Phosphorylation of kinetochore proteins destabilizes improper kinetochore–microtubule attachments. Asai et al. find that SET/TAF1, an inhibitor of the PP2A phosphatase, binds shugoshin 2 and corrects erroneous kinetochore–microtubule attachment by maintaining Aurora B kinase activity. Therefore, SET has a key role in establishing chromosome bi-orientation by balancing Aurora B and PP2A activity.

Abstract

The accurate regulation of phosphorylation at the kinetochore is essential for establishing chromosome bi-orientation. Phosphorylation of kinetochore proteins by the Aurora B kinase destabilizes improper kinetochore–microtubule attachments, whereas the phosphatase PP2A has a counteracting role. Imbalanced phosphoregulation leads to error-prone chromosome segregation and aneuploidy, a hallmark of cancer cells. However, little is known about the molecular events that control the balance of phosphorylation at the kinetochore. Here, we show that localization of SET/TAF1, an oncogene product, to centromeres maintains Aurora B kinase activity by inhibiting PP2A, thereby correcting erroneous kinetochore–microtubule attachment. SET localizes at the inner centromere by interacting directly with shugoshin 2, with SET levels declining at increased distances between kinetochore pairs, leading to establishment of chromosome bi-orientation. Moreover, SET overexpression induces chromosomal instability by disrupting kinetochore–microtubule attachment. Thus, our findings reveal the novel role of SET in fine-tuning the phosphorylation level at the kinetochore by balancing the activities of Aurora B and PP2A.

Introduction

Aurora B is an important regulator of mitotic cell division, serving as the catalytic core of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC), which includes three regulatory proteins: inner centromere protein (INCENP), survivin, and borealin (Carmena et al., 2009). Aurora B is required for accurate chromosome segregation and cytokinesis. Aurora B is enriched at different intracellular locations, from which it regulates cell division: it localizes initially at the inner centromere, and subsequently at the anaphase spindle midzone (Terada et al., 1998; Carmena et al., 2009). Aurora B kinase activation occurs during mitosis through a two-step mechanism. In the first, Aurora B is partially activated by interaction with INCENP and is autophosphorylated at threonine 232 (Thr232) with its activation T loop (Honda et al., 2003; Yasui et al., 2004). In the second step, Aurora B–mediated phosphorylation of INCENP at the TSS motif induces complete Aurora B activation (Bishop and Schumacher, 2002). In contrast, protein phosphatase (PP) 2A negatively regulates Aurora B activity by removing its phosphorylated Thr232 (Sugiyama et al., 2002; Yasui et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2008).

For proper chromosome segregation, the interaction between kinetochores and microtubules is regulated by the balance between the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of kinetochore substrates (Walczak et al., 2010; Lampson and Cheeseman, 2011). During prometaphase and metaphase, sister kinetochores are attached by microtubules emanating from opposite spindle poles (bi-orientation). Aurora B is enriched at the inner centromeres to phosphorylate the kinetochore substrates and thereby destabilize kinetochore–microtubule attachment. In contrast, PP1 and PP2A, which accumulate at centromeres or kinetochores, stabilize kinetochore–microtubule attachment by counteracting phosphorylation at the kinetochore (Liu et al., 2009, 2010; Tanaka, 2010; Welburn et al., 2010; Foley et al., 2011; Meadows et al., 2011; Rosenberg et al., 2011). It has been shown that when PP2A is bound by BUBR1, a mitotic checkpoint component at kinetochores, it contributes to the stabilization of kinetochore–microtubule attachment (Suijkerbuijk et al., 2012).

Aurora B–mediated substrates positioned at the outer kinetochore are highly phosphorylated on mis-aligned kinetochores and are dephosphorylated when centromeres bi-orient at metaphase (Keating et al., 2009; Welburn et al., 2010). Aurora B constitutively phosphorylates substrates that are closer to the inner centromere, but not substrates located at the periphery of the outer kinetochore, such as NDC80, at metaphase. The spatial separation model proposes that Aurora B phosphorylates the outer kinetochore substrates in a distance-dependent manner due to kinetochore accessibility of Aurora B. Aurora B is decreased when tension across kinetochore pairs is established (Lampson and Cheeseman, 2011). In contrast, the PP2A heterotrimeric complex containing the B56 subunit (PP2A-B56) is distributed from the centromeres to the kinetochores that have come under tension, leading to the dephosphorylation of the kinetochore substrates phosphorylated by Aurora B and Plk1 (Foley et al., 2011; Vallardi et al., 2019).

Mammals have two shugoshin-like proteins, Sgo1 and Sgo2, both of which associate with PP2A as well as with CPC in the inner centromeres (Kitajima et al., 2006; Riedel et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2006; Tsukahara et al., 2010). Sgo1-bound PP2A dephosphorylates mitotic cohesin and thereby prevents cohesin dissociation during prometaphase, whereas Sgo2-bound PP2A plays a crucial role in protecting meiotic cohesin at centromeres in meiosis I (Lee et al., 2008; Llano et al., 2008; Rattani et al., 2013). Although Sgo2 knock out mice are viable, somatic Sgo2 functions have been identified using cultured cells. Depletion of Sgo2 causes defects in chromosome alignment as well as a partial loss of cohesion only in metaphase-arrested cells. Sgo2 acts as a versatile centromeric adaptor that recruits PP2A, CPC, MAD2, and mitotic centromere-associated kinesin (MCAK; Kitajima et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2007; Tanno et al., 2010; Orth et al., 2011). Notably, the majority of the PP2A pool at centromeres is produced by Sgo2, but its role in cohesion protection is marginal in mitotic cells (Kitajima et al., 2006; Tanno et al., 2010). Given that Sgo1-bound PP2A counteracts Aurora B kinase activity at centromeres (Meppelink et al., 2015), it is possible that Sgo2-bound PP2A also plays a physiological role in attenuating Aurora B kinase activity.

SET/TAF1/I2PP2A was originally identified as the SET-CAN fusion gene associated with acute myeloid leukemia (von Lindern et al., 1992; Adachi et al., 1994; Saito et al., 2008). SET shows structural homology to members of the nucleosome assembly protein (NAP) 1 family. SET/TAF1 contains at least two splicing variants, α and β (Nagata et al., 1998), and has multiple functions, including acting as a histone chaperone (Kato et al., 2007; Muto et al., 2007) and in gene transcription (Compagnone et al., 2000), chromosome condensation, sister chromatid cohesion (Chambon et al., 2013), and sister chromatid resolution (Krishnan et al., 2017). SET forms an inhibitory protein complex with PP2A (Li et al., 1995, 1996). The PP2A tumor suppressor is inactivated through the aberrant activity of SET in several different leukemias including CML, AML, JAK2V617F+ myeloproliferative neoplasms, and Philadelphia-positive B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Neviani and Perrotti, 2014). SET is also one of the interactors in the shugoshin protein complex in meiotic and mitotic cells (Kitajima et al., 2006; Chambon et al., 2013; Krishnan et al., 2017). SET is proposed to regulate sister chromatid separation by removing centromeric shugoshin and linker histone at the interchromatid axis (Krishnan et al., 2017). Moreover, it is suggested that SET localizes and inhibits PP2A at centromeres in meiosis II, which may ensure proper chromatid separation (Chambon et al., 2013; Qi et al., 2013; Sanyal et al., 2013). However, the regulatory mechanisms of PP2A by SET at the kinetochore/centromere remain largely unknown.

In the present study, we show that the major centromeric pool of SET is recruited through interaction with Sgo2, and maintains Aurora B activity by counteracting PP2A in mitotic cells. In contrast, SET dissociates with Sgo2 from centromeres depending on an increase in the distance between kinetochore pairs, when microtubule-derived tension is applied to the kinetochore. These results suggest that SET maintains Aurora B kinase activity during prophase and prometaphase, and its dissociation activates PP2A phosphatase activity at kinetochores during metaphase to stabilize kinetochore–microtubule attachment. Furthermore, impaired Aurora B activation correlates with chromosome misalignment, mis-segregated chromosomes, failure of cytokinesis, and aneuploidy, a hallmark of cancer cells (Tatsuka et al., 1998; Terada et al., 1998; Adams et al., 2001; Ditchfield et al., 2003; Muñoz-Barrera and Monje-Casas, 2014). Overexpression of Aurora B promotes the continuous disruption of chromosome–microtubule attachments, even when sister chromatids are correctly bi-oriented (Tatsuka et al., 1998; Muñoz-Barrera and Monje-Casas, 2014). We also show that overexpression of SET-CAN induces chromosome abnormalities via the hyperactivation of Aurora B kinase activity. Our results provide mechanistic insight into how SET regulates kinetochore–microtubule attachment and proper chromosome segregation, and the mechanism of the chromosome abnormalities caused by SET-CAN.

