Abstract

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a clinical syndrome characterized by left ventricular dilatation and contractile dysfunction. It is the most common cause of heart failure in young adults. The advent of next-generation sequencing has contributed to the discovery of a large amount of genomic data related to DCM. Mutations involving genes that encode cytoskeletal proteins, the sarcomere, and ion channels account for approximately 40% of cases previously classified as idiopathic DCM. In this scenario, geneticists and cardiovascular genetics specialists have begun to work together, building knowledge and establishing more accurate diagnoses. However, proper interpretation of genetic results is essential and multidisciplinary teams dedicated to the management and analysis of the obtained information should be considered. In this review, we approach genetic factors associated with DCM and their prognostic relevance and discuss how the use of genetic testing, when well recommended, can help cardiologists in the decision-making process.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Dilated/genetics; Ventricular Dysfunction, Left; Heart Failure; Genetic Testing/methods; Heart Transplantation

Introduction

Primary cardiomyopathies (PCMs) are a heterogeneous group composed predominantly by genetic diseases associated with pathological alterations of myocardial structure and function.1-3 These diseases often progress to heart failure (HF), with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) being the main indication for heart transplantation (HTx).3 Currently, the prevalence of idiopathic DCM is estimated at around 1 case per 2,500 population, but authors such as Hershberger et al.4 describe a frequency ten times greater.4 Particularly in the last two decades, a greater understanding on the etiology and clinical course of many of these diseases has been achieved.5,6 This has been possible by substantial advances in the use of genetic diagnosis at cardiomyopathy clinics and research centers around the world.

Traditionally, DCM is defined as dilatation of the left ventricle or both ventricles, with consequent impairment in myocardial contractility, in the absence of abnormal overload and/or ischemic heart disease.4-6 However, this syndrome can encompass a wide range of genetic and acquired disorders that can be expressed to a greater or lesser impact over the patient’s life course. Some individuals with specific mutations detected in the early DCM-stages may present intermediate phenotypes that do not meet the classical definition of the disease.2,4 For this reason, the formulation of some concepts that define subgroups of patients with this syndrome would be relevant, such as the case of hypokinetic non-DCM,2 where systolic dysfunction may occur without left ventricular dilatation. In fact, the observed clinical heterogeneity is the partial reflex of the various genes related to sarcomere proteins, cytoskeleton, intercellular connections, the cell membrane, and ion channels (Table 1),2,4,7,8 which have been implicated in DCM. Many of these genes have been also associated with other forms of cardiomyopathies (left ventricle non-compaction [LVNC], arrhythmogenic, hypertrophic, and restrictive), and the prevalence of pathogenic variants in each of these genes is distinct for each disorder.4,7 Mutations with pathogenic potential are identified in up to 40% of cases described as idiopathic DCM, depending on the cohort.9,10 Indeed, it has been suggested that genetic testing would have a higher yield (up to 70%) in cohorts of patients with idiopathic DCM already waitlisted for HTx.11,12

Table 1.

Main genes associated with dilated cardiomyopathy

| Gene | Protein | Estimated contribution |

Association with other cardiomyopathies |

Other phenotypes | Inheritance | Level of evidence* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarcomere | ||||||

| TTN | Titin | 18-25% | LVNC | Myopathies | AD | 1 |

| TNNT2 | Troponin T type 2 | 2-3% | HCM, LVNC | - | AD | 1 |

| TNNI3 | Troponin I3, cardiac type | 1-2% | HCM, RCM | - | AR | 1 |

| TPM1 | Tropomyosin 1 | 1-2% | HCM, LVNC | Congenital heart disease | AD | 1 |

| MYH7 | Miosina-7 (beta-myosin heavy chain) | 3-5% | HCM, LVNC | Myopathies | AD | 1 |

| MYBPC3 | Myosin-binding protein C | 2% | HCM, LVNC | - | AD | 1 |

| BAG3 | Bcl-2-associated athanogene 3 | 2% | - | Myofibrillar myopathy | AD | 1 |

| ACTC1 | Actin alpha cardiac muscle 1 | <1% | HCM, LVNC | - | AD | 1 |

| Cytoskeleton | ||||||

| ACTN2 | Actin alpha cardiac muscle 2 | < 1% | HCM | Congenital heart disease | AD | 2 |

| FLNC | Filamin C | 2.2% | HCM, RCM | - | 1 | |

| LDB3 | LIM domain binding 3 | <1% | NA | Myofibrillar myopathy | AD | 2 |

| ANKRD1 | Ankyrin repeat domain 1 | < 1% | HCM | Congenital heart disease | AD | 3 |

| VCL | Vinculin | 1% | NA | - | AD | 3 |

| JUP | Junction plakoglobin | 1 % | ACM | Naxos disease | AD/AR | 1 |

| DMD | Dystrophin | 1% | NA | Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy |

