Abstract

People with pituitary disease report impairments in quality of life. The aim of this study was to elucidate the impact of the pituitary condition on the lives of partners. Four focus groups of partners of people with pituitary disease (Cushing’s disease, non-functioning adenoma, acromegaly, prolactinoma) were conducted. Partners mentioned worries related to the pituitary disease and negative beliefs about medication, coping challenges, relationship issues, social issues and unmet needs regarding care. This study emphasizes the importance of not only paying attention to psychosocial well-being of people with pituitary disease but also to their partners.

Keywords: caregivers, coping strategies, hypopituitarism, partners, pituitary adenomas, quality of life

Introduction

Pituitary adenomas can be considered a rare disease with an estimated prevalence of 78–94 cases per 100,000 individuals and an incidence of four cases per 100,000 individuals (Karavitaki, 2012). These benign tumours on the pituitary gland can result in classical medical conditions, such as Cushing’s disease (CD), acromegaly (ACRO), prolactinoma (PRL) or clinically non-functioning pituitary adenoma (NFA). These conditions can be categorized by aetiology. For instance, CD is referred to an overproduction of cortisol and is related to hypertension, changes in physical appearance and proximal muscle weakness. ACRO is characterized by an overproduction of growth hormone and is related to physical disfigurement, mainly involving the face, hands and feet. PRL is featured by an overproduction of prolactin resulting in milk production by the breast and reduced libido in both men and women and menstrual problems in women. Although people with NFA are not exposed to hormone excess, they may suffer from the mass effects of the adenoma resulting in symptoms such as visual field defects and headaches. Pituitary adenomas can be treated by surgery and sometimes additional medical treatment or radiotherapy when needed. As a consequence of the mass effect of the adenoma and/or the treatment, the pituitary can be damaged resulting in hormonal insufficiency. When this is the case, people receive lifelong replacement therapy (Greenspan and Strewler, 1993). People with a pituitary adenoma report impairments in physical functioning, as well as in psychosocial functioning, which usually improve after biomedical treatment but which do not appear to normalize (Andela et al., 2015b). During the chronic state of their disease, people still report impairments in quality of life (QoL) (Biermasz et al., 2004; Dekkers et al., 2006; Kars et al., 2007; Van Aken et al., 2005). Considering these persistent impairments and the lifelong medical (replacement) therapy, pituitary disease can be considered a chronic condition. In a recent qualitative focus group study, these QoL impairments have been further elucidated in people with CD, ACRO, NFA and PRL (Andela et al., 2015a). They reported psychological complaints, problems with personality changes, issues regarding sexuality and a negative impact on the relationship with their partner.

Weitzner and Knutzen (1998) reviewed the literature on caregiving in dementia and cancer, and although the characteristics of these diseases are considerably different compared to pituitary disease, they suggested that there might be some issues that are also applicable to caregiving and family issues in pituitary disease. For instance, the authors reported that a major primary stressor in caregiving for people with dementia is the patients’ disruptive behavioural problems (e.g. personality changes, agitation) and suggested that this stressor has general applicability to caregiving for people with pituitary disease. Furthermore, the authors describe that when caregiving continues over a longer time period, changes in social support become more persistent and are less likely to return to the premorbid situation (Weitzner and Knutzen, 1998). To the best of our knowledge, there is one qualitative study in partners of people with pituitary disease, which partially confirmed the postulations of Weitzner and Knutzen. This qualitative study by Dunning and Alford (2009) explored experiences of partners of people with pituitary disease using a focus group and interviews (n = 12 partners). It was reported that the partner sometimes became annoyed by the tiredness and mood swings of the ill partner because there was no obvious cause. Some partners felt they had to take on extra responsibilities at home and managing the children. They were aware of the burden on their family, but they felt unable to cope emotionally or physically. However, in some cases the quality of the relationship was enhanced (Dunning and Alford, 2009).