Results

C-terminal domain of SET is required for the direct interaction with Sgo2 and the centromeric localization of SET

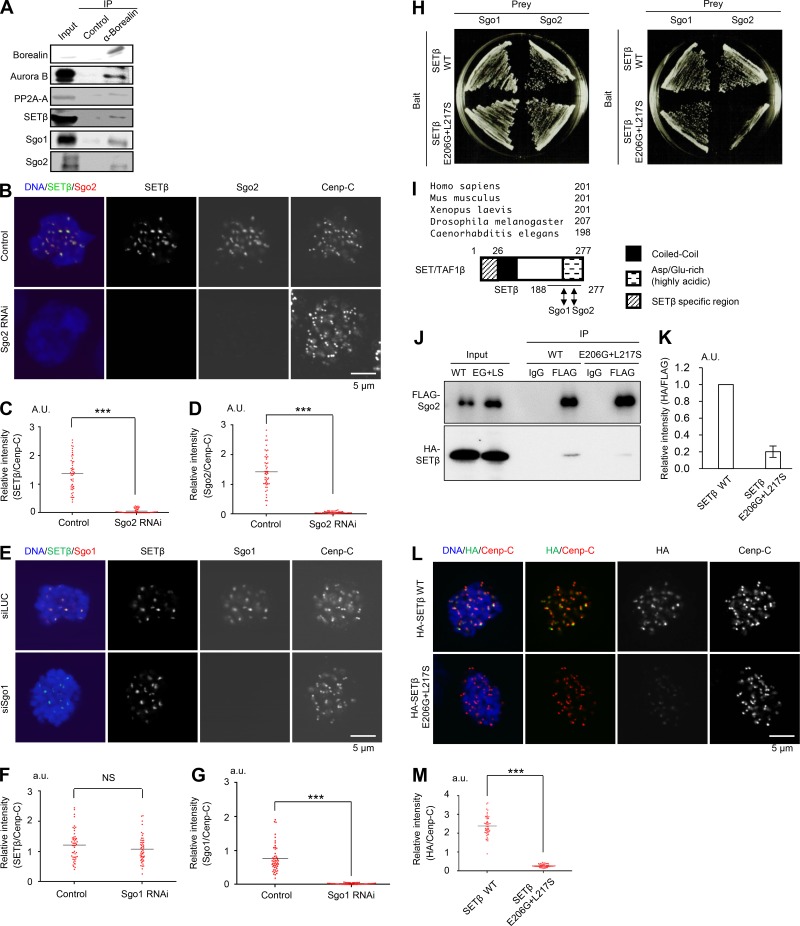

Previous tandem mass spectrometry analyses identified SET/TAF1 associations with Sgo1, Sgo2, the PP2A heterotrimeric complex containing the catalytic subunit (PP2A-C), the scaffold subunit (PP2A-A), and PP2A-B56 (Kitajima et al., 2006; Krishnan et al., 2017). To examine further the possibility that SETβ/TAF1 localizes at the inner centromere with shugoshin and CPC, we performed immunoprecipitation analysis using antibodies against borealin, a component of the CPC. In addition to Sgo1 and Sgo2 (Kitajima et al., 2006), borealin co-precipitated SETβ with PP2A-A and Aurora B in mitotically synchronized HeLa cells (Fig. 1 A), confirming that SETβ associates with components of the inner centromere including CPC.

Figure 1.

SETβ localizes at the centromere mainly on Sgo2 and forms a complex with Aurora B and PP2A-A. (A) Mitotic cell extracts were prepared from HeLa cells synchronized by treatment with nocodazole following double thymidine block and release. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-borealin or control mouse IgG antibodies and were analyzed by immunoblot using the individual antibodies. (B–G) HeLa cells treated with Sgo2 or Sgo1 siRNA were immunostained with anti-SETβ, anti-Sgo2, anti-Sgo1, or anti–Cenp-C antibodies and DAPI. Relative fluorescence intensities of Sgo2 or Sgo1 and SETβ toward anti–Cenp-C antibodies were quantified at five centromeres in each cell. Each bar represents the mean (n = 50 centromeres from 10 cells, 5 centromeres per cell; Mann-Whitney U test; ***, P < 0.001). Scale bars, 5 μm. (H) Yeast two-hybrid assay indicates that point mutations in SETβ on E206 to G and L217 to S (E206G+L217S) result in reducing the binding affinity between SETβ and Sgo2, but not Sgo1. (I) Sequence alignment of SETβ indicates that the domain that interacts with Sgo2 is highly preserved from Caenorhabditis elegans to Homo sapiens. Arrowheads indicate the mutations isolated in yeast two-hybrid screening, which abolish the interaction with Sgo2. The schematic diagram of SETβ indicates the interaction domains with human Sgo1 and human Sgo2. Coiled-coil domain (Zaytsev et al., 2016) and Asp/Glu-rich (highly acidic) regions (dotted) of SETβ are shown. See Fig. S1 G, too. (J and K) 293T cells were co-transfected with FLAG-Sgo2 and HA-SETβ WT or HA-SETβ E206G+L217S mutant defective for interaction with Sgo2. Immunoprecipitates were obtained from cell extracts by anti-FLAG or control IgG antibodies and analyzed by immunoblot using anti-HA antibody for detection of SETβ. Bars represent SD (n = 3 independent experiments). (L and M) Signals for HA-SETβ and Cenp-C were examined in SET-siRNA–treated HeLa-1 (CIN−) cells expressing RNAi-resistant HA-SETβ WT or E206G+L217S defective for interaction with Sgo2, which is arrested at prometaphase by colcemid. Graph shows the fluorescent intensity of HA-SETβ/Cenp-C at centromeres. Each bar represents the mean (n = 50 centromeres from 10 cells, 5 centromeres per cell; Mann-Whitney U test; ***, P < 0.001). Scale bar, 5 μm.

Immunostaining showed that SETβ disperses throughout the cytoplasm from the nucleoplasm after breakdown of the nuclear envelope, and localizes strongly at the inner centromere with Sgo2 in prometaphase (Fig. S1 A). SETα, which may function like SETβ, shows a similar protein level (Nagata et al., 1998) and localization as SETβ (Fig. S1 B). We next examined the possibility that SETβ interacts directly with Sgo1 or Sgo2 to localize at the centromere. As a result, the centromeric localization of SETβ was severely impaired in cells treated with Sgo2 siRNA, while only slightly impaired in Sgo1 siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 1, B–G and Fig. S1 C). Furthermore, the in vitro binding assay indicated that Sgo2 binds to SETβ more strongly than does Sgo1 (Fig. S1 D), suggesting that centromeric SETβ localization largely depends on Sgo2.

To evaluate the significance of the interaction between SETβ and Sgo2 in vivo, we next isolated a SETβ mutant defective in interaction with Sgo2. Yeast two-hybrid assays revealed that the C-terminal region of SETβ (188–277 aa) interacts with the N-terminal region of Sgo2 (1–331 aa) despite the interaction of SETβ with the middle and C-terminal region of Sgo1 (177–527 aa; Fig. S1, E–G). Consistent with these results, the SETβ E206G+L217S mutant, which is defective for interaction with Sgo2 but not with Sgo1, was isolated by PCR-based mutagenesis and yeast two-hybrid screening (Fig. 1, H and I). Immunoprecipitation revealed that the E206G+L217S mutation weakens the interaction between SETβ and Sgo2 in vivo (Fig. 1, J and K). The fact that the E206G+L217S mutation on SETβ, which allows the interaction with Sgo1 (Fig. 1 H), strongly inhibited the centromeric localization of SETβ (Fig. 1, L and M) strongly indicates that SETβ localizes at centromeres mainly on Sgo2 but not Sgo1.

Although SETβ is known to associate directly with PP2A (Li et al., 1995, 1996), SETβ remained associated with centromeres in cells in which endogenous Sgo2 was replaced with Sgo2-N9A, a mutant protein defective in the interaction with PP2A-B56α (Fig. S1, H and I). These results suggest that SETβ localizes at centromeres through direct interaction with Sgo2 rather than with PP2A on Sgo2.

SETβ is required for chromosome alignment during mitosis, but not for the protection of centromeric cohesion

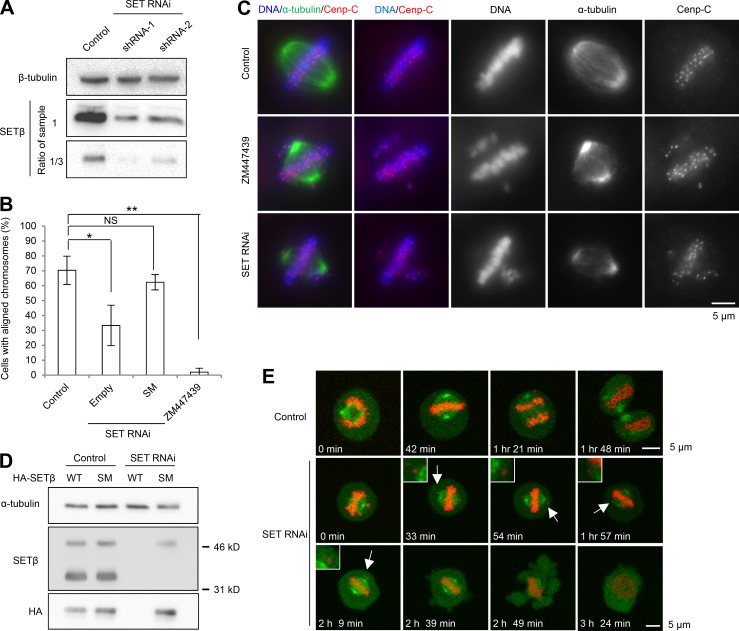

To assess directly the importance of SET during mitosis, we constructed two different short hairpin (sh) RNAs (shRNA-1 and -2) against both SETα and SETβ and used them to infect HeLa cells, which resulted in a considerable reduction in endogenous SET proteins (Fig. 2 A). We next examined the effects of SET depletion using shRNA-1. Immunostaining revealed that SET depletion resulted in a 3.6-fold increase in the fraction of cells with misaligned chromosomes (Fig. 2 B), as observed in ZM447439-treated cells (Fig. 2 C), implying a functional overlap of SET with Aurora B. To ensure that this phenotype is not due to off-target effects, we performed a rescue experiment by generating an shRNA-resistant version of SETβ (SM, silent mutation; Fig. 2 D). Expression of SETβ SM largely rescued the alignment defect, confirming that this phenotype is due to SET depletion and that SET contributes to the chromosome alignment in metaphase (Fig. 2 B). Additionally, live-cell imaging of HeLa cells stably expressing both histone H2B-mRFP and EB1-GFP also revealed chromosome misalignment in SET-depleted cells, but not control cells (Fig. 2 E). In accordance, SET-depleted cells released from monastrol exhibited a mitotic delay or arrest, whereas control cells quickly exited metaphase in the first 2 h (Fig. S2, A and B). These analyses suggest that the initial mitotic arrest in SET-RNAi cells is due to the defect in chromosome alignment. Furthermore, the SETβE206G+L217S mutant, which is defective for interaction with Sgo2, could not rescue the defects in chromosome alignment and mitotic delay, suggesting that SET functions in chromosome alignment require interaction with Sgo2 (Fig. S2, C and D).

