Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, drug–disease interactions, drug–drug interactions, hypertension, treatment strategies

Abstract

Background:

Caregivers encounter serious and substantial challenges in managing hypertension in patients with subclinical or clinical borderline personality disorder (BPD). These challenges include therapeutic conflicts resulting from harmful drug–drug, and drug–disease interactions. Current guidelines provide no recommendations for concurrent psychotropic and antihypertensive treatment of hypertensive BPD patients who are at even greater cardiovascular risk.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic literature review to assess the extent of available evidence on prevalence rates, cardiovascular risk factors, therapeutic conflicts, and evidence-based treatment recommendations for patients with co-occurring hypertension and BPD. Search terms were combined for hypertension and BPD in PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, and PsycINFO databases.

Results:

We included 11 articles for full-text evaluation and found a very high prevalence of hypertension and substantial cardiovascular risk in studies on co-occurring BPD and hypertension. However, we identified neither studies on harmful drug–drug and drug–disease interactions nor studies with treatment recommendations for co-occurring hypertension and BPD.

Conclusions:

Increased prevalence of hypertension in BPD patients, and therapeutic conflicts of psychotropic agents strongly suggest careful evaluation of treatment strategies in this patient group. However, no studies or guidelines recommend specific therapies or strategies to resolve therapeutic conflicts in patients with hypertension and BPD. This evidence gap needs attention in this population at high risk for cardiovascular disease.

1. Introduction

Hypertension increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and affects almost one-third of all people worldwide.[1] Prevalent psychiatric comorbidities such as depression, anxiety disorders, psychosis, and borderline personality disorder (BPD) elicit challenges in the treatment of hypertension and worsen outcomes.[2] Over 40% of patients in internal medicine emergency departments have hypertension and up to 10% of patients in psychiatric emergency departments have BPD suggesting an overlap of these disorders.[3,4] Specifically, 9% to 27% of patients with agitation in emergency departments are diagnosed with BPD.[5] Unfortunately, readmission rates are high for hypertension patients with psychiatric comorbidities, especially with personality disorders.[6]

Borderline personality disorder causes impulsivity, disturbed interpersonal interrelatedness, warped cognitive perceptions anger, anxiety, depression, tension, and a chronic feeling of emptiness.[7,8] Prevalence of BPD in the general population varies between 0.5% and 4%.[9–12] Persons with BPD make up to 6% of patients in primary care,[13] 25% of psychiatric outpatients, and 43% of psychiatric inpatients.[8,14] Unhealthy life styles, and lower socioeconomic status in BPD associate with poorer somatic health.[2,15] Comorbidities emerge earlier in persons with BPD,[16] and these may in turn worsen BPD. In addition, comorbidities increase health care utilization, prolong hospitalizations, and lead to a higher readmission rate, higher costs, and premature mortality.[17,18] BPD patients, even undiagnosed ones, often use mental and somatic health care in excessive, disrupted, uncontrolled and ineffective patterns and trajectories.[12] Contact with health care services occurs predominantly in acute crisis.[7] BPD-related trauma, drugs, self-harm, and suicide lead to frequent hospital readmissions.[19,20]

BPD predisposes patients to short-term worsening of existing hypertension due to autonomic stress dysregulation and the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress system.[21–23] Other predisposing factors include nonconcordance with antihypertensive therapy, and treatment plans.

Drugs used for the treatment of hypertension or BPD may potentially worsen the other condition. Psychotropic agents used for treating BPD symptoms increase the risk of cardiovascular disorders.[24] Prescription rates for psychotropic agents are high for persons with BPD,[9,10] with 54% BPD patients having ≥ 3 psychotropic agents concomitantly and 80% ≥ 2 respectively.[25] Chanen et al[7] reported that doctors prescribed psychotropic agents to 78% of BPD patients for more than 75% of the time over a 6-year period and polypharmacy occurred in 37% of these patients. In addition to drug–drug and drug–disease interactions between psychotropic agents, interactions also occur between psychotropic and antihypertensive agents.[24,26]

The prevalence of hypertension is higher in BPD patients than in the general population,[2] and hypertension may be underdiagnosed in this population. Antihypertensive drugs have neuropsychiatric side effects such as fatigue and depression and psychotropic agents have long-term cardiovascular side effects such as hypertension, weight gain, and metabolic changes.[27–30] Treatment of hypertensive BPD patients merits hence careful attention for such interactions.

The ACC/AHA et al guideline 2017 for the management of high blood pressure recommends caution in prescribing psychotropic agents to patients with hypertension because of their potential detrimental cardiovascular side effects.[31] Furthermore, drug affinities for histamine, dopamine serotonin, and muscarinic receptors are closely linked to cardiovascular risk accumulation, and patients with a history of heart disease, arrhythmia, or syncope, or family history of prolonged QT syndrome on early sudden death should not receive QT-prolonging antipsychotic agents.[26] However, to our knowledge, no guidelines address in detail the treatment of hypertension in patients with BPD.

