Abstract

Enteric fermentation in ruminants is the single largest anthropogenic source of agricultural methane and has a significant role in global warming. Consequently, innovative solutions to reduce methane emissions from livestock farming are required to ensure future sustainable food production. One possible approach is the use of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), Gram positive bacteria that produce lactic acid as a major end product of carbohydrate fermentation. LAB are natural inhabitants of the intestinal tract of mammals and are among the most important groups of microorganisms used in food fermentations. LAB can be readily isolated from ruminant animals and are currently used on-farm as direct-fed microbials (DFMs) and as silage inoculants. While it has been proposed that LAB can be used to reduce methane production in ruminant livestock, so far research has been limited, and convincing animal data to support the concept are lacking. This review has critically evaluated the current literature and provided a comprehensive analysis and summary of the potential use and mechanisms of LAB as a methane mitigation strategy. It is clear that although there are some promising results, more research is needed to identify whether the use of LAB can be an effective methane mitigation option for ruminant livestock.

Keywords: lactic acid bacteria, methane, methanogens, bacteriocins, direct-fed microbials, silage inoculants, mitigation

Introduction

While ruminant animals play an important role in sustainable agricultural systems (Eisler et al., 2014) they are also an important source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Reisinger and Clark, 2018). Regardless of the ruminant species, the largest source of GHG emissions from ruminant production is methane (CH4), with more than 90 percent of emissions originating from enteric fermentation (Opio et al., 2013). Enteric fermentation is a digestive process by which a community of microbes present in the forestomach of ruminants (the reticulo-rumen) break down plant material into nutrients that can be used by the animal for the production of high-value proteins that include milk, meat and leather products. Hydrogen (H2) and methyl-containing compounds generated as fermentation end products of this process are used by different groups of rumen methanogenic archaea to form CH4, which is belched and exhaled from the lungs via respiration from the animal and released to the atmosphere. In the coming decades, livestock farmers will face numerous challenges and the development of technologies and practices which support efficient sustainable food production while moderating greenhouse gas emissions are urgently required. More than 100 countries have committed to reducing agricultural GHG emissions in the 2015 Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, however, known agricultural practices could deliver just 21–40% of the needed reduction, even if implemented fully at scale (Wollenberg et al., 2016). New technical mitigation options are needed. Reviews of CH4 mitigation strategies consistently discuss the possibility that lactic acid bacteria (LAB) could be used to modulate rumen microbial communities thus providing a practical and effective on-farm approach to reducing CH4 emissions from ruminant livestock (Hristov et al., 2013; Takahashi, 2013; Knapp et al., 2014; Jeyanathan et al., 2014; Varnava et al., 2017). This review examines the possible contribution of LAB in the development of an on-farm CH4 mitigating strategy.

Results and Discussion

General Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria

Lactic acid bacteria are Gram positive, acid tolerant, facultatively anaerobic bacteria that produce lactic acid as a major end-product of carbohydrate fermentation (Stilez and Holzapfel, 1997). Biochemically they include homofermenters that produce primarily lactic acid, and heterofermenters that also give a variety of other fermentation end-products such as acetic acid, ethanol and CO2. LAB have long been used as starter cultures for a wide range of dairy, meat and plant fermentations, and this history of use in human and animal foods has resulted in most LAB having Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) status in the European Union or Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status in the United States. The main LAB genera used as starter cultures are Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, and Pediococcus (Bintsis, 2018) together with some species of Enterococcus and Streptococcus.

In addition to their contribution to the development of food flavor and texture, LAB have an important role in inhibiting the growth of spoilage organisms through the production of inhibitory compounds. These compounds include fermentation products such as organic acids and hydrogen peroxide as well as ribosomally synthesized peptides known as bacteriocins (Cotter et al., 2013). In many cases, the physiological role of bacteriocins is unclear but they are thought to offer the producing organism a competitive advantage, via their ability to inhibit the growth of other microorganisms, particularly in complex microbial communities. Some strains also produce other compounds such as non-ribosomally synthesized peptides which may have additional antimicrobial activity (Mangoni and Shai, 2011).

In recent years much interest has been shown in the use of LAB as probiotic organisms and in their potential contribution to human health and well-being. LAB have also been advocated as probiotics to improve food animal production and as alternatives to antibiotics used as growth promotors (Vieco-Saiz et al., 2019).

