Abstract

In this work, we report an analysis of the draft genome of the blueberry (Vaccinium spp. var. Biloxi) growth-promoting endophyte Bacillus toyonensis, strain COPE52. The genome of COPE52 consists of a single 5,806,513 bp replicon, with a 35.1% G + C content. Strain COPE52 was strongly affiliated to B. toyonensis species, based on species delimitation cut-off values established for average nucleotide identity (> 95–96%), genome-to genome distance calculator (> 70%) and phylogenomic analysis. The RAST genomic annotation of the COPE52 strain revealed a total of 5979 total genes, including 5631 protein-coding genes, 11 rRNA genes, 5 ncRNAs, 81 tRNA genes, and 251 pseudogenes. To further validate the in silico analysis results, experiments were carried out to detect the production of indoleacetic acid, protease activity, and the emission of volatiles like acetoin, 2,3-butanediol and dimethyl disulphide as potential plant growth-promoting mechanisms. COPE52 also showed antifungal action against the grey mould phytopathogen, Botrytis cinerea, during in vitro bioassays. In addition, inoculation with strain COPE52 promoted growth biomass and chlorophyll content in blueberry plants (Vaccinium spp. var. Biloxi) under greenhouse conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing genomic and experimental evidence of B. toyonensis as plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-019-1911-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Plant growth-promoting bacteria, Endophytic bacteria, Antifungal activity, Volatiles, Greenhouse

Introduction

Species of the genus Bacillus are widely used as biocontrol agents, biofertilizers, and biostimulants in agriculture (Ruzzi and Aroca 2015; Villarreal-Delgado et al. 2018). B. thuringiensis was among the first biocides to be used in agricultural crops for its insecticidal properties (Bravo et al. 2011). Likewise, B. subtilis is another species that has been characterized as the main agent of commercial biofungicides and biostimulants of plant development (Pérez-García et al. 2011; Xie et al. 2009). The mechanisms of plant protection or stimulation used by the Bacilli can be diverse (direct and indirect), and include the production of bacteriocins, Cry toxins, chitinases, lipases, lipopeptides, siderophores, and other multiple diffusible and volatile compounds (Santoyo et al. 2012; Ryu et al. 2003). Additionally, Bacilli commonly produce the enzyme 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase, which induce plant growth under different types of stress, by reducing ethylene levels (Gamalero and Glick 2015).

Bacillus toyonensis was recently proposed as a new species belonging to the group of B. cereus, although it had previously been studied as a probiotic due to its production of toyocerin, which improves intestinal microbiota and nutrition in animals (Jadamus et al. 2002; Jiménez et al. 2013). However, studies on the putative beneficial roles of B. toyonesis in plants are few as far as we know. For example, strain BAC3151 (previously characterized as B. thuringiensis), isolated from leaves of common bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris), showed antagonistic activity against phytopathogenic bacteria during a pre-screening test (Lopes et al. 2015). Also, in silico analysis of B. toyonensis BAC315 revealed genes associated to the synthesis of antimicrobial compounds, including bacteriocins, non-ribosomal peptides, and chitinases, among others (Lopes et al. 2017). In another recent work, bacterial endophytes were isolated from the medicinal plant Lavandula dentata L., among which, several strains were identified as B. cereus biovar Toyoi, which could belong to the B. toyonensis species, but this was not corroborated. These strains showed production of siderophores, indoleacetic acid (IAA), NH3, and hydrocyanic acid (HCN) and lytic activities (Pereira et al. 2016). However, these previous studies only show the potential benefits of the strains and lack experimental evidence of biocontrol and induction of plant growth.

In this work, we present the draft genome of the endophyte Bacillus toyonensis strain COPE52, as well as in vitro antifungal bioassays against Botrytis cinerea and greenhouse experiments that demonstrate its capacity as a blueberry plant (Vaccinium spp., Var. Biloxi) growth-promoting bacterium. The COPE 52 strain was previously selected from a screening searching for plant growth-promoting endophytic bacteria isolated from Rubus fruticosus roots (Contreras et al. 2016). Additionally, the production of diffusible and volatile compounds was also corroborated experimentally (Santoyo et al. 2019). As far as we know, this is the first work confirming the B. toyonensis species as a plant growth-promoting bacterium (PGPB).