Given the lack of guidelines for concurrent psychotropic and antihypertensive treatment of hypertensive BPD patients, we systematically reviewed the literature to assess currently available evidence on the prevalence rate of hypertension and BPD, and the cumulated cardiovascular risk of these 2 conditions in conjunction. We also systematically reviewed literature on potential therapeutic conflicts (i.e., harmful drug–drug and drug–disease interactions) and evidence-based therapeutic strategies for hypertension treatment in patients with BPD.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Literature search and screening

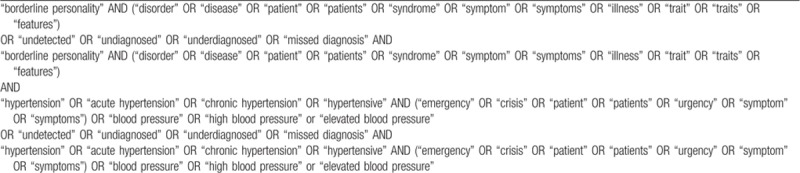

We performed a comprehensive qualitative systematic literature search following the PRISMA guideline 2009[32] on all publications until September 13, 2018, through the PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, and PsycINFO databases (Supplemental Table 1). We used search terms (“borderline personality”) AND (“hypertension”) including variations of the 2 terms (Table 1). We kept the search terms for the database queries as broad as possible to ensure maximal coverage of the literature. A Boolean operator “AND” combined the search terms through abstracts, keywords, and titles and free text. Consequently, we merged the selected articles of the 5 databases and subsequently removed duplicates by using EndNote X8 (Thomson Reuters). Ethical approval was not required since no patient-related data was acquired or analyzed in conducting this systematic review.

Table 1.

Search terms used in the systematic literature search for detection of co-occurrence of BPD and hypertension.

2.2. Selection criteria

Selection criteria included full-text articles written in English relating to both of these disorders and their respective or combined management (Table 1). We excluded articles on nonhumans and articles without abstracts. Since our focus was on adult patients, we excluded individuals under 18 years of age. We excluded also pregnant women because hormonal changes relating to pregnancy might transiently alter the psychiatric diseases and because we aimed to focus on the combination of long-term forms of BPD and hypertension. We also excluded comments, letters, and case studies. For completeness, it is however worth noting that the all-inclusive BPD- and hypertension-related search terms in this study did not generate any literature on individuals under 18 years of age, or on pregnant women who met the criteria for inclusion in the subsequent steps of this systematic review.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of publications

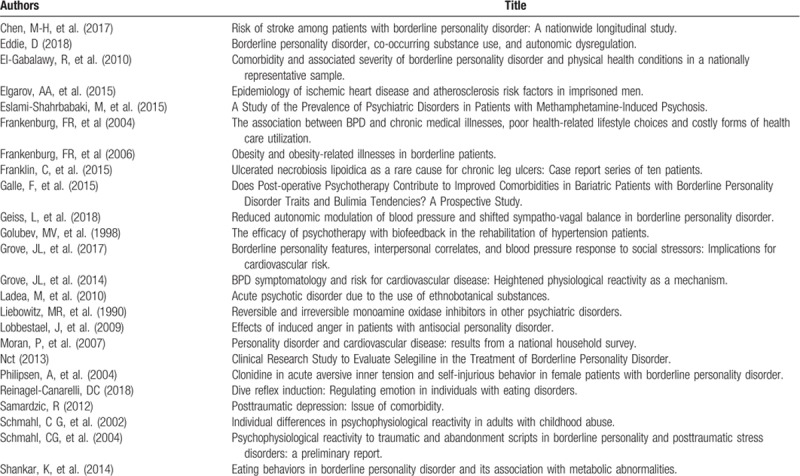

We identified 195 publications by searching for BPD and hypertension using PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO databases. After removal of duplicates, we included the 143 remaining publications in a 2-step evaluation procedure. In the first step, we evaluated the abstracts. Two independent authors, SMR and MC, selected abstracts for inclusion separately before discussing their inclusion together. No disagreements emerged. The selection of abstracts was based on the following criteria: the abstract contained at least 1 BPD-related term such as “borderline personality” and at least 1 hypertension-related term such as “high blood pressure,” as shown in Table 1. The first step resulted in 24 articles that included both hypertension- and BPD-related terms in the abstract (Table 2).[15,16,33–54]

Table 2.

Articles (n = 24) included after first evaluation step.

