Abstract

Objective:

Research on employee opinions of workplace wellness programs is limited.

Methods:

At a large academic medical center in Boston, we conducted 12 focus groups on employee perceptions of wellness programs. We analyzed data using the immersion-crystallization approach. Participant mean age (N=109) was 41 years; 89% were female; 54% were White.

Results:

Employees cited prominent barriers to program participation: limited availability; time and marketing; disparities in access; and workplace culture. Encouraging supportive, interpersonal relationships among employees and perceived institutional support for wellness may improve workplace culture and improve participation. Employees suggested changes to physical space, including onsite showers and recommended that a centralized wellness program could create and market initiatives such as competitions and incentives.

Conclusions:

Employees sought measures to address serious constraints on time and space, sometimes toxic interpersonal relationships, and poor communication, aspects of workplaces not typically addressed by wellness efforts.

Keywords: worksite, workplace, health promotion, qualitative research, wellness, obesity, employer, employee, nutrition, exercise, benefits

Introduction

Chronic disease in the US accounted for 7 of the top 10 causes of death in 2014. Heart disease and cancer together were the underlying causes of 46% of deaths.1 People with chronic medical conditions also accounted for 86% of all health care spending in 2010.2 Because full-time, employed Americans spend most of their waking hours at work – an average of 47 hours per week3 – the workplace has evolved as a key setting to promote healthful lifestyles. In 2016, almost half (47%) of American employers, including 46% of small firms and 83% of large firms with over 200 employees, provided some form of a workplace wellness program, with stated goals of improving health and decreasing healthcare costs.4 The breadth of workplace wellness programs varies widely, including (1) individually-focused workplace programs such as nutrition counseling, gym membership reimbursements, health screenings, and wellness competitions, (2) environmental-level changes such as onsite gyms and improvements in the diet quality of offerings at cafeterias, and (3) factors that contribute to healthy workplace cultures and employee satisfaction, such as flexible work hours and programs to promote supportive workplace relationships and decrease interpersonal conflict.

Despite the growing popularity of workplace wellness programs, multiple reviews and meta-analyses of program effectiveness have shown mixed results. A recent randomized clinical trial of almost 33,000 employees at one large US retail company found that employees at worksites with wellness programs reported an 8.3% higher rate of regular exercise and a 13.6% higher rate of actively managing their weight than control participants whose worksites did not have programs; there were no differences in other health behaviors, clinical markers of health, or healthcare spending after 18 months.5 Evaluations of wellness programs at Pepsico and BJC Healthcare found no net savings or positive return on investment (ROI).6,7 A more recent review by McIntyre et al. found that most wellness programs, especially those that focused on lifestyle over chronic disease management, have limited effectiveness.8 In contrast, a meta-analysis by Baicker et al found positive ROIs after 3 years of up to $3.27 for every dollar invested.9 A large RAND study of multiple employers found that programs were associated with decreases in weight and smoking rates, along with increases in physical activity, but no meaningful differences in cholesterol measures or healthcare expenditures.10 Other reviews for wellness programs found high variability in design and quality but concluded that some comprehensive wellness programs improved both health and financial outcomes in the long-term (over three years).11-13 A 2008 US national survey found that less than 7% of employers offer such comprehensive programs,14 defined by the Healthy People 2010 initiative as those that incorporate health education, have supportive environments, are integrated into the organization and linked to other assistance programs, and include workplace health risk screenings.15

Previous research has often only considered employer views on programs (e.g. ROIs, productivity, absenteeism), while research on employee opinions of these programs is limited.16 The sparse research available has found frequent mismatches between employer and employee perceptions of access to programs,16 effects,17 and workplace causes of stress.18 In particular, there has been a recent change in efforts by employers to improve workplace culture instead of only creating programs that focus on healthy behaviors,18 and qualitative research is needed to reveal what employees want from such efforts, as well as what they consider a culture supportive of employee wellness. Workplace culture refers to the shared social norms, values, and attitudes toward employee health; healthy workplace relationships that can facilitate resolving interpersonal conflict; and perceived support of employee wellness from institutional leadership.19 It also is unclear which is more important for employee wellbeing: optimizing wellness offerings by determining the ideal content, frequency, and marketing of programming, or instead focusing on workplace policies and cultures that may promote healthier lifestyles and reduce stress irrespective of wellness offerings. While the ideal workplace wellness program would encompass all these factors, there is no research on how employees prioritize these factors or how these factors may be combined into a comprehensive program.

