Abstract

Objectives:

To explores cultural differences between generations of faculty and students in undergraduate medical education and to develop an educational framework for stakeholders involvement.

Methods:

This is a prospective cross-sectional mixed method study. A survey was administered on students and faculty members to measure generational differences using Hofstede’s dimensions of cultural orientation. The study took place at King Abdulaziz University-Faculty of Medicine, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on February 2015. Quantitative methods, descriptive statistics, and correlations and regression analyses were used in data analysis. In addition, qualitative data from focus groups were used to explain findings obtained from the survey.

Results:

A total of 736 respondents were surveyed (129 faculty members and 607 medical students). Faculty members across all generations shared the same cultural values of low power distance and masculinity and high uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation and collectivism. Advanced medical students showed higher power distance, collectivism, masculinity and long-term orientation than faculty members; junior medical students have higher masculinity and lower uncertainty avoidance and collectivism.

Conclusion:

This study explains both the cultural gap between Saudi and Western medical students as well as between Saudi generations, demonstrating the need for customized curricular revisions.

Shortage of physicians is a global issue specially with the increase in life expectancy and population.1,2 In Saudi Arabia, the population almost doubled while the percentage of Saudi to non-Saudi qualified physicians increased from 21.7% to 26% within the last 4 years.3,4 As a result, medical schools in the Gulf Region have been prompted to maximize the number of enrolled students, thereby creating a major challenge for curricular designers and faculty members to achieve the required learning outcomes. Consequently, medical schools in the Gulf Region developed affiliations with international institutions to receive educational guidance and support.5 However, the curricular structure and educational systems from Western and other international institutions are often based on their own educational experience with their students, and therefore, they may not necessarily ensure an educationally effective approach for culturally different learners in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Region, more broadly. Prior studies have shown that cultural differences may impact the educational experience of learners.6 Moreover, cultural differences also change over time. Evidence for studies on cultural differences dates back to Hofstede, who reported unique Saudi cultural orientation. In Hofstede’s cultural framework, there are 5 cultural dimensions: 1) power distance, 2) uncertainty avoidance, 3) masculinity/femininity, 4) individualism/collectivism, and 5) long-term orientation/short-term orientation.6 Hofstede’s reported high levels of power distance, collectivism, uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation among Saudi professional workforce. Later, other reports were published using the same Hofstede scale, but reported inconsistent results.7-9 The discrepancy can be related to several confounders including the era of the study which determines the generation of the sample population with their known differences in cultural orientation.10-21 Generational differences can inform our understanding of learning tendencies and preferences that can impact the structure of medical education.22 For example, Saudi traditionalists (born between the year 1924 and 1945) tend to respect authority (high power distance) while Saudi baby boomers (born between the year 1946 and 1964) who grew up in the era of severe economic deficit from unstudied government spending at that time, therefore they are the generation challenges authorities (low power distance The relationship between both cultural orientation and generations have been demonstrated in previous reports.23-28 As such, these studies have prompted findings on cultural differences and values with Western and Saudi workforce; and moreover, they also noted differences in cultural values through generations. These cultural and generational differences can have significant impact on the learning and best approaches to deliver an effective educational system. Moreover, these findings can advance our understanding of generational gaps beyond Hofstede and also modify the Western conceptualization of today’s students driven by learner achievement, affiliation and power differences.29,30

This study examines cultural differences between generations in Saudi Arabia, specifically aimed at 4 generations: i) baby boomers, represented by faculty members born between the year 1046 and 1064; ii) generation X, represented by faculty members born between the year 1965 and 1980; iii) generation Y, represented by junior faculty members and advanced medical students born between the year 1981 and 1995; and iv) generation Z, represented by early years medical students born between 1996 and 2010. We use qualitative and quantitative findings from cultural differences surveyed from faculty and learners across generations to develop an educational framework and strategies targeting medical education in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Region.

Methods

After obtaining the institutional ethical approval, a cross-sectional explanatory mixed methods approach was used to identify the cultural orientation of the 4 generations participating in medical education including faculty members and undergraduate medical students. Structured survey questionnaire was administered to all faculty members and undergraduate medical students at King Abdulaziz University-Faculty of Medicine (KAU-FOM), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. There were no exclusion criteria. The second step involved 2 focus groups from Generation Z medical students. The study was conducted in February 2015.

