Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has been revealed to be involved in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. However, the mechanism remains to be fully elucidated. Smad-interacting protein 1 (SIP1) is a transcriptional repressor, which serves a pivotal role in cell metastasis. In the present study, the role of SIP1 in HBx-induced hepatocyte EMT and cancer aggressiveness was examined. It was found that HBV X protein (HBx) increased the expression of SIP1 and recruited it to the promoter of E-cadherin, resulting in depression of the transcription of E-cadherin. Histone deacetylase 1 was also found to be involved in the repressive complex formation. Furthermore, in an orthotopic tumor transplantation model in vivo, HBx promoted tumor growth and metastasis, whereas the knockdown of SIP1 attenuated the effect of HBx. These results indicate a novel mechanism for the development of HBV-related liver cancer.

Keywords: liver cancer, Smad-interacting protein 1, hepatitis B virus, epithelial-mesenchymal transition

Introduction

Liver cancer is a prevalent type of cancer in humans that ranks as the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (1). Epidemiological studies have shown that chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major risk factor for liver cancer (2). As a member of the hepadnaviridae family, HBV is among the smallest of all known animal viruses. The integrated hepatitis B virion is a spherical particle, 42 nm in diameter, which is also known as the Dane particle (3). The HBV genome is a circular, partially double-stranded DNA of ~3,200 base pairs. Four overlapping open reading frames encode a viral envelope protein (pre-S1/pre-S2/S), a core protein (pre-C/C), a viral polymerase (P) and an HBV X protein (HBx) (4,5).

HBx, which is highly conserved within the species, is named after the encoding X gene as the amino acid sequence is not homologous to any known protein (6,7). It has been reported to be involved in the etiology of liver cancer through the transcriptional regulation of certain proto-oncogenes. However, the molecular mechanism underlying HBx-induced carcinogenesis remains to be fully elucidated. HBx affects hepatocyte proliferation and transformation by modulating signal transduction, such as the Wnt pathway. As a Wnt-regulated protein, E-cadherin is observed to decrease during epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and has been regarded as the most important factor in the progression of cancer to a more aggressive phenotype. Smad-interacting protein 1 (SIP1) is one of the most important transcriptional regulators for the expression of E-cadherin. In our previous study, it was found that SIP1 regulated HBV replication and expression (8); however, whether SIP1 is involved in HBV-related diseases has received limited attention.

In the present study, the role of SIP1 in HBx-induced hepatocyte EMT and cancer aggressiveness was examined. It was found that the exogenous expression of HBx resulted in hepatocyte EMT through interacting with SIP1. HBx combined with SIP1 and enhanced its ability to bind the promoter region of E-cadherin and repress its transcription. Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) was also found to be involved in the repressive complex formation. Functional analysis demonstrated that the knockdown of SIP1 abrogated the effect of HBx on cell proliferation, migration and tumor aggressiveness. The present study is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to elaborate on the role of SIP1 in HBx-induced EMT and tumor aggressiveness.

Materials and methods

Plasmid DNA and lentivirus

The pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1- HBx (pHBx) plasmids were prepared in the Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology of Infectious Diseases (Chinese Ministry of Education, Chongqing Medical University). The plasmid expressing SIP1 (pcDNA4his/maxC-SIP1) was donated by Professor Janet E. Mertz (McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health). SIP1 short hairpin RNA (shSIP1) or non-targeting shRNA (shCont) were cloned into the pGMLV-SC5 plasmid vector provided by Genomeditech (Shanghai, China). The sequence of the SIP1-targeting shRNA was 5′-GAA CAG ACA GGC TTA CGG A-3′ and that of the shCont sequence was 5′-TGT TCT CCG AAC GTG TGT CAC GT-3′. The plasmids expressing shSIP or shCont were also packaged into a lentivirus. The pGL3-Basic and pRL-TK plasmids were obtained from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI, USA, cat. no. E1751). The wild-type E-cadherin promoter (proE-cad-Luc) and the mutagenic E-cadherin promoter combined with a luciferase reporter (proE-cad-Luc-mEbox) were provided by Kumiko UiTei. The mutation sites of the E-cadherin promoter sequence covered the putative E-boxes between CAG GTG/CAC CTG and AAG GTA/AAC CTA.

Cell culture and transfection

The HepG2 cells were maintained in Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology of Infectious Diseases (Chinese Ministry of Education, Chongqing Medical University). HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin at 37°C under 5% CO2. The hepatoma cell line stably expressing HBx protein was established by transfecting the pcDNA3.1-HBx plasmid into HepG2 cells (at ~70% confluence) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After 24 h, cells were selected with 1,000 µg/ml of G418 sulfate using the limiting dilution method. The cell line was named HepG2-X and confirmed by western blotting. For the transient expression of HBx, the HepG2 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-HBx and were collected after 48 h.

Synthesis of small interfering (si)RNAs

The siRNAs targeting the HBx gene (siHBx) were designed against the conserved target region of the gene. Negative control siRNAs (siCont) were designed with scrambled sequences. All siRNAs were chemically synthesized by Genepharma (Shanghai, China) and the sequences are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Primer and siRNA sequences.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| siRNA | |

| HBx siRNA sense | AAGAGGACUCUUGGACUCUCAdTdT |

| HBx siRNA antisense | UGAGAGUCCAAGAGUCCUCUUdTdT |

| Control siRNA sense | UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUdTdT |

| Control siRNA antisense | ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAAdTdT |

| Chromatin immunoprecipitation | |

| Primer 1 forward | AGGCAGGTGGATCATCTGAG |

| Primer 1 reverse | TGTTCTTGGCTCACTGCAAC |

| Primer 2 forward | TAGAGGGTCACCGCGTCTAT |

| Primer 2 reverse | TCACAGGTGCTTTGCAGTTC |

| PCR | |

| E-cadherin forward | TGCCCAGAAAATGAAAAAGG |

| E-cadherin reverse | GTGTATGTGGCAATGCGTTC |

| Vimentin forward | GCCAGGCAAAGCAGGAGT |

| Vimentin reverse | GGGTATCAACCAGAGGGAGT |

| SIP1 forward | ATGGGGCCAGAAGCCACGAT |

| SIP1 reverse | GTCGACTGCATGACCATCGC |

| β-actin forward | CTCTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCCT |

| β-actin reverse | AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG |

Reagents and antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used in the present study: Rabbit anti-E-cadherin monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA, USA; cat. no. 3195), rabbit anti-N-cadherin monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 4061P), rabbit anti-Slug monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 9585P), mouse anti-vimentin monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA; cat. no. sc-15393), mouse anti-SIP1 monoclonal antibody (E-11; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; cat. no. sc-271984), rabbit anti-SIP1 monoclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK; cat. no. ab-138222), mouse anti-HBx polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; cat. no. sc-57760), mouse anti-HDAC1 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; cat. no. sc-81598), rabbit anti-HDAC1 monoclonal antibody (GeneTex, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA; cat. no. GTX100513222) and mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China; cat. no. BM0627). The HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany; cat. no. T1952). DAPI (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were used according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Western blotting

