This longitudinal cohort study investigates whether prior convictions for driving under the influence are associated with the risk of subsequent arrests for a violent crime among handgun purchasers in California aged 21 to 49 years at the time of purchase in 2001.

Key Points

Question

Are prior convictions for driving under the influence associated with the risk of subsequent arrest for a violent crime among legal purchasers of handguns?

Findings

In this longitudinal cohort study of 79 678 handgun purchasers in California, 9% of the purchasers with prior convictions for driving under the influence and 2% of the purchasers with no prior criminal history were subsequently arrested for murder, rape, robbery, or aggravated assault during the 13 years of follow-up.

Meaning

This study’s findings suggest that prior convictions for driving under the influence may be associated with the risk of subsequent arrest for a violent crime among legal purchasers of handguns.

Abstract

Importance

Alcohol use is a risk factor for firearm-related violence, and firearm owners are more likely than others to report risky drinking behaviors.

Objective

To study the association between prior convictions for driving under the influence (DUI) and risk of subsequent arrest for violent crimes among handgun purchasers.

Design

In this retrospective, longitudinal cohort study, 79 678 individuals were followed up from their first handgun purchase in 2001 through 2013. The study cohort included all legally authorized handgun purchasers in California aged 21 to 49 years at the time of purchase in 2001. Individuals were identified using the California Department of Justice (CA DOJ) Dealer’s Record of Sale (DROS) database, which retains information on all legal handgun transfers in the state.

Exposures

The primary exposure was DUI conviction prior to the first handgun purchase in 2001, as recorded in the CA DOJ Criminal History Information System.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prespecified outcomes included arrests for violent crimes listed in the Crime Index published by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault), firearm-related violent crimes, and any violent crimes.

Results

Of the study population (N=79 678), 91.0% were males and 68.9% were white individuals; the median age was 34 (range, 21-49) years. The analytic sample for multivariable models included 78 878 purchasers after exclusions. Compared with purchasers who had no prior criminal history, those with prior DUI convictions and no other criminal history were at increased risk of arrest for a Crime Index–listed violent crime (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR], 2.6; 95% CI, 1.7-4.1), a firearm-related violent crime (AHR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.3-6.4), and any violent crime (AHR, 3.3; 95% CI, 2.4-4.5). Among purchasers with a history of arrests or convictions for crimes other than DUI, associations specifically with DUI conviction remained.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s findings suggest that prior DUI convictions may be associated with the risk of subsequent violence, including firearm-related violence, among legal purchasers of handguns. Although the magnitude was diminished, the risk associated with DUI conviction remained elevated even among those with a history of arrests or convictions for crimes of other types.

Introduction

Firearm violence is a public health and safety problem in the United States, with 14 542 homicides and more than 400 000 violent victimizations involving a firearm in 2017.1,2 Alcohol consumption is a known risk factor for violence perpetration, including violence that involves firearms, and firearm owners are more likely than others to report risky drinking behaviors.3,4,5,6 In a meta-analysis of studies involving homicide offenders, an estimated 34% of people who committed homicide with a firearm were under the influence of alcohol at the time of the crime.7 Hypothesized mechanisms of action include the direct neurocognitive effects related to alcohol use, which facilitate aggression; an underlying propensity to engage in harmful activities, including both risky alcohol use and violent behavior; and interactions between these factors.5,8

Given the association between alcohol use and violence, including firearm violence, many states have adopted statutes limiting firearm purchase or possession by persons with a history of risky alcohol use.9 However, the standards are often vaguely defined and difficult to implement. For example, Ohio prohibits firearm possession by anyone who is a “habitual drunkard,”10 and Tennessee prohibits the sale of firearms to those “who are addicted to alcohol.”11 Only Indiana, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Washington, DC, have well-defined standards for prohibiting firearm possession among those with a history of risky alcohol use, such as accruing 3 or more convictions for driving under the influence (DUI) during a specified period.4

California has enacted restrictions for firearm access beyond those in federal laws. For example, in 1990, a state law prohibited firearm purchase or possession for a period of 5 years among those admitted to an inpatient psychiatric facility for an evaluation of dangerousness to self or others.12 In 1991, the restrictions in California were expanded to prohibit firearm purchase and possession for 10 years among people with convictions for specific misdemeanor violent crimes.13 In 2013, the California Legislature enacted a 10-year prohibition on firearm purchase and possession by people who accrued 2 or more convictions for DUI or certain other alcohol-related misdemeanor crimes within a 3-year period.14 Jerry Brown, California’s then-governor, vetoed the bill, citing a lack of evidence linking “crimes that are non-felonies, non-violent, and do not involve misuse of firearms”15 to violent behavior or improper firearm use.

A prior study from our research group assessed the association between risky alcohol use and the risk of future violence among firearm owners.16 The study, published in 2018, found that handgun purchasers in California with histories of alcohol-related crimes (particularly DUI crimes) were at increased risk of subsequent arrest for violent or firearm-related crimes. The prior study was limited; for example, it relied on old data (handgun purchases were made in 1977 and follow-up was through 1991), and the sample size was small, including 4066 purchasers, of whom 1272 had prior convictions for alcohol-related crimes. Of those with prior alcohol-related convictions, 32.8% were subsequently arrested for a violent or firearm-related crime compared with 5.7% of those with no prior criminal history.

