Abstract

Altering neurotransmitter levels within the nervous system can cause profound changes in behavior and neuronal function. Neurotransmitter transporters play important roles in regulating neurotransmitter levels by performing neurotransmitter reuptake. It was previously shown that mutations in the Drosophila inebriated (ine)-encoded neurotransmitter transporter cause increased neuronal excitability. Here we report a further functional characterization of Ine. First we show that Ine functions in the short-term (time scale of minutes to a few hours) to regulate neuronal excitability. Second, we show that Ine is able to control excitability from either neurons or glia cells. Third, we show that overexpression of Ine reduces neuronal excitability. Overexpression phenotypes ofine include: delayed onset of long-term facilitation and increased failure rate of transmitter release at the larval neuromuscular junction, reduced amplitude of larval nerve compound action potentials, suppression of the leg-shaking behavior of mutants defective in the Shaker-encoded potassium channel, and temperature-sensitive paralysis. Each of these overexpression phenotypes closely resembles those of loss of function mutants in thepara-encoded sodium channel. These data raise the possibility that Ine negatively regulates neuronal sodium channels, and thus that the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine positively regulates sodium channels.

Keywords: neurotransmitter transporter, neuronal excitability, sodium channels, behavioral analysis, overexpression phenotypes, Drosophila

Regulation of neuronal ion channels by neurotransmitters is often mediated, directly or via second messengers, by G-proteins and G-protein-coupled neurotransmitter receptors (for review, see Hille, 1994; Wickman and Clapham, 1995). Unanswered questions remain as to the mechanisms by which altered neurotransmitter levels lead to changes in neuronal excitability and ultimately behavior. The cloning of inebriated(ine), which encodes a neurotransmitter transporter inDrosophila (Burg et al., 1996; Soehnge et al., 1996), enables the in vivo manipulation of transporter levels, and thus presumably the extracellular level of its substrate neurotransmitter. This provides a unique opportunity for in vivo dissection of the mechanisms by which neurotransmitters and their transporters regulate behavior and neuronal excitability.

The ine mutation was originally identified on the basis of increased neuronal excitability (Stern and Ganetzky, 1992). Double mutants defective in both ine and Shaker (Sh), which encodes a potassium channel α subunit channel (Baumann et al., 1987; Kamb et al., 1987; Tempel et al., 1987; Papazian et al., 1987), display a “downturned wings and indented thorax phenotype.” This appearance is identical to Sh mutants carrying either an additional mutation in eag, which encodes a potassium channel α subunit, or carrying a duplication of the paragene (termed Dp para+), which encodes a sodium channel (Loughney et al., 1989; Stern et al., 1990; Warmke et al., 1991; Zhong and Wu, 1991). Mutants defective in ineexhibit a second phenotype resulting from increased neuronal excitability: an increased rate of onset of a phenomenon termed long-term facilitation (Jan and Jan, 1978) at the larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ). This phenotype is also exhibited by several additional mutants in which neuronal excitability is increased (Stern and Ganetzky, 1989; Stern et al., 1990; Mallart et al., 1991; Poulain et al., 1994). These phenotypes suggest that ine mutations increase neuronal excitability by reducing K currents or increasing Na currents. The ine gene encodes two protein isoforms, Ine-P1 and Ine-P2, which share high homology to members of the Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporter family (Burg et al., 1996; Soehnge et al., 1996). Ine-P1 is identical to Ine-P2, except that it contains 300 additional amino acids in the N-terminal intracellular domain. However, it is not clear how mutations in a neurotransmitter transporter would cause increased neuronal excitability.

We report the use of transgenic Drosophila to dissect the mechanisms by which Ine and its substrate neurotransmitter control neuronal excitability. We show that ine can at least partially restore proper neuronal excitability when expressed in either glia or neurons, that ine can confer normal neuronal excitability within hours of expression, and that each Ine isoform is functional in the absence of the other (although Ine-P1 functions with greater efficiency). We also find that overexpression of inecauses phenotypes that are the opposite of those displayed byine loss-of-function mutants: these overexpression phenotypes closely resemble those conferred by loss of function mutations in the para sodium channel gene. These results suggest that the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine is an activator of sodium channels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks. ShKS133 is a dominant Shaker allele described previously (Kaplan and Trout, 1969; Jan et al., 1977) that causes rapid leg shaking while under ether anesthesia. All experiments in this paper involvingSh mutations use the ShKS133allele. para63 is a recessivepara allele that causes temperature sensitive (ts)-paralysis (Stern et al., 1990). MZ1580 is an insertion on the X chromosome of a P element transposon that carries the yeastGAL4 gene. This line expresses GAL4 in most embryonic glial cells (Hidalgo et al., 1995) and was kindly provided by the Andrea Brand lab (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK).gli-gal4 is an insertion of a GAL4-containing P element within the gliotactin gene, which expressesGAL4 in embryonic and larval peripheral glia (Auld et al., 1995; Sepp and Auld, 1999). This line was kindly provided by Vanessa Auld (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada).elav-gal4 is a P element insertion, provided by Kate Beckingham (Rice University) that carries the yeast GAL4gene driven transcriptionally by the promoter of the embryonic lethal abnormal visual system (elav) gene.ine1 bw carriesine1, which is a transcript null mutation (Soehnge et al., 1996) and a brown mutation as an eye color marker. Wild type (wt) represents the isogenicine+ parent ofine1. TM6Tb is a third chromosome balancer that carries the Tubby (Tb)marker, which was used as a dominant larval marker for selection of third instar larvae of the desired genotype.

Construction of the ine rescue lines. Theine gene expresses two transcripts: ine-RA, which encodes Ine-P1, and ine-RB, which encodes Ine-P2. For the heat shock rescue experiments, we used the ine-RA cDNA, which was placed under the control of a heat shock promoter to formhs-ine-RA (Burg et al., 1996). Transgenic flies carryinghs-ine-RA were generously provided by Martin Burg and William Pak (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN). Thehs-ine-RA chromosome was then crossed onto theine1 background to formine1; hs-ine-RA. FemaleSh; ine1 were crossed to maleine1; hs-ine-RA; sons of this cross were Sh; ine1, and carried one copy of hs-ine-RA. For the UAS-GAL4rescue experiments, full-length ine-RA (kindly provided by Martin Burg and William Pak, Purdue University) and ine-RBcDNAs were subcloned into the pUAST vector (Brand et al., 1994) via the EcoRI (by blunt-end ligation), andEcoRI/XhoI sites, respectively. Then, thepUAST-ine-RA and pUAST-ine-RB plasmids were injected into yw67c23 embryos for P-element mediated germ line transformation following standard protocols (Spradling, 1986). One transformant carrying theUAS-ine-RB on the third chromosome was obtained and used to construct ine1bw;TM6Tb/UAS-ine-RB. Two transformants carryingUAS-ine-RA were obtained. One of them carriedUAS-ine-RA on the third chromosome and was used to constructine1bw; UAS-ine-RA. The other carried UAS-ine-RA on the X chromosome and was used to construct Sh UAS-ine-RA; ine1bw. The MZ1580 line, the gli-gal4 line, and the elav-gal4 line were used to construct MZ1580;ine1bw,ine1gli-gal4, andine1bw; elav-gal4 respectively. Flies from these lines were crossed toine1bw; UAS-ine-RAand assayed for rescue. For the cross involving MZ1580, which is X-linked, sons from MZ1580; ine1bw mothers were tested.

Construction of the ine overexpression lines. For testing the effects of ine overexpression on larval motor neuron function, flies carrying UAS-ine-RA on their third chromosome were crossed to either the MZ1580 line or thegli-gal4 line. For crosses involving MZ1580, daughters from MZ1580 mothers were assayed. For testing the effects of ine overexpression on leg shaking, Sh MZ1580females were constructed and crossed to maleSh+; UAS-ine-RA. Sh MZ1580/+; UAS-ine-RA/+daughters were assayed. For testing the effects of ine overexpression on para63-conferred temperature sensitive paralysis, flies carrying UAS-ine-RAon their X chromosome were crossed onto thepara63 chromosome. Thenpara63 UAS-ine-RA females were crossed to male gli-gal4 to obtain sons of the genotypepara63 UAS-ine-RA; gli-GAL4/+.

Heat shock rescue experiment. Flies were raised in uncrowded bottles at 18°C and synchronized for eclosion by picking wandering third instar larvae every 4 hr and placing them into separate vials. Flies from these vials were then allowed to grow further at 18°C. Immediately before eclosion, the vials were transferred to 37°C and incubated for 1.5 hr, and then transferred to room temperature. Males that eclosed within 6 hr were collected, aged for 2 d and scored for the “downturned wings” phenotype.

Electrophysiology. Larvae for electrophysiological analysis were grown in uncrowded bottles at 21–22°C. Larvae were selected for experimentation only from bottles in which third instar larvae had just started to emerge. Dissections and nerve and muscle recordings were performed as described previously (Jan and Jan, 1976; Ganetzky and Wu, 1982; Stern and Ganetzky, 1989). Quinidine, when used, was bath applied at a concentration of 0.1 mm. Muscle cells 6, 7, 12, or 13 from abdominal segments 4 or 5 were used for measuring the rate of onset of long-term facilitation. Only muscle 6 was used for measuring the excitatory junctional potential (EJP) success rate. For these experiments, the dissections and recordings were performed at 21–22°C. For recordings of the amplitude of compound action potentials at elevated temperatures, a TC-324B Heater controller and a SH-27B inline solution heater (Warner Instrument Corporation, Hamden, CT) were used to heat the recording solution to the desired temperatures. Electrodes used for intracellular muscle recordings were pulled on a Flaming Brown micropipette puller. The tip resistances were 20–40 MΩ.

