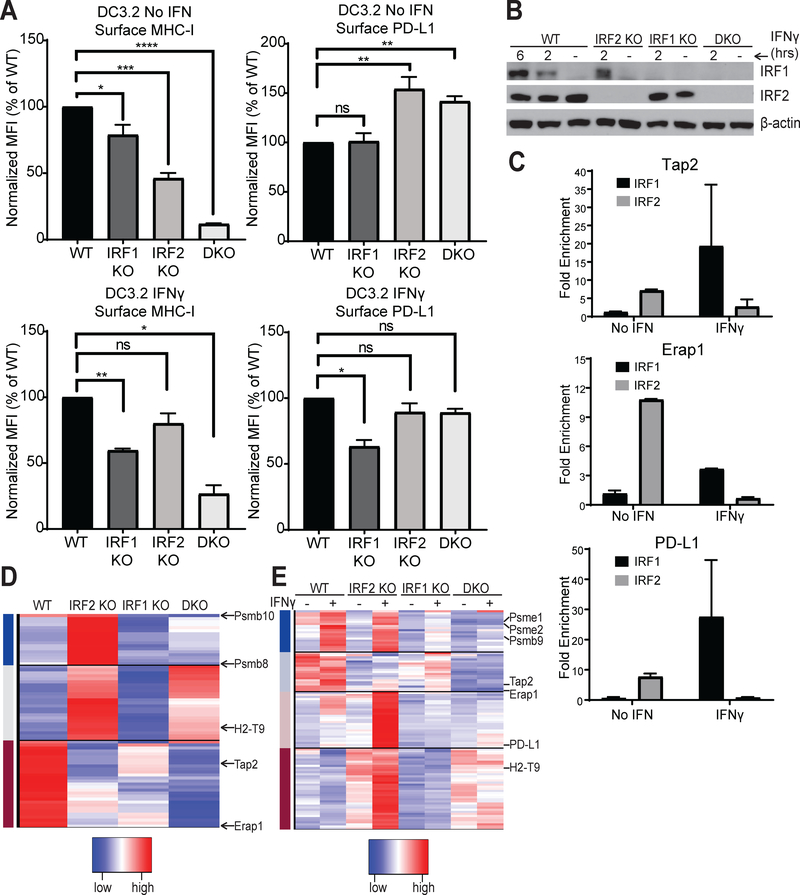

Figure 5. Contributions of IRF1 vs. IRF2.

(A) Normalized MFI of surface MHC I and PD-L1 levels on the indicated single or double (IRF1+IRF2, DKO) DC3.2 knockout lines after overnight incubation with either media alone or 2ng/mL IFNγ; bars represent mean + SEM (N≥3); (B) Western blot for IRF1 and IRF2 (and β-actin as loading control) in the DC3.2 knockout lines in the absence or presence of 2ng/mL IFNγ for the durations indicated; (C) ChIP-qPCR of DC3.2 WT cells stimulated with ± 2ng/mL IFNγ for two hours for Tap2 (top), Erap1 (middle), or PD-L1 (bottom) DNA with rabbit anti-IRF2 IgG, rabbit anti-IRF1 IgG, or normal rabbit IgG (control). Bars represent mean + SEM fold enrichment (2^-ΔCt) over the normal rabbit IgG control IP (N=2); (D, E) Heatmap of genes differentially expressed between the DC knockout lines (D) at baseline or (E) after stimulation with ± 2ng/mL IFNγ for 2hrs. For clarity, only a few genes are shown, and all are listed in Table S1. Statistical analysis by two-tailed ratio paired t-tests. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ns=not significant.