Abstract

Purpose

Research in the education domain has noted the importance of work-based passion and has repeatedly highlighted how passion influences positive work outcomes. However, far too little attention has been given to investigating whether one’s passion can be transferred to others. Using two theoretical lenses – crossover theory (CT) and emotional contagion theory (ECT) – the present study intends to deepen our understanding by examining whether a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student.

Methods

To address this knowledge gap, we recruited students and their subject teachers (n=226 teacher-student dyads) from the major business schools of Pakistan, based on the convenience sampling method, during the period from November to December 2018. An exploratory factor analysis was run to extract the dimension underlying each construct. A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using AMOS 24.0 to assess the discriminant and convergent validity of the measurement model. The SPSS PROCESS macro was used to test the hypotheses using SPSS 24.0.

Results

Consistent with the hypotheses, our results show that a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student’s work passion indirectly via emotional contagion. Our data further establish that the transference of a teacher’s work passion to a student’s work passion via emotional contagion is more significant when the teacher is educated at PhD level than when she/he is non-PhD educated.

Conclusion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study has been one of the first attempts to thoroughly examine work passion transference from teachers to students in the area of higher education and offers several managerial and theoretical implications alongside future opportunities for practitioners and research scholars.

Keywords: work passion, emotional contagion, teacher’s education, moderated mediation model

Introduction

Interest in the concept of work passion has grown in the new millennium, with a surge in the number of studies emphasizing the positive outcomes of work passion and how organizations can benefit from a passionate workforce.1–3 Work passion refers to a tendency towards an act or activity that people like, see as important, and invest significant time and energy in.4,5 Passion fuels motivation, increases wellbeing and gives meaning to individuals’ lives. Academic research in the management domain has linked passion with positive work outcomes and recognized it as an inevitable component for wellbeing, growth, and entrepreneurial success.6–10 Work passion disposes individuals towards dedication to their work, which allows them to continue their work even in the face of obstacles and to achieve excellence.11 Work is important because it is part of a person’s identity and gives meaning to their life.4,12 Research shows that although individuals value their work, their engagement in work varies from person to person, and this has important ramifications.10 The motivational perspective of passion suggests the mechanisms through which one can identify different patterns of energy and time invested in different activities, which impact people’s affection and behaviors.10,13

An increasing number of studies guided by the theoretical notion of ‘crossover’ have reported the transference of passion from one individual to another in different domains of life.1,9,14 For example, a study conducted by Cordon8 reported the transference of passion from entrepreneurs to employees. In the management domain, Li et al.9 have shown the transference of work passion from leaders to followers. Similarly, in the marketing domain, Gilal et al.1 have reported the transference of brand passion from parents to children. Despite the fact that these studies provide an insight into passion transference, the potential for discovering whether a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student remains largely untapped. Academic research in the educational context suggested that around 80% of adolescents in schools get passion from situational contexts15 and that what teachers do in the classroom can help students to develop their passion.16 On the basis of these beliefs and the theoretical notion of crossover theory, the current study aims to examine whether a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student.

In psychological research, a theoretical framework is increasingly being applied that advances the theory that the attitudes, emotions, behaviors, and beliefs of one individual can be transmitted to others; this is known as emotional contagion.17 Emotional contagion theory (ECT) is one of the leading psychological theories which posits that people can “catch” the positive actions and emotions of others during their social interactions.1 This is known as a trickledown effect, where one’s actions can provoke similar responses in others.18 Empirical research by Cordon,8 in the context of management, reported the transference of an entrepreneur’s passion to employees via emotional contagion. The study by Li et al.9 in the same context suggests that emotional contagion facilitates the transmission of a leader’s work passion to their subordinates. In the context of brand management, the study by Gilal et al.1 confirmed that the brand passion of parents can be transferred to children via the mediation of emotional contagion. Based on the findings of the above-cited studies and the theoretical notion of ECT, we suggest that the mediation of emotional contagion may facilitate the association between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s passion. Therefore, we propose emotional contagion as a mediating variable to investigate whether a teacher’s work passion can be translated into a student’s work passion via emotional contagion.

In addition to testing the mediation, the current research also aims to examine the boundary conditions for work passion transference by studying the moderating effect of the teacher’s education – that is, whether a higher level of education in a teacher (i.e., non-PhD vs. PhD) can enhance or undermine the transference of work passion from teacher to student through emotional contagion. A study conducted by Jillapalli & Wilcox19 in the context of human branding suggests that teachers become a source of inspiration and evoke positive emotional responses among students, becoming a lifestyle aspiration for them. Based on this, we believe that teachers who have a higher qualification (i.e., PhD) will have a more prominent influence than those holding only an MS/Masters degree (i.e., non-PhD). Therefore, we aim to explore whether a teacher’s education moderates the link between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s passion via emotional contagion.

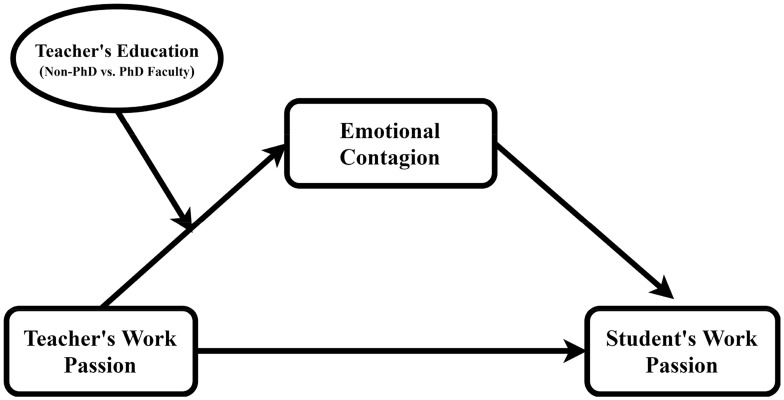

In summation, our study proposes a moderated mediation model that builds on the prior research of Gilal et al.1,5 to answer three under-researched questions in the settings of management and higher education. First, this study contributes to an exploration of whether a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student. Second, our study examines the mediation of emotional contagion in the relationship between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s work passion – that is, whether emotional contagion strengthens or facilitates work passion transference. Third, we provide additional evidence with respect to work passion transference by studying the moderation of a teacher’s education on the relationship between a teacher’s work passion and their student’s passion via emotion contagion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed theoretical model.