X-linked | 1 |

| DES | Desmin | 1-2% | HCM, RCM | Myofibrillar myopathy | AD | 1 |

| Cell Membrane | ||||||

| LMNA | Lamin A/C | 5-10% | HCM | Muscle myopathies, lipodystrophies, progeria |

AD | 1 |

| EMD | Emerin | NA | ACM | Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy |

X-linked | 1 |

| Ion Channels | ||||||

| SCN5A | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 5 |

2-3% | LVNC | Brugada syndrome/LQTS | AD | 1 |

| ABCC9 | ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 9 |

< 1% | - | Osteochondrodysplasia | AD | 3 |

| Desmosome | ||||||

| DSC2 | Desmoscollin-2 | 1-2% | ACM | Palmoplantar keratoderma |

AD | 1 |

| DSG2 | Desmoglein 2 | 1-2% | ACM | - | AD/digenic | 1 |

| DSP | Desmoplakin | 3% | ACM | Carvajal syndrome | AR | 1 |

| PKP2 | Plakophilin 2 | <5% | ACM | - | AD | 1 |

| Lysosome | ||||||

| LAMP2 | Lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 |

4% | HCM | Danon disease | X-linked | 1 |

|

Sarcoplasmic Reticulum |

||||||

| PNL | Phospholamban | 1% | HCM, ACM | - | AD | 1 |

| RYR2 | Ryanodine receptor 2 | NA | - | CPVT | AD | 2 |

| RBM20 | RNA binding motif protein 20 | 2% | LVNC | - | AD | 1 |

HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; RCM: restrictive cardiomyopathy; LVNC: Left ventricle non-compaction cardiomyopathy; ACM: arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy; CPVT: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; LQTS: long QT syndrome; NA: not available; AD: autosomal dominant; AR: autosomal recessive.

The genes were classified according to three levels.

Level 1: Multiple studies, variants and families reported and cosegregation with established disease. Level 2: Single or few studies, variants and families reported and limited cosegregation observed. Level 3: Single or few studies, variants and families reported and unestablished cosegregation.

In the last decade, recommendations for the use of genetic testing in familial DCM have been established by respective guidelines.9 Genetic testing can help in the management of patients and their relatives, as well as optimize the risk stratification. Careful clinical evaluation, a thorough family history, and the results of genetic testing are the cornerstones of this approach. Considering the incipient use of genetics in DCM management in Brazil, the aim of this review is to present and discuss the importance of molecular testing in the DCM spectrum.

Methods for genetic diagnosis in dilated cardiomyopathy

The use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms has enabled two approaches for the genetic diagnosis of DCM:

Whole-exome sequencing: this approach covers “all” exons and flanking regions of the human genome (in practice, it considers only those genes for which correlated clinical information already exists). Exome sequencing has been more used in applied clinical research, resulting in the discovery of new genes potentially associated with DCM.13,14 These “new” genes are also called candidate genes because the level of evidence supporting its pathogenic potential is still low or uncertain. It would result in a greater number of unknown clinical significance variants;

Targeted NGS: NGS panels sequence a certain number of genes for which there is higher evidence of a causal association with DCM (Table 1).15,16 The large volume of cases already described in carriers of pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in these genes raised useful information for clinical decision-making;17 it is important to emphasize that most of the mutations reported in DCM are exclusive to a single family, which leads to barriers in the interpretation of the genetic data. Therefore, integration of clinical manifestations and family history is essential in the decision-making process.17 There are around a hundred genes associated with DCM, with different levels of evidence for their associations. Furthermore, it bears stressing that the presence of a genetic mutation does not always mean that the disease will develop.18 The best-documented genes are listed in Table 1.

In recent years, the increasingly widespread use of NGS panels has allowed the identification of a significant number of individuals with variants in the same gene. This population has been enabling relevant clinical descriptions in DCM, as in the most recent studies addressing different genes (TTN, LMNA, FLNC, or BAG3).19-21 Cosegregation of variants in these genes has been demonstrated as disease-causing in multiple DCM-families, and the ever-increasing number of identified carriers has enabled genotype-phenotype correlation analyses on the prognosis of the disease.22,23

Briefly, genetic testing through the aforementioned techniques can help cardiologists in three important clinical scenarios:8-10,24,25

familial management;

etiological definition and;

assertive risk stratification.

