Abstract

Context:

Preoperative anxiety in surgical patients imposes stress and dissatisfaction. It results in altered neuroendocrine response and various perioperative complications.

Aims:

This study was conducted to determine the changes in anxiety level and need for information about the anesthetic and the surgical procedures at three different time points before surgery and evaluate the correlating factors.

Settings and Design:

A prospective observational study in a university hospital.

Materials and Methods:

Five hundred adults, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Class 1 and 2 patients were included in this study. Level of anxiety and need for information were assessed with the Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale at three time points before the surgery: Evening before surgery in the ward (T1); on the day of surgery, in the preoperative holding area (T2); and in the operating room, after being positioned on the operating table (T3). T-test was applied to compare the mean between two groups, and the Chi-square test for independence of association between two categorical variables. Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test was applied to test the equality of distribution between two groups. Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for one-way analysis for comparing median score, and Friedman test was applied for two-way analysis of comparing score among three time points.

Results:

Total anxiety score recorded was significantly different over the time period (P = 0.023), with an increasing trend over the time. Need for information did not change significantly over time period.

Conclusions:

Preoperative anxiety continues to increase from ward to operation table. The factors responsible are nonmodifiable.

Keywords: Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale, Likert scale for scoring, preoperative anxiety

INTRODUCTION

Preoperative anxiety has been identified as a leading cardiovascular risk factor in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.[1,2] It has also been shown that high preoperative anxiety levels are related to an altered neuroendocrine response which might be deleterious in the postoperative period.[3,4] A strong correlation between preoperative anxiety-depression and later dissatisfaction of the surgical outcome has also been found.[5] Anesthetic challenges on account of preoperative anxiety include difficult venous access, delayed jaw relaxation and coughing during induction of anesthesia, intraoperative autonomic fluctuations along with increased pain, and nausea and vomiting in the postoperative period.[6,7] There are also increased anesthetic requirement, prolonged recovery, and prolonged hospital stays.

There exists variation in the literature in the reported prevalence of preoperative anxiety and the time of maximum anxiety before surgery in different parts of the world.[6] The reported incidence of preoperative anxiety ranges from 60% to 92% in unselected surgical patients and also varies among different surgical groups.[8] A previous report had suggested the incidence of preoperative anxiety to range from 11% to 80% in adult patients[9] Hence, it would be interesting to look for variability in patients’ anxiety levels at various time points before surgery and determine the correlating factors in our patients. The outcome will also help us in the assessment of our current premedication practices and if there is a need for better preoperative communication with our patients.

Anxiety is a subjective phenomenon, and many instruments are available to measure preoperative anxiety. The Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) was developed, particularly for the preoperative patients, measures anxiety level, and need for information about surgery and anesthesia.[1] This study was designed to evaluate and quantify anxiety in patients scheduled for surgery based on the APAIS scoring.

The primary outcome of this study was to determine the changes in anxiety level and need for information about anesthesia and surgery among the patients at three different time points preoperatively; evening before the surgery, in the ward (T1); on the day of surgery, in the preoperative holding area (T2); and in the operating room, after being positioned on the operating table (T3). The secondary outcome included analyzing the variables that can affect anxiety: age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status, level of education, profession, residential background, substance abuse, history of previous surgery, serial number on the operation list, and season of surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Institute Ethics Committee and registering the trial. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients before enrolment.

This prospective observational study was carried out between April 2016 and March 2017. Consecutive patients admitted for routine gastrointestinal and urological surgical procedures under general anesthesia, who were willing to participate and fulfilled the inclusion criteria were enrolled. One hundred and twenty-five patients were enrolled in each season, namely, winter (December/January), spring (February/March), summer (April/May), and rains (June/July).

Patients of the ASA Physical Status Class 1 and 2 of either sex, ≥18 years of age, who were able to comprehend and willing to participate and admitted at least 1 day before the scheduled surgical procedures were included in the study. Patients with any psychiatric diseases or mental retardation; patients taking anti-anxiety, antidepressant, or sedative medications; patients suffering from any malignant condition; and patient refusal were excluded.