Behavioral analysis. For the ts-paralysis analysis, flies were raised at 18°C. For experimentation, the flies were transferred to vials partially submerged in a water bath at the designated temperature. The number of flies that became paralyzed within 15 min were counted. For the suppression of the leg-shaking phenotype ofSh mutants, flies were raised at room temperature. Newly eclosed flies were collected, aged for 2 d, etherized, and inspected for leg-shaking behavior under a dissecting microscope. A Nikon FX-35DX camera attached to a SMZ-U scope (Nikon, Melville, NY) was used for photography. To capture the movement of the legs (if any), films were exposed for ∼3 sec under a very dim light source.

RESULTS

Increased neuronal excitability in loss of functionine mutants

Although loss of function mutations in ine confer several phenotypes (Wu and Wong, 1977; Stern and Ganetzky, 1992; Burg et al., 1996) (Huang et al., 2002), this paper will focus on two phenotypes that result from increased neuronal excitability. The first phenotype is exhibited by double mutants defective in bothine and the potassium channel α subunit encoded byShaker (Sh). These Sh; ine double mutants exhibit a characteristic “downturned wings and indented thorax” appearance, which is not exhibited by wild type, or the Sh orine single mutants (Stern and Ganetzky, 1992). This appearance is identical to the appearance of Sh mutants carrying either a mutation in eag, which encodes a potassium channel α subunit distinct from Sh, or a duplication of the para gene (termed Dp para+), which encodes a Drosophilasodium channel (Loughney et al., 1989; Stern et al., 1990). Becauseeag mutations and Dp para+ each increase neuronal excitability (Ganetzky and Wu, 1982; Stern et al., 1990), it was suggested that this abnormal appearance results when the increased neuronal excitability of Sh mutants is even further increased by a second excitability mutation. The observation that ine mutations confer the identical phenotype suggest that ine mutations increase neuronal excitability as well, perhaps by either increasing sodium currents or reducing potassium currents. The mechanism by which the downturned wings phenotype is elicited by increased neuronal excitability is not known. However, the phenotype might result from hypercontraction of the dorsal longitudinal flight muscles (DLMs), which serve as wing depressors during flight and underlie the area of indented cuticle, as a result of increased neurotransmitter release from the motor neurons (C.-F. Wu and B. Ganetzky, personal communication).

Mutants defective in ine show a second neuronal excitability phenotype, which is manifested at the third instar larval NMJs. Wild-type Drosophila larval NMJs exhibit a phenomenon variously termed long-term facilitation (Jan and Jan, 1978) or augmentation (Wang et al., 1994). Long-term facilitation occurs after repetitive stimulation of the motor neuron at frequencies such as 5–10 Hz. At some point during this stimulation train, an excitability threshold is reached, and subsequent nerve stimulations then elicit motor nerve depolarizations that are more prolonged in duration, which causes increased Ca2+ influx, increased transmitter release, and an increase in the amplitude of the muscle EJP (Jan and Jan, 1978). Certain mutants that exhibit increased neuronal excitability also exhibit an increased rate of onset of long-term facilitation. These mutants include loss of function mutations inHyperkinetic (Hk), which encodes a K+ channel β subunit, overexpressors offrequenin (frq), which encodes an inhibitor of a K+ channel, and Dp para+ (Loughney et al., 1989; Stern and Ganetzky, 1989; Stern et al., 1990; Mallart et al., 1991; Poulain et al., 1994; Chouinard et al., 1995). The observation that inemutations also increase the rate of onset of long-term facilitation provides further evidence that ine mutations increase neuronal excitability by either increasing sodium currents or reducing potassium currents.

Short-term regulation of neuronal excitability by Ine and its substrate

Neurotransmitters can affect the properties of target neurons in an acute, short-term manner, or in a long-term manner often involving changes in gene expression (Kandel and Abel, 1995). The hyperexcitable phenotype exhibited by ine mutants could be a consequence of chronic overstimulation of the target neurons with the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine during development, leading to long-term increases in neuronal excitability. This effect could require changes in gene expression. Alternatively, the ine mutations could affect neuronal excitability in an acute, short-term manner (minutes to a few hours), which would not be expected to require changes in gene expression. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we investigated the ability of Ine-P1 to rescue the downturned wings phenotype of Sh; ine double mutants when induced transcriptionally during particular times of development. To accomplish this goal, the ine-RA cDNA was introduced into Sh; ine mutants under the control of a heat shock inducible promoter (Burg et al., 1996). Transcription of the ine gene was induced by heat shock at various times during development, and the ability to rescue the downturned wings phenotype of Sh; inedouble mutants was tested.

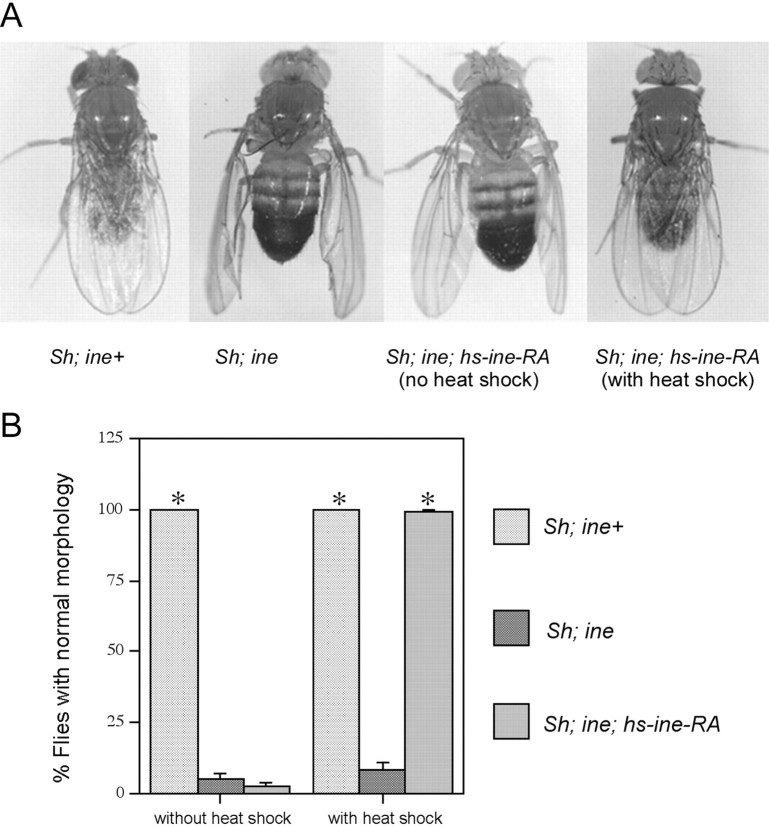

First we tested whether induction of Ine-P1 expression immediately before eclosion was sufficient for rescue. We found that rescue of the downturned wings phenotype occurred when flies carrying thehs-ine-RA were given only one single heat pulse immediately before eclosion. Flies that did not carry hs-ine-RA, or that carried hs-ine-RA but did not receive the heat shock, were not rescued (Fig. 1). These results suggest that ine expression is not required significantly before eclosion to control the downturned wings phenotype. We also found that induction of Ine-P1 expression after eclosion did not rescue the downturned wings phenotype (data not shown). The failure of rescue after eclosion perhaps occurs because after eclosion, DLM anatomy is fixed and no longer responds with structural changes to the reduced excitability conferred by ine-RA expression. These results indicate that ine is not required before the time of eclosion to affect the downturned wings phenotype.

Fig. 1.

A single pulse of Ine-P1 expression within 6 hr of eclosion is sufficient to rescue the downturned wings phenotype ofSh; ine double mutants. A, Representative flies of Sh; ine+, Sh; ine1, Sh; ine1; hs-ine-RA (without heat shock), and Sh; ine1;hs-ine-RA (with heat shock), showing the downturned wings phenotype of Sh; ine double mutant and rescue of this phenotype by expression of Ine-P1 from thehs-ine-RA construct. B, Quantification of the heat shock rescue experiments. n = 200 forSh; ine+,n = 80 for Sh; ine1 without heat shock;n = 132 for Sh; ine1; hs-ine-RA without heat shock; n = 85 for Sh; ine1 with heat shock; n = 178 for Sh; ine1;hs-ine-RA with heat shock. Error bars represent SEMs. *p < 0.001 versus Sh; ine1.

Expression of Ine-P1 in either neurons or glial cells rescuesine mutant phenotypes

Because the electrophysiological defects of ine mutants are observed in motor neurons (Stern and Ganetzky, 1992), targetedine expression only in neurons could be sufficient for rescue. Alternatively, ine could exert its effects on neuronal excitability from glial cells; often, transporters that perform reuptake of neurotransmitter released from neurons are located in neighboring glia. Finally, perhaps expression in either cell type could be sufficient for rescue. The latter possibility would be consistent for a neurotransmitter transporter, which acts on neurotransmitters in the extracellular space between adjacent cells. To test these possibilities, ine-RA expression was targeted either to neurons or to specific glia with specific GAL4 drivers and the UAS-ine-RA line.