This qualitative study was conducted at a large academic medical center in Boston to gauge employee perceptions of existing and potential future workplace wellness programs. Hospitals are unique environments because of the emphasis on caregiving and health. They are also diverse work environments where people work in a range of roles from engineering and maintenance to professional and management roles, providing opportunities to explore perceptions across a wide socioeconomic spectrum. A review of the impact of shift work on health outcomes suggested a higher risk of breast cancer for night shift workers, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes for shift workers in general.20 Given the health risks associated with shift work, this qualitative study specifically included vulnerable work groups such as overnight employees and those working in positions such as housekeeping and transport.

Methods

Study Design

Between March and May 2014, we conducted 12 one-hour focus groups with employees of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a large academic medical center in Boston, MA. Seven of the focus groups were open to any employee regardless of team or occupation, two were held at clinical sites away from the main medical center campus, and three were reserved for people who met specific criteria because they were underrepresented in other focus groups: environmental service staff, nurse managers, and overnight shift employees. Each of these three targeted focus groups were homogenous with regards to occupation to promote open discussion. At the time of this qualitative study, wellness opportunities available were varied and not connected under one centralized wellness program. Focus group participants identified the available activities including exercise groups, yoga classes, discounts on gym membership, employee organized contests such as a “Biggest Loser” weight loss program, and general employee assistance programs for mental health services, among others. This study was approved by the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institutional Review Board.

At the beginning of each focus group, participants completed a brief, anonymous questionnaire that included questions about 1) demographics, height, weight, and occupation, 2) participation in current workplace wellness activities, and 3) interest in financial incentive wellness programs.

Two of the investigators (JPB, SKL) facilitated the focus group discussions using an interview guide of open-ended questions designed to capture a wide range of employee perceptions of existing and potential future workplace wellness programming. We asked participants questions about opportunities to pursue healthy behaviors at work, barriers to healthy lifestyles at work, perceptions of their employer’s role in promoting wellness, and their thoughts about the potential use of financial incentives for achieving health outcomes, including weight loss (Box 1). We asked spontaneous follow-up questions to probe participants when necessary. Focus group discussions were audio recorded and professionally transcribed, verbatim.

Box 1: Focus Group Guide.

1. WORKPLACE AS A SITE TO PROMOTE HEALTHY LIFESTYLES

- If a BWH employee wants to try to stay healthy, or to become healthier while at work, how easy would that be?

- If someone wanted to be physically active or get some exercise during the day, how could he/she do it here at the hospital?

- If an employee wanted to eat healthy food, how could he or she do that during their work shift?

- How could your workplace do a better job of promoting a healthy lifestyle?

- What would you like to see more of? Opportunities or facilities for exercise? More healthy foods? Stress reduction programs? Other things?

- What would you like to see less of or changed?

- How do you take advantage of opportunities to be physically active at the workplace?

- Who here makes a point to get some physical activity at some point throughout the day? Let’s see a show of hands. How do you do that?

- What facilities, programs, building features, people, etc make it easier to be active here?

- What factors do you consider when moving throughout the building?

- How do you take advantage of healthy food options at the workplace?

- How many of you buy lunch in the cafeteria at least some days of the week? Let’s see a show of hands. OK, what do you like about buying lunch there? What don’t you like about buying lunch there?

- How do you use the hospital’s vending machines?

- What factors do you consider when purchasing food on or off site?

- Who brings their own food from home at least some days of the week? Let’s see a show of hands. What do you like about bringing your own food? What is challenging about bringing your own food?

- Do people you work with bring in food to share from home? Are there communal areas with food? What kind of food? How often do you eat that? Do you like or dislike when people do this?

Is there anything about BWH policies or environment that makes it difficult for employees to pursue a healthy lifestyle?

- What should be the role of Brigham and Women’s in promoting a healthy lifestyle?

- BWH is your employer and, for many of you, provides you with health insurance. Does their role in promoting a healthy lifestyle differ as your employer versus the company that provides you with health insurance?

- Do you think BWH cares about your health? Why or why not?

- Are there wellness activities that BWH might provide to you (even if they don’t now) that you might consider inappropriate or offensive?

Are there healthy lifestyle choices that you have adopted here at work that you then put into practice outside of work? What?

2. INTERVENTIONS

-

CAFETERIA CHANGES

Now, let’s talk about a health promotion activity that has occurred at your workplace over the last several years. What if any changes have you noticed in the cafeteria?- What are your thoughts about the changes that have been made in the cafeteria?

- Labeling of nutritional content of menu items, using a red, yellow, green labeling system?

- Keeping healthy food items priced low?

- How do you feel about these changes?

- Have any of these changes in the cafeteria made you interested in changing any of your eating behaviors? At work? At home? How so?

-

FINANCIAL INCENTIVE FOR WELLNESS TARGETS

Have you heard about programs where employers offer financial incentives to participate in a wellness program or to meet wellness targets, such as a lower body weight, not smoking, and meeting healthy blood pressure and cholesterol targets?- What would you think about having this kind of program here?