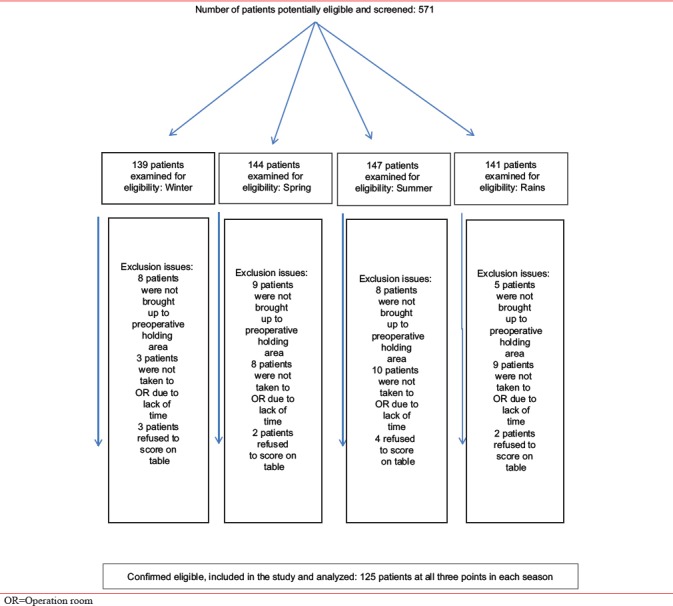

Power Analysis and Sample Size System software (Version 11; NCSS, Utah, USA) was used for calculation of sample size, and Willis Lambda formula was used with results (total anxiety score) of prior studies. With the power of study 90% and alpha error 5%, the sample size came to 321. To remove the clustering effect, design effect 1.5 was taken. Thus, the sample increased to 480. Twenty more patients were added, and a total of 500 patients were recruited for the study that included 125 patients in each season. A patient was considered drop out if the scheduled surgery was cancelled for whatever reason. Drop out patients were replaced with new recruitments to complete 125 patients in each season [Table 1].

Table 1.

Strobe diagram showing patient recruitment

Patients underwent routine preoperative counseling in the outpatient department by the surgeon and in the preanesthetic clinic by another anesthesiologist as per the institute protocol.

Each patient was asked to read the APAIS questionnaire consisting of six questions, translated into local language Hindi.

I am worried about the anesthetic

The anesthetic is on my mind continually

I would like to know as much as possible about the anesthetic

I am worried about the procedure

The procedure is on my mind continually

I would like to know as much as possible about the procedure.

The measure of agreement with these statements was graded on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely. The patients were asked to put tick (√) mark where appropriate and sign the consent form. No further counseling was done with the patients during this process. The patients received oral alprazolam 0.25 mg and ranitidine 150 mg at bedtime on the night before the surgery.

Outcome parameters:

Total anxiety score = sum of responses of items 1, 2, 4, and 5

Anesthesia-related anxiety score = sum of responses of items 1 and 2

Surgery-related anxiety score = sum of responses of items 4 and 5

Need for information score = sum of responses of items 3 and 6.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Stata Version 10 (StataCorp, Texas, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean (95% confidence interval) and ordinal variables with median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were expressed as percentage. Normality conditions were checked for all variables for applying proper test of significance. Most of the outcome variables were ordinal in nature which was measured in score. T-test was applied to compare the means between two groups assuming equal and unknown variance. Chi-square test was applied to test the independence of association between two categorical variables. Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test was applied to test the equality of distribution between two groups. Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for one-way analysis for comparing median score among three time points. Friedman test was applied for two-way analysis of comparing score among three time points by specific covariables.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients by gender are shown in Table 2. A total of 500 patients were enrolled over the study period during four seasons and the distribution of the patients over the season were not significantly different with respect to gender (P = 0.682). The mean age difference of males and females was not statistically significant (P = 0.2952). Age was stratified in two groups, ≥30 years and ≤30 years, to compare the effect of age on total anxiety score. The distribution of age group by gender was not found statistically significant (P = 0.668).

Table 2.