Two GAL4 lines were used to target Ine-P1 expression to different subsets of glial cells. The MZ1580 line expresses Gal4 from stage 11 in the longitudinal glioblast and its progeny, and later in most other glial cells (Hidalgo et al., 1995). Thegli-gal4 line expresses the Gal4 protein specifically in peripheral glial cells (Sepp and Auld, 1999), which wrap the motor and sensory axons of peripheral nerves. We found that expression of Ine-P1 from an UAS-ine-RA construct driven by either of theseGAL4 lines was able to rescue fully both the downturned wings phenotype (Fig.2A) and the increased rate of onset of long-term facilitation phenotype (Fig.2B,C). Control lines carrying either theGAL4 construct alone or the UAS construct alone did not show significant rescue. Furthermore, as seen in Figure2C, the rescued lines required even more repetitive nerve stimulation than wild type for the onset of long-term facilitation. This observation raised the possibility that overexpression ofine with the GAL4 system could reduce neuronal excitability, which is a possibility investigated in more detail below. These results indicate that Ine-P1 can function effectively from glial cells.

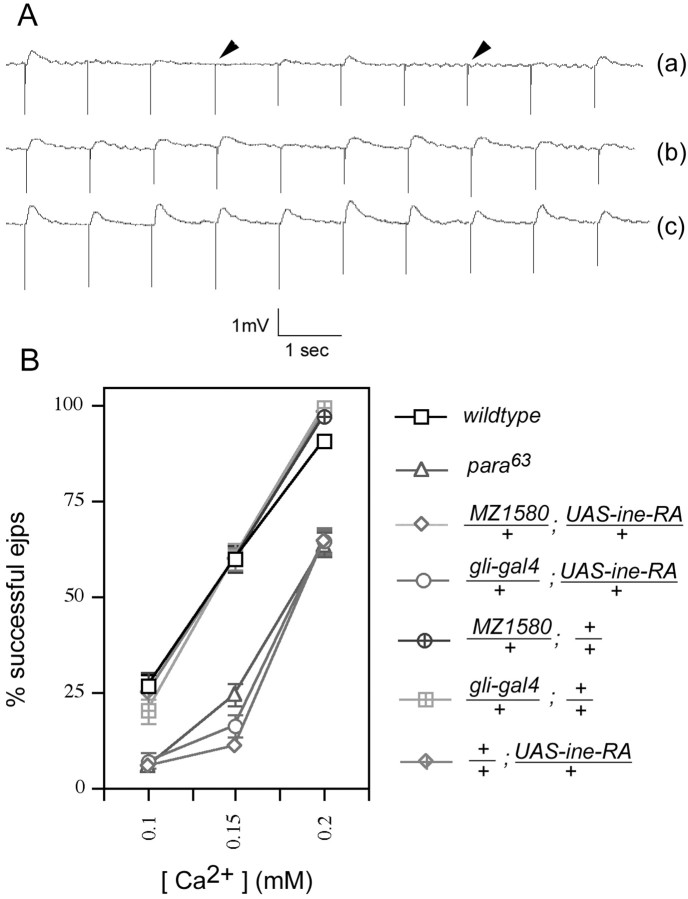

Fig. 2.

The ine mutant phenotypes are rescued by expression of Ine-P1 in glial cells. Two lines that expressGAL4 in glia, the MZ1580 line and thegli-gal4 line, were used to drive expression of Ine-P1 from the UAS-ine-RA construct. A, Rescue of the downturned wings phenotype. Percentages of flies with normal morphology are shown for each genotype. From top to bottom,n = 200, 97, 82, 130, 131, 104, and 42, respectively, for each genotype. *p < 0.001 versusSh/+; ine1. B,Representative traces showing the increased rate of onset of long-term facilitation in ine1 mutants compared with wild-type larvae, and rescue of this phenotype by reintroduction of Ine-P1 expression in glia. For these traces, GAL4represents MZ1580/+; ine1,UAS representsine1; UAS-ine-RA/+, andGAL4XUAS represents MZ1580/+; ine1‘; UAS-ine-RA/+. C. Quantification of the rescue of the fast long-term facilitation phenotype by expression of Ine-P1 in glia. The bath [Ca2+] was 0.15 mm. A 100 μm concentration of quinidine was present in the recording solution. The time required for the onset of long-term facilitation at the indicated stimulus frequencies is shown for each genotype. From top to bottom,n = 17, 8, 8, 10, 14, 10, and 13, respectively, for each genotype. Error bars represent SEMs.

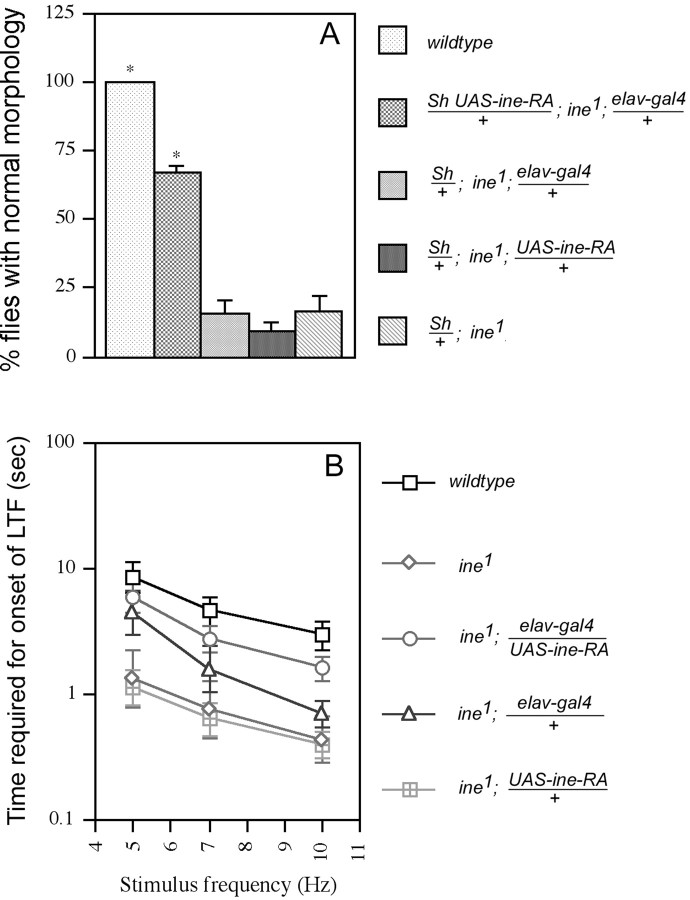

The elav-gal4 line, which expresses Gal4 specifically in neurons, was used for targeted Ine-P1 expression in neurons. We found that neuronal expression of Ine-P1 partially rescued the downturned wings phenotype, suggesting that ine can function in neurons as well as glia to control excitability (Fig.3A). Similarly, we found that expression of Ine-P1 in larval neurons partially rescued the long-term facilitation phenotype (Fig. 3B). For both phenotypes, the partial rescue conferred by neuronal expression was significantly different from the complete rescue that was conferred by glial expression (Fig. 2). Thus, ine can act in either a cell-autonomous or cell nonautonomous mode, which is consistent with the function of Ine as a neurotransmitter transporter. Furthermore, we conclude that the glia appear to be a more favorable site than neurons for Ine activity.

Fig. 3.

Targeted expression of Ine-P1 in neurons partially rescues the ine mutant phenotypes. A,Rescue of the downturned wings phenotype. Percentages of flies with normal morphology are shown for each genotype. From topto bottom, n = 292, 63, 104, and 42, respectively, for each genotype. *p < 0.001 versusSh/+; ine1. B, Rescue of the increased rate of onset of long-term facilitation. The bath [Ca2+] was 0.15 mm. A 100 μm concentration of quinidine was present in the recording solution. The time required for the onset of long-term facilitation at the indicated stimulus frequencies is shown for each genotype. From top to bottom,n = 17, 8, 19, 11, and 13, respectively, for each genotype. Error bars represent SEMs.