In this retrospective longitudinal study, we estimated the association between prior convictions for DUI and the risk of subsequent arrest for violent crimes listed in the Crime Index published by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault)17 among legally authorized purchasers of handguns in California, using a larger study population and more recent data. We also estimated associations using a broader category of alcohol-related crimes and for the following 2 secondary outcomes: arrest for firearm-related violent crimes and for any violent crimes.

Methods

The University of California, Davis Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol18 and waived the need for obtaining informed consent.

Study Population

The study population included all legal purchasers of handguns in California in 2001 who were aged 21 to 49 years as of the 10th postpurchase day, the first day on which firearms could be acquired (California requires a 10-day waiting period). For the individuals who made multiple purchases in 2001, follow-up began after the first purchase. The selected age range reflects the facts that handgun purchasers in California must be aged at least 21 years, and violent crime rates among persons 50 years or older are relatively low.19 The study cohort was identified using the California Department of Justice (CA DOJ) Dealer’s Record of Sale (DROS) database, which retains information on all legal handgun transfers in the state.

The study participants were followed up from their 10th postpurchase day in 2001 until December 31, 2013, or a prior date when they could no longer be affirmatively identified as living California residents using public records. These records initially included the California Death Statistical Master File, California voter registration records, and DROS records. If a period of 3 years or more for an individual remained unaccounted for (53.0% of the study sample), we queried LexisNexis Public Records (see eAppendix 1 in the Supplement).

Exposures and Outcomes

Our main exposure was DUI conviction prior to the index purchase. We tested associations for any prior DUI conviction and for the number of DUI convictions (1, ≥2). Conviction for other alcohol-related crimes (eg, public drunkenness) served as a secondary exposure. Crimes not involving alcohol consumption, such as having an open container in the vehicle, were excluded from this category. We linked the participants to the Criminal History Information System records by using deterministic and probabilistic matching to identify the exposure status.20

Our primary outcome was an arrest charge for a Crime Index–listed violent crime, which includes murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.17 We used arrest charges because they are recorded more rapidly and completely than are convictions.21 Although not all criminal charges corresponded to an arrest event, we have referred to these as arrests throughout for simplicity. Secondary outcomes were arrests for firearm-related violent crimes and an umbrella category of all violent crimes, defined following the Federal Bureau of Investigation and World Health Organization recommendations.17,22,23 Secondary outcomes also included convictions for each outcome.

Covariates

Individual-level control variables included sex, age, and self-reported race/ethnicity (DROS categories were collapsed to include American Indian, Asian, black, Latino, white, and other individuals) recorded in DROS; the number of handguns purchased from 1985 (the earliest year for which records were available) until the index purchase (0, 1-3, or ≥4); and time elapsed between the most recent DUI and non–DUI-related arrests and the index purchase for individuals with prior criminal histories (0-2, >2 years). Community characteristics included census tract demographics (population size and density, proportion of persons aged 20 to 44 years who were aged 20 to 24 years, and percentages of males, Latino individuals, and black individuals) from the American Community Survey with annual interpolations by Geolytics24,25; census tract alcohol outlet densities using 4 separate license types (bar/pub/tavern, restaurant [beer, wine], restaurant [spirits], and off premises)26; county population and violent and property crime rates27; and county firearm suicides as a proportion of total suicides (2001-2013), a proxy for firearm ownership prevalence.28,29 We adjusted for socioeconomic status using a census tract–level index that combined standard indicators (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

The data analysis was conducted from December 2017 to August 2019. We used Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) with 95% CIs. We included DUI history as a 3-level variable to categorize purchasers as having convictions at the time of purchase, arrests but no convictions, or neither (the referent group). We hypothesized that having a history of arrests or convictions for crimes other than DUI may affect the associations of interest. Therefore, our models included interactions between DUI history and a variable that distinguished participants who had prior arrests or convictions for non-DUI crimes from those who did not. We present separate HRs for associations with DUI convictions in the presence or absence of non-DUI criminal history as well as associations with non-DUI criminal history alone and the combination of DUI convictions and non-DUI criminal history. In separate models, we included additional interaction terms with race/ethnicity and sex to test whether associations differed across subgroups.

All covariates described above were hypothesized to have an association with risk of DUI conviction and future arrest for a violent crime, or simply with future arrest for a violent crime, and were included in all adjusted models. We also explored more parsimonious models that included all individual level variables, community characteristics with P < .25 in the model of arrest for any violent crime, and, for conceptual reasons, county violent crime rate. We included community variables as time-varying covariates (except for firearm ownership prevalence), updated in 2005 and 2010 to account for participants relocating and changes within a community over time. We used graphs of Schoenfeld residuals to assess the proportional hazards assumption (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The plotted residuals remained moderately flat over time, suggesting that this assumption was met.

We graphed Kaplan-Meier curves of our primary and 2 secondary outcomes stratified by conviction history at the time of purchase. We used Kaplan-Meier analyses to calculate absolute differences in the probability of arrest for our 3 outcomes at 5 and 12 years after purchase, comparing those with and without a DUI conviction at the time of first purchase in 2001.