- How do you feel about these specific health targets (weight, smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol)?

- How much should the financial incentive be?

- Should the financial incentive be offered as cash, as part of the paycheck, in some other form? A reduction in your health insurance premium? Credit to your health savings account? Extra vacation days?

-

FINANCIAL INCENTIVE PROGRAM FOR WEIGHT LOSS

What would you think if Brigham offered a voluntary program to promote weight loss or maintenance of weight already lost by allowing you to bet on your own success? You would contribute money every ten weeks and only receive the money back if you meet weekly weight targets. The money would be split in 10 ways. If you meet the weekly weight target, you would receive 1/10 of your money back. If you do not meet the weekly weight target, you would lose that money. Programs like this have been shown to be successful in promoting weight loss.- How would you feel if BWH offered a program like this to its employees?

- Do you think a program like this would work?

- What is it about a program like this that would make it likely to succeed?

- Who would be likely to participate in a program like this?

- Do you know anyone who might participate in a program like this?

- Would you participate in a program like this? Why or why not?

Recruitment

We recruited employees using advertisements in emailed employee newsletters and flyers on bulletin boards throughout the medical center. We conducted focus groups primarily over lunch breaks or other times that suited employee schedules (i.e., in the evening for overnight workers). To encourage participation, we provided a light meal and $25 at the end of each focus group.

Analysis

We analyzed transcript data using principles of immersion-crystallization.21 This qualitative approach entails carefully reading the transcripts to identify themes and patterns.21 Five of the investigators (MWS, PW, SKL, REG, JPB) individually read the transcripts and took notes, followed by analysis team discussions of the data. Next, one investigator (PW) conducted line-by-line coding of the transcripts based on these identified themes and topical categories within the data using Provalis Research QDA Miner,22 a qualitative data management software. Coding facilitated further analysis by topic/theme, and all members of our study team reviewed the coded data to agree upon final themes and interpretation of the data.

Results

The total number of participants in the 12 focus groups was 109 with a range of 3 to 11 participants per group. Mean age was 41 years; 89% were female; and the mean body mass index (BMI), calculated from self-reported heights and weights, was 26.1 kg/m2 (Table 1). The focus groups included more women (89% vs. 70%) and people of minority race/ethnicity (46% vs. 35%) than the general population of Brigham employees. Just over half (54%) self-identified as White, 21% Black, 15% Hispanic, and 9% Asian. In pre-focus group questionnaires, 21% reported current participation in a wellness activity at work, and 87% reported interest in financial incentives for wellness.

Table 1:

Participant characteristics

| Mean Age | 41 years | |

| BMI | 26.1 kg/m2 | |

| % Female | 89% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | % White | 54% |

| % Black | 21% | |

| % Hispanic | 15% | |

| % Asian | 9% | |

| Interested in financial incentives for wellness? | 87% | |

| Wellness activity participation? | 21% | |

In the focus group discussions, several key themes emerged about existing and potential workplace wellness initiatives: 1) Employees appreciate current wellness activities that are available; 2) Various stressors and barriers hinder participation in workplace wellness programming; and 3) Increasing employer support of workplace wellness requires several levels of change, including workplace cultural and physical infrastructure modifications.

Employees appreciate current wellness activities

Employees reported positive experiences with several workplace wellness offerings including exercise classes, walking clubs, and step competitions. The social component of these classes frequently drove participation. One participant stated, “Knowing other people are doing it too and seeing familiar faces and seeing other people participate is just even a little bit more motivating. And it almost helps you make an excuse to do it.” The existence of a program was felt to provide some permission to participate. Having an excuse to participate was important, because generally the fast-paced workplace was not seen as supportive of taking breaks for exercise or other wellness activities (see “Workplace culture not conducive for wellness” section).

Outside of physical activity, employees noted improvements to the cafeteria that came with a food labeling project: “They’re pushing the healthy options more, and instead of fries…ask for a side of vegetables…given the caloric intake. I’ve definitely noticed that. So it does help me make better choices.” This comment referred to a traffic light labeling program that highlighted the dietary quality of menu items (green – highest dietary quality; red – lowest). Appreciation for this program was notable because generally, the unhealthy nature of cafeteria offerings and its physical infrastructure were viewed poorly.

Wellness programs signal that the hospital cares about employees

Although employees appreciated current wellness programming, they hoped for more activities, especially because they viewed these activities as not just providing opportunities for improving diet and physical activity. They described wellness programs as “something that would make me feel that, not that I don’t care for myself, but that somebody else also is invested in my health.” Another employee stated, “We spent so much time taking care of these patients…Dressing them, getting them undressed, talking to them about their health. Do you smoke? What did you eat today? You drinking soda? No one has ever done that for me. Showing same empathy for us as we’re expected to show for our patients.” Employees felt increased wellness offerings were a caring message of support from leadership.