Ine-P1 and Ine-P2 rescue the ine mutant phenotypes with different efficiencies

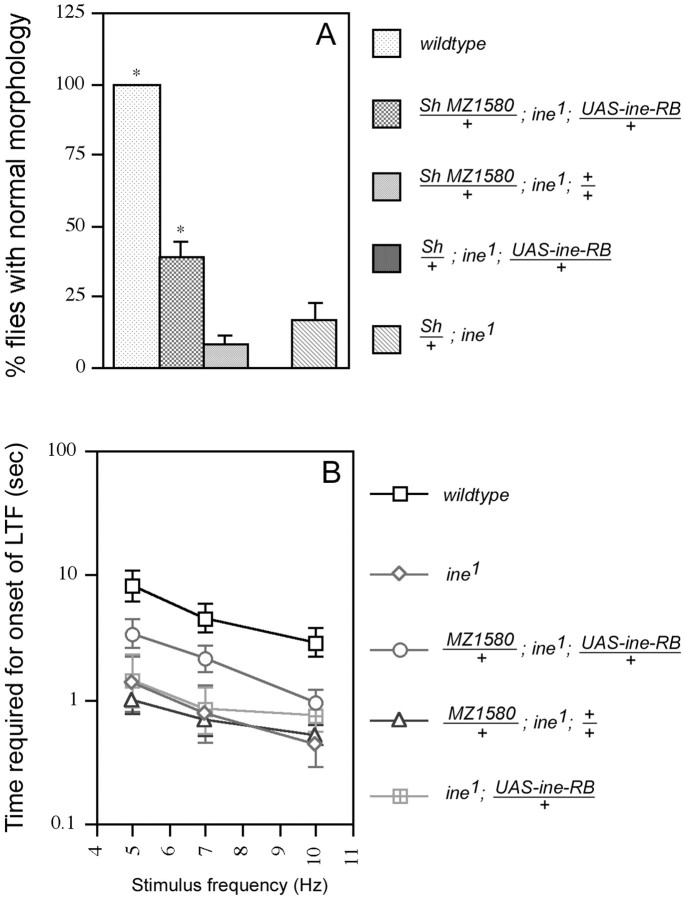

As demonstrated previously (Soehnge et al., 1996; Burg et al., 1996), ine expresses two transporter isoforms, Ine-P1 and Ine-P2. The N terminal intracellular domain of Ine-P1 is ∼300 amino acids longer than that of Ine-P2; the two isoforms are otherwise identical. Transcripts of the two isoforms were found to be colocalized in both the nervous system and the fluid reabsorption system of the flies (Soehnge et al., 1996; Huang et al., 2002). An N-terminal domain of the length of Ine-P1 is unusual for a member of this protein family and raised the possibility that this domain performs a function unrelated to neurotransmitter transport that is required for the control of neuronal excitability. If so, then Ine-P2, which lacks this extended N terminus, might be unable to function in the absence of Ine-P1. To test this possibility, we expressed Ine-P2 in glia by using the MZ1580 GAL4 line to drive expression ofUAS-ine-RB. We found that unlike Ine-P1, which fully rescued the ine phenotypes, Ine-P2 rescued the inephenotypes only partially (Fig. 4). For example, 94% of the Sh; ine flies carryingMZ1580 and UAS-ine-RA were rescued for the downturned wings phenotype (Fig. 2A), whereas only 39% of the Sh;ine flies carrying MZ1580 andUAS-ine-RB exhibited rescue (Fig. 4A). Similarly, ine mutant larvae carrying both MZ1580and UAS-ine-RB exhibited only a partial rescue of the increased rate of onset of long-term facilitation (Fig.4B); this degree of rescue was significantly different from the extent of rescue of ine mutants carrying both MZ1580 and UAS-ine-RA (Fig.2B). Thus, the presence of Ine-P2 alone provides someine activity, but Ine-P2 alone is much less effective than Ine-P1 alone.

Fig. 4.

Expression of the Ine-P2 isoform in certain glial cells partially rescues the ine mutant phenotypes.A, Rescue of the downturned wings phenotype. Percentages of flies with normal morphology are shown for each genotype. Fromtop to bottom, n = 97, 130, 35, and 42, respectively, for each genotype. *p < 0.01 versus Sh/+; ine1. B, Rescue of the increased rate of onset of long-term facilitation. The bath [Ca2+] was 0.15 mm. A 100 μm concentration of quinidine was present in the recording solution. The time required for the onset of long-term facilitation at the indicated stimulus frequencies is shown for each genotype. From top to bottom,n = 17, 8, 10, 14, and 8, respectively, for each genotype. Error bars represent SEMs.

Overexpression of Ine mimics the phenotypes of paraloss of function mutants

It was proposed previously that loss of ine function results in defective reuptake of a neurotransmitter, and thus to increased persistence of the transmitter in the synaptic cleft. This increased persistence, in turn, was proposed to cause overstimulation of signaling pathways that would ultimately increase motor neuron excitability (Soehnge et al., 1996). If so, then we would predict that overexpression of Ine might confer the opposite effect: a more rapid clearance of the transmitter, reduced stimulation of signaling pathways controlling excitability, ultimately leading to reduced neuronal excitability. To test this hypothesis, we overexpressed Ine-P1 by crossing the GAL4 drivers MZ1580 orgli-GAL4 to UAS-ine-RA in an otherwise wild-type background. For convenience, overexpression of Ine-P1 will be denotedOverine+ in the following discussion.

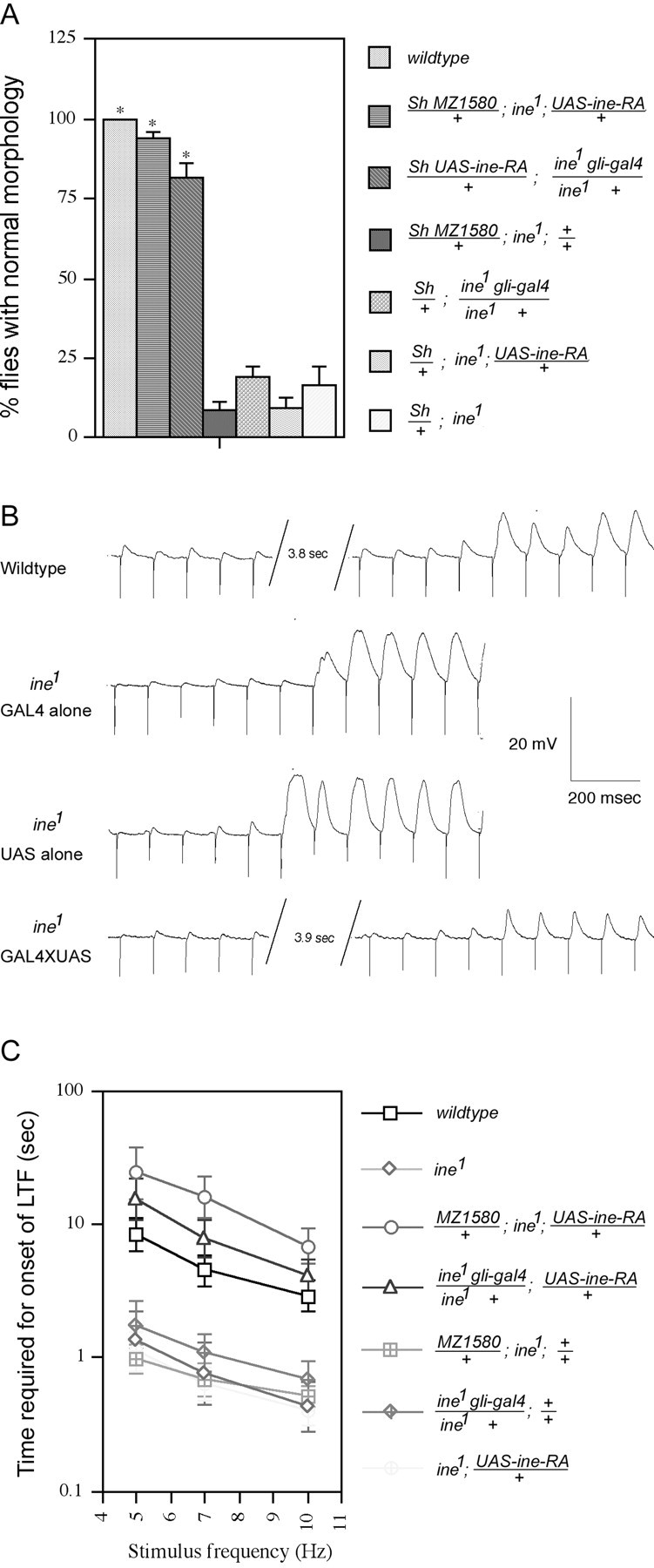

Suppression of Sh mutant phenotypes byOverine+

Previous studies showed that ine mutations enhance the phenotype of Sh mutants, leading to a downturned wings phenotype (Stern et al., 1992). We found thatOverine+ confers the opposite phenotype: suppression of the hyperexcitability phenotype of Sh mutants (Fig. 5A). In particular, whereas Sh mutants shake their legs vigorously after ether anesthesia, Sh MZ1580; UAS-ineRA flies exhibited greatly reduced leg shaking (Fig. 5A). Control Sh lines carrying only the MZ1580 construct, or only theUAS-ine-RA construct, exhibited a similar leg-shaking behavior to Sh mutants (Fig. 5A). The reciprocal interactions of ine− andOverine+ with the Sh mutation are consistent with previous observations in which it was found that hyperexcitability mutations, such aseag-and Dp para+, enhance the phenotypes of Shmutants, whereas mutations that reduce excitability, such aspara loss of function mutations, suppress Shphenotypes (Ganetzky and Wu, 1982; Stern et al., 1990) (Table1).

Fig. 5.

Overexpression of Ine-P1 confers phenotypes that are opposite to those conferred by loss of Ine. A,Overexpression of Ine-P1 (Overine+) suppresses this leg-shaking phenotype. Sh mutants shake their legs vigorously while under ether anesthesia. When photographing these flies with a long exposure time, the boundary of their legs becomes blurry because of the rapid leg movement (a–c).Overine+ suppresses this leg-shaking phenotype; thus the legs of Sh; Overine+ flies appear clearly in the pictures (d). B, Delayed onset of long-term facilitation at the larval neuromuscular junction. The bath [Ca2+] was 0.15 mm. A 100 μm concentration of quinidine was present in the recording solution. The time required for the onset of long-term facilitation at 10 and 7 Hz stimulus frequencies is shown for each genotype. From top to bottom,n = 17, 10, 9, and 10, respectively, for each genotype. Error bars represent SEMs. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001, versus wild type.