Protein was extracted from the cells using a protein extraction kit (KaiJi, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The protein concentration was measured with BCA protein assay reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Approximately 50 µg of protein was separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and blotted onto PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). After being blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h and blotted with the indicated primary antibodies (anti-E-cadherin, anti-N-cadherin, anti-vimentin, anti-SIP1 and anti-HDAC1 at 1:1,000 dilution; anti-Slug and anti-HBx at 1:500 dilution; anti-β-actin at 1:2,000 dilution) on a shaker at 4°C overnight, the membranes were incubated with secondary goat anti-mouse antibody (1:5,000 dilution Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China; cat. no. BA1050) or goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:5,000 dilution; Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China; cat. no. BM1054) for 1.5 h at 37°C. The levels of targeted protein in the cells were evaluated using the Bio-Rad electrophoresis documentation system (Gel Doc 1000, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The total RNA was then converted into single-stranded cDNA with a cDNA synthesis kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Japan). The reaction conditions were as follows: 37°C for 15 min and 85°C for 5 sec. Amplification of the targeted genes was performed on a CFX96TM Real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) using SYBR Green PCR premix Ex Taq (Takara Bio, Inc.). The qPCR conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The relative expression values of the targeted genes were calculated using the comparative Cq (2−ΔΔCq) method (9). The primers used for the qPCR were synthesized by Sangon Corporation (Shanghai, China) and are shown in Table I.

Immunofluorescent staining

Following rinsing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the cells were fixed on coverslips with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, blocked with goat serum (Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China; cat. no. AR0009) and subsequently incubated with the indicated primary antibody (anti-E-cadherin or anti-vimentin; 1:100 dilution) overnight at 4°C. Following washing three times, the cells were incubated with DyLight 549-Conjugated Goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd.; cat. no. A23310; 1:100 dilution) or DyLight 549-Conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit Secondary Antibody (Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd.; cat. no. A23320; 1:100 dilution) at 37°C for 1 h. The nuclei of the cells were stained with 10 µg/ml DAPI at 37°C for 10 min. The fluorescent images were then observed and analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Images were typically selected from those of three repeated experiments.

Transwell assays

The cells were suspended at a density of 10×104/ml in medium without FBS and then placed in the upper part of the Transwell unit with polycarbonate filters (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA). Medium containing 10% FBS was added to the lower wells of the chambers. Following overnight culture at 37°C, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet at 37°C for 10 min. Three invasion chambers were used per treated group. The cells in the upper chamber were removed, washed with ddH2O and dried in air. The cell migration abilities were quantified by counting the number of cells that had passed through the membrane and fixed on the underside.

Dual-luciferase assay

The cells were seeded at ~70% confluence in 24-well culture plates, co-transfected with a luciferase reporter vector promoter construct (pGL3-basic, proE-cad-Luc or proE-cad-Luc-mEbox) and pRL-TK (an internal control) with either pcDNA4hismaxC-SIP1, shRNA or a control vector using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were then treated with TSA or DMSO. At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were collected and measured for luciferase activity on a GloMax microplate luminometer (Promega Corporation) using a dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega Corporation) according to the manufacturer's specifications. The firefly luciferase activity was normalized based on the Renilla luciferase activity. Assays were performed in triplicate and data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Treatment of the cells with TSA

The human hepatoma cell lines were plated at 30% confluence and cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2. TSA (500 µM) or DMSO (for control) were added and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. During continued incubation, fresh culture medium was provided every 24 h. Extracts were collected from the cells following DMSO or TSA treatment and analyzed by western blotting.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-iP) assay

The sonicated cell lysates were added to 0.7 ml of RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), incubated with anti-HBx or anti-SIP1 antibodies on a shaker at 4°C for 24 h, and incubated with protein A/G agarose (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for at 4°C 5 h. The immune-complexes were resolved by 10% SDS/PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare Life Science, Little Chalfont, UK) and probed with antibodies against HBx (1:500 dilution), SIP1 (1:1000 dilution) or HDAC1 (1000 dilution), as previously described in the western blotting protocol.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis

The treated cells (at ~90% confluence) were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde at 37°C for 15 min and treated with glycine buffer (1:10; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at 37°C for 5 min to quench the crosslinking reaction. Then, the samples were washed and resuspended in SDS lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) containing 1 mM PMSF. Following lysis on ice for 20 min, the samples were sonicated for 10 sec at 35 V with 30-sec spacing intervals for 10 min. Anti-SIP1 (1:200), anti-HBx (1:100) antibodies and immunoglobin G (negative control), and protein A+G Agarose/Salmon Sperm DNA (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) were added for immunoprecipitation. The precipitated DNA was purified (OD 260/280=1.8-2.0) and subjected to PCR amplification. In total, Two pairs of primers specific to the human E-cadherin promoter were used for PCR analysis (Table I). The synthesized products were separated on a 1% agarose gel and visualized with the Gel Doc 1000 electrophoresis documentation system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assays were used to determine cell viability in the cell proliferation assays. In brief, the cells were cultured at a density of 5×103 in a 96-well plate. After transfection, the cells were incubated for 12, 24, 36 and 48 h, and 10 µl CCK-8 solution (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Kumamoto, Japan) was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Absorbance at a wavelength of 490 nm was detected with a microplate reader. Each assay was performed three times in triplicate.

Cell apoptosis analysis

The cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 5×104 and transfected with the indicated plasmids for 48 h. The cells were then trypsinized, washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 95 µl of binding buffer and stained with 5 µl of Annexin V-FITC and 10 µl of propidium iodide (PI) working solution. Following incubating in the dark for 20 min, the cells were examined by flow cytometry.

Analysis of colony formation

For the clonogenicity analysis, at 24 h post-transfection, the transfected cells were seeded into 12-well plates at 500 cells (HepG2 cells) per well and maintained in complete medium for 2 weeks. The colonies were fixed with methanol and stained with crystal violet. The images were then observed using an optical microscope.

Tumorigenicity assays in nude mice

The animals were provided by the Laboratory Animal Centre of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China). The use of animals complied with the institutional guidelines and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital Affiliated to Chongqing Medical University. Nude mice were used to establish a mouse xenograft model.18 mice (male, 4-6 weeks old) were randomly divided into three groups, and housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle at 25°C and had free access to food and water. The HepG2 cell line and the HepG2-X cells infected with either shSIP1 or shCont were collected for subcutaneous injection (5×106 cells) into the mice (n=6 per group). The length and width of each tumor was monitored every week, and the tumor volume was calculated according to the following formula: Tumor volume (cm3)=length × (width × width)/2. At 6 weeks following subcutaneous injection, the nude mice bearing subcutaneous tumors were sacrificed and the subcutaneous tumor masses were isolated for further use within 4 h.

In vivo metastatic model

The tumor masses were cut into 1×1 mm pieces and steeped in RPMI-1640 that had been supplemented with 100 U/ml of penicillin and streptomycin. Another 15 six-week-old nude mice were randomly divided into three groups. Subsequently, a piece of tumor from one tumor-bearing mouse was carefully implanted into the liver of one of the new mice to establish a hepatoma orthotopic transplantation metastatic model. To determine the time to detect the tumor metastases in vivo, a preliminary experiment was performed. After 8 weeks, the mice were sacrificed, and the livers, diaphragm and lungs were removed and prepared for subsequent histological examination. All animal experiments followed a blind and randomized animal study protocol.

Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining

Liver and diaphragm tissues were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h at room temperature, and then dehydrated through ascending alcohol series. Paraffin-embedded blocks were cut into 5-µm-thick sections, dewaxed in xylene at room temperature, and rehydrated through decreasing ethanol series. Then, Sections were stained with HE at room temperature for histological analysis.

Statistical analysis

The study results are representative of at least three independent experiments. The data are shown as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis and graphical presentation were performed using the SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Inc.) and GraphPad Prism software (version 6; GraphPad Software, Inc.). Student's t-test was used for all statistical analyses between groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Influence of the ectopic expression of HBx on cell mobility and the expression of EMT-related proteins

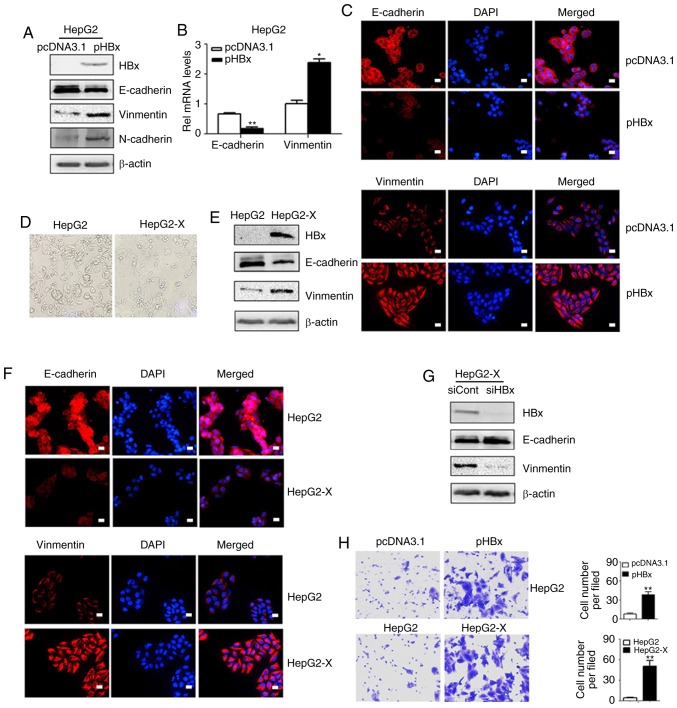

EMT is an important precursor to the invasion and metastasis of a hepatoma tumor. To examine whether HBx induced EMT directly, the HepG2 cells were transfected with the pHBx and the expression levels of the EMT-related proteins were examined by western blot analysis and immunofluorescent staining methods. As shown in Fig. 1A, the expression of HBx resulted in downregulation of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and a concomitant increase in the expression of the mesenchymal markers vimentin and N-cadherin. The RT-qPCR assay confirmed that the transcription levels of E-cadherin decreased and those of vimentin increased (Fig. 1B). Similar changes in E-cadherin and vimentin were observed by immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 1C). To further confirm these results, the HepG2-X cells were also examined. Once a monoclonal strain was established, the HepG2-X cells lost their overlapping growth characteristics and exhibited a fibroblast morphology while the parental HepG2 cells maintained highly organized cell-cell adhesion (Fig. 1D). Western blot analysis confirmed the decreased expression of E-cadherin and increased expression of vimentin in the HepG2-X cells (Fig. 1E). These results were further confirmed by immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 1F). By contrast, when the overexpression of HBx in HepG2-X cells was knocked down by siRNA, the repressed levels of E-cadherin were restored and the expression of vimentin was reduced (Fig. 1G).

Figure 1.

HBx protein promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition process and metastatic capacity of HepG2 cells. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 or pHBx. The expression levels of E-cadherin, Vimentin and N-cadherin were measured by western blot analysis. (B) mRNA levels of E-cadherin and Vimentin in HepG2 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 or pHBx were evaluated by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis. (C) Expression levels of E-cadherin and Vimentin were shown in immunofluorescent staining. Images are representative of three replicate experiments. (D) Morphological char-acterization of the HepG2 cell line and transduced HepG2-X cell line was evaluated by phase-contrast microscopy. (E) Western blot analysis of E-cadherin and Vimentin in the HepG2 and HepG2-X cell lines. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of E-cadherin and Vimentin in HepG2 and HepG2-X cell lines. DAPI was used to visualize nuclei. Scale bar, 10 µm. (G) Western blot analysis of E-cadherin and Vimentin in HepG2-X cells transfected with siHBx or siCont. (H) Transwell assay of HepG2 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 or pHBx, HepG2-X and parental HepG2 cell line. Magnification, ×200. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. HBx, hepatitis B virus X; pHBx, pcDNA3.1-HBx; siHbx, small interfering RNA targeting HBx; siCont, negative control small interfering RNA.

As increased cell migration is associated with EMT, Transwell assays were performed to detect cell mobility. The pHBx-transfected HepG2 cells demonstrated increased mobility in the Transwell assays compared with the pcDNA3.1 transfected cells. Similarly, increased cell mobility was observed in the HepG2-X cells compared with that in the parental cells (Fig. 1H).

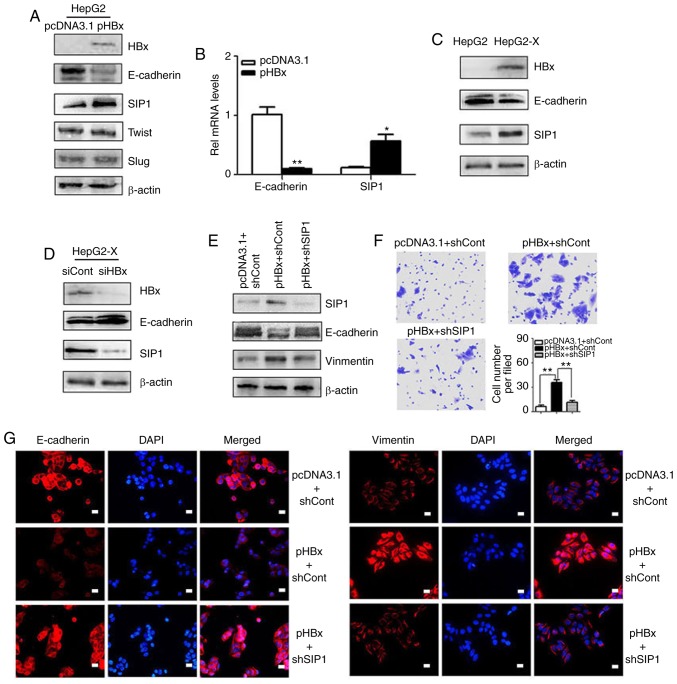

Epigenetic repression of E-cadherin by HBx is associated with SIP1

As an essential EMT protein marker, the repression of E-cadherin is normally required for cell migration and is associated with a poor cancer prognosis. The present study probed the molecular mechanisms through which HBx represses E-cadherin. In screening for the key regulators of the HBx-induced repression of E-cadherin in hepatoma cells, it was found that the transcription factor SIP1 was essential. Western blotting was used to investigate the expression of E-cadherin and several transcription factors implicated in EMT. Among these transcription factors, SIP1 exhibited increased expression in the pHBx-transfected HepG2 cells compared with that in the controls. SIP1 also exhibited a negative relationship with E-cadherin (Fig. 2A and B). A similar correlation was found between the expression levels of E-cadherin and SIP1 in HepG2-X cells that stably expressed HBx (Fig. 2C). By contrast, the knockdown of HBx by siRNA transfection in the HepG2-X cells resulted in the reduced expression of SIP1 and concomitant upregulation of E-cadherin (Fig. 2D), indicating close links between SIP1, E-cadherin and HBx.