Barriers to workplace wellness

Lack of marketing and availability of wellness programming limits participation

Although employees were aware of some wellness programs, many of the focus group participants were unaware of existing activities. Employees sought more transparency about offerings with centralized information made available to all employees. Employees thought that marketing and communication of programs was limited: “There’s a huge disconnect,” and activities were “not very well publicized.” Employees felt they “get bombarded with so much information,” and that word about wellness activities “doesn’t always trickle to everybody.” Many participants asked, “Where is the big list [of offerings]?” and suggested a “calendar of events” that would allow for employees to view all available activities.

Off-site and overnight employees are missing out

Focus groups for offsite and overnight employees revealed disparities in wellness opportunities compared to those available to main campus, day-shift employees: “I think that being here offsite is a disadvantage to us because I used to work on [the main campus], and I never felt the way I do now.” Many overnight participants expressed similar concern that “The hospital basically runs for first [day] shift only.” Even food options during the night shift were limited: “You don’t even want to really mess with that food because it’s sitting in the burners all day.” The overnight shift was a general barrier to wellness program participation, because of the type of work done and the limitations on staffing: “On nights there’s just not enough of us that we feel comfortable about really leaving [duties] for thirty minutes.”

Not enough time for wellness

Limited schedule flexibility and lack of time commonly emerged as key barriers to wellness. One nurse said they were “at the mercy of the schedule. So we’re lucky we get lunch.” Those who did report breaks during the day often felt they were insufficient to take advantage of them: “Half an hour? That doesn’t do anything. That barely gets you to the bathroom and back.” Other employees agreed, explaining that “You have to get undone, lab coats and gloves and wash and, it takes us [time]; it’s a project.” Employees identified a challenging paradox of wellness programming. Even when available, programming was hard to attend, and access was highly dependent on schedules and availability. As one employee stated, “[I am] really happy the hospital is offering these. We wish though there was some more variety in the timing.”

Workplace culture not conducive for wellness

Employees identified the hospital as a particularly stressful environment. Stress as an underlying concept was consistently mentioned in the context of specific barriers as well as cultural problems or conflicts. Although employees raised logistical time-related concerns, employees identified generalized cultural barriers leading to a perception of lack of support for employee wellness: “One value we don’t show is the valuing of our own health.” Many participants said they felt guilty taking a break to eat lunch, let alone using the break for wellness activities: “It almost seems as a detriment if people do take lunch. Like oh my gosh you’re taking lunch?” Another employee explained that “working out for a lunch break is kind of like a pampering thing.” Employees felt that “It’s not part of the culture,” and that “We’re a hospital. We’re open twenty-four/seven. So we should always be available, always, always, always.” As a result, employees said they would “stuff your [gym] bag underneath your desk so no one sees it,” and some felt the need to “sneak off” to do exercise to avoid judgement. One employee summarized workplace wellness at the hospital: “You’re sending mixed messages. You’re saying you have these programs here. And they’re available to you. And you should do it, but…if they do take you up on that offer they’re frowned upon like ‘are you really going to do that right now?’” Available programming, especially if provided during the day, was unavailable to many employees because of job requirements and lack of flexibility. Employees felt that program participation would require direct or at least the perception of permission from supervisors and recognition by coworkers that wellness activities are acceptable. One participant said, “there’s no managerial push to be healthy,” and others said if “management can be more aware or be supportive for these issues I think it would be better.” Culture barriers were stark for some employees, especially those in housekeeping. They reported a general lack of empowerment and acceptance from other employees. This was exacerbated by a lack of areas to take breaks. They felt this poor treatment was a barrier to rudimentary feelings of inclusion, precluding consideration of more active wellness.

Improving employee health through workplace initiatives requires several levels of change