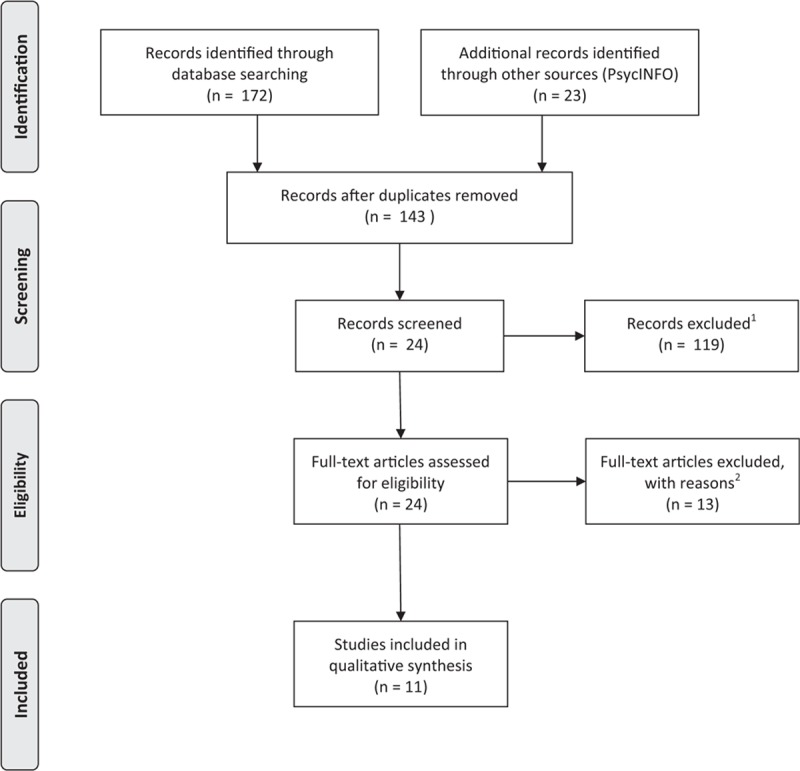

In the second step, we evaluated the full texts of these 24 articles for pharmacological treatment of either hypertension, BPD or both conditions and for drug–drug and drug–disease interactive effects. Of these articles, 11 were included in the analysis (Fig. 1, Table 3).[15,16,33–35,37,40,43,47,49,53]

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review process. The flow diagram presents the steps performed in the systematic search, in accordance with the PRISMA guideline 2009. The initial search of the 5 databases identified 195 publications with co-occurring “hypertension” and “BPD” terms. After removal of duplicates and publications with no co-occurrence of hypertension and BPD in their abstract, 24 publications were left for further evaluation and 11 articles were included in the analysis. BPD = borderline personality disorder.

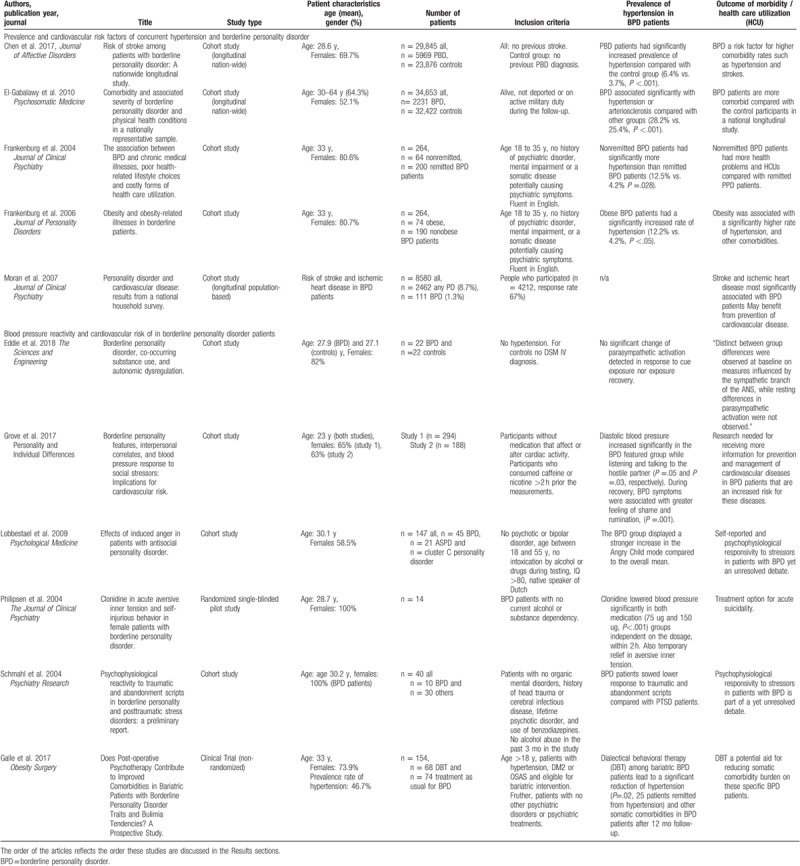

Table 3.

Articles included in the qualitative analysis.

3.2. Prevalence of concurrent hypertension and BPD

Prevalence of concurrent hypertension and BPD varied between 6.7% and 46.7% in 5 studies that reported prevalence rates.[16,33,34,37,40] Among studies on BPD patients, patients with an insufficiently controlled but treated BPD and BPD with obesity, had a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension compared with the control group, respectively (12.5% vs. 4.2%, P = .023,[16] and 12.2% vs. 4.2%, P < .05[37]). Obese BPD patients who were to undergo bariatric surgery had a 46.7% prevalence rate of hypertension.[40] A significantly higher prevalence of hypertension in BPD patients was also reported in 2 national longitudinal studies comparing BPD patients with other study participants (6.4% vs. 3.7%, P < .001[33] and 28.2% vs. 25.4%, P < .001[34], respectively). In 4 of these articles, BPD and hypertension were diagnosed by a physician,[16,33,37,40] and in one, both conditions were self-reported.[34] In summary, the rate of hypertension is higher among BPD patients, especially in patients with an active BPD.

