Abstract

Spatiotemporal patterns of morphogen activity drive differential gene expression with a high degree of precision within a developing embryo and reproducibly between embryos. Understanding the formation and function of a morphogen gradient during development requires quantitative measurement of morphogen activity throughout an individual embryo and also between embryos within a population. Quantification of morphogen gradients in to presents unique challenges in imaging and image processing to minimize error and maximize the quality of the data so it may be used in computational models of development and in statistically testing hypotheses. Here we present methods for the preparation, immunostaining, imaging, and quantification of a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) activity gradient in individual zebrafish embryos as well as methods for acquiring population-level statistics after embryo grouping and alignment. This quantitative approach can be extended to other morphogen systems, and the computational codes can be adapted to other imaging contexts in zebrafish and other organisms.

Keywords: Morphogen, Gradient, Zebrafish, Quantitative imaging, BMP signaling

1. Introduction

The quantification of morphogen gradient activity through fluorescent imaging has grown increasingly important to studies delineating how gradients form in space and time to drive cellular differentiation during development. In Drosophila, where morphogen gradients form along the anterior-posterior (AP) and dorsalventral (DV) axes, quantification of morphogen gradients by fluorescent methods has provided insight into how gradients form [1–3], how information is transduced from the gradient to regulate gene expression [4, 5], and how feedback between regulatory motifs can drive pattern formation [6, 7].

The approaches for quantifying morphogen gradients or their activity in zebrafish share many similarities to those used in Drosophila morphogen gradients. Morphogens in Drosophila can be visualized directly by in situ methods detecting endogenous proteins, live imaging of fluorescent fusion proteins, or antibody staining of epitope-tagged proteins. These approaches have proven effective for quantifying the AP gradient of the Bicoid (Bcd) transcription factor and the DV gradient of nuclear Dorsal (Dl) in Drosophila [6, 8].

In the zebrafish embryo, nodal and retinoic acid (RA) morphogen gradients have also been quantified; nodal signaling activity induces mesendoderm along the animal-vegetal (AV) axis, and RA patterns tissues along the AP axis (reviewed in [9]). Nodal signaling results in the phosphorylation of Smad2, which subsequently accumulates in the nucleus. Multiple methods have leveraged nuclear Smad2 to quantify nodal signaling activity by measuring nuclear Venus-Smad2 intensity, bimolecular fluorescent complementation of Venus between Smad2 and Smad4, and the nucleocytoplasmic ratio of GFP-Smad2 [10–12]. Further, levels of nuclear Smad2 and the distributions of the GFP-Smad2 nucleocytoplasmic ratio have both been related to the expression of nodal direct targets [10, 11]. Additional measurements in the zebrafish embryo include phosphorylated Smad2 levels along the AV axis [13] and nodal-GFP fusion proteins emanating in a gradient from transplants that express nodal-GFP [11]. Finally, the RA gradient has been quantified through the development of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) probes [14] and, more recently, by using fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) and relying on the inherent fluorescence of RA [15].

However, in both Drosophila and zebrafish, the gradient of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling that directs DV patterning is not easily measured by in situ or fusion protein approaches. While there has been some success in Drosophila visualizing Dpp (Drosophila BM P2/4 homologue) through a Dpp-GFP fusion protein and an HA epitope-tagged Dpp, neither approach was sufficient for quantification [8, 16]. Instead, quantification of the BMP signaling gradient in both Drosophila and zebrafish relies on using an antibody that specifically recognizes the phosphorylated form of Sm ad1/5/8 (P-Smad5 in zebrafish, P-Mad in Drosophila) and the intracellular transcription factor that is directly phosphorylated by BMP receptors and transduces the BMP signal. Though it is difficult to measure Dpp-GFP, a previous study in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc overexpressed Dpp-GFP and established a linear relationship between the level of P-Mad and the level of Dpp-GFP, supporting the use of P-Mad as a direct readout of extracellular BMP in this context [17].

In Drosophila, the earliest quantitative imaging of BMP signaling and computational models of patterning focused on P-Mad dynamics along the DV axis of the blastoderm embryo. Through nuclear division cycle 14 of Drosophila development, the embryo is a syncytium wherein the nuclei are located in a single layer at the embryo periphery and quantification of the gradient relied on measurement of P-Mad levels from extended focus images, where the maximum intensities from the z-sections are extended to a single 2D image of the dorsal half of the embryo [7]. Since these 2D images of the dorsal surface intensity of P-Mad immunostaining proved reliable and the embryo axes are easily identifiable, this methodology was sufficient to quantify differences in P-Mad distribution between wild-type and BMP pathway mutant embryos and develop mathematical models of BMP signaling in Drosophila [7]. Equivalent methods were later used to identify mutant BMP components in Drosophila that increase embryo-to-embryo variability [18].

However, the methods for quantifying P-Mad in Drosophila were not sufficient to quantify BMP patterning in zebrafish for a number of reasons. First, at each stage of zebrafish development, cells are distributed in thick layers, as opposed to a single-layer syncytium, and BMP signals throughout the deep cells. Second, BMP signaling dynamically specifies cell fates along the AP axis [19, 20] coupling the AP and DV axes and thus requiring future studies aimed at modeling 3D spatiotemporal BMP patterns to have 3D data for model testing (reviewed in [9]). Third, acquiring the data IN TOTO gives the most complete view of BMP signaling and enables examination of signaling dynamics in all regions of the embryo. These requirements for high-quality, 3D images of the zebrafish embryo that can be used in quantification introduce new challenges for acquiring data, particularly due to the potential for refractive index (RI) mismatch between cells, media, yolk, immersion oil, and coverslip that all systematically interfere with quantification [21, 22]. RI mismatch systematically introduces error in quantification through signal drop-off with increasing depth, spherical aberration (an issue that increases with the numerical aperture, NA, of the objective), and axial scaling. Furthermore, unlike in Drosophila, the DV axis ofthe zebrafish embryo is not readily identifiable prior to gastrulation, since the embryo morphology and cell densities are largely symmetrical. Thus, new methods were needed for embryo signal quantification, alignment, and registration.