From quantitative QoL studies in partners of people with other chronic diseases, it is known that partner QoL is negatively affected (Bergelt et al., 2008; Gottberg et al., 2014; McPherson et al., 2011; Parish and Lyng, 2003). From previous research, it is also known that the role of the partner also strongly influences QoL of people with chronic disease. For instance, unsupportive behaviour of partners was associated with more distress in women with early stage breast cancer (Manne et al., 2005). However, solicitous behaviour of partners of people with chronic fatigue syndrome negatively affected improvement in fatigue and disability during cognitive behavioural therapy (Verspaandonk et al., 2015).

People with a chronic disease, as well as their partners, develop representations of the disease, that is, illness perceptions. These illness perceptions can be categorized around five common themes: identity, cause, timeline, consequences and cure/control (Leventhal et al., 1980). Illness perceptions have been shown to exert a substantial influence on coping and QoL (Petrie and Weinman, 2006). In addition, addressing maladaptive illness perceptions has been shown to result in improvements in outcome measures (Jansen et al., 2011; Petrie et al., 2002). It is possible that illness perceptions of persons with a chronic disease differ from the ideas of their partners. For instance, partners of people with primary adrenal insufficiency, that is, Addison’s disease (AD), were more pessimistic about the timeline of the disease than the ill persons themselves. Partners were also more negative about the curability/controllability and the consequences of the disease. Moreover, dissimilarity in illness perceptions between persons with AD and their partners was associated with adaptive outcomes of the ill person (Heijmans et al., 1999). Illness perceptions were also different between people with Huntington’s disease and their partners, with partners’ beliefs about a longer duration of the disease and less belief in cure being associated with higher vitality rating of the ill persons (Kaptein et al., 2007), suggesting that partners who are realistic (even if negative) about the possibilities for cure and the long-lasting timeline of the disease might be beneficial.

In view of the persistent QoL impairments in people with pituitary disease (e.g. psychological complaints, personality changes, issues regarding sexuality), and the small number of studies in partners of people with pituitary disease, the aim of this study was to explore the impact of the pituitary condition on the lives of partners. In this study, we used focus group interviews, which incorporate group interaction as part of the method. Focus groups are particularly useful in exploring people’s experiences and knowledge, since it does not only assess what people think but also the reasons why they think that way and how they think (Kitzinger, 1995). Focus groups are commonly used in illness related topics, such as QoL and healthcare needs in people with chronic disease (Nicolson and Anderson, 2003; Patterson et al., 2012) and disease and treatment experiences in caregivers of ill people (Bove et al., 2016; Shapiro et al., 2013). We hypothesized that in accordance with the previous literature, partners of people with pituitary disease would also report a negative impact of the medical condition on their lives, including issues that are similar to partners of people with chronic disease in general, but potentially also disease-specific issues that are more relevant for partners of people with pituitary disease.

Methods

Participants

Partners who were willing to discuss the influence of the pituitary condition on their lives were recruited via their ill partners from the outpatient clinic of the Department of Endocrinology, Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands. Seven (35%) of the participants were partners of people with pituitary disease included in a previous focus group study (Andela et al., 2015a). Participant selection was aimed to result in a sample that would be representative of the partner population (e.g. regarding age, gender, education and duration since diagnosis). Four focus groups were formed per disease (CD, ACRO, NFA, PRL). Recommendations for focus group sizes vary considerably, but it has been stated that groups with three to eight participants work best for generating rich discussions (Braun and Clarke, 2013). Therefore, the present focus groups consisted of four to six partners (i.e. CD: P1–P5, ACRO: P1–P5, NFA: P1–P6, PRL: P1–P4).

All participants gave written informed consent. The Medical Ethical Committee of the LUMC approved the research protocol.