Quantitative study. Selection of survey questionnaire

CVSCALE. Despite extensive use of the Hofstede framework, several studies confirmed lack of validity evidence, including reliability and both convergent and discriminant validity.19-21,23-25 As such, we adopted the “CVSCALE” developed by Yoo et al in this study, which includes published validity evidence in several reports.27,28,31,32 The CVSCALE is a 5-dimensional Likert scale including 26-item that measures power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity, collectivism, and long-term orientation.27 All items are phrased as expressions on how the respondents perceive situations that demonstrate each cultural dimension. The scale includes 5 items for the power distance, 5 items for uncertainty avoidance, 6 items for collectivism, 4 items for masculinity and 6 items for long-term orientation. Arabic translation was used; to ensure exact meaning, the authors verified the translation through retranslation of the scale. Translation was included in the survey before distribution in order to ensure full understanding of the items by participants (Appendix 1).

Participants

The target population was all faculty members and medical students studying at KAU-FOM. Survey questionnaires were distributed on May 2015 to all Saudi faculty members and to all students enrolled. Only completed forms were used for the study.

Data analysis

All data were entered and analyzed by using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL.). Participants were grouped into generations based on their birth date. Descriptive statistics were used to examine means for each cultural dimension and generation. Cronbach’s alpha for all the items was also estimated to determine the internal-consistency reliability of the CVSCALE, contributing to internal structure validity evidence. Pairwise correlations were calculated to evaluate the presence and extent of association between different cultural dimensions within each generation. Correlations and multiple linear regression analyses were used to understand the bivariate and multivariate relationships.

Qualitative study (focus groups). Participants

Medical students were recruited to participate in focus groups. Since all undergraduate medical students belonged to Generation Z, only Generation Z students were included in the focus group study. Two focus groups were conducted in separate days consisting of 7 medical students from both genders. Students were divided by gender, as there are known differences by gender. The same interviewer and observer conducted both sessions when the interviewer asked the questions and ran the discussions whereas the observer recorded the candidates’ responses in writing. No video or audio recording was used to encourage students to express their true opinions regarding the discussed topics.

Structured questions

A list of structured questions was prepared based on the results obtained from the data analysis of the quantitative section of the study. Five to eight questions were created on each cultural dimension and discussed with both groups (Appendix 2).

Arabic language was used during the discussion to facilitate communication and ensure understanding of the questions. An interviewer and an observer attended both sessions where the interviewer ran the discussion and the observer documented in writing the answers given by the students.

Data analysis

Content analyses following thematic approach with measurement of the level of agreement on the statements from each group. The analysis was conducted by 2 reviewers who inductively identified themes reflected in the data by analyzing all comments using the constant comparative analysis method.33,34

Results

Descriptive statistics

Survey participants included 736 respondents (129 faculty members and 607 medical students with a response rate of 67% and 46%, respectively). Cronbach’s alpha ranged between 0.76 and 0.81, indicating good internal consistency reliability. More than half of the females (63%) and males (52.4%) were from generation Y. More than half of the faculty members belonged to Generation Y, 24% were generation X and 17.8% were baby boomers. Almost two-third of the students were Generation Y and the remaining one third were Generation Z. More than half of the faculty and almost two-third of the students were from Generation Y.

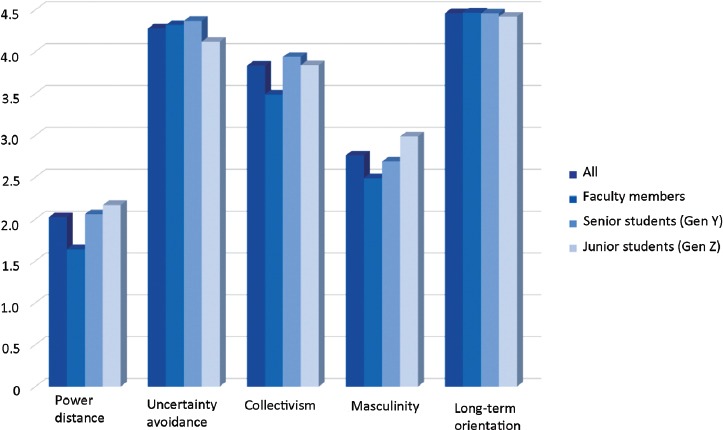

In general, Saudis involved in undergraduate medical education rated high for long-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance cultural dimensions and lesser for collectivism and masculinity and surprisingly, their lowest score was for their power distance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison between mean score values for individual cultural dimensions in Saudi generations involved in medical education.