We developed new approaches and tools to quantify BMP signaling activity in all cells of the relatively large zebrafish embryo. First, we established a fluorescent image acquisition method that minimizes imaging artifacts by careful RI matching and embryo clearing. Following image acquisition of fluorescent-antibody stained P-Smad5 embryos, the high-dimensional image data are converted into an array of nuclei positions similar to that done by others [23], where the average channel intensities are calculated for each nucleus position. This dramatically reduces data storage and, subsequently, the time it takes to calculate the model-data fitness. Consider that in acquiring an image stack that is 1024 × 1024 × 100 (x, y, z) pixels, multiplied by the number of channels (N), there are 1.05N × 108 total points. However, we only need to store the spatial position of each nucleus (x, y, z) and the average channel intensity at each nucleus. Effectively, if an embryo has 10,000 cells, then only 10,000 × 3 × N or 3N × 104 points are stored, reducing the file size from 1.05 × 108 to 3 × 104 and resulting in a 3500 × smaller file.

Following the conversion of the image data, individual embryo point clouds of nuclear positions and associated P-Smad5 levels are registered using an adaptation of coherent point drift (CPD), a robust point alignment method that allows for variability in the total number of points, as well as overall size and orientation of the alignment set (a particular embryo) to the reference set (a reference embryo) [24, 25]. Finally, data from individuals and populations can then be extracted for statistical comparison, including measures of gradient shape and embryo-to-embryo variability of P-Smad5 signaling patterns. In the remainder of this paper, we outline the approach to acquire and process the images to quantify the formation of the BMP signaling gradient in zebrafish embryos.

2. Materials

PBS: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1.46 mM KH2PO4.

4% PFA: 9.25% of a 37% PFA (formaldehyde) solution (Sigma 252549), 91.75% PBS by volume.

PBSTrit: 99.9% PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100 by volume.

NCS-PBSTrit: 10% heat-inactivated newborn calf serum, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% dimethyl sulfoxide, 88.9% PBS.

Methanol.

BABB: two parts benzyl benzoate, one part benzyl alcohol mixed fresh just prior to use.

Long coverslip and a 25 mm × 25 mm silicon wafer with a 10 mm diameter circle cut out of the center and a thickness of 0.7 μm (Grace Biolabs 475271).

Nail polish.

Vacuum grease.

P-Smad1/5/9 Rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling Technology #13820) or Histone H3 Mouse Antibody (Active Motif #39763).

Goat Anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen A-21244/5) or Alexa Fluor 546 (Invitrogen A-11030), if the Histone H3 antibody is used.

1:2000 dilution of Sytox Green (Invitrogen S7020). Store diluted Sytox Green at −80°C in small (2–5 μL) aliquots.

3. Methods

3.1. Embryofixation

Collect zebrafish embryos of the desired stage between 1 and 10 h post fertilization in 1.5 mL tubes, with approximately 25 embryos per tube. Remove as much media as possible from each tube and add 1 mL of 4% PFA solution to each.

Place embryos on a rocker for 4 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C.

Wash embryos four times for 30 min on a rocker with 1 mL of PBS or PBSTrit.

3.2. Removal of the Chorion and Yolk

Transfer embryos to a cell culture dish with PBS or PBSTrit using a plastic transfer pipette.

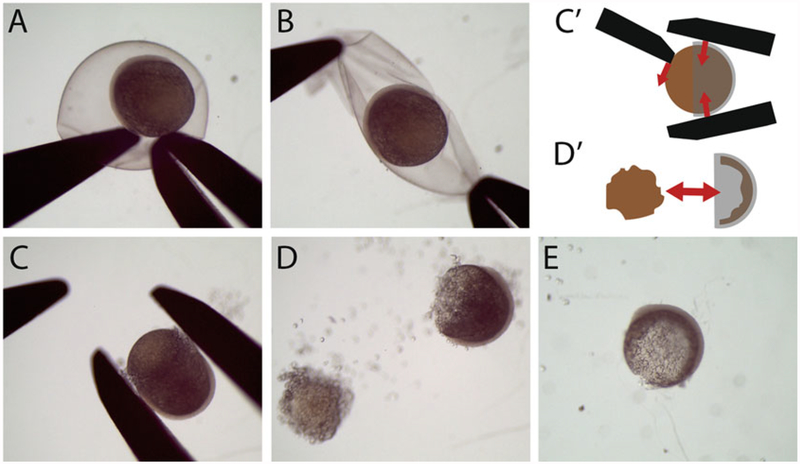

Manually remove the chorion from each embryo under a manual dissecting microscope. Use two microdissection forceps or one micro-dissecting forcep and one dissecting needle (Fig. 1a, b). Do not use proteinase (see Note 1).

Manually remove the yolk. Use forceps to gently squeeze the embryo at its equator while nudging/pulling the yolky vegetal pole away with another pair of forceps or needle (Fig. 1c, cʹ). Part or all of the yolk will separate from the cap of cells (Fig. 1d, dʹ) (see Note 2).

