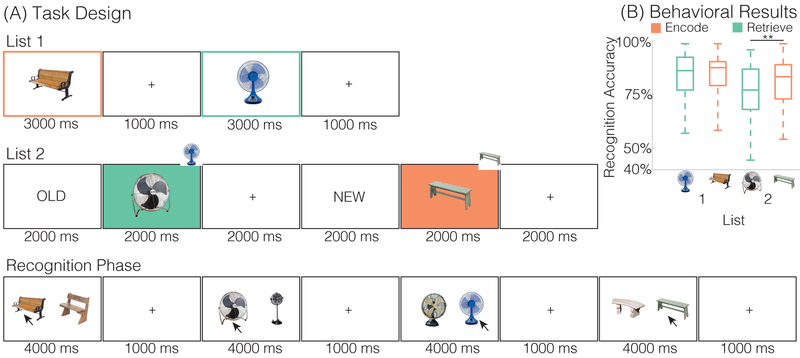

Figure 1. Task Design and Behavioral Results.

(A) During List 1, subjects studied individual objects (e.g. bench, fan). During List 2, subjects saw novel objects that were from the same categories as the items shown in List 1 (e.g., a new bench, a new fan). Preceding each List 2 object was an “OLD” instruction cue or “NEW” instruction cue. The “OLD” cue signaled that subjects were to retrieve the corresponding item from List 1 (e.g., the old fan). The “NEW” cue signaled that subjects were to encode the current item (e.g., the new bench). Colored boxes are shown here for illustrative purposes and were not present during the actual experiment. Each run of the experiment contained a List 1 and List 2; object categories (e.g., bench) were not repeated across runs. After eight runs, subjects completed a two alternative force choice recognition test that tested memory for each List 1 and List 2 object. On each trial, a previously presented object, either from List 1 or List 2, was shown alongside a novel lure from the same category. The subject’s task was to choose the previously presented object. List 1 and List 2 objects were never presented together. (B) Behavioral results. Recognition accuracy is shown separated by list (1,2) and instruction condition (encode, orange; retrieve, teal). There was a significant interaction between list and instruction, primarily driven by greater accuracy for List 2 items presented with an encode instruction relative to a retrieve instruction. Error bars denote SEM; ** p < 0.01.