308 K) and Ni2Br2BTDD (light blue 288 K, light green 298 K, pink 308 K). (B) Characteristic curves for Ni2Cl2BTDD and Ni2Br2BTDD calculated from the water isotherms.

Table 2. Water Capacities for Selected Porous Materials with α at or below 25% RH.

| αa (% RH) | uptake (g g–1) | crystal ρ (g cm–3) | uptake (cm3 cm–3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQSOA Z0121 | 17 | 0.18 | 1.75 | 0.315 |

| AQSOA Z0521 | 25 | 0.18 | 1.75 | 0.315 |

| MIL-1605 | 8 | 0.37 | 1.15 | 0.426 |

| AQSOA Z0221 | 8 | 0.3 | 1.43 | 0.429 |

| CAU-1048 | 18 | 0.38 | 1.15 | 0.437 |

| Ni2Cl2BBTA1 | 3 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.44 |

| MOF-80110 | 9 | 0.28 | 1.59 | 0.445 |

| Ti-MIL-125-NH249 | 23 | 0.68 | 0.757 | 0.515 |

| MIP-2004 | 18 | 0.45 | 1.16 | 0.522 |

| MOF-84110 | 22 | 0.51 | 1.05 | 0.536 |

| ALPO-7850 | 18 | 0.32 | 1.7 | 0.544 |

| MOF-30313 | 15 | 0.48 | 1.159 | 0.556 |

| Ni2Br2BTDDb | 24 | 0.76 | 0.764 | 0.581 |

α is the % RH at which half of the total uptake at 95% RH is reached.

This work.

Table 3. Water Capacities for Selected Porous Materials with α at or below 35% RH.

| αa (% RH) | uptake (g g–1) | crystal ρ (g cm–3) | uptake (cm3 cm–3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UiO-6621 | 34 | 0.43 | 1.24 | 0.533 |

| Al fumarate21 | 28 | 0.45 | 1.24 | 0.558 |

| Co2Cl2BTDD2 | 29 | 0.97 | 0.65 | 0.631 |

| Ni2Cl2BTDDb | 32 | 1.07 | 0.64 | 0.685 |

α is the % RH at which half of the total uptake at 95% RH is reached.

This work.

Conclusions

Ni2Cl2BTDD is a strong candidate for water sorption applications, with a record reversible water uptake below 32% relative humidity. Because of the inertness of Ni2+, it exhibits exceptional stability toward water cycling, in excess of that previously reported for the analogous Co2+ material. Introduction of anions with greater potential for hydrogen bonding interactions, such as F– or OH–, did not lead to shifts in the water uptake step profile toward lower RH, though these anions did promote increased water adsorption at very low RH. These results indicate that, as long as nucleation sites exist for water, further increasing the pore wall hydrophilicity does not change the position of the water uptake step. Contraction of the accessible pore diameter by just 0.1 nm as well as modification of the polarity of initially adsorbed H2O by the introduction of Br– results in a pore-filling step at lower RH by 8%. The resulting Ni2Br2BTDD material has the greatest capacity, measured gravimetrically or volumetrically, of any material below 25% RH. The capacity of 0.64 g of water per g–1 of MOF achieved below 25% RH is a new record in this partial pressure region relevant for many applications in heat transfer and atmospheric water generation, which represents a large leap forward achieved via precise pore size control and polarity modification not possible in other materials.

Acknowledgments

Fundamental studies of small molecule interactions with MOFs are supported by the National Science Foundation through a CAREER Award to M.D. (DMR-1452612). A.J.R. is supported by the Martin Family Fellowship for Sustainability. Funding for water capture comes from the Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food Systems Lab (J-WAFS). Use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. This work made use of the Shared Experimental Facilities supported in part by the MRSEC Program of the National Science Foundation under award number DMR-1419807. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1548562. We thank Dr. Robert W. Day for assistance with acquiring XPS data.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b06246.

