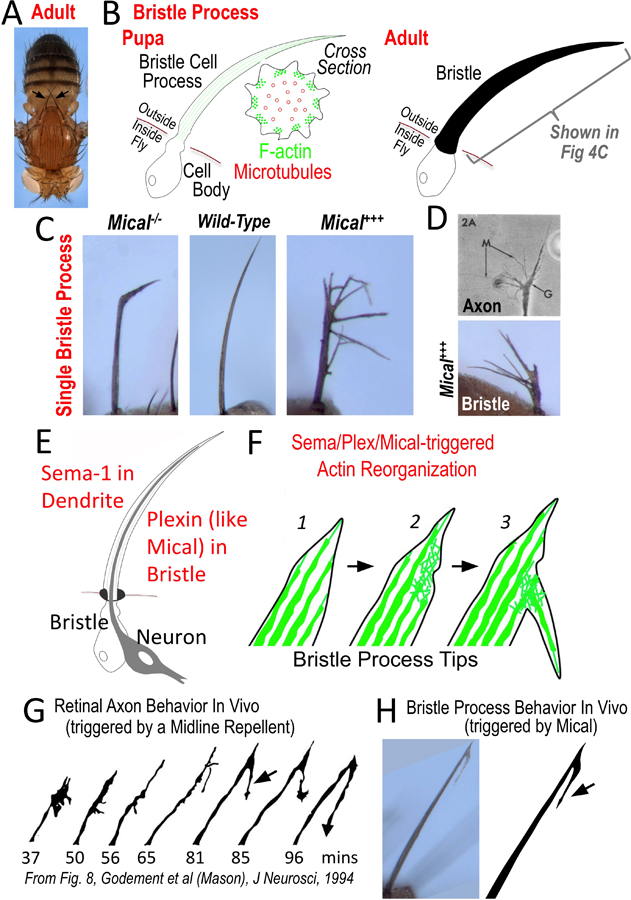

Figure 4. The bristle cell as a simple membranous process-containing cell.

(A–B) The bristle cell with its long process provides a model cellular process. (A) Note the long single cell bristle processes on the body of the adult fly (e.g., each arrow points to a single bristle cell with its process). Images reproduced with permission from [74]. (B, left) The stereotypical arrangement of F-actin and microtubules pushes out the bristle process during pupal development. (B, right) The bristle cell also secretes a chitin cuticle that wraps around its cellular process – preserving a record in the adult of its developmental history and allowing a rapid initial characterization (in different contexts and genetic backgrounds) without requiring tissue processing. (C–D) Changing Mical levels alters bristle process extension and morphology – including (D) inducing it to resemble an axon growth cone. Images reproduced with permission from [74,76,107]. (E–F) Sema (on dendrite) interacts with Plexin (on bristle), to activate Mical within the bristle to induce cellular remodeling and branching (F; [74]). (F) This remodeling and branching occurs through the disassembly of F-actin (green) within bristle processes (2), which then allows currently unknown factors to form this actin-rich branch (3). (G–H) The Sema/Plexin/Mical-induced bristle branching (H, arrow) is remarkably similar to an axon’s response in vivo to a repellent (G, arrow). In particular, the axon’s (growth cone’s) response is to decrease in size (G, compare 37mins to 50 and 56mins) and then form a new “back” branch (G, arrow) [87] – which is the same response seen in the bristle upon Mical activation (H; [74]). Image reproduced with permission from [87].