Literature review

Passion is a tendency towards an act or activity that people like, see as important, and invest significant time and energy in.1,9,16,20 There are two different positions that researchers take in the study of passion. According to the first position, reason stimulates acceptable thoughts, while unacceptable thoughts are caused by passion. This logic suggests that passion causes a loss of reason and control.21 This perspective sees individuals as slaves of their passion, with their passion controlling them.21 The second perspective is more positive and it depicts individuals as being more active in relation to their passion. This view suggests that when individuals are controlled by their passion, adaptive benefits will be increased over time.21

Much of the research conducted in this field predominantly focuses on work performance; very limited research has been done so far on passion in education. The few available studies focusing on this area investigated the influence of passion on the student. Studies such as Ruiz-Alfonso & León,16,22 Coleman & Guo,23 Day,24 and Liston & Garrison25 suggest that passion is also important in an educational context and that it impacts the performance of both teachers and students. While the majority of research in the domain of passion follows the conceptualization of Vallerand et al,21 authors in the educational context have also tried to define passion. For example, Coleman & Guo23 used the term “passion for learning” to describe the interest of a student in a particular domain, which, in spite of difficulties, has endured over time and is normally associated with a relative disinterest towards activities that are interesting for other individuals. The concept of passion has been studied from a teacher’s perspective by Liston & Garrison.25 They focused on the passion that teachers have for teaching or towards the subject they teach. Passion is defined by Liston & Garrison25 as the teacher’s love for the task of educating people and for their students. Day24 defines passion as the love of teachers for the belief that teaching enables them to influence the lives of their students, and love for the subject they teach.

A growing number of researchers have focused on the effects of passion within an educational context, and they have linked passion to students’ performance, deliberate practice, persistence, goal orientation, motivation to learn, resilience, and well-being.3,11,16,26–35 Studies have shown that as the passion of a learner increases, there is a greater tendency to remain focused on improving self-competence.11,16,27–29,31

A considerable body of research guided by crossover theory has also explored whether one’s passion can be transferred to others.1,8,9,14 As such, Gilal et al,1 in the context of brand management, reported the transference of airline brand passion from parents to children. Similarly, in a leadership context, Cardon8 explored whether an entrepreneur’s work passion can be transferred to employees and revealed that entrepreneurial passion and the transformational leadership of an entrepreneur creates contagion that leads towards increased employee passion. In a management context, Li et al.9 examined the relationship between a leader’s work passion and their employees’ work passion and suggested that when a passionate leader demonstrates his/her passion frequently and shares a positive association with work, over a period of time employees acquire this emotion and they also start to experience work passion. Based on the results of the above-cited studies and crossover theory, we believe that in an educational context a teacher’s passion can be translated to a student’s passion. With this thought in mind, we predict:

Hypothesis 1: A teacher’s work passion relates positively to a student’s work passion.

A growing number of studies have demonstrated that individuals normally mimic the positive emotions (such as facial expressions, postures, gestures, speech rates, etc.) of trusted people, both consciously and unconsciously.1,36,37 For example, a recent publication by Li et al.9 viewed emotional contagion as a process through which an individual or a group of individuals influences another individual or group of individuals’ behavior, attitude, and affective state through conscious or subconscious emotional mimicry.

Literature suggests that during their social encounters, people mimic or “catch” the emotions of others.1 Research further suggests that people copy the emotions of people with whom they are familiar more quickly and readily.38 Studies in a leadership context have suggested that emotional contagion relates positive effects in a leader to positive effects in their followers at work.18,39,40 A recent article by Moeller et al.15 highlighted that external agents have the scope of action in the development of passion. Particularly in an educational context, research suggests that students develop passion by observing the actions of the teacher in the classroom.16,22 Based on the results of above-cited studies and emotional contagion theory, we believe that a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student via emotional contagion. Consequently, we predict:

Hypothesis 2: Emotional contagion will mediate the link between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s work passion.

Along with the mediating role of emotional contagion, the current study also aims to explore the moderation of a teacher’s educational level on the relationship between the teacher’s work passion and emotional contagion. In other words, the effect of a teacher’s work passion on a student’s work passion varies with the teacher’s educational level. A number of studies conducted in an educational context suggest that the qualification of teachers is one of the critical factors that influences students’ learning.41,42 The effective teaching capability of a teacher is related to his/her qualification – the more qualified a teacher is, the more effective he/she is at teaching.43 Moreover, there are a number of studies that suggest that students’ outcomes are directly related to the teacher’s qualification.44 Therefore, we believe that the effect of a teacher’s work passion on a student’s work passion via emotional contagion is particularly relevant with teachers who have a PhD degree. A study conducted by Jillapalli & Wilcox,19 in a human branding context, suggests that teachers become a source of inspiration and evoke positive emotional responses among their students, ultimately becoming a lifestyle aspiration for them. Therefore, we believe that a higher level of education for the teacher – i.e., having a PhD – can more strongly inspire students to mimic the positive behaviors of their teacher. In light of these arguments; we formally propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: A teacher’s education (non-PhD vs. PhD) moderates the mediated effect of a teacher’s work passion on a student’s work passion through emotional contagion.