Remove the remaining yolk granules by carefully returning the embryos to the 1.5 mL tube and gently vortexing. This will remove the yolk (Fig. 1e). Since the embryos are delicate, ensure the 1.5 mL tube is filled with no less than 1 mL of liquid to prevent them from sticking to the sides of the tube.

Confirm that the yolk has been fully removed. Carefully return the embryos to the dish of PBS and check that very little yolk is attached to the blastoderm (Fig. 1e).

Return the embryos to anew 1.5 mL tube filled with fresh PBS, leaving the yolk fragments in the dish.

Wash for 5 min with 1 mL of PBSTrit. Embryos can be stored for up to 2 weeks in PBS. Dehydrate in methanol for longer storage.

Fig. 1.

Removing the chorion and yolk from the fixed embryo. (a, b) Chorion removal by grabbing the chorion with forceps while holding another part of the chorion against the dish with a probe (a) and then ripping a hole and pulling the chorion apart to release the embryo (b). (c-e) Removal of the yolk. (c, cʹ) First, gently squeeze the animal cap with forceps while picking at the yolk with a probe. (d, dʹ) Most of the yolk should pop out of the animal cap. (e) The embryo after gentle vortexing, which removes much of the remaining yolk particles

3.3. Fluorescent P-Smad5 Staining

Block embryos in NCS-PBSTrit. Remove PBSTrit and replace with 1 mL of NCS-PBSTrit. Put on a rocker at room temperature for at least 2 h.

- Prepare primary antibody solution. In 0.5 mL NCS-PBSTrit, add:

- 1:200 dilution of P-Smad1/5/9 Rabbit Antibody (Cell Signaling Technology #13820)

- 1:200 dilution of Histone H3 Mouse Antibody (Active Motif #39763) (see Note 3)

Remove NCS-PBSTrit and incubate the embryos with the primary antibody solution on a rocker at 4 °C overnight.

Wash off primary antibody. Remove primary antibody solution and replace with 1 mL PBSTrit. Place on a rocker for 15–30 min and then replace the PBSTrit. Repeat four times.

- Prepare secondary antibody solution. In 0.5 mL of NCS-PBSTrit, add:

- 1:500dilutionofGoatAnti-RabbitAlexaFluor 647 (Invitrogen A-21244/5).

- 1:500 dilution of Goat Anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor 546 (Invitrogen A-11030), if the Histone H3 antibody is used.

- 1:2000 dilution of Sytox Green (Invitrogen S7020) (see Note 4).

Remove PBSTrit and incubate embryos with secondary antibody solution on a rocker in the dark at 4 °C overnight OR at room temperature for at least 2 h. Avoid exposing samples to light for extended periods in all subsequent steps.

Wash off secondary antibody. Remove secondary antibody solution and replace with 1 mL PBSTrit. Place on a rocker for 15–30 min and then replace the PBSTrit. Repeat four times.

Remove as much PBSTrit as possible and replace with 1 mL of PBS. Embryos can be stored in PBS at 4 °C for a few weeks, or they can be dehydrated in methanol for indefinite storage at −20 °C.

3.4. Clearing and Mounting for Imaging

Remove as much PBS as possible and replace with 1 mL of 50% methanol/50% PBS. Let sit for 5 min.

Remove as much 50% methanol/50% PBS as possible and replace with 1 mL of 100% methanol. Let sit for 5 min (see Note 5).

Remove as much methanol as possible and replace with 1 mL of 50% methanol/50% BABB (two parts benzyl benzoate, one part benzyl alcohol). Let sit for 5 min (see Note 6).

Remove as much 50% methanol/50% BABB as possible and replace with 1 mL of 100% BABB. Let sit for 10 min.

Remove as much BABB as possible and replace with 1 mL of 100% BABB. Let sit for 5 min (see Note 7).

-

Method 1 (Fig. 2a–d): Construct an imaging well from a long coverslip and a 25 mm × 25 mm silicon wafer with a 10 mm diameter circle cut out of the center and a thickness of 0.7 μm (Grace Biolabs 475271) (Fig. 2a). Use nail polish to seal the bottom side down to the coverslip; leave the other side open and uncovered (Fig. 2a blue).

Method 2 (Fig. 2e–h): Construct an imaging well from a long coverslip and a ring of silicone vacuum grease (Fig. 2e, f). For easy application, backfill a 1.25 mL plastic syringe with the vacuum grease and carefully push through (see Note 8).

Under a fluorescent dissecting microscope with a green light fluorescent filter, remove a single embryo from the 1.5 mL tube and place it into the imaging well.

Fill the imaging well with BABB until the meniscus is flat across the imaging well (Fig. 2b).

Under the green light of the fluorescent dissecting microscope, adjust the orientation of the embryo. Orient embryos without the yolk (stages prior to 70% epiboly) so that the animal pole is down. Orient embryos with the yolk (stages after 70% epiboly) so that the vegetal pole is down. If the embryo is damaged, discard. Approximately 25% of embryos usually become damaged during the staining and mounting process depending on how gently the washes are performed.

-

Method 1 (Fig. 2a–d): Gently lay another long coverslip on top of the imaging well, laying it down from one side to the other (Fig. 2b), which reduces air bubbles being trapped below the coverslip. Carefully dab the edges of the coverslip with a Kim-wipe to remove any BABB. Dab repeatedly and apply gentle force until very little BABB comes out. Seal the edges with nail polish (Fig. 2c, d) (see Note 9).