Experimental and computational procedures, synthetic methods, materials characterization, structural refinement information, and Figures S3.1–S10.2 (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): A.J.R. and M.D. are inventors on a patent pertaining to the materials discussed herein.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rieth A. J.; Wright A. M.; Rao S.; Kim H.; LaPotin A. D.; Wang E. N.; Dincă M. Tunable Metal–Organic Frameworks Enable High-Efficiency Cascaded Adsorption Heat Pumps. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (50), 17591–17596. 10.1021/jacs.8b09655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieth A. J.; Yang S.; Wang E. N.; Dincă M. Record Atmospheric Fresh Water Capture and Heat Transfer with a Material Operating at the Water Uptake Reversibility Limit. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3 (6), 668–672. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange M. F.; van Velzen B. L.; Ottevanger C. P.; Verouden K. J. F. M.; Lin L.-C.; Vlugt T. J. H.; Gascon J.; Kapteijn F. Metal–Organic Frameworks in Adsorption-Driven Heat Pumps: The Potential of Alcohols as Working Fluids. Langmuir 2015, 31 (46), 12783–12796. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Lee J. S.; Wahiduzzaman M.; Park J.; Muschi M.; Martineau-Corcos C.; Tissot A.; Cho K. H.; Marrot J.; Shepard W.; Maurin G.; Chang J.; Serre C. A Robust Large-Pore Zirconium Carboxylate Metal–Organic Framework for Energy-Efficient Water-Sorption-Driven Refrigeration. Nat. Energy 2018, 3 (11), 985–993. 10.1038/s41560-018-0261-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cadiau A.; Lee J. S.; Damasceno Borges D.; Fabry P.; Devic T.; Wharmby M. T.; Martineau C.; Foucher D.; Taulelle F.; Jun C. H.; Hwang Y. K.; Stock N.; De Lange M. F.; Kapteijn F.; Gascon J.; Maurin G.; Chang J. S.; Serre C. Design of Hydrophilic Metal Organic Framework Water Adsorbents for Heat Reallocation. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27 (32), 4775–4780. 10.1002/adma.201502418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khutia A.; Rammelberg H. U.; Schmidt T.; Henninger S.; Janiak C. Water Sorption Cycle Measurements on Functionalized MIL-101Cr for Heat Transformation Application. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25 (5), 790–798. 10.1021/cm304055k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeremias F.; Khutia A.; Henninger S. K.; Janiak C. MIL-100(Al, Fe) as Water Adsorbents for Heat Transformation Purposes—a Promising Application. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22 (20), 10148. 10.1039/C2JM15615F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer H.; Jeremias F.; Warlo A.; Füldner G.; Fröhlich D.; Janiak C.; Gläser R.; Henninger S. K. A Functional Full-Scale Heat Exchanger Coated with Aluminum Fumarate Metal–Organic Framework for Adsorption Heat Transformation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56 (29), 8393–8398. 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b00106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Yang S.; Rao S. R.; Narayanan S.; Kapustin E. A.; Furukawa H.; Umans A. S.; Yaghi O. M.; Wang E. N. Water Harvesting from Air with Metal-Organic Frameworks Powered by Natural Sunlight. Science 2017, 356 (6336), 430–434. 10.1126/science.aam8743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H.; Gándara F.; Zhang Y.-B.; Jiang J.; Queen W. L.; Hudson M. R.; Yaghi O. M. Water Adsorption in Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks and Related Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (11), 4369–4381. 10.1021/ja500330a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmutzki M. J.; Diercks C. S.; Yaghi O. M. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Water Harvesting from Air. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30 (37), 1704304. 10.1002/adma.201704304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Rao S. R.; Kapustin E. A.; Zhao L.; Yang S.; Yaghi O. M.; Wang E. N. Adsorption-Based Atmospheric Water Harvesting Device for Arid Climates. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 1191. 10.1038/s41467-018-03162-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathieh F.; Kalmutzki M. J.; Kapustin E. A.; Waller P. J.; Yang J.; Yaghi O. M. Practical Water Production from Desert Air. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4 (6), eaat3198. 10.1126/sciadv.aat3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui S.; Qin M.; Marandi A.; Steggles V.; Wang S.; Feng X.; Nouar F.; Serre C. Metal-Organic Frameworks as Advanced Moisture Sorbents for Energy-Efficient High Temperature Cooling. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8 (1), 15284. 10.1038/s41598-018-33704-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towsif Abtab S. M.; Alezi D.; Bhatt P. M.; Shkurenko A.; Belmabkhout Y.; Aggarwal H.; Weseliński Ł. J.; Alsadun N.; Samin U.; Hedhili M. N.; Eddaoudi M. Reticular Chemistry in Action: A Hydrolytically Stable MOF Capturing Twice Its Weight in Adsorbed Water. Chem. 2018, 4 (1), 94–105. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Li P.; Zhang X.; Li P.; Wasson M. C.; Islamoglu T.; Stoddart J. F.; Farha O. K. Reticular Access to Highly Porous Acs -MOFs with Rigid Trigonal Prismatic Linkers for Water Sorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (7), 2900–2905. 10.1021/jacs.8b13710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulhalim R. G.; Bhatt P. M.; Belmabkhout Y.; Shkurenko A.; Adil K.; Barbour L. J.; Eddaoudi M. A Fine-Tuned Metal-Organic Framework for Autonomous Indoor Moisture Control. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (31), 10715–10722. 10.1021/jacs.7b04132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo Y.-K.; Yoon J. W.; Lee J. S.; Hwang Y. K.; Jun C.-H.; Chang J.-S.; Wuttke S.; Bazin P.; Vimont A.; Daturi M.; Bourrelly S.; Llewellyn P. L.; Horcajada P.; Serre C.; Férey G. Energy-Efficient Dehumidification over Hierachically Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks as Advanced Water Adsorbents. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24 (6), 806–810. 10.1002/adma.201104084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceriotti M.; Fang W.; Kusalik P. G.; McKenzie R. H.; Michaelides A.; Morales M. A.; Markland T. E. Nuclear Quantum Effects in Water and Aqueous Systems: Experiment, Theory, and Current Challenges. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116 (13), 7529–7550. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros G. A.; Wikfeldt K. T.; Ojamäe L.; Lu J.; Xu Y.; Torabifard H.; Bartók A. P.; Csányi G.; Molinero V.; Paesani F. Modeling Molecular Interactions in Water: From Pairwise to Many-Body Potential Energy Functions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116 (13), 7501–7528. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lange M. F.; Verouden K. J. F. M.; Vlugt T. J. H.; Gascon J.; Kapteijn F. Adsorption-Driven Heat Pumps: The Potential of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115 (22), 12205–12250. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A. M.; Rieth A. J.; Yang S.; Wang E.; Dinca M. Precise Control of Pore Hydrophilicity Enabled by Post-Synthetic Cation Exchange in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3856. 10.1039/C8SC00112J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade C. R.; Corrales-Sanchez T.; Narayan T. C.; Dincă M. Postsynthetic Tuning of Hydrophilicity in Pyrazolate MOFs to Modulate Water Adsorption Properties. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6 (7), 2172. 10.1039/c3ee40876k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama G.; Matsuda R.; Sato H.; Hori A.; Takata M.; Kitagawa S. Effect of Functional Groups in MIL-101 on Water Sorption Behavior. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 157, 89–93. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canivet J.; Bonnefoy J.; Daniel C.; Legrand A.; Coasne B.; Farrusseng D. Structure–Property Relationships of Water Adsorption in Metal–Organic Frameworks. New J. Chem. 2014, 38 (7), 3102. 10.1039/C4NJ00076E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douss N.; Meunier F. Experimental Study of Cascading Adsorption Cycles. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1989, 44 (2), 225–235. 10.1016/0009-2509(89)85060-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Critoph R. E. Evaluation of Alternative Refrigerant-Adsorbent Pairs for Refrigeration Cycles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 1996, 16 (11), 891–900. 10.1016/1359-4311(96)00008-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padial N. M.; Quartapelle Procopio E.; Montoro C.; López E.; Oltra J. E.; Colombo V.; Maspero A.; Masciocchi N.; Galli S.; Senkovska I.; Kaskel S.; Barea E.; Navarro J. A. R. Highly Hydrophobic Isoreticular Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks for the Capture of Harmful Volatile Organic Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (32), 8290–8294. 10.1002/anie.201303484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Z.; He T.; Kong X. J.; Lv X. L.; Wu X. Q.; Li J. R. Tuning Water Sorption in Highly Stable Zr(IV)-Metal-Organic Frameworks through Local Functionalization of Metal Clusters. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (33), 27868–27874. 10.1021/acsami.8b09333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. G.; Gierszal K. P.; Wang P.; Ben-Amotz D. Water Structural Transformation at Molecular Hydrophobic Interfaces. Nature 2012, 491 (7425), 582–585. 10.1038/nature11570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga K.; Gao G. T.; Tanaka H.; Zeng X. C. Formation of Ordered Ice Nanotubes inside Carbon Nanotubes. Nature 2001, 412 (6849), 802–805. 10.1038/35090532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H.; Cordova K. E.; O’Keeffe M.; Yaghi O. M. The Chemistry and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 2013, 341 (6149), 1230444–1230444. 10.1126/science.1230444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPotin A.; Kim H.; Rao S. R.; Wang E. N. Adsorption-Based Atmospheric Water Harvesting: Impact of Material and Component Properties on System-Level Performance. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52 (6), 1588–1597. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coasne B.; Gubbins K. E.; Pellenq R. J. M. Temperature Effect on Adsorption/Desorption Isotherms for a Simple Fluid Confined within Various Nanopores. Adsorption 2005, 11, 289–294. 10.1007/s10450-005-5939-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen M. Fast Elementary Steps in Chemical Reaction Mechanisms. Pure Appl. Chem. 1963, 6, 97–115. 10.1351/pac196306010097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rieth A. J.; Tulchinsky Y.; Dincă M. High and Reversible Ammonia Uptake in Mesoporous Azolate Metal-Organic Frameworks with Open Mn, Co, and Ni Sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (30), 9401–9404. 10.1021/jacs.6b05723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieth A. J.; Dincă M. Controlled Gas Uptake in Metal-Organic Frameworks with Record Ammonia Sorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (9), 3461–3466. 10.1021/jacs.8b00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Huang N. Y.; Shen J. Q.; Liao P. Q.; Chen X. M.; Zhang J. P. Hydroxide Ligands Cooperate with Catalytic Centers in Metal-Organic Frameworks for Efficient Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (1), 38–41. 10.1021/jacs.7b10107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett E. P.; Joyner L. G.; Halenda P. P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73 (1), 373–380. 10.1021/ja01145a126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M.; Jaroniec M.; Sayari A. Application of Large Pore MCM-41 Molecular Sieves To Improve Pore Size Analysis Using Nitrogen Adsorption Measurements. Langmuir 1997, 13 (23), 6267–6273. 10.1021/la970776m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen D.; Bendix P.; Reinsch H.; Fröhlich D.; Kummer H.; Möllers M.; Hügenell P. P. C.; Gläser R.; Henninger S.; Stock N.; Kalmutzki M. J.; Diercks C. S.; Yaghi O. M. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Water Harvesting from Air. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30 (37), 1704304. 10.1002/adma.201704304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Bernardina S.; Paineau E.; Brubach J.-B.; Judeinstein P.; Rouzière S.; Launois P.; Roy P. Water in Carbon Nanotubes: The Peculiar Hydrogen Bond Network Revealed by Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (33), 10437–10443. 10.1021/jacs.6b02635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe C.; Lademann J.; Darvin M. E. Depth Profiles of Hydrogen Bound Water Molecule Types and Their Relation to Lipid and Protein Interaction in the Human Stratum Corneum: In Vivo. Analyst 2016, 141 (22), 6329–6337. 10.1039/C6AN01717G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byl O.; Liu J. C.; Wang Y.; Yim W. L.; Johnson J. K.; Yates J. T. Unusual Hydrogen Bonding in Water-Filled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (37), 12090–12097. 10.1021/ja057856u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter K. M.; Shakib F. A.; Paesani F. Disentangling Coupling Effects in the Infrared Spectra of Liquid Water. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122 (47), 10754–10761. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b09910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katada M.; Fujii A. Infrared Spectroscopy of Protonated Phenol-Water Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 5822–5831. 10.1021/acs.jpca.8b04446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges D. D.; Semino R.; Devautour-Vinot S.; Jobic H.; Paesani F.; Maurin G. Computational Exploration of the Water Concentration Dependence of the Proton Transport in the Porous UiO-66(Zr)-(CO2H)2 Metal-Organic Framework. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29 (4), 1569–1576. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b04257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich D.; Pantatosaki E.; Kolokathis P. D.; Markey K.; Reinsch H.; Baumgartner M.; Van Der Veen M. A.; De Vos D. E.; Stock N.; Papadopoulos G. K.; Henninger S. K.; Janiak C. Water Adsorption Behaviour of CAU-10-H: A Thorough Investigation of Its Structure-Property Relationships. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4 (30), 11859–11869. 10.1039/C6TA01757F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sohail M.; Yun Y. N.; Lee E.; Kim S. K.; Cho K.; Kim J. N.; Kim T. W.; Moon J. H.; Kim H. Synthesis of Highly Crystalline NH2-MIL-125 (Ti) with S-Shaped Water Isotherms for Adsorption Heat Transformation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17 (3), 1208–1213. 10.1021/acs.cgd.6b01597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuhas B. D.; Mowat J. P. S.; Miller M. A.; Sinkler W. AlPO-78: A 24-Layer ABC-6 Aluminophosphate Synthesized Using a Simple Structure-Directing Agent. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30 (3), 582–586. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b04891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.