Abstract

Purpose

The balance of neuronal excitation and inhibition is important for proper retinal signaling. A previous report showed that diabetes selectively reduces light-evoked inhibition to the retinal dim light rod pathway, changing this balance. Here, changes in mechanisms of retinal inhibitory synaptic transmission after 6 weeks of diabetes are investigated.

Methods

Diabetes was induced in C57BL/6J mice by three intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (STZ, 75 mg/kg), and confirmed by blood glucose levels more than 200 mg/dL. After 6 weeks, whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of electrically evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents from rod bipolar cells and light-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents from A17-amacrine cells were made in dark-adapted retinal slices.

Results

Diabetes shortened the timecourse of directly activated lateral GABAergic inhibitory amacrine cell inputs to rod bipolar cells. The timing of GABA release onto rod bipolar cells depends on a prolonged amacrine cell calcium signal that is reduced by slow calcium buffering. Therefore, the effects of calcium buffering with EGTA-acetoxymethyl ester (AM) on diabetic GABAergic signaling were tested. EGTA-AM reduced GABAergic signaling in diabetic retinas more strongly, suggesting that diabetic amacrine cells have reduced calcium signals. Additionally, the timing of release from reciprocal inhibitory inputs to diabetic rod bipolar cells was reduced, but the activation of the A17 amacrine cells responsible for this inhibition was not changed.

Conclusions

These results suggest that reduced light-evoked inhibitory input to rod bipolar cells is due to reduced and shortened calcium signals in presynaptic GABAergic amacrine cells. A reduction in calcium signaling may be a common mechanism limiting inhibition in the retina.

Keywords: vision, diabetes, GABA, neurons

Neurons generate appropriate responses to environmental cues rapidly and efficiently by the propagation of electrical signals using synaptic transmission—the regulated release of neurotransmitters from vesicles at the synapse. Ca2+ is a vital component of neurotransmitter release as it is involved in several steps preceding, during, and after release. Ca2+ release from internal stores can augment neurotransmitter release long after the termination of the initial stimulus. Disruptions in neuronal Ca2+ signaling are commonly reported in several neurologic disorders.1 Previous studies have shown dysfunctional Ca2+ signaling in neurons in diabetes,2–6 but the effects on neurotransmitter release remain unclear.

Diabetic retinopathy is a common complication of diabetes and the leading cause of blindness in working-age adults.7 Recent studies showed changes in retinal neurons indicating that diabetic retinopathy is a neurologic disease.8–10 Given that one of the earliest reported symptoms of diabetic retinopathy is reduced night vision,10 changes in the rod pathway that detects dim light are of particular interest. In the rod pathway, light is detected by rod photoreceptors that transmit the signal to rod bipolar cells using glutamate.11 Rod bipolar cells release glutamate onto inhibitory amacrine cells that limit the output of the rod pathway by releasing GABA or glycine onto rod bipolar cell terminals.12 There is accumulating evidence for diabetes-induced neuronal dysfunction in the rod pathway. ERGs from diabetic patients have shown changes in oscillatory potentials, which represent signaling between bipolar and amacrine cells, under scotopic (dim light) conditions when the rod pathway is highly active.13–15 Diabetes also reduces light-evoked inhibition from GABAergic amacrine cells in the rod pathway due to reduced GABA release.16 However, the mechanisms underlying the changes in GABA release are not understood.

Rod bipolar cells receive two distinct types of GABAergic amacrine cell-mediated inhibition—feedback and lateral inhibition. Feedback inhibition comes from A17 amacrine cells that are reciprocally activated by rod bipolar cell glutamate release mainly onto Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors.17 Lateral inhibition comes from other nonreciprocal GABAergic amacrine cells.18,19 Previous studies have shown that GABA release underlying both lateral and feedback inhibition is inherently asynchronous.18,20 This type of prolonged release is dependent on a global increase of intracellular Ca2+ that occurs after initial Ca2+ entry, and mediated by Ca2+–induced Ca2+ release (CICR).17,20–22 In diabetic mice, A17 AMPA receptors (R) have reduced Ca2+ permeability.23 Diabetes also compromises Ca2+ signaling in sensory neurons.24–26

Given these reports of dysfunctional Ca2+ signaling in diabetes, we hypothesized that reduced amacrine cell GABA release in the rod pathway is due to a decrease in Ca2+ availability in early diabetes. However, the full-field light stimulus used in the previous study activated multiple retinal neurons, so changes in many different neurons could contribute to reduced inhibition.19 To determine if this decrease was due to inherent amacrine cell dysfunction, amacrine cell inputs to rod bipolar cells were directly activated using an electrical stimulus in the inner plexiform layer near the amacrine cell-rod bipolar cell synapse.18,20 The streptozotocin (STZ) mouse model of type 1 diabetes was used to induce diabetes as it makes it possible to study the neuronal response of individual neurons and the STZ rodent model shows similar effects of diabetes on neurons to those seen in human diabetic patients.14,27 The analysis focused on inputs onto GABACRs because it is the largest component of rod bipolar cell inhibition28 and determined if diabetes is directly changing the timing and Ca2+ sensitivity of amacrine cell release.

Methods

Animals

Animal protocols were approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the guidelines of the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. C57BL/6J male mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) 11 weeks of age were used for all experiments. Animals were housed in the University of Arizona animal facility and given the National Institutes of Health-31 rodent diet food and water ad libitum.

Induction of Diabetes

Five-week-old male mice were fasted 4 hours and then injected intraperitoneally with either streptozotocin (STZ, 75 mg/kg body weight) dissolved in 0.01 M pH 4.5 citrate buffer or citrate buffer vehicle for 3 consecutive days.16,29 Cages were assigned randomly to STZ or control. Body weight and urine glucose were monitored weekly using urine glucose test strips. Six weeks postinjections, mice were fasted 4 hours and blood glucose was measured using the OneTouch UltraMini blood glucose monitoring system (OneTouch UltraMini, LifeScan; Milpitas, CA, USA). STZ-injected animals with blood glucose 200 mg/dL or less were eliminated from the study.

Retinal Slice Preparation

Retinal slices were prepared 6 weeks after injections. For experiments measuring reciprocal feedback inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) and light-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs), retinal slices were prepared from mice dark-adapted overnight and infrared illumination was used during dissections to preserve the light sensitivity.16,30 For experiments recording electrically stimulated rod bipolar cell inhibitory currents, retinal slices were prepared under light-adapted conditions. Briefly, eyes were enucleated from mice killed using carbon dioxide, corneas and lenses removed, eyecups incubated in extracellular solution with hyaluronidase (800 units/mL) for 20 minutes, and retinas removed. The retina was trimmed, mounted onto filter paper, and sliced into 250-μm slices.

Solutions and Drugs

Extracellular solution used as a control bath for dissection and whole cell recordings was bubbled with a mixture of 95%/5% O2/CO2 and contained (in mM) the following: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 20 glucose, 26 NaHCO3, and 2 CaCl2. The intracellular solution used for measuring reciprocal feedback inhibitory currents contained (in mM) the following: 120 CsGluc, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.1 EGTA, 10 TEA-Cl, 10 phosphocreatine-Na2, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Na-GTP, and 50 μM Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and was adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH. The intracellular solution in the recording pipette used for measuring rod bipolar cell electrically evoked (e)IPSCs and light-evoked A17 amacrine cell EPSCs contained (in mM) the following: 120 CsOH, 120 gluconic acid, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 10 TEA-Cl, 10 phosphocreatine-Na2, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Na-GTP, and 50 μM Alexa Fluor 488 and was adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH.