Method 2 (Fig. 2e–h): Gently lay a short coverslip, as above, on top of the imaging well and lightly press down to seal (Fig. 2g, h). The short coverslip may be repositioned if necessary.

Image within 8 h, as prolonged time in BABB (~24 h) reduces fluorescence intensity.

Fig. 2.

Mounting the embryo for imaging. A single embryo can be mounted between two coverslips separated by either a silicon wafer (a-d) or silicone vacuum grease (e-h). (a) First, place the silicon wafer onto the coverslip and secure the edges with nail polish (blue), (b) Place the embryo in BABB into the newly formed well, taking care to remove enough BABB so that the meniscus is flat before placing a second coverslip on top. (c, d) After dabbing away excess BABB, seal the edges with nail polish (blue), (e, f) Make a circle of petroleum jelly on a coverslip. (g, h) Place the sample in BABB in the well and seal with a smaller coverslip

3.5. Confocal Imaging

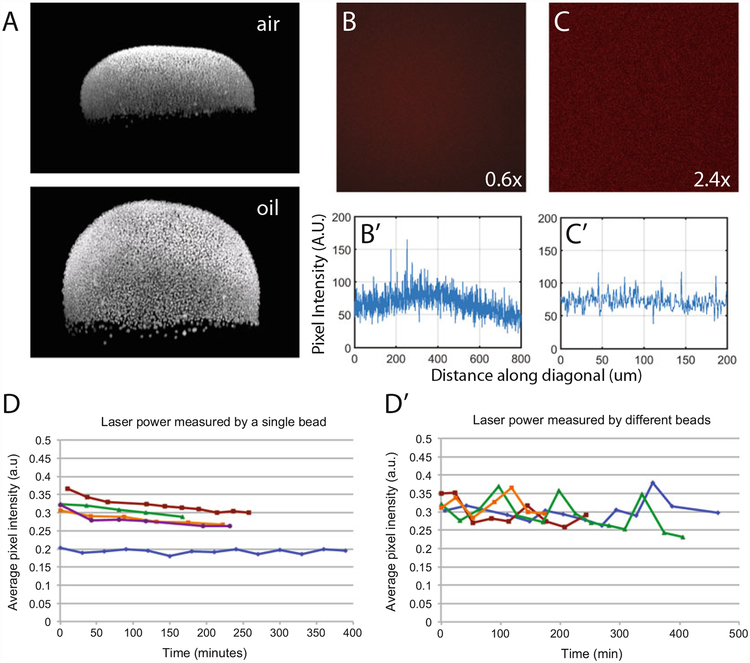

Mount the imaging well on a confocal microscope and image. Calibrate the gain, laser power, and all other settings before imaging the first embryo. Keep all settings the same for the remainder of the set (see Notes 10–15 and Fig. 3).

After imaging, embryos may be recovered from the imaging wells for genotyping. We extracted DNA using the HotShot technique [26] and genotyped single embryos using KASPar [27] or dCAPs genotyping [28] (see Note 16).

Fig. 3.

Controlling for fluorescence artifacts. (a) Lateral max projection of nuclei in the same embryo stained with Sytox Green and imaged using a 20× air lens (top) or a LD LCI Plan-Achromat 25×/0.8 Imm Corr DIC M27 multi-immersion oil lens (bottom). (b, c) Alexa Fluor 647 dissolved in water reveals the nonuniformity across the XYfield in a LD LCI Plan-Achromat 25×/0.8 Imm Corr DIC M27 multi-immersion lens at 0.6× (b) and 2.4× (c) digital zoom. (bʹ, cʹ) Intensity profiles plotted from the top-right to bottom-left corner of the above images revealing a 40% drop-off from the center to the edge at 0.6 × zoom and 8% drop-off from the center to the edge at 2.4× zoom. (d, e) Laser power fluctuation vs. time when imaging a single bead (d) or of different beads (e) on a ThermoFisher cat. no. F369009, well A1 calibration slide

3.6. Nuclei Identification and P-Smad5 Intensity Extraction

We developed a software program to carry out the procedures that are described in the following section. The files and instructions are available for download at: https://elifesciences.org/download/aHR0cHM6Ly9jZG4uZWxpZmVzY2llbmNlcy5vcmcvYXJ0aWNsZXMvMjIxOTkvZWxpZmUtMjIxOTktc3VwcDEtdjIuemlw/elife-22199-supp1-v2.zip?_hash=Zxk8TVpw5NGza2MNi0jq4pD5GuZ%2FVeluqS15rUkVbUo%3D.

The attached link includes the Matlab codes, sample image files, and a brief tutorial to run the software. Here we go into greater depth on the processes and potential modification points for the image analysis codes to meet the requirements of diverse embryo quantification needs.

The first step is completed before starting the MATLAB® script. Convert the “.lsm” confocal stack files to “.tif’ files using ImageJ and then import into Matlab as 1024 × 1024 × Z multidimensional arrays. XƳ pixels are 0.55 μm, Z pixels were 2.2 μm (Fig. 4a).

- Locate the center points of all nuclei using the Histone H3 (or Sytox) stain. This is done by:

- Smoothing the histone H3 (or Sytox) stain with a 3-D Gaussian kernel with a size of approximately 9 pixels (4.95 μm) by 9 pixels (4.95 μm) by 3 pixels (6.9 μm) and a standard deviation of 1.91 (Fig. 4aʹ). This kernel is approximately the size of most nuclei, which are about 6 μm in diameter. To eliminate false positives, remove local minima and maxima H-maxima and H-minima transforms targeting peaks with an intensity less than 10 units (8-bit) higher than background (see Note 17).