A single colony of the strain B. toyonensis COPE52 was inoculated on 50 ml of Nutrient Broth (NB), and grown overnight at 28 °C with agitation at 250 rpm. From the culture, the genomic DNA was extracted using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit according to the manufacturer’s (Promega) instructions. The quality and quantity of the final DNA sample were evaluated via agarose–TAE gel (1.5%) electrophoresis, and using a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), respectively. Genomic samples were sequenced, using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Mr. DNA, Texas, USA) with a coverage of 64.0×. The quality control of the reads was conducted with a FastQC analysis version 0.11.5 (Andrews 2010). Trimmomatic version 0.32 (Bolger et al. 2014) was used to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases. De novo assembly was performed using SPAdes version 3.10.1 (Bankevich et al. 2012) and the “-careful” parameter for reads error correction. The assembled contigs were aligned by Mauve contig Mover (MCM) (Rissman et al. 2009), using the reference genome Bacillus toyonensis BCT-7112 (NCBI project accession: CP006863.1). Additionally, PLACNETw revealed the absence of plasmids in the COPE52 genome (Vielva et al. 2017). The draft genome of COPE52 consists of a single 5,806,513-bp chromosome, with 35.1% G + C content, 5979 total genes, 5631 protein-coding genes, 5 ncRNAs, 11 rRNA genes, 81 tRNA genes, and 251 pseudogenes.

For taxonomic assignment of strain COPE52, its 16S rRNA gene sequence was first used as a blast homology search template in the GenBank databases, revealing high identity with the B. thuringiensis strain ATCC 10792 (99.93%), B. mobilis AH1271 (99.93%), B. toyonensis BCT-7112 (99.86%), and B. pacificus EB422 (99.80%), among others. Then, these Bacilli species [based on the cut-off values on species delimitation established for 16S rRNA (> 98.7%) (Chun et al. 2018)] were compared to COPE52 at the genome level by employing the average nucleotide identity (ANI), using the OrthoANI algorithm (Yoon et al. 2017) and the genome-to-genome distance calculator (GGDC) 2.1 via BLAST (Meier et al. 2013). Based on pre-stablished cut-off values on species delimitation for ANI > 95–96% (Varghese et al. 2015) and GGDC > 70% (Espariz et al. 2016), COPE52 was found to be affiliated to Bacillus toyonensis (Table 1).

Table 1.

ANI and GGDC values obtained from the comparison of strain COPE52 and closely related Bacilli species (16S rRNA > 98.7%) and genome-to genome distance calculator (> 70%)

| Bacillus toyonensis COPE52 vs | Ortho ANI (%) | GGDC (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus toyonensis BCT-7112T | 98.55 | 87.4 |