Methods

Ethical statement

The present research was approved by the offices of research, innovation, and commercialization (ORIC) of Sukkur IBA University, and by the ethics review committees. All respondents voluntarily participated in this study and written informed consent was obtained from them as per the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants and procedure

Using procedures from the extant research,20 we distributed 300 questionnaires to students and their teachers from different disciplines and degree programs at five public-sector universities located in the major cities of Pakistan. The subject teachers facilitated data collection. Students completed the questionnaires to provide information about demographics, emotional contagion, and their passion. Teachers completed the questionnaires to enable the researchers to assess their demographic profiles and work passion. After evaluating the returned surveys, the total number of effective matching responses was n=226, resulting in a 75.33% response rate. According to Baruch & Holton,45 there is no threshold for response rate in survey research; however, they recommend a response rate of 50% as acceptable on an individual level. Following these recommendations, we can infer that the response rate of 75.33% is sufficient to conduct the analysis. Of the initial cohort of 226 teacher-student dyads, the age of teachers ranged from 25 to 55 years. Among these, 68.6% were male teachers; 61.9% had a Masters/MS degree; 46.5% had a work experience ranging from one to five years; and 53.1% were lecturers while the remaining 46.9% were professors (e.g., assistant, associate, or full professor). Similarly, the age of students ranged from 18 to 40 years. Among surveyed students, 74.3% were male, 94.7% were unmarried, and 90.3% were pursuing a bachelor’s degree. The detailed demographic information of the participants is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of sample

| Criterion | Characteristics | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (Teachers): | 25–30 | 33.2 |

| 30–35 | 19.9 | |

| 35–40 | 33.2 | |

| Above 40 | 13.7 | |

| Gender (Teachers): | Female | 31.4 |

| Male | 68.6 | |

| Education (Teachers): | Non-Ph.D. Faculty | 61.9 |

| Ph.D. Faculty | 38.1 | |

| Experience (Teachers): | 1–5 years | 46.5 |

| 5–10 years | 26.5 | |

| More than 10 years | 27.0 | |

| Job title (Teachers): | Lecturer | 53.1 |

| Assistant Professor | 26.5 | |

| Associate Professor | 10.6 | |

| Professor | 9.7 | |

| Age (Students) | 18–30 | 97.8 |

| 30–35 | 1.3 | |

| Above 40 | 0.9 | |

| Gender (Students) | Female | 25.7 |

| Male | 74.3 | |

| Marital status (Students) | Married | 5.3 |

| Single, never married | 94.7 | |

| Education (Students) | Bachelor’s degree | 90.3 |

| Master’s degree | 8.0 | |

| MS degree | 0.9 | |

| Ph.D | 0.9 |

Note: Sample size (N)=226.

Instrument

Like many cross-sectional studies,2,46,47 we adapted all scale items from prior research, and the instrument was pretested with 15 teacher-student dyads. We asked subjects to indicate their agreement/disagreement with the series of items given using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). To measure teachers’ work passion and students’ passion, we borrowed 14 items relating to each from Gilal et al.1,2 Similarly, we adapted 15 items relating to emotional contagion from Cohen et al,48 Doherty,49 and Gilal et al.1,2 The Cronbach’s alpha for a teacher’s work passion, a student’s passion, and emotional contagion scales were 0.954, 0.935, and 0.983 respectively.

Results

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

Before testing the measurement and hypothesized model, we ran EFA using the principal axis factoring method and varimax rotation on three variables (i.e., teacher’s work passion, emotional contagion, and student’s work passion) to extract the dimensions underlying each construct. The EFA results yielded a three-factor solution explaining 76.341% of the total variance; however, four items of teacher’s work passion (i.e., TWP1, TWP3, TWP13, and TWP14), eight items of emotional contagion (i.e., EC5, CE6, EC7, EC8, EC9, EC10, EC13, EC14), and six items of student’s work passion (i.e., SWP5, SWP10, SWP11, SWP12, SWP13, SWP14) were not applicable in the present research context because of a factor score of below 0.40. Thus, we dropped them from the analysis.50,51 Our EFA findings further reveal that Bartlett’s test equals 6267.074: p<0.001 and that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was greater than the required threshold of 0.6 (KMO =0.955). Hence, it is considered a good fit.50,51 Table 2 shows the detailed EFA results.

Table 2.

Factor loadings of exploratory factor analysis for the 3-factor model

| Items | Teacher’s Work Passion | Emotional Contagion | Student’s Work Passion |

|---|---|---|---|

| TWP8 | 0.829 | ||

| TWP6 | 0.827 | ||

| TWP9 | 0.827 | ||

| TWP5 | 0.809 | ||

| TWP11 | 0.803 | ||

| TWP4 | 0.802 | ||

| TWP7 | 0.784 | ||

| TWP2 | 0.782 | ||

| TWP12 | 0.780 | ||

| TWP10 | 0.746 | ||

| EC11 | 0.861 | ||

| EC12 | 0.858 | ||

| EC3 | 0.846 | ||

| EC4 | 0.839 | ||

| EC2 | 0.839 | ||

| EC15 | 0.811 | ||

| EC1 | 0.810 | ||

| SWP8 | 0.872 | ||

| SWP6 | 0.832 | ||

| SWP7 | 0.807 | ||

| SWP4 | 0.804 | ||

| SWP3 | 0.799 | ||

| SWP1 | 0.759 | ||

| SWP2 | 0.746 | ||

| SWP9 | 0.702 | ||

| Eigenvalue | 13.075 | 4.033 | 1.977 |

| % of Variance | 52.300 | 16.133 | 7.909 |

| Cumulative % of Variance | 52.300 | 68.432 | 76.341 |

Notes: K-M-O Measure of sampling adequacy =0.955; Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity =6267.074: p<0.001.