Importance of family screening in dilated cardiomyopathy

A cohort study with advanced HF patients waiting in the transplant list shows that the diagnosis of familial DCM (FDCM) was systematically neglected.26 The mere use of the pedigree tool increased the prevalence of this diagnosis from 4.1%to 26%. Prospective cohorts have since found that 25 to 40% of non-ischemic DCM cases are in fact familial,9,24 drawing attention to the hereditary component of this syndrome, as well as to the importance of early detection and treatment of affected relatives. In this context, pedigree with at least three generations and the use of genetic testing is strongly recommended.9

The identification of a pathogenic or a likely pathogenic variant in an index case (proband) allows the entire family of the patient may benefit from genetic screening.4,9 This is particularly useful in cases where clinical evaluation alone has not been able to establish the diagnosis in a relative.2,4 In addition, the early identification of a family member carrier who is asymptomatic, or in the subclinical phase of the disease, may be particularly relevant when genetic testing reveals etiologies with greater arrhythmogenic potential or known to evolve faster.19,20 Moreover, in this scenario, it would be possible to apply measures to delay disease progression or even avert a fulminant outcome. On the other hand, regular follow-up of the index case's relatives that are identified as non-carriers of a pathogenic variant is not recommended;9 this avoids unnecessary health expenditures and prevents additional psychological stress to the patient/family.

Etiological definition and associated prognosis

TTN truncating variants: a milestone in knowledge about the role of genetics in DCM was a study by Herman et al.11 In this publication, titin-truncating variants (TTNtv) were identified in 25% of cases of FDCM and in 18% of sporadic DCM-cases. These prevalence were obtained across three different cohorts, with a frequency of TTNtv between 8 and 40%. It is worth noting that higher frequencies were observed in subjects undergoing HTx or with severe systolic dysfunction. Since then, other studies have sought to ascertain the natural history of DCM by assessing TTNtv patients.24,27,28 No difference was observed in the incidence of outcomes among affected carriers vs. non-carriers,27 as there was no difference in mesocardial fibrosis between these groups.28 However, males with TTNtv manifested the disease at younger ages than female carries (78% vs. 30% of women at age 40).27 Other authors have identified that affected TTNtv carriers would have an earlier outcome event (death from any cause, waiting for HTx, or requiring a ventricular-assist device) than non-carriers.28 In this same line, male carriers had a lower survival rate (28% of men had a cardiovascular event vs. 8% of women before age 50), considering the outcomes death by HF, HTx, or use of a ventricular assist device.27

In a robust sample (n = 558), a high incidence of cardiovascular death starting at age 40 years was observed in patients with TTNtv.29 In this cohort, the incidence of cardiovascular events was again higher in men than in women “(1.25% vs. 0.75%/year between the ages of 40-60), with sudden cardiac death being the most frequent outcome. In addition, several publications have described a high incidence of atrial fibrillation, as well as sustained and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, in these patients.24,25,28,30

Although according to the literature, the presence of TTNtv is associated with early onset of arrhythmic manifestations, it has not yet been possible to define a characteristic phenotype for these patients, unlike for patients with mutations in other DCM-related genes. Moreover, it has been proposed that TTNtv may be acting as a susceptibility genetic substrate to different DCM-types (anthracycline-induced, peripartum, and alcoholic).27-29 Finally, patients with titin cardiomyopathy appear to have a more favorable clinical course and respond better to drug therapy than those affected by variants in the lamin (LMNA) gene.31-33

Lamin: LMNA pathogenic variants produce a well-characterized DCM phenotype associated with conduction disease/malignant arrhythmias, also called cardiolaminopathies.34 Phenotypic expression have been described as a progressive atrioventricular conduction disease which usually precedes ventricular dysfunction and/or ventricular arrhythmias, although ventricular or supraventricular arrhythmias (especially atrial fibrillation) may be identified as the first manifestation.19,34 Diagnosis is usually established after age 20, with high penetrance (>90%) after 40 years.35 Once the first symptoms have manifested, cardiolaminopathies can progress to advanced HF faster than primary DCM of other etiologies.19,36LMNA mutations prevalence ranges from 5-10% in FDCM cohorts and 2-5% in sporadic cases, accounting for up to 30% of the DCM-cases associated with conduction disease/arrhythmias. Their prevalence is lower in cases of isolated DCM (non-arrhythmic).34,35

Between 2013 and 2015, Hasselberg et al.37 identified a 6% prevalence of LMNA gene mutations in a cohort of 79 Norwegians young with FDCM. A particularly high proportion of carriers (19%) required HTx. In another study, 122 affected LMNA carriers were followed for seven years; 27 progressed to terminal DCM or death. It is worth noting that, in this same cohort, asymptomatic carriers had a 9% annual incidence of any documented cardiac event over 4 years of follow-up.19 These findings suggest a significant unfavorable prognosis and faster progression to HTx/death than in DCMs with other etiologies.