Antagonists were used to isolate receptor input. SR95531 (20 μM) was used to block GABAARs, TPMPA ([1,2,5,6-Tetrahydropyridin-4-yl]methylphosphinic acid hydrate; 50 μM) was used to block GABACRs and strychnine was used to block glycineRs (500 nM when isolating GABAARs and 1 μM when isolating GABACRs). EGTA-acetoxymethyl ester (AM; 50 μM; Invitrogen) was used to increase intracellular Ca2+ buffering. After recording baseline eIPSCs, EGTA-AM was applied to the bath for 5 minutes prior to recording and was present throughout the duration of recording. All antagonists were applied to the slice by a gravity-driven superfusion system (Cell Microcontrols, Norfolk, VA, USA) at a rate of approximately 1 mL/min. Chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise indicated.

Whole-Cell Recordings

Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings from rod bipolar and amacrine cells were made as previously described.16,18 Retinal slices on glass cover slips were placed in a custom chamber and heated to 32°C by temperature controlled thin stage and inline heaters (Cell Microcontrols). For rod bipolar cell reciprocal feedback (f)IPSCs and A17 amacrine cell light-evoked (l)EPSCs, whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were made from dark-adapted retinal slices under infrared illumination at 32°C.18,30 Electrically evoked rod bipolar cell inhibitory currents were recorded under light-adapted conditions at 32°C.

eIPSCs were recorded from rod bipolar cells clamped at 0 mV, the reversal potential for currents mediated by nonselective cation channels. Rod bipolar cell axon terminals were identified morphologically by visualizing Alexa fluorescence using an Intensilight fluorescence lamp and Digitalsight camera controlled by Elements software (Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan).18 Rod bipolar cell eIPSCs were elicited by delivering a 1-ms, 4- to 20-μA stimulus every 60 seconds through a stimulating pipette placed near rod bipolar cell axon terminals by an S48 stimulator (Grass, Warwick, RI, USA) with attached PSIU6 photoelectric isolation unit (Grass). Rod bipolar cell reciprocal feedback inhibitory postsynaptic currents (fIPSC) were elicited every 60 seconds by a 250-ms step depolarization from a holding potential of −60 mV to 0 mV. Light-evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (L-EPSCs) were recorded from A17 amacrine cells clamped at −60 mV, the reversal potential for Cl− channels.

For all recordings, borosilicate glass electrodes (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) had resistances of 5 to 7 MΩ and the series resistance during recordings was typically 10 to 20 MΩ. Liquid junction potentials of 20 mV were corrected prior to recording. Responses were filtered at 5 kHz using a four-pole low-pass Bessel filter on an Axopatch 200 B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The response was digitized at 10 kHz using a Digidata 1440A data acquisition system (Molecular Devices) and Clampex software (Molecular Devices). Alexa fluorescence was imaged at the end of each recording to confirm rod bipolar cell31 and A17 amacrine cell30,32 morphology.

Light Stimulation

Full-field light stimuli were generated by a light-emitting diode (LED, λpeak = 523 nm) projected through the microscope camera port onto the retina. The light stimuli used were calibrated (photons/μm2/s) and converted to rhodopsin isomerizations per second using a collecting area of 0.5 μm.33 Light intensity and duration (30 ms) were controlled by varying the current through the LED.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Traces of IPSCs/EPSCs for each condition were averaged using Clampfit (Molecular Devices). The peak amplitude, charge transfer (Q), and decay to 37% of the peak (D37) were determined. Q was measured over the time of the response, using the same parameters for each condition in the same cell. The timecourse and amount of transmitter release–mediating evoked and reciprocal IPSCs were calculated with custom written Matlab software (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Release functions were calculated by convolution analysis16,18,34 using the relationship:

|

such that

|

where sIPSC(t) is the average spontaneous GABACR or GABAAR-mediated IPSC recorded from rod bipolar cells under adapted conditions16 and F and F−1 represent the Fourier transform and inverse Fourier transform of the function, respectively. Data were down sampled from 10 to 1 KHz and smoothed using a moving average filter (20 points). The software calculated vesicle release from current-time curves by performing deconvolution of the average rod bipolar cell GABAAR or GABACR-mediated current evoked by a single vesicle release (sIPSC[t]).16,18,28 The deconvolution was performed by dividing the fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the single-vesicle release into the FFT of the evoked response (e/fIPSC[t]) and again smoothed similar to the initial current trace. The resulting release traces were analyzed in Clampfit to determine the number of vesicles released (area under the curve) and the D37. The first 100 ms after the initial stimulus that included the peak was used for the early phase of release. The late phase was release from 100 ms until the response returned to baseline.18

For the rod bipolar cell fIPSC and eIPSC experiments, unpaired Student's t-tests (abbreviated as t-test throughout) were used to compare values across two groups of cells. For eIPSCs, data were normalized to GABACR-mediated input per cell. For L-EPSCs, the log of the data were compared with two-way repeated measures ANOVAs to compare values between conditions across light intensities. Pairwise comparisons at each intensity were made using the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) post hoc test. Reported P values reflect the main treatment effect of STZ unless otherwise indicated. Differences were considered significant when P ≤ 0.05. All data are reported as mean ± SEM.

Results

Diabetic Mice Blood Glucose and Body Weight

The fasting blood glucose was significantly higher in STZ treated mice (409 ± 27 mg/dL, n = 12 mice than in control mice (142 ± 9 mg/dL, n = 12 mice; P < 0.0001 t-test). The body weights of diabetic and control mice were 20.6 ± 0.3 and 24.2 ± 0.4 g (P < 0.0001 t-test), respectively.

Early Diabetes Shortens Release Timecourse From GABAergic Amacrine Cells

eIPSCs were recorded from rod bipolar cells. We previously found18,20 that the eIPSCs reflect input from GABAergic amacrine cells that form nonreciprocal lateral inhibitory connections with rod bipolar cells, because they are insensitive to blocking AMPA receptors that are required for bipolar cell glutamate release to activate amacrine cells20 and are blocked by tetrodotoxin,20 which would not affect reciprocal A17 amacrine cells that do not have action potentials.32,35–37 GABACR eIPSCs from control cells had a prolonged response that lasted much longer than the 1-ms stimulus (Table 1; Fig. 1A).18,20 However, GABACR eIPSCs were less prolonged in rod bipolar cells from 6-week diabetic mice. The D37 for GABACR eIPSCs measured in diabetic cells was briefer than that measured in control cells (Table 1; Fig. 1B; P = 0.0006 t-test). In diabetic cells, the charge transfer (Fig. 1C) was on average reduced, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.07). The peak amplitude (P = 1.0) was similar between control and diabetic cells. Deconvolution analysis (Equations 1, 2) was used to estimate the timecourse of GABA release that underlies the eIPSCs16,20,28,34 (Fig. 1D). The prolonged timecourse of GABACR eIPSCs in control cells was due to prolonged GABA release18,20 (Fig. 1E). In diabetic cells, the timecourse of GABA release onto GABACRs was reduced (P = 0.008) but there was no difference in the total amount of vesicle release (P = 0.8, Fig. 1F).

Table 1.