Statistical significance was assessed at the 0.05 level (2-sided). Analyses were conducted using SAS software, versions 9.3 and 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Sensitivity and Supplemental Analyses

We tested the sensitivity of our results to changes in criminal history event coding by excluding crimes that were regularly removed from criminal records by the CA DOJ (eg, pre-1976 possession of marijuana) and procedural charges (eg, probation violations, contempt of court) in defining the presence or absence of criminal history. Separately, we included 249 participants with no recent criminal history for whom paper records possibly containing early (pre-1976) criminal events could not be located as having no criminal history. We also compared results using annual updates for the time-varying covariates. Finally, we tested for whether associations differed between first-time and repeat purchasers, and for a dose-response relationship between the number of DUI convictions purchasers had prior to handgun purchase and each outcome.

Results

Data from DROS suggested that 2001 was a typical year. The sales volume of handguns in 2001 (160 619) was close to the mean volume during 1996 to 2005 (181 877 [range, 126 233-244 569]).

Study Population

The study population comprised 79 678 handgun purchasers (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). In all, 13 292 handgun purchasers (16.7%) had prior arrests or convictions at the time of purchase and 1511 (1.9%) had prior DUI convictions (1.6% had 1 and 0.3% had ≥2) (Table 1). Ninety-five purchasers (0.1%) had no DUI convictions but had convictions for other alcohol-related crimes, and 7663 (9.6%) had convictions unrelated to alcohol. After exclusions, the analytic sample included 78 878 purchasers with nonmissing race/ethnicity and community-level data for their residence in 2001, 2005, or 2010. Of them, 65 387 (82.9%) resided in California through the end of the observation period. The purchasers were under observation for 10 738 253 person-months, with those residing in California through December 2013 accounting for 9 742 573 person-months and those censored earlier for 995 680 person-months. The median age of the study participants was 34 (range, 21-49) years. The participants included 72 522 males (91.0%) and 7156 females (9.0%), were predominantly white individuals (54 868 [68.9%]) (Table 1), and resided largely in urban areas (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Distributions of measured variables did not differ meaningfully between the eligible study population and the analytic sample (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of California Handgun Purchasers in 2001.

| Characteristic | Handgun Purchasers, No. (%) (N = 79 678) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 34 (21-49) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 7156 (9.0) |

| Male | 72 522 (91.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| American Indian | 479 (0.6) |

| Asian | 6405 (8.0) |

| Black | 4298 (5.4) |

| Latino | 12 190 (15.3) |

| Other | 1409 (1.8) |

| White | 54 868 (68.9) |

| First-time buyer | 42 241 (53.0) |

| Prior arrests or convictions | 13 292 (16.7) |

| Prior DUI convictions | |

| 1 | 1274 (1.6) |

| 2 | 192 (0.2) |

| ≥3 | 45 (0.1) |

Abbreviation: DUI, driving under the influence.

DUI Conviction and Violent Crimes

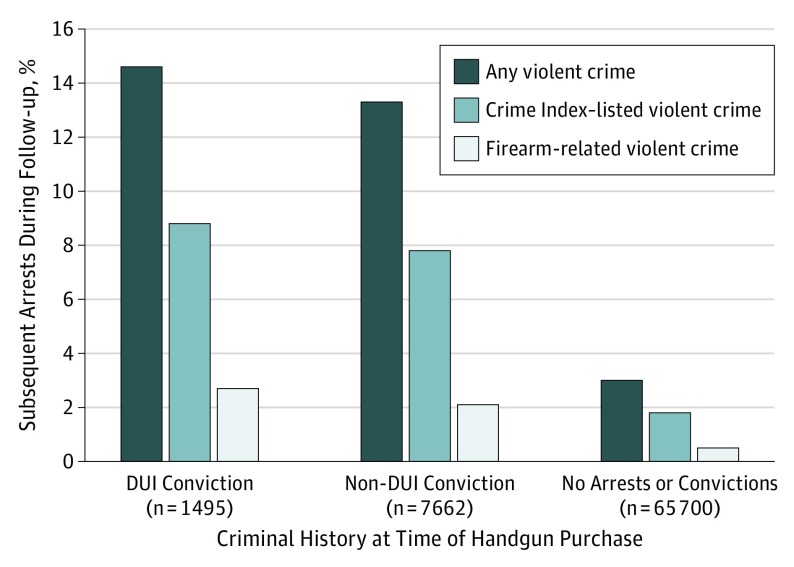

Of 1495 purchasers with prior DUI convictions, 131 (8.8%) were subsequently arrested for Crime Index–listed violent crimes (20 of 404 [5.0%] with DUI convictions and no non-DUI arrests or convictions and 111 of 1091 [10.2%] who had both DUI and non-DUI arrests or convictions) (Figure 1). Among 65 700 purchasers with no prior criminal history, 1188 (1.8%) were subsequently arrested for Crime Index–listed violent crimes, and among 10 771 with only non-DUI arrests or convictions, 816 (7.6%) were.

Figure 1. Subsequent Arrests for Violent Crimes During Follow-up Period, Stratified by Criminal History at the Time of Purchase.

The analytic sample included 78 878 purchasers after exclusions. A total of 136 purchasers with no follow-up information, 635 with no census tract information for the entire follow-up period, and 29 with missing race or ethnicity have been excluded from the figure. Those arrested but not convicted for the crimes of interest at baseline are not shown. Purchasers may appear in both the DUI (driving under the influence) and non-DUI conviction categories.