Study design

The focus group conversations were chaired by a health psychologist (moderator), experienced in group discussion (N.G.A.K.). The investigator (C.D.A., psychologist/researcher) observed the focus group meetings but did not participate in the discussions. Each of the four groups met twice for a discussion of ±2 hours. The focus group conversations took place in September 2012 and were held in a meeting room at the LUMC. The first meeting had the primary aim to get acquainted and to ensure a safe and confidential setting. Participants introduced themselves and then the discussion continued with open-ended questions suggested by the moderator. Based on the issues raised during the first meeting, a topic list was formulated for the second meeting (Supplement 1).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using an experiential thematic analysis following the six steps proposed by Braun and Clarke (2013). First, the audio-taped focus group conversations were typed out verbatim. Second, the transcripts were read and reread by the first and second author (J.T. psychologist/senior researcher, C.D.A. psychologist/researcher) in order to get familiar with the data, and potential items of interest were noted. Third, initial codes were produced from the data, and the entire dataset was coded. Discrepancies between coding were discussed and resolved by consensus (i.e. J.T., C.D.A.). Atlas.ti 6.2 software was used for managing and analysing the data. Fourth, codes were sorted into potential themes. Fifth, preliminary themes were reviewed, and a thematic map was created considering the formation of themes and subthemes. Extensive revision of themes was performed by splitting, merging and renaming themes. Finally, (sub)themes were further defined and named (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic variables of participants.

| Total (n = 20) | Patients’ pituitary

disease |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD (n = 5) | ACRO (n = 5) | NFA (n = 6) | PRL (n = 4) | ||

| Gender (M/F) | 9/11 | 3/2 | 3/2 | 2/4 | 1/3 |

| Age (years) | 48 (39–57) | 52 (36–56) | 46 (43–66) | 50 (38–61) | 40 (35–48) |

| Duration of follow-up (years) | 8 (3–13) | 8 (7–18) | 4 (3–22) | 5 (2–9) | 12 (3–18) |

| Education | |||||

| Low | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Medium | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| High | 12 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Living together | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Married | 17 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

CD: Cushing’s disease; ACRO: acromegaly; NFA: non-functioning pituitary adenoma; PRL: prolactinoma; M: male; F: female.

Data are presented as median (interquartile range (IQR)) or number.

Results

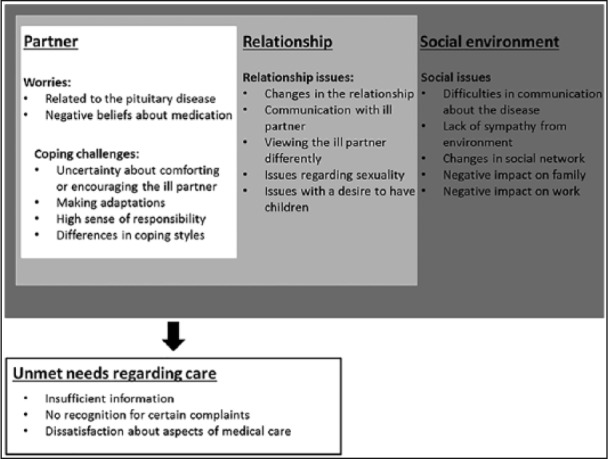

A total of 20 partners participated in the focus group discussions (11 females) and were present during both focus group meetings. Age ranged from 29 to 69 years (mean = 48 years). Duration of follow-up ranged from a few months to 27 years (mean = 9 years). After a total of eight focus groups (4 groups × 2 meetings) in our view, no new issues were discussed, and data saturation was reached. From the focus group conversations, five themes were derived: worries related to the pituitary disease and negative beliefs about medication, coping challenges, relationship issues, social issues and unmet needs regarding care (Figure 1). This study envisioned to evaluate the present impact of pituitary disease. Interestingly, during the focus group conversations, partners frequently referred to the stressful and intense moments experienced during the period of diagnosis, suggesting that this event still is an important issue. However, retrospectively evaluating this period of diagnosis did not match the scope of the research, and data about this topic were therefore not incorporated.

Figure 1.

The partner’s perspective of the impact of pituitary disease.