Table 1.

Genetic interactions of several excitability mutations with mutations in Sh

| Genotype | EnhancesSh | Suppresses Sh |

|---|---|---|

| para− | √ | |

| Dp para+ | √ | |

| eag− | √ | |

| ine− | √ | |

| Overine+ | √ |

Increased rate of onset of long term facilitation inOverine+

Overine+ also confers reduced excitability of the larval motor neuron. In contrast to the increased rate of onset of long-term facilitation observed in inemutants, Overine+ larvae showed a decreased rate of onset of long-term facilitation (Fig. 5B). For example, whereas wild-type larvae required only 2.9 sec of 10 Hz nerve stimulation to induce long-term facilitation,Overine+ larvae required 8.4 sec. Similarly, whereas wild-type larvae required only 4.5 sec of 7 Hz stimulation to induce long-term facilitation,Overine+ larvae required 24.2 sec. Finally, most of the Overine+ larvae (8 of 10 tested) failed to exhibit long-term facilitation even after 90 sec of 5 Hz stimulation, whereas most wild-type larvae (11 of 17 tested) were able to induce long-term facilitation under these conditions (data not shown).

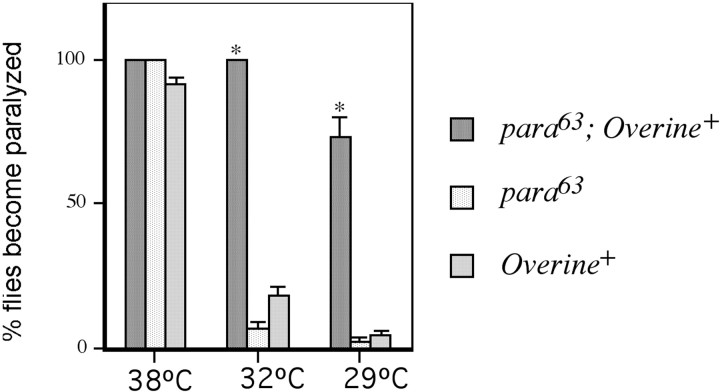

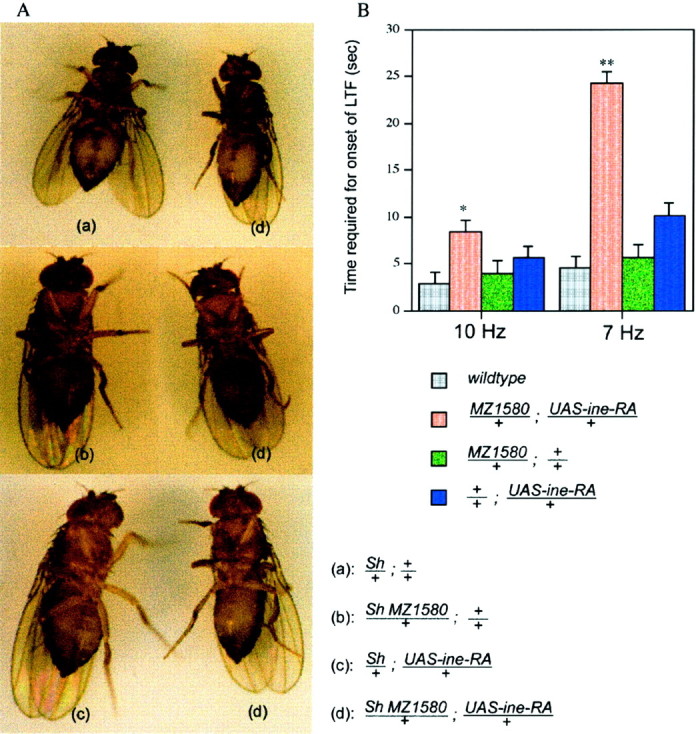

Overine+ causes temperature-sensitive paralysis

The decreased neuronal excitability observed inOverine+ larvae could be a consequence of decreased sodium channel activity. Mutants with decreased sodium channel activity, such as para, tipE,mlenap, Kinesin heavy chain,and axotactin often show a ts paralytic phenotype (Suzuki et al., 1971; Wu et al., 1978; Kulkarni and Padhye, 1982; Jackson et al., 1984; O'Dowd and Aldrich, 1988; Kernan et al., 1991; Gho et al., 1992;Hurd and Saxton, 1996; Yuan and Ganetzky, 1999; Ganetzky, 1984) (for review, see Ganetzky and Wu, 1986). These mutants, but not wild type, become paralyzed very quickly (within seconds or minutes) after placement at the elevated temperature, which can range from ∼29 to 38°. Generally, more severe reductions in sodium currents lead to a reduction of the temperature required to induce the paralysis. We found that Overine+ also confers ts paralysis. In particular, 92% of flies carrying both the UAS-ine-RAand the gli-gal4 constructs became paralyzed after transfer from 18 to 38° (Fig. 6), whereas flies carrying only the UAS-ine-RA construct or only thegli-gal4 construct did not show this paralysis.

Fig. 6.

Overine+interacts synergistically with para63: enhancement of the temperature sensitive paralysis phenotype in the double mutant. Flies of the indicated genotypes were raised at 18°C. At the time of experimentation, they were transferred from 18°C to the indicated temperatures. The number of flies of each genotype that became paralyzed within 15 min were counted. n = 41 for para63; Overine+. n = 90 forpara63. n = 133 for Overine+. Error bars represent SEMs. *p < 0.001 versuspara63.

Overine+ enhances the temperature-sensitive paralytic phenotype ofpara63

Mutations affecting neuronal excitability often display synergistic interactions (Ganetzky and Wu, 1982; Ganetzky, 1984, 1986;Stern et al., 1990; Hurd and Saxton, 1996). BecauseOverine+ and some paramutations cause ts paralysis, we tested a possible synergistic interaction between the two. In particular, we assayed for ts paralysis in flies combined for Overine+ andpara63, which is a partial loss of function mutation in para that confers ts paralysis (Stern et al., 1990) (Fig. 6). Although almost allpara63 andOverine+ mutants become paralyzed at 38°, only 2.2% of the para63 flies and 4.5% of the Overine+ flies became paralyzed when placed at 29°C. However, when the gli-gal4and UAS-ine-RA constructs were cointroduced into thepara63 background, to form theOverine+para63 combination, 73% of the flies became paralyzed at 29°C. Furthermore, whereas only 6.7% of thepara63 flies and 18% of theOverine+ single mutant became paralyzed, respectively, when placed at 32°C, all of thepara63;Overine+ double mutants tested became paralyzed (Fig. 6). This result demonstrates that strong synergistic enhancement occurs between Overine+ andpara63.

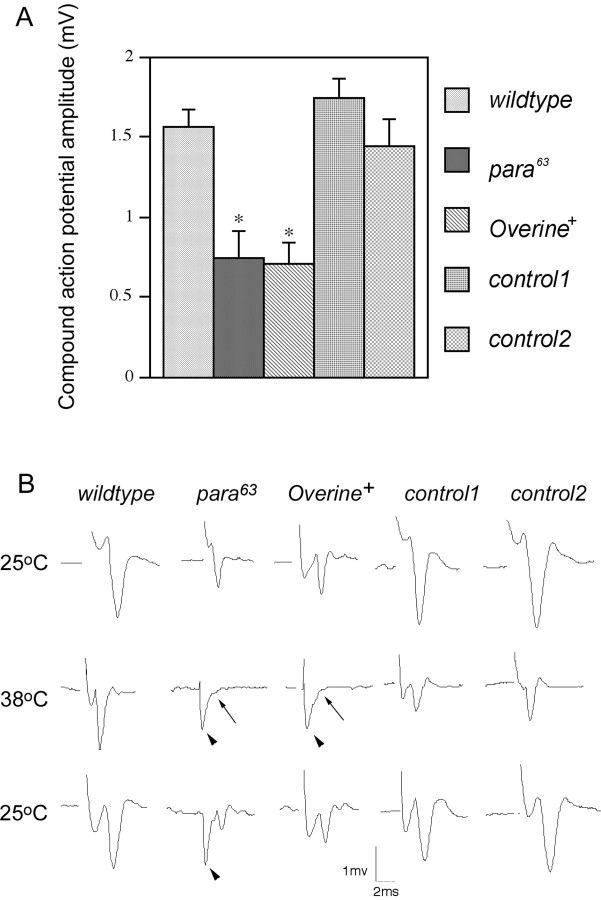

Increased failures of evoked transmitter release inOverine+ and para63 neuromuscular junctions

The resemblance of Overine+ topara63 is manifested not only at the behavioral level but also at the electrophysiological level. Compared with wild type, both para63 andOverine+ larvae exhibit a higher frequency of failures in evoked transmitter release from larval motor nerve terminals when bathed in buffer containing any of three different low [Ca2+] (Fig.7A,B). For example, at an external [Ca2+] of 0.15 mm, wild-type larval motor nerve terminals fail to release neurotransmitter after ∼40% of nerve stimulations, whereas for Overine+ andpara63, the failure rate is 90%. This phenotype reflects a presynaptic defect: the amplitude of miniature EJPs (mEJPs) is unchanged by Overine+ orpara63 (data not shown). Furthermore, the amplitude of successful EJPs is unaffected inOverine+ orpara63 larvae at the lowest [Ca2+] tested (0.1 mm), for which only failures or releases of single vesicles occur (Table 2). We interpret this increased failure rate to result from an axonal action potential of attenuated amplitude, which reduces the consequent nerve terminal Ca2+ influx, and thus reduces the probability of synaptic vesicle release. This interpretation predicts that Overine+ orpara63 should shift the Ca2+/transmitter release curve to the right, which is in fact what is observed (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Reduced success rate of EJPs at low bath [Ca2+] in para63and Overine+. A,Representative traces of EJP recordings fromOverine+ larvae (a) and control larvae (b, c). The stimulus frequency for these traces was 10 Hz. Arrowheadshows failure of EJP response. Bath [Ca2+] was 0.15 mm. B, Quantitation of the success rate of EJPs for each genotype at the indicated [Ca2+]. Larval nerves were stimulated at a frequency of 1 Hz, and 25 responses were averaged per nerve. Nerves from seven larvae were tested for every data point (175 responses total per data point). Error bars represent SEMs.