In adjusted comparisons, purchasers with DUI convictions and no non-DUI arrests or convictions had more than double the risk of arrest for a Crime Index–listed crime compared with purchasers who had no criminal history (AHR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.7-4.1) (Table 2). Among purchasers with prior non-DUI arrests or convictions, DUI convictions remained associated with subsequent arrest for Crime Index–listed violent crimes (AHR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.7).

Table 2. Risk of Subsequent Arrest Associated With Convictions for Driving Under the Influence (DUI) Prior to Handgun Purchasea.

| Conviction | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crime Index–Listed Violent Crime |

Firearm-Related Violent Crime |

Any Violent Crime |

|

| DUI alone | |||

| Purchasers with only DUI convictions vs purchasers with no criminal historyc | 2.6 (1.7-4.1) | 2.8 (1.3-6.4) | 3.3 (2.4-4.5) |

| Other crime alone | |||

| Purchasers with only non-DUI arrests or convictions vs purchasers with no criminal historyc,d | 4.3 (3.9-4.8) | 3.7 (3.0-4.5) | 4.5 (4.1-4.8) |

| DUI and other crime combined | |||

| Purchasers with both DUI convictions and non-DUI arrests or convictions vs purchasers with no criminal historyc | 5.9 (4.9-7.2) | 6.1 (4.2-8.8) | 5.9 (5.0-6.9) |

| DUI if other crime | |||

| Purchasers with both DUI convictions and non-DUI arrests or convictions vs purchasers with only non-DUI arrests or convictionsc | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) |

People with arrests but no convictions for DUI were identified separately in the statistical model, and results are presented in eTable 5 in the Supplement.

Results are adjusted for sex; age; race/ethnicity; number of handguns purchased from 1985 until the index purchase; time elapsed between the most recent DUI- and non–DUI-related arrest events and the index purchase; census tract population size, population density, proportion of persons aged 20 to 44 years who were aged 20 to 24 years, percentage of males, percentage of Latino individuals, percentage of black individuals, alcohol outlet densities, and socioeconomic status index; and county population, violent and property crime rates, and firearm suicides as a proportion of total suicides.

Only DUI convictions implies DUI convictions only and no other arrests or convictions. No criminal history means no arrests or convictions of any kind. Only non-DUI arrests or convictions refers to arrests or convictions for non-DUI crimes and no arrests or convictions for DUI. Both DUI convictions and non-DUI arrests or convictions refers to DUI convictions and arrests or convictions for non-DUI crimes.

Non-DUI crimes include other alcohol-related crimes.

Most participants (75 [57.3%]) with a DUI conviction and a subsequent arrest for a Crime Index–listed violent crime also had prepurchase convictions for non-DUI crimes, and an additional 36 (27.5%) had arrests without convictions. The combination of preexisting DUI convictions and non-DUI criminal history was associated with the greatest risk of subsequent arrest for a Crime Index–listed violent crime (AHR, 5.9; 95% CI, 4.9-7.2) (Table 2).

A history of DUI conviction was also associated with an increased risk of arrest for a firearm-related violent crime and for any violent crime irrespective of whether the participants had preexisting arrests or convictions for non-DUI crimes. Compared with purchasers who had no prior criminal history, those with prior DUI convictions and no other criminal history were at increased risk of arrest for a firearm-related violent crime (AHR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.3-6.4) and any violent crime (AHR, 3.3; 95% CI, 2.4-4.5) (Table 2).