Sex-wise sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | Male (282) | Female (218) | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.99 (35.4-38.6) | 35.78 (34.2-37.4) | t-statistic=1.04 | 0.2952 |

| >30 | 171 | 127 | 0.183 | 0.668 |

| ≤30 | 111 | 91 | ||

| Season | ||||

| Summer | 75 | 50 | 1.5144 | 0.682 |

| Rainy | 71 | 54 | ||

| Winter | 66 | 59 | ||

| Spring | 70 | 55 | ||

| ASA status | ||||

| 1 (%) | 251 (89.4) | 209 (96) | 7.18 | 0.005 |

| 2 | 31 | 9 | ||

| Level of education | ||||

| Illiterate | 89 | 96 | 7.96 | 0.005 |

| Literate (%) | 193 (68) | 122 (56) | ||

| Profession | ||||

| Student | 52 | 18 | 370.05 | 0.0001 |

| Homemaker | 0 | 182 | ||

| Government | 26 | 11 | ||

| Private | 204 | 7 | ||

| Habitat | ||||

| Rural (%) | 231 (82) | 175 (80) | 0.1488 | 0.700 |

| Urban | 51 | 43 | ||

| Substance abuse | ||||

| Yes (%) | 151 (53.5) | 2 (0.005) | 162.53 | 0.0001 |

| No | 131 | 216 | ||

| History of previous surgery | ||||

| Yes (%) | 90 (31.5) | 126 (58) | 35.14 | 0.0001 |

| No | 192 | 92 | ||

| Surgical order | ||||

| 1 | 87 | 77 | 4.371 | 0.358 |

| 2 | 117 | 91 | ||

| 3 | 64 | 38 | ||

| 4 | 12 | 12 | ||

| 5 | 2 | 0 |

ASA=American Society of Anesthesiologists

Nearly, 92% of the patients were having ASA class 1 Physical Status with significantly higher proportion in females compared to males (P = 0.005). As far as the educational status was concerned, the proportion of literates was nearly 62.5% with significantly higher proportion in males (68%) compared to females (56%) (P = 0.005). Nearly 81.5% of males were employed either in government service or private service as compared to only 8.25% of females (P = 0.001).

Nearly 80% of the patients were from rural areas. The habit of substance abuse was significantly higher among males (53.5%) compared to almost null among females (P = 0.0001). The number of patients who had a history of previous surgery was significantly higher among females (58%) compared to males (31.5%) (P = 0.0001). The distribution of surgical order was statistically similar in both genders (P = 0.358).

Except total anxiety score, none of the other scores observed at three different time points were found to be significantly different over the time period. However, total anxiety score recorded was significantly different over the time period (P = 0.023), with an increasing trend over the time [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of anesthesia-related anxiety, surgery-associated anxiety, need for information score, and total anxiety score at three time points

| Variables | Median (IQR) | P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| Anesthesia-related anxiety score | 5 (2-8) | 5 (2-8) | 6 (2-8) | 0.89 |

| Surgery-related anxiety score | 8 (5-8) | 8 (5-8) | 8 (5-8) | 0.99 |

| Need for information score | 5 (2-8) | 5 (2-8) | 5 (2-8) | 0.99 |

| Total anxiety score | 10 (7-15) | 13 (7-16) | 14 (9-16) | 0.023 |

*Kruskal-Wallis test. IQR=Interquartile range

Factors associated with total anxiety score were recorded at three time points [Table 4]. Median of total anxiety score was significantly higher among females at each time point, i.e., at T1 (P = 0.001), T2 (P = 0.001), and T3 (P = 0.001), as well as among the three time points (P = 0.0011) indicating higher level of anxiety among females compared to males. Anxiety score observed was not statistically different between two age groups at each time point; however, the score was significantly different over time period with an increasing trend (P = 0.001). Anxiety score was found to be associated with seasons and an increasing trend was observed over time period in all season (P = 0.001) and lowest score was reported during winter season as compared to other seasons. Patients having ASA Status Class 2 reported to have higher total anxiety score compared to Status Class 1 over the time with an increasing trend (P = 0.001) but was not statistically different within each time point between the two (P > 0.05). Educational status was found to be significantly associated with anxiety score over the time (P = 0.001) indicating higher level of anxiety level among illiterates compared to literates, and also within T2 (P = 0.045) and T3 (P = 0.005). Place of residence was not found to be associated with anxiety score at all-time points (P = 0.89). Total anxiety score was observed to be significantly lower among those who had reported habit of substance abuse at each time point and over the three time point (P = 0.013). There was a significant higher total anxiety score among those patients having the previous history of surgery over the three time points with maximum recorded at T3 (P = 0.044). Surgical order was not found to be significantly associated with anxiety score within each time point, but the anxiety score showed an increasing trend over time (P = 0.001).