Figure 2.

SIP1 is crucial in the HBx-induced epigenetic silencing of E-cadherin. (A) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related protein levels in HepG2 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 and pHBx were examined by western blotting. (B) mRNA levels of SIP1 in HBx-expressing HepG2 cells were verified by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). (C) Expression levels of SIP1 and E-cadherin in HepG2-X and HepG2 cells were examined by western blotting. (D) Western blot analysis of E-cadherin and SIP1 in HepG2-X cells transfected with siHBx or siCont. (E) Western blotting results. shRNA reduced the expression of SIP1 in HBx-expressing HepG2 cells, with nonspecific shRNA serving as a negative control. (F) Transwell assay of HepG2 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 or pHBx and treated with shSIP1 or scramble control. (G) Immunofluorescence analysis. The knockdown of SIP1 restored the epigenetic repression of E-cadherin induced by ectopic HBx. Vimentin concomitantly exhibited an inverse change in expression. DAPI was used to visualize nuclei. Scale bar, 10 µm. Magnification, ×200. SIP1, Smad-interacting protein 1; HBx, hepatitis B virus X; pHBx, pcDNA3.1-HBx; si, small interfering RNA; sh, short hairpin RNA.

To further examine whether SIP1 is a crucial factor in HBx-induced EMT, the present study examined whether the knockdown of SIP1 reverted the EMT phenotypes. Following the suppression of SIP1 by shRNAs in HBx-expressing HepG2 cells, the E-cadherin levels were restored (Fig. 2E). Subsequent immunofluorescent staining was performed to confirm the results. As shown in Fig. 2G, the loss of SIP1 in HBx-expressing HepG2 cells resulted in the increased expression of E-cadherin and decreased expression of vimentin. The Transwell migration analysis showed that the promoting effects of HBx on cell migration were abrogated by the down-regulation of SIP1 (Fig. 2F). Together, these data suggested that SIP1 may contribute to the epigenetic repression of E-cadherin mediated by HBx.

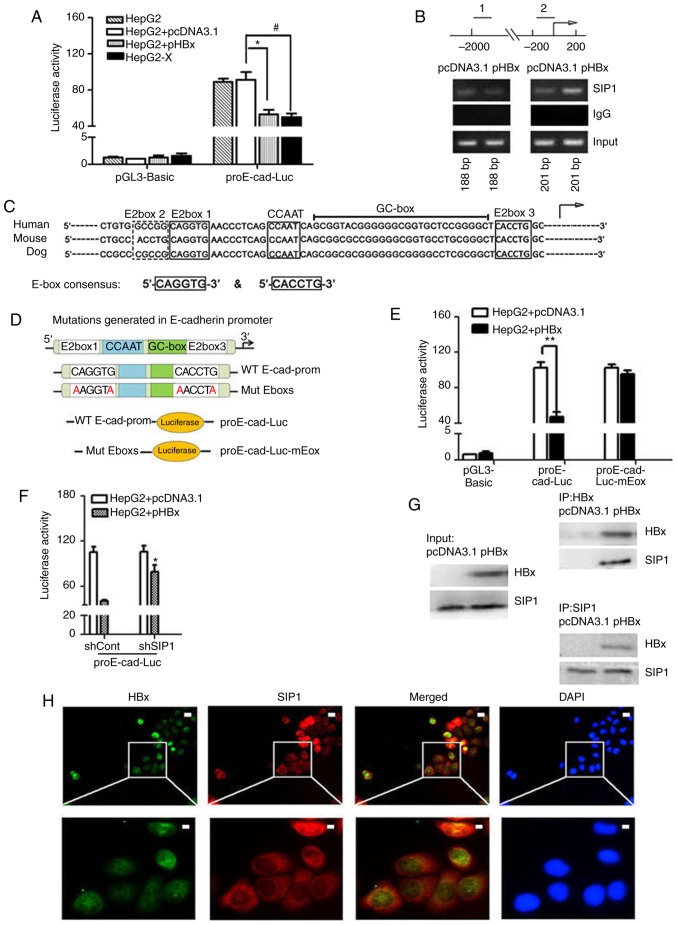

SIP1 migrates to the E-cadherin promoter region to repress its expression with the cooperation of HBx

As E-cadherin was downregulated at the transcriptional level following HBx introduction, it was hypothesized that HBx may directly regulate the promoter activity of E-cadherin. An E-cadherin promoter-luciferase reporter plasmid (proE-cad-Luc) was transfected into HepG2 cells to determine how HBx repressed the expression of E-cadherin. Consistent with the hypothesis, the overexpression of HBx significantly decreased the activity of the E-cadherin promoter in the HepG2 cells compared with that in the empty vector control or mock transfection cells (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

HBx recruits endogenous SIP1 to the E-cadherin promoter. (A) Dual-luciferase assay of human E-cadherin promoters in Mock treated, pcDNA3.1 or pHBX transfected HepG2 cells and HepG2-X cells. Data were normalized to the luciferase activity of cells treated with pcDNA3.1 and pGL3-Basic. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. *P<0.05 HepG2 + pcDNA3.1 vs. HepG2 + pHBx; #P<0.05 HepG2 + pcDNA3.1 vs. HepG2-X. (B) ChIP primers were designed on E-cadherin gene regulatory regions. Distal primers correspond to downstream regulatory regions (1) of -1895 to -1707 nt of the E-cadherin gene. The ChIP primers (2) were designed adjacent to the TSS locations across the E-box region of the human E-cadherin promoter. pHBx-transfected HepG2 cell lysates were subjected to ChIP using an anti-SIP1 antibody. PCR was conducted using the indicated primer pairs. An empty vector and IgG served as external and internal negative controls. (C) Sequence homology of the consensus E-box in the E-cadherin promoter of mammalian. E-boxes 1, 3 and 4, CCAAT box and GC box are conserved regulatory elements, as shown in the diagram. The arrow indicates the putative TSS. (D) Mutations generated in the E-boxes carried the E-box 1 mutation CAGGTG → AAGGTA and E-box 3 mutation CACCTG → AACCTA. The wild-type E-cadherin promoter and promoter comprising two mutated E-boxes were cloned into a luciferase vector to construct the proE-cad-Luc and proE-cad-Luc-mEbox plasmids. (E) Dual-luciferase assay of E-cadherin promoter constructs with proE-cad-Luc or proE-cad-Luc-mEbox in pHBx- or pcDNA3.1-transfected HepG2 cells. **P<0.01. (F) Relative E-cadherin promoter activities inshSIP1/shCont and pcDNA3.1/pHBX treated HepG2 cells. *P<0.05; (shSIP1 + WT, vs. shCont + WT). (G) Co-immunoprecipitation in protein extracts of pcDNA3.1-transfected HepG2 cells and HBx-expressing HepG2 cells with anti-SIP1 or anti-HBx antibodies and western blot detection of HBx and SIP1, respectively. (H) Immunofluorescent staining of HepG2-X cells with anti-HBx and anti-SIP1 to show the subcel-lular co-localization of HBx and SIP. DAPI was used to visualize nuclei. Scale bar=10 µm. SIP1, Smad interacting protein 1; HBx, hepatitis B virus X; pHBx, pcDNA3.1-HBx; sh, short hairpin RNA. TSS, transcription start site; WT, proE-cad-Luc; Mut, proE-cad-Luc-mEbox; ChIp, chromatin immunoprecipitation.