Worries related to the pituitary disease and treatment

Worries related to the pituitary disease

Partners reported concerns about the current health status of the ill partner. For example, worries about something happening to the ill partner (e.g. too low cortisol levels resulting in a life-threatening situation, which is named an Addisonian crisis) when the partner is not around and also concerns about how the ill partner is feeling that day. Partners also brought up concerns about the future, such as whether new problems will arise or whether existing problems will worsen. Another aspect was fear of recurrence; for example, when new symptoms are being experienced, partners wonder whether the new symptoms indicate tumour growth, recurrence of the tumour or possibly something else. Partners also mentioned concerns about the possible heritability of the disease:

The fear that you pass it on to your children is very scary. We have done some research but there is almost no chance, at least in our case. But my son had lots of headaches last year, then I’m like okay, well, now what? (PRL-P2)

Negative beliefs about medication

Partners reported worries related to medication, for example, about the effectiveness of suppressive medication in the future and uncertainty about possible side effects: ‘I am anxious about the medicine use in the future, what if the medication doesn’t work anymore at a certain moment, then you have to search for another treatment’ (ACRO-P4). They reported a strong negative attitude towards the medication, with the most negative thoughts mentioned in the PRL group. The partners commented on the negative effect of medication on the character of the ill partner (e.g. flattened affect, no highs and lows anymore): ‘The moment he stops his medication I see my old husband. But that disappears as soon as he starts again’ (PRL-P2) and ‘I think to myself: there goes another heap of poison’ (PRL-P1). Medication use was perceived as having a negative effect on sexuality:

There is certainly a big difference in sexuality between before and after the medication for the illness. That was quite difficult, but I knew there was that connection and that medication was the cause. I did not suffer from relationship problems or uncertainty, because I had that knowledge. (PRL-P4)

Coping challenges

Uncertainty about accommodating or encouraging the ill partner

Many partners indicated difficulty in deciding when to accommodate the complaints experienced by their partner (e.g. fatigue) and when to encourage their partner to manage certain complaints by encouraging engagement in specific activities. Partners indicated that this difficulty improved over the years. ‘It is difficult to determine when you need to be that shoulder to cry on, when you need to pull somebody up, or when to say “don’t be silly, get up, and do it”’ (CD-P5).

Making adaptations

Many partners reported adapting their own behaviour to accommodate the complaints of their ill partners. For example, taking on specific tasks and providing extra protection for their partner. ‘I try to protect her every now and then’ (NFA-P2) and (another partner) ‘We now have a young family, so that is very busy, it’s half a pace faster than he can handle’ (CD-P2). Partners tried to protect the ill partner by not talking about difficulties experienced at work, since this potentially could be distressing for the non-working ill partner. Limiting potential topics of discussion led to feelings of inequality in the relationship. Furthermore, partners adjusted certain activities to the situation at hand: ‘My partner no longer drives, I always have to. Sometimes I feel like a taxi driver’ (ACRO-P1) and ‘I cannot take her for a walk on the beach, because that won’t work. But I can take her for a walk in the city with a pair of crutches’ (ACRO-P4). Partners often felt that making such adjustments provided necessary support for the ill partner. They felt their ill partner was the weaker one. This is why partners were inclined to protect their ill partner: ‘you are the one taking the blows’ (ACRO-P1). Partners reported feeling inhibited by the consequences of the disease and feeling pressured to make certain decisions in specific situations. Interestingly, many partners were putting it all in perspective:

If my partner would be manic depressive, I would not recognize her. With her current medical condition, however, I can still recognize my wife, so it is still the same woman. This is incredibly helpful for me, because I can see whom I fell in love with. (ACRO-P1)

High sense of responsibility

Partners reported they felt more responsibility in multiple contexts, which may result in adaptation of their own behaviour (see previous section). For example, partners felt responsible when it came to being well-informed ‘because if something happens, you are the one who needs to act’ (NFA-P5). In addition, a (partial) loss of income of the ill partner may have resulted in a larger financial responsibility for the healthy partner. Furthermore, partners had difficulty determining their own limits. Many felt that they should show understanding and empathy and also that they should maintain their own well-being (i.e. being clear about their limits).