- Finding all maxima by using the “imregionalmax” function on the entire 1024 × 1024 × Z array (Fig. 4aʹʹʹ). Maxima closer together than 6 pixels can be assumed to be in the same nucleus and therefore be combined into a single point.

Extract P-Smad5 intensities from the identified nuclei maxima locations (Fig. 4b). P-Smad5 distribution in each nucleus is approximately uniform, so a small sphere within each nucleus is averaged to attain the P-Smad5 intensity. A spherical 6 × 6 × 3 kernel is recommended (see Note 18).

Fig. 4.

Nuclear identification, P-Smad5 measurement, and embryo alignment. (a) Animal view of a single 2.2 μm Z-slice of fluorescently labeled histone H3. (aʹ) The same Z-slice after filtering with a Gaussian kernel 9 pixels (4.95 μm) by 9 pixels (4.95 μm) by 3 pixels (6.9 μm) with a standard deviation of 1.91. (aʹʹ) The number of nuclei identified in a single embryo plotted versus the XY kernel size. (aʹʹʹ) Nuclei with centerpoints on the Z-slice are shown in red, while the Histone H3 stain after all smoothing shown in white. Note that the nuclei that appear to be missed have center points that fall on adjacent planes. Scale bar in a, aʹ, aʹʹʹ is 100 μm. (b) A 3-D display of all nuclei from a single embryo colored by a heatmap of P-Smad5 fluorescence. (c, d) An embryo was imaged, then repositioned, and imaged a second time to determine the overall image acquisition noise, by comparing P-Smad5 fluorescent intensity for each paired nucleus as shown. (c) Correspondence of nuclei for the embryo imaged twice (blue-original image, red-repositioned and reimaged). (d) The overall image acquisition noise includes positioning error and detector noise from the Hamamatsu R6357 photomultiplier tube on a Zeiss 710 confocal. (e) P-Smad5 (red) is absent in cells undergoing mitosis while Sytox Green (green) intensifies (blue arrowheads). (f) Histone H3 intensity vs. P-Smad5 intensity in all nuclei in a single gastrula. Cells with high histone H3 intensity and low P-Smad5 intensity are identified as dividing cells and removed from further analysis

3.7. Embryo Alignment and Processing

- Remove cell types unresponsive to BMP signaling. P-Smad5 is not localized in the nucleus during cell division (Fig. 4e, eʹ), so dividing cells were removed from the analysis.

- Dividing cells are identified by their bright and concentrated Histone H3 (or Sytox) fluorescence. Histone H3 becomes tightly packed when chromatin is condensed during cell division, making DNA stains such as fluorescent Histone H3 or Sytox green bright.

- Cells with a bright DNA fluorescence staining (above 140% of the mean DNA fluorescence) were identified as dividing and eliminated from the analysis (Fig. 4f).

- To calculate population-level statistics for similarities and differences in the mean P-Smad5 levels, embryos of similar stages need to be uniformly aligned along the AV and DV axes.

- Use the software to align the embryos along the DV axis using the embryonic shield as a morphological marker of the dorsal side. We rotate the embryo so that the shield always faces the same direction. Before 6 hpf, when the shield is not present, the embryos can be aligned in the DV direction by fitting a polynomial regression to the P-Smad5 gradient around the margin and rotating until the peak maximum is ventral (Fig. 5c–e).

The shape of some embryos may be altered slightly in the fixation, the antibody staining, or the mounting procedures. To eliminate these imperfections, so that embryos can be compared to each other, we conform embryos to a template embryo using an affine coherent point drift (CPD) (Fig. 5f) [29]. The method aligns the nuclei point clouds as a probability density estimation problem that maximizes the likelihood of correspondence between the nuclei point clouds of the template embryo with the test embryo. The approach maintains the spatial arrangement of the points as a nonrigid point set allowing the point cloud being aligned to “stretch” a small degree to overlap the template [29]. The result of implementing this method is that all embryos are similarly oriented for comparative statistics from the resulting profiles. The template embryo should be an embryo from the dataset that is not deformed. Alignment of the embryos to a template or reference embryo provides a consistent orientation for quantitative comparisons between embryos and for statistically testing hypotheses of the measured gradient properties. The goal of CPD is to fine tune the embryo alignment and also correct for any distortions in embryo shape that may have occurred during fixation and staining (see Notes 19 and 20).

The extraembryonic yolk syncytial layer (YSL) nuclei and the enveloping layer (EVL) cells do not respond to BMP signaling in the same manner as the deep cells. The sparse YSL nuclei located below the vegetal margin were eliminated by hand (Fig. 5g, h). Use the software to remove the remaining YSL nuclei and the EVL cells by removing the inner and outer layer of identified nuclei, approximately 15% of the total nuclei (Fig. 5g, h). The remaining cells were assumed to be nondividing deep cells.

Fig. 5.

Embryo alignment and display. (a, b) The nuclei of an embryo (blue dots) before and after alignment of the AV axis. (c) An animal view of an embryo before rotation to align the DV axis. Nuclei are colored based on their P-Smad5 intensities. (d) A polynomial curve (red line) fit to the nuclei around the margin of the embryo (blue crosses). (e) An animal view of an embryo after rotation to align the DV axis. (f) An embryo (blue dots) after being fit to a reference embryo (red dots) using coherent point drift. (g, h) Lateral view of an embryo before and after the removal of the YSL and EVL nuclei by a MATLAB program. (i) Animal view of the average intensities of 13 WT embryos at 5.7 hpf averaged onto a 1280 sided polyhedron. (j) A band of cells around the margin of the embryo. (k) The average intensity of P-Smad5 in 13 WT embryos around the margin of the embryo

3.8. Displaying the Data

The individual nuclei are then displayed in 3-D in MATLAB using the XƳZ coordinates and associated P-Smad5 intensities (Fig. 5c, e, g, and h).