Figure 2.

SETβ is required for chromosome alignment during mitosis. (A) HeLa cells were infected with lentivirus containing shLuciferase (control) or shSET (SET RNAi) against SETα/β, and were analyzed by immunoblot with anti-SETβ and anti-β-tubulin antibodies. (B) Control or SET-RNAi cells were arrested in mitosis by nocodazole treatment for 6 h and released into MG132 for 2 h with or without ZM447439. Each bar represents SD (n = 3 independent experiments, 100 cells per experiment; Welch’s t test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (C) Chromosome alignment defects in SET-RNAi cells or ZM447439-treated cells. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Cell extracts prepared from cells transfected with HA-SETβ WT or SETβ shRNA-resistant SM after shRNA infection were immunoblotted for anti-HA, anti-SETβ and anti-α-tubulin antibodies. (E) Mitotic cells stably expressing H2B-mRFP and GFP-EB1 were live-imaged after treatment with shRNA-targeting SETα/β or luciferase (control). Arrows indicate misaligned chromosomes. Scale bars, 5 μm.

We next investigated the possibility that SET contributes to the protection of centromeric cohesion. Although both Sgo1 and PP2A-A RNAi cells showed premature sister chromatid separation, SET depletion or overexpression did not result in centromeric separation (Fig. S2, E–G). These results suggest that SET might not be relevant to the regulation of PP2A on Sgo1 for cohesion protection at centromeres. However, we also observed a low level (8%) of inhibition of chromatid arm resolution in SET-depleted cells (Fig. S2 H; Krishnan et al., 2017).

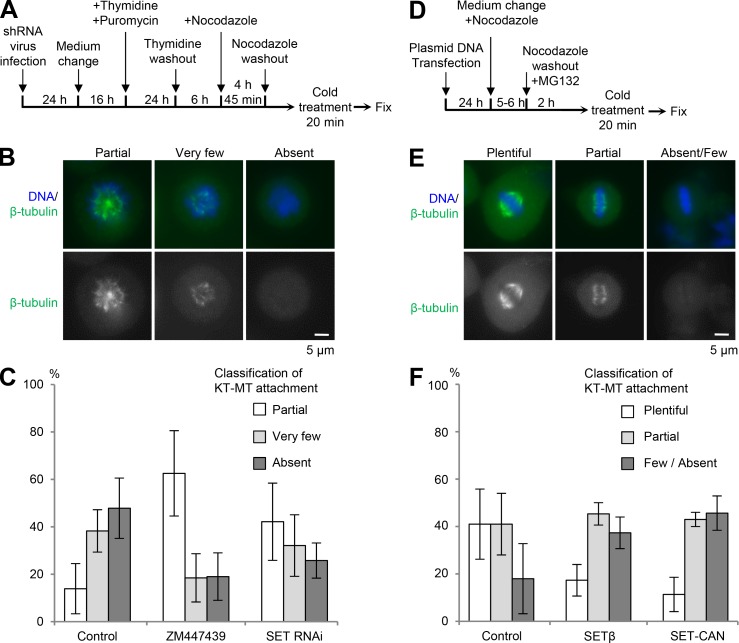

SETβ is required for correct kinetochore–microtubule attachment during mitosis

To examine whether SET RNAi impairs kinetochore–microtubule attachment, we assayed for K-fibers using the cold treatment method (Foley et al., 2011). First, we scored the absence of K-fibers in prometaphase cells that had not yet entered metaphase (Fig. 3, A–C). Almost all mitotic control cells contained very few or no K-fibers. In contrast, both SET RNAi and ZM447439 treatment increased the fraction of mitotic cells exhibiting partially formed K-fibers (Fig. 3 C). Next, we used transient nocodazole arrest and then released cells into medium containing the proteasome inhibitor (MG132) for 2 h to accumulate metaphase cells containing stable kinetochore–microtubule attachments (Fig. 3, D–F). Almost all control cells contained plentiful or partial K-fibers (Fig. 3 F). In contrast, ∼40% of cells overexpressing SETβ or SET-CAN, a fusion oncoprotein, had kinetochores lacking K-fibers. These results suggest that, like Aurora B, SETβ is required for the destabilization of kinetochore–microtubule attachment. Moreover, ZM447439 treatment prevented the destabilization of K-fibers caused by SETβ overexpression (Fig. S3, A and B), suggesting that SET contributes to Aurora B activity.

Figure 3.

SETβ is required for proper kinetochore–microtubule (KT–MT) attachment. (A–C) K-fiber defects in SET-depleted cells during prometaphase. Cells were synchronized by thymidine block and release, then arrested in prometaphase by nocodazole treatment for 4 h, and released for 45 min with or without ZM447439 before cold treatment and fixation as indicated in the schematic. (D–F) Overexpression of SET disturbs stable K-fiber formation in metaphase cells. Cells were transfected with control, HA-SETβ or HA-SET-CAN plasmids arrested in mitosis by nocodazole treatment for 6 h, and released into MG132 for 2 h before cold treatment and fixation as shown in the schematic. (B and E) The fixed cells were immunostained with anti-β-tubulin antibody (green) and DAPI. Images show examples of plentiful, partial, very few, absent, or absent/few K-fibers. Scale bars, 5 μm. (C and F) Graph shows the frequency of prometaphase cells (C) or metaphase cells (F) with plentiful, partial, very few, absent, or absent/few K-fibers. Each bar represents SD (C: n = 3 independent experiments, >100 cells per experiment; F: n = 3 independent experiments, 100 cells per experiment).

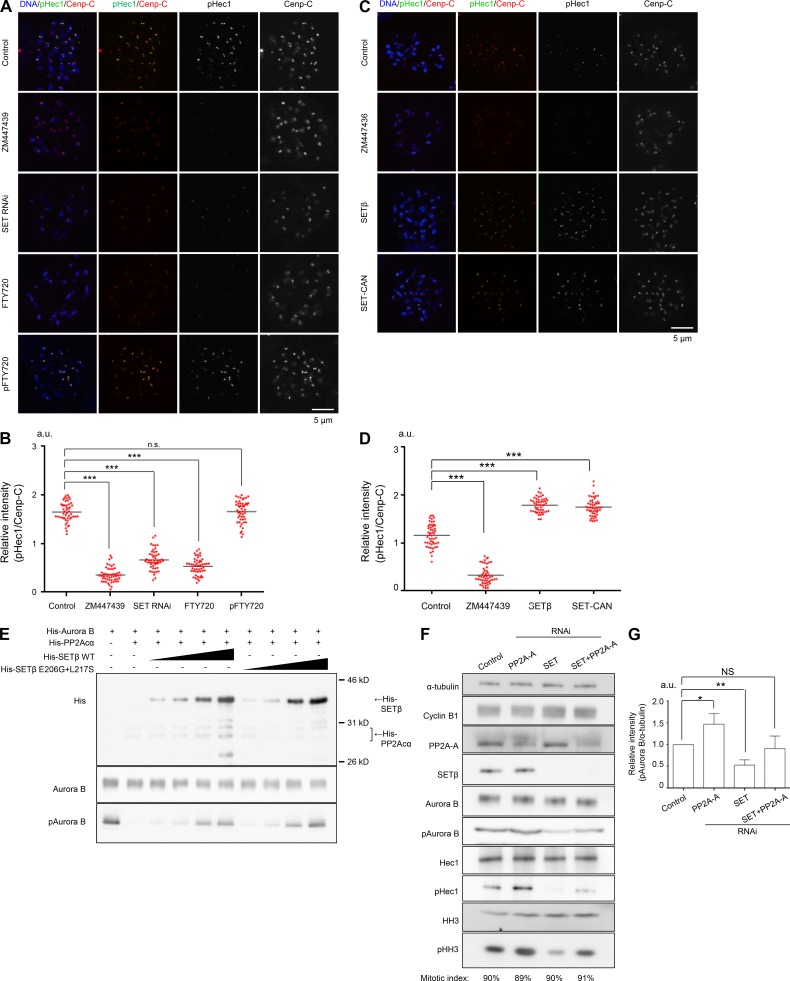

SETβ is required for the activation of Aurora B kinase by inhibiting PP2A phosphatase activity