Table 4.

Factors associated with total anxiety score at three time points

| Factors (n) | Median (IQR) | P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male (282) | 8 (4-12) | 10 (5-16) | 10 (5-16) | 0.0011 |

| Female (218) | 12 (9-16) | 16 (11-16) | 16 (13-18) | |

| P† | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| >30 (298) | 10 (7-14) | 13 (7-16) | 14 (8-16) | 0.0001 |

| ≤30 (202) | 10 (7-15) | 14 (7-16) | 16 (10-16) | |

| P† | 0.864 | 0.136 | 0.335 | |

| Season | ||||

| Summer (125) | 10 (7-16) | 13 (7-16) | 16 (10-18) | 0.001 |

| Rainy (125) | 9 (7-16) | 14 (10-16) | 15 (10-16) | |

| Winter (125) | 11 (7-16) | 12 (7-16) | 13 (7-16) | |

| Spring (125) | 11 (4-16) | 16 (10-16) | 16 (10-16) | |

| P† | - | - | - | |

| ASA status | ||||

| Grade 1 (460) | 10 (7-14) | 13 (7-16) | 14 (9-16) | 0.001 |

| Grade 2 (40) | 10 (6-16) | 16 (7-16) | 16 (7-16) | |

| P† | 0.8199 | 0.523 | 0.875 | |

| Level of education | ||||

| Illiterate (185) | 10 (7-16) | 14 (8-16) | 16 (10-16) | 0.001 |

| Literate (315) | 10 (6-14) | 12 (7-16) | 13 (8-16) | |

| P† | 0.712 | 0.045 | 0.005 | |

| Habitat | ||||

| Rural (406) | 10 (7-15) | 13 (7-16) | 14 (9-16) | 0.89 |

| Urban (94) | 10 (7-14) | 12 (7-12) | 13 (9-16) | |

| P† | 0.765 | 0.889 | 0.955 | |

| Substance abuse | ||||

| Yes (153) | 8 (4-13) | 10 (5-16) | 11 (7-16) | 0.013 |

| No (347) | 10 (7-16) | 14 (10-16) | 16 (10-17) | |

| P† | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| History of previous surgery | ||||

| Yes (216) | 10 (7-16) | 13 (9-16) | 16 (10-16) | 0.044 |

| No (284) | 10 (7-14) | 12 (7-16) | 13 (8-16) | |

| P† | 0.170 | 0.165 | 0.046 | |

| Surgical order | ||||

| 1 (164) | 9 (6-14) | 13 (8-16) | 13 (9-16) | 0.001 |

| 2 (208) | 10 (7-16) | 13 (7-16) | 16 (10-16) | |

| 3 (102) | 10 (7-16) | 13 (7-16) | 13 (7-16) | |

| 4 (24) | 12 (8-16) | 16 (9-16) | 16 (10-19) | |

| 5 (2) | 9 (7-11) | 8 (4-11) | 8 (4-13) | |

*P: Friedman two-way analysis, †P: Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon U-test between two groups. ASA=American Society of Anesthesiologists, IQR=Interquartile range

DISCUSSION

In our study, in spite of the usual counseling and anxiolytic premedication, anxiety related to anesthesia and surgery significantly increased as patients moved from ward to preoperative holding area and the operation room. In spite of increasing anxiety scores, the need for information did not increase significantly in our patients.

In a study conducted in the Nepalese population, patients aged below 30 years were an independent factor for need to seek information about surgery and anesthesia in the preoperative period.[6] Anxiety scores in different age groups (below 30 years and 30 years and above) at different time points in our study were not significantly different. Our finding was similar to that of Moerman et al.[10]

ASA Physical Status Class 2 patients showed higher total anxiety score with an increasing trend over time. Caumo et al. had found more anxious patients among those who belonged to ASA Physical Status Class 3.[11]

The total anxiety scores were significantly lower in males as compared to females at all three time points. Similar findings were observed in other studies where high anxiety level correlated with female gender.[3,6,10,11] This has been attributed to the fluctuating levels of estrogen and progesterone in females.[12] This difference may also be attributed to the difference between men and women in admitting and reporting their anxiety, rather than for differences in innate levels of anxiety.