3.3. Risk of cardiovascular disorders and screening for risk factors

BPD associates with an elevated risk of somatic, mainly cardiovascular morbidities in 3 population-based analyses.[15,33,34] After adjusting for age, sex, and confounders, Moran et al[15] reported increased risk of strokes and ischemic heart disease (OR: 8.5; 95% CI, 1.0–72.8 and OR: 7.2; 95% CI, 2.1–24.3, respectively) among BPD patients when compared with the general population without personality disorders. Chen et al[33] reported a significantly elevated rate of diabetes (4.2% vs. 1.9%, P < .001), dyslipidemia (6.2% vs. 3.5%, P < .001), and ischemic heart disease (2.0% vs. 0.5%, P < .001), and El-Gabalawy et al[34] reported significantly increased rates of diabetes (9.3% vs. 8.1%, P < .001) and obesity (33.6% vs. 27.1%, P < .001) in BPD patients. In BPD cohort studies, insufficiently controlled but treated PBD patients and obese BPD patients had more health problems compared with BPD patients without combination of these particular comorbidities.[16,37] The rate of diabetes and chronic back pain was significantly increased in insufficiently controlled but treated PBD patients (10.9% vs. 1.5%, P = .028 and 62.5% vs. 38.5%, P < .001) compared with remitted BPD patients.[16] The rate of diabetes and asthma was significantly increased among obese BPD patients compared with nonobese BPD patients (10.8% vs. 1.1%, P = .003 and 47.3% vs. 19.5%, P < .001).[37] Moran et al[15] suggested that BPD patients could potentially benefit from a prevention strategy for cardiovascular diseases including hypertension. El-Gabalawy et al[34] recommended that BPD patients should be carefully screened and treated for their diverse somatic health problems.

3.4. Changes in blood pressure levels among BPD patients

Psychological studies analyzing the effects of autonomic nervous system (ANS) activation in BPD patients showed contradicting results. One study demonstrated distinct differences in the sympathetic activation of the ANS in BPD patients.[35] This was shown by significant increases in skin conductance and heart rate for picture stimuli among BPD patients compared with controls. An analysis of BPD featured patients (n = 188) from Grove et al[43] reported elevated diastolic blood pressure levels in BPD-featured patients while listening and talking to a hostile partner (β = 0.16, t(142) = 1.95, P = .05, and β = 0.18, t(142) = 2.27, P = .03, respectively). Contrary to these findings, Schmahl et al[53] reported a lower ANS response to stressors in BPD patients. These patients were, however compared with posttraumatic disorder patients. Several articles stated that the responsivity of BPD patients to different stressors remains an unresolved debate,[47,53,55] and may potentially predict increased risk for cardiovascular disorder development.[43]

3.5. Strategies for treatment of concurrent hypertension and BPD

Clear guidelines for the treatment of co-occurring hypertension and BPD are still missing. However, some preliminary steps have been taken. An analysis on the effects of dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) among bariatric BPD patients resulted in a significant reduction of hypertension (P = .02, 25 patients remitted from hypertension), and other somatic comorbidities in patients who had undergone dialectical psychotherapy for 12 months, hence suggesting DBT as a potential aid for reducing somatic comorbity burden on this specific patient group.[40] One analysis on adverse inner tension in BPD patients (n = 22) demonstrated Clonidine to significantly lower blood pressure within 2 hours during an acute self-injurious situation.[49] However, this study did not report long-term effects of Clonidine on blood pressure levels. Based on the nascent literature, good psychiatric care positively affects treatment results of hypertension and other somatic comorbidities in BPD patients.[16,40,56]

3.6. Description of drug–drug or drug–disease interactions of co-occurring hypertension and BPD

Despite its importance, drug–drug or drug–disease interactions of co-occurring hypertension and BPD, and its therapy were not specifically addressed in any of these articles.

4. Discussion

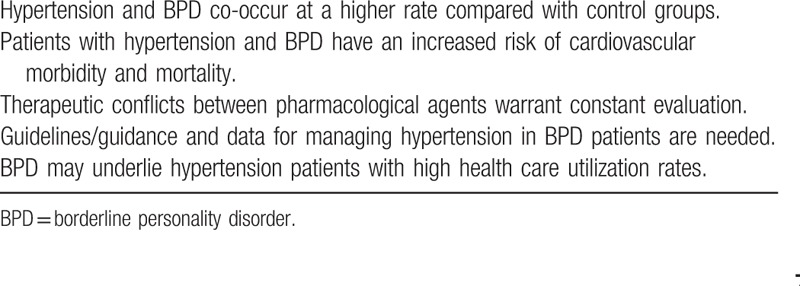

We have conducted a systematic literature review to assess evidence of the co-occurrence of hypertension and BPD, the associated combined cardiovascular risk, harmful therapeutic conflicts, and recommendations or therapeutic strategies for managing patients with hypertension and BPD. We summarized our main findings as key messages (Table 4). To our knowledge, this is the first such review.

Table 4.

Key messages.

The choice of search terms ensured an all-inclusive search of literature relating to hypertension and BPD. The combined use of the databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, and PsycINFO) warranted coverage of up to 97% of available publications.[57] Of the initially identified 143 articles, 11 were included in the analyses. These studies confirmed the increased rates of hypertension and cardiovascular risk factors among BPD patients. Surprisingly, none of these publications clearly reported the evidence of therapeutic conflicts (i.e., drug–drug or drug–disease interactions), or addressed the treatment strategies of patients with hypertension and BPD. Moreover, none of these publications referred to treatment recommendations for this particular patient group.