The foregoing results suggest the possibility that SET might regulate Aurora B activity at centromeres. To investigate this, we examined the phosphorylation status of the kinetochore protein Hec1 (DeLuca et al., 2011), whose phosphorylation by Aurora B decreases kinetochore–microtubule binding affinity (Foley et al., 2011). In prometaphase cells, the level of Hec1 phosphorylation was dramatically decreased in both SET-depleted and ZM447439-treated cells as compared with controls (Fig. 4, A and B; and Fig. S4 A), although the depletion or overexpression of SET protein did not affect the amount of Hec1 protein at the kinetochores (Fig. S4 B). To assess the contribution of SET to the regulation of Aurora B through its PP2A inhibition, we used FTY720, a chemical inhibitor that inhibits SET activity by interfering with the interaction between SET and PP2A (Saddoughi et al., 2013). FTY720 treatment reduced the Hec1 phosphorylation level (Fig. 4, A and B; and Fig. S4 A), whereas the addition of pFTY720, an inactive version of FTY720, did not. In contrast, the overexpression of SET, but not the E206G+L217S mutant, increased the phosphorylation level of Hec1 (Fig. 4, C and D; and Fig. S4, C–E). Consistently, the histone H3 Ser10 phosphorylation level of mitotic chromatin was also reduced by SET depletion, or treatment with ZM447439 or FTY720, but not pFTY720 (Fig. S4, F and G). Furthermore, the addition of FTY720, but not pFTY720, in prometaphase cells reduced the autophosphorylation level of Aurora B at Thr232, and the phosphorylation levels of both Hec1 and histone H3 at Ser10 (Fig. S4 H). These results strongly suggest that SET is required to maintain the kinase activity of Aurora B at centromeres by inhibiting PP2A phosphatase activity. Additionally, like SETβ, overexpression of SETα increased the phosphorylation level of Hec1 (Fig. S4, I and J) suggesting that SETβ and SETα have redundant functions at centromeres. Together, these analyses clearly indicate that the centromeric pool of SET is required to maintain the level of phosphorylation of Aurora B kinetochore substrates.

Figure 4.

SETβ is required for Aurora B activation by inhibiting PP2A phosphatase activity. (A and B) HeLa cells infected with control or shSET viruses were synchronized at prometaphase with colcemid for 1.5 h and further treated with or without ZM447439 for 30 min and FTY720 or pFTY720 for 1 h. Cells were immunostained with anti–p(phospho)Hec1 antibody, anti–Cenp-C antibody, and DAPI. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C and D) HeLa cells transfected with HA-SETβ or HA-SET-CAN were synchronized at prometaphase with colcemid for 1.5 h and further treated with or without ZM447439 for 30 min. Cells were immunostained with anti–pHec1, anti–Cenp-C antibodies, and DAPI. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B and D) Relative fluorescence intensities of pHec1 toward Cenp-C were quantified at five kinetochore pairs per cell. Bars represent the average values. Scatter plot (B and D: n = 50 kinetochore pairs from 10 cells, 5 kinetochore pairs per cell; Mann-Whitney U test; ***, P < 0.001). (E) SETβ inhibits dephosphorylation of T232 on Aurora B by PP2A in vitro. 10 ng of His6-Aurora B was incubated with or without 20 ng of recombinant His8-PP2A-Cα/PP2A-A and 30–1,000 ng of His6-SETβ, and phosphorylation was detected by immunoblotting using antibody against the Aurora B pT232 autophosphorylation site. (F) HeLa cells infected with shLuc (control) or shSET viruses and further transfected with PP2A-A or Luc (control) siRNA were synchronized at prometaphase with nocodazole. Then, mitotic cells were collected by shake-off and analyzed by immunoblot using the indicated antibodies. Numbers under the figure indicate the mitotic index. (G) Relative intensities of pAurora B/α-tubulin of F were quantified. Bars represent SD (n = 3 independent experiments; Welch’s t test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (A–D and F and G) Pre-existing mitotic cells were removed by preshake-off before synchronization with colcemid or nocodazole to make the length of mitotic arrest the same between control cells and cells with a manipulated amount of SET protein.

Given that PP2A negatively regulates Aurora B activity by removing phosphorylated Thr232 on Aurora B in vitro (Sugiyama et al., 2002; Yasui et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2008), we hypothesized that SETβ might positively regulate Aurora B activity by inhibiting PP2A phosphatase activity. To investigate this possibility, we performed in vitro kinase assays using purified recombinant His6-Aurora B, His8-PP2A-Cα and His6-SETβ. The results indicate that PP2A indeed dephosphorylates the autophosphorylation site (Thr232) of Aurora B, and that SETβ can rescue Aurora B kinase activity by inhibiting PP2A in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4 E). We further examined their relationship in vivo by immunoblot. As expected, we found that depletion of PP2A restored Aurora B kinase activity in SET-depleted cells (Fig. 4, F and G; and Fig. S4, K and L). Taken together, these results strongly support the notion that SET is required for the maintenance of Aurora B kinase activity by counteracting PP2A.

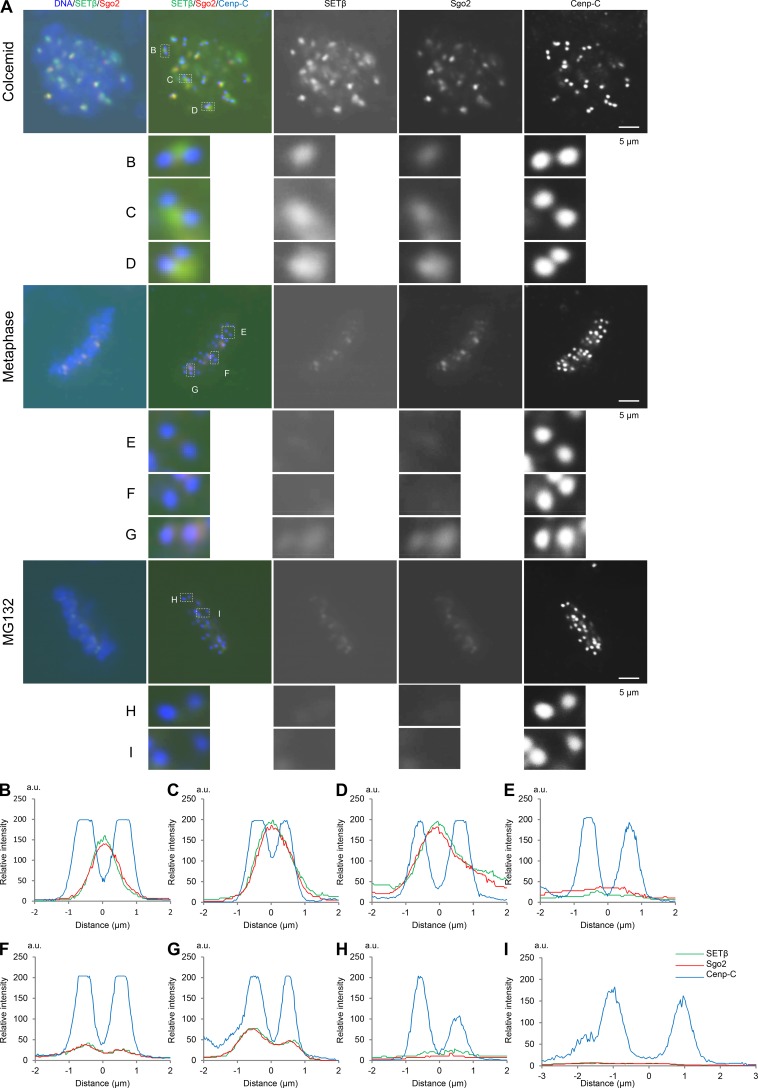

SETβ co-localizes at inner centromeres with Sgo2 in prometaphase, but dissociates from the centromeres of aligned chromosomes in metaphase

Previous reports have shown that Sgo2 redistributes from the inner centromeres in prometaphase to sister kinetochores in metaphase (Lee et al., 2008). Since SETβ localizes at centromeres depending on Sgo2 (Fig. 1, B–D, L, and M), we analyzed the dynamics of the localization of these proteins at centromeres in HeLa cells from prometaphase to metaphase. Consistent with previous data, microscopy analysis revealed Sgo2 to be enriched at the inner centromeres of chromosomes that had not congressed to the metaphase plate (Fig. 5 A, top and B–D), and then distributed from the centromeres to each sister kinetochore in metaphase cells (Fig. 5 A, middle and E–G) and MG132-treated cells (Fig. 5 A, bottom and H and I). Quantification data also indicated that the kinetochore localization of both SETβ and Sgo2 in metaphase is significantly reduced as compared with their inner centromeric localization in prometaphase (Fig. S5, A–C). Importantly, the localization of SETβ, but not PP2A (Welburn et al., 2010), was reduced dependent on the increase in the distance between kinetochore pairs and the establishment of tension across kinetochore pairs (Fig. S5, D–F). These data provide an attractive model in which the dissociation of SETβ from the centromere/kinetochore ensures the timely activation of PP2A and thereby the inactivation of Aurora B, leading to the stabilization of the kinetochore–microtubule on the bi-oriented chromosome.

Figure 5.

The SETβ signal leaves centromeres in metaphase. (A) HeLa cells released from RO3306 and then treated with colcemid (top and B–D), with MG132 (bottom and H and I), or not treated (middle and E–G) were fixed and stained with anti-SETβ (green), Sgo2 (red), and Cenp-C (blue) antibodies. DAPI was used to visualize DNA. Kinetochore pairs in white enclosures are shown in large scale. Scale bars, 5 μm. (B–I) Line scans of individual sister kinetochores/centromeres in the white enclosures are shown from left to right.