Patients with previous exposure to surgical intervention appeared more anxious and wished for more information at all-time points. Their anxiety scores increased significantly on the operation table. Pokharel et al. have reported that patients with no previous exposure to surgery showed more need for information in the ward.[6] Contradictory results have been published regarding the association between previous exposure to anesthesia/surgery and preoperative anxiety with higher[13] and lower[11,14,15] incidence and/or frequency of anxiety. It has been argued that perioperative period may present many unconditioned fear stimuli. Patient's previous exposure may either exacerbate or attenuate fear conditioning, depending on the previous experience. This may explain these varied results.

Majority of our patients belonged to rural area and get admitted to the ward a few days before the day of surgery. It is possible that interaction with fellow patients and their relatives might have contributed in gathering information regarding the procedures during this waiting period to resolve their curiosity.[6] There was no significant difference between the anxiety levels of patients posted at different positions in the operation list, although it did show an increasing trend over time. Our results are similar to that of Pokharel et al.[6] However, others have reported that a long wait in the preoperative holding area and late placement on the operation list also contribute to preoperative anxiety.[14,16]

Both anesthesia and surgery-related anxiety scores were significantly higher in patients with no history of substance abuse. Some studies have found a positive correlation between smoking and a high level of anxiety,[11,14] whereas others concluded that nonsmokers were more anxious before surgery.[13]

Our study revealed that educational status of patients was significantly associated with anxiety, indicating higher level of anxiety among illiterates. It has been argued that a better-educated person can appreciate the risks in a better way and also can express his apprehensions in a better manner.[11] Others have found positive correlation between higher educational status and more need for information.[6] Some studies concluded that patients with low level of education exhibited more anxiety,[3,13] whereas others have found opposite results.[11]

The impact of seasonal variation on the anxiety scores and the need for information score was found to be variable. An increasing trend was observed over time in all seasons. The lowest anxiety score was reported during winter. There is a belief among the rural masses in this part of the world to get routine surgery done during winter months. The lower anxiety levels may be a reflection of this belief.

A study evaluating the relationship between mood and weather in general population had concluded that mood scores on the depression and anxiety scales were not predicted by any weather.[17] However, they observed that anxiety decreased when the number of hours of sunshine increased and the temperature rose, whereas it increased with rain or snow. Another study showed different trends for panic and nonpanic anxiety. Panic anxiety was found to be more during warm winds and autumn months. Nonpanic anxiety exhibited autumn and summer seasonality.[18] These studies are not from our country and may show different values that may not be a reflection of the Indian population.

The need for information did not show an increasing trend. This may be indicative of a satisfactory routine preoperative counseling performed. This result is unlike the study conducted in Nepalese patients where median scores in the need for information scale started decreasing as the patients moved from ward to preoperative holding area.[6] Oldman et al. reported that 65% of their patients did not wish to receive detailed anesthetic drug information.[19] Other have found that patients who were more anxious wanted more information about anesthesia and surgery.[6,10,20,21]

Sensitivity toward patients’ preoperative concerns and anxiety and proactively addressing them is of paramount importance in patient care. Identifying patients prone to anxiety can be difficult, however. People have been classified into “monitors” and “blunters” depending on their ability to cope with a stressful situation.[22] Monitors are people who want to know as much as possible and a lack of information may increase their anxiety. Blunters have no need for information, try to avoid it, and detailed information increases their anxiety. Based on the contradictory observations of different studies including ours, we suggest that rather than adopting a uniform counseling and sedation protocol, we should aim at identifying the monitors and blunters to achieve a better patient care.

There were a few limitations of our study. The patients were counseled preoperatively both by the surgeon and the anesthesiologists. They were also provided with anxiolytic premedication. These factors may have masked the exact levels of anxiety. Furthermore, due to the lower level of education of patients belonging to a rural class, occasionally, we had to help them understand the questionnaire rather than let them fill up them spontaneously. Other limitations of this study included nonuniform interval between different time points of filling up the questionnaire and the fact that these findings cannot be extrapolated to patients admitted on the same day for day care procedures. Validation studies are required before a survey is translated into a language and used in nations using that language. Lack of availability of a validation study of APAIS in local language was another limitation of the study.