GABAC Receptor (R) eIPSC Values Recorded From Control and Diabetic Rod Bipolar Cells

|

eIPSC |

Q (pA*ms) |

D37 (ms) |

Peak (amp) |

n

(Cells) |

Mice |

| Control GABACR | 24855 ± 6873 | 2088 ± 338 | 13.5 ± 2.1 | 7 | 4 |

| Diabetic GABACR | 10753 ± 3733 | 617 ± 160* | 13.7 ± 3.2 | 10 | 4 |

Data are average values of charge transfer (Q), D37, and peak amplitude.

P < 0.001 when compared with control GABACR values (t-test).

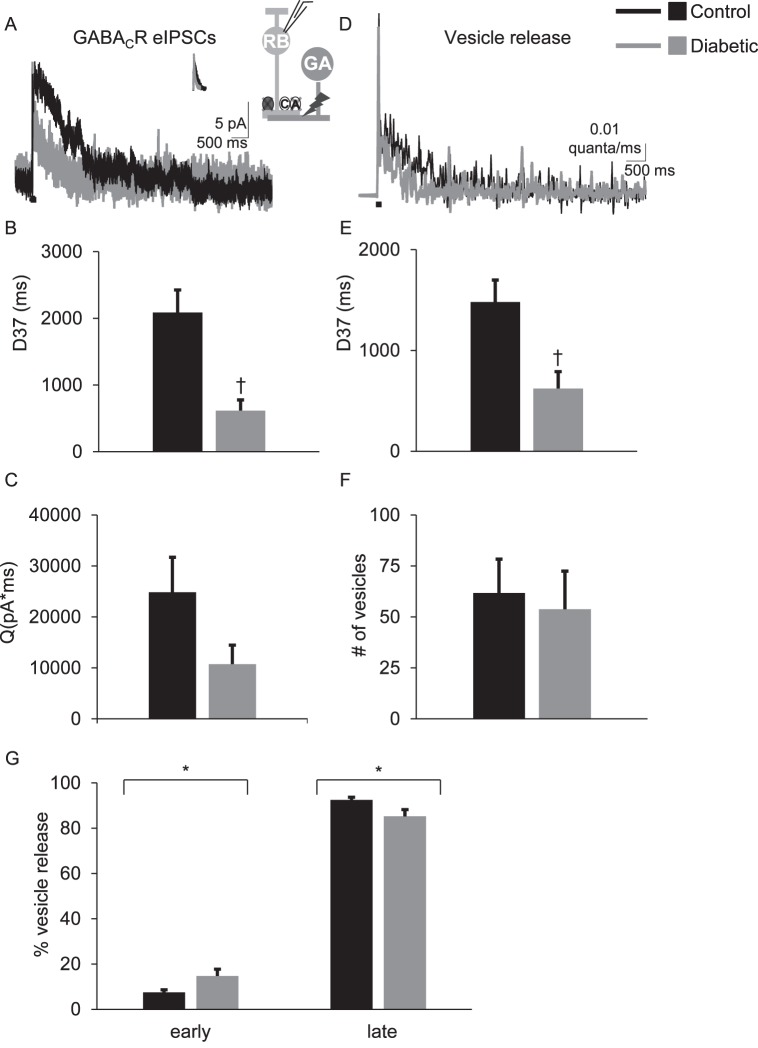

Figure 1.

The timing of electrically evoked GABA release onto rod bipolar cell GABACRs is shortened after 6 weeks of diabetes. (A) Representative traces of rod bipolar cell GABACR eIPSCs evoked by a 1-ms electrical stimulus (black bar, timing not to scale) are shown. The insets show the average sIPSCs used for deconvolution analysis and a GABAergic amacrine cell (GA) being electrically stimulated to release GABA onto GABACRs (C) and GABAARs (A) on a recorded rod bipolar cell. Glycine (dark gray circle) and GABAARs are pharmacologically blocked (X's) to isolate GABACR currents. (B) The D37 was significantly faster in diabetic rod bipolar cells (n = 10 cells from 4 mice) than control (n = 7 cells from 4 mice, P = 0.0006 t-test) (C) Although the GABACR charge transfer (Q) is reduced, the difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.07 t-test) (D) Representative traces of the timecourse of vesicle release estimated using deconvolution analysis from data in (A) are shown. (E) The average D37 of vesicle release from diabetic cells is significantly faster than in control cells (P = 0.006 t-test). (F) There is no difference in the amount of electrically evoked vesicle release onto rod bipolar cell GABACRs (P = 0.77 t-test). (G) The amount of vesicle release that occurred during the early and late phases normalized to the total amount of vesicle release from control and diabetic cells is shown. In diabetic amacrine cells, there was an increase in the amount of vesicle release onto rod bipolar cell GABACRs that occurred during the early phase and a decrease in the amount of release that occurred during the late phase (P = 0.04 t-test). *P < 0.05, †P < 0.01.

Asynchronous release from lateral amacrine cells can occur in two phases—an early phase with a peak in the first 100 ms after a stimulus, and a late phase that occurs after 100 ms until the response returns to baseline.18 Under normal conditions, GABA release onto rod bipolar cell GABACRs occurs predominantly during the late phase. Although the timecourse of GABA release onto GABACRs from diabetic amacrine cells is shortened, the amount of vesicle release is unchanged. It is possible that more release is occurring during the early phase to compensate for reduced asynchronous release. To test this, the early and late phases of GABA release onto rod bipolar cell GABACRs were analyzed. The proportion of vesicle release from diabetic amacrine cells in the early phase was significantly increased (Fig. 1G). In control cells, 7.5 ± 1.2% of total GABA release onto GABACRs occurred during the early phase. In diabetic cells the amount increased to 14.7 ± 3% (P = 0.04 t-test). This was accompanied by significantly fewer vesicles released during the late asynchronous phase of release (P = 0.04). This suggests that reduced evoked GABA release from lateral amacrine cells to rod bipolar cells is due to limited slow GABA release in early diabetes.

GABA Release From Lateral Amacrine Cells is More Susceptible to Ca2+ Buffering in Early Diabetes

Asynchronous release from amacrine cells relies on a global increase in intracellular Ca2+ that can be reduced by Ca2+ buffering with the slow-acting Ca2+ chelator EGTA.19–21,38 Because GABA release is brief in diabetic amacrine cells that inhibit rod bipolar cells, this could be due to a limitation in the widespread increase in intracellular Ca2+ after a stimulus that is required to support asynchronous release. This possibility was tested by recording rod bipolar cell eIPSCs in the presence of EGTA-AM, a membrane permeant analog of the chelator. If the ability of diabetic GABAergic amacrine cells to increase intracellular Ca2+ after a stimulus is impaired, then they will be more vulnerable to Ca2+ buffering by EGTA-AM. Because the internal solution for the rod bipolar cell recordings contained 10 mM EGTA (see Methods), adding 50 μM EGTA-AM is unlikely to significantly alter Ca2+ buffering in the postsynaptic rod bipolar cells.