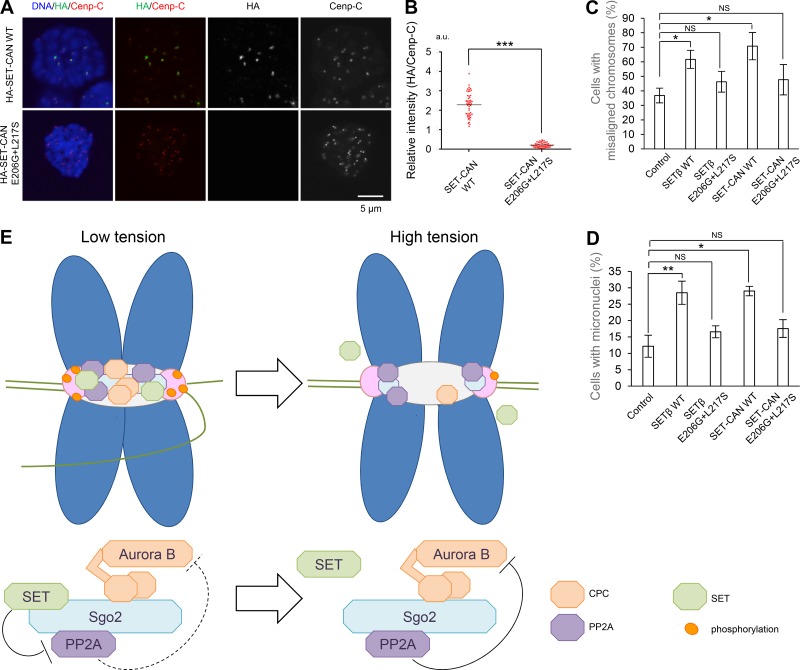

Overexpression of SETβ and SET-CAN induces chromosomal misalignment and abnormal chromosome segregation, which require direct interaction with Sgo2

PP2A phosphatase activity is functionally inhibited as a consequence of the overexpression of SET or SET-CAN in several leukemic cells (Neviani and Perrotti, 2014), although the molecular mechanisms by which SET and SET-CAN function as oncogenes are not well understood. Because the activity of Aurora B kinase at the inner centromere is required to destabilize kinetochore–microtubule attachment (Lampson and Cheeseman, 2011; Muñoz-Barrera and Monje-Casas, 2014), and its dysregulation results in chromosomal instability (CIN; Cimini et al., 2001; Thompson and Compton, 2008; Bakhoum et al., 2009), we hypothesized that SET or SET-CAN might drive Aurora B to generate a dysregulated hyperactive state of kinase activity, and thereby induce chromosomal abnormalities in cancer cells. In accordance with this notion, like SET, SET-CAN also associates with centromeres in an Sgo2-dependent manner (Fig. 6, A and B), and its overexpression could impair kinetochore–microtubule attachment by activating Aurora B kinase activity (Fig. 3, E and F; and Fig. 4, C and D). Indeed, overexpression of SET-CAN, but not the E206G+L217S mutant, induced chromosomal misalignment (Fig. 6 C). Because an increase in the frequency of micronuclei reflects the occurrence of chromosome breaks and abnormal chromosome segregation, which is associated with a future risk of cancer in humans (Bonassi et al., 2005), we next examined whether the ectopic expression of either SETβ or SET-CAN has any effects on micronuclei frequency (Fig. 6 D). Strikingly, both SETβ and SET-CAN expression resulted in a 2.3-fold increase in the fraction of cells containing micronuclei as compared with control cells. Notably, the E206G+L217S mutations nearly entirely abolished the centromere localization of SETβ and SET-CAN and the increased frequency of the alignment defect and micronuclei in both SETβ- and SET-CAN–overexpressing cells. These results suggest that the dysregulated kinase activity of Aurora B may contribute to the mechanism underlying the chromosome abnormality caused by SET or SET-CAN expression.

Figure 6.

Overexpression of SETβ or SET-CAN induces chromosome misalignment and chromosomal abnormalities in an Sgo2-dependent manner. (A and B) Signals for HA-SETβ and Cenp-C were examined in SET-siRNA–treated HeLa-1 (CIN−) cells expressing RNAi-resistant HA-SET-CAN WT or E206G+L217S defective for interaction with Sgo2, which was arrested at prometaphase by colcemid treatment. Graph shows the fluorescent intensity of HA-SET-CAN/Cenp-C at centromeres. Each bar represents the mean (n = 50 centromeres from 10 cells, 5 centromeres per cell; Mann-Whitney U test; ***, P < 0.001). Scale bar, 5 μm. (C and D) HeLa-1 (CIN−) cells arrested by nocodazole treatment after transfection with HA (control), HA-SETβ WT, HA-SETβ E206G+L217S, SET-CAN WT, or SET-CAN E206G+L217S were further arrested with MG132 after nocodazole wash out and examined by immunostaining with anti-β-tubulin antibody and ACA. Graph shows cells with misaligned chromosomes (C) and cells with micronuclei (D). Each bar represents SD (n = 3 independent experiments, >60 cells per experiment; Welch’s t test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (E) Schematic model showing how SET maintains Aurora B activity (low tension) and the dissociation of SET from centromeres induces PP2A activation for the formation of stable microtubule–kinetochore attachment (high tension).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that SET/TAF1, a PP2A inhibitor protein, contributes to the regulation of Aurora B kinase activity by inhibiting PP2A phosphatase. During mitosis, Aurora B is activated by interaction with INCENP and autophosphorylation at Thr232 with its activation T loop (Honda et al., 2003; Yasui et al., 2004). PP2A inactivates Aurora B kinase activity by removing the phosphorylated Thr232 (Fig. 4 E; Sugiyama et al., 2002; Yasui et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2008). Our in vitro kinase assay revealed that SET can rescue Aurora B kinase activity by inhibiting PP2A (Fig. 4 E). Furthermore, we also verified that SET plays a characteristic role in chromosome alignment by protecting Aurora B kinase activity from PP2A-mediated inactivation (Fig. 4, E–G).

In somatic cells, Sgo1-bound PP2A, despite its small amount, plays an exclusive role in cohesion protection, whereas the function of Sgo2-bound PP2A, which is abundant at centromeres, has remained largely elusive. It is known that Sgo2 acts as a centromeric adaptor that recruits PP2A, CPC, MAD2, and MCAK (Kitajima et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2007; Tanno et al., 2010; Orth et al., 2011). Thus, it is possible that SET regulates chromosome alignment by influencing the functions of Sgo2.

A recent study showed that SET binds Sgo2 and promotes its disassembly from centromeres during anaphase, suggesting that SET acts as a chaperone for evicting Sgo2 (Krishnan et al., 2017). Although the mitotic delay might be caused by the impaired resolution of chromosome arms in SET-depleted cells, it is unlikely that the delay is caused solely by the defects in Sgo2 eviction, which occur late after anaphase onset (Chambon et al., 2013).

Here we show that the centromeric pool of SET, which mostly binds to Sgo2, plays an important role in attenuating Sgo2-bound PP2A activity and thereby activating Aurora B kinase at centromeres during prometaphase. A recent study showed that the overexpression of Sgo1 causes excessive PP2A accumulation at centromeres, leading to a reduction in Aurora B activity (Meppelink et al., 2015). Thus, Sgo1 and Sgo2 possess a common function in attenuating Aurora B activity, although Sgo2 might be predominant under physiological conditions.

Aurora B decreases when tension across kinetochore pairs is established (Lampson and Cheeseman, 2011). In contrast, PP2A-B56 is distributed from the centromeres to the kinetochores that have come under tension, leading to dephosphorylation of the kinetochore substrates (Foley et al., 2011). The geometry model proposes that bi-orientation pulls the kinetochores away from the Aurora B zone, leading to the stabilization of microtubule–kinetochore attachment (Liu et al., 2009; Khodjakov and Pines, 2010; Tanaka, 2010; Lampson and Cheeseman, 2011; Foley and Kapoor, 2013). The above model is also supported by a recent report showing the bi-stability of the Aurora B-phosphatase system (Zaytsev et al., 2016). Based on this model, our data suggest an attractive model in which SET fine-tunes the balance of phosphorylation at kinetochores (Fig. 6 E). Aurora B removes the erroneously attached microtubules in prometaphase by phosphorylating kinetochore components that mediate attachments (Cheeseman and Desai, 2008). In contrast, PP2A regulates the formation of a stable kinetochore–microtubule attachment in metaphase (Maldonado and Kapoor, 2011). In prometaphase, both Aurora B and PP2A seem to be recruited to the inner centromeres partially through direct interaction with Sgo2, and, therefore, PP2A might inhibit Aurora B activity by dephosphorylating its autophosphorylation site (Sugiyama et al., 2002; Yasui et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2008). When inter- and intra-kinetochore tension is low, SET maintains Aurora B kinase activity by attenuating the suppressive action of PP2A on Aurora B. However, when tension is established during the formation of chromosome bi-orientation in metaphase, SET is released from centromere/kinetochore with Sgo2 by an unknown mechanism. Accordingly, Sgo2, together with PP2A, moves toward kinetochores more efficiently than Sgo1 in metaphase, although both shugoshin proteins localize near kinetochores after prolonged metaphase arrest (Lee et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2013, 2015). We thus propose that the tension-dependent dissociation of SET from the centromeres ensures the timely formation of stable K-fibers by activating Sgo2-associated PP2A phosphatase at the kinetochores (Fig. 6 E).