As suggested in previous research, E-boxes within the human E-cadherin promoter are conserved among mammalian sequences (Fig. 3C). The two E-boxes (E-box 1 and 3) that cover the proximal transcription start site have been shown to serve a crucial role in regulating E-cadherin by providing binding sites for SIP1 (10-12). To examine whether HBx regulates the expression of E-cadherin by enhancing SIP1 binding to E-cadherin promoter, ChIP assays were performed. The results revealed that HBx strengthened the binding of SIP1 to E-cadherin promoter fragments that spanned the E-boxes (Fig. 3B). To further elucidate the effect of this binding complex on the E-cadherin promoter, a luciferase reporter plasmid constructed with an E-cadherin promoter that had mutated E-boxes (mutated in both E-box1 and E-box3) was introduced (Fig. 3D). The results showed that the mutation of key nucleotides eliminated the HBx-induced inhibition of the reporter gene activity (Fig. 3E). By contrast, the knockdown of SIP1 in the pHBx-transfected HepG2 cells increased the wild-type E-cadherin promoter-driven luciferase activity (Fig. 3F). These data indicated that HBx may suppress the activity of the E-cadherin promoter by enhancing SIP1 binding to spaced E-boxes.

To elucidate whether there was a physical interaction between HBx and Sip1, Co-IP analysis of HBx-expressing HepG2 cells was performed. The results showed that SIP1 effectively bound to HBx in the HBx-expressing HepG2 cells (Fig. 3G). Subsequently, the subcellular distribution of HBx and SIP1 in HepG2-X cells were examined via immunofluorescent staining. As shown in Fig. 3H, SIP1 primarily localized in the perinuclear region of the cytoplasm; a lower level had translocated into the nucleus, with overlapping subcellular distribution of HBx in the HepG2-X cells, particularly in the nucleus. The present results suggested that HBx may cooperate with SIP1 to repress the expression of E-cadherin inside the cell nucleus at the E-box sites of the E-cadherin promoter.

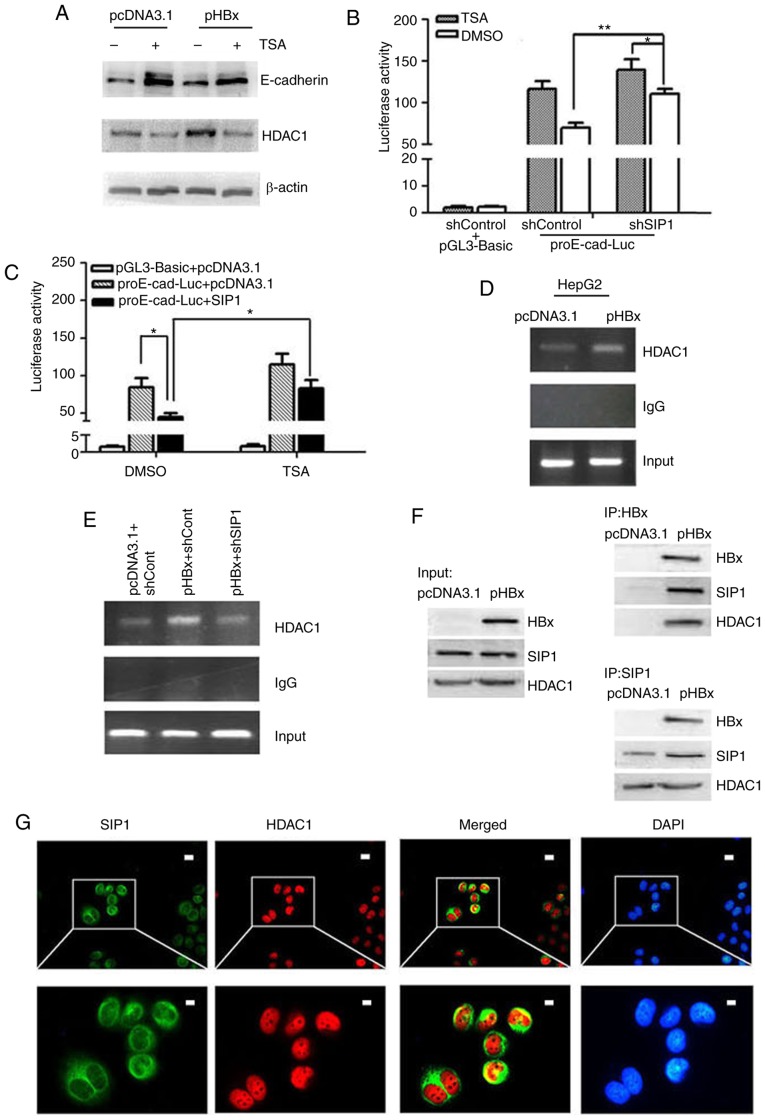

HBx recruits SIP1 and HDAC1 to repress the E-cadherin promoter

HDAC1 has been reported to epigenetically modify the expression of various genes, therefore, the present study examined whether HDAC1 is involved in the HBx-mediated repression of E-cadherin. When the HepG2 cells were treated with TSA, an HDAC inhibitor, the expression levels of E-cadherin increased significantly and the HBx-mediated repression of E-cadherin was reversed to a certain level (Fig. 4A). In addition, compared with the pcDNA3.1 transfection control, HBx transfection increased the expression of HDAC1 significantly. These results indicated that histone deacetylation may be one of the mechanisms that HBx utilizes to regulate the expression of E-cadherin.

Figure 4.

HBx recruits SIP1 and HDAC1 to the E-cadherin promoter to repress its expression. (A) Western blot analysis of E-cadherin and HDAC1 in pcDNA3.1 or pHBX transfected HepG2 cells +/- TSA. E-cadherin promoter activities in TSA-treated cells following transfection with (B) shSIP1 or (C) SIP1 expression plasmids. Results are reported as the relative luciferase activity, vs. activity of pGL3-Basic. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (mean ± SD). (D) ChIP of lysates from HepG2 cells transfected with pHBx using anti-HDAC1 antibody. An empty vector pcDNA3.1 and protein G beads served as external and internal controls, respectively. (E) ChIP performed using HDAC1 antibody on the lysates of HepG2 cells treated with shSIP1/shCont and pcDNA3.1/pHBX. (F) Co-immunoprecipitation of HBx-expressing HepG2 cell-protein extracts with anti-SIP1 or anti-HBx antibodies and western blot detection of HDAC1, HBx and SIP1, respectively. (G) Immunofluorescent staining of HepG2-X cells with anti-HDAC1, anti-SIP1 and DAPI. The merged image showed HDAC1 and SIP1 co-localization in the nucleus. Scale bar=10 µm. SIP1, Smad-interacting protein 1; HBx, hepatitis B virus X; pHBx, pcDNA3.1-HBx; sh, short hairpin RNA; Cont, control; HDAC1, histone deacetylase 1; ChIp, chromatin immunoprecipitation; TSA, trichostatin A.

