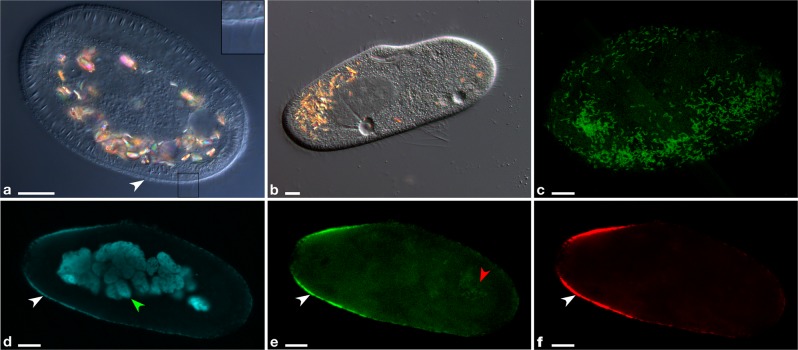

Fig. 1.

Microscopy images of P. primaurelia CyL4-1 covered by extracellular Deianiraea bacteria (a, c–f) and of control uninfected host cells (b). a Differential interference contrast (DIC) of a heavily infected CyL4-1 cell, displaying an atypical shortened and ovoid shape. The Paramecium cell surface is covered by a bacterial multilayer (white arrowhead). As shown in the enlarged inset on the right (corresponding to the square in the main picture) the ciliature is highly reduced, with only few remnants. b DIC picture of control uninfected host cells. c Fluorescence in situ hybridisation microscopy image of the surface of a Deianiraea-covered CyL4-1 cell. Deianiraea cells are visible by the green signal of the FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate)-labelled universal bacterial probe EUB338 [103]. d–f Multichannel microscopy images showing a transversal plan from a FISH experiment on a CyL4-1 cell at an advanced stage of invasion by the putative parasite. In (d) the blue signal from DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) highlights the Paramecium fragmented macronucleus in autogamy (green arrowhead) and the bacterial cells. In (e) the green signal of FITC-labelled EUB338 is shown; in (f) the red signal of the Deianiraea-specific probe Deia_416 labelled with Cy3. In (d–f), the Deianiraea cells covering the external surface of the host cell on its outline are fluorescently stained (white arrowheads). In (e), food bacteria in a digestive vacuole are also visible (red arrowhead), without any corresponding signal from the specific probe in (f). Bars stand for 10 μm