LAB and the Rumen

LAB are members of the normal gastrointestinal tract microbiota, however, in ruminants these organisms are generally only prevalent in young animals before the rumen has properly developed (Stewart et al., 1988). LAB are unable to initiate the metabolism of plant structural polysaccharides and are not regarded as major contributors to rumen fermentation. In the Global Rumen Census project (Henderson et al., 2015) which profiled the microbial community of 684 rumen samples collected from a range of ruminant species, only members of the genus Streptococcus were found in a majority of samples (63% prevalence, 0.5% abundance). Nevertheless, LAB can be readily isolated from the rumen, with some species such as Lactobacillus ruminis and Streptococcus equinus (formerly S. bovis) being regarded as true rumen inhabitants while others (Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactococcus lactis) are likely to be transient bacteria that have been introduced with the feed (Stewart, 1992). Several obligately anaerobic rumen bacteria also produce lactate as a fermentation end product and two of these are included in this review. These organisms (Kandleria vitulina and Sharpea azabuensis) are both members of the family Erysipelotrichaceae within the phylum Firmicutes, although Kandleria vitulina was formerly known as Lactobacillus vitulinus (Salvetti et al., 2011). Sharpea and Kandleria are a significant component of the rumen microbiome in low CH4 yield animals in which rapid heterofermentative growth results in lactate production (Kamke et al., 2016).

Table 1 lists the rumen LAB together with strains of Kandleria and Sharpea that have been genome sequenced along with potential antimicrobial biosynthetic clusters predicted from the genome sequence data. The majority (81%) of genome sequenced strains from rumen members of the Streptococcaceae encode antimicrobial biosynthetic clusters, and previous studies have also reported that rumen streptococci can produce a range of bacteriocins (Iverson and Mills, 1976; Mantovani et al., 2001; Whitford et al., 2001). Conversely, antimicrobial biosynthetic genes have not been identified from the species Kandleria vitulina and Sharpea azabuensis.

TABLE 1.

List of rumen LAB cultures in addition to a further two species of obligately anaerobic rumen bacteria (Kandleria and Sharpea) also known to produce lactate as a fermentation end product.

| Family/Order | Genus/Species | Strain | Culture collection # | Origin | Comments | Predicted antimicrobial biosynthetic clusters | References |

| Enterococcaceae | Enterococcus faecalis | 68A | Sheep rumen/NZ | Hudson et al., 1995 | |||

| Enterococcaceae | Enterococcus gallinarum | SKF1 | Sheep rumen/NZ | Lantipeptide | Morvan and Joblin, 2000 | ||

| Enterococcaceae | Enterococcus mundtii | C2 | Cow rumen/NZ | Bacteriocin | |||

| Enterococcaceae | Enterococcus sp. | KPPR-6 | Cow rumen/NZ | Bacteriocin, NRPS | |||

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Kandleria vitulina | MC3001 | Cow rumen/NZ | Noel, 2013 | |||

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Kandleria vitulina | WCE2011 | Cow rumen/NZ | Noel, 2013 | |||

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Kandleria vitulina | RL2 | DSM 20405 | Calf rumen/UK | Type strain | Bryant et al., 1958; Sharpe et al., 1973 | |

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Kandleria vitulina | S3b | Sheep rumen/NZ | Attwood et al., 1998 | |||

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Kandleria vitulina | WCC7 | Cow rumen/NZ | ||||

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Kandleria vitulina | KH4T7 | Cow rumen/NZ | ||||

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Sharpea azabuensis | RL1 | DSM 20406 | Calf rumen/USA | Bryant et al., 1958 | ||

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Sharpea azabuensis | KH1P5 | Cow rumen/NZ | ||||

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Sharpea azabuensis | KH2P10 | Cow rumen/NZ | ||||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus brevis | AG48 | Sheep rumen/NZ | Lantipeptide | Hudson et al., 2000 | ||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus mucosae | AGR63 | Cow rumen/NZ | Morvan and Joblin, 2000 | |||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus mucosae | WCC8 | Cow rumen/NZ | ||||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus mucosae | KHPC15 | Cow rumen/NZ | ||||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus mucosae | KHPX11 | Cow rumen/NZ | ||||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus plantarum | AG30 | Sheep rumen/NZ | Hudson et al., 2000 | |||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus ruminis | RF1 | DSM 20403 | Cow rumen/UK | Type strain | Bacteriocin | Sharpe et al., 1973 |