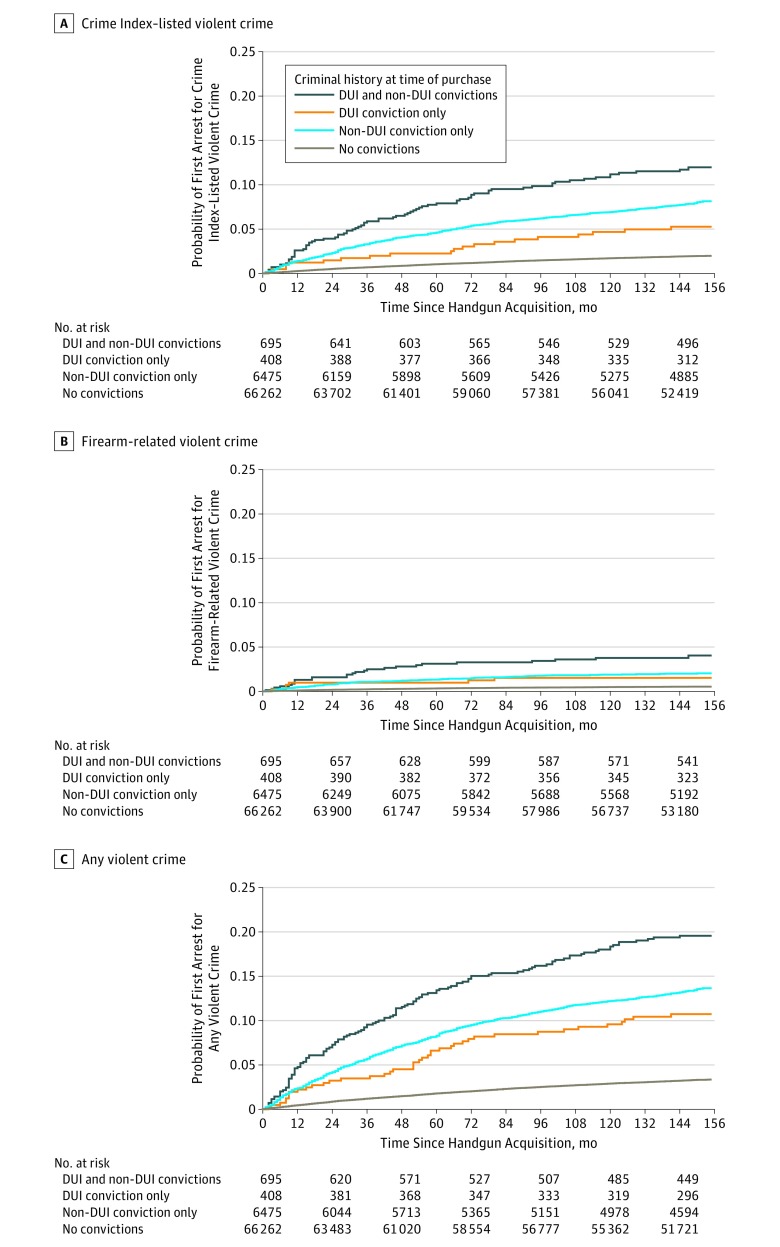

Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary and 2 secondary outcomes stratified by conviction history at purchase are shown in Figure 2; absolute differences calculated from our Kaplan-Meier analyses are shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement. As an example, comparing those with and without a DUI conviction at the time of purchase, the difference in the probability of arrest for a Crime Index–listed violent crime after 12 years was 0.07 (95% CI, 0.05-0.08).

Figure 2. Time to First Arrest for a Violent Crime After Handgun Acquisition Stratified by Conviction History at the Time of Purchase.

The figure excludes purchasers arrested but not convicted for DUI (driving under the influence) or non-DUI crimes at baseline.

Interactions Between DUI History, Race/Ethnicity, and Sex

We found no statistically significant interactions between DUI history and race/ethnicity or sex (Table 3). A statistically significant interaction would suggest that the association between DUI history and arrest for a violent crime differs, on average, depending on the race/ethnicity or sex of the individual.

Table 3. Risk of Subsequent Arrest Associated With a DUI Conviction Prior to Handgun Purchase: Interactions With Race/Ethnicity and Sex.

| Characteristic | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crime Index-Listed Violent Crime | Firearm-Related Violent Crime | Any Violent Crime | |

| DUI Alone, Purchasers With Only DUI Convictions vs Purchasers With No Criminal History b | |||

| Overallc | 2.6 (1.7-4.1) | 2.8 (1.3-6.4) | 3.3 (2.4-4.5) |

| Female | 3.5 (1.2-10.4) | 7.7 (1.5-40.2) | 3.7 (1.5-8.8) |

| Male | 2.6 (1.7-4.0) | 2.7 (1.2-6.1) | 3.3 (2.4-4.4) |

| American Indian | 2.3 (0.5-10.8) | NAd | 2.6 (0.7-8.9) |

| Asian | 4.6 (1.7-12.2) | 10.2 (2.6-40.2) | 3.1 (1.2-7.8) |

| Black | 2.1 (1.0-4.4) | 2.8 (0.8-9.6) | 2.7 (1.5-4.8) |

| Latino | 1.8 (1.0-3.1) | 1.1 (0.3-3.6) | 2.5 (1.7-3.7) |

| Other race | 2.3 (0.5-10.1) | 3.0 (0.3-26.9) | 3.6 (1.3-10.6) |

| White | 3.2 (2.0-5.1) | 3.5 (1.5-8.4) | 3.9 (2.8-5.4) |

| DUI if Other Crime, Purchasers With Both DUI Convictions and Non-DUI Arrests or Convictions vs Purchasers With Only Non-DUI Arrests or Convictions b , e | |||

| Overallc | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) |

| Female | 1.8 (0.7-5.1) | 4.6 (1.0-21.1) | 1.5 (0.6-3.4) |

| Male | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) |

| American Indian | 1.2 (0.3-5.3) | NA | 1.0 (0.3-3.4) |

| Asian | 2.4 (0.9-6.0) | 6.0 (1.7-21.5) | 1.2 (0.5-3.0) |

| Black | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | 1.6 (0.6-4.1) | 1.1 (0.6-1.7) |

| Latino | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 0.7 (0.3-1.7) | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) |

| Other race | 1.2 (0.3-5.0) | 1.7 (0.2-14.3) | 1.4 (0.5-4.0) |

| White | 1.6 (1.3-2.1) | 2.1 (1.3-3.3) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) |

| DUI interaction with sex, P value | .79 | .42 | .83 |

| DUI interaction with race/ethnicity, P value | .44 | .24 | .46 |

Abbreviations: DUI, driving under the influence; NA, not applicable.