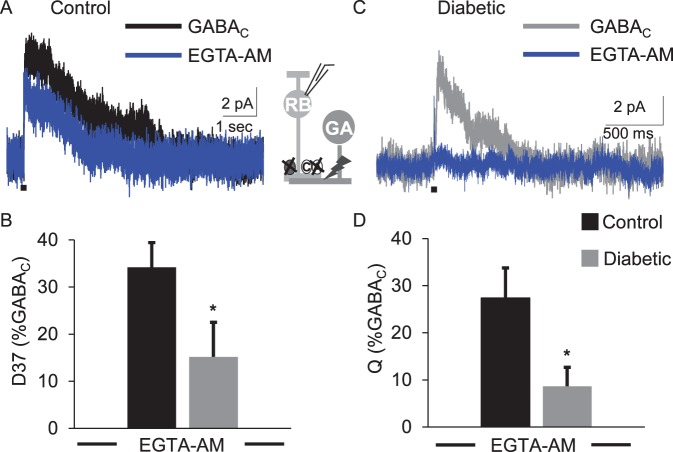

As shown in Figure 2, EGTA-AM reduced GABACR-mediated eIPSCs in both conditions. However, treatment with EGTA-AM more severely affected the diabetic cells (Fig. 2B). EGTA-AM reduced the D37 and Q in diabetic cells significantly more than in control cells (Table 2; Fig. 2, D37 P = 0.05, Q P = 0.03, t-test). The peak amplitude of GABACR eIPSCs in diabetic cells was also decreased more by EGTA-AM in diabetic cells when compared to those recorded in control cells (P = 0.004, Table 2). Consistent with these results, deconvolution analysis showed that GABA release from diabetic amacrine cells was more severely affected (Table 3; Fig. 3). The amount (P = 0.03), timing (P = 0.03), and peak (P = 0.02) of vesicle release in diabetic cells treated with EGTA-AM were reduced more than in control cells. These data indicate that GABAergic amacrine cells that form lateral connections with rod bipolar cells are more susceptible to slow Ca2+ buffering in early diabetes, and may indicate a lack of Ca2+ availability to support asynchronous release.

Figure 2.

GABACR eIPSCs are more susceptible to Ca2+ buffering by EGTA-AM in early diabetes. Representative traces of GABACR eIPSCs from control (A) and diabetic (B) cells, before (black or gray traces) and after (blue trace) treatment with 50 μM EGTA-AM are shown. EGTA-AM significantly decreased the eIPSC D37 (C, P = 0.05 t-test) and charge transfer (D, P = 0.02 t-test) of diabetic cells (n = 8 cells from 5 mice) below the levels measured in control cells (n = 7 cells from 4 mice). All values are normalized to GABACR eIPSCs measured prior to applying EGTA-AM. Black bar: 1-ms stimulus. *P < 0.05.

Table 2.

GABACR eIPSC Values Recorded in the Presence of EGTA-AM

|

eIPSC |

Q (norm) |

D37 (norm) |

Peak (norm) |

n

(Cells) |

Mice |

| Control GABACR EGTA-AM | 27.4 ± 6.4 | 34.2 ± 5.3 | 63.4 ± 8.9 | 8 | 4 |

| Diabetic GABACR EGTA-AM | 8.6 ± 4.0* | 14.2 ± 7.6* | 18.5 ± 9.6† | 8 | 5 |

Data are average values of charge transfer (Q), D37 and peak amplitude normalized (norm) to the value recorded for each cell prior to applying EGTA-AM.

P ≤ 0.05 when compared with control GABACR values (t-test).

P < 0.01 when compared with control GABACR values (t-test).

Table 3.

Average Values for GABA Release Onto GABACRs in the Presence of EGTA-AM

|

Condition |

Vesicles (norm) |

D37 (norm) |

Peak (norm) |

n

(Cells) |

Mice |

| Control GABA release EGTA-AM | 40 ± 10 | 47.3 ± 10.7 | 58 ± 11 | 8 | 4 |

| Diabetic GABA release EGTA-AM | 12.3 ± 4.9* | 14.6 ± 9.4* | 19.2 ± 12.1* | 8 | 5 |

Average values of the amount (vesicles), timing (D37), and peak of vesicle release normalized to values determined by deconvolution analysis are shown. Values are normalized (norm) to vesicle release from each cell that occurred in the absence of EGTA-AM.

P < 0.05 when compared with control GABA release (t-test).

Figure 3.

Electrically evoked GABA release onto rod bipolar cells GABACRs is more severely affected by Ca2+ buffering with EGTA-AM in early diabetes. The timecourse of GABA release onto rod bipolar cell GABACRs from control (A) and diabetic (B) cells was estimated by deconvolution analysis using the eIPSCs in Figure 2. Increased Ca2+-buffering with EGTA-AM reduced the timing (C, P = 0.03 t-test) and amount (D, P = 0.02 t-test) of vesicle release from diabetic cells (n = 8 cells from 5 mice) below the levels measured from control cells treated with EGTA-AM (n = 7 cells from 4 mice). All values are normalized to GABA release onto GABACRs measured prior to applying EGTA-AM. Black bar: 1-ms stimulus. *P < 0.05.

Early Diabetes Decreases GABA Release at the Reciprocal Rod Bipolar Cell-A17 Amacrine Cell Synapse

Reduced GABA release from lateral amacrine cells after direct activation shows diabetes reduces a large component of rod bipolar cell inhibition. Rod bipolar cells also have reciprocal connections with A17 amacrine cells (Fig. 4A, inset) that require direct activation by glutamate release from rod bipolar cells and comprise approximately 50% of rod bipolar cell GABAergic inhibition.19,30 A recent study suggested that diabetes reduced GABA release from A17 amacrine cells, but did not measure inhibition directly23 or in dark-adapted conditions where the rod pathway is more active.30

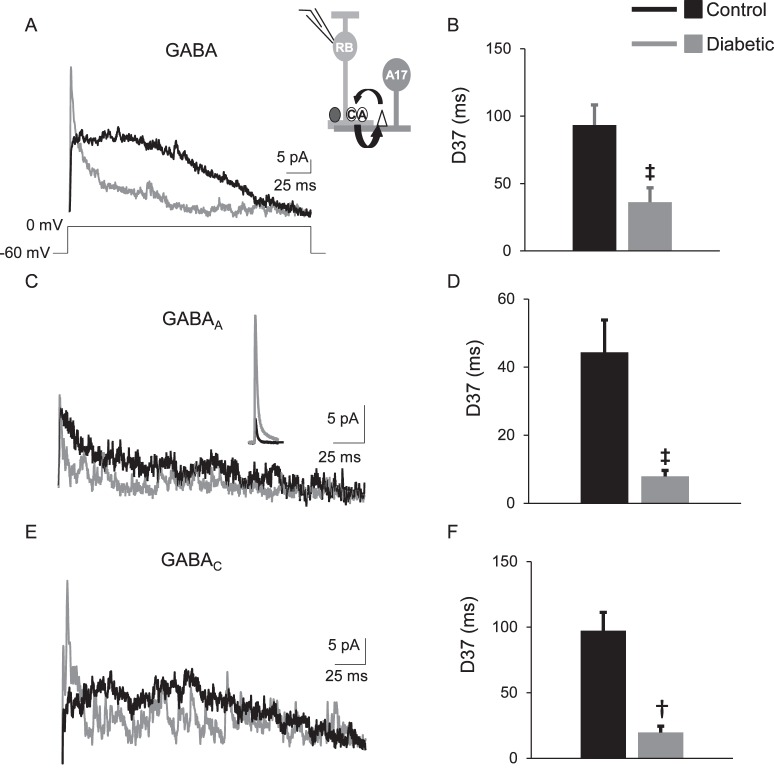

Figure 4.