The synergistic effect of SIP1 and HDAC1 on the activity of the E-cadherin promoter was subsequently analyzed. In the HepG2-X cells, TSA and shSIP1 enhanced E-cadherin promoter activity. Additionally, the combined treatment with shSIP1 and TSA increased E-cadherin promoter activity more than any single treatment in the HepG2-X cells (Fig. 4B). By contrast, the overexpression of SIP1 resulted in marked repression of E-cadherin promoter activity, and a small decrease was observed in the E-cadherin promoter activity levels when TSA was administered together with the SIP1 plasmid (Fig. 4C). Therefore, HBx likely repressed E-cadherin promoter activity through SIP1 and HDAC1.

To further understand the role of HDAC1, ChIP analysis was performed with HDAC1 immunoprecipitates. The results revealed that HDAC1 bound to the E-cadherin promoter and HBx enhanced this binding activity (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, HDAC1 binding to the E-cadherin promoter was inhibited following transfection with shSIP1 (Fig. 4E). To confirm the direct binding affinity of HBx, SIP1 and HDAC1, a triple Co-IP analysis was performed. As shown in Fig. 4F, anti-HBx antibody precipitated SIP1 and HDAC1 at the same time, showing an interacting effect of HBx to SIP1 and HDAC1. When the cell lysates were precipitated by anti-SIP1, HBx and HDAC1 proteins were detected in the HBx-transfected cells. The subcellular localization of SIP1 and HDAC1 in immunofluorescence assays also suggested that SIP1 and HDAC1 localized in the same region in the HepG2-X cells (Fig. 4G).

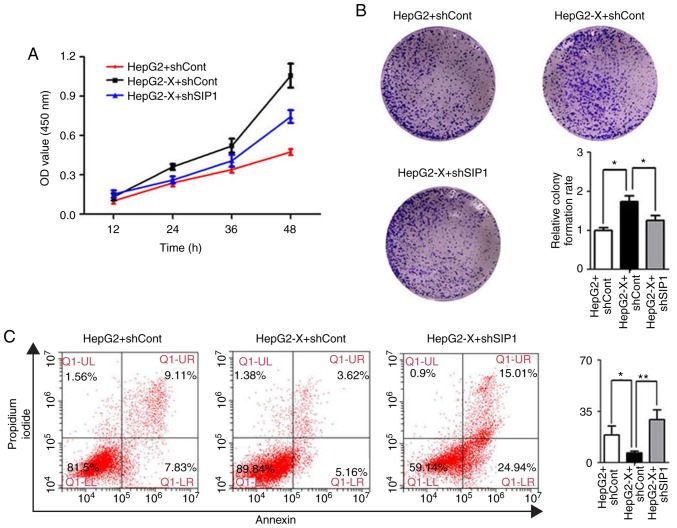

Knockdown of SIP1 suppresses the oncogenic activity of HBx in HepG2 cells

HBx is known to modulate cell growth, cell-cycle progression and migration. The present study subsequently examined whether SIP1 is involved in these processes. The CCK-8 assay indicated that the introduction of HBx significantly increased the cell growth rate compared with that in the control cells. When SIP1 was knocked down by shRNA, the increased proliferation rate of the HBx-expressing HepG2 cells almost returned to the original levels (Fig. 5A). These results suggested that SIP1 serves a vital role in HBx-regulated cell growth.

Figure 5.

SIP1 mediates cell proliferation and apoptosis affected by ectopic expression of HBx in HepG2 cells. (A) HepG2 and HepG2-X cells were trans-fected with shSIP1 or shCont. Cell counting kit-8 assays were performed to determine cell proliferation ability. (B) Colony formation assay in HepG2 and HepG2-X cells transfected with shSIP1 or shCont. The colonies were stained with crystal violet and counted. Images are representative of three replicate experiments. (C) Apoptosis of HepG2 and HepG2-X cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. SIP1, Smad-interacting protein 1; HBx, hepatitis B virus X; sh, short hairpin RNA; Cont, control.

Dual staining (Annexin V and PI) of the liver cancer cells was performed, followed by flow cytometric analysis to determine the effect of SIP1 and HBx on cell apoptosis. The Annexin V/PI assays indicated that there was a marked decrease in the apoptotic rate of the HBx-expressing HepG2 cells compared with that of the controls (Fig. 5C). However, the knockdown of SIP1 antagonized the effect of HBx and reverted the apoptotic rate.

Subsequently, colony formation assays were performed to further elucidate the effect of HBx and SIP1 on cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 5B, HBx significantly enhanced HepG2 cell proliferation, whereas the knockdown of SIP1 by shRNA in HepG2-X cells resulted in a reduced proliferation rate. Taken together, these results showed that HBx is widely engaged in modulating the oncogenic activity of liver cancer cells in vitro and that SIP1 exerts an important influence in the process.

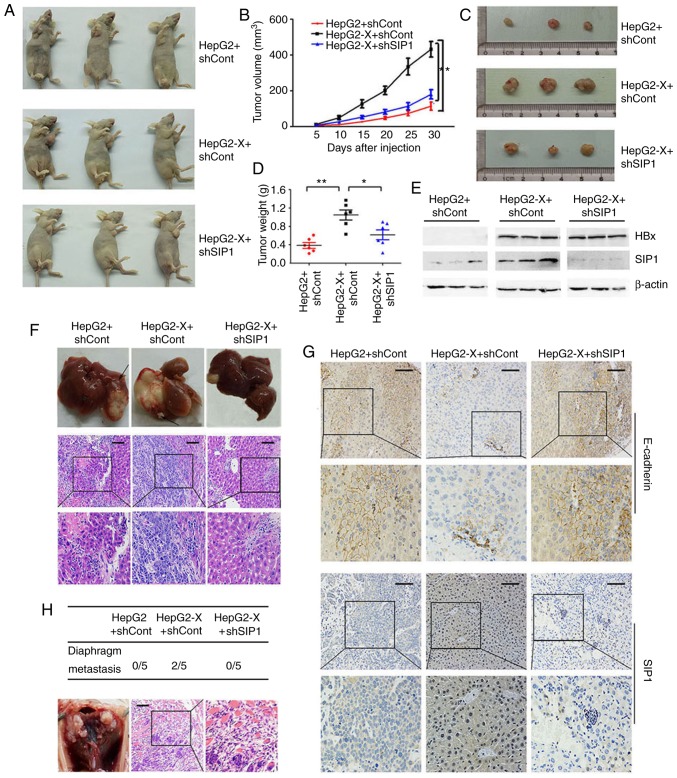

SIP1 is involved in HBx-induced tumorigenesis and liver cancer metastasis in vivo

To examine the role of SIP1 in HBx-induced tumorigenesis and liver cancer aggressiveness, the tumor formation of liver cancer cells expressing HBx was evaluated in tumorigenicity assays on athymic nude mice. The nude mice that were subcutaneously injected with the HepG2-X cells had a larger tumor volume and increased tumor weight compared with those received the parental HepG2 control cells (n=6 per group). When the expression of SIP1 was knocked down by shRNA interference in the HepG2-X cells, the tumor volume ratio and the tumor weight were reduced significantly (Fig. 6A-D). The effect of the knockdown of SIP1 was verified by western blotting (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

HBx accelerates tumor growth through SIP1 in vivo. (A) Representative images of nude mice implanted with HepG2 and HepG2-X cells treated with shSIP1 or shCont. (B) Growth curves of tumors from nude mice implanted with the indicated cells (xenograft mice). (C) Images of tumors from xenograft mice. (D) Average tumor weights from xenograft mice. (E) Expression of SIP1 and E-cadherin in tumor tissues of mice was detected using western blotting. (F) Representative images of liver tissues and H&E staining of intrahepatic metastasis tumors from each group of orthotopic transplantation mice were shown. The arrows indicate visible intrahepatic metastatic tumors. (G) Immunohistochemical analysis of the transplanted tumors from each group of orthotopic transplantation mice. (H) H&E staining of the diaphragm metastases was detected only in the shCont-treated HepG2-X cells group of mice. Scale bar, 150 µm. SIP1, Smad-interacting protein 1; HBx, hepatitis B virus X; si, small interfering RNA; sh, short hairpin RNA; Cont, control; H&E hematoxylin and eosin.