Chromosome mis-segregation in mitosis may contribute to tumorigenesis. Increased Aurora B activity causes a continuous disruption of kinetochore–microtubule attachments and spindle instability, leading to an increase in the frequency of whole chromosome gain or loss (Muñoz-Barrera and Monje-Casas, 2014). We previously reported that Aurora B overexpression is frequently observed in several human tumor cell lines, and its ectopic expression strongly induces chromosomal abnormalities in normal diploid human cell lines (Tatsuka et al., 1998; Terada et al., 1998). In this study, the overexpression of SET-CAN, but not the E206G+L217S mutant, which is defective for interaction with Sgo2 and activation of Aurora B, provokes serious mitotic defects that lead to chromosome abnormalities (Fig. 6 D). Thus, the dysregulation of Aurora B caused by the expression of SET or SET-CAN might contribute to the incidence of malignancy in patients with acute leukemia. Our study provides a novel link between SET on Sgo2 and the phosphoregulation of centromeres, and, therefore, is useful for future studies on CIN in human cells.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for immunofluorescence and immunoblot: Anti-SET/TAF1 (KM1725, KM1712, and KM1720; Nagata et al., 1998), Anti-hSgo1 (Kitajima et al., 2005), hSgo2 (Kitajima et al., 2006), HA (sc-7329 and sc-805 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 3F10 from Roche Diagnostics), Aurora B (611082; Becton Dickinson), pAurora A (T288)/B (T232; 2914S; Cell Signaling), borealin (M147-3; MBL), PP2A-A (sc-6112; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Hec1 (GTX70268; Gene Tex) and Hec1 phospho Ser 55 (GTX70017; Gene Tex), cyclin B1 (sc-245; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-histone H3 Ser 10 (06–570; Millipore), β-tubulin (T4026; Sigma), α-tubulin (T9026; Sigma), His (M136-3; MBL), and Cenp-C (PD030; MBL) antibodies. Anti-centromere antibody (ACA) was provided by Y. Takasaki (Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan). For immunofluorescence, secondary antibodies (Invitrogen Alexa Fluor) were used at 1:400. For immunoblotting, secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology or Wako) were used at 1:2,000.

Plasmids and baculoviruses

SETα, SETβ and NAPL1 were amplified by PCR and cloned into the Kpn1-Xho1 site of pCMV/HA by Ligation Mix (Takara Bio). HA-SETα and β were cloned into the EcoR1 site of pCAGGS by In-Fusion (Invitrogen). HA-SET-CAN was amplified from pCHA-SET-CAN/Nup214 (Saito et al., 2016) and cloned into the EcoR1 site of pCAGGS by In-Fusion. pGEX/Sgo1 (Kitajima et al., 2005) and pGEX/Sgo2 were as described (Kitajima et al., 2006; Bakhoum et al., 2009). For yeast two-hybrid assay, the constructs of SETβ, NAPL1, Sgo1, and Sgo2 derivatives were amplified by PCR and cloned into pGBKT7 as bait (for SETβ and Sgo2) and pGADT7 as prey (for SETβ, NAPL1, Sgo1, and Sgo2). The SETβ E206G+L217S mutation was generated by random mutagenesis and screened by yeast two-hybrid assay. For random mutations, ExTaq was used in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MnCl2, and 0.6 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate mix. The cDNA of Aurora B was amplified from the HeLa cell cDNA and cloned into pFast Bac HTB (Invitrogen). Mutagenesis was performed using a PrimeSTAR Mutagenesis Basal Kit (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. pFast Bac PP2A-A (A subunit) and PP2Acα (C subunit) were provided by T. Ikehara (National Fisheries University, Yamaguchi, Japan). A recombinant PP2A protein complex with phosphatase activity as a holoenzyme was purified in a baculovirus expression system according to the method described by Ikehara et al. (2006).

For shSETα/β resistance, inverse PCR was performed by using the following primers: first PCR sense, 5-′TGAGGACGAGGGTGAAGAAGATGAAGA-3′; first PCR antisense, 5′-TCACCCTCATCCTCATCCCCTTCTTCG-3′; second PCR sense, 5′-CGAGGGCGAGGAAGATGAAGATGATGA-3′; second PCR antisense, 5′-TCTTCCTCGCCCTCGTCCTCATCCCCT-3′.

RNAi and generation of lentivirus

Synthetic siRNAs of Sgo1 (Kitajima et al., 2005), Sgo2 (Kitajima et al., 2006), and PP2A-A (Kitajima et al., 2006) were transfected into HeLa cells with the transfection reagent Lipofectamine RNAi max (Invitrogen). siRNA transfection was performed as described (Lee et al., 2008). For SET RNAi, we used the pLKO.1 (Addgene) vector containing shRNA sequences (pLKO.1-shSET).

The indicated primers were annealed and cloned into pLKO.1 vector Age1-EcoR1 site: shSET#1 sense, 5′-CCGGGAGGATGAAGGTGAAGAAGATCTCGAGATCTTCTTCACCTTCATCCTCTTTTTG-3′; shSET#1 antisense ,5′-AATTCAAAAAGAGGATGAAGGTGAAGAAGATCTCGAGATCTTCTTCACCTTCATCCTC-3′; shSET#2 sense, 5′-CCGGTCGAGTCAAACGCAGAATAAACTCCTCGAGTTTATTCTGCGTTTGACTCGATTTTTG-3′; and shSET#2 antisense, 5-′AATTCAAAAATCGAGTCAAACGCAGAATAAACTCGAGTTTATTCTGCGTTTGACTCGA-3′.

pLKO.1-shSET or pLKO.1 shLuciferase (Abe et al., 2016) control was co-transfected with pCMV⊿8.2 and pVSV-G to 293T cells and cultured for ≥2 d. Lentiviruses containing shSET or shLuciferase were collected and used to infect HeLa cells.

Cell culture, treatment, and transfection

HeLa and 293T cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin (1:100; Wako) at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. The HeLa-1 CIN− cell line was selected as a clone in which chromosome segregation errors are less frequent (provided by M. Ohsugi (Tokyo University, Tokyo, Japan)).

For cell synchronization, thymidine (Sigma), nocodazole (Calbiochem), colcemid (Gibco), the Eg5 inhibitor monastrol (Calbiochem), RO3306 (Sigma), and MG132 (Megraw et al., 2011) were used at 2.5 mM, 100 ng/ml, 100 ng/ml, 10 μM, 6–8 μM, and 10 μM, respectively. For Aurora B inhibition, ZM447439 (AstraZeneca) was used at 5 μM. The cells were selected with 2.0–3.3 ng/ml puromycin, and 400 μg/ml G418. Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf)9 cells were cultured in Grace medium (Gibco) containing penicillin-streptomycin, 10% FBS, 2.6 g/L Bacto Tryptose Phosphate Broth (Becton Dickinson), 3.3 g/L Bact Yeast Extract (BD), 3.3 g/L lactalbumin enzymatic hydrolysate (Sigma), and f68 (1:100; Gibco) at pH 6.0–6.4 and 27°C. For protein purification, Sf9 cells were cultured under gyratory conditions without FBS and f68.

For plasmid DNA transfection, BioT (Bioland Scientific LLC), Lipofectamin3000 (Invitrogen), or polyethyleneimine were used.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

For immunofluorescence microscopy of SETα/β, HA-SET, and HA-SET-CAN at the centromere, cells were cultured on coverslips with Cell-Tak (Corning), treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min before fixation with 1% PFA-0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min and then treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. The cells were then blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 15 min, incubated with diluted primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, and then incubated with secondary antibodies at 37°C for 1 h. Finally, DNA was stained with 3 μM DAPI (Sigma; Megraw et al., 2011).

For analysis of phosphorylation on Hec1 S55, cells were cultured on coverslips, incubated in ×4 PBS at 37°C for 20 min, and then treated with 1% PFA-0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. The cells were then blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 15 min, incubated with diluted primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, and then incubated with secondary antibodies at 37°C for 1 h. Finally, DNA was stained with 3 μM DAPI (Sigma; Megraw et al., 2011).

For analysis of phosphorylation on HH3 S10, cells were cultured on coverslips, treated with 1% PFA-0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and then treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. The cells were then blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 15 min, incubated with diluted primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, and then incubated with secondary antibodies at 37°C for 1 h. Finally, DNA was stained with 3 μM DAPI (Sigma; Megraw et al., 2011).

For analysis of K-fibers, the cells were incubated at 4°C for 20 min in DMEM containing 10% FBS and then fixed with cold methanol. For other experiments, cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS or cold methanol. Cells were blocked in 1% BSA-0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS at 37°C for 1 h and then treated with primary antibody in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight or 37°C for 30 min before incubation with secondary antibody in blocking buffer at 37°C for 30 min.

For the experiment shown in Fig. S2 G, chromosome spreading was performed as described by Yamagishi et al. (2008).

Analysis of immunofluorescence was performed on a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse TE2000-E; Nikon) or FV-1000 (Olympus) with a ×100 objective.

Live imaging

Mitotic HeLa cells stably expressing H2B-mRFP and GFP-EB1 on glass-bottom plates coated with poly-d-lysine (MatTek Corporation) at 37°C were live-imaged after treatment with shRNA-targeting SETα/β or luciferase (control), and filmed on a confocal microscope (FV-1000-D Fluoview; Olympus) using a ×100 objective.

