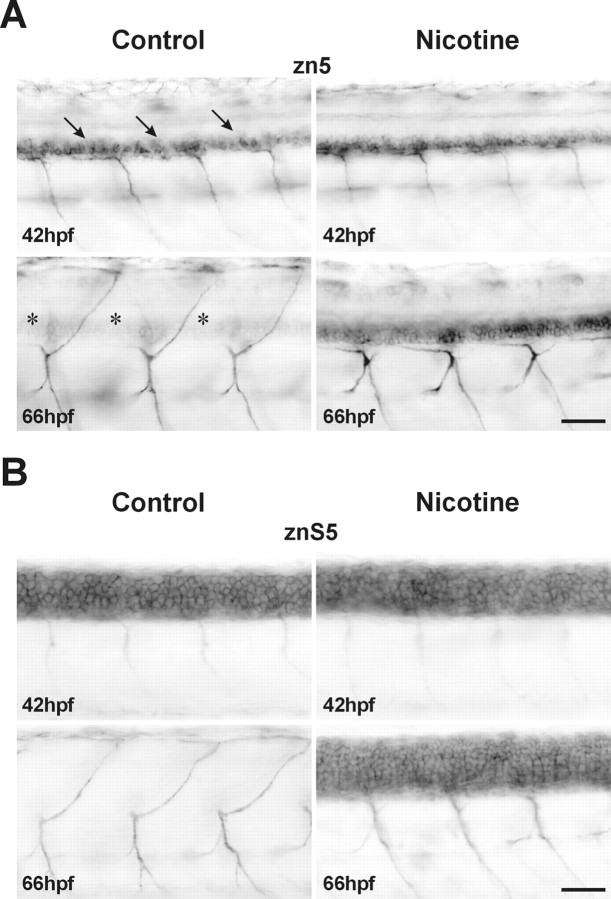

Fig. 6.

Immunocytochemistry confirms the nicotine-mediated delay of spinal motoneuron development. A, zn5 immunohistochemical photomicrographs of the caudal region of spinal cord from controls and embryos exposed to 33 μm nicotine from 22 to 42 and 66 hpf (42 hpf control, n = 9; 66 hpf control, n = 11; 42 hpf nicotine,n = 8; 66 hpf nicotine, n = 14). The zn5 antibody labels secondary motoneuron somata (arrows) as well as ventrally projecting motoneuron axons in control 42 hpf embryos. In control 66 hpf embryos, zn5 labels ventrally as well as dorsally projecting motoneuron axons, but somata labeling is faint (asterisks). In the 42 hpf embryo exposed to nicotine, zn5 labels secondary motoneuron somata and ventrally projecting motoneuron axons. In 66 hpf embryos exposed to nicotine, zn5 robustly labels secondary motoneuron somata and axons that project ventrally. Dorsally projecting axons are not detected by zn5 in the 66 hpf embryo exposed to nicotine. B, Experiments were performed as in A, but the znS5 antibody was used in place of zn5. In nonexposed 42 hpf embryos (n = 14), spinal neuron somata as well as ventrally projecting motor axons are detected by the znS5 antibody. At 66 hpf in control embryos (n = 23), znS5 detects ventral and dorsal motoneuron axons but not spinal neuron somata. In 42 hpf embryos exposed to nicotine (n = 13), spinal neuron somata as well as ventrally projecting motor axons are detected by the znS5 antibody. In 66 hpf nicotine-exposed embryos, znS5 detects ventral motoneuron axons and spinal neuron somata (n = 22). Scale bars, 40 μm.