In cohort studies, the level of hypertension was significantly higher in BPD patients than in control patients.[16,33,34,37,40] Three studies reported a significantly earlier onset of hypertension in BPD patients.[16,33,34] Chen et al showed BPD to associate with strokes at a significantly higher rate and younger age. In this study, comorbidity burden was also associated with an increased patient suffering and a poorer quality of life.[16] Other screened studies showed an association of BPD with metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors.[58–61] Furthermore, 6 studies recommended a careful screening of BPD patients for diverse physical health conditions, especially for cardiovascular disorders in general,[34,44,58–60] 3 studies recommended treatment of these somatic comorbidities.[15,34,58] All these described results align with the finding of a suicidality-independent reduction of life-expectance of BPD patients by 9 to 13 years due to somatic comorbidity.[62]

A review of drug–drug interactions in 1995 already underlined the importance of risk assessment of concurrently prescribed antipsychotic and antihypertensive agents.[63] This suggestion extends to almost all hypertension patients with BPD, since most of these are under psychotropic medication.[9,10,64] In our study, we found no publications on harmful drug–drug or drug–disease interactions within or between psychotropic and antihypertensive agents in patients with hypertension and BPD. This is even more surprising as the co-occurrence of the 2 conditions is likely to be relatively prevalent in the population.

The lack of data in this patient population may be partially due to the fact that physicians prescribe psychotropic agents off-label for BPD patients. A few studies report from a long-term use of approximately 3 different psychotropic agents per BPD patient,[4,25] even though recommendations advise short-term single-drug therapy as a second-line treatment subsequent or adjunct to psychotherapy.[10,65,66] Additional comorbidities in these patients (e.g., diabetes and depression) and therefore the lack of homogeneous patient samples complicate the assessment of interactions between drugs used for hypertension and BPD treatment.[67,68] Heterogeneity in methodology and outcome measures across clinical trials also hinder assessment of treatment efficacy in BPD patients.[69,70]

Theoretically, potential drug–drug or drug–disease interactions between and within the groups of antipsychotic and antihypertensive agents could be collated from known databases in order to characterize the clinical relevance and severity of these therapeutic conflicts.[71] However, data on prescription practices in hypertension patients with BPD is lacking,[72] and may not specifically apply to these patients who tend to use medications in more disordered manners than average hypertension patients. Hypertension studies also exclude patients with severe psychiatric morbidities due to noncompliance and potential medication misuse.[73,74] Characterization of potential therapeutic conflicts for these patients is, hence, needed.

Harmful drug–drug and drug–disease interactions occur especially within but also between the groups of psychotropic and antihypertensive agents.[63] As an example of a drug–drug interaction between 2 psychotropic agents, the antipsychotic agent Quetiapine might increase the central-nervous toxicity and induce QT-prolongation effect of an antidepressant agent Citalopram.[71] The antipsychotic Clozapine induces weight gain for 4% to 31% of the patients predisposing patients with hypertension, representing a drug–disease interaction.[71]

The interaction of lithium and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors illustrates a drug–drug interaction between psychotropic and antihypertensive agents. Lithium is used in BPD patients for treatment of self-harming behavior and mood swings,[64,75] whereas ACE inhibitors form the backbone for treatment of hypertension.[31,76] Concomitant use of these pharmacological agents may increase the serum concentration level of lithium to a toxic level and cause life-threatening neurologic and cardiac symptoms including lethargy and arrhythmias.[77]

Psychotropic agents consistently prescribed for BPD in the long-term predispose BPD patients to drug–disease interactions that elevate the risk for hypertension and other cardiovascular disorders, such as weight-gain, diabetes, and increased lipid levels.[24,30,78] This applies for almost all psychotropic agents and their use should therefore be controlled and reevaluated regularly. Physicians should also be aware that antihypertensive agents could induce harmful psychiatric effects. For example, hydrochlorothiazide and other diuretics have been shown to cause anxiety, depressiveness, aggressiveness, and psychotic symptoms.[27,28] These symptoms may at least categorically overlap with and mimic BPD symptoms, and potentially hamper the accurate diagnosis of BPD.

Whether these potential conflicts translate into adverse outcomes in everyday medical practice remains to be investigated. It is also unclear whether drug management in patients with hypertension and BPD differs depending on the setting for example between internist and psychiatric emergency departments or different regions.