The timing of feedback inhibition from A17 amacrine cells to rod bipolar cells is shortened after 6 weeks of diabetes. (A) Representative traces of GABAergic fIPSCs averaged from two responses evoked by a 250-ms step from −60 to 0 mV recorded from rod bipolar cells are shown. The inset shows a schematic of the feedback currents, where a rod bipolar cell releases glutamate onto AMPARs (white triangle) on an A17 amacrine cell (A17) and the A17 amacrine cell releases GABA back onto GABACRs (A) and GABAARs (E). The inset in (C) shows the average GABAAR sIPSC used for deconvolution. (B) The D37 for total GABAergic fIPSCs was faster in diabetic cells (n = 13 cells from 5 mice) compared with control cells (n = 12 cells from 6 mice, P = 0.001 t-test). GABAAR (C) and GABACR-mediated (E) fIPSCs are shortened in diabetic cells (GABAAR: n = 11 cells, GABACR: n = 9 cells) compared with control cells (n = 12 cells for both receptor inputs). GABACR (D, P = 0.0001 t-test) and GABAAR-mediated (F, P = 0.005 t-test) fIPSC D37s are faster in diabetic rod bipolar cells. †P < 0.01, ‡P < 0.001.

To determine if rod bipolar cell GABAergic inhibition from A17 amacrine cells is reduced, fIPSCs were recorded from rod bipolar cells following a 250-ms step depolarization from −60 to 0 mV in dark-adapted retinal slices. This evokes glutamate release from the recorded rod bipolar cell that triggers GABA release from reciprocal A17 amacrine cells (Fig. 4). The timing of total GABAergic fIPSCs was shortened in diabetic cells (P = 0.001 t-test, Fig. 4B; Table 4) compared with control cells. However, the charge transfer (P = 0.3) and peak (P = 0.07) were not significantly different although the peak of fIPSCs from diabetic cells (38.2 ± 5.2 pA) on average was larger than that measured in control cells (25.1 ± 4.7 pA). Unlike in lateral rod bipolar cell inhibition, GABAARs mediate a large proportion of rod bipolar cell feedback inhibition,17,36,39 so we recorded both GABAAR- and GABACR-mediated fIPSCs. Isolated GABAAR fIPSCs in diabetic cells had shortened timing (P = 0.005; Fig. 4D) and decreased charge transfer (P = 0.01; Table 4) compared with GABAAR fIPSCs measured in control cells. There was no difference in the GABAAR fIPSC peak amplitude (P = 0.22). Similar to GABAAR fIPSCs, the timing of GABACR fIPSCs was also shortened in diabetic cells (P = 0.0001; Fig. 4F). GABACR fIPSC charge transfer was not significantly different between control and diabetic cells (P = 0.27; Table 4). The peak amplitude of GABACR fIPSCs in diabetic cells was increased compared with control cells (P = 0.03; Table 3), similar to the average total fIPSC, suggesting this average increase is due to an increase in GABACR mediated input.

Table 4.

GABA Receptor fIPSC Values Mediated by A17 Amacrine Cells

|

Condition and Receptor fIPSC |

Q (pA*ms) |

D37 (ms) |

Peak (pA) |

n

(Cells) |

Mice |

| Control GABA | 2231 ± 433 | 93.4 ± 15 | 25.1 ± 4.7 | 12 | 6 |

| Diabetic GABA | 1710 ± 238 | 36.2 ± 10.7† | 38.2 ± 5.2 | 13 | 5 |

| Control GABAAR | 692.8 ± 156.7 | 44.4 ± 9.5 | 11.3 ± 1.3 | 13 | 6 |

| Diabetic GABAAR | 327.5 ± 45.6† | 7.9 ± 1.8† | 11.9 ± 2.6 | 11 | 5 |

| Control GABACR | 1249 ± 182 | 97.4 ± 13.9 | 13.8 ± 1.0 | 12 | 6 |

| Diabetic GABACR | 964 ± 170 | 19.6 ± 4.9‡ | 29.4 ± 5.8* | 9 | 5 |

Average values of fIPSC charge transfer (Q), D37 and peak amplitude for rod bipolar cell GABAAR and GABACRs are shown.

P ≤ 0.05 when compared with values recorded in control cells (t-test).

P ≤ 0.01 when compared with values recorded in control cells (t-test).

P < 0.0001 when compared with values recorded in control cells (t-test).