Models for race-specific effects included 2-way interactions between DUI criminal history, non-DUI criminal history, and race or ethnicity; models for sex-specific effects included 2-way interactions between DUI criminal history, non-DUI criminal history, and sex. Results are adjusted for sex; age; race or ethnicity; number of handguns purchased from 1985 until the index purchase; time elapsed between the most recent DUI and non–DUI related arrest events and the index purchase; census tract population size, population density, proportion of persons aged 20 to 44 years who were aged 20 to 24 years, percentage of males, percentage of Latino individuals, and percentage of black individuals, alcohol outlet densities, and socioeconomic status index; and county population, violent and property crime rates, and firearm suicides as a proportion of total suicides. People with arrests but no convictions for DUI were identified separately in the statistical model and the results are not shown.

Refer to footnote c in Table 2 for definitions.

Overall results are reproduced for comparison.

None of the 13 American Indian purchasers with a DUI conviction were arrested for a firearm-related violent crime; it was not possible to estimate these hazard ratios and confidence intervals.

Non-DUI crimes include other alcohol-related crimes.

Supplemental Analyses

We found no evidence of a difference in the associations between first-time and repeat purchasers or of a dose-response relationship between the number of prior DUI convictions and the risk of subsequent arrest for a Crime Index–listed violent crime (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement). The results of analyses examining the slightly broader category of alcohol-related crimes as the exposure or exchanging convictions for arrests as the outcome were largely consistent with those in the primary analyses (eTable 5 in the Supplement). The sensitivity analyses had consistent results (eTables 6 and 7 in the Supplement) as did more parsimonious models that included fewer variables (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this population of authorized purchasers of handguns in California, a history of DUI conviction at the time of purchase was found to be associated with a significant increase in the risk of subsequent arrest for a Crime Index–listed violent crime, a firearm-related violent crime, and any violent crime independent of a range of individual and community-level measures. Participants with both a history of DUI conviction and other preexisting non-DUI arrests or convictions were at greatest risk of subsequent arrest for a violent crime. Among those who had arrests or convictions for non-DUI crimes, the HRs associated specifically with DUI convictions were smaller. This finding suggests that a DUI conviction prior to the time of purchase offers a relatively modest increase in explanatory power over a history of arrests or convictions.

Our findings are consistent with those of studies among more general populations, which show that alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of violence perpetration30,31,32; our study extends those findings specifically to legal purchasers of handguns. Our previous study involved handgun purchasers from 1977, prior to the extension of California’s prohibiting criteria for firearm ownership to those with convictions for violent misdemeanors in 1991. The basic findings of the 2 studies, however, are similar, and we have now analyzed more recent data in a much larger study population.

As in the prior study,16 we did not find a dose-response relationship between the number of prior DUI convictions and the risk of subsequent arrest for a Crime Index–listed violent crime. This result contrasts with previous research on criminal activity among DUI offenders.33,34,35,36,37,38 Prior studies, however, often compared the prior criminal histories of first-time and repeat DUI offenders. Our study sample was distinct in that participants with prior DUI convictions could not also have been convicted of a felony or, within 10 years of purchase, of certain violent misdemeanors; those convictions would have prohibited them from purchasing firearms legally in California. Among DUI offenders in general, the presence of other criminal history may be associated with an increased risk for future criminal activity39; selection criteria associated with legal handgun purchase in California are a possible reason why we did not find a dose-response relationship.

Alternatively, the absence of a dose-response relationship may reflect the finding that even 1 DUI conviction suggests a sustained pattern of risky behavior; DUI offenders are estimated to drive while impaired from 200 to 2000 times before their first arrest.37 In a longitudinal study, the DUI recidivism rate of first-time offenders more closely resembled that of repeat offenders than the first-offense rate of nonoffenders,37 a finding similar to ours that is aligned with this alternative hypothesis.

The bar for firearm ownership is particularly high in California; firearm purchasers must have no convictions for a wide range of violent misdemeanors in the 10 years prior to purchase. As a result, many individuals with a higher likelihood of violence perpetration were likely excluded from our sample. Assuming that DUI conviction history and violent misdemeanor conviction history are associated, the risk for future violence among firearm owners with DUI convictions may be even greater in the 25 states where individuals with violent or firearm-related misdemeanor convictions remain eligible to purchase firearms.40

Finally, of note, the risk of arrest and conviction given criminal behavior is not uniformly distributed across the population, and some subgroups, such as specific racial groups, may be over- or underrepresented in the criminal history data for reasons other than their propensity to drive while impaired, such as enforcement behavior.41,42 In the present study, we found no evidence to suggest that DUI conviction is a nonuniform marker of risk for future violence across specific races/ethnicities or by sex.

Limitations

Our study relied on criminal records to identify risky alcohol use and violent behavior. Violence prevention policy often relies on such administrative records, making this practice a useful approach. However, convictions are several steps removed from behavior, and, as noted previously, DUI convictions are rare compared with self-reported rates of alcohol-impaired driving. We were unable to study associations between other forms of risky alcohol use, such as binge drinking, and violence in our study population. The exclusion of purchasers older than 50 years limits the generalizability of our results. California’s violent misdemeanor prohibition discussed above may also limit the generalizability of our results to states without this prohibition, as may other differences in firearm policy (eg, states without comprehensive background check policies). Finally, between 1959 and 2014, California’s definition of DUI included impairment by alcohol, drugs, or any combination of the two.43 However, annual reports on California DUIs beginning in 1991 show that at least 97.0% of DUI crimes involved blood alcohol concentrations above 0.08% (80 ng/dL).