Differences in coping styles

Partners found it difficult when their own coping techniques did not match those of the ill partner. For example, the ill partner would rather not talk about the disease and deny certain consequences, while the partner may feel the need to talk about it (see also next section).

Relationship issues

Changes in the relationship

Relationship difficulties sometimes arose during active disease and treatment periods. Partners reported feelings of inequality and the emergence of perceptions of a counsellor–patient relationship. The skewed relationship usually returned to a balanced one over time. Some partners mentioned that their relationship became stronger because they fought together to get through the disease process: ‘Our relationship has become very strong, because we fought the disease together and we came through together’ (CD-P5). Other partners reported a lasting negative impact on their relationship, for instance, inequality on some fronts (i.e. there is still somewhat a counsellor–patient relationship) or a general change in the relationship ‘I find that it changes your relationships anyway, yeah, the positivity is gone’ (PRL-P4).

Communication with partner

Partners reported needing to express sensitivity in communicating when the ill partner was suffering from mood swings. Uncertainty about the ill partner’s response during mood swings often led to tensions. Partners reported being able to talk about most topics, although issues related to sexuality were harder to discuss.

Viewing the partner differently

Some partners reported viewing their partner differently. For example, partners found their ill partner less attractive due to the changes in their relationship (i.e. shifting towards a counsellor–patient relationship). However, partners also found their ill partner more beautiful, because they were proud of the way their ill partner coped with the consequences of the disease. Partners reported having great difficulty with the character changes of the ill partner (PRL) ‘She/he is still my best friend, but she/he changed from a very positive person to somebody who is very black-and-white’ (PRL-P2), while other partners reported a positive character change: ‘I tell my partner that he/she has changed considerably, became sweeter, and even more attractive to me’ (NFA-P3).

Issues regarding sexuality

Some partners reported that sex/intimacy with their ill partner improved compared to the past and that it became more valuable. Other partners reported that sex/intimacy decreased during active disease and that it recuperated but did not normalize ‘Our sex life took quite a hit’ (NFA-P3).

Issues with the desire to have children

Partners reported concerns about the inability to conceive, either currently or in the past: ‘You have a certain expectation about your life, and you need to adjust that expectation’ (PRL-P2).

Social issues

Difficulties in communicating about the disease

Difficulties in talking about the disease, as well as talking about potential consequences were reported. Partners had a hard time determining whom to tell about the disease. When partners decided to tell somebody about the disease, they found it difficult to explain what was going on: ‘It is like you lost your arm, which will never grow back. Other people then understand it cannot be reversed, because that is often the question’ (ACRO-P1). Some partners reported giving shorter answers over time when questions about the disease came up because they faced misunderstanding from people around them.

Lack of sympathy from the social network

Partners reported that people in their social network asked questions about the disease with the assumption that it would get better. Similarly, they felt that symptoms were downplayed by their social network: ‘When a friend says: sure, I experience the same symptoms every now and then, I think I am suffering from the same disease’ (NFA-P2) or ‘People in your social environment say: it’s not malignant, so it is nothing’ (PRL-P4). The social network does not understand why people with pituitary disease and their partners cannot participate in certain activities. Some partners reported loneliness due to the misunderstanding in their social network. Partners mentioned that the ill partner does not look sick, which could be the source of the misunderstanding in their social environment. Some partners also indicated that they are tired of being asked about the well-being of their ill partner and that they themselves are rarely asked about their own well-being.

Changes in social network

Partners reported that their social network had shrunk or at least had changed in a negative way.

Negative impact on family

Partners were concerned about the impact on their family. For example, expression of increased irritability around their children: ‘We currently experience that she/he is very tired and her/his patience runs out quickly. This is also towards the children’ (NFA-P4). Partners also mentioned that their children were concerned about the ill partner.

Negative impact on work

Partners reported they sometimes take time off work to accompany the ill partner to the doctor. Some partners even quit their job to keep everything afloat at home and to create stability (a somewhat forced choice).