These clinical and epidemiological profile supports the recommendations for genetic testing of patients with non-ischemic DCM. Furthermore, an early implant of a cardioverter/defibrillator (ICD) should be considered when a LMNA pathogenic variant is identified (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B) in a patient with risk factors.38 Based on the study published in 2012 that enrolled 269 patients with cardiolaminopathy, the risk of cardiac events is highest when the patient has two or more of these risk criteria at the time of diagnosis: 1) non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; 2) left ventricular ejection fraction <45%; 3) male sex; and 4) a truncating-type variant.39 Since then, other authors have proposed that not only truncating variants but also missense-type genetic variants, would be relevant due to the potential for sudden death.40 Finally, a new risk score for patients with DCM associated with LMNA variants should be published soon. We hope that it will increase the accuracy of risk stratification in these patients.

Other genes: Some sarcomere genes more often associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) may also cause DCM.25 The beta-myosin heavy chain (MYH7), troponin T (TNNT2), and tropomyosin (TPM1) sarcomere genes are those for which associated prognostic information is available. Depending on the location of the genetic variant in the MYH7 gene, the natural history may be particularly severe, similarly to that observed occurs in cases of DCM caused by TNNT2 mutations.25TPM1 variants cause less than 1% of DCM cases but account for a significant portion of pediatric forms of this disease, in which rapid progression to death or HTx is not uncommon.25 A meta-analysis of nearly 8,100 patients evaluated genotype-phenotype correlations of DCM with the TTN and LMNA genes, as well as genes encoding sarcomere proteins such as myosin-binding protein C (MYBPC3), MYH7, TNNT2, troponin I (TNNI3), RNA-binding protein 20 (RBM20), and phospholamban (PLN).41 A significantly higher frequency of HTx was observed in patients with LMNA mutations (27%) than for carriers of RBM20 and MYBPC3mutations (~10% each). Across the different genes examined, those affected were predominantly male (79% for MYBPC3 mutations and 69% for LMNA and MYH7 variants), except for PLN mutations (46% men).

More recently, the filamin C (FLNC) and Bcl-2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3) genes have had their role in the DCM natural history characterized in high-impact publications.20,21,42FLNC was associated with a more arrhythmogenic profile, and BAG3, with a greater number of HF-related events. FLNC truncating variants were found cosegregating in 28 affected families with a particular form of arrhythmogenic/DCM.20 The most prevalent clinical features were ventricular dilatation (68%), systolic dysfunction (46%), and myocardial fibrosis (67%). Ventricular arrhythmias were documented in 82% of the patients, and cases of sudden death were reported in 21/28 families. Another study identified FLNC truncation variants in 2.2% of DCM-patients, 85% of whom had ventricular arrhythmias and/or sudden death.42 Additional right-heart involvement was reported in 38% of the cases. Thus, early ICD implantation could be considered in these patients, even when they do not meet the criteria established in current DCM guidelines.9,20

In recent years, several isolated BAG3 reports have been described in DCM-families.43-47 In a meaningful way, BAG3 associated phenotype was recently defined with data from a cohort of 129 carriers.19 After a mean follow-up of 38 months, the number of carriers affected with DCM raised from 57% to 68%. It represents 26% of the carriers who initially had a negative phenotype but manifested the disease. Considering carriers over the age of 40, 80% were phenotype-positive. In this sample, the incidence of cardiac events in carriers of BAG3 variants with DCM was 5.1% per year (outcomes: sustained ventricular tachycardia, sudden death, HF death, need for ventricular assist device and HTx), with a predominance of HF-events versus a lower number of arrhythmic outcomes. Male patients, those with systolic dysfunction, or increased ventricular diameter had the highest incidence of events during the follow-up.21 Based on these findings, variants of the BAG3 gene do not appear to be related to a need for early ICD implantation, unlike FLNC mutations.

Genetic heterogeneity and overlapping phenotype

Many of the genes described as disease-causing in patients with DCM are also associated with the development of other forms of PCMs (Table 1). This fact may result in the presence of more than one phenotype in the same pedigree or overlapping phenotypes in the same individual, as occurs, for example, with LVNC and DCM.48,49

In a cohort of 95 patients with LVNC (68 unrelated individuals and 27 relatives, 23% of cases familial), a genetic variant was identified in 38% of the cases.49 The most frequent genes were TTN, LMNA, and MYBPC3; one family was affected by a RBM20 mutation. In this family, three generations were affected on the maternal side, and the index case underwent to HTx at the age of 21 (3 years after diagnosis). The number of major cardiovascular events in this cohort was significantly higher in patients with LVNC than those probands with non-ischemic DCM of known etiology. Approximately 10% of the patients with LVNC required HTx vs. 2.8% in the non-ischemic DCM group.49 One of the families with LVNC in this cohort was found carrying a MYH7 gene variant which has been associated in different studies with malignant-HCM. Although the affected individuals did not meet definitive criteria for HCM, several had an appreciable increase in myocardial wall thickness.49 This should draw the attention of cardiologists to the phenotypic heterogeneity of PCMs, as well as to the need to bear in mind what an etiological diagnosis can represent in terms of the natural history of the disease.