Conclusions

This longitudinal study of handgun purchasers in California, who were followed up from 10 days after purchase in 2001 through 2013, found that a history of DUI conviction is associated with a substantially higher risk of subsequent arrest for a range of violent crimes. Although the elevated risk was diminished, it remained even among participants with a history of arrests or convictions for crimes of other types.

The federal government and many states have restricted the purchase and possession of firearms by members of high-risk groups, including persons convicted of felonies, domestic violence misdemeanors, and other violent misdemeanors. The available evidence suggests that such policies may reduce the incidence of violent criminal activity among persons whose access to firearms is restricted.44,45,46,47,48 Our findings suggest that comparable benefits may arise from similar restrictions on persons convicted of DUI crimes.

eAppendix 1. Linking Methods

eAppendix 2. Socioeconomic Index

eFigure 1. Graphs of Schoenfeld Residuals for Each Exposure Combination and Each Outcome

eFigure 2. Flow Chart for Analytic Sample

eFigure 3. Purchaser Locations [A] and Purchaser Density per 1000 by Census Tract [B] in 2001

eTable 1. Comparison of Eligible Study Population and Analytic Sample Across a Range of Variables

eTable 2. Absolute Differences in Probability of Arrest at 5 and 12 Years Associated With DUI Conviction at Purchase

eTable 3. Hazard Ratios for Arrest for Violent Crime Index Crimes Among First-time and Repeat Purchasers

eTable 4. Hazard Ratios for Arrest for Violent Crime Index Crime by Number of DUI Convictions Prior to Index Purchase in 2001

eTable 5. Risk of Arrest or Conviction Associated With DUI and Alcohol-Related Arrests or Convictions

eTable 6. Risk of Arrest Associated With DUI and Alcohol-Related Arrests or Convictions, Including 249 Individuals With Missing Criminal History Data

eTable 7. Risk of Arrest Associated With DUI and Alcohol-related Arrests or Convictions, Excluding Purged and Procedural Crimes

eTable 8. Risk of Subsequent Arrest Associated With DUI Conviction Prior to Handgun Purchase: Partially Adjusted

References

- 1.Fatal injury reports, national, regional, and state, 1981-2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html. Updated January 18, 2019. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 2.Morgan R, Truman J. Criminal Victimization, 2017. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Dept of Justice; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branas CC, Han S, Wiebe DJ. Alcohol use and firearm violence. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):32-45. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wintemute GJ. Alcohol misuse, firearm violence perpetration, and public policy in the United States. Prev Med. 2015;79:15-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonard KE. The role of drinking patterns and acute intoxication in violent interpersonal behaviors. In: Grant M, Fox M, Leonard K, O’Conner C, eds. Alcohol Violence: Exploring Patterns and Responses. Washington, DC: International Center for Alcohol Policies; 2008:29-55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wintemute GJ. Association between firearm ownership, firearm-related risk and risk reduction behaviours and alcohol-related risk behaviours. Inj Prev. 2011;17(6):422-427. doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.031443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhns JB, Exum ML, Clodfelter TA, Bottia MC. The prevalence of alcohol-involved homicide offending: a meta-analytic review. Homicide Stud. 2013;18(3):251-270. doi: 10.1177/1088767913493629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckhardt CI, Parrott DJ, Sprunger JG. Mechanisms of alcohol-facilitated intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(8):939-957. doi: 10.1177/1077801215589376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr BG, Porat G, Wiebe DJ, Branas CC. A review of legislation restricting the intersection of firearms and alcohol in the U.S. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(5):674-679. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohio Rev Code Article 2 §137.21.

- 11.Tennessee Code §39-17-1316.

- 12.Cal Welf & Inst Code §8103(f).

- 13.Cal Penal Code §29805.

- 14.Cal Leg, S 755 Firearms—prohibited persons, Regular Sess (2013-2014).

- 15.SB 755 veto message [press release]. 2013.

- 16.Wintemute GJ, Wright MA, Castillo-Carniglia A, Shev A, Cerdá M. Firearms, alcohol and crime: convictions for driving under the influence (DUI) and other alcohol-related crimes and risk for future criminal activity among authorised purchasers of handguns. Inj Prev. 2018;24(1):68-72. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Federal Bureau of Investigation . Uniform Crime Reporting Handbook. Clarksburg, WV: US Dept of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wintemute GJ, Kass PH, Stewart SL, Cerdá M, Gruenewald PJ. Alcohol, drug and other prior crimes and risk of arrest in handgun purchasers: protocol for a controlled observational study. Inj Prev. 2016;22(4):302-307. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeber R, Farrington DP. Age-crime curve. In: Bruinsma G, Weisburd D, eds. Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2014:12-18. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-5690-2_474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herzog TN, Scheuren FJ, Winkler WE. Data Quality and Record Linkage Techniques. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bureau of Justice Statistics . Survey of State Criminal History Information Systems, 2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Federal Bureau of Investigation . 2019 National Incident-Based Reporting System User Manual. Clarksburg, WV: US Dept of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Definition and typology of violence. Violence Prevention Alliance website. https://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/definition/en/. Published 2019. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 24.Geolytics Estimates Premium [DVD-ROM]. East Brunswick, NJ: Geolytics Inc; 2013.