One useful method for data visualization is to project the average P-Smad5 values from individuals or populations to a 3D mesh representing the zebrafish embryo. The nuclei across multiple embryos are averaged together and projected onto a polyhedron with many sides (4800 in this case). The diameter of the polyhedron is estimated from the diameter of the embryos. To develop the 3D representation, first, all the nuclei are converted from ×, Ƴ, Z coordinates into spherical coordinates (r, θ, ∅). The ∅ and θ measurements are then used to determine into which face of the polyhedron each nuclear point falls. This is done for all nuclei across multiple embryos. Averaging the nuclei in each face together creates an averaged virtual embryo (Fig. 5i).

Another useful representation for visualization, modeling, and testing hypotheses of fluorescent intensity data are one-dimensional graphs extracted in different regions of the embryo data set. To represent the P-Smad5 gradient as a one-dimensional graph around the margin or over the top of the embryo, the P-Smad5 intensities of the closest neighboring cells are averaged. For example, a band of cells approximately 40 μm thick around the vegetal margin can be chosen (Fig. 5j). Cells within that band can be grouped into 10° intervals and averaged together toform 36 individual points. The left and right side of the gradient can be averaged together into a single ventral to dorsal profile (Fig. 5k). Following extraction of the data from the individual embryos, hypothesis testing can be performed to measure the significance of differences between embryos.

4. Notes

Once embryos are dechorionated, only use a glass Pasteur pipette to transfer embryos since they stick to plastic.

It is efficacious to remove the yolk at early stages (4–7 hpf) because the embryos are spherical and difficult to consistently orient for imaging. Without the yolk, embryos naturally settle with their animal poles downward. However, do not remove the yolk after 7 hpf (65–70% epiboly) because doing so will damage embryo morphology.

The Histone H3 antibody is an optional, additional stain for nuclei. Nuclei can also be stained with Sytox Green (in Sect. 3.3 step 5) alone or in combination with the H3 antibody. We find that the Histone H3 antibody marks DNA most evenly and, when combined with its secondary antibody, remains more stable (has little to no background) than Sytox Green when imaging for extended periods of time (>4 h, see next section). Sytox Green can still be sufficient for identifying single nuclei, though its efficacy in our hands decreases after three or more freeze-thaw cycles. We recommend storing Sytox Green at −80 °C in small (2–5 μL) aliquots.

Nuclei can be stained with Sytox Green alone or in addition to Histone H3. If using the Histone H3 antibody, it may still be necessary to stain embryos with Sytox Green so they are visible after being cleared for imaging (see next section). Sytox Green is much brighter and may be more easily seen under the dissecting fluorescent scope, depending on its power and resolution.

Embryos tend to stick to the plastic of the tube after dehydration. Be wary of inverting the tubes after dehydration has begun.

BABB should be mixed fresh just prior to use, and the BABB solution should be clear. Benzyl benzoate (BB) and benzyl alcohol (BA) stocks must be kept tightly closed and away from light to preserve their tissue-clearing ability. Since BABB dissolves plastics, it should be mixed in a glass vial, and embryos should not be left in BABB in plastic tubes for a prolonged period of time (>2 h).

The embryos will no longer be visible to the naked eye. To see the embryos, use a fluorescent dissecting microscope with a green light filter cube to illuminate the Sytox Green.

Method 2 is best for embryos at 70% epiboly and later stages. The ring of grease enables positioning the embryo directly against the surface of the coverslip, as opposed to suspended above it when using the silicon wafer. This is important at later stages because the volume occupied by the cells of the embryo is larger and will challenge the working distance of the objective during imaging. If the embryo is not close to the surface of the coverslip, a large proportion of the embryo will not be imaged.

Once the coverslip touches the BABB in the well, it will seal tightly against the silicon, and removing it will no longer be possible. It may be possible to slide it slightly into place depending on the amount of suction created by the well.

We used the following equipment and settings: an LSM 710 confocal microscope with a LD LCI Plan-Apochromat 25×/0.8 Immersion Corr DIC M27 multi-immersion lens, which has a free working distance of 0.57 mm. We used a 2.4× digital zoom with 4 × 4 tiling and 256 × 256 pixels in each tile, making the stitched image 1024 × 1024 pixels. The × and Ƴ pixel length was 0.55 μm. A pinhole size of 29.5 μm gave a Z-slice thickness of 2.2 μm (for a 633 nm wavelength). We used 488, 561, and 633 nm excitation lasers. The 633 nm laser, which we used to measure P-Smad5 fluorescence, is a 5 mW laser made by Lasos, model LGK 7628–1F. For the channel used to measure P-Smad5, we used 8-bit images, a pixel dwell time of 1.58 μs, a gain between 800 and 950, and no digital offset. We used laser power of 7% for the 633 laser. Z-slices were spaced by 2.2 μm, and approximately 70–190 slices were needed per embryo. Total embryo scan times ranged between 12 min at 30% epiboly and 30 min at the end of gastrulation.