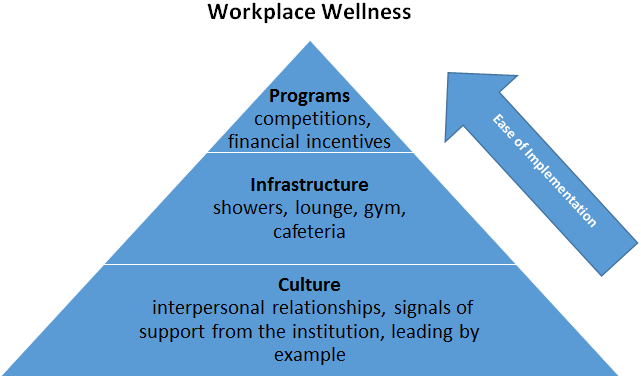

While workplace wellness programs are typically focused on specific activities around nutrition and physical activity, these focus group discussions highlighted that wellness is more than practicing healthy behaviors at work. Employee recommendations for improving workplace wellness included three levels of change starting with improving workplace culture (Figure 1, level 1). Culture consisted of interpersonal relationships with peers and supervisors as well as perceived support of wellness from the institution. Employees recognized that culture would be difficult to change but felt it would have the greatest effect on wellness. The second level of recommended change involved infrastructure improvements such as onsite showers, employee lounges or break areas, onsite gyms, and a better cafeteria as essential to provide and enable participation in wellness opportunities (level 2). Finally, employees suggested that these base levels of support for wellness would set the proper foundation for a centralized wellness program that organized and marketed wellness initiatives such as health screenings and competitions (level 3).

Figure 1:

Employees emphasized that wellness improvements follow levels of change, starting from fundamental relationships with peers and supervisors up to physical spaces and centralized wellness programming.

Culture

Support for wellness must come from the top-down

Employees suggested that department directors and upper level management needed to make wellness a priority with their employees and to encourage middle managers to provide support. In a comment that was echoed by other focus group participants, one person stated: “I think it has to start from the top. If the institution supports it, then I think your boss/supervisor would have no choice but to hopefully [support it].” Employees also emphasized how important it is for management to not only approve of wellness activities but to explicitly encourage employee participation: “If they were to say, hey, these types of activities are okay. Join a walking group. Do the [stair] climbing thing. That would probably push more people to do it.” Participants said that this clear support from management would make them feel less guilty about engaging in wellness programming: “I can go and feel comfortable that I’m there, that I’m allowed to be there and that I’m not neglecting my job.” Employees felt that once higher-level management explicitly approved and supported a healthy workplace culture, it would enable and encourage participation and engagement in wellness activities.

Employer support for grass roots efforts

Employees felt that top-down support of a healthy workplace culture could not only increase utilization of centralized wellness programming but also foster effective grass roots wellness campaigns. Many employees described successful grass roots efforts including departmental walking and stair climbing groups as well as weight-loss and step competitions run by nurses on each floor of the hospital. These informal activities were popular because they were actively organized by participants: “Because we don’t get the chance to participate in whatever Brigham has to offer because of our working hours, the people that we work with have…decided to form a motivation group…that they’re trying to get everybody to join, and…started a Biggest Loser [weight loss] program.”

“Wellness” is more than just improving diet and exercise; it includes improving interpersonal relationships at work

Many employees described wellness as starting with improving sometimes strained interpersonal relationships; employees felt this was a particular need in an intense and stressful hospital workplace: “When I think of [a] healthy work environment…how…we communicate with one another” is key “because when we are in this kind of pressure cooker environment, it does cause people to turn on one another.” One participant described a need for some supervisors to change their communication style: “The way that the supervisor talks to us. I don’t think I even talk to my kids the way he talks to me, to us, you know? This is a problem.” Several employees identified the stressful nature of a healthcare workplace as a reason for notable problems with relationships and communication.

In a targeted focus group of nurse managers, one participant discussed experience confronting particularly toxic relationships. Her department worked with an outside group on conflict resolution and improved communication and management of the group, discussing “principles about when we are in discord with someone, how we look to try and get to a better place.” Without these strategies to promote better interpersonal relationships, the manager stated: “It’s like putting on your earrings or your tie before you figure out what you’re wearing for the day… just so basic to really strategically thinking about ‘how do we communicate with one another?’” Another employee stated: If “we don’t teach people how they might be able to engage with one another in a different way, then we may lose an opportunity to really fully reach our potential.” In a wellness context, this reflects how a supportive workplace culture could form the framework for the more traditional aspects of workplace wellness programs: infrastructure improvements and program offerings (Figure 1).

Brick and Mortar (Infrastructure) and Programs to Support Wellness

Lack of onsite showers are exercise deal breakers

One of the most commonly repeated answers that emerged when we asked participants how they would improve workplace wellness was to provide on-site showers. Many employees said a lack of showers was a major barrier to exercise: “That would be something that is so attractive to me because I could use a part of my day to do more for myself, but I’m a sweater.” Although a few employees had access to showers, they described them as “scary” and in disrepair.