Table 2.

Ejp amplitude evoked by the release of a single vesicle is unaffected by para63 orOverine+

| Genotype | Mean ejp amplitude (mV) |

|---|---|

| wild type | 0.78 ± 0.06 |

| para63 | 0.72 ± 0.04 |

| Overine+(1) | 0.71 ± 0.08 |

| Overine+(2) | 0.79 ± 0.05 |

Average amplitudes of successful ejps evoked by nerve stimulation in the presence of low (0.1 mm) bath [Ca2+] in larvae of the indicated genotypes. Under these conditions, most successful ejps result from the release of a single vesicle of transmitter. Only successful ejps were included in this calculation.Overine+(1) indicates overexpression ofine driven by the MZ1580 gal4 line.Overine+(2) indicates overexpression ofine driven by the gli-gal4 line. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Data were collected from at least seven larvae for each genotype. Larvae were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and in the legend to Figure 7.

Further evidence for an attenuated action potential amplitude inOverine+ orpara63 was obtained from extracellular recordings of compound action potentials of the motor and sensory axons of the segmental nerve. The compound action potential is the additive output of action potentials fired by each axon in the nerve bundle in response to nerve stimulation. We found that at the permissive temperature of 21–22°C, both Overine+flies and para63 larvae showed compound action potential of reduced amplitude compared with wild type (Fig.8A,B). Furthermore, at the restrictive temperature of 38°, at which bothOverine+ andpara63 adults exhibit paralysis, bothOverine+ andpara63 larvae showed complete loss of compound action potentials. The loss was reversed when the temperature was lowered to the permissive temperature (Fig. 8B). The temperature-sensitive loss of action potential propagation was reported for other mutants showing reduced sodium currents as well (for review, see Ganetzky and Wu, 1986; Wu and Ganetzky, 1992) (Table3). This loss of action potentials is presumably related to the temperature-sensitive paralytic phenotype that these mutants exhibit. Compound action potentials of reduced amplitude at the permissive temperature is also a feature of mutants defective in Khc, which encodes kinesin heavy chain: this phenotype was suggested to result at least in part from a reduction in axonal sodium channels as a consequence of defective axonal transport (Gho et al., 1992). Taken together, these results suggest that overexpression of Ine-P1 reduces sodium channel activity and that the substrate neurotransmitter of the Ine transporter might control a signaling pathway that ultimately targets sodium channels.

Fig. 8.

Reduced compound action potentials amplitudes inpara63 andOverine+. Larvae were raised in bottles at 18°C and were transferred to room temperature for the experiments. Two suction electrodes were placed along the segmental nerve. One was placed close to the free end of the nerve to apply the depolarizing stimulus, whereas the other was placed close to the NMJ to record the compound action potential. For each larva tested, the initial compound action potential recordings were taken at a temperature between 20 and 25°C. Then the temperature was raised to between 38 and 39.5°C (<2 min was required for this temperature elevation), and recordings of evoked compound action potentials were continued. If failures were observed, the temperature was lowered to between 20 and 25°C, and recordings were continued to enable the recovery of the compound action potentials to be monitored. Recovery generally occurred very quickly after lowering of the temperature. If no failure was observed within 10 min at 38–39.5°C, then the temperature was lowered to between 20 and 25°C, and recordings were continued. The bath [Ca2+] was 1 mm for these recordings. A, Reduced compound action potential amplitude inpara63 andOverine+ mutants. TheOverine+ line shown here carries bothgli-gal4 and UAS-ine-RA, whereas control 1 carries only gli-gal4, and control 2 carries onlyUAS-ine-RA. n = 7 for wild type,n = 6 for para63,n = 8 forOverine+, n = 8 for control 1, and n = 7 for control 2. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.001 versus wild type.B, Representative traces showing failure of compound action potential in the para63 and theOverine+ larvae at the restrictive temperature. The top 25°C trace marks the first recording taken between 20 and 25°C for each genotype, themiddle 38°C trace marks the recording taken at 38–39.5°C, and the bottom 25°C trace marks the recording after the return to 20–25°C. Arrowheadsindicate stimulus artifact. Arrows indicate failure of compound action potential.

Table 3.

Common behavioral and electrophysiological phenotypes of mutations that reduce sodium channels

| Genotype | Overine+ | para | mlenap | tipE | Khc | Axo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ts-paralysis | 3-a | 3-a | 3-a | 3-a | 3-a | 3-a |

| Enhancement ofpara | 3-a | NA | 3-a | 3-a | 3-a | ND |

| Increased ejp failure rate | 3-a | 3-a | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Decreased axonal action potential amplitude | 3-a | 3-a | ND | ND | 3-a | ND |

| Failure of axonal action potentials at the restrictive temperature | 3-a | 3-a | 3-a | 3-b | ND | 3-a |

The mutant exhibits the corresponding phenotype.

The mutant does not exhibit the corresponding phenotype*.

NA, Not applicable; ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

Here we describe the manipulation in vivo of the expression level of the Drosophila ine-encoded neurotransmitter transporter and determine the effects of this manipulation on behavior and neuronal excitability. We found that Ine is active when expressed in either glia or neurons, and is required only in the short-term (with a time scale of a few hours or less) to regulate neuronal excitability. We also found that the two Ine isoforms are both functional, although Ine-P1 (the long form) appears to be more active than Ine-P2 (the short form). Finally, we found that overexpression of ine confers phenotypes that closely resemble those conferred by loss of function mutations in thepara-encoded sodium channel gene. Proposed models for the control of motor neuron excitability by Ine are discussed.

The time course of Ine function

Neurotransmitters can control the excitability of a target neuron either in a rapid, and rapidly reversible manner or in a long-term manner, often involving changes in gene expression. For example, at the Aplysia sensorimotor synapse, 5-HT application can affect the sensory neuron in both a short-term and long-term manner. In the short term, 5-HT application causes increased excitability of the sensory neuron by cAMP-dependent inhibition of a potassium channel (Kandel and Schwartz, 1982). Long-term exposure, in turn, leads to activation of gene expression by the CREB transcription factor (for review, see Kandel and Abel, 1995). We have found that one aspect of the neuronal excitability phenotype of inemutants, the “downturned wings” phenotype of Sh;inedouble mutants, can be reverted by a single pulse of ineexpression induced immediately before eclosion (Fig. 1). This result suggests that Ine is required only in the short term to restore this particular phenotype. Furthermore, this result suggests that any long-term changes in nervous system development that might occur inine mutants are not sufficient to confer the downturned wings hyperexcitable phenotype. This result further implies that one or more of the ine mutant electrophysiological defects also results from lack of Ine in the short term.

Possible sites of Ine function

We suggest that Ine could affect motor neuron excitability by acting within neurons (motor or interneurons) or the surrounding glia. We showed that targeted expression of ine in either neurons alone or peripheral glia alone was sufficient to rescue at least partially the ine mutant phenotypes. Glial cells seem to be a more favorable site for Ine function, because targeted expression ofine in the peripheral glia fully rescued the inemutant phenotypes (Fig. 2), whereas targeted expression ofine in neurons using the elav-gal4 driver only partially rescued the mutant phenotypes (Fig. 3). It is also possible that the difference in rescue efficiency is caused by inadequate expression of Gal4 protein by elav-GAL4: however, this possibility is unlikely because the same elav-GAL4 driver expresses sufficient Gal4 within motor neurons to confer a strongpumilio overexpression phenotype in the presence ofUAS-pumilio (B. Schweers, K. Walters, and M. Stern, in preparation).