Abbreviations: TWP, teacher’s work passion; EC, emotional contagion; SWP, student’s work passion.

Convergent validity

After the EFA analysis, we conducted a CFA in AMOS 24.0 to test the convergent validity. Our results suggest that the composite reliability (CR) for teacher’s work passion (=0.955), emotional contagion (=0.983), and student’s passion (=0.936) meet the recommended threshold. Likewise, the average variance extracted (AVE) for teacher’s work passion (=0.679), emotional contagion (=0.891), and student’s passion (=0.645) were also above the recommended threshold value.52 Thus, the findings displayed in Table 3 confirm the convergent validity of the measurement instruments.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity

| Dimension | Item | Standardized Factor Loading | Squared Multiple Correlations | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher’s Work Passion | TWP8 | 0.838 | 0.702 | 0.954 | 0.955 | 0.679 |

| TWP6 | 0.833 | 0.693 | ||||

| TWP9 | 0.886 | 0.785 | ||||

| TWP5 | 0.889 | 0.791 | ||||

| TWP11 | 0.832 | 0.693 | ||||

| TWP4 | 0.799 | 0.639 | ||||

| TWP7 | 0.857 | 0.735 | ||||

| TWP2 | 0.793 | 0.630 | ||||

| TWP5 | 0.755 | 0.571 | ||||

| TWP10 | 0.744 | 0.554 | ||||

| Emotional Contagion | EC11 | 0.949 | 0.900 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.891 |

| EC12 | 0.966 | 0.934 | ||||

| EC3 | 0.963 | 0.927 | ||||

| EC4 | 0.947 | 0.898 | ||||

| EC2 | 0.955 | 0.911 | ||||

| EC15 | 0.925 | 0.856 | ||||

| EC1 | 0.899 | 0.808 | ||||

| Student’s Work Passion | SWP8 | 0.865 | 0.748 | 0.935 | 0.936 | 0.645 |

| SWP6 | 0.824 | 0.678 | ||||

| SWP7 | 0.786 | 0.618 | ||||

| SWP4 | 0.809 | 0.655 | ||||

| SWP3 | 0.806 | 0.650 | ||||

| SWP1 | 0.796 | 0.633 | ||||

| SWP2 | 0.795 | 0.631 | ||||

| SWP9 | 0.742 | 0.550 |

Abbreviations: TWP, teacher’s work passion; EC, emotional contagion; SWP, student’s work passion.

Discriminant validity

The discriminant validity was examined by comparing a three-factor model (ModelA) with a two-factor model (ModelB) and a one-factor model (ModelC). Our findings demonstrate that the three-factor model (ModelA), which comprised ten items of teacher’s work passion, seven items of emotional contagion, and eight items of student’s work passion, revealed excellent goodness-of-fit values [χ2 (25)=1.892; CFI=0.961; NFI=0.921; TLI=0.957; GFI=0.846; SRMR=0.053; RMSEA=0.063] compared to the other nested models, suggesting that the subjects distinguish all variables under study. Table 4 provides more detailed results.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity

| Model | Factor Loaded | X2/df | CFI | NFI | TLI | GFI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Three Factor | 1.892 | 0.961 | 0.921 | 0.957 | 0.846 | 0.053 | 0.063 |

| B | Two Factor | 6.232 | 0.770 | 0.739 | 0.748 | 0.442 | 0.175 | 0.152 |

| C | One Factor | 9.254 | 0.636 | 0.61 | 0.603 | 0.346 | 0.229 | 0.192 |

Bivariate correlation

The results displayed in Table 5 show that teacher’s work passion relates significantly to emotional contagion (r=0.629**) and student’s work passion (r=0.352**). Likewise, correlation analysis has further revealed that emotional contagion relates significantly to the student’s work passion (r=0.586**). In summation, these results fully support a significant positive association between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s work passion.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

| Variables | Mean | SD | Teacher’s work passion | Emotional Contagion | Student’s work passion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher’s work passion | 4.347 | 0.96 | 1 | ||

| Emotional Contagion | 4.273 | 0.94 | 0.629** | 1 | |

| Student’s work passion | 4.291 | 0.95 | 0.352** | 0.586** | 1 |

Note: **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Mediating effect: emotional contagion

The mediation of emotional contagion on the link between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s work passion was examined using SPSS 24.0. ModelA in Table 6 suggests that the teacher’s work passion has a statistically significant impact on the student’s work passion (β=0.352***). Therefore H1 is supported by our data.

Table 6.

Regression results for testing mediating of emotional contagion

| Variables | Model A (Dependent variable: SWP) | Model B (Dependent variable: EC) | Model C (Dependent variable: SWP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.772*** | 1.581*** | 1.814*** |

| TWP | 0.352*** | 0.629*** | −0.027ns |

| EC | – | - | 0.602*** |

| F | 31.745 | 146.635 | 58.333 |

| R2 | 0.124 | 0.396 | 0.343 |

Notes: Level of significance: ***p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: TWP, teacher’s work passion; EC, emotional contagion; SWP, student’s work passion; ns, non-significant.