Examining bivariate relationships. Correlations

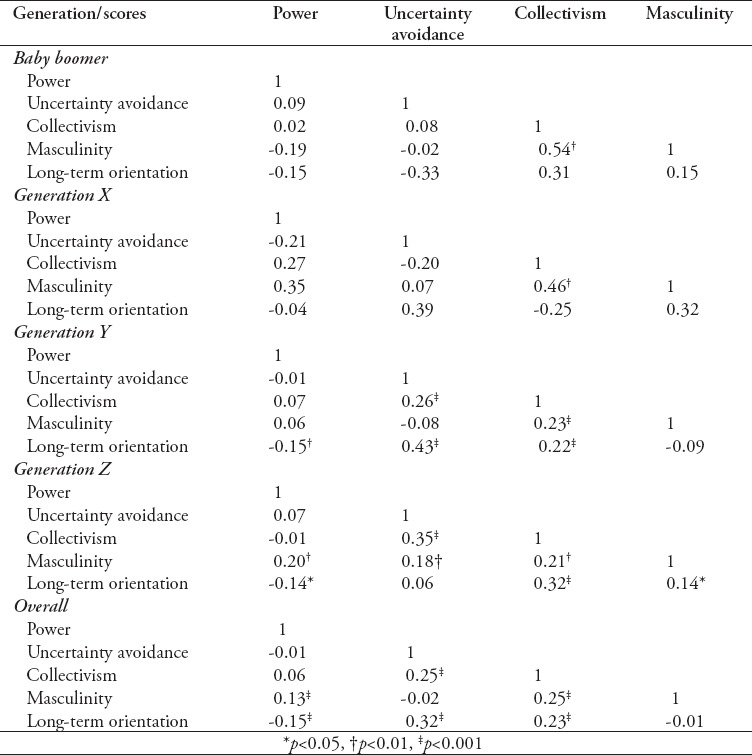

Among different generations, there were statistically significant differences for power distance, uncertainty avoidance and masculinity dimensions. Power distance was found increasing over generations being lowest in baby boomers and highest in Generation Z; the opposite was found for uncertainty avoidance where generation Z scored lowest in this dimension. Masculinity was high in baby boomers reaching the lowest level in generation X then started to increase again reaching its highest level in generation Z. Despite of being in one generation, there was an identified significant difference in scores for all cultural dimensions with the exception of uncertainty avoidance between generation Y faculty members and generation Y students (Figure 1). Pairwise correlations between cultural dimensions within each generation showed strong positive correlation between masculinity and collectivism and a negative association between masculinity and power distance, masculinity and uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation and power distance in baby boomers. Generation X also had strong positive correlations between masculinity and collectivism, but negative correlations between uncertainty avoidance and power distance, collectivism and uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation and power distance and long-term orientation and collectivism. While Generation Y showed a very strong correlation between masculinity and collectivism as well as between collectivism and uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation and collectivism. They also showed a strong negative association between long-term orientation and power distance and a less significant negative association between uncertainty avoidance and power distance, masculinity and uncertainty avoidance, and long-term orientation and masculinity. On the other hand, generation Z had also positive correlation between masculinity and collectivism with a similar significance to baby boomers and generation X which lesser than generation Y. They also showed a very strong positive association between collectivism and uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation and collectivism and to a lesser extent between masculinity and power distance, masculinity and uncertainty avoidance, masculinity and collectivism. They also showed fairly significant positive association between long-term orientation and power distance as well long-term orientation and masculinity. Significant negative association was detected between long-term orientation and power distance and a negative correlation between collectivism and power distance which was not statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inter-scale associations by generation: pairwise correlations.