Properties of the two Ine isoforms

The ine gene expresses two transporter isoforms, Ine-P1 and Ine-P2, which differ only at their N termini. Ine-P1 has an unusually long N terminal intracellular domain consisting of ∼300 amino acids. This long N terminus is uncommon among members of the Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporter family and raises the possibility that this domain might perform a function that is distinct from neurotransmitter transport but is required for the control of neuronal excitability. If so, then Ine-P2, which lacks the long N terminal intracellular domain, would be unable to perform this function and would be unable to confer any ine+activity in the absence of Ine-P1. Our demonstration that each isoform is able to perform ine+ function on its own does not support this possibility. The Ine-P2 isoform performs less effectively than Ine-P1, which raises the possibility that the long N terminus of the Ine-P1 isoform might be required for efficient transporter activity. For example, the N terminus might be required for proper localization, stability, or activation of the transporter.

ine overexpression phenotypes

Increased neuronal excitability could be a consequence of increased sodium channel activity or decreased potassium channel activity. The phenotypes of flies overexpressing ine (calledOverine+) suggest that inenegatively regulates sodium channels because the phenotypes ofOverine+ flies closely resemble the phenotypes of para loss of function mutants. In particular,Overine+ suppresses the leg-shaking behavior of Sh mutants, confers temperature sensitive paralysis in adults, eliminates the compound action potentials in larval peripheral nerves at the restrictive temperature, decreases the amplitude of these compound action potential at the permissive temperature, and decreases the success rate of EJPs evoked at the larval neuromuscular junction in low external [Ca2+] (Figs. 5-8). Each one of these phenotypes is conferred as well by loss of function mutations inpara (Suzuki et al., 1971; Siddiqi and Benzer, 1976; Wu and Ganetzky, 1980; Stern et al., 1990; this study). Furthermore, most of these phenotypes have been reported for mutations in other genes that reduce sodium channels. These genes includemlenap, Kinesin heavy chain, axotactin, and tipE (Wu et al., 1978; Kulkarni and Padhye, 1982; Ganetzky, 1986; Gho et al., 1992; Feng et al., 1995; Hurd and Saxton, 1996; Yuan and Ganetzky, 1999) (Table 3). These data strongly suggest that Ine and its substrate neurotransmitter regulate excitability of the motor neuron by modulating sodium channels. In this view, the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine activates sodium channel activity, and Ine attenuates this activation by performing neurotransmitter reuptake.

Possible models of the Ine regulatory system

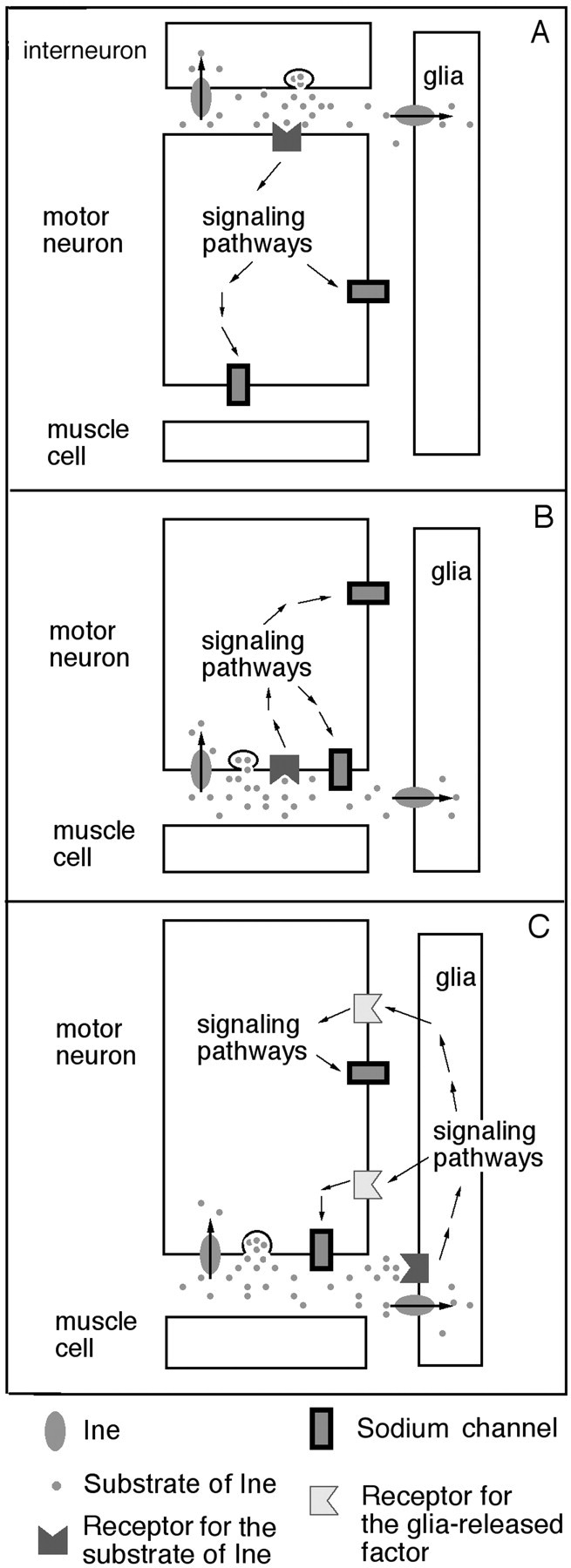

We suggest three possible mechanisms to account for these data. The first mechanism (Fig. 9A) suggests that the substrate transmitter of Ine is released from an interneuron that synapses onto the motor neuron. Binding of the transmitter to its receptors in the motor neuron triggers a signal transduction pathway that serves to activate sodium channels in the motor neuron. The Ine transporter, which resides either in the interneuron, the motor neuron, or a neighboring glia, terminates this signaling pathway. In our preparation for electrophysiology recordings, the motor neuron cell body, together with any upstream interneurons, are severed from the axon and removed. If the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine is released from the interneuron then it must exert its effects on motor neuron excitability before the dissection. This possibility does not necessarily contradict our hypothesis that Ine affects excitability in a short-term manner, because there are several molecular mechanisms that can operate on the required time scale. For example, CAM kinase II autophosphorylation causes its signaling pathway to remain active for a prolonged period, even in the absence of the original stimulus (Giese et al., 1998).

Fig. 9.

Possible mechanisms for the control of axonal sodium channels by Ine. A, Interneuron–motor neuron signaling. An interneuron releases the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine at a synapse with a motor neuron. This neurotransmitter activates a signaling pathway that ultimately leads to the activation of sodium channels. B, The motor neuron releases the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine at the neuromuscular junction, which then acts on nearby autocrine receptors to trigger a signaling pathway that activates sodium channels. Ine attenuates this signaling by neurotransmitter reuptake. C, The motor neuron releases the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine at the neuromuscular junction, which then acts on receptors present on the neighboring peripheral glia. This interaction increases the release of a factor from peripheral glia that activates axonal sodium channels. Ine attenuates this signaling by neurotransmitter reuptake.

The second mechanism (Fig. 9B) suggests that the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine is released from the motor nerve terminal and acts on autoreceptors on the motor neuron. In this model, Ine could function from either the motor neuron or the peripheral glia to terminate this signaling. As above, binding of the transmitter to its receptors in the motor neuron triggers a signal transduction pathway that activates sodium channels. Sodium channels near the nerve terminal would be the most prominent candidates for this activation. However, the reduced axonal action potential amplitudes observed inOverine+ would require that the signal be transduced from the motor nerve terminal along the length of the axon.