Unmet needs regarding care

Insufficient information

Partners felt inadequately informed about the disease and its treatment and felt they did not get clear answers to some questions. Partners would have liked to be more involved in the information process:

If it is explained to me how it works psychologically, than I would have a lot less difficulty, less burden, and it would cost less energy. That would benefit the relationship when it comes to what you have to offer a partner. (PRL-P4)

Furthermore, partners mentioned that doctors should use less jargon when providing information to facilitate understanding.

No recognition for certain complaints

Partners experienced insufficient recognition for certain complaints, such as questions pertaining to the psychosocial aspects of the disease, questions about practical issues such as contraceptives and questions about medication use abroad. Partners also felt that certain aspects of the treatment were easily dismissed, for example, lifelong medication use ‘Your pituitary is damaged and it is possible that partial removal of the pituitary is necessary. However, this was easily dismissed with statements about “eliminating the effects of partial pituitary removal with medication,” and “everything will be alright”’ (NFA-P3).

Dissatisfaction about aspects of medical care

Partners would like additional guidance with psychosocial issues (e.g. medical psychologist, social worker, coach) or, for example, a help line to talk and get things off their chest. Partners in the PRL group mentioned they would like to learn the best way to deal with potential psychological symptoms of their ill partners. Partners would have liked more guidance during active disease and treatment. For example, guidance for children of parents with a pituitary adenoma and also advice on how they can best guide their children. There was also a need for peer support. Partners would like to receive help and guidance in how to best support the ill partner. Other partners indicated they do not want to be a ‘life coach’ for the ill partner, since this could disrupt the balance in their relationship.

Discussion

This explorative focus group study in partners of people with pituitary disease provided an overview of the impact of the pituitary disease on their lives. The main issues reported by partners were that they were worried about the pituitary disease, had negative beliefs about the medication and that they encountered challenges in coping with the consequences. Furthermore, partners experienced issues in their relationship and in their social environment. Considering aspects of medical care, they felt inadequately informed about the disease and its treatment, they experienced insufficient recognition for certain complaints and they would like to have additional guidance (e.g. psychological support).

Weitzner and Knutzen (1998) speculated about issues for caregivers of people with pituitary disease based on observations in caregivers for people with dementia or cancer (i.e. stress due to disruptive behavioural problems, for example, personality changes and changes in social support). Both aspects were reported by partners in this study; however, some partners considered the personality changes of their ill partner bothersome, while others perceived these changes rather positive. Similar to the results of the quantitative study of Dunning and Alford (2009) in partners of people with pituitary disease (Dunning and Alford, 2009), the partners in this study reported the negative effects of the mood swings and fatigue of their ill partners. They also reported the higher sense of responsibility and negative impact on their family life. However, enhanced relationships were also reported. Furthermore, the partners in the study of Dunning and Alford felt excluded from much of the decision-making process and reported that they had to rely on the information given by their ill partner. This issue somewhat resemble what the partners in this study reported, that is, they would have liked to be more involved in the information process. Furthermore, in a qualitative study in people needing testosterone replacement and their partners, it was observed that partners reported changes in their relationship, that is, they reported loneliness, less affection, and they felt unwanted sexually (Dunning and Ward, 2004). These observations are in accordance with our finding that partners reported that sex/intimacy decreased during active disease.

Partners reported unmet needs regarding care including insufficient information, no recognition for certain complaints and dissatisfaction about aspects of medical care. Health care professionals could play a role in fulfilling these unmet needs by first and foremost being aware of these unmet needs. This awareness could facilitate the communication with patients and partners and encouraging the provision of patient (and partner)-centred care. Furthermore, partners explicitly reported a need for additional guidance regarding psychosocial issues, such as support from a health psychologist, social worker or coach. Therefore, experts working in this field should be incorporated in the multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals taking care of patients with pituitary disease. In addition, a self-management programme for patients and their partners could support them to cope with the disease and its consequences together.