To further determine the influence of SIP1 on the metastatic capacity of liver cancer cells caused by HBx in vivo, a hepatic orthotopic transplantation metastatic animal model was developed. The mice that were transplanted with the tumor masses from the HepG2-X cells carrying shCont developed more expansive liver tumors compared with those transplanted with tumors derived from the mock-transfected HepG2 cells (Fig. 6F). Visible intrahepatic metastatic tumors and the HE staining of liver tissue, with the exception of the orthotopically transplanted portion, indicated wider intrahepatic metastasis. The knockdown of SIP1 in HBx-expressing cells led to a significant decrease in liver tumor size and the scope of intra-hepatic migration (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, tumor metastasis from the transplanted hepatic tumor to the diaphragm tissue was only detected in the HepG2-X tumor-transplanted mice. H&E staining of the diaphragm tissues verified that the metastatic tumor had the same morphology as the original hepatic tumors (Fig. 6H). Immunohistochemical analysis of the transplanted tumor confirmed the repressed levels of E-cadherin and increased levels of SIP1 following HBx introduction (Fig. 6G). Consistent with the in vitro results, the silencing of SIP1 efficiently restored the expression of E-cadherin in the tumors.

Discussion

Accumulated evidence supports HBV as an important cause of liver cancer by modulating different signal transduction pathways involved in EMT (13-17). Various transcriptional regulators have been identified as important EMT mediators, including ZEB1, SIP1, Slug and Twist (18-20). As one of only two members of the vertebrate ZFH1 family, SIP1, also known as ZEB2, was initially found to bind to the MH2 domain of SMAD1. SIP1 was later revealed to interact with SMAD2, SMAD3 and SMAD5 (21,22) and to regulate Smad-dependent TGF-β signal transduction pathways. SIP1 was also reported to be implicated in embryonic development and cancer progression (23,24). However, whether SIP1 serves a role in HBV-induced liver cancer has not been discussed previously.

In the present study, it was found that ectopic HBx resulted in the increased expression of SIP1 and decreased expression of E-cadherin, leading to EMT change of the HepG2 cells. In addition, changes in the EMT protein markers induced by HBx were reversed by modulation of the expression of SIP1. As a member of the δEF1 family, SIP1 is characterized by a homeodomain with two clusters of highly conserved zinc fingers: An N-terminal cluster consisting of four zinc fingers (NFZ) and a C-terminal cluster containing three zinc fingers (CFZ) (23). SIP1 occupies promoter elements by NZF binding to one-spaced CACCT DNA sequences, including E-boxes (CACCTG), and CZF binding to the other. The binding of SIP1 to the two conserved E-boxes represses the activity of the E-cadherin promoter (25). The data obtained in the present study indicated that HBx suppressed the activity of the E-cadherin promoter by increasing the expression of SIP1 and enhancing its ability to efficiently bind to the E-cadherin promoter in HepG2 cells.

Previous studies have reported that HDAC1 is involved in the epigenetic modifications of tumor genes and tumor-suppressing genes in various types of cancer. The expression of HDAC1 in liver cancer is high (26). HDAC1 was selected as a candidate molecule for investigation in the present study. An increase of HDAC1 in HBx-expressing cells was observed, consistent with the former reports (27,28). Additionally, HDAC1 was found to form a triple complex with HBx and SIP1, which combined with the promoter of E-cadherin and repressed its transcriptional activity. ZEB1 has been reported to form a multi-protein complex with HDAC1 and HDAC2 to regulate the transcription of target genes (29,30). In the present study, SIP1 was also observed to partially co-localize with HBx and HDAC1 in subcellular sites. It appears that HBx recruits SIP1 and facilitates its binding to DNA, together with HDAC1. The present study focused only on HDAC1. However, other HDACs may be also involved in the regulation of ZEB2 (SIP1) and the investigation of other HDAC members is anticipated in the future.

The reduced expression of E-cadherin interrupts inter-cellular adhesion and conjunction, which facilitates the aggressiveness of tumors. HBx has been reported to promote liver cancer through influencing E-cadherin by several mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, Wnt, Snail and mSin3A (31-34). In the present study, SIP1 was identified as an important regulator in the HBx-induced modification of E-cadherin. The knockdown of SIP1 abrogated the promoting effect of HBx on cell proliferation, growth and migration. In subcutaneous transplantation mice and hepatoma orthotopic implantation mice, HBx promoted tumor growth, development and metastasis, whereas the sustainable knockdown of SIP1 efficiently attenuated the HBx-induced promotion of tumorigenicity and aggressiveness. These data indicate a key role of SIP1 in the process of HBx-induced tumorigenicity and metastasis.

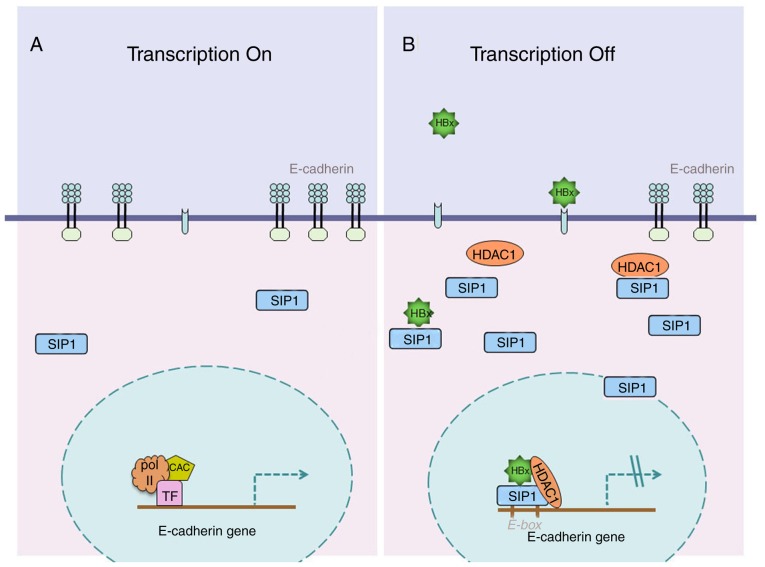

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that SIP1 serves a pivotal role in HBx-induced liver cancer growth and metastasis. The study presents a novel mechanism for HBV-related liver cancer (Fig. 7) and may help to examine novel potential therapeutic approaches.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram showing how HBx regulates E-cadherin via SIP1 and histone deacetylation. (A) Abundant enrichment of CAC and TFs are recruited to E-cadherin promoter region in the absence of HBx protein, leading to the transcription of E-cadherin. (B) HBx protein increases the levels of SIP1 and HDAC1. The three factors form a repressive triple complex locates at the E-cadherin promoter, and then induces the epigenetic silencing of E-cadherin. SIP1, Smad-interacting protein 1; HBx, hepatitis B virus X; TF, transcription factor; Pol II, RNA polymerase II.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Janet E. Mertz (McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health) for providing the pcDNA4hismaxC-SIP1 plasmids.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81672080 and 81873971) and a grant from Chongqing Health and Family Planning commission (grant no. 20141005).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