The third mechanism (Fig. 9C) suggests that the substrate neurotransmitter of Ine is released from the motor neuron and activates receptors in the peripheral glia. The activated peripheral glia then release factors that act reciprocally on the motor axon to increase sodium currents, thus forming a positive feedback loop (Fig.9C). It is well documented that neurons release factors that affect adjoining glia and that glia can produce factors that increase neuronal excitability. For example, at the frog neuromuscular junction, motor nerve stimulation or neurotransmitter application increase intracellular [Ca2+] in perisynaptic Schwann cells (Jahromi et al., 1992). Glial also release substances that affect excitability of the neurons (Pfrieger and Barres, 1997) (for review, see Vesce et al., 1999). For example, the Drosophila axotactin (axo) gene encodes a neurexin-related protein that is produced by peripheral glia and subsequently localized to axon tracts (Yuan and Ganetzky, 1999). Mutations in axo cause temperature-sensitive paralysis and failure of compound action potentials at the restrictive temperature (Yuan and Ganetzky, 1999), which are phenotypes exhibited by Overine+larvae as well and presumably result from reductions in axonal sodium currents. The mechanism shown in Figure 9C requires that production or release of this excitability factor from peripheral glia be increased in ine mutants and reduced inOverine+ larvae. Yager et al. (2001)recently proposed that ine mutations increase the release of a factor from peripheral glia that increases the growth of the outer perineurial glial layer. This proposal is consistent with the mechanism proposed here.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM46566 (M.S.). We are grateful to Vanessa Auld, Andrea Brand, Martin Burg, Bill Pak, and the Drosophila stock center in Bloomington, Indiana for supplying fly lines, Martin Burg and Bill Pak for providing DNA clones, Lai Ding for assistance with data analysis, and Mike Gustin for comments on this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Michael Stern, Department of Biochemistry, MS-140, Rice University, P. O. Box 1892, Houston, TX 77251-1892. E-mail: stern@bioc.rice.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso JM, Hirayama T, Roman G, Nourizadeh S, Ecker JR. EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;284:2148–2152. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auld VJ, Fetter RD, Broadie K, Goodman CS. Gliotactin, a novel transmembrane protein on peripheral glia, is required to form the blood-nerve barrier in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;81:757–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann A, Krah-Jentgens I, Mueller R, Muller-Holtkamp F, Seidel R, Kecskemethy N, Casal J, Ferrus A, Pongs O. Molecular organization of the maternal effect region of the Shaker complex of Drosophila: characterization of an IA channel transcript with homology to vertebrate Na+ channel. EMBO J. 1987;6:3419–3429. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brand AH, Manoukian AS, Perrimon N. Ectopic expression in Drosophila. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;44:635–654. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burg MG, Geng C, Guan Y, Koliantz G, Pak WL. Drosophila rosA gene, which when mutant causes aberrant photoreceptor oscillation, encodes a novel neurotransmitter transporter homologue. J Neurogenet. 1996;11:59–79. doi: 10.3109/01677069609107063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chouinard SW, Wilson GF, Schlimgen AK, Ganetzky B. A potassium channel beta subunit related to the aldo-keto reductase superfamily is encoded by the Drosophila hyperkinetic locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6763–6767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng G, Deak P, Chopra M, Hall LM. Cloning and functional analysis of tipE, a novel membrane protein that enhances Drosophila para sodium channel function. Cell. 1995;82:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganetzky B, Wu CF. Drosophila mutants with opposing effects on nerve excitability: genetic and spatial interactions in repetitive firing. J Neurophysiol. 1982;47:501–514. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.47.3.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganetzky B. Genetic studies of membrane excitability in Drosophila: lethal interaction between two temperature-sensitive paralytic mutations. Genetics. 1984;108:897–911. doi: 10.1093/genetics/108.4.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganetzky B. Neurogenetic analysis of Drosophila mutations affecting sodium channels: synergistic effects on viability and nerve conduction in double mutants involving tip-E. J Neurogenet. 1986;3:19–31. doi: 10.3109/01677068609106892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganetzky B, Wu CF. Neurogenetics of membrane excitability in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:13–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gho M, McDonald K, Ganetzky B, Saxton WM. Effects of kinesin mutations on neuronal functions. Science. 1992;258:313–316. doi: 10.1126/science.1384131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giese KP, Fedorov NB, Filipkowski RK, Silva AJ. Autophosphorylation at Thr286 of the alpha calcium-calmodulin kinase II in LTP and learning. Science. 1998;279:870–873. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidalgo A, Urban J, Brand AH. Targeted ablation of glia disrupts axon tract formation in the Drosophila CNS. Development. 1995;121:3703–3712. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hille B. Modulation of ion-channel function by G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang X, Huang Y, Chinnappan R, Bocchini C, Gustin MC, Stern M (2002) The Drosophila inebriated-encoded neurotransmitter transporter: dual roles in the control of neuronal excitability and the osmotic stress response. Genetics, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Hurd DD, Saxton WM. Kinesin mutations cause motor neuron disease phenotypes by disrupting fast axonal transport in Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;144:1075–1085. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.3.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson FR, Wilson SD, Strichartz GR, Hall LM. Two types of mutants affecting voltage-sensitive sodium channels in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 1984;308:189–191. doi: 10.1038/308189a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jahromi BS, Robitaille R, Charlton MP. Transmitter release increases intracellular calcium in perisynaptic Schwann cells in situ. Neuron. 1992;8:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90128-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jan LY, Jan YN. Properties of the larval neuromuscular junction in Drosophila melanogaster. J Physiol (Lond) 1976;262:189–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jan YN, Jan LY. Genetic dissection of short-term and long-term facilitation at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:515–519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jan YN, Jan LY, Dennis MJ. Two mutations of synaptic transmission in Drosophila. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1977;198:87–108. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1977.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamb A, Iverson LE, Tanouye MA. Molecular characterization of Shaker, a Drosophila gene that encodes a potassium channel. Cell. 1987;50:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kandel E, Abel T. Neuropeptides, adenylyl cyclase, and memory storage. Science. 1995;268:825–826. doi: 10.1126/science.7754367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kandel ER, Schwartz JH. Molecular biology of learning: modulation of transmitter release. Science. 1982;218:433–443. doi: 10.1126/science.6289442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan WD, Trout W E. The behavior of four neurological mutants of Drosophila. Genetics. 1969;61:399–409. doi: 10.1093/genetics/61.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kernan MJ, Kuroda MI, Kreber R, Baker BS, Ganetzky B. napts, a mutation affecting sodium channel activity in Drosophila, is an allele of mle, a regulator of X chromosome transcription. Cell. 1991;66:949–959. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90440-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulkarni SJ, Padhye A. Temperature sensitive paralytic mutations on the 2nd and 3rd chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Res. 1982;40:191–200. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loughney K, Kreber R, Ganetzky B. Molecular analysis of the para locus, a sodium channel gene in Drosophila. Cell. 1989;58:1143–1154. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallart A, Angaut-Petit D, Bourret-Poulain C, Ferrus A. Nerve terminal excitability and neuromuscular transmission in T(X;Y)V7 and Shaker mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurogenet. 1991;7:75–84. doi: 10.3109/01677069109066212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Dowd DK, Aldrich RW. Voltage-clamp analysis of sodium channels in wild-type and mutant Drosophila neurons. J Neurosci. 1988;8:3633–3643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-10-03633.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papazian DM, Schwarz TL, Tempel BL, Jan YN, Jan LY. Cloning of genomic and complementary DNA from Shaker, a putative potassium channel gene from Drosophila. Science. 1987;237:749–753. doi: 10.1126/science.2441470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfrieger FW, Barres BA. Synaptic efficacy enhanced by glial cells in vitro. Science. 1997;277:1684–1687. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poulain C, Ferrus A, Mallart A. Modulation of type A K+ current in Drosophila larval muscle by internal Ca2+; effects of the overexpression of frequenin. Pflügers Arch. 1994;427:71–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00585944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sepp KJ, Auld VJ. Conversion of lacZ enhancer trap lines to GAL4 lines using targeted transposition in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1999;151:1093–1101. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.3.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siddiqi O, Benzer S. Neurophysiological defects in temperature-sensitive paralytic mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3253–3257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.9.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soehnge H, Huang X, Becker M, Whitley P, Conover D, Stern M. A neurotransmitter transporter encoded by the Drosophila inebriated gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13262–13267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spradling A. P element-mediated transformation. In: Roberts DB, editor. Drosophila—a practical approach. IRL; Washington, DC: 1986. pp. 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stern M, Ganetzky B. Altered synaptic transmission in Drosophila Hyperkinetic mutants. J Neurogenet. 1989;5:215–228. doi: 10.3109/01677068909066209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stern M, Ganetzky B. Identification and characterization of inebriated, a gene affecting neuronal excitability in Drosophila. J Neurogenet. 1992;8:157–172. doi: 10.3109/01677069209083445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stern M, Kreber R, Ganetzky B. Dosage effects of a Drosophila sodium channel gene on behavior and axonal excitability. Genetics. 1990;124:133–143. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki DT, Grigliatti T, Williamson R. Temperature-sensitive mutations in Drosophila melanogaster. VII. A mutation (para-ts) causing reversible adult paralysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:890–893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.5.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tempel BL, Papazian DM, Schwarz TL, Jan YN, Jan LY. Sequence of a probable potassium channel component encoded at Shaker locus of Drosophila. Science. 1987;237:770–775. doi: 10.1126/science.2441471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vesce S, Bezzi P, Volterra A. The highly integrated dialogue between neurons and astrocytes in brain function. Sci Prog. 1999;82:251–270. doi: 10.1177/003685049908200304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Renger JJ, Griffith LC, Greenspan RJ, Wu CF. Concomitant alterations of physiological and developmental plasticity in Drosophila CaM kinase II-inhibited synapses. Neuron. 1994;13:1373–1384. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warmke J, Drysdale R, Ganetzky B. A distinct potassium channel polypeptide encoded by the Drosophila eag locus. Science. 1991;252:1560–1562. doi: 10.1126/science.1840699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wickman KD, Clapham DE. G-protein regulation of ion channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:278–285. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu C-F, Ganetzky B. Genetic alteration of nerve membrane excitability in temperature sensitive paralytic mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 1980;286:814–816. doi: 10.1038/286814a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu C-F, Ganetzky B. Neurogenetic studies of ion channels in Drosophila. Ion Channels. 1992;3:261–314. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3328-3_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu C-F, Wong F. Frequency characteristics in the visual system of Drosophila: genetic dissection of electroretinogram components. J Gen Physiol. 1977;69:705–724. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.6.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu C-F, Ganetzky B, Jan LY, Jan YN. A Drosophila mutant with a temperature-sensitive block in nerve conduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4047–4051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yager J, Richards S, Hekmat-Scafe DS, Hurd DD, Sundaresan V, Caprette DR, Saxton WM, Carlson JR, Stern M. Control of Drosophila perineurial glial growth by interacting neurotransmitter-mediated signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10445–10450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191107698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan LL, Ganetzky B. A glial-neuronal signaling pathway revealed by mutations in a neurexin-related protein. Science. 1999;283:1343–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5406.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhong Y, Wu CF. Alteration of four identified K+ currents in Drosophila muscle by mutations in eag. Science. 1991;252:1562–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.2047864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]