Lack of physical spaces like lounges, gyms, and cafeterias is a major impediment to “wellness”

Providing a dedicated employee-only lounge for breaks and lunch was also a popular recommendation across focus groups. Many employees echoed one participant who wanted a place to “disconnect” from the rest of the hospital during breaks. This was most important for employees who had no areas to take breaks; some employees even felt judged if they took breaks in public areas because they lacked access to private areas to do so. An onsite gym was attractive to employees, though they recognized that adding a gym would be a significant and expensive undertaking for any institution. Employees highlighted that an onsite gym would allow them the benefit of being able to exercise at any time of the day.

Employees said the “whole cafeteria needs to be revamped” including improvements to the physical space of the cafeteria such as better lighting and aesthetics. Employees consistently said cafeteria food was mostly unhealthy and that the cafeteria layout was limiting. Many employees were dissatisfied with the cafeteria food and tried to bring food from home if their departments offered fridge space: “I mean it’s a hospital, but the meals…put you in the hospital.”

Overall support for wellness financial incentives despite some privacy concerns

Focus group participants generally liked the idea of employers giving financial incentives for wellness. Participants said that “Money always talks,” and that incentives “could be the push, the catalyst,” for achieving lifestyle changes. Many employees added that incentives that were part of wellness competitions would be effective. However, a few employees raised privacy concerns about how employers might use health data collected through a financial incentive program, such as one that requires employees to have laboratory and vital sign screenings, with incentives to meet certain health metrics: “I would be very nervous disclosing all my health information if I had like high cholesterol or osteoporosis or any chronic issues. For the hospital to know this is you don’t know how they’re going to use it. It’s like the big brother watching you.” When asked about financial rewards (e.g., reduced premiums for meeting health goals or other monetary incentives) versus financial penalties (e.g. increased premiums for smokers), employees preferred rewards and felt it was important to establish rewards before implementing penalties.

Discussion

In focus groups of healthcare employees from a range of jobs, shifts, and worksites associated with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, we found that employees appreciated current wellness activities, but acknowledged several barriers to participation: 1) limited availability and marketing of wellness programming, 2) disparities in access to wellness opportunities for off-site, overnight, and housekeeping employees, 3) not enough time at work for wellness, and 4) unhealthy workplace culture and relationships with managers. Three major employee recommendations for improving workplace wellness emerged. First, employees strongly advocated for improvements in everyday workplace culture, like help in navigating difficult interpersonal relationships. Employees viewed healthy relationships as foundational for wellness and needed before employees could take full advantage of wellness programming. Supportive work relationships and explicit approval from leadership for employees to prioritize workplace wellness could also increase engagement in centralized wellness programming and help foster grass roots wellness programs. Hospitals could provide grass roots programs with structure- and resource-based support, like marketing and organizational assistance or funding the incentives for participation or engagement. Second, employees wanted greater access to spaces that would facilitate healthy behaviors. This included onsite gyms, more attractive cafeterias, and employee-only lounges where they could unwind. Lack of onsite showers, for example, was viewed as a key barrier to exercising during the day. Of note, after these focus groups were completed, a full-scale renovation of the cafeteria was completed. Third, employees felt a centralized, branded, and organized wellness program was needed to properly market the wellness offerings.

Although prior research on employee perceptions of workplace wellness programs in the US is limited,16 some of the themes that emerged in our analysis are consistent with results from focus groups of university employees, about half of whom participated in a workplace wellness program.23 That study also reported that inconvenient locations, lack of time, and scheduling issues were key barriers, along with insufficient financial incentives to participate.23 Similarly, a study of nurse assistants who participated in a workplace wellness program found that patient care workloads and scheduling issues (e.g. not offering early morning activities before work) were major barriers to participation.24 Our study additionally identified employees’ desire for all traditional wellness programming, such as health education and exercise classes, to be rooted in a supportive workplace culture. Recent surveys on work environment perceptions echoed this sentiment.16 In an analysis of two independent, nationally representative surveys of US employers (N=705) and employees (N=1833) working at least part-time for companies with 50 or more employees, McCleary et al. found that perceptions of a healthful work environment were shaped by both physical spaces (e.g., gyms, healthy food options) and a healthy work culture, and that managers should lead by example and openly participate in workplace wellness programming.16 In our study, employees emphasized how important it is for cultural change to be made from the top-down, and that explicit encouragement from executives and supervisors could mitigate judgement from peers and managers when employees take time during the work day for wellness activities. A process evaluation of a University of California wellness program made similar recommendations that involving leadership at multiple levels, especially among middle managers, was critical to successful implementation.25 Employee perceptions of support from leadership has been shown to be an important determinant of commitment to programs.26 An online study by Jenkins et al. analyzed 10,000 university employee questionnaires on favorable workplace cultures of health and found similar results; the most important factors were leaders and supervisors who demonstrated interest in wellness, as well as having colleagues participate in wellness activities to set good examples.27