In a similar vein, after we added emotional contagion into the regression models (ModelB & ModelC), the impact of the teacher’s work passion on the student’s passion was found to be statistically insignificant (β=−0.027, P=ns). Furthermore, ModelC revealed the strong positive influence of emotional contagion on student’s passion (β=0.602***), which supports H2. Thus, it is concluded that emotional contagion completely mediates the association between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s work passion.

Moderating effect: teacher’s education

Our Hypothesis 3, relating to the interaction effect of a teacher’s education on the association between the teacher’s work passion and the student’s work passion via emotional contagion, was examined using the procedure suggested by Hayes.53,54 Consistent with the hypothesis, our data revealed a statistically significant interaction effect of teacher’s work passion and teacher’s education on emotional contagion (β=0.453***). To further examine to what degree the transference of work passion from teachers to students via emotional contagion is relevant in teachers whose education is non-PhD compared to those who hold a PhD, we plotted the interaction effect as suggested by Aiken, West, & Reno.55 Our findings show that the impact of a teacher’s work passion on emotional contagion is more prominent when the teacher’s education is at PhD level (β=0.760***p<0.001: CI=0.641–0.878) than when it is at non-PhD level (β=0.307***p<0.001: CI=0.133–0.480). Table 7 displays detailed results.

Table 7.

Results of moderation analysis

| Predictor | Beta Coefficient | t-value | p-value | f | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TWP | 0.587 | 11.689 | 0.000 | 58.658 | 0.442 | |

| Education | 0.107 | 1.084 | 0.279 | |||

| TWP x Teacher’s Education | 0.453 | 4.239 | 0.000 | |||

| Teacher’s education | Conditional Effect | SE | t-value | p-value | LLCI | ULCI |

| Non-PhD Faculty | 0.307 | 0.088 | 3.475 | 0.001 | 0.133 | 0.480 |

| PhD Faculty | 0.760 | 0.060 | 12.59 | 0.000 | 0.641 | 0.878 |

Abbreviations: TWP, teacher’s work passion; LLCI, lower limit confidence interval; ULCI, upper limit confidence interval.

Discussion

The present study provides additional evidence with respect to passion research by testing a moderated mediation model of work passion transference from teachers to students under the theoretical lenses of crossover theory and emotional contagion theory. In particular, the present study makes three noteworthy contributions to management and education research. First, this study contributes to a growing body of passion literature by exploring whether a teacher’s work passion can be translated into a student’s passion. Second, our study contributes to an investigation of whether emotional contagion facilitates the transference of work passion from teachers to students – that is, whether emotional contagion plays a mediating role to facilitate the transference of passion in a higher education setting. Third, the present study provides additional evidence by examining whether the teacher’s education (i.e., non-PhD. vs. PhD.) moderates the mediation effect of emotional contagion on the relationship between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s passion.

Consistent with our expectations, the findings relating to H1 supported a significantly positive relationship between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s passion in an educational setting. This can be attributed to the fact that, just as children receive brand preferences from their parents,1 students may also learn the work-related behavior of trusted teachers. The finding observed in this study mirrors those of prior studies that have examined the transmission of brand passion from parents to children,1 from leaders to employees,9 and from entrepreneurs to employees.8

Likewise, our findings regarding the indirect influence of emotional contagion on the relationship between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s passion suggest that, after adding emotional contagion as mediating variable in the model, the influence of a teacher’s work passion on a student’s passion is statistically insignificant, indicating that emotional contagion completely mediates the association between a teacher’s work passion and a student’s passion. This can be put down to the fact that individual behavior can be strengthened by other people’s modeling of behavior. Our data support this theory and suggests that a teacher’s work passion can be translated into a student’s passion when students emulate or mimic the working behavior of their favorite teachers (i.e., emotional contagion). Therefore, a teacher can serve as a role model by showing his/her genuine interest and enjoyment in teaching and research.

Finally, our results relating to the moderating factor of a teacher’s education (i.e., non-PhD vs. PhD) reveal that the effect of a teacher’s work passion on emotional contagion is dependent on the teacher’s education level. Specifically, our findings suggest that the effect of a teacher’s work passion on a student’s passion is more important when the teacher’s education is at the PhD level than when it is at the non-PhD level. This could be because students are inspired by highly educated faculty members, as they have a more substantive knowledge of the subject and experiences that ultimately inspire students to work with the same passion as their teachers.22 The present findings seem to be consistent with those of other investigations42,56 that reported a considerable influence of teacher education on student achievements.

Implications for research

The findings of this study have a number of important implications for theory and research. Although extensive research has been carried out to explore the antecedents1,2 and consequences57,58 of passion in psychology and marketing domains, no single study exists that adequately examines the transference of work passion from teacher to student. Hence, this work contributes to passion literature by investigating whether a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student’s passion in the area of education. In particular, this research makes the following noteworthy theoretical contributions. First, we draw on crossover theory to explain the transference of work passion from teachers to students. Our research reveals that a teacher’s work passion can be translated into their student’s work passion. Thus, the present study contributes to an extension of the crossover theory framework by suggesting that, in the field of education, a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student.

We establish the validity of emotional contagion theory (ECT) in the area of education. ECT posits that one’s behavior, attitude, and cognition can be transferred to others and that individuals tend to express/feel emotions that are similar to those of others.1 In line with this theoretical notion, the present research extends our understanding by linking a teacher’s work passion to their student’s via the mediation of emotional contagion in an education setting. Specifically, our study highlights that emotional contagion facilitates the transference of work passion from teachers to students.

