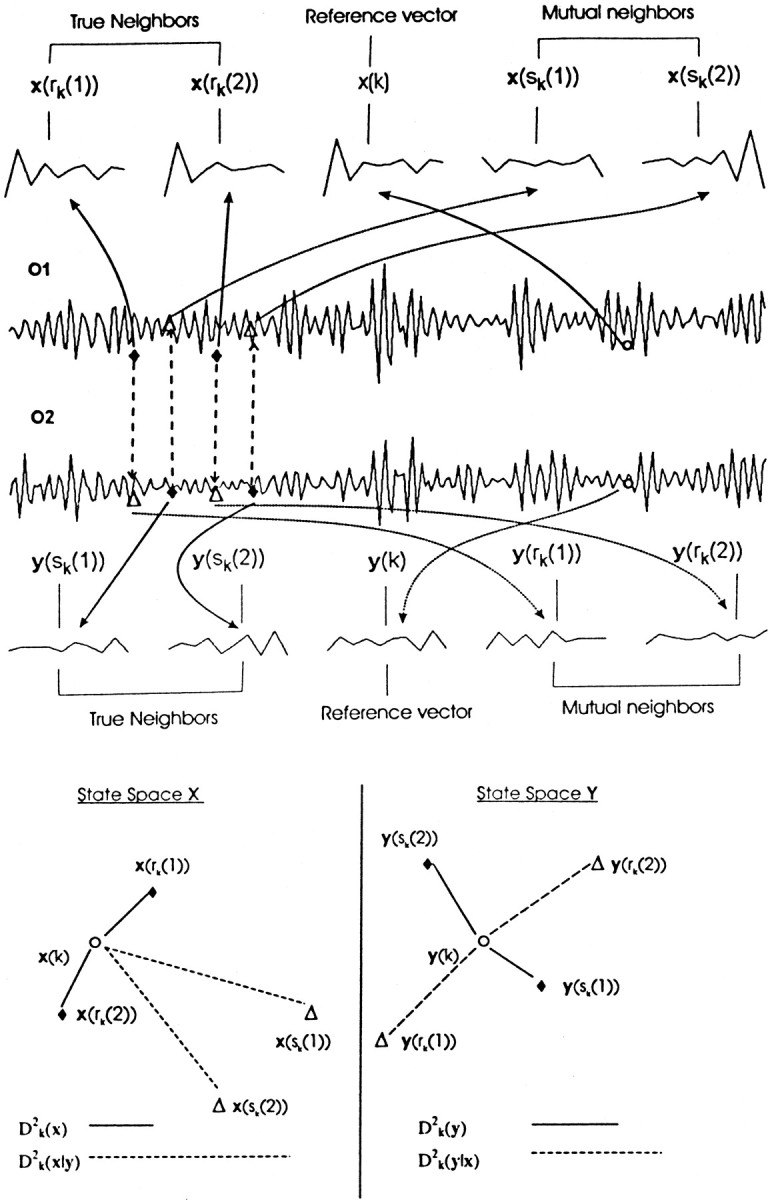

Fig. 2.

Top, Pictorial descriptions of true and mutual neighbors. Two simultaneous EEG epochs filtered in the γ band (1.8 sec each) of two channels (O1 and O2 represented by system x and y, respectively) for a musician while listening to music. For a reference vector (o), the nearest or true neighbors (filled diamonds) and mutual neighbors (open triangles) are shown. For the sake of clarity only two vectors (r = 2 in Eq. 3and 4) are used. For the reference vector x(k), its nearest neighbors are x(rk(1)) and x(rk(2)), whereas for the simultaneous reference vector y(k), its two true neighbors (filled diamonds) are y(sk(1)) and y(sk(2)). The mutual neighbors of x(k) are those vectors x(sk(1)) and x(sk(2)) (open triangles) simultaneous to the nearest neighbors of y(k), which consequently bear the same time indices. In an analogous way, the mutual neighbors of y(k) are y(rk(1)) and y(rk(2)). All these vectors are shown with the reconstruction parameters m = 10 andτ = 2. Bottom, The reconstructed state spaces of X and Y, in which both the actual (solid lines) and conditional (dashed lines) distances are displayed for comparison. Similarity index S (Eq. 5) for x(k) is simply the ratio between both distances. In the top half, note that the pattern for x(k) is similar to that of its nearest neighbors but does not match that of its mutual neighbors; this fact is more prominent in distance measures. For this chosen example,D2k(x‖y) >D2k(y‖x) which leads toS(Y‖X) > S(X‖Y), i.e., X has more influence on Y than vice versa. We would like to emphasize that this index has to be calculated for all possible reference vectors and finally averaged to get the final value of similarity index.