| Bacillus thuringiensis ATCC 10792T | 91.48 | 44.6 |

| Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579T | 91.41 | 44.3 |

| Bacillus wiedmannii FSL W8-0169T | 91.18 | 43.3 |

| Bacillus luti TD41T | 90.95 | 43 |

| Bacillus tropicus N24 | 90.93 | 42.7 |

| Bacillus mobilis AH1271 | 90.92 | 42.6 |

| Bacillus paranthracis Mn5 | 90.83 | 42.2 |

| Bacillus anthracis Ames | 90.81 | 42.5 |

| Bacillus albus N35-10-2 | 90.8 | 42.3 |

| Bacillus pacificus EB422 | 90.72 | 41.9 |

| Bacillus proteolyticus TD42 | 90.61 | 40.1 |

| Bacillus nitratireducens 4049 | 90.41 | 41.4 |

| Bacillus mycoides ATCC 6462 | 90.23 | 40.9 |

| Bacillus paramycoides NH24A2 | 89.65 | 38.9 |

| Bacillus gaemokensis KCTC 13318 | 82.84 | 26.6 |

| Bacillus bingmayongensis FJAT-13831 | 82.81 | 27.3 |

| Bacillus pseudomycoides DSM 12442 | 82.54 | 27.2 |

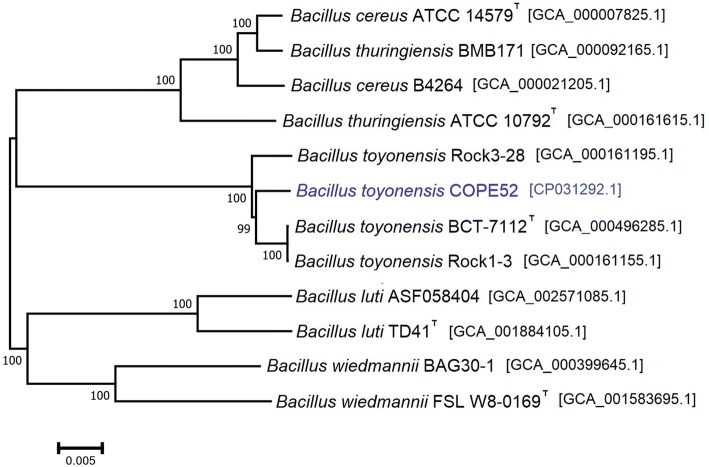

Phylogenomic analysis of B. toyonensis and other Bacilli also corroborated a close relationship within a single clade with B. toyonensis BCT-7112T, B. toyonensis Rock1-3, and B. toyonensis Rock3-28, which were grouped apart from B. cereus ATCC 14579T, B. cereus B4264, B. thuringiensis ATCC 10792T, B. thuringiensis BMB171, B. luti AFS058404, B. luti TD41T, B. wiedmannii BAG30-1, and B. wiedmannii FSL W8-0169T. Genomic sequences were aligned by the reference sequence alignment-based phylogeny builder method, REALPHY (Bertels et al. 2014,) and the genome-based phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA 7 (Kumar et al. 2016), using the Neighbor-Joining method, with a bootstrap support of 1000 replications (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships among strain COPE52 and its closely related Bacillus species: B. toyonensis BCT-7112T (GCA_000496285.1), B. toyonensis Rock1-3 (GCA_000161155.1), B. toyonensis Rock3-28 (GCA_000161195.1), B. cereus ATCC 14579T (GCA_000007825.1), B. cereus B4264 (GCA_000021205.1), B. thuringiensis ATCC 10792T (GCA_000161615.1), B. thuringiensis BMB171 (GCA_000092165.1), B. luti AFS058404 (GCA_002571085.1), B. luti TD41T (GCA_001884105.1), B. wiedmannii BAG30-1 (GCA_000399645.1) and B. wiedmannii FSL W8-0169T (GCA_001583695.1). The Bacillus genomic sequences were aligned using REALPHY (Bertels et al. 2014) and the genome-based phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA 7 (Kumar et al. 2016), using the Neighbor-Joining method, with bootstrap support of 1000 replications

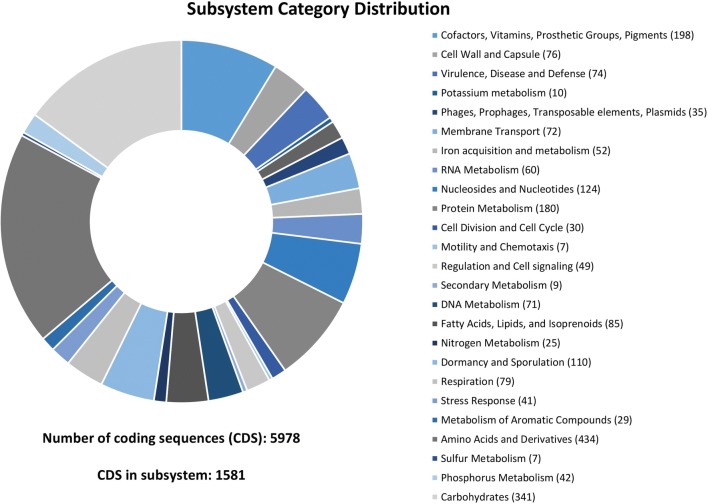

Gene annotation of strain COPE52 was carried out using the Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) server (http://rast.nmpdr.org) (Aziz et al. 2008), by the RASTtk pipeline. A total of 5631 protein-coding DNA sequences (CDSs) were assigned to 358 subsystems, the most abundant being Amino Acids and Derivates (434), Carbohydrates (341), Cofactors, Vitamins, Prosthetic Groups, Pigments (198), Protein Metabolism (180), Nucleosides and Nucleotides (124), and Dormancy and Sporulation (110). Among those relevant for antagonism, rhizo- and endospheric colonization, the genes involved in virulence, disease and defence (74), stress response (41), motility and chemotaxis (7), iron (52), phosphorous (42) and sulphur (7) metabolism are worth mentioning (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Subsystem category distribution of CDC from the Bacillus toyonensis strain COPE52

The strain COPE52 was experimentally evaluated to detect direct and indirect (antifungal effects) plant growth-promoting traits (Santoyo et al. 2019). COPE52 was able to produce IAA (24.08 ± 0.50 µg/mL) and protease activity (28.6 ± 1.6, measured as a halo diameter in skim milk medium), but siderophore production, ACC deaminase activity, and phosphate solubilization were not detected. However, COPE52 restricted mycelial growth of Botrytis cinerea by diffusible (11.49 ± 0.84% decrease in mycelium diameter) and volatile (36.41 ± 2.3% decrease in mycelium diameter) organic compound (VOC) emission (Supplementary Table 1). Since B. toyonensis COPE52 exhibited better antagonism through VOCs against the phytopathogen, compared with B. cinerea, the VOCs produced by the studied endophyte were analysed using SPME–GC–MS, as previously reported (Hernández-León et al. 2015). Supplementary Table 2 shows the cocktail of VOCs produced by COPE52, highlighting the production of acetoin and 2,3-butanediol, which induce systemic resistance and growth in Arabidopsis (Ryu et al. 2003; Rudrappa et al. 2010), and dimethyl disulphide, which has been associated with antifungal action in PGPB (Rojas-Solís et al. 2018). It is relevant to mention that the B. cinerea commonly affects berries around the world, including blueberry plants (Rosslenbroich and Stuebler 2000).