In order to better understand the transference of work passion from teachers to students via emotional contagion, the moderating effect of the teacher’s education (i.e., non-PhD. vs. PhD) was examined. Although some research has been carried out on the influence of the teacher’s gender,59,60 the teacher’s age,61 and how the teacher dresses,62 no research was apparent that has explored the moderation of the teacher’s education. This study goes one step further by exploring the moderation of the teacher’s education on the transferal of work passion from teachers to students. Specifically, we have illuminated the importance of the teacher’s education and how this matters in increasing a student’s passion. Therefore, our research contributes to an extension of passion literature by providing a more comprehensive view of the significance of a teacher’s education in improving a student’s passion for work.

The findings of this study have a number of important implications for educational strategists in general and the governing authorities of higher education institutions in particular. Our study has established the importance of a teacher’s work passion as a strategic tool in improving students’ work passion. Our findings show that the teacher’s work passion is an important means of increasing passion among students. Thus, taking into account the findings of the present study, educators and strategists of higher education institutions who seek to increase students’ passion are encouraged to invest in building teachers’ capacity for high-quality teaching by increasing their knowledge (i.e., sending faculty either to their home countries or westward to pursue higher education), and in preparing teachers for higher education teaching.

Our study confirms the full mediation of emotional contagion, which significantly facilitates the transference of a teacher’s work passion to the student. This finding suggests that a teacher’s work passion can be translated into a student’s work passion when pupils emulate or mimic the positive emotions of their teachers. Similarly, this finding also signifies that when students do not emulate or mimic the positive working behavior of their favorite teachers, work passion may not be diffused among students. Thus, educational strategists may benefit from these findings, and they are encouraged to use impression management techniques to inspire and influence students’ perceptions, attitudes, and behavior.

Finally, it is of utmost importance for higher education strategists to direct their attention and efforts towards teachers’ education. Our data establish that the transference of a teacher’s work passion to a student via emotional contagion is more significant when the teacher’s education is at PhD level than when it is at the non-PhD level. Based on these findings, strategists in higher education commissions in general, and recruiters/hiring managers in higher education institutions in particular, are encouraged to create an effective hiring process by revisiting faculty recruitment and selection policies for the appointment of the best candidates based on their higher education and qualifications to ensure the best quality education.

Limitations and opportunities for future research

The findings in this research are subject to at least three limitations. First, this study aimed to examine whether a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student by recruiting participants from higher education institutions in Pakistan. This finding may not be applicable/generalizable in other educational settings/contexts such as the transference of work passion from college teachers to college students or the transmission of school teachers’ work passion to school students. Thus, further research needs to be done to establish whether a school or college teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a school or college student.

Although the study has successfully demonstrated that work passion transference from teacher to student takes place through emotional contagion, an issue that was not addressed in the present research was whether it is obsessive or harmonious work passion that can be transmitted from teacher to student, as in the current study we took a composite score of all the work passion items rather than a score based on the individual facets. Vallerand et al.4 developed a dualist model of passion that categorized passion into two types: harmonious and obsessive. Harmonious passion is defined as a passion for an activity that is in harmony with other life activities.20,63 This type of passion is associated with positive outcomes for the activity. Obsessive passion, on the other hand, is internal pressure that forces a person to engage in the chosen activity.20,63 In contrast with harmonious passion, this type of passion is in conflict with other life activities and is associated with negative outcomes for the activity. In light of the above conception, it is uncertain whether these two dimensions of work passion will transfer similarly between a teacher and a student. It is recommended that further research be undertaken to determine to what extent a teacher’s obsessive vs. their harmonious work passion is transferable to the student.

The present study has developed a moderated mediation model to examine whether a teacher’s work passion can be transferred to a student in a higher education context. This study opens a new window for discussion and provides an exciting opportunity to advance our knowledge by testing the hypotheses of the present study in different domains of life. For instance, it would be fascinating to inspect whether one’s environmental passion can be transferred to another.64,65 In particular, it would be interesting to assess whether a teacher’s environmental passion can be transferred to a student. Likewise, there are opportunities to investigate whether one’s passion for any profession (e.g., newscaster, banker, businessman/woman, singer, actor, etc.) can be transferred to others –for instance, whether a mother’s/father’s nursing passion can be transferred to a son/daughter,66 or whether a mother’s/father’s passion for wearing fashionable clothing can be transferred to a son/daughter.1,2 This research has thrown up many questions in need of further investigation.

In a similar vein, our data establish that the transference of a teacher’s work passion to a student via emotional contagion is more significant when the teacher’s education is at PhD level than when it is at the non-PhD level. An issue that was not addressed in the present research was that of the separate influences of a female PhD teacher on a female student, a male PhD teacher on a male student, a female PhD teacher on a male student, and a male PhD teacher on a female student – this was not examined because of the uneven group sizes and a relatively small number of PhDs. This limitation means that study findings need to be interpreted cautiously. Therefore, it would be interesting to compare the separate effects of the above-discussed dyads in order to generalize the findings. Despite these limitations, this study fills the existing research gap in higher education literature by reporting on the transference of a teacher’s work passion to students via emotional contagion.