- 25.American Community Survey. US Census Bureau website. http://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/. Accessed October 26, 2016.

- 26.2019 Priority application announcement. California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control website. https://www.abc.ca.gov. Accessed January 2, 2013.

- 27.Uniform Crime Reporting Program . Jurisdiction level reports for California, 2000-2013 [obtained by request]. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azrael D, Cook PJ, Miller M. State and local prevalence of firearms ownership measurement, structure, and trends. J Quant Criminol. 2004;20(1):43-62. doi: 10.1023/B:JOQC.0000016699.11995.c7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Death statistical master file, 2001-2015 [obtained by request]. Sacramento: California Dept of Public Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Alcohol misuse and criminal offending: findings from a 30-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128(1-2):30-36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Alcohol misuse and violent behavior: findings from a 30-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(1-2):135-141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller PG, Butler E, Richardson B, et al. Relationships between problematic alcohol consumption and delinquent behaviour from adolescence to young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35(3):317-325. doi: 10.1111/dar.12345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucker GW, Kruzich DJ, Holt MT, Gold JD. The prevalence of antisocial behavior among U.S. Army DWI offenders. J Stud Alcohol. 1991;52(4):318-320. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gould LA, Gould KH. First-time and multiple-DWI offenders: a comparison of criminal history records and BAC levels. J Crim Justice. 1992;20(6):527-539. doi: 10.1016/0047-2352(92)90062-E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMillen DL, Adams MS, Wells-Parker E, Pang MG, Anderson BJ. Personality traits and behaviors of alcohol-impaired drivers: a comparison of first and multiple offenders. Addict Behav. 1992;17(5):407-414. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90001-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hallstone M. Types of crimes committed by repeat DUI offenders. Crim Justice Stud. 2014;27(2):159-171. doi: 10.1080/1478601X.2014.896800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rauch WJ, Zador PL, Ahlin EM, Howard JM, Frissell KC, Duncan GD. Risk of alcohol-impaired driving recidivism among first offenders and multiple offenders. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):919-924. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dugosh KL, Festinger DS, Marlowe DB. Moving beyond BAC in DUI: identifying who is at risk of recidivating. Criminol Public Policy. 2013;12(2):181-193. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LaBrie RA, Kidman RC, Albanese M, Peller AJ, Shaffer HJ. Criminality and continued DUI offense: criminal typologies and recidivism among repeat offenders. Behav Sci Law. 2007;25(4):603-614. doi: 10.1002/bsl.769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Categories of prohibited people. Gifford’s Law Center website. https://lawcenter.giffords.org/gun-laws/policy-areas/who-can-have-a-gun/categories-of-prohibited-people/. Accessed January 5, 2018.

- 41.Mauer M, King RS. Uneven Justice: State Rates of Incarceration by Race and Ethnicity. Washington, DC: Sentencing Project; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piquero AR. Disproportionate minority contact. Future Child. 2008;18(2):59-79. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cal Vehicle Code § 23102.

- 44.Wintemute GJ, Wright MA, Drake CM, Beaumont JJJJ. Subsequent criminal activity among violent misdemeanants who seek to purchase handguns: risk factors and effectiveness of denying handgun purchase. JAMA. 2001;285(8):1019-1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright MA, Wintemute GJ, Rivara FP. Effectiveness of denial of handgun purchase to persons believed to be at high risk for firearm violence. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(1):88-90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.1.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swanson JW, Robertson AG, Frisman LK, et al. Preventing gun violence involving people with serious mental illness. In: Webster D, Vernick J, eds. Reducing Gun Violence in America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swanson JW, McGinty EE, Fazel S, Mays VM. Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(5):366-376. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swanson JW, Easter MM, Robertson AG, et al. Gun violence, mental illness, and laws that prohibit gun possession: evidence from two Florida counties. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(6):1067-1075. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Linking Methods

eAppendix 2. Socioeconomic Index

eFigure 1. Graphs of Schoenfeld Residuals for Each Exposure Combination and Each Outcome

eFigure 2. Flow Chart for Analytic Sample

eFigure 3. Purchaser Locations [A] and Purchaser Density per 1000 by Census Tract [B] in 2001

eTable 1. Comparison of Eligible Study Population and Analytic Sample Across a Range of Variables

eTable 2. Absolute Differences in Probability of Arrest at 5 and 12 Years Associated With DUI Conviction at Purchase

eTable 3. Hazard Ratios for Arrest for Violent Crime Index Crimes Among First-time and Repeat Purchasers

eTable 4. Hazard Ratios for Arrest for Violent Crime Index Crime by Number of DUI Convictions Prior to Index Purchase in 2001

eTable 5. Risk of Arrest or Conviction Associated With DUI and Alcohol-Related Arrests or Convictions

eTable 6. Risk of Arrest Associated With DUI and Alcohol-Related Arrests or Convictions, Including 249 Individuals With Missing Criminal History Data

eTable 7. Risk of Arrest Associated With DUI and Alcohol-related Arrests or Convictions, Excluding Purged and Procedural Crimes

eTable 8. Risk of Subsequent Arrest Associated With DUI Conviction Prior to Handgun Purchase: Partially Adjusted