Emergency departments experience frequent health service use by BPD patients in periods of acute crisis due to self-harm and suicidal attempts.[79,80] Even in the absence of crisis, demands and pressures on patient–doctor interactions in hypertension patients with BPD may be overwhelming because of aggressiveness, impulsivity, anxiety, volatility, substance abuse, and poor adherence with scheduling or drug treatment.[4,79–84] This may influence diagnosis, therapy implementation, and drug management.[5,85–87]

Accurate diagnosis is essential for efficient management of BPD,[7,12,14] and failure to detect BPD could lead to ineffective or potentially harmful treatments.[88] It is unclear, whether or how many hospitalized patients remain undetected for both hypertension and BPD. Our systematic search showed this, since the addition of search terms for undetected diagnosis for hypertension and BPD did not produce additional results (Supplemental Table 1). In hypertension, major causes for underdiagnosis include poor awareness and lack of symptoms,[1,89,90] whereas underdiagnosis in BPD likely results in overlap with other psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and depression.[12,82,83,91] Stigma of the problematic diagnosis of BPD[62,92] probably also cautions physicians to give this diagnosis.[93]

BPD patients utilize healthcare, especially in the times of acute crisis.[19,20] Hypertension patients recurrently visiting psychiatric emergency departments should be screened for personality disorders.[6] Still, more data is needed on the prevalence and health service utilization patterns of hypertensive BPD patients during and outside times of BPD-related crisis in internist and psychiatric departments. Long-term polypharmacy of these patients demands clarification in outpatient settings between antihypertensive and psychotropic agents as well as between agents within these 2 medication groups. Cross-disciplinary expert opinion could be used for collecting guidance in situations with limited evidence-base. Moreover, substantial improvement in care for these patients in fragmented health care systems is needed, as this may lower adherence rates to diagnosis and therapy in both disorders.[1,94]

Physicians should be aware of the possibility of BPD in hypertension patients heavily utilizing healthcare. Due to the high prevalence and medication-induced risk of cardiovascular disorders in BPD and the potential harmful therapeutic conflicts within and between psychotropic and antihypertensive agents, physicians need to pay special attention when treating BPD patients, especially in conjunction with hypertension.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have identified 24 articles for full-text evaluation, of which 11 were included in the analysis. The prevalence of hypertension and especially the risk of early onset cardiovascular disorders are substantially increased in BPD patients due to mechanisms within BPD (e.g., HPA-dysfunction), and to the multiple long-term psychotropic medication of BPD patients (mean of 2.8 drugs). No article or guideline specifically examined effects of pharmacological treatment or addressed potential therapeutic conflicts in managing hypertension in patients with BDP. The lack of treatment recommendations highlights the importance of identifying evidence gaps in BPD.[95] The reported findings suggest that screening for hypertension in BPD patients is needed, and that BPD should be considered in patients with nonresponsive hypertension.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Saara M. Roininen, Marcus Cheetham, Edouard Battegay.

Data curation: Saara M. Roininen.

Investigation: Saara M. Roininen.

Methodology: Saara M. Roininen, Marcus Cheetham.

Project administration: Marcus Cheetham.

Resources: Edouard Battegay.

Supervision: Marcus Cheetham, Edouard Battegay.

Writing – original draft: Saara M. Roininen, Marcus Cheetham.

Writing – review & editing: Saara M. Roininen, Marcus Cheetham, Beatrice U Mueller, Edouard Battegay.

Edouard Battegay orcid: 0000-0001-9202-5034.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACC = American College of Cardiology, AHA = American Heart Association, BPD = borderline personality disorder, HPA = hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress system.

How to cite this article: Roininen SM, Cheetham M, Mueller BU, Battegay E. Unmet challenges in treating hypertension in patients with borderline personality disorder. Medicine. 2019;98:37(e17101).