It should be noted that some of the issues reported by partners of people with pituitary disease are also observed in partners of people with other chronic diseases. For instance, in a recent focus group study in partners of people with prostate cancer, partners reported a need to be involved in the treatment process, reported issues in how to support one’s husband (who is experiencing a loss of masculinity), problems regarding incongruent coping responses between partners and constrained communication between partners (Wootten et al., 2014). Furthermore, mainly of the enlisted issues for partners of people with chronic disease, in general, in the review of Rees and O’Boyle (2001) were also reported by the partners of this study, for example, fear of the future, deterioration in the partner relationship and sex life, concern about suffering of the ill partner and social disruption (Rees et al., 2001).

Although the majority of the reported aspects may also be observed in partners of people with chronic disease in general, it is tempting to speculate that some of these issues are more pronounced in partners of people with pituitary disease. For instance, the negative beliefs about medication, since the majority of the patients need lifelong (daily) replacement therapy and/or suppressant medication. Issues regarding sexuality and the desire to have children can also be more pronounced considering the important role of the endocrine system in fertility and sexuality. Finally, we postulate that the reported lack of sympathy of the environment is more pronounced in partners of people with pituitary disease than in other chronic diseases, considering the fact that a pituitary adenoma is a rare disease and relatively unknown in society.

The limitation of research reflexivity could potentially be found in the previous research by our research group into the psychosocial impact of pituitary disease (Andela et al., 2015a, 2015b; Tiemensma et al., 2010a, 2010b, 2011; Van der Klaauw et al., 2008). Although we strongly attempted to approach the partners’ stories unprejudiced, it might be that our preconceived views of psychosocial issues in patients with pituitary disease have influenced the research process. Furthermore, we aimed to have a representative group composition that is able to reflect a broad range of experiences; however, selection bias may be inevitable. Future quantitative research is needed to examine well-being of partners of people with pituitary disease. This would provide the opportunity to examine how well-being of partners of people with pituitary disease relates to well-being of partners of people with other chronic diseases (Bergelt et al., 2008; Gottberg et al., 2014; McPherson et al., 2011), as well as whether illness perceptions of people with pituitary disease are similar to the perceptions of their partners.

In summary, this explorative focus group study in partners of people with pituitary disease illustrates the negative impact of pituitary diseases on the lives of partners. This study emphasizes the importance of not only paying attention to the psychosocial impact of people with pituitary disease during medical consultation but also to their partners. Furthermore, information obtained in this study can be used for the development of a disease-specific questionnaire for partners of people with pituitary disease, in order to quantitatively assess their well-being, as well as for optimizing psychosocial care not only for people with pituitary disease but also for their partners.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all partners for their participation in the focus group conversations.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Ipsen.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Reference