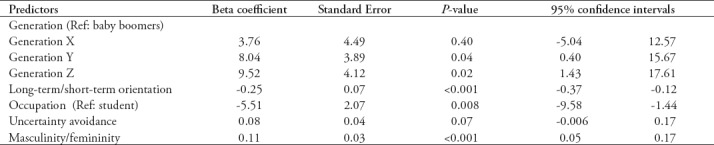

Understanding multivariate relationships. Multiple linear regression

Multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify predictors of power distance. Being from generations Y and Z increased the mean power distance score by 8 and 9.5 on average, respectively, compared to the baby boomer generation, after adjusting for long-term orientation, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity cultural dimensions and occupation. As the generation made all efforts to prepare for the future, their average power distance score decreased by 0.25 points. Being a faculty decreased power distance score by 5.51 points on average, adjusting for type of generation, occupation, long-term orientation, uncertainty avoidance and masculinity cultural dimensions. When the preference is for achievement, heroism assertiveness and material rewards for success the predicted power distance score, which increased by 0.11 on average after controlling for generation, occupation, long-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance cultural dimensions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression model for predictors of the power distance cultural dimension among the studied participants (N=736).

Linear regression analysis for uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculine/feminine and long-term orientation/short-term orientation did not show any statistically significant findings, and as such are not presented.

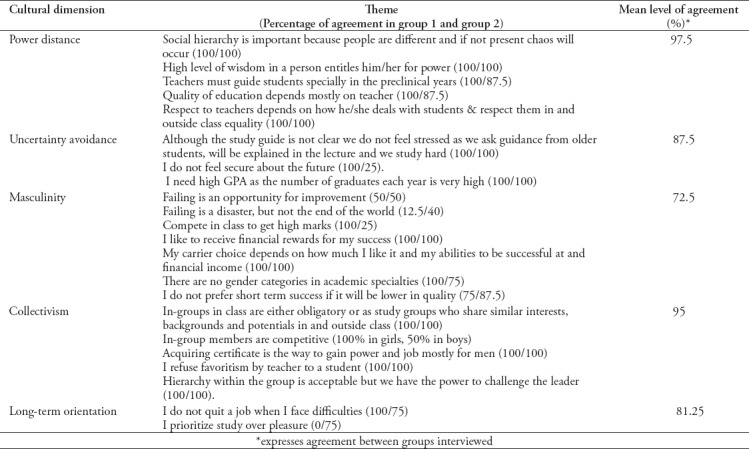

Qualitative results

Content analysis for the results obtained from the focus groups showed that Generation Z medical students at KAU-FOM explained the quantitative results. “Social hierarchy is important because people are different and if not present chaos will occur” Moreover, “high level of wisdom in a person entitles him/her for power”. Participants believed that teachers play an important role in their success “Teachers must guide students especially in the preclinical years” and “Quality of education depends mostly on teacher”. This also explained why Generation Z were not stressed by the lack of clear study guides “Although the study guide is not clear we do not feel stressed as we ask guidance from older students, will be explained in the lecture and we study hard” and why their main focus is obtaining high GPA “I need high GPA as the number of graduates each year is very high” & “I do not feel secure about the future”. The same reason makes them competitive in class “Compete in class to get high marks”. They are materialistic “I like to receive financial rewards for my success” and that can contribute to their carrier choice “My carrier choice depends on how much I like it and my abilities to be successful at and financial income”.

Not all Generation Z students considered failing in exams as disasters “failing is an opportunity for improvement”. They prefer to be within a group “in-groups in class are either obligatory or as study groups who share similar interests, backgrounds and potentials in and outside class” but that did not limit their competitiveness or contradict with their acceptance to hierarchy “in-group members are competitive”, “hierarchy within the group is acceptable but we have the power to challenge the leader”. They consider certification the source of power in life “acquiring certificate is the way to gain power and job mostly for men” and their persistence help them achieve their goals “I do not quit a job when I face difficulties” (Table 3).

Table 3.

Content analysis for focus groups.