The writers did not receive funding from external sources.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation 2016;134:441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. Personality disorders and medical comorbidity. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2006;19:428–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brody AM, Miller J, Polevoy R, et al. Institutional pathways to improve care of patients with elevated blood pressure in the emergency department. Curr Hypertens Rep 2018;20:30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pascual JC, Corcoles D, Castano J, et al. Hospitalization and pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder in a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:1199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shaikh U, Qamar I, Jafry F, et al. Patients with borderline personality disorder in emergency departments. Front Psychiatry 2017;8:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wagner JA, Pietrzak RH, Petry NM. Psychiatric disorders are associated with hospital care utilization in persons with hypertension: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2008;43:878–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chanen AM, Thompson KN. Prescribing and borderline personality disorder. Aust Prescr 2016;39:49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ten Have M, Verheul R, Kaasenbrood A, et al. Prevalence rates of borderline personality disorder symptoms: a study based on the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].NICE. Borderline Personality Disorder: Treatment and Management. Borderline Personality Disorder: Treatment and Management. Leicester (UK) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [10].NHMRC. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Borderline Personality Disorder. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chapman J, Fleisher C. Personality Disorder, Borderline. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Biskin RS, Paris J. Diagnosing borderline personality disorder. CMAJ 2012;184:1789–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gross R, Olfson M, Gameroff M, et al. Borderline personality disorder in primary care. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Skodol A, Stein MB, Hermann R. Borderline personality disorder: Epidemiology, clinical features, course, assessment, and diagnosis. 2018. URL: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/borderline-personality-disorder-epidemiology-clinical-features-course-assessment-and-diagnosis Accessed September 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Moran P, Stewart R, Brugha T, et al. Personality disorder and cardiovascular disease: results from a national household survey. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tomko RL, Trull TJ, Wood PK, et al. Characteristics of borderline personality disorder in a community sample: comorbidity, treatment utilization, and general functioning. J Pers Disord 2014;28:734–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Quirk SE, Berk M, Chanen AM, et al. Population prevalence of personality disorder and associations with physical health comorbidities and health care service utilization: a review. Personal Disord 2016;7:136–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hong V. Borderline personality disorder in the emergency department: good psychiatric management. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2016;24:357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kjaer JNR, Biskin R, Vestergaard C, et al. All-cause mortality of hospital-treated borderline personality disorder: a nationwide cohort study. J Pers Disord 2018;1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Carrasco JL, Diaz-Marsa M, Pastrana JI, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response in borderline personality disorder without post-traumatic features. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:357–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Austin MA, Riniolo TC, Porges SW. Borderline personality disorder and emotion regulation: insights from the Polyvagal Theory. Brain Cogn 2007;65:69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rinne T, de Kloet ER, Wouters L, et al. Hyperresponsiveness of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to combined dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing hormone challenge in female borderline personality disorder subjects with a history of sustained childhood abuse. Biol Psychiatry 2002;52:1102–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Abosi O, Lopes S, Schmitz S, et al. Cardiometabolic effects of psychotropic medications. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2018;36: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bridler R, Haberle A, Muller ST, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment of 2195 in-patients with borderline personality disorder: a comparison with other psychiatric disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015;25:763–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].De Hert M, Detraux J, van Winkel R, et al. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;8:114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Keller S, Frishman WH. Neuropsychiatric effects of cardiovascular drug therapy. Cardiol Rev 2003;11:73–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Huffman JC, Stern TA. Neuropsychiatric consequences of cardiovascular medications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2007;9:29–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Perez-Pinar M, Mathur R, Foguet Q, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors among patients with schizophrenia, bipolar, depressive, anxiety, and personality disorders. Eur Psychiatry 2016;35:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pina IL, Di Palo KE, Ventura HO. Psychopharmacology and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2346–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71:1269–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chen MH, Hsu JW, Bai YM, et al. Risk of stroke among patients with borderline personality disorder: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 2017;219:80–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].El-Gabalawy R, Katz LY, Sareen J. Comorbidity and associated severity of borderline personality disorder and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample. Psychosom Med 2010;72:641–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Eddie D. Borderline personality disorder, co-occurring substance use, and autonomic dysregulation. 2015. Thesis. Available at: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/51272/PDF/1/play/. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Eslami-Shahrbabaki M, Fekrat A, Mazhari S. A Study of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis. Addict Health 2015;7:37–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. Obesity and obesity-related illnesses in borderline patients. J Pers Disord 2006;20:71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Franklin C, Stoffels-Weindorf M, Hillen U, et al. Ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica as a rare cause for chronic leg ulcers: case report series of ten patients. Int Wound J 2015;12:548–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Geiss L, Hilz M, Hillemacher T, et al. Reduced autonomic modulation of blood pressure and shifted sympatho-vagal balance in borderline personality disorder. Neurol Psychiatr Brain Res 2018;29:9. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Galle F, Maida P, Cirella A, et al. Does post-operative psychotherapy contribute to improved comorbidities in bariatric patients with borderline personality disorder traits and bulimia tendencies? A prospective study. Obes Surg 2017;27:1872–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Elgarov AATZ, I, Elgarov MA, Kalmykova MA. Epidemiology of ischemic heart disease and atherosclerosis risk factors in imprisoned men. Russian J Cardiol 2015;122:42–7. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Golubev MV, Aĭvazian TA, Zaĭtsev VP. The efficacy of psychotherapy with biofeedback in the rehabilitation of hypertension patients. Vopr Kurortol Fizioter Lech Fiz Kult 1998;16–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Grove JL, Smith TW, Crowell SE, et al. Borderline personality features, interpersonal correlates, and blood pressure response to social stressors: implications for cardiovascular risk. Person Individual Differences 2017;113:38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Grove JL, Smith TW, Jordan KD. BPD symptomatology and risk for cardiovascular disease: heightened physiological reactivity as amechanism. Psychosomatic Med 2014;76:A-43. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ladea M, Lepadat M, Bran M, et al. Acute psychotic disorder due to the use of ethnobotanical substances. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2010;20:S606. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Liebowitz MR, Hollander E, Schneier F, et al. Reversible and irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors in other psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1990;360:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lobbestael J, Arntz A, Cima M, et al. Effects of induced anger in patients with antisocial personality disorder. Psychol Med 2009;39:557–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nct. Clinical Research Study to Evaluate Selegiline in the Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/nct01912391 2013. Accessed September 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Philipsen A, Richter H, Schmahl C, et al. Clonidine in acute aversive inner tension and self-injurious behavior in female patients with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1414–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Reinagel-Canarelli DC. Dive reflex induction: regulating emotion in individuals with eating disorders. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2018;79: [Google Scholar]