Genes usually related to arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) may produce indistinguishable clinical phenotype from those with DCM. Patients affected by desmoplakin (DSP) or FLNC truncating variants, for instance, may be affected by a form of ACM with exclusive left ventricle involvement.20,50,51 There are several reports of DCM-patients affected by mutations in desmosomal genes that do not fulfil any (or only some) of the arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia diagnostic criteria.50-52

In a study of 89 unrelated end-stage DCM patients requiring HTx, screening of the five most common desmosomal genes (PKP2, DSP, JUP, DSC2, DSG2) identified genetic variants in 18% of the probands.51 Genetic testing in relatives identified additionally 38 carriers, including some with subclinical DCM. Histopathological analysis of explanted hearts was heterogeneous; some cases showed fibro-fatty infiltration of the right ventricle, some of the left ventricle, and some had no observable fibro-fatty replacement.52

Final considerations

In view of the foregoing, we conclude that the PCMs, particularly the dilated form (DCM), reflect a complex, highly heterogeneous syndrome of challenging diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. In this scenario, molecular NGS diagnosis can be a very useful tool for clinical cardiologists practice. Although still incipient in Brazil, the use of genetic testing in DCM and HTx services should be considered, since etiological diagnosis often allows a more assertive clinical management and risk stratification. Moreover, clinical and genetic screening of patients' relatives with these conditions is somewhat neglected, although it is a recommended approach. In this way, cardiomyopathy units and HTx services, as well as correlated research groups, should address this topic more incisively and focus on disseminating knowledge among health professionals and in the society as a whole.

Despite its potential benefits, the limitations of genetic testing should not be overlooked. The possible psychological impact of the genetic testing results on patients and their families should be anticipated and discussed. In addition, genetic testing cannot determine whether the proband will develop symptoms, as well as the severity of these potential symptoms.53

Finally, we illustrate the present article with a clinical case from our practice in which genetic testing was part of the clinical evaluation.