Employees in our study also felt that improvements in interpersonal relationships, perhaps promoted by conflict resolution training, would help set the stage for wellness at work. In turn, employees felt improved relations might both reduce stress and encourage colleagues to participate in organized wellness programming. Research at a multinational company found that employees who engaged in workplace conflict resolution reported significantly lower rates of stress, poor general health, and sick time compared to employees who did not report attempting conflict resolution at work.28 Another qualitative study of kitchen and laundry room employees in an Icelandic hospital concluded that supportive work relationships developed employees’ sense of self-worth and belonging, promoting open communication and information exchange.29 Positive interpersonal relationships may reduce stress irrespective of wellness program participation. In another setting, a process evaluation of a university wellness program found that workplaces with good social climates (i.e. abundant social interaction among staff) had more success implementing wellness programs.25 Conflict resolution training could help foster these healthier social climates. Furthermore, collaborative work environments with open communication may encourage employees to not only participate in centralized wellness programming but also provide input and spearhead new grass roots wellness initiatives.

The theory of social capital in health can help explain how workplace culture and interpersonal relationships may improve workplace wellness. Social capital refers to resources accessed by people within a social structure that promote cooperation, collective action, and the maintenance of health behaviors. Growing literature supports the link between social capital and health outcomes.30 In our study, employees felt the social component of wellness programs often drove participation, and explicit support from institutional leaders enabled participation and prevented judgement from peers around taking time during busy work schedules for wellness activites. A study by Kwon et al. analyzed workplace culture in a health care organization and medical equipment company. Using a factor analysis, they found the most beneficial characteristics for culture were also elements of social capital including coworker support, supervisor support, and senior leadership and policies rather than wellness program content and incentive design.31

Limitations

We conducted this study at one academic medical center in Boston, MA. Wellness programming and physical structures of workplaces are typically unique to specific institutions. While results may not be generalizable to other settings, this study provides a more in-depth, contextualized understanding of the employee experience of workplace wellness.32 Because renovations of the cafeteria were completed after focus groups, comments about the cafeteria may not apply to the current physical environment. Although we sought to include nurses, managers, overnight staff, and employees from environmental services, those groups were underrepresented in our focus groups compared to other occupations; no physicians participated. This study also did not include participants from upper-level management such as executives or department chairs, which could benefit future research. Most of the focus groups were open to all occupations. While this maximized the number of participants who could join each session, it is possible that including employees from managerial and non-managerial roles in the same group may have influenced what non-managerial employees were willing to discuss. However, themes regarding a top-down approach were consistent across focus groups, including the three focus groups limited to single occupations or managers.

Conclusions

Considering the recent focus of employers to improve workplace culture rather than wellness program design, our results suggest that institutions should encourage company leaders and middle managers to express explicit support for employees engaging in wellness activities at work and lead by example by participating in these activities themselves. Employees are interested in aspects of workplace wellness outside of traditional programming, such as conflict resolution trainings to improve interpersonal relationships. Employees recognized that changing the culture could be beneficial to their overall wellbeing at work even without measurable improvements in biometrics or financial outcomes. Often employers focus on wellness programming content and incentive design without attention to potentially more impactful factors such as support from managers and coworkers that are elements of social capital. While initiatives to improve support and workplace relationships have not been explicitly tested, the lack of these components in wellness programming may explain how some prior studies have found limited effects of these wellness programs on clinical health outcomes. Employees felt that modifying workplace culture through interpersonal relationships with peers, and perceptions of support from the institution, could improve employee experiences at work and lead to more successful wellness programming. Explicit health improvements and perhaps employer healthcare cost-savings could eventually flow from these initial foundational improvements.

Clinical Significance: Employees felt improving workplace culture could be beneficial to their overall wellbeing at work even without measurable improvements in biometrics or healthcare cost reductions that employers seek. These basic improvements could eventually lay a foundation for centralized wellness programs that lead to improved health and healthcare cost savings.

Acknowledgements:

J. P. Block was supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant number K23HL111211). Funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, or writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHS FastStats - Deaths and Mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm. Accessed June 17, 2017.

- 2.Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D, et al. Multiple Chronic Conditions Chartbook. Rockville, MD; 2014. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/decision/mcc/mccchartbook.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saad L The “40-Hour” Workweek Is Actually Longer -- by Seven Hours. https://news.gallup.com/poll/175286/hour-workweek-actually-longer-seven-hours.aspx. Published 2014. Accessed June 7, 2017.

