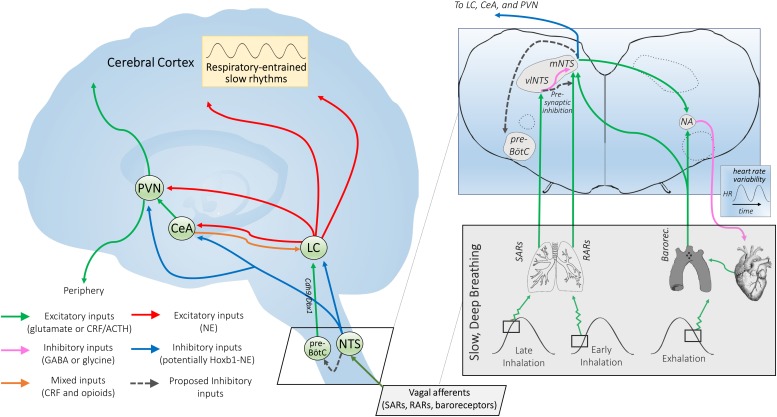

FIGURE 2.

Proposed mechanisms of NTS-mediated relaxation. Inset: Slowly-adapting pulmonary receptor (SAR) and rapidly-adapting pulmonary receptor (RAR) afferents project to the brainstem at the level of the medulla and innervate the parasympathetic relay nucleus, i.e., the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). That SARs project to a distinct anatomical NTS subregion from RARs and baroreceptors and are associated with a differentiable respiratory phenotype (slow and deep) is consistent with SARs serving a distinct function via a state transition in brainstem autonomic signaling. SARs project primarily to GABAergic inhibitory neurons in the ventrolateral subregion of the NTS (vlNTS) (Berger and Dick, 1987; Kubin et al., 2006), while RARs provide input to the more medial and caudal regions of the NTS (mNTS) (Kubin et al., 2006) to recruit noradrenergic output pathways. Aortic arch and carotid sinus baroreceptor primary afferents mimic RARs in their NTS termination patterns (Dean and Seagard, 1995), but are activated during exhalation instead of inhalation (Figure 1). Glutamatergic projections from the NTS are poised to regulate nucleus ambiguus (NA) cardiac vagal neurons (Neff et al., 1998). The ipsilateral mNTS is the major brain area sending projections to the cardioinhibitory region of the NA (Stuesse and Fish, 1984); though direct projections from the vlNTS have been observed, these are apparently less numerous and have not been shown for sake of clarity. Note that although projections from baroreceptor afferents to the NTS and the NTS to NA appear to cross contralaterally, this is for simplicity of illustration; the majority of these projections are ipsilateral. NTS projections may also feed in to the pre-Bötzinger complex (pre-BötC), potentially inactivating Cdh9/Dbx1 pre-BötC neurons that appear to activate the locus coeruleus (LC) via glutamatergic projections (Yackle et al., 2017; Vann et al., 2018), and thereby promoting calming. Outset: NTS projections to the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), and LC may link cardiorespiratory afferent activation to the effects of slow, deep breathing on stress reduction and attention. Noradrenergic NTS neurons project to downstream limbic areas, sending branching collaterals to the CeA and PVN (Petrov et al., 1993). Several nuclei in the NTS (along with the CeA) also project to the LC, potentially modulating central norepinephrine release (Van Bockstaele et al., 1996, 1999; Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003). NTS projections may serve to integrate autonomic responses with this circuitry and influence downstream targets of the LC (Van Bockstaele et al., 1999). The LC also provides noradrenergic projections to the CeA and PVN (Petrov et al., 1993), supporting the possibility of further signal integration at these higher-order hubs of the central autonomic network. Hoxb1 noradrenergic neurons (some of which originate from the NTS) provide a substantial input to the LC and peri-LC dendritic field (Chen et al., 2018) and are one neuronal subpopulation that could potently modulate LC activity, contributing to NTS-mediated relaxation. Interconnectivity between the two arms of this proposed neural pathway could influence peripheral and central release of neuropeptides through the PVN and widespread noradrenergic modulation of forebrain areas through the LC that together may impact arousal and responsiveness to stressors.