CONCLUSIONS

Preoperative anxiety continues to be a problem in our patient population. Anxiety related to anesthesia and surgery significantly increased as patients moved from the ward to the operation room. However, the need for information scores regarding anesthesia and surgery between different time points did not change significantly.

Patient's age, ASA status, and position in operation list did not influence the anxiety and need for information scores in our study. Gender, history of previous surgery, history of substance abuse, educational status, and change in season can influence preoperative anxiety at different time points.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caumo W, Ferreira MB. Perioperative anxiety: Psychobiology and effects in postoperative recovery. Pain Clin. 2003;15:87–101. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarro-García MA, Marín-Fernández B, de Carlos-Alegre V, Martínez-Oroz A, Martorell-Gurucharri A, Ordoñez-Ortigosa E, et al. Preoperative mood disorders in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: Risk factors and postoperative morbidity in the intensive care unit. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2011;64:1005–10. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ai AL, Kronfol Z, Seymour E, Bolling SF. Effects of mood state and psychosocial functioning on plasma interleukin-6 in adult patients before cardiac surgery. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35:363–76. doi: 10.2190/2ELG-RDUN-X6TU-FGC8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson S, Maddern GJ, Fitridge R. The role of pre-operative state-anxiety in the determination of intra-operative neuroendocrine responses and recovery. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10:299–310. doi: 10.1348/135910705X26957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali A, Lindstrand A, Sundberg M, Flivik G. Preoperative anxiety and depression correlates with dissatisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of 186 patients, with 4-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:767–70. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pokharel K, Bhattarai B, Tripathi M, Khatiwada S, Subedi A. Nepalese patients’ anxiety and concerns before surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2011;23:372–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikumb VB, Banerjee A, Kaur G, Chaudhury S. Impact of doctor-patient communication on preoperative anxiety: Study at industrial township, Pimpri, Pune. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18:19–21. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.57852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perks A, Chakravarti S, Manninen P. Preoperative anxiety in neurosurgical patients. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2009;21:127–30. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31819a6ca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maranets I, Kain ZN. Preoperative anxiety and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1346–51. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199912000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moerman N, van Dam FS, Muller MJ, Oosting H. The Amsterdam preoperative anxiety and information scale (APAIS) Anesth Analg. 1996;82:445–51. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caumo W, Schmidt AP, Schneider CN, Bergmann J, Iwamoto CW, Bandeira D, et al. Risk factors for preoperative anxiety in adults. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:298–307. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045003298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstock LS. Gender differences in the presentation and management of social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 9):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinar G, Kurt A, Gungor T. The efficacy of preopoerative instruction in reducing anxiety following gyneoncological surgery: A case control study. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:38. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr E, Brockbank K, Allen S, Strike P. Patterns and frequency of anxiety in women undergoing gynaecological surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:341–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caumo W, Broenstrub JC, Fialho L, Petry SM, Brathwait O, Bandeira D, et al. Risk factors for postoperative anxiety in children. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:782–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panda N, Bajaj A, Pershad D, Yaddanapudi LN, Chari P. Pre-operative anxiety. Effect of early or late position on the operating list. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:344–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1996.tb07745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howarth E, Hoffman MS. A multidimensional approach to the relationship between mood and weather. Br J Psychol. 1984;75:15–23. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1984.tb02785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulbena A, Sperry L, Pailhez G, Cunillera J. Panic attacks: Weather and season sensitivity. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61:129. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oldman M, Moore D, Collins S. Drug patient information leaflets in anaesthesia: Effect on anxiety and patient satisfaction. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:854–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norris W, Baird WL. Pre-operative anxiety: A study of the incidence and aetiology. Br J Anaesth. 1967;39:503–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/39.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kindler CH, Harms C, Amsler F, Ihde-Scholl T, Scheidegger D. The visual analog scale allows effective measurement of preoperative anxiety and detection of patients’ anesthetic concerns. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:706–12. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller SM. Monitoring and blunting: Validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threat. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52:345–53. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]