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus ruminis | WC1T17 | Cow rumen/NZ | ||||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus ruminis | RF3 | ATCC 27782 | Cow rumen/UK | Bacteriocin | Forde et al., 2011 | |

| Lactobacillaceae | Pediococcus acidilactici | AGR20 | Sheep rumen/NZ | Morvan and Joblin, 2000 | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris | DPC6856 | Cow rumen/Ireland | Bacteriocin | Cavanagh et al., 2015 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis | 511 | Cow rumen/NZ | Lantipeptide (nisin) | Kelly et al., 2010 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | B315 | Sheep rumen/NZ | Lantipeptide X2 | Reilly et al., 2002 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | SN033 | Deer rumen/NZ | Lantipeptide X3 | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | AG46 | Sheep rumen/NZ | Hudson et al., 2000 | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | 2B | Sheep rumen/UK | Oxford, 1958 | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | JB1 | Cow rumen/USA | Bacteriocin | Russell and Baldwin, 1978 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | GA-1 | Cow rumen/NZ | Lantipeptide X2 | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | pGA-7 | Cow rumen/NZ | Bacteriocin, Lantipeptide | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | pR-5 | Cow rumen/NZ | Lantipeptide | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | ES1 | Sheep rumen/UK | Lantipeptide | Marounck and Wallace, 1984 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | C277 | Sheep rumen/UK | Bacteriocin, Lantipeptide | Wallace and Brammall, 1985 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | H24 | Calf rumen/USA | Lantipeptide | Boyer, 1969 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | Sb04 | Cow rumen/Australia | Bacteriocin | Klieve et al., 1999 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | Sb05 | Cow rumen/Australia | Bacteriocin | Klieve et al., 1999 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | Sb10 | Cow rumen/Australia | Bacteriocin, NRPS | Klieve et al., 1999 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | Sb13 | Cow rumen/Australia | Lantipeptide | Klieve et al., 1999 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | Sb17 | Cow rumen/Australia | Bacteriocin | Klieve et al., 1999 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | Sb18 | Cow rumen/Australia | Klieve et al., 1999 | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | Sb20 | Cow rumen/Australia | Bacteriocin | Klieve et al., 1999 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | YE01 | Goat rumen/Australia | Klieve et al., 1999 | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | Sb09 | Goat rumen/Australia | Bacteriocin | Klieve et al., 1999 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | SI | Sheep rumen/Australia | Klieve et al., 1999 | |||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | AR3 | Sheep rumen/Australia | Bacteriocin, Lantipeptide | Klieve et al., 1989 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus equinus | HC5 | Cow rumen/USA | Lantipeptide | Azevedo et al., 2015 | ||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus gallolyticus | TPC2.3 | LMG 15572 | Goat rumen/Australia | Bacteriocin | Brooker et al., 1994; Sly et al., 1997 | |

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus henryi | A-4 | Cow rumen/NZ | Lantipeptide, Thiopeptide | |||

All strains were sequenced as part of the Hungate1000 project (Seshadri et al., 2018) with the exceptions of L. ruminis RF3, L. lactis subsp. cremoris DPC68656 and S. equinus HC5.

How Are LAB Used in Ruminant Agriculture?

On-farm, LAB are used as direct-fed microbials (DFMs), probiotics and as silage inoculants. The terms DFM and probiotic are used interchangeably in animal nutrition and refer to any type of live microbe-based feed additive. Although the products have different purposes, there is considerable overlap in the bacterial species used.

The efficacy of DFMs containing LAB has been studied mostly in pre-ruminants where their reported benefits include a reduction in the incidence of diarrhea, a decrease in fecal shedding of coliforms, promotion of ruminal development, improved feed efficiency, increased body weight gain, and reduction in morbidity (Krehbiel et al., 2003). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of LAB supplementation in young calves has shown that LAB can exert a protective effect and reduce the incidence of diarrhea (Signorini et al., 2012) and can increase body weight gain and improve feed efficiency (Frizzo et al., 2011). The meta-analysis further revealed that LAB can induce further beneficial effects if administered with whole milk and as a single strain inoculum. The use of DFM supplementation in young ruminants is expanding as farmers look to use natural alternatives to antibiotics to help improve calf health and promote growth.

In the adult ruminant, there is limited research available on the efficacy of LAB DFMs. Their use is targeted at improving the health and performance of animals (Table 2). With regard to health, a meta-analysis of trials evaluating the use of DFMs (predominantly Lactobacillus) to reduce the prevalence of Escherichia coli O157 fecal shedding in beef cattle has shown LAB supplementation to be efficacious (Wisener et al., 2015). Administration of Lactococcus lactis has been shown to be as effective as common antibiotics in the treatment of bovine mastitis (Klostermann et al., 2008). LAB DFMs have also been shown to minimize the risk of ruminal acidosis in some instances (Ghorbani et al., 2002; Lettat et al., 2012). A recent review by Rainard and Foucras (2018) appraised the use of probiotics for mastitis control. The authors concluded that based on the lack of scientific data the use of probiotics to prevent or treat mastitis is not currently recommended. However, use of teat apex probiotics deserves further research. The results from a small number of trials using only LAB supplementation treatment groups to enhance animal performance are mixed (Table 2). Studies where beneficial effects have been reported include an increase in milk yield, change in milk fat composition, improved feed efficiency, and increased daily weight gain but equally there have been studies where no change has been reported (see Table 2). Although responses to DFMs have been positive in some experiments, the basic mechanisms underlying these beneficial effects are not well defined or clearly understood.