To minimize light scattering by the cells and yolk, we cleared embryos with BABB. If the refractive index (RI) of the immersion lens does not match the RI of the media of the sample, spherical aberrations can distort the Z-dimension of the embryo and cause nonlinear drop-off of intensity along the Z-axis. These effects can be easily visualized by comparing confocal stacks of an embryo emerged in BABB (R.I. ≈ 1.56) taken with a 25× oil-immersion (R.I. = 1.518) lens and a 20× air lens (R.I. = 1) (Fig. 3a). We used the oil-immersion setting of the 25 × lens, since immersion oil, the coverslip, and BABB all have similar R.Is. Also note that most lenses have recommended coverslip thicknesses that must be used to avoid spherical aberration. Here we used Fisherbrand microscope cover glass 12–544-C 24 × 40 — 1.5.

Many lenses, especially high magnification lenses, do not transmit intensity equally across the field of view, and therefore objects near the periphery of the image appear dimmer than they actually are. To determine if this phenomenon is significant to a lens, image a fluorophore dissolved in water or a calibration slide (e.g., Thermo fisher cat. no. F369009, well A1) with a uniform intensity and measure the difference between pixels near the center and the edge of the image. To decrease this effect, increase the digital zoom on the microscope. For example, with the LD LCI Plan-Achromat 25×/0.8 Imm Corr DIC M27 multi-immersion lens at a 0.6× digital zoom, there is ≈40% drop-off from the center to the edge of the image (Fig. 3b, bʹ). When increased to a 2.4× digital zoom, there is only an 8% drop-off from the center to the edge of the image (Fig. 3c, cʹ).

Using a higher digital zoom will decrease the field of view and may require tiling to keep the entire embryo in view. We used 2.4× zoom and 4 × 4 tiling with 256 × 256 pixels in each tile, making the stitched image 1024 × 1024 pixels.

It is important to ensure that the chosen laser power and pixel dwell time does not bleach the sample. Image the same embryo twice and compare the mean intensity to ensure there is little to no drop-off due to bleaching. A drop-off of less than 5% is ideal.

Depending on the type and age of the laser being used (we used a 5 mW laser by Lasos, model LGK 7628–1F), laser power may fluctuate over time. Large fluctuations in laser power will result in systematic differences in fluorescence intensity and must be controlled for when imaging P-Smad5 fluorescence. In general, laser intensity will stabilize after 1–4 h of being turned on and the rate of power drop-off can be measured using an optical power meter (e.g., Thor Labs, PM100A). It is necessary to measure laser power between imaging samples to correct for any change in laser power. This can be done using a test slide containing fluorescent beads (e.g., ThermoFisher cat. no. F369009, well A1). Measuring the fluorescence intensity of an inert fluorescent bead enables the quantification of fluctuations in laser power. Importantly, the same bead must be imaged each time with identical settings (number of slices, gain) since fluorescent beads can differ in their intensity, which will introduce variability in intensity measurements (Fig. 3d, dʹ).

To recover embryos from mounting Method 1, carefully pry the coverslips apart under a dissecting microscope. This process is tedious due to the suction in the well and the invisibility of the embryo. The silicon wafers are reusable after being carefully cleaned with ethanol. To recover embryos from mounting Method 2, carefully lift the short coverslip off of the vacuum grease. Either method may be performed with or without a fluorescent dissecting microscope. If not using a fluorescent microscope, drip methanol into the opened imaging well to make the embryo visible again. Practicing this step beforehand is highly recommended to prevent loss of embryos.

Kernel diameter is important to properly identify nuclei. The kernel diameter should not exceed the diameter of the nucleus or nuclei will be merged. Conversely, too small of a diameter will oversample the same nucleus. Ideally, the kernel diameter should match the average diameter of the nuclei. When the kernel size exceeds the size of the nuclei by so much that it begins including neighboring nuclei, nuclei become merged, and the total number drops off rapidly (Fig. 4aʹʹ).

To calculate the overall image acquisition error for our system, we imaged the same embryo twice by repositioning the slide, reidentifying the embryo, and redetermining the z-stack limits. We paired individual nuclei from the first and second image by finding the nonrepeating correspondence of the closest nuclei from each image (Fig. 4c). Once nuclei had been paired, we measured the difference between them (Fig. 4d). After removing drop-off from photobleaching, an average overall image acquisition noise had a normal distribution with a σ = 6.4% ± 0.3%, which includes positioning error and detector noise (Fig. 4d).

To decrease the amount of processing power needed and increase accuracy, embryos should first be aligned in the AV and DV direction BEFORE attempting CPD to fit experimental embryos to a template embryo.

Embryos stained on different days or imaged with different settings can be normalized by multiplying the entire set by a single scalar value. Embryos stained in the same tube and imaged using the same confocal settings on the same day do not need to be subjected to normalization, provided that laser power fluctuations do not occur (see Fig. 3dʹ). To determine the normalization scalar, control WT embryos should always be imaged in conjunction with each experimental condition. The scalar normalization value is determined by minimizing the sum of the error between the control WT embryos imaged on different days.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grant NIH R01GM056326 and NIH R01HD073156.