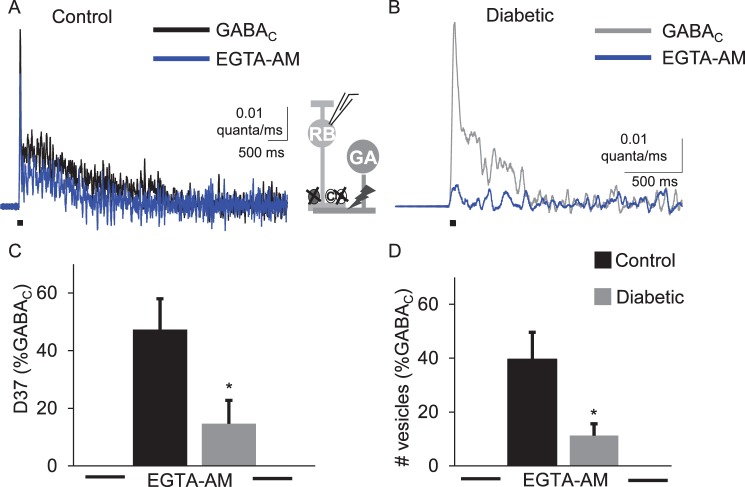

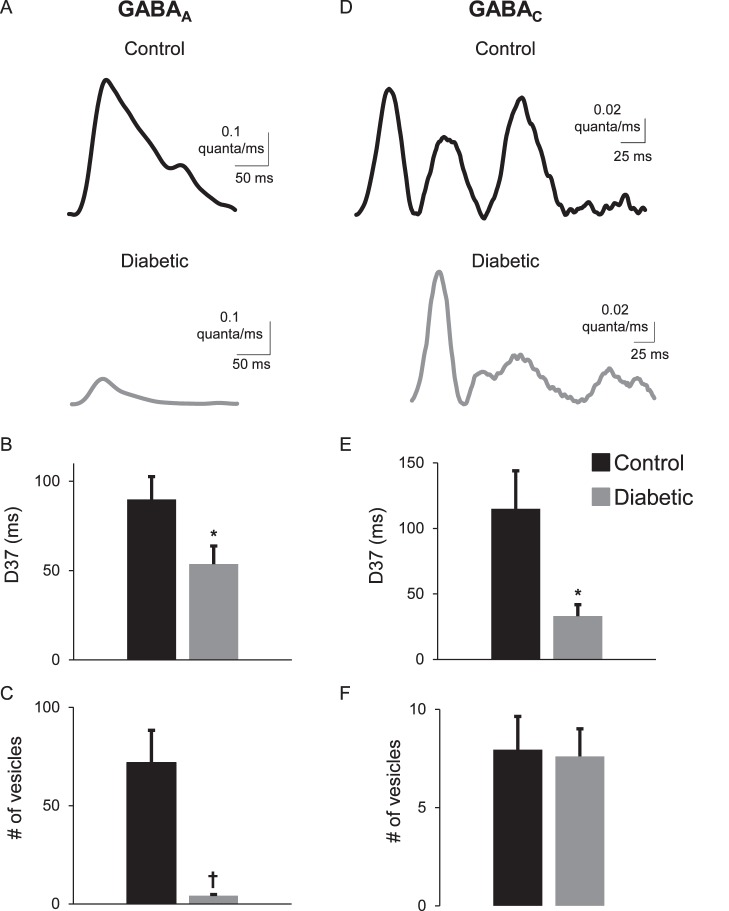

Deconvolution analysis of the fIPSC data was used to determine if early diabetes compromised GABA release from A17 amacrine cells (Figs. 5A, 5C). Previous papers showed that GABAARs and GABACRs are clustered separately in the retina40–42 and that GABACR are located at synapses distal to A17 amacrine cell release sites, so they could potentially be receiving distinct patterns of GABA release. The timing of GABA release onto both GABAARs (P = 0.04) and GABACRs (P = 0.02) was shortened in diabetic cells (Figs. 5B, 5E; Table 5). The peak (P = 0.0003) and amount (P = 0.001) of GABA release onto GABAARs was also reduced (Fig. 5C and Table 5), likely because of the increased peak amplitude of GABAAR-mediated spontaneous IPSCs from diabetic rod bipolar cells.16 For GABA release onto GABACRs, the peak (P = 0.6) and amount (P = 0.9) of release were not different in diabetic cells (Fig. 5F; Table 5). These data show that early diabetes reduces GABA release from A17 amacrine cells onto GABAARs is reduced and release onto GABACRs remains intact although with increased peak and faster timing. Because fIPSCs require glutamate release from rod bipolar cells, it is possible that reduced A17 amacrine cell release reflects decreased excitatory input from rod bipolar cells. To test this, L-EPSCs from A17 amacrine cells were recorded in dark-adapted retinal slices.

Figure 5.

GABA release from A17 amacrine cells is decreased after 6 weeks of diabetes. (A, D) GABA release was estimated using deconvolution of an average GABAAR and GABACR spontaneous IPSC with the corresponding receptor fIPSC from the control and diabetic rod bipolar cells in Figure 4. Representative traces of the timecourse of GABA release from A17 amacrine cells onto rod bipolar cell GABAARs (A) and GABACRs (D) show that timecourse of GABA release was shortened under diabetic conditions. (B, E) The average D37 of vesicle release was faster in diabetic cells for GABA release onto GABAARs (n = 11 cells, P = 0.04 t-test) and GABACR (n = 9 cells, P = 0.02 t-test). (C, F) The amount of vesicle release onto GABAARs (C) was significantly reduced (P = 0.001), but vesicle release onto GABACRs (F) was not different (P = 0.9). *P < 0.05, †P < 0.01.

Table 5.

Values for GABA Release at the A17 Amacrine Cell to Rod Bipolar Cell Synapse

|

Condition |

Vesicles |

D37 (ms) |

Peak |

n

(Cells) |

Mice |

| Control GABAAR | 72 ± 16.4 | 89.8 ± 12.8 | 0.65 ± 0.12 | 13 | 6 |

| Diabetic GABAAR | 4 ± 0.6† | 53.6 ± 10.1* | 0.05 ± 0.008† | 11 | 5 |

| Control GABACR | 8 ± 1.7 | 115 ± 29 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 12 | 6 |

| Diabetic GABACR | 8 ± 1.4 | 33.1 ± 8.6* | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 9 | 5 |

Average values of the amount (vesicles), timing and peak of GABA release from A17 amacrine cells determined by deconvolution analysis are shown.

P < 0.05 when compared with control GABA release values (t-test).

P < 0.01 when compared with control GABA release values (t-test).

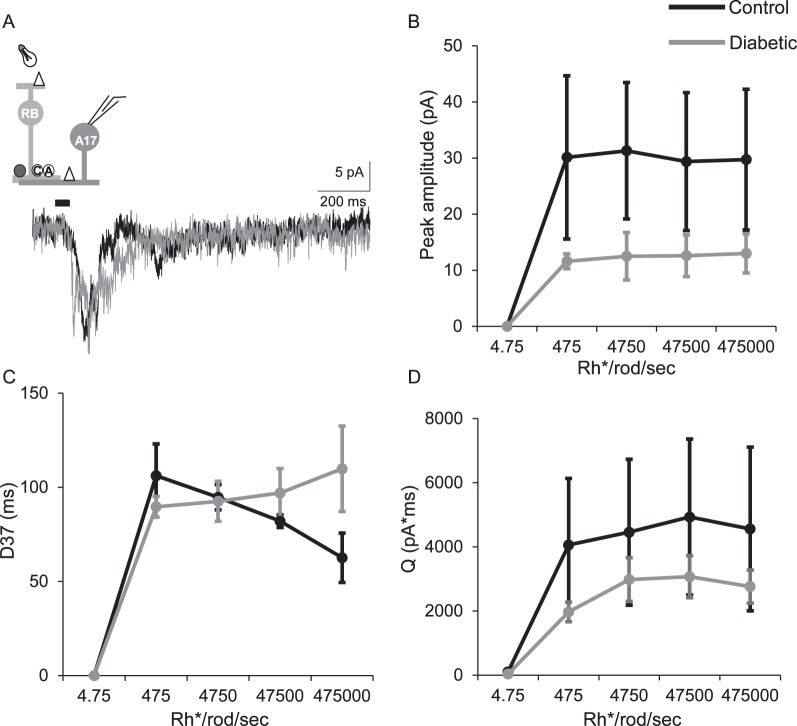

The peak amplitudes and charge transfer of L-EPSCs measured from diabetic A17 amacrine cells (n = 4 cells from 4 mice) compared with control cells (n = 3 cells from 3 mice) were not different (Figs. 6B, 6D; peak: P = 0.7, Q: P = 0.8 two-way repeated-measures ANOVA) although they were on average reduced at all light intensities. The timing was also not different between control and diabetic cells (Fig. 6C; P = 0.2). These data suggest that although subtle differences may be present that decrease output of the A17 amacrine cells onto rod bipolar cells, the differences that result in less vesicle release onto rod bipolar cell from fIPSCs are likely to be primarily internal to the A17 amacrine cells and not from change in inputs.

Figure 6.

Excitatory input from rod bipolar cells to downstream A17 amacrine cells is not significantly different in early diabetes. (A) Representative traces of L-EPSCs averaged from two responses at the maximum light intensity recorded from A17 amacrine cells after a 30-ms light stimulus. The inset shows a schematic of a rod bipolar cell being activated by light and releasing glutamate onto AMPARs (white triangle) on an A17 amacrine cell (A17), which is being recorded. (B, D) The peak amplitudes (B, P = 0.7 two-way repeated-measures ANOVA) and charge transfer (D, P = 0.8) are on average reduced at multiple light intensities in diabetic (n = 4 cells from 4 mice) A17 amacrine cells compared to control (n = 3 cells from 3 mice) but this is not statistically significant. The timing (D37, C) of L-EPSC was similar between control and diabetic cells (P = 0.2).