Discussion

This study examines cultural differences and the trends across generations based on a sample of faculty and medical students in Saudi Arabia, aimed to develop educational frameworks that can promote learning and improved educational environment. Findings demonstrates the role of cultural orientation in the development of inter-generational as well as intra-generational gaps with an evidence against students’ stereotypes and the effectiveness of replicating educational strategies used in culturally different institutions. The results obtained allowed us to profile the Saudi generations involved in undergraduate medical education. Faculty members (baby boomers, generation X, generation Y).27,35,36 Irrespective of participation of 3 different generations in teaching undergraduate medical education at KAU, all faculty members exhibit similar cultural orientation. On the personal level, they all believe in the interdependence between all social classes, feel entitled to be involved in all administrative decisions, emotional, skeptical and resistant to change out of fear from the unknown. They are modest and care only for themselves and their immediate families. With their focus on the future, they work in order to live, respect tradition, value long term commitments, future oriented, and have a great need for clarity and structure in order to feel secure. In class, Saudi faculty members adopt a student-centered approach where students are responsible for their own path and solving their own problems. They expect students to speak up freely in class, initiate discussions and learn how to learn. Also, they have high respect to tradition, value long-term commitments and they are future oriented.

Advanced years medical students (Generation Y)

Although advanced medical students share the same generation as junior faculty members, they exhibit different cultural orientation. The most likely explanation is the sense of insecurity that was experienced in the country for the very first time in 1990, the year of birth of the Generation Y medical students, with the beginning of the first Gulf War. As a result, their parents had the impulse for isolation and overprotection prohibiting them from outdoor activities where they cannot be supervised and surrounded them with electronics for indoor entertainment.

Therefore, Generation Y medical students accept and expect to be dependent. They expect student-centered education where faculty members must pave their educational path, solve their problems, tell them the solution for everything and teach them how to implement it and they grade the level of education based on the faculty member ability to provide their needs.12,14,27,35,36

Generation Y medical students may not initiate discussions or ask questions in class regardless of how well they know the material, out of fear from consuming time which may prevent the faculty member completing the class content.34 Also, they have a tendency to ask questions individually after class, possibly to avoid disturbing the class harmony or avoid embarrassment and losing face or even to prevent others from benefiting from the answers.33,34 They have the highest need among all other Saudi generations for affiliation to a cohesive in-group sharing a common criteria (ethnic origin, family wealth, religiosity) where the wisest among them is nominated as a leader. They are so keen to build social networks and their resources are pooled for the group benefit. Their obsession with harmony preservation makes them very attached to their groups avoiding any confrontation and rejection.37,38 The relationship between their cohesive groups is self-centered and competitive. Generation Y students do their best to make the group visible. They are very attached to anything big and fast27 favoring engagement in quick projects with big impact regardless of quality of the results. For them, education is the key for social acceptance and having a certification is the proof of illegibility to join the higher status group in the society regardless of the level of acquired competences.26

Early years medical students (Generation Z). Members of this generation exhibit the highest level of masculinity among all Saudi generations. This results in their adhesiveness to male gender role that focuses on values, money, success and competition. They also possess the greatest need for power, assertiveness, dominance, wealth, and material success. Their definition of success is money and that can very well influence their subspecialty career choices. They prioritize economic growth, find beauty in everything that is big and fast, and tend to resolve conflicts by force.38 Although their older peers are loyal and willing to scarify for their in-group, early-years medical students are less adherent within the in-group and their relationship remains as long as it avoids any personal harm. They encourage thrift and make much effort to prepare for the future.

Their level of acceptance of relationship hierarchy is higher than other Saudi generations, which was the root cause for their unique cultural orientation. They expect to be placed in their rightful place in the society and see the acquisition of different luxury brands as an indication of high status.33,39 They believe that social hierarchy is the controlling factor against chaos. In school, they replace parents by teaching faculties who will set their goals and line up their educational path explaining the reason for using the faculty excellence in providing their needs as a benchmark for the effectiveness of learning of a topic.32 It can also explain their relaxed attitude, considering practice more important than principles as well as their low focus on the future and high focus on pursuing happiness. Those findings are not surprising in the “bubble wrapped generations” who were raised by the overprotective “Helicopter parents” supervising and interfering with all aspects of their lives making them accustomed that others will take care, protect, solve problems and correct their mistakes. The higher the acceptance of our students for social inequality the more is their need for achievement and success, demonstrated by the acquisition of jewelries and expensive branded items.35