References

- 1.Gregor T, Wieschaus EF, McGregor AP, Bialek W, Tank DW (2007) Stability and nuclear dynamics of the bicoid morphogen gra dient. Cell 130(1):141–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teleman AA, Cohen SM (2000) Dpp gradient formation in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc. Cell 103(6):971–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coppey M, Boettiger AN, Berezhkovskii AM, Shvartsman SY (2008) Nuclear trapping shapes the terminal gradient in the Drosophila embryo. Curr Biol 18:915–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregor T, Tank DW, Wieschaus EF, Bialek W (2007) Probing the limits to positional information. Cell 130(1):153–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves GT, Trisnadi N, Truong TV, Nahmad M, Katz S, Stathopoulos A (2012) Dorsal-ventral gene expression in the Drosophila embryo reflects the dynamics and precision of the dorsal nuclear gradient. Dev Cell 22(3):544–557. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaeger J, Surkova S, Blagov M, Janssens H, Kosman D, Kozlov KN, Manu ME, Vanario-Alonso CE, Samsonova M, Sharp DH, Reinitz J (2004) Dynamic control of positional information in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature 430(6997):368–371. 10.1038/nature02678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umulis DM, Shimmi O, O ‘Connor MB, Othmer HG (2010) Organism-scale modeling of early Drosophila patterning via bone morpho-genetic proteins. Dev Cell 18(2):260–274. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanodia JS, Rikhy R, Kim Y, Lund VK, DeLotto R, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Shvartsman SY (2009) Dynamics of the Dorsal morphogen gradient. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (51):21707–21712. 10.1073/pnas.0912395106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuazon FB, Mullins MC (2015) Temporally coordinated signals progressively pattern the anteroposterior and dorsoventral body axes. Semin Cell Dev Biol 42:118–133. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubrulle J, Jordan BM, Akhmetova L, Farrell JA, Kim Sh, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF (2015) Response to Nodal morphogen gradient is determined by the kinetics of target gene induction. Elife 4:e05042 10.7554/eLife.05042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller P, Rogers KW, Jordan BM, Lee JS, Robson D, Ramanathan S, Schier AF (2012) Differential diffusivity of Nodal and Lefty underlies a reaction-diffusion patterning system. Science 336(6082):721–724. 10.1126/science.1221920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey SA, Smith JC (2009) Visualisation and quantification of morphogen gradient formation in the zebrafish. PLoS Biol 7(5): e1000101 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Boxtel AL, Chesebro JE, Heliot C, Ramel MC, Stone RK, Hill CS (2015) A temporal window for signal activation dictates the dimensions of a nodal signaling domain. Dev Cell 35(2):175–185. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimozono S, Iimura T, Kitaguchi T, Higashijima S, Miyawaki A (2013) Visualization of an endogenous retinoic acid gradient across embryonic development. Nature 496 (7445):363–366. 10.1038/nature12037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sosnik J, Zheng L, Rackauckas CV, Digman M, Gratton E, Nie Q, Schilling TF (2016) Noise modulation in retinoic acid signaling sharpens segmental boundaries of gene expression in the embryonic zebrafish hindbrain. Elife 5: e14034 10.7554/eLife.14034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimmi O, Umulis D, Othmer H, O ‘Connor MB (2005) Facilitated transport of a Dpp/Scw heterodimer by Sog/T sg leads to robust patterning of the Drosophila blastoderm embryo. Cell 120(6):873–886. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bollenbach T, Pantazis P, Kicheva A, Bokel C, Gonzalez-Gaitan M, Julicher F (2008) Precision of the Dpp gradient. Development 135 (6):1137–1146. 10.1242/dev.012062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavin-Smyth J, Wang YC, Butler I, Ferguson EL (2013) A genetic network conferring canalization to a bistable patterning system in Drosophila. Curr Biol 23(22):2296–2302. 10.1016/jxub.2013.09.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tucker JA, Mintzer KA, Mullins MC (2008) The BMP signaling gradient patterns dorsoventral tissues in a temporally progressive manner along the anteroposterior axis. Dev Cell 14 (1):108–119. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashiguchi M, Mullins MC (2013) Antero-posterior and dorsoventral patterning are coordinated by an identical patterning clock. Development 140(9):1970–1980. 10.1242/dev.088104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaspro A, Federici F, Robello M (2002) Influence of refractive-index mismatch in high-resolution three-dimensional confocal microscopy. Appl Opt 41(4):685–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azaripour A, Lagerweij T, Scharfbillig C, Jadczak AE, Willershausen B, Van Noorden CJ (2016) A survey of clearing techniques for 3D imaging of tissues with special reference to connective tissue. Prog Histochem Cytochem 51(2):9–23. 10.1016/j.proghi.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller PJ, Schmidt AD, Wittbrodt J, Stelzer EH (2008) Reconstruction of zebrafish early embryonic development by scanned light sheet microscopy. Science 322(5904):1065–1069. 10.1126/science.1162493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myronenko A, Song X (2010) Point set registration: coherent point drift. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 99 (RapidPosts) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myronenko A, Song X, Carreira-Perpinan MA (2007) Non-rigid point set registration: coherent point drift. Adv Neural Inf Proces Syst 19:1009–1016 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Truett GE, Heeger P, Mynatt RL, Truett AA, Walker JA, Warman Ml (2000) Preparation of PCR-quality mouse genomic DNA with hot sodium hydroxide and tris (HotSHOT). Bio-techniques 29(1):52, 54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith SM, Maughan PJ (2015) SNP genotyping using KASPar assays. Methods Mol Biol 1245:243–256. 10.1007/978-1-4939-1966-6_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.N eff MM, Neff JD, Chory J, Pepper AE (1998) dCAPS, a simple technique for the genetic analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms: experimental applications in Arabidopsis thaliana genetics. Plant J 14 (3):387–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myronenko A, Song X (2010) Point set registration: coherent point drift. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 32(12):2262–2275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]