Discussion

Studies regarding visual complications of diabetes have shown that diabetes compromises signaling between retinal neurons. Here, we show that directly activated retinal GABAergic amacrine cells that inhibit rod bipolar cells have deficits in GABA release that could explain previously measured decreases in light-evoked inhibition in diabetic rod bipolar cells.16 In diabetes, both inhibitory inputs from lateral GABAergic amacrine cells and reciprocal inhibition from A17 amacrine cells are less prolonged than during normal conditions. In diabetic mice, increased Ca2+ buffering more severely affected GABA release from lateral amacrine cells to rod bipolar cells. The change in the timing of GABA release creates an imbalance between the timing of rod bipolar cell excitation and amacrine cell inhibition that affects the ability of the retina to respond properly to light.43

Unlike most neurons that primarily use fast, synchronous vesicle release, asynchronous release is the primary form of release used by some amacrine cells and depends on CICR that prolongs the Ca2+ signal.18–21 Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space precedes CICR, prolonging the intracellular Ca2+ signal.20,22 Ca2+ entry through L-type and N-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels provides most of the initial Ca2+ signal that drives GABA release from lateral amacrine cells onto rod bipolar cell terminals.19,20 Diabetic dorsal root ganglia, nociceptive neurons, and intracardiac ganglion neurons show altered expression of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel subunits and currents.24,25,44 Additionally, a recent study of diabetic A17 amacrine cells23 suggested that glutamate induced Ca2+ entry through Ca2+ permeable (CP)-AMPARs that is required for release from reciprocal A17 amacrine cells17,19 was reduced, which could explain the fIPSC reductions here. CP-AMPARs also mediate part of the GABA release from lateral amacrine cells but the effect of diabetes on CP-AMPARs expressed on lateral GABAergic amacrine cells was not investigated. It is possible that a shared consequence of diabetes among neurons is a change in the expression or composition of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels that reduces Ca2+ entry. This change will likely diminish activation of CICR, thereby limiting release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores.

The reliance on a buildup of intracellular Ca2+ that can persist several hundred milliseconds after a stimulus makes asynchronous release susceptible to buffering by the slow Ca2+ chelator EGTA.45–51 In the presence of EGTA-AM, GABA release in amacrine cells from diabetic animals was nearly abolished, unlike in control animals. The larger percentage of GABA release reduction by EGTA-AM in diabetic animals suggests that early diabetes decreases the prolonged intracellular Ca2+ signal in amacrine cells. It is possible that intracellular mechanisms underlying Ca2+ mobilization from the internal stores in GABAergic amacrine cells malfunction in diabetes. Isolated dorsal root ganglion neurons and dorsal horn neurons in a rat model of diabetes have decreased Ca2+ release from internal stores2,26,52 due to decreased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations after activation of endoplasmic reticulum ryanodine and IP3 receptors just 6 weeks after inducing diabetes.2 This suggests that the reduced evoked GABA release from amacrine cells shown here could be due to similar mechanisms. Ca2+ release from mitochondria, another source of internal Ca2+ stores, is also reduced in some dorsal root ganglion neurons from diabetic mice.53 The reduced vesicle release observed here could also be due to alterations in synaptic vesicle proteins that are involved in synaptic transmission as changes in the expression of synaptic vesicle proteins have been shown in the diabetic retina.54 However, this is unlikely because the total amount of vesicle release onto GABACRs is not decreased and the frequency of spontaneous IPSCs actually increases16 suggesting that the vesicle machinery remains intact.

In the current study, the timing of GABA release was shortened, but the amount of vesicle release onto GABACRs from lateral and reciprocal inputs was not different. It is possible that the decreased timing of GABACR-mediated inhibition reflects a change in the receptor kinetics. GABACRs on isolated diabetic rat rod bipolar cells have increased sensitivity to exogenous GABA,55 suggesting receptor changes. However, kinetic analysis of spontaneous synaptic GABACR currents under diabetic conditions did not suggest differences in GABACR characteristics.16 Another possibility is that cluster sizes of rod bipolar cell GABACRs are reduced. The slow kinetics of GABACRs contribute to the prolonged timing of rod bipolar cell inhibition28 Fewer receptors at the amacrine cell to rod bipolar cell synapse could shorten the timing of rod bipolar cell inhibition. Because morphologic changes in GABACR expression were not investigated the possibility that GABACR clusters are different in early diabetes cannot be ruled out. However, the lack of changes in the peak amplitude of GABACR spontaneous IPSCs suggest that this is unlikely. Alternatively, GABAergic amacrine cells could alter their release mechanisms to compensate for a shortened timecourse of release. Under normal conditions, GABA release from amacrine cells is predominantly asynchronous and has prolonged timing.18,20,21,28 Approximately 90% of electrically evoked GABA release onto GABACRs occurs more than 100 ms after the stimulus.18 In diabetic retinas, there was a slight but significant increase in release during the early phase of GABA release that occurs within 100 ms of the stimulus, which may be enough to maintain the amount of release onto GABACRs at normal levels.

Together these results suggest that diabetes is specifically altering Ca2+ homeostasis and release in amacrine cells in the rod pathway of the diabetic retina. Because neurons in other areas of the brain show similar Ca2+ homeostasis changes,2,26,52 this could be a common mechanism of diabetic dysfunction in neurons. As the rod pathway of the retina seems most susceptible to early diabetes14 these Ca2+ homeostasis malfunctions could be early changes that lead to other diabetic neuron dysfunction causing changes in vision.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Eggers laboratory for helpful comments on this manuscript.

Supported by grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship 3-PDF-2014-105-A-N (JMM; New York, NY, USA); the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) grants R01-EY026027 (EDE) and Cardiovascular Training Grant 2T32HL7249-36 (JMM).