- 4.Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, et al. Employer Health Benefits. Menlo Park; 2016. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-2016-Annual-Survey. Accessed February 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song Z, Baicker K. Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes. JAMA. 2019;321(15):1491. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caloyeras JP, Liu H, Exum E, Broderick M, Mattke S. Managing manifest diseases, but not health risks, saved pepsico money over seven years. Health Aff. 2014. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gowrisankaran G, Norberg K, Kymes S, et al. A hospital system’s wellness program linked to health plan enrollment cut hospitalizations but not overall costs. Health Aff. 2013. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McIntyre A, Bagley N, Frakt A, Carroll A. The dubious empirical and legal foundations of workplace wellness programs. Health Matrix. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baicker K, Cutler D, Song Z. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Aff. 2010. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattke S, Liu HH, Caloyeras JP, et al. Workplace Wellness Programs Study. RAND Corporation; 2013. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR254.html. Accessed June 7, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goetzel RZ, Henke RM, Tabrizi M, et al. Do workplace health promotion (wellness) programs work? J Occup Environ Med. 2014. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lerner D, Rodday AM, Cohen JT, Rogers WH. A systematic review of the evidence concerning the economic impact of employee-focused health promotion and wellness programs. J Occup Environ Med. 2013. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182728d3c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serxner S, Gold D, Parker K. Financial Impact of Worksite Health Management Programs and Quality of the Evidence In: Rippe JM, ed. Lifestyle Medicine. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2013:1325–1336. http://web.a.ebscohost.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzU0OTI0M19fQU41?sid=ba26b8cd-c8cd-4564-af3f-7d9652a21640@sessionmgr4007&vid=0&format=EB&lpid=lp_Cover-2&rid=0. Accessed February 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linnan L, Bowling M, Childress J, et al. Results of the 2004 National Worksite Health Promotion Survey. Am J Public Health. 2008. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC; 2000. http://www.health.gov/healthypeople/. Accessed June 7, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCleary K, Goetzel RZ, Roemer EC, Berko J, Kent K, De La Torre H. Employer and Employee Opinions about Workplace Health Promotion (Wellness) Programs: Results of the 2015 Harris Poll Nielsen Survey. J Occup Environ Med. 2017. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasson H, Gilbert-Ouimet M, Baril-Gingras G, et al. Implementation of an Organizational-Level Intervention on the Psychosocial Environment of Work. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(1):85–91. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31823ccb2f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willis Towers Watson. 2015/2016 Staying@Work — United States Research Findings.; 2016. https://www.willistowerswatson.com/en/insights/2016/04/2015-2016-staying-at-work-united-states-research-findings. Accessed June 7, 2017.

- 19.Pronk N A workplace culture of health. ACSM’s Heal Fit J. 2010;14(3):36–38. doi: 10.1249/FIT.0b013e3181d9f7b6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X-S, Armstrong MEG, Cairns BJ, Key TJ, Travis RC. Shift work and chronic disease: the epidemiological evidence. Occup Med (Lond). 2011;61(2):78–89. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borkan J Crystallization-Immersion In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 1999:179–194. http://www.uk.sagepub.com/books/Book9279/toc. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Provalis Research QDA Miner Lite – Free Qualitative Data Analysis Software.

- 23.Person AL, Colby SE, Bulova JA, Eubanks JW. Barriers to participation in a worksite wellness program. Nutr Res Pract. 2010. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2010.4.2.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flannery K, Resnick B. Nursing Assistants’ Response to Participation in the Pilot Worksite Heart Health Improvement Project (WHHIP): A Qualitative Study. J Community Health Nurs. 2014. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2014.868737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hopkins JM, Glenn BA, Cole BL, McCarthy W, Yancey A. Implementing organizational physical activity and healthy eating strategies on paid time: Process evaluation of the UCLA WORKING pilot study. Health Educ Res. 2012. doi: 10.1093/her/cys010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neubert MJ, Cady SH. Program commitment: A multi-study longitudinal field investigation of its impact and antecedents. Pers Psychol. 2001;54(2):421–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00098.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins KR, Fakhoury N, Marzec ML, Harlow-Rosentraub KS. Perceptions of a Culture of Health: Implications for Communications and Programming. Health Promot Pract. 2015. doi: 10.1177/1524839914559942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyde M, Jappinen P, Theorell T, Oxenstierna G. Workplace conflict resolution and the health of employees in the Swedish and Finnish units of an industrial company. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(8):2218–2227. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2006.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunnarsdóttir S, Björnsdóttir K. Health promotion in the workplace: The perspective of unskilled workers in a hospital setting. Scand J Caring Sci. 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawachi I, Subramanian IV., Kim D Social Capital and Health.; 2008. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-71311-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon Y, Marzec ML, Edington DW. Development and validity of a scale to measure Workplace Culture of Health. J Occup Environ Med. 2015. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polit DF, Beck CT. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(11):1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]