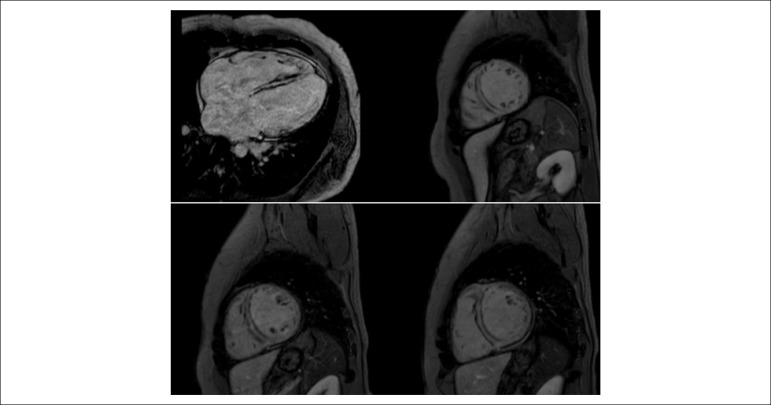

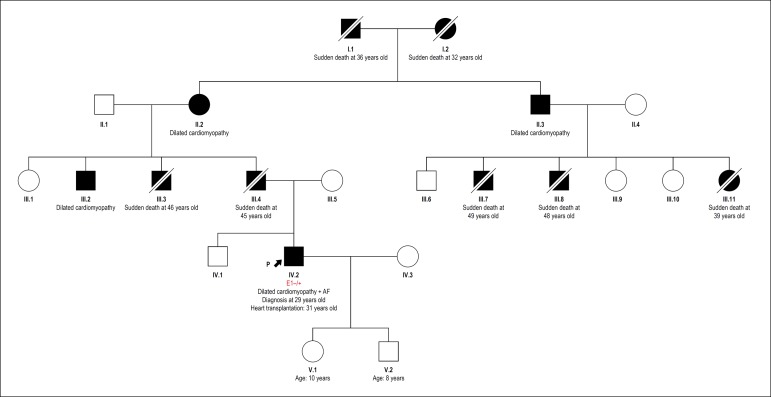

Clinical case: A 30-year-old male was hospitalized due to congestive HF (NYHA functional class III). After 1 year of occasional palpitations, a diagnosis of DCM was established. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, which revealed diffuse hypokinesis, left ventricular dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction, 46%), and diffuse mesoepicardial fibrosis (Figure 1). Comparison with a previous echocardiogram performed two years latter suggested a rapid clinical progression (left ventricular ejection fraction, 32%); systolic and diastolic diameters, 49 and 58 mm, respectively; left atrial diameter, 44 mm. Echocardiogram showed atrial fibrillation and the coronary angiography did not reveal any evidence of coronary heart disease. Taking into consideration, the severity of the case and a positive family history of sudden death (Figure 2), genetic testing was performed (NGS panel for DCM). A LMNA p.Leu176Pro variant was identified, providing etiological confirmation for familial DCM. Based on these findings an ICD was implanted for primary prevention, despite of the left ventricular ejection fraction > 30%. Consistent with descriptions in the literature, cardiolaminopathy of the patient did not respond adequately to optimized clinical treatment and progressed rapidly to HTx. One year later, the patient developed anasarca and was hospitalized again, requiring positive inotropic supporting with intravenous agents. HTx was performed 2 months later. The patient’s children (both under 10 years of age) were apparently healthy. As the mean age of diagnosis of LMNA gene carriers is from the third decade of life onward, ethical recommendations for genetic testing in underage relatives were followed, respecting the appropriate age for genetic counseling.54 However, it is important to mention that cases of children affected by LMNA cardiomyopathy have been reported rarely, which should call into question the current expectant management of young children of patients with cardiolaminopathies.55

Figure 1.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing extensive and diffuse area of mesocardial fibrosis.

Figure 2.

Index case heredogram showing involvement in first, second and third degree relatives. AF: atrial fibrillation.

Footnotes

Sources of Funding

There were no external funding sources for this study.

Study Association

This article is part of the thesis of master submitted by Filipe Ferrari, from Graduate Program in Cardiology and Cardiovascular Sciences, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: Lamounier Júnior A, Stein R; Acquisition of data and Analysis and interpretation of the data: Lamounier Júnior A, Ferrari F, Stein R; Obtaining financing: Stein R; Writing of the manuscript and Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Lamounier Júnior A, Ferrari F, Max R, Ritt LEF, Stein R.