Immunoprecipitation

For analysis of the centromeric complex containing SET, CPC, PP2A, and shugoshin, immunoprecipitation with cross-linker Dithiobis succinimidyl propionate was performed as described (Tsukahara et al., 2010). The proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred onto an Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore), and detected by immunoblot.

Binding assay

GST-fused or His-fused proteins were expressed from bacterial cultures or from baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells and purified with Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen) or glutathione-sepharose 4B (GE), respectively. GST-Sgo1 or GST-Sgo2 were mixed with His6-SETβ and incubated in binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) at 4°C for 30 min. The beads were then washed three times with binding buffer. The bead-bound proteins were detected by immunoblot or Coomassie brilliant blue.

Phosphatase assay

For the experiment shown in Fig. 4 E, His6-SETβ WT or E206G+L217S (30–1,000 ng) and His8-PP2A-Cα (20 ng) with PP2A-A were pre-incubated in phosphatase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 1 mM MnCl2, and 1 mM DTT) at 30°C for 15 min. Then, His6-Aurora B (10 ng) was added and further incubated at 30°C for 60 min. Phosphorylation was analyzed by immunoblot using anti-Aurora B phospho T232 antibody.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

pGBKT7 and pGADT7 plasmids were transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae AH109 strain as described in the Yeastmaker Yeast Transformation System 2 (Invitrogen). Plates lacking both adenine and histidine, or lacking all of adenine, histidine, leucine, and tryptophan, were used as selective media.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of statistical significance was performed by the Student’s t test, Welch’s t test, or Mann-Whitney U test using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism version 6.03 (GraphPad Software).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that SET localizes at centromeres through direct interaction with Sgo2 during mitosis. Fig. S2 shows that SET depletion causes mitotic delay following chromosome misalignment. Fig. S3 shows that Aurora B inactivation stabilizes K-fibers, counteracting SETβ overexpression. Fig. S4 shows that SETβ is required for the phosphorylation of Aurora B substrates. Fig. S5 shows that the SETβ signal at centromere/kinetochore weakens in metaphase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Yasunari Takasaki and Tomoya Kitajima (RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research, Kobe, Japan) for antibodies, Tsuyoshi Ikehara for His8-PP2A-Cα baculovirus, and Miho Ohsugi for HeLa-1 CIN− cells. We thank all the members of the Terada laboratory for their help.

Y. Terada was partially supported by the Terada Memorial Foundation, Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance Welfare Foundation, and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: Y. Tanno, K. Fukuchi, Y. Terada, and Y. Asai designed the experiments and wrote the paper. K. Fukuchi, Y. Tanno, Y. Asai, S. Koitabashi-Kiyozuka, T. Kiyozuka, Y. Nada, T. Koizumi, A. Watanabe, and R. Matsumura carried out essentially all the experiments. S. Koitabashi-Kiyozuka and T. Kiyozuka contributed to the live-cell imaging. Y. Terada, K. Nagata, and Y. Watanabe analyzed the data.