- [51].Samardzic R. Posttraumatic depression: issue of comorbidity. Eur Psychiatr 2012;27Suppl 1:1. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Schmahl CG, Elzinga BM, Bremner J. Individual differences in psychophysiological reactivity in adults with childhood abuse. Clin Psychol Psychother 2002;9:271–6. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Schmahl CG, Elzinga BM, Ebner UW, et al. Psychophysiological reactivity to traumatic and abandonment scripts in borderline personality and posttraumatic stress disorders: a preliminary report. Psychiatry Res 2004;126:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Shankar K, Devendran Y, Ruth S, et al. Eating behaviors in borderline personality disorder and its association with metabolic abnormalities. Indian J Psychiatry 2014;56:S52. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Schmahl CG, Elzinga BM, Bremmer JD. Individual differences in psychophysiological reactivity in adults with childhood abuse. Clin Psychol Psychother 2002;9:271–6. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Golubev MV, Aivazian TA, Zaitsev VP. [The efficacy of psychotherapy with biofeedback in the rehabilitation of hypertension patients]. Vopr Kurortol Fizioter Lech Fiz Kult 1998;16–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Harris JD, Quatman CE, Manring MM, et al. How to write a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:2761–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kahl KG, Greggersen W, Schweiger U, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with borderline personality disorder: results from a cross-sectional study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2013;263:205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ho CSH, Zhang MWB, Mak A, et al. Metabolic syndrome in psychiatry: advances in understanding and management. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2014;20:101–12. [Google Scholar]

- [60].John AP, Koloth R, Dragovic M, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Australians with severe mental illness. Med J Aust 2009;190:176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Greggersen W, Rudolf S, Brandt PW, et al. Intima-media thickness in women with borderline personality disorder. Psychosom Med 2011;73:627–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Cailhol L, Pelletier E, Rochette L, et al. Prevalence, mortality, and health care use among patients with Cluster B personality disorders clinically diagnosed in quebec: a provincial cohort study. Can J Psychiatry 2017;62:336–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Markowitz JS, Wells BG, Carson WH. Interactions between antipsychotic and antihypertensive drugs. Ann Pharmacother 1995;29:603–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Oldham JMG, Goin GO, Gunderson MK, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Psychiatric Association 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lieb K, Vollm B, Rucker G, et al. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry 2010;196:4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Stoffers J, Vollm BA, Rucker G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;CD005653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, et al. Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:1733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, et al. Axis II comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1998;39:296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Mercer D, Douglass AB, Links PS. Meta-analyses of mood stabilizers, antidepressants and antipsychotics in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: effectiveness for depression and anger symptoms. J Pers Disord 2009;23:156–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Binks CA, Fenton M, McCarthy L, et al. Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;CD005653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].UpToDate. Lexicomp Drug Interactions. 2018; Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/drug-interactions/ Accessed September 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. Mental health service utilization by borderline personality disorder patients and Axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for 6 years. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Gross CP, Mallory R, Heiat A, et al. Reporting the recruitment process in clinical trials: who are these patients and how did they get there? Ann Intern Med 2002;137:10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet 2005;365:82–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Belli H, Ural C, Akbudak M. Borderline personality disorder: bipolarity, mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics in treatment. J Clin Med Res 2012;4:301–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3021–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Masiran R, Abdul Aziz MF. Hypertensive bipolar: chronic lithium toxicity in patients taking ACE inhibitor. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Haueis P, Greil W, Huber M, et al. Evaluation of drug interactions in a large sample of psychiatric inpatients: a data interface for mass analysis with clinical decision support software. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;90:588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Cailhol L, Damsa C, Bui E, et al. [Is assessing for borderline personality disorder useful in the referral after a suicide attempt?]. Encephale 2008;34:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Koehne K, Sands N. Borderline personality disorder—an overview for emergency clinicians. Austral Emerg Nurs J 2008;11:173–7. [Google Scholar]

- [81].Kienast T, Stoffers J, Bermpohl F, et al. Borderline personality disorder and comorbid addiction: epidemiology and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Frias A, Baltasar I, Birmaher B. Comorbidity between bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder: prevalence, explanatory theories, and clinical impact. J Affect Disord 2016;202:210–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Beatson JA, Rao S. Depression and borderline personality disorder. Med J Aust 2013;1996 suppl:S24–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Pennay A, Cameron J, Reichert T, et al. A systematic review of interventions for co-occurring substance use disorder and borderline personality disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat 2011;41:363–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Bodner E, Cohen-Fridel S, Mashiah M, et al. The attitudes of psychiatric hospital staff toward hospitalization and treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Saunders KE, Hawton K, Fortune S, et al. Attitudes and knowledge of clinical staff regarding people who self-harm: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2012;139:205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr 2011;16:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Chanen AM. Borderline personality disorder in young people: are we there yet? J Clin Psychol 2015;71:778–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Korhonen PE, Kivela SL, Kautiainen H, et al. Health-related quality of life and awareness of hypertension. J Hypertens 2011;29:2070–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Walther D, Curjuric I, Dratva J, et al. High blood pressure: prevalence and adherence to guidelines in a population-based cohort. Swiss Med Wkly 2016;146:w14323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Beatson J, Broadbear JH, Sivakumaran H, et al. Missed diagnosis: the emerging crisis of borderline personality disorder in older people. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2016;50:1139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Sheehan L, Nieweglowski K, Corrigan P. The stigma of personality disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016;18:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Paris J. Why psychiatrists are reluctant to diagnose: borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4:35–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Weaver N, Coffey M, Hewitt J. Concepts, models and measurement of continuity of care in mental health services: a systematic appraisal of the literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2017;24:431–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Borschmann R, Henderson C, Hogg J, et al. Crisis interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;CD009353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.