- Andela CD, Niemeijer ND, Scharloo M, et al. (2015. a) Towards a better quality of life (QoL) for patients with pituitary diseases: Results from a focus group study exploring QoL. Pituitary 18: 86–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andela CD, Scharloo M, Pereira AM, et al. (2015. b) Quality of life (QoL) impairments in patients with a pituitary adenoma: A systematic review of QoL studies. Pituitary 18: 752–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergelt C, Koch U, Petersen C. (2008) Quality of life in partners of patients with cancer. Quality of Life Research 17: 653–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biermasz NR, van Thiel SW, Pereira AM, et al. (2004) Decreased quality of life in patients with acromegaly despite long-term cure of growth hormone excess. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 89: 5369–5376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bove DG, Zakrisson AB, Midtgaard J, et al. (2016) Undefined and unpredictable responsibility: A focus group study of the experiences of informal caregiver spouses of patients with severe COPD. Journal of Clinical Nursing 25: 483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. (2013) Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners (1st edn). London: sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers OM, van der Klaauw AA, Pereira AM, et al. (2006) Quality of life is decreased after treatment for nonfunctioning pituitary macroadenoma. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 91: 3364–3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T, Alford F. (2009) Pituitary disease: Perspectives of patients and partners. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness 1: 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning TL, Ward GM. (2004) Testosterone replacement therapy – Perceptions of recipients and partners. Journal of Advanced Nursing 47: 467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottberg K, Chruzander C, Einarsson U, et al. (2014) Health-related quality of life in partners of persons with MS: A longitudinal 10-year perspective. BMJ Open 4: e006097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan FS, Strewler GJ. (1993) Basic and Clinical Endocrinology. New York: Appleton & Lange. [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans M, de Ridder D, Bensing J. (1999) Dissimilarity in patients’ and spouses’ representations of chronic illness: Exploration of relations to patient adaptation. Psychology & Health 14: 451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen DL, Heijmans M, Rijken M, et al. (2011) The development of and first experiences with a behavioural self-regulation intervention for end-stage renal disease patients and their partners. Journal of Health Psychology 16: 274–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein AA, Scharloo M, Helder DI, et al. (2007) Quality of life in couples living with Huntington’s disease: The role of patients’ and partners’ illness perceptions. Quality of Life Research 16: 793–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karavitaki N. (2012) Prevalence and incidence of pituitary adenomas. Annales D’Endocrinologie 73: 79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kars M, van der Klaauw AA, Onstein CS, et al. (2007) Quality of life is decreased in female patients treated for microprolactinoma. European Journal of Endocrinology 157: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger J. (1995) Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal 311: 299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. (1980) The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S. (ed.) Contributions to Medical Psychology (2nd edn). New York: Pergamon, pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson CJ, Wilson KG, Chyurlia L, et al. (2011) The caregiving relationship and quality of life among partners of stroke survivors: A cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 9: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Ostroff J, Winkel G, et al. (2005) Partner unsupportive responses, avoidant coping, and distress among women with early stage breast cancer: Patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychology 24: 635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson P, Anderson P. (2003) Quality of life, distress and self-esteem: A focus group study of people with chronic bronchitis. British Journal of Health Psychology 8: 251–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish JM, Lyng PJ. (2003) Quality of life in bed partners of patients with obstructive sleep apnea or hypopnea after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Chest 124: 942–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson P, Millar B, Desille N, et al. (2012) The unmet needs of emerging adults with a cancer diagnosis: A qualitative study. Cancer Nursing 35: E32–E40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie KJ, Weinman J. (2006) Why illness perceptions matter. Clinical Medicine 6: 536–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie KJ, Cameron LD, Ellis CJ, et al. (2002) Changing illness perceptions after myocardial infarction: An early intervention randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine 64: 580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees J, O’Boyle C, MacDonagh R. (2001) Quality of life: Impact of chronic illness on the partner. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 94: 563–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J, Wiglesworth A, Morrison EH. (2013) Views on disclosing mistreatment: A focus group study of differences between people with MS and their caregivers. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2: 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemensma J, Biermasz NR, Middelkoop HA, et al. (2010. a) Increased prevalence of psychopathology and maladaptive personality traits after long-term cure of Cushing’s disease. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 95: E129–E141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemensma J, Biermasz NR, van der Mast RC, et al. (2010. b) Increased psychopathology and maladaptive personality traits, but normal cognitive functioning, in patients after long-term cure of acromegaly. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 95: E392–E402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemensma J, Kaptein AA, Pereira AM, et al. (2011) Coping strategies in patients after treatment for functioning or nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 96: 964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Aken MO, Pereira AM, Biermasz NR, et al. (2005) Quality of life in patients after long-term biochemical cure of Cushing’s disease. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 90: 3279–3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Klaauw AA, Kars M, Biermasz NR, et al. (2008) Disease-specific impairments in quality of life during long-term follow-up of patients with different pituitary adenomas. Clinical of Endocrinology 69: 775–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verspaandonk J, Coenders M, Bleijenberg G, et al. (2015) The role of the partner and relationship satisfaction on treatment outcome in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychological Medicine 45: 2345–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzner MA, Knutzen R. (1998) The impact of pituitary disease on the family caregiver and overall family functioning. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 67: 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootten AC, Abbott JM, Osborne D, et al. (2014) The impact of prostate cancer on partners: A qualitative exploration. Psychooncology 23: 1252–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.