To further confirm the role of B. toyonensis COPE52 as a PGPB, greenhouse experiments were performed in sterile peat moss to evaluate growth promotion in blueberry (var. Biloxi) plants, exerted by COPE52. The experimental design included two treatments: control (n = 88) plants without inoculant and plants inoculated with COPE52 (n = 88), with a total of 166 experimental units. The first bacterial inoculum was applied after 1 week of pot transplantation, in total four inoculations were applied to plants. Control plants were irrigated with sterile deionized water. Bacterial inoculum was adjusted to 1 × 108 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/mL. Throughout the experiment, the plants were irrigated every third day with sterile deionized water. The effect of adding COPE52 on the root length, aerial parts, fresh and dry weight, and chlorophyll concentration was evaluated after 20 weeks of plant growth. The chlorophyll concentration was measured in at least three leaves from each plant as previously reported (Rojas-Solís et al. 2018). Thus, the inoculation of B. toyonensis COPE52 resulted in a growth stimulation of blueberry plants, compared to un-inoculated plants. Except for the measurement of root length, COPE52 induced a significant (p = 0.05) shoot length, fresh and dry weight of shoots and roots, and chlorophyll content (Table 2).

Table 2.

Blueberry plants (var. Biloxi) growth promotion by the inoculation of Bacillus toyonensis COPE52 in greenhouse assay

| Variables | Control | Bacillus toyonensis COPE52 |

|---|---|---|

| Shoot length (cm) | 23.8 ± 0.97 | 29.4 ± 0.50* |

| Root lenght (cm) | 12.0 ± 0.52 | 13.4 ± 0.35 |

| Chlorophil content (U) | 13.3 ± 1.81 | 26.0 ± 2.21* |

| Fresh weight of shoot (g) | 2.5 ± 0.28 | 3.8 ± 0.14* |

| Dry weight of shoot (g) | 0.7 ± 0.07 | 1.1 ± 0.03* |

| Fresh weight of root (g) | 0.3 ± 0.07 | 2.1 ± 0.18* |

| Dry weight of root (g) | 0.2 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.03* |

Values shown are the mean of ten independent replicates with ± standard errors values. Asterisks indicate significant differences according to t Student test (p ≤ 0.05)

In conclusion, our results confirm the function of predicted genes in the genome of COPE52, as well as the diverse plant growth-promoting traits exhibited by this strain. To our knowledge, this is the first work that demonstrates genomic and experimental evidences of Bacillus toyonensis as antifungal and plant growth-promoting bacterium.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Lourdes Macías for her help with the VOCs analysis. We thank to Coordinación de la Investigación Científica-UMSNH for supporting our research projects (2018–2019) and to CONACYT-México (Project: A1-S-15956). M.C.-P. received a PhD scholarship from CONACYT-México.

Accession numbers

This Whole Genome Shotgun sequence project has been deposited to GenBank under the accession number, CP031292.1. The BioSample (SAMN09462204) and BioProject (PRJNA476959) numbers are also available.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andrews S (2010) FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc. Accessed 31 Jan 2019

- Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best A, et al. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008;9:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertels F, Silander OK, Pachkov M, Rainey PB, Van Nimwegen E. Automated reconstruction of whole-genome phylogenies from short-sequence reads. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:1077–1088. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo A, Likitvivatanavong S, Gill SS, Soberón M. Bacillus thuringiensis: a story of a successful bioinsecticide. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;41:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J, Oren A, Ventosa A, et al. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:461–466. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras M, Loeza PD, Villegas J, Farias R, Santoyo G. A glimpse of the endophytic bacterial diversity in roots of blackberry plants (Rubus fruticosus) Genet Mol Res. 2016;15:1–10. doi: 10.4238/gmr.15038542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espariz M, Zuljan FA, Esteban L, Magni C. Taxonomic identity resolution of highly phylogenetically related strains and selection of phylogenetic markers by using genome-scale methods: the Bacillus pumilus group case. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamalero E, Glick BR. Bacterial modulation of plant ethylene levels. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:13–22. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-León R, Rojas-Solís D, Contreras-Pérez M, del Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda M, Macías-Rodríguez LI, Reyes-de la Cruz H, Valencia-Cantero E, Santoyo G. Characterization of the antifungal and plant growth-promoting effects of diffusible and volatile organic compounds produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens strains. Biol Control. 2015;81:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2014.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jadamus A, Vahjen W, Schäfer K, Simon O. Influence of the probiotic strain Bacillus cereus var. toyoi on the development of enterobacterial growth and on selected parameters of bacterial metabolism in digesta samples of piglets. Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2002;86:42–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0396.2002.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez G, Urdiain M, Cifuentes A, López-López A, Blanch AR, Tamames J, Kämpfer P, Kolstø AB, Ramón D, Martínez JF, Codoñer FM, Rosselló-Móra R. Description of Bacillus toyonensis sp. nov., a novel species of the Bacillus cereus group, and pairwise genome comparisons of the species of the group by means of ANI calculations. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2013;36:383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes RBM, de Oliveira Costa LE, Vanetti MCD, de Araújo EF, de Queiroz MV. Endophytic bacteria isolated from common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) exhibiting high variability showed antimicrobial activity and quorum sensing inhibition. Curr Microbiol. 2015;71:509–516. doi: 10.1007/s00284-015-0879-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes R, Cerdeira L, Tavares GS, Ruiz JC, Blom J, Horácio ECA, Mantovani HC, Queiroz MV. Genome analysis reveals insights of the endophytic Bacillus toyonensis BAC3151 as a potentially novel agent for biocontrol of plant pathogens. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;33:185. doi: 10.1007/s11274-017-2347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier J, Auch A, Klenk H, Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira SIA, Monteiro C, Vega AL, Castro PM. Endophytic culturable bacteria colonizing Lavandula dentata L. plants: isolation, characterization and evaluation of their plant growth-promoting activities. Ecol Eng. 2016;87:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.11.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García A, Romero D, de Vicente A. Plant protection and growth stimulation by microorganisms: biotechnological applications of Bacilli in agriculture. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman AI, Mau B, Biehl BS, Darling AE, Glasner JD, Perna NT. Reordering contigs of draft genomes using the Mauve aligner. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2071–2073. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Solís D, Zetter-Salmón E, Contreras-Pérez M, Rocha-Granados M, Macías-Rodríguez L, Santoyo G. Pseudomonas stutzeri E25 and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia CR22 endophytes produce antifungal volatile organic compounds and exhibit additive plant growth-promoting effects. Biocat Agric Biotech. 2018;13:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2017.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosslenbroich HJ, Stuebler D. Botrytis cinerea—history of chemical control and novel fungicides for its management. Crop Protect. 2000;19:557–561. doi: 10.1016/S0261-2194(00)00072-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudrappa T, Biedrzycki ML, Kunjeti SG, Donofrio NM, Czymmek KJ, Paré PW, Bais HP. The rhizobacterial elicitor acetoin induces systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Commun Integr Biol. 2010;3:130–138. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.2.10584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzi M, Aroca R. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria act as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci Hortic. 2015;196:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.08.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu CM, Farag MA, Hu CH, Reddy MS, Wei HX, Paré PW, Kloepper JW. Bacterial volatiles promote growth in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4927–4932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730845100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo G, Orozco-Mosqueda MDC, Govindappa M. Mechanisms of biocontrol and plant growth-promoting activity in soil bacterial species of Bacillus and Pseudomonas: a review. Biocon Sci Technol. 2012;22:855–872. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2012.694413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo G, Sánchez-Yáñez JM, de los Santos-Villalobos S. Methods in rhizosphere biology research. Singapore: Springer; 2019. Methods for detecting biocontrol and plant growth-promoting traits in rhizobacteria; pp. 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Varghese NJ, Mukherjee S, Ivanova N, Konstantinidis KT, Mavrommatis K, Kyrpides NC, Pati A. Microbial species delineation using whole genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6761–6771. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vielva L, de Toro M, Lanza V, de la Cruz F. PLACNETw: a web-based tool for plasmid reconstruction from bacterial genomes. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3796–3798. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal-Delgado M, Villa E, Cira L, Estrada M, Parra F, de los Santos-Villalobos S. The genus Bacillus as a biological control agent and its implications in the agricultural biosecurity. Rev Mex Fitopatol. 2018;36:95–130. doi: 10.18781/R.MEX.FIT.1706-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Zhang H, Paré PW. Sustained growth promotion in Arabidopsis with long-term exposure to the beneficial soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis (GB03) Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4:948–953. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.10.9709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SH, Ha SM, Kwon S, Lim J, Kim Y, Seo H, Chun J. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:1613–1617. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.