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Weber R, Kantor P, Chitayat D, Friedberg MK, Golding F, Mertens L, et al. Spectrum and outcome of primary cardiomyopathies diagnosed during fetal life. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(4):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinto YM, Elliott PM, Arbustini E, Adler Y, Anastasakis A, Böhm M, et al. Proposal for a revised definition of dilated cardiomyopathy, hypokinetic non-dilated cardiomyopathy, and its implications for clinical practice: a position statement of the ESC working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2016 Jun 14;37(23):1850–1858. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakalakos A, Ritsatos K, Anastasakis A. Current perspectives on the diagnosis and management of dilated cardiomyopathy Beyond heart failure: a Cardiomyopathy Clinic Doctor’s point of view. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2018 May 25; doi: 10.1016/j.hjc.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10(9):531–547. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dadson K, Hauck L, Billia F. Molecular mechanisms in cardiomyopathy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131(13):1375–1392. doi: 10.1042/CS20160170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merlo M, Cannatà A, Gobbo M, Stolfo D, Elliott PM, Sinagra G. Evolving concepts in dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(2):228–239. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hershberger RE, Cowan J, Morales A, Siegfried JD. Progress with genetic cardiomyopathies: screening, counseling, and testing in dilated, hypertrophic, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(3):253–261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.817346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teekakirikul P, Kelly MA, Rehm HL, Lakdawala NK, Funke BH. Inherited cardiomyopathies: molecular genetics and clinical genetic testing in the postgenomic era. J Mol Diagn. 2013 Mar;15(2):158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershberger RE, Givertz MM, Ho CY, Judge DP, Kantor PF, McBride KL, et al. Genetic Evaluation of Cardiomyopathy-A Heart Failure Society of America Practice Guideline. J Card Fail. 2018 Mar;24(5):281–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charron P, Arad M, Arbustini E, Basso C, Bilinska Z, Elliott P, et al. European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases Genetic counseling and testing in cardiomyopathies: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(22):2715–2726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herman DS, Lam L, Taylor MR, Wang L, Teekakirikul P, Christodoulou D, et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):619–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuenca S, Ruiz-Cano MJ, Gimeno-Blanes JR, Jurado A, Salas C, Gomez-Diaz I, et al. Inherited Cardiac Diseases Program of the Spanish Cardiovascular Research Network (Red Investigación Cardiovascular). Genetic basis of familial dilated cardiomyopathy patients undergoing heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35(5):625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang SB, Liu YX, Fan LL, Huang H, Li JJ, Jin JY, Xiang R. A novel heterozygous variant p.(Trp538Arg) of SYNM is identified by whole-exome sequencing in a Chinese family with dilated cardiomyopathy. Ann Hum Genet. 2019;83(2):95–99. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu YJ, Wang ZS, Yang CX, Di RM, Qiao Q, Li XM, Gu JN, et al. Identification and Functional Characterization of an ISL1 Mutation Predisposing to Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2018 Dec 10;13(2) doi: 10.1007/s12265-018-9851-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forleo C, D’Erchia AM, Sorrentino S, Manzari C, Chiara M, Iacoviello M, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing detects novel gene-phenotype associations and expands the mutational spectrum in cardiomyopathies. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minoche AE, Horvat C, Johnson R, Gayevskiy V, Morton SU, Drew AP, et al. Genome sequencing as a first-line genetic test in familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Genet Med. 2019;21(3):650–662. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0084-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park HY. Hereditary Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Recent Advances in Genetic Diagnostics. Korean Circ J. 2017;47(3):291–298. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2016.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein R, Trujillo JP, Silveira AD, Júnior AL, Iglesias LM. Avaliação Genética, Estudo Familiar e Exercício. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2017 doi: 10.5935/abc.20170015. [online] ahead print, PP.0-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S, Baldinger SH, Gandjbakhch E, Maury P, Sellal JM, Androulakis AF, et al. Long-term arrhythmic and non arrhythmic outcomes of lamin A/C mutation carriers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(21):2299–2307. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortiz-Genga MF, Cuenca S, Dal Ferro M, Zorio E, Salgado-Aranda R, Climent V, et al. Truncating FLNC Mutations Are Associated With High-Risk Dilated and Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(22):2440–2451. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domínguez F, Cuenca S, Bilińska Z, Toro R, Villard E, Barriales-Villa R, et al. European Genetic Cardiomyopathies Initiative Investigators Dilated Cardiomyopathy Due to BLC2-AssociatedAthanogene 3 (BAG3) Mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(20):2471–2481. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tayal U, Prasad S, Cook SA. Genetics and genomics of dilated cardiomyopathy and systolic heart failure. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):20–20. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0410-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNally EM, Mestroni L. Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Genetic Determinants and Mechanisms. Circ Res. 2017;121(7):731–748. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JS, Cook SA. Role of titin in cardiomyopathy: from DNA variants to patient stratification. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15(4):241–252. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peña-Peña ML, Monserrat L. Papel de la genética en la estratificación del riesgo de pacientes con miocardiopatía dilatada no isquémica. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72(4):277–362. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seidelmann SB, Laur O, Hwa J, Depasquale E, Bellumkonda L, Sugeng L, et al. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy diagnosis is commonly overlooked at the time of transplant listing. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35(4):474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franaszczyk M, Chmielewski P, Truszkowska G, Stawinski P, Michalak E, Rydzanicz M, et al. Titin Truncating Variants in Dilated Cardiomyopathy - Prevalence and Genotype-Phenotype Correlations. PLoSOne. 2017;12(1):e0169007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts AM, Ware JS, Herman DS, Schafer S, Baksi J, Bick AG, et al. Integrated allelic, transcriptional, and phenomic dissection of the cardiac effects of titin truncations in health and disease. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(270):270ra6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cicerchia MN, Pena Pena ML, Salazar Mendiguchia J, Ochoa J, Lamounier Jr A, Trujillo JP. Prognostic implications of pathogenic truncating variants in the TTN gene. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(Suppl 1):875–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tayal U, Newsome S, Buchan R, Whiffin N, Walsh R, Barton PJ, et al. Truncating variants in titin independently predicts early arrhythmias in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(19):2466–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware JS, Li J, Mazaika E, Yasso CM, DeSouza T, Cappola TP, et al. Shared Genetic Predisposition in Peripartum and Dilated Cardiomyopathies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(3):233–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linschoten M, Teske AJ, Baas AF, Vink A, Dooijes D, Baars HF, et al. Truncating Titin (TTN) Variants in Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail. 2017;23(6):476–479. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware JS, Amor-Salamanca A, Tayal U, Govind R, Serrano I, Salazar-Mendiguchía J, et al. Genetic Etiology for Alcohol-Induced Cardiac Toxicity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(20):2293–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Captur G, Arbustini E, Bonne G, Syrris P, Mills K, Wahbi K, et al. Lamin and the heart. Heart. 2018;104(6):468–479. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peretto G, Sala S, Benedetti S, Di Resta C, Gigli L, Ferrari M, Della Bella P. Updated clinical overview on cardiac laminopathies: an electrical and mechanical disease. Nucleus. 2018;9(1):380–391. doi: 10.1080/19491034.2018.1489195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ito M, Nomura S. Cardiomyopathy with LMNA Mutation. International Int Heart J. 2018;59(3):462–464. doi: 10.1536/ihj.18-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasselberg NE, Haland TF, Saberniak J, Brekke PH, Berge KE, Leren TP, et al. Lamin A/C cardiomyopathy: young onset, high penetrance, and frequent need for heart transplantation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(10):853–860. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC) Eur Heart J. 2015;36(41):2793–2867. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charron P, Arbustini E, Bonne G. What Should the Cardiologist know about Lamin Disease? Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2012;1(1):22–28. doi: 10.15420/aer.2012.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Captur G, Arbustini E, Syrris P, Radenkovic D, O’Brien B, Mckenna WJ, et al. Lamin mutation location predicts cardiac phenotype severity: combined analysis of the published literature. Open Heart. 2018;5(2):e000915. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kayvanpour E, Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Amr A, Lai A, Haas J, Holzer DB, et al. Genotype-phenotype associations in dilated cardiomyopathy: meta-analysis on more than 8000 individuals. Clin Res Cardiol. 2017;106(2):127–139. doi: 10.1007/s00392-016-1033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Begay RL, Graw SL, Sinagra G, Asimaki A, Rowland TJ, Slavov DB, et al. Filamin C Truncation Mutations Are Associated With Arrhythmogenic Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Changes in the Cell-Cell Adhesion Structures. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4(4):504–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norton N, Li D, Rieder MJ, Siegfried JD, Rampersaud E, Züchner S, et al. Genome-wide studies of copy number variation and exome sequencing identify rare variants in BAG3 as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(3):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reinstein E, Gutierrez-Fernandez A, Tzur S, Bormans C, Marcu S, Tayeb-Fligelman E, et al. Congenital dilated cardiomyopathy caused by biallelic mutations in Filamin C. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(12):1792–1796. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chami N, Tadros R, Lemarbre F, Lo KS, Beaudoin M, Robb L, et al. Non sense mutations in BAG3 are associated with early-onset dilated cardiomyopathy in French Canadians. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(12):1655–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toro R, Pérez-Serra A, Campuzano O, Moncayo-Arlandi J, Allegue C, Iglesias A, et al. Familial Dilated Cardiomyopathy Caused by a Novel Frameshift in the BAG3 Gene. PLoSOne. 2016;11(7):e0158730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rafiq MA, Chaudhry A, Care M, Spears DA, Morel CF, Hamilton RM. Whole exome sequencing identified 1 base pair novel deletion in BCL2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3) gene associated with severe dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) requiring heart transplant in multiple family members. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(3):699–705. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hermida-Prieto M, Monserrat L, Castro-Beiras A, Laredo R, Soler R, Peteiro J, et al. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy and isolated left ventricular non compaction associated with lamin A/C gene mutations. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(1):50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Haas J, Zhu F, Geier C, Kayvanpour E, Liss M, et al. Clinical genetics and outcome of left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(46):3449–3460. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.López-Ayala JM, Gómez-Milanés I, Sánchez Muñoz JJ, Ruiz-Espejo F, Ortíz M, González-Carrillo J, et al. Desmoplakin truncations and arrhythmogenic left ventricular cardiomyopathy: characterizing a phenotype. Europace. 2014;16(12):1838–1846. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Groeneweg JA, van der Zwaag PA, Jongbloed JD, Cox MG, Vreeker A, de Boer RA, et al. Left-dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy in a large family: associated desmosomal or non desmosomal genotype? Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(4):548–559. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcia-Pavia P, Syrris P, Salas C, Evans A, Mirelis JG, Cobo-Marcos M, et al. Desmosomal protein gene mutations in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy undergoing cardiac transplantation: a clinic pathological study. Heart. 2011;97(21):1744–1752. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2011.227967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burkett EL, Hershberger RE. Clinical and genetic issues in familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(7):969–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Girolami F, Frisso G, Benelli M, Crotti L, Iascone M, Mango R, et al. Contemporary genetic testing in inherited cardiac disease:tools, ethical issues, and clinical applications. T cardiovasc Med(Hagerstown) 2018;19(1):1–11. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Berlo JH de Voogt WG, van der Kooi AJ van Tintelen JP, BonneG Yaou RB, et al. Meta-analysis of clinical characteristics of 299 carriers of LMNA gene mutations: do lamin A/C mutations :portend a high risk of sudden death¿. J Mol Med (Berl) 2005;83(1):79–83. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]