Generation Z students are the most competitive, assertive, ambitious, and the most among other generations to expect material rewards for success, that is true they are called “Trophy kids”. Needing success and unable to make light of failing, neither consider it as an opportunity to learn. They are more self-centered, have more appeal for heroic actions with a greater tendency to use force in conflict resolution than any other generation. In class, Generation Z medical students prefer large class teaching where they listen to lectures without interruption. Expecting the faculty members to provide all the needed knowledge and guide towards obtaining certification, they are not willing to initiate discussions or ask questions during class avoiding wasting the teaching time and providing the greatest opportunity for the faculty member to complete the class contents.35,39 Therefore, faculty members should ask students several times if they have questions and push them to respond to recall questions in order to initiate an active learning environment. Other reasons that might contribute in their unwillingness to take imitative in class is their high competitiveness making them ask questions individually after class so other students will not benefit from the answers. While results from this study applied to one medical school in a multi-cultural country, we found evidence that can be meaningfully applied to further educational structure in Saudi medical schools. As this is the main limitation of this study, we are planning to conduct additional studies to examine direct comparisons with other regions in the country as well as neighboring countries. Moreover, efforts are underway to further evaluate factors that may play a role in the cultural orientation like gender, ethnicity, and geographical location. Based on these findings, we suggest the following recommendations: i) Lectures and large group teaching must be used as the main methods for teaching during which faculty members must only present standardized information as students will never question or challenge them. ii) Role modelling may be emphasized. iii) Additional support is needed to promote self-directed learning methods to introduce the concept of “learning how to learn” in order to equip students for an independent life-long learning. iv) Provide structured student mentoring, guide and support systems. v) instructional approaches such as small-group learning methods, PBL, learning projects and team-based learning strategies may need to be supplemented with additional mentoring to enhance their effectiveness. vi) Introduce mandatory extracurricular courses such as critical thinking and teamwork.

In class with Generation Y students, faculty members need to: resent precise and clear objectives for the session; explain background knowledge first before presenting applications; encourage discussions through personal invitations; whenever feedback is given it must be in private.

In class with Generation Z students, faculty members need to: encourage students’ interaction through general invitations; include personal experience in the topic material; use students’ high need to be visible.

In conclusion, understanding generational gaps and the cultural context may promote constituting an improved learning environment for students and faculty.

Footnotes

References

- 1.National Health Service. Available from:https://improvement.nhs.uk/uploads/documents/Clinical_workforce_report.pdf .

- 2. [cited 2016 April 5];Association of American Medical Colleges. New Research Confirms Looming Physician Shortage. Available from URL:https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/458074/2016_workforce_projections_04052016.html .

- 3.General Authority for Statistics. Available from:https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/13 .

- 4.Ministry of Health. Statistics. Available from:http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/StatisticalBook-1436.pdf .

- 5.Telmisani A, Zaini R, Ghazi H. Medical education in Saudi Arabia:a review of recent developments and future challenges. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2011;17:703–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofstede G. Cultural differences in teaching and learning. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1986;10:301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alamri A, Cristea A, Al-Zaidi M. Saudi Arabian cultural factors and personalized eLearning. EDULEARN14 Proceedings. 2014:7114–7121. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Twaijri M, Al-Muhaiza I. Hofstede's cultural dimensions in the GCC countries:an empirical investigation. International Journal of Value Based Management. 1996;9:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjerke J, Bakir A, Rose G. A test of validity of Hofstede's cultural framework. Advances in Consumer Research. 2008;35:762–763. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ismail M, Lu H. Cultural dimensions and career goals of the Millennial Generation:An integral conceptual framework. The Journal of International Management Studies. 2014;9:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu H, Miller P. Leadership style:The X generation and baby boomers compared in different cultural contexts. Leadership and Organization Development Journal. 2005;26:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.In Jamali D, IGI Global. Hershey (PA): IGI Global; 2017. Comparative perspectives on global corporate social responsibility. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu L, Kao S. Traditional and Modern Characteristics Across the Generations:Similarities and Discrepancies. J Soc Psychol. 2002;142:45–59. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stern P. Generational differences. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27:187–194. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.32329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrow G, Rothwell C, Burford B, llling J. Cultural dimensions in the transition of overseas medical graduates to the UK workplace. Medical Teacher. 2013;35:e1537–e1545. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.802298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jippes M, Majoor G. Influence of national culture on the adoption of integrated medical curricula. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malone B, Hasan S, Sanni A, Reilly J. Mismatch of Cultural Dimensions in an Urban Medical Educational Environment. Journal of Biomedical Education. 2013;2013:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofstede G. Dimentionalizing Cultures:The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. 2011;2:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofstede GH, editor. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications; 1980. Culture's consequences:International differences in work related values. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wursten H, Jacob C. [cited 2013];The impact of culture on education. “The Hofstede Center. Available from: https://geerthofstede.com/tl_files/images/site/social/Culture%20and%20education.pdf .