Conclusion

The present study was designed to examine work passion transference from teachers to students in the area of higher education. A systematic literature review suggested that an increasing number of researchers have emphasized how passion influences individuals’ psychological states and positive work consequences. The present study tested a theoretical framework comprised of “Teacher’s work passion” as the independent variable and “Teacher’s education” (i.e., non-PhD vs. PhD) and “Emotional contagion” as moderating and mediating variables respectively, to capture the transference of work passion from teachers to students. Our data established that the transference of a teacher’s work passion to a student via emotional contagion is more significant when the teacher’s education is at PhD level than when it is at the non-PhD level. With this consideration in mind, the empirical findings in this study have opened a window of discussion and provided room for fascinating future research agendas.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Gilal FG, Zhang J, Gilal NG, Gilal RG. Association between a parent’s brand passion and a child’s brand passion: a moderated moderated-mediation model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:9–102. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S131993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilal FG, Zhang J, Gilal RG, Gilal NG. Linking motivational regulation to brand passion in a moderated model of customer gender and age: an organismic integration theory perspective. Rev Manage Sci. 2018;1–27. doi: 10.1007/s11846-018-0287-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho VT, Wong SS, Lee CH. A tale of passion: linking job passion and cognitive engagement to employee work performance. J Manage Stud. 2011;48(1):26–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00878.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallerand RJ, Houlfort N. Passion at Work. Emerging Perspectives on Values in Organizations. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing; 2003:175–204. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilal FG, Paul J, Gilal NG, Gilal RG. Celebrity endorsement and brand passion among air travelers: theory and evidence. Int J Hosp Manag. In press 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baum JR, Locke EA, Smith KG. A multidimensional model of venture growth. Acad Manage J. 2001;44(2):292–303. doi: 10.5465/3069456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke RJ, Fiksenbaum L. Work motivations, work outcomes, and health: passion versus addiction. J Bus Ethics. 2009;84(2):257–263. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9697-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardon MS. Is passion contagious? The transference of entrepreneurial passion for employees. Hum Res Manage Rev. 2008;18(2):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Zhang J, Yang Z. Associations between a leader’s work passion and an employee’s work passion: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1447–1459. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forest J, Mageau GA, Sarrazin C, Morin EM. “Work is my passion”: the different affective, behavioral, and cognitive consequences of harmonious and obsessive passion toward work. Can J Administrative Sci. 2011;28(1):27–40. doi: 10.1002/cjas.170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vallerand RJ, Salvy SJ, Mageau GA, et al. On the role of passion in performance. J Pers. 2007;75(3):505–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00447.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wrzesniewski A. Finding positive meaning in work. In: Cameron KS, Dutton JE, Quinn RE, editors. Positive organizational scholarship. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler; 2003;296–308. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vallerand RJ. On the psychology of passion: in search of what makes people’s lives most worth living. Can Psychol. 2008;49(1):1.-13. doi: 10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butt HP, Tariq H, Weng Q, Sohail N. I see you in me, and me in you: the moderated mediation crossover model of work passion. Personnel Rev. 2019;48(5):1209–1238. doi: 10.1108/PR-05-2018-0176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moeller J, Dietrich J, Eccles JS, Schneider B. Passionate experiences in adolescence: situational variability and long-term stability. J Res Adolesc. 2017;27(2):344–361. doi: 10.1111/jora.12297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz-Alfonso Z, León J. Passion for math: relationships between teachers’ emphasis on class contents usefulness, motivation, and grades. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2017;51:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL. Primitive emotional contagion. Rev Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;14(1):151–177. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z, Xu H, DU C. The trickle-down effect in leadership research: a review and prospect. Adv Psychol Sci. 2015;23(6):1079–1094. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2015.01079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jillapalli RK, Wilcox JB. Professor brand advocacy: do brand relationships matter? J Mark Educ. 2010;32(3):328–340. doi: 10.1177/0273475310380880 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilal NG, Zhang J, Gilal FG. The four-factor model of product design: scale development and validation. J Prod Brand Manage. 2018;27(6):684–700. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-11-2017-1659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallerand RJ, Blanchard C, Mageau GA, et al. Les passions de l’ame: on obsessive and harmonious passion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(4):756–767. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz-Alfonso Z, León J. The role of passion in education: a systematic review. Educ Res Rev. 2016;19:173–188. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2016.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coleman LJ, Guo A. Exploring children’s passion for learning in six domains. J Educ Gifted. 2013;36(2):155–175. doi: 10.1177/0162353213480432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Day C. The passion of successful leadership. School Leadersh Manage. 2004;24(4):425–437. doi: 10.1080/13632430410001316525 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liston DP, Garrison JW, Eds.. Teaching, Learning, and Loving: Reclaiming Passion in Educational Practice. New York: Routledge Falmer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vallerand RJ. The Psychology of Passion: A Dualistic Model. Series in Positive Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonneville-Roussy A, Lavigne GL, Vallerand RJ. When passion leads to excellence: the case of musicians. Psychol Music. 2011;39(1):123–138. doi: 10.1177/0305735609352441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonneville-Roussy A, Vallerand RJ, Bouffard T. The roles of autonomy support and harmonious and obsessive passions in educational persistence. Learn Individ Differ. 2013;24:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2012.12.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fredricks JA, Alfeld C, Eccles J. Developing and fostering passion in academic and non-academic domains. Gift Child Q. 2010;54(1):18–30. doi: 10.1177/0016986209352683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mageau GA, Vallerand RJ, Charest J, et al. On the development of harmonious and obsessive passion: the role of autonomy support, activity specialization, and identification with the activity. J Pers. 2009;77(3):601–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hobbs L. Examining the aesthetic dimensions of teaching: relationships between teacher knowledge, identity, and passion. Teach Teach Educ. 2012;28(5):718–727. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phelps PH, Benson TR. Teachers with a passion for the profession. Action Teach Educ. 2012;34(1):65–76. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2012.642289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoeber J, Childs JH, Hayward JA, Feast AR. Passion and motivation for studying: predicting academic engagement and burnout in university students. Educ Psychol. 2011;31(4):513–528. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2011.570251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gucciardi DF, Jackson B, Hanton S, Reid M. Motivational correlates of mentally tough behaviours in tennis. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18(1):67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yukhymenko-Lescroart MA, Sharma G. The relationship between faculty members’ passion for work and well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2019;20(3):863–881. doi: 10.1007/s10902-018-9977-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis MR. Perceptual and affective reverberation components. In: Goldstein AP, Michaels GY, editors. Empathy: Development, training, and consequences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1985;62–108. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatfield EC, Bensman L, Thornton PD, Rapson RL. New perspectives on emotional contagion: a review of classic and recent research on facial mimicry and contagion. Interpers Int J Pers Relatsh. 2014;8(2):159–179. doi: 10.5964/ijpr.v8i2.162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howard DJ, Gengler C. Emotional contagion effects on product attitudes. J Consum Res. 2001;28(2):189–201. doi: 10.1086/322897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson SK. Do you feel what I feel? Mood contagion and leadership outcomes. Leadersh Q. 2009;20(5):814–827. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.06.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bono JE, Ilies R. Charisma, positive emotions and mood contagion. Leadersh Q. 2006;17(4):317–334. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fakeye DO. Teachers qualification and subject mastery as predictors of achievement in the english language in Ibarapapa division of Oyo State. Global J Hum Social Sci Res. 2012;12(3):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin SD, Dismuke S. Investigating differences in teacher practices through a complexity theory lens: The influence of teacher education. J Teach Educ. 2018;69(1):22–39. doi: 10.1177/0022487117702573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Connor CM, Son SH, Hindman AH, Morrison FJ. Teacher qualifications, classroom practices, family characteristics, and preschool experience: complex effects on first graders’ vocabulary and early reading outcomes. J Sch Psychol. 2005;43(4):343–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2005.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen DK, Raudenbush SW, Ball DL. Resources, instruction, and research. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2003;25(2):119–142. doi: 10.3102/01623737025002119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baruch Y, Holtom BC. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum Relat. 2008;61(8):1139–1160. doi: 10.1177/0018726708094863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilal FG, Zhang J, Gilal NG, Gilal RG. Integrating self-determined needs into the relationship among product design, willingness-to-pay a premium, and word-of-mouth: a cross-cultural gender-specific study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:227–241. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S161269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilal FG, Zhang J, Gilal NG, Gilal RG. Linking self-determined needs and word of mouth to consumer e-waste disposal behavior: a test of basic psychological needs theory. J Consum Behav. 2019;18(1):12–24. doi: 10.1002/cb.1744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen EL, Bowman ND, Lancaster AL. RU with some1? Using text message experience sampling to examine television co-viewing as a moderator of emotional contagion effects on enjoyment. Mass Commun Soc. 2016;19(2):149–172. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2015.1071400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doherty RW. The emotional contagion scale: a measure of individual differences. J Nonverbal Behav. 1997;21(1):131–154. doi: 10.1023/A:1024956003661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goretzko D, Pham TTH, Bühner M. Exploratory factor analysis: current use, methodological developments, and recommendations for good practice. Curr Psychol. 2019;1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-00300-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osborne JW. Best Practices in Quantitative Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Franke G, Sarstedt M. Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: a comparison of four procedures. Internet Res. 2019;29(3):430–447. doi: 10.1108/IntR-12-2017-0515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther. 2017;98(1):39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayes AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated-moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr. 2018;85(1):4–40. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. London: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gess-Newsome J, Taylor JA, Carlson J, Gardner AL, Wilson CD, Stuhlsatz MA. Teacher pedagogical content knowledge, practice, and student achievement. Int J Sci Educ. 2019;41(7):944–963. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2016.1265158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahn J, Back KJ, Lee CK. A new dualistic approach to brand attitude: the role of passion among integrated resort customers. Int J Hosp Manag. 2019;78:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swimberghe KR, Astakhova M, Wooldridge BR. A new dualistic approach to brand passion: harmonious and obsessive. J Bus Res. 2014;67(12):2657–2665. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Acar IH, Veziroglu-Celik M, Garcia A, et al. The qualities of teacher-child relationships and self-regulation of children at risk in the United States and Turkey: the moderating role of gender. Early Chil Educ J. 2019;47(1):75–84. doi: 10.1007/s10643-018-0893-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shah SR, Udgaonkar US. Influence of gender and age of teachers on teaching: students perspective. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2018;7(1):2436–2441. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2018.701.293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sánchez-Mena A, Martí-Parreño J, Aldás-Manzano J. Teachers’ intention to use educational video games: the moderating role of gender and age. Innovation Educ Teach Int. 2019;56(3):318–329. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2018.1433547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Butler S, Roesel K. The influence of dress on students’ perceptions of teacher characteristics. Clothing Text Res J. 1989;7(3):57–59. doi: 10.1177/0887302X8900700309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang CKJ, Khoo A, Liu WC, Divaharan S. Passion and intrinsic motivation in digital gaming. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11(1):39–45. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gilal FG, Gilal RG, Gilal RG. Romanticism v/s antagonism: battle of minds, a case of beijing pollution. Rom J Multidimension Educ. 2014;6(2):57–78. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gilal FG, Zubaida A, Gilal NG, Gilal RG, Channa NA. Promoting environmental performance through green HRM practices in higher education institutions: a moderated mediation model. Corporate Social Responsibility Environ Manage. 2019;1–12. doi: 10.1002/csr.1835 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang N, Gong ZX, Xu Z, Gilal FG. Ethical climate and service behaviors in nurses: the moderating role of employment type. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:1868–1876. doi: 10.1111/jan.13961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]