Disclosure: J.M. Moore-Dotson, None; E.D. Eggers, None

References

- 1.Brini M, Cali T, Ottolini D, Carafoli E. Neuronal calcium signaling: function and dysfunction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:2787–2814. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1550-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kruglikov I, Gryshchenko O, Shutov L, Kostyuk E, Kostyuk P, Voitenko N. Diabetes-induced abnormalities in ER calcium mobilization in primary and secondary nociceptive neurons. Pflugers Arch. 2004;448:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satoh E, Takahashi A. Experimental diabetes enhances Ca2+ mobilization and glutamate exocytosis in cerebral synaptosomes from mice. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;81:e14–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostyuk E, Svichar N, Shishkin V, Kostyuk P. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in calcium signalling alterations in dorsal root ganglion neurons of mice with experimentally-induced diabetes. Neuroscience. 1999;90:535–541. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00471-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang TJ, Sayers NM, Fernyhough P, Verkhratsky A. Diabetes-induced alterations in calcium homeostasis in sensory neurones of streptozotocin-diabetic rats are restricted to lumbar ganglia and are prevented by neurotrophin-3. Diabetologia. 2002;45:560–570. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0785-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castilho AF, Liberal JT, Baptista FI, Gaspar JM, Carvalho AL, Ambrosio AF. Elevated glucose concentration changes the content and cellular localization of AMPA receptors in the retina but not in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2012;219:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R, Klein BEK. Diabetes in America 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health;; 1995. Vision disorders in diabetes; pp. 293–337. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonetti DA, Klein R, Gardner TW. Diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1227–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1005073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simo R, Hernandez C;, European Consortium for the Early Treatment of Diabetic Research Group Neurodegeneration is an early event in diabetic retinopathy: therapeutic implications. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:1285–1290. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson GR, Barber AJ. Visual dysfunction associated with diabetic retinopathy. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10:380–384. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masland RH. The fundamental plan of the retina. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:877–886. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masland RH. The neuronal organization of the retina. Neuron. 2012;76:266–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juen S, Kieselbach GF. Electrophysiological changes in juvenile diabetics without retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:372–375. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070050070033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pardue MT, Barnes CS, Kim MK, et al. Rodent hyperglycemia-induced inner retinal deficits are mirrored in human diabetes. Trans Vis Sci Tech. 2014;3(3):6. doi: 10.1167/tvst.3.3.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luu CD, Szental JA, Lee SY, Lavanya R, Wong TY. Correlation between retinal oscillatory potentials and retinal vascular caliber in type 2 diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:482–486. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore-Dotson JM, Beckman JJ, Mazade RE, et al. Early retinal neuronal dysfunction in diabetic mice: reduced light-evoked inhibition increases rod pathway signaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:1418–1430. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chavez AE, Singer JH, Diamond JS. Fast neurotransmitter release triggered by Ca influx through AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Nature. 2006;443:705–708. doi: 10.1038/nature05123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore-Dotson JM, Klein JS, Mazade RE, Eggers ED. Different types of retinal inhibition have distinct neurotransmitter release properties. J Neurophysiol. 2015;113:2078–2090. doi: 10.1152/jn.00447.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chavez AE, Grimes WN, Diamond JS. Mechanisms underlying lateral GABAergic feedback onto rod bipolar cells in rat retina. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2330–2339. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5574-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eggers ED, Klein JS, Moore-Dotson JM. Slow changes in Ca2(+) cause prolonged release from GABAergic retinal amacrine cells. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:709–719. doi: 10.1152/jn.00913.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gleason E, Borges S, Wilson M. Control of transmitter release from retinal amacrine cells by Ca2+ influx and efflux. Neuron. 1994;13:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gleason E, Borges S, Wilson M. Synaptic transmission between pairs of retinal amacrine cells in culture. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2359–2370. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02359.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castilho A, Ambrosio AF, Hartveit E, Veruki ML. Disruption of a neural microcircuit in the rod pathway of the mammalian retina by diabetes mellitus. J Neurosci. 2015;35:5422–5433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5285-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yusaf SP, Goodman J, Gonzalez IM, et al. Streptozocin-induced neuropathy is associated with altered expression of voltage-gated calcium channel subunit mRNAs in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289:402–406. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khomula EV, Borisyuk AL, Viatchenko-Karpinski VY, Briede A, Belan PV, Voitenko NV. Nociceptive neurons differentially express fast and slow T-type Ca(2)(+) currents in different types of diabetic neuropathy. Neural Plast. 2014;2014:938235. doi: 10.1155/2014/938235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zherebitskaya E, Schapansky J, Akude E, et al. Sensory neurons derived from diabetic rats have diminished internal Ca2+ stores linked to impaired re-uptake by the endoplasmic reticulum. ASN Neuro. 2012;4:e00072. doi: 10.1042/AN20110038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aung MH, Park HN, Han MK, et al. Dopamine deficiency contributes to early visual dysfunction in a rodent model of type 1 diabetes. J Neurosci. 2014;34:726–736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3483-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eggers ED, Lukasiewicz PD. Receptor and transmitter release properties set the time course of retinal inhibition. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9413–9425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2591-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keck M, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Cai Q, Hoyer PB, Brooks HL. Hormonal status affects the progression of STZ-induced diabetes and diabetic renal damage in the VCD mouse model of menopause. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F193–F199. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00022.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eggers ED, Mazade RE, Klein JS. Inhibition to retinal rod bipolar cells is regulated by light levels. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:153–161. doi: 10.1152/jn.00872.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosh KK, Bujan S, Haverkamp S, Feigenspan A, Wassle H. Types of bipolar cells in the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:70–82. doi: 10.1002/cne.10985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menger N, Wassle H. Morphological and physiological properties of the A17 amacrine cell of the rat retina. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17:769–780. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800175108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Field GD, Rieke F. Nonlinear signal transfer from mouse rods to bipolar cells and implications for visual sensitivity. Neuron. 2002;34:773–785. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diamond JS, Jahr CE. Asynchronous release of synaptic vesicles determines the time course of the AMPA receptor-mediated EPSC. Neuron. 1995;15:1097–1107. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grimes WN, Zhang J, Graydon CW, Kachar B, Diamond JS. Retinal parallel processors: more than 100 independent microcircuits operate within a single interneuron. Neuron. 2010;65:873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartveit E. Reciprocal synaptic interactions between rod bipolar cells and amacrine cells in the rat retina. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:2923–2936. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.6.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson R, Kolb H. A17: a broad-field amacrine cell in the rod system of the cat retina. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54:592–614. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gleason E, Borges S, Wilson M. Electrogenic Na-Ca exchange clears Ca2+ loads from retinal amacrine cells in culture. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3612–3621. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03612.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eggers ED, Lukasiewicz PD. Interneuron circuits tune inhibition in retinal bipolar cells. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:25–37. doi: 10.1152/jn.00458.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fletcher EL, Koulen P, Wassle H. GABAA and GABAC receptors on mammalian rod bipolar cells. J Comp Neurol. 1998;396:351–365. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980706)396:3<351::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frazao R, Nogueira MI, Wassle H. Colocalization of synaptic GABA(C)-receptors with GABA (A)-receptors and glycine-receptors in the rodent central nervous system. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;330:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0446-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koulen P, Brandstatter JH, Enz R, Bormann J, Wassle H. Synaptic clustering of GABA(C) receptor rho-subunits in the rat retina. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:115–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Protti DA, Di Marco S, Huang JY, Vonhoff CR, Nguyen V, Solomon SG. Inner retinal inhibition shapes the receptive field of retinal ganglion cells in primate. J Physiol. 2014;592:49–65. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.257352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X, Hirano AA, Sun X, Brecha NC, Barnes S. Calcium channels in rat horizontal cells regulate feedback inhibition of photoreceptors through an unconventional GABA- and pH-sensitive mechanism. J Physiol. 2013;591:3309–3324. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.248179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Augustine GJ, Santamaria F, Tanaka K. Local calcium signaling in neurons. Neuron. 2003;40:331–346. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chung C, Raingo J. Vesicle dynamics: how synaptic proteins regulate different modes of neurotransmission. J Neurochem. 2013;126:146–154. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hefft S, Jonas P. Asynchronous GABA release generates long-lasting inhibition at a hippocampal interneuron-principal neuron synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1319–1328. doi: 10.1038/nn1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaeser PS, Regehr WG. Molecular mechanisms for synchronous, asynchronous, and spontaneous neurotransmitter release. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:333–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neher E. Usefulness and limitations of linear approximations to the understanding of Ca++ signals. Cell Calcium. 1998;24:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rozov A, Burnashev N, Sakmann B, Neher E. Transmitter release modulation by intracellular Ca2+ buffers in facilitating and depressing nerve terminals of pyramidal cells in layer 2/3 of the rat neocortex indicates a target cell-specific difference in presynaptic calcium dynamics. J Physiol. 2001;531:807–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0807h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakaba T, Neher E. Quantitative relationship between transmitter release and calcium current at the calyx of held synapse. J Neurosci. 2001;21:462–476. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00462.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verkhratsky A, Fernyhough P. Mitochondrial malfunction and Ca2+ dyshomeostasis drive neuronal pathology in diabetes. Cell Calcium. 2008;44:112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Svichar N, Shishkin V, Kostyuk E, Voitenko N. Changes in mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis in primary sensory neurons of diabetic mice. Neuroreport. 1998;9:1121–1125. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.VanGuilder HD, Brucklacher RM, Patel K, Ellis RW, Freeman WM, Barber AJ. Diabetes downregulates presynaptic proteins and reduces basal synapsin I phosphorylation in rat retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramsey DJ, Ripps H, Qian H. An electrophysiological study of retinal function in the diabetic female rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5116–5124. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]