- 21.Blodgett J, Bakir A, Rose G. A test of validity of Hofstede's cultural framework. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 1008;25:339–349. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talmon GA, Dallaghan GLB. Omaha (NE): Alliance for Clinical Education; 2017. Mind the gap:generational differences in medical education. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakir A, Blodgett JG, Vitell SJ, Rose GM. A preliminary investigation of the reliability and validity of Hofstede's cross cultural dimensions. In: Spotts H, Meadow H, editors. Proceedings of the 2000 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference. Developments in Marketing Science:Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Cham (SW): Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boldgett J, Jeffery G, Lu L, Rose G. Ethical sensitivity to stakeholders interests:Across-cultural comparison. Journal of Academic Marketing Science. 2001;29:190–202. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Signorini P, Wiesemes R, Murphy R. Development of alternative frameworks for exploring intercultural learning:a critique of Hofstede's cultural difference model. Teaching in Higher Education. 2009 May;:253–264. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sondergaard M. Hofstede's consequences:a study of reviews, citations and replications. Organization Studies. 1994;15:447. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoo B, Donthu N, Lenartowicz T. Measuring Hofstede's five dimensions of cultural values at the individual level:Development and validation of CVSCALE. Journal of International Consumer Marketing. 2011;2011:293–210. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasongsukarn K. Validating the cultural value scale (CVSCALE):a case study of Thailand. ABAC Journal. 2009;29:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Twenge JM. Generational changes and their impact in the classroom:teaching Generation Me. Medical Education. 2009;43:398–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borges NJ, Manuel RS, Elam CL, Jones BJ. Differences in motives between Millennial and Generation X medical students. Medical Education. 2010;44:570–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan W, Yim C, Lam S. Is consumer participation in value creation a double edge sward?Evidence from professional financial survives across cultures. Journal of Marketing. 2010;74:48–64. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soares M, Farhangmehr M, Shoham A. Hofstede's dimensions of culture in international marketing studies. Journal of Bushiness Research. 2007;60:227–284. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charmaz K. Reconstructing theory in grounded theory studies. In: Alasuutari P, Bickman L, Branneneditors J, editors. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London (UK): SAGE; 2006. pp. 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe L, O'Brien B, Rees C. Shedding the cobra effect:problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ. 2017;51:40–50. doi: 10.1111/medu.13124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hui C, Triandis H. Individualism-Collectivism:a study of cross-cultural researchers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1986;17:225. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasuya M. Classroom interaction affected by power distance. [cited 2018];Language Teaching Methodology and Classroom Research and Research methods. Available from URL:http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/ documents/college-artslaw/cels/essays/languageteaching/ languageteachingmethodologymichikokasuya.pdf .

- 37.Gerritsem D, Zimmerman J, Ogan A. Exploring power distance, classroom activity, and the international classroom through personal informatics. AIFD workshop preceding. 2015;1 Available from URL:http://ceur-ws.org/V1432/cats_pap2.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J. Santa Barbara (CA): Greenwood Publishing group; 2001. Asian students' classroom communication patterns in US universities:An empiric perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mooij M, Hofstede G. The Hofstede model. Application of global branding and advertising strategy and research. International Journal of Advertising. 2010;29:85–110. [Google Scholar]