References

- Abe Y., Sako K., Takagaki K., Hirayama Y., Uchida K.S., Herman J.A., DeLuca J.G., and Hirota T.. 2016. HP1-assisted Aurora B kinase activity prevents chromosome segregation errors. Dev. Cell. 36:487–497. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi Y., Pavlakis G.N., and Copeland T.D.. 1994. Identification and characterization of SET, a nuclear phosphoprotein encoded by the translocation break point in acute undifferentiated leukemia. J. Biol. Chem. 269:2258–2262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R.R., Carmena M., and Earnshaw W.C.. 2001. Chromosomal passengers and the (aurora) ABCs of mitosis. Trends Cell Biol. 11:49–54. 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01880-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhoum S.F., Genovese G., and Compton D.A.. 2009. Deviant kinetochore microtubule dynamics underlie chromosomal instability. Curr. Biol. 19:1937–1942. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop J.D., and Schumacher J.M.. 2002. Phosphorylation of the carboxyl terminus of inner centromere protein (INCENP) by the Aurora B Kinase stimulates Aurora B kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27577–27580. 10.1074/jbc.C200307200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonassi S., Ugolini D., Kirsch-Volders M., Strömberg U., Vermeulen R., and Tucker J.D.. 2005. Human population studies with cytogenetic biomarkers: Review of the literature and future prospectives. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 45:258–270. 10.1002/em.20115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena M., Ruchaud S., and Earnshaw W.C.. 2009. Making the Auroras glow: Regulation of Aurora A and B kinase function by interacting proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21:796–805. 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambon J.P., Touati S.A., Berneau S., Cladière D., Hebras C., Groeme R., McDougall A., and Wassmann K.. 2013. The PP2A inhibitor I2PP2A is essential for sister chromatid segregation in oocyte meiosis II. Curr. Biol. 23:485–490. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman I.M., and Desai A.. 2008. Molecular architecture of the kinetochore-microtubule interface. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:33–46. 10.1038/nrm2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimini D., Howell B., Maddox P., Khodjakov A., Degrassi F., and Salmon E.D.. 2001. Merotelic kinetochore orientation is a major mechanism of aneuploidy in mitotic mammalian tissue cells. J. Cell Biol. 153:517–527. 10.1083/jcb.153.3.517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagnone N.A., Zhang P., Vigne J.L., and Mellon S.H.. 2000. Novel role for the nuclear phosphoprotein SET in transcriptional activation of P450c17 and initiation of neurosteroidogenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 14:875–888. 10.1210/mend.14.6.0469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca K.F., Lens S.M., and DeLuca J.G.. 2011. Temporal changes in Hec1 phosphorylation control kinetochore-microtubule attachment stability during mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 124:622–634. 10.1242/jcs.072629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditchfield C., Johnson V.L., Tighe A., Ellston R., Haworth C., Johnson T., Mortlock A., Keen N., and Taylor S.S.. 2003. Aurora B couples chromosome alignment with anaphase by targeting BubR1, Mad2, and Cenp-E to kinetochores. J. Cell Biol. 161:267–280. 10.1083/jcb.200208091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley E.A., and Kapoor T.M.. 2013. Microtubule attachment and spindle assembly checkpoint signalling at the kinetochore. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14:25–37. 10.1038/nrm3494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley E.A., Maldonado M., and Kapoor T.M.. 2011. Formation of stable attachments between kinetochores and microtubules depends on the B56-PP2A phosphatase. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:1265–1271. 10.1038/ncb2327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda R., Körner R., and Nigg E.A.. 2003. Exploring the functional interactions between Aurora B, INCENP, and survivin in mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:3325–3341. 10.1091/mbc.e02-11-0769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Feng J., Famulski J., Rattner J.B., Liu S.T., Kao G.D., Muschel R., Chan G.K., and Yen T.J.. 2007. Tripin/hSgo2 recruits MCAK to the inner centromere to correct defective kinetochore attachments. J. Cell Biol. 177:413–424. 10.1083/jcb.200701122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikehara T., Shinjo F., Ikehara S., Imamura S., and Yasumoto T.. 2006. Baculovirus expression, purification, and characterization of human protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunits α and β. Protein Expr. Purif. 45:150–156. 10.1016/j.pep.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K., Miyaji-Yamaguchi M., Okuwaki M., and Nagata K.. 2007. Histone acetylation-independent transcription stimulation by a histone chaperone. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:705–715. 10.1093/nar/gkl1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating P., Rachidi N., Tanaka T.U., and Stark M.J.. 2009. Ipl1-dependent phosphorylation of Dam1 is reduced by tension applied on kinetochores. J. Cell Sci. 122:4375–4382. 10.1242/jcs.055566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodjakov A., and Pines J.. 2010. Centromere tension: A divisive issue. Nat. Cell Biol. 12:919–923. 10.1038/ncb1010-919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima T.S., Hauf S., Ohsugi M., Yamamoto T., and Watanabe Y.. 2005. Human Bub1 defines the persistent cohesion site along the mitotic chromosome by affecting Shugoshin localization. Curr. Biol. 15:353–359. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima T.S., Sakuno T., Ishiguro K., Iemura S., Natsume T., Kawashima S.A., and Watanabe Y.. 2006. Shugoshin collaborates with protein phosphatase 2A to protect cohesin. Nature. 441:46–52. 10.1038/nature04663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S., Smits A.H., Vermeulen M., and Reinberg D.. 2017. Phospho-H1 decorates the inter-chromatid axis and is evicted along with Shugoshin by SET during mitosis. Mol. Cell. 67:579–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampson M.A., and Cheeseman I.M.. 2011. Sensing centromere tension: Aurora B and the regulation of kinetochore function. Trends Cell Biol. 21:133–140. 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Kitajima T.S., Tanno Y., Yoshida K., Morita T., Miyano T., Miyake M., and Watanabe Y.. 2008. Unified mode of centromeric protection by shugoshin in mammalian oocytes and somatic cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 10:42–52. 10.1038/ncb1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Guo H., and Damuni Z.. 1995. Purification and characterization of two potent heat-stable protein inhibitors of protein phosphatase 2A from bovine kidney. Biochemistry. 34:1988–1996. 10.1021/bi00006a020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Makkinje A., and Damuni Z.. 1996. The myeloid leukemia-associated protein SET is a potent inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A. J. Biol. Chem. 271:11059–11062. 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Vader G., Vromans M.J., Lampson M.A., and Lens S.M.. 2009. Sensing chromosome bi-orientation by spatial separation of aurora B kinase from kinetochore substrates. Science. 323:1350–1353. 10.1126/science.1167000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Vleugel M., Backer C.B., Hori T., Fukagawa T., Cheeseman I.M., and Lampson M.A.. 2010. Regulated targeting of protein phosphatase 1 to the outer kinetochore by KNL1 opposes Aurora B kinase. J. Cell Biol. 188:809–820. 10.1083/jcb.201001006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Jia L., and Yu H.. 2013. Phospho-H2A and cohesin specify distinct tension-regulated Sgo1 pools at kinetochores and inner centromeres. Curr. Biol. 23:1927–1933. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Qu Q., Warrington R., Rice A., Cheng N., and Yu H.. 2015. Mitotic transcription installs Sgo1 at centromeres to coordinate chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell. 59:426–436. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano E., Gómez R., Gutiérrez-Caballero C., Herrán Y., Sánchez-Martín M., Vázquez-Quiñones L., Hernández T., de Alava E., Cuadrado A., Barbero J.L., et al. . 2008. Shugoshin-2 is essential for the completion of meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice. Genes Dev. 22:2400–2413. 10.1101/gad.475308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M., and Kapoor T.M.. 2011. Constitutive Mad1 targeting to kinetochores uncouples checkpoint signalling from chromosome biorientation. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:475–482. 10.1038/ncb2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows J.C., Shepperd L.A., Vanoosthuyse V., Lancaster T.C., Sochaj A.M., Buttrick G.J., Hardwick K.G., and Millar J.B.. 2011. Spindle checkpoint silencing requires association of PP1 to both Spc7 and kinesin-8 motors. Dev. Cell. 20:739–750. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megraw T.L., Sharkey J.T., and Nowakowski R.S.. 2011. Cdk5rap2 exposes the centrosomal root of microcephaly syndromes. Trends Cell Biol. 21:470–480. 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meppelink A., Kabeche L., Vromans M.J., Compton D.A., and Lens S.M.. 2015. Shugoshin-1 balances Aurora B kinase activity via PP2A to promote chromosome bi-orientation. Cell Reports. 11:508–515. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Barrera M., and Monje-Casas F.. 2014. Increased Aurora B activity causes continuous disruption of kinetochore-microtubule attachments and spindle instability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:E3996–E4005. 10.1073/pnas.1408017111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto S., Senda M., Akai Y., Sato L., Suzuki T., Nagai R., Senda T., and Horikoshi M.. 2007. Relationship between the structure of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT and its histone chaperone activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:4285–4290. 10.1073/pnas.0603762104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata K., Saito S., Okuwaki M., Kawase H., Furuya A., Kusano A., Hanai N., Okuda A., and Kikuchi A.. 1998. Cellular localization and expression of template-activating factor I in different cell types. Exp. Cell Res. 240:274–281. 10.1006/excr.1997.3930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neviani P., and Perrotti D.. 2014. SETting OP449 into the PP2A-activating drug family. Clin. Cancer Res. 20:2026–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth M., Mayer B., Rehm K., Rothweiler U., Heidmann D., Holak T.A., and Stemmann O.. 2011. Shugoshin is a Mad1/Cdc20-like interactor of Mad2. EMBO J. 30:2868–2880. 10.1038/emboj.2011.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi S.T., Wang Z.B., Ouyang Y.C., Zhang Q.H., Hu M.W., Huang X., Ge Z., Guo L., Wang Y.P., Hou Y., et al. . 2013. Overexpression of SETβ, a protein localizing to centromeres, causes precocious separation of chromatids during the first meiosis of mouse oocytes. J. Cell Sci. 126:1595–1603. 10.1242/jcs.116541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattani A., Wolna M., Ploquin M., Helmhart W., Morrone S., Mayer B., Godwin J., Xu W., Stemmann O., Pendas A., and Nasmyth K.. 2013. Sgol2 provides a regulatory platform that coordinates essential cell cycle processes during meiosis I in oocytes. eLife. 2:e01133 10.7554/eLife.01133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel C.G., Katis V.L., Katou Y., Mori S., Itoh T., Helmhart W., Gálová M., Petronczki M., Gregan J., Cetin B., et al. . 2006. Protein phosphatase 2A protects centromeric sister chromatid cohesion during meiosis I. Nature. 441:53–61. 10.1038/nature04664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg J.S., Cross F.R., and Funabiki H.. 2011. KNL1/Spc105 recruits PP1 to silence the spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 21:942–947. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saddoughi S.A., Gencer S., Peterson Y.K., Ward K.E., Mukhopadhyay A., Oaks J., Bielawski J., Szulc Z.M., Thomas R.J., Selvam S.P., et al. . 2013. Sphingosine analogue drug FTY720 targets I2PP2A/SET and mediates lung tumour suppression via activation of PP2A-RIPK1-dependent necroptosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 5:105–121. 10.1002/emmm.201201283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S., Nouno K., Shimizu R., Yamamoto M., and Nagata K.. 2008. Impairment of erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation by a leukemia-associated and t(9;9)-derived fusion gene product, SET/TAF-Iβ-CAN/Nup214. J. Cell. Physiol. 214:322–333. 10.1002/jcp.21199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S., Cigdem S., Okuwaki M., and Nagata K.. 2016. Leukemia-associated Nup214 fusion proteins disturb the XPO1-mediated nuclear-cytoplasmic transport pathway and thereby the NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 36:1820–1835. 10.1128/MCB.00158-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S., Kovacikova I., and Gregan J.. 2013. Chromosome segregation: Disarming the protector. Curr. Biol. 23:R236–R239. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama K., Sugiura K., Hara T., Sugimoto K., Shima H., Honda K., Furukawa K., Yamashita S., and Urano T.. 2002. Aurora-B associated protein phosphatases as negative regulators of kinase activation. Oncogene. 21:3103–3111. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suijkerbuijk S.J., Vleugel M., Teixeira A., and Kops G.J.. 2012. Integration of kinase and phosphatase activities by BUBR1 ensures formation of stable kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Dev. Cell. 23:745–755. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Gao J., Dong X., Liu M., Li D., Shi X., Dong J.-T., Lu X., Liu C., and Zhou J.. 2008. EB1 promotes Aurora-B kinase activity through blocking its inactivation by protein phosphatase 2A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:7153–7158. 10.1073/pnas.0710018105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T.U. 2010. Kinetochore-microtubule interactions: Steps towards bi-orientation. EMBO J. 29:4070–4082. 10.1038/emboj.2010.294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Shu H., Qi W., Mahmood N.A., Mumby M.C., and Yu H.. 2006. PP2A is required for centromeric localization of Sgo1 and proper chromosome segregation. Dev. Cell. 10:575–585. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanno Y., Kitajima T.S., Honda T., Ando Y., Ishiguro K., and Watanabe Y.. 2010. Phosphorylation of mammalian Sgo2 by Aurora B recruits PP2A and MCAK to centromeres. Genes Dev. 24:2169–2179. 10.1101/gad.1945310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuka M., Katayama H., Ota T., Tanaka T., Odashima S., Suzuki F., and Terada Y.. 1998. Multinuclearity and increased ploidy caused by overexpression of the aurora- and Ipl1-like midbody-associated protein mitotic kinase in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 58:4811–4816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada Y., Tatsuka M., Suzuki F., Yasuda Y., Fujita S., and Otsu M.. 1998. AIM-1: A mammalian midbody-associated protein required for cytokinesis. EMBO J. 17:667–676. 10.1093/emboj/17.3.667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S.L., and Compton D.A.. 2008. Examining the link between chromosomal instability and aneuploidy in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 180:665–672. 10.1083/jcb.200712029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara T., Tanno Y., and Watanabe Y.. 2010. Phosphorylation of the CPC by Cdk1 promotes chromosome bi-orientation. Nature. 467:719–723. 10.1038/nature09390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallardi G., Allan L.A., Crozier L., and Saurin A.T.. 2019. Division of labour between PP2A-B56 isoforms at the centromere and kinetochore. eLife. 8:e42619 10.7554/eLife.42619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lindern M., Fornerod M., van Baal S., Jaegle M., de Wit T., Buijs A., and Grosveld G.. 1992. The translocation (6;9), associated with a specific subtype of acute myeloid leukemia, results in the fusion of two genes, dek and can, and the expression of a chimeric, leukemia-specific dek-can mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:1687–1697. 10.1128/MCB.12.4.1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak C.E., Cai S., and Khodjakov A.. 2010. Mechanisms of chromosome behaviour during mitosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:91–102. 10.1038/nrm2832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welburn J.P., Vleugel M., Liu D., Yates J.R. III, Lampson M.A., Fukagawa T., and Cheeseman I.M.. 2010. Aurora B phosphorylates spatially distinct targets to differentially regulate the kinetochore-microtubule interface. Mol. Cell. 38:383–392. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi Y., Sakuno T., Shimura M., and Watanabe Y.. 2008. Heterochromatin links to centromeric protection by recruiting shugoshin. Nature. 455:251–255. 10.1038/nature07217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui Y., Urano T., Kawajiri A., Nagata K., Tatsuka M., Saya H., Furukawa K., Takahashi T., Izawa I., and Inagaki M.. 2004. Autophosphorylation of a newly identified site of Aurora-B is indispensable for cytokinesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:12997–13003. 10.1074/jbc.M311128200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaytsev A.V., Segura-Peña D., Godzi M., Calderon A., Ballister E.R., Stamatov R., Mayo A.M., Peterson L., Black B.E., Ataullakhanov F.I., et al. . 2016. Bistability of a coupled Aurora B kinase-phosphatase system in cell division. eLife. 5:e10644 10.7554/eLife.10644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.