WXC initiated the project. DDL, PL, LD and BW designed and monitored the experiments. JJM, QH, JY, QFY and HC performed the experiments. YYY contributed to writing the manuscript. JC and WXC read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animals were provided by the Laboratory Animal Centre of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China). The use of the animals complied with the institutional guidelines and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital Affiliated to Chongqing Medical University.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Zhang XD, Wang Y, Ye LH. Hepatitis B virus X protein accelerates the development of hepatoma. Cancer Biol Med. 2014;11:182–190. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buendia MA, Neuveut C. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5:a021444. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park NH, Song IH, Chung YH. Molecular pathogenesis of Hepatitis-B-virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut Liver. 2007;1:101–117. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2007.1.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeger C, Mason WS. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:51–68. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.1.51-68.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minor MM, Slagle BL. Hepatitis B virus HBx protein interactions with the ubiquitin proteasome system. Viruses. 2014;6:4683–4702. doi: 10.3390/v6114683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang H, Oishi N, Kaneko S, Murakami S. Molecular functions and biological roles of hepatitis B virus x protein. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:977–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali A, Abdel-Hafiz H, Suhail M, Al-Mars A, Zakaria MK, Fatima K, Ahmad S, Azhar E, Chaudhary A, Qadri I. Hepatitis B virus, HBx mutants and their role in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10238–10248. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Q, Li W, Ren J, Huang Y, Huang Y, Hu Q, Chen J, Chen W. ZEB2 inhibits HBV transcription and replication by targeting its core promoter. Oncotarget. 2016;7:16003–16011. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comijn J, Berx G, Vermassen P, Verschueren K, van Grunsven L, Bruyneel E, Mareel M, Huylebroeck D, van Roy F. The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00260-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behrens J, Löwrick O, Klein-Hitpass L, Birchmeier W. The E-cadherin promoter: Functional analysis of a G.C-rich region and an epithelial cell-specific palindromic regulatory element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11495–11499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giroldi LA, Bringuier PP, de Weijert M, Jansen C, van Bokhoven A, Schalken JA. Role of E boxes in the repression of E-cadherin expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:453–458. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin-Lluesma S, Schaeffer C, Robert EI, van Breugel PC, Leupin O, Hantz O, Strubin M. Hepatitis B virus X protein affects S phase progression leading to chromosome segregation defects by binding to damaged DNA binding protein 1. Hepatology. 2008;48:1467–1476. doi: 10.1002/hep.22542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arbuthnot P, Capovilla A, Kew M. Putative role of hepatitis B virus X protein in hepatocarcinogenesis: Effects on apoptosis, DNA repair, mitogen-activated protein kinase and JAK/STAT pathways. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:357–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kew MC. Hepatitis B virus x protein in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):S144–S152. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin Kim S, Yeom S, Kwak J, Ahn HJ, Lib Jang K. Hepatitis B virus X protein induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition by repressing E-cadherin expression via upregulation of E12/E47. J Gen Virol. 2016;97:134–143. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Bode AM, Dong Z, Cao Y. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is regulated by oncoviruses in cancer. FASEB J. 2016;30:3001–3010. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600388R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cobaleda C, Pérez-Caro M, Vicente-Dueñas C, Sánchez-García I. Function of the zinc-finger transcription factor SNAI2 in cancer and development. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:41–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Grunsven LA, Michiels C, Van de Putte T, Nelles L, Wuytens G, Verschueren K, Huylebroeck D. Interaction between Smad-interacting protein-1 and the corepressor C-terminal binding protein is dispensable for transcriptional repression of E-cadherin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26135–26145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verschueren K, Remacle JE, Collart C, Kraft H, Baker BS, Tylzanowski P, Nelles L, Wuytens G, Su MT, Bodmer R, et al. SIP1, a novel zinc finger/homeodomain repressor, interacts with Smad proteins and binds to 5′-CACCT sequences in candidate target genes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20489–20498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Remacle JE, Kraft H, Lerchner W, Wuytens G, Collart C, Verschueren K, Smith JC, Huylebroeck D. New mode of DNA binding of multi-zinc finger transcription factors: deltaEF1 family members bind with two hands to two target sites. EMBO J. 1999;18:5073–5084. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.5073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerchner W, Latinkic BV, Remacle JE, Huylebroeck D, Smith JC. Region-specific activation of the Xenopus brachyury promoter involves active repression in ectoderm and endoderm: A study using transgenic frog embryos. Development. 2000;127:2729–2739. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Grunsven LA, Schellens A, Huylebroeck D, Verschueren K. SIP1 (Smad interacting protein 1) and deltaEF1 (delta-crystallin enhancer binding factor) are structurally similar transcriptional repressors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(Suppl 1):S40–S47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ropero S, Esteller M. The role of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in human cancer. Mol Oncol. 2007;1:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoo YG, Na TY, Seo HW, Seong JK, Park CK, Shin YK, Lee MO. Hepatitis B virus X protein induces the expression of MTA1 and HDAC1, which enhances hypoxia signaling in hepa-tocellular carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:3405–3413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shon JK, Shon BH, Park IY, Lee SU, Fa L, Chang KY, Shin JH, Lee YI. Hepatitis B virus-X protein recruits histone deacety-lase 1 to repress insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 transcription. Virus Res. 2009;139:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aghdassi A, Sendler M, Guenther A, Mayerle J, Behn CO, Heidecke CD, Friess H, Büchler M, Evert M, Lerch MM, Weiss FU. Recruitment of histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2 by the transcriptional repressor ZEB1 downregulates E-cadherin expression in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2012;61:439–448. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider G, Krämer OH, Saur D. A ZEB1-HDAC pathway enters the epithelial to mesenchymal transition world in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2012;61:329–330. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srisuttee R, Koh SS, Kim SJ, Malilas W, Boonying W, Cho IR, Jhun BH, Ito M, Horio Y, Seto E, et al. Hepatitis B virus X (HBX) protein upregulates β-catenin in a human hepatic cell line by sequestering SIRT1 deacetylase. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:276–282. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen L, Zhang X, Hu D, Feng T, Li H, Lu Y, Huang J. Hepatitis B virus X (HBx) play an anti-apoptosis role in hepatic progenitor cells by activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;383:213–222. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie Q, Chen L, Shan X, Shan X, Tang J, Zhou F, Chen Q, Quan H, Nie D, Zhang W, et al. Epigenetic silencing of SFRP1 and SFRP5 by hepatitis B virus X protein enhances hepatoma cell tumorigenicity through Wnt signaling pathway. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:635–646. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arzumanyan A, Friedman T, Kotei E, Ng IO, Lian Z, Feitelson MA. Epigenetic repression of E-cadherin expression by hepatitis B virus x antigen in liver cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:563–572. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.