TABLE 2.

Animal trials which studied the effect of DFM supplementation containing LAB only on ruminant performance and health.

| Target | Genus | Sector | Animal | N | Treatment/Dose/Strain | Duration of trial | Effect | References Year |

| Performance | Lactobacillus plantarum Lactobacillus casei | Dairy | Holstein cows | 20 | Treatments: (1) Control (2) 1.3 × 109 cfu/g Lactobacillus plantarum P-8 Lactobacillus casei Zhang | 30 days | LAB treatment increased milk produced and certain milk functional components (IgG, lactoferrin, lysozyme, lactoperoxidase) | Xu et al., 2017 |

| Health | Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Pedioccocus acidilactici, Lactobacillus reuteri | Dairy | Holstein cows | 20 | Treatments given intravaginally: (1) L. rhamnosus CECT 278, P. acidilactici CECT 5915, and L. reuteri DSM 20016, with a final cell count of 4.5 × 10 10cdu/dose and a relationship among the 3 probiotics of 12:12:1, respectively; (2) control. | 3 weeks | Vaginal application of LAB maybe capable of modulating the pathogenic environment in the vaginal tract. | Genís et al., 2017 |

| Performance | Propionibacterium Lactobacillus plantarum Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Dairy | Holstein cows | 8 | Treatments: (1) lactose (control); (2) 1010 cfu/d Propionibacterium P63; (3) 1010 cfu/d of both Propionibacterium P63 and Lactobacillus plantarum 115; (4) 1010 cfu/d of both Propionibacterium P63 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus 32 | 4 weeks | Some effects on CH4 production, ruminal PH and milk FA profile but results depended on DFM strain and diet. | Philippeau et al., 2017 |

| Performance | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei Bifidobacterium thermophilum Enterococcus | Dairy | Ewes | 16 | Treatments: (1) control; (2) Lactobacillus acidophilus (2⋅5 × 107 CFU/g), Lactobacillus casei (2⋅5 × 107 CFU/g), Bifidobacterium thermophilum (2⋅5 × 107 CFU/g), and Enterococcus faecium (2⋅5 × 107 CFU/g | 10 weeks | Supplementing ewes with DFM products has very minor effects on milk fatty acid profiles | Payandeh et al., 2017 |

| Health | Lactobacillus sakei Pediococcus acidilactici | Dairy | Holstein cows | 100 | Treatments given intravaginally: (1 and 2) L. sakei FUA3089, P. acidilactici FUA3138, and P. acidilactici FUA3140 with a cell count of 108 −109 cfu/dose; (3) control | 10 weeks | LAB treatment lowered the incidence of metritis and total uterine infections. | Deng et al., 2015 |

| Performance | Lactobacillus acidophilus Propionibacterium freudenreichii | Dairy | Holstein cows | 112 | Treatments: (1) control; (2) 1 g/cow per day of 1 × 109 cfu/g Lactobacillus acidophilus NP51 and 2 × 109 cfu/g Propionibacterium freudenreichii NP24 | 10 weeks | Supplementing cows with DFM products did not affect cow performance | Ferraretto and Shaver, 2015 |

| Performance | Propionibacterium acidipropionici | Beef | Heifers | 20 | Treatments: (1) Control; (2) Propionibacterium acidipropionici strain P169; (3) P. acidipropionici strain P5; (4) Propionibacterium jensenii strain P54. Inoculae of each strain (5 × 109 cfu) were administered daily. | 28 days | Total and major volatile fatty acid profiles were similar among all treatments. No effects were observed on dry matter intake and total tract digestibility of nutrients. Total enteric CH4 production (g/day) was not affected. | Vyas et al., 2014 |

| Health | Propionibacterium Lactobacillus plantarum Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Sheep | Texel wethers | 12 | Treatments: (1) control; (2) Propionibacterium P63; (3) L. plantarum strain 115 plus P63 4) L. rhamnosus strain 32 plus P63. Treatment administered at a dose of 1 × 1011 cfu/wether/d. | 24 days | LAB treatments may be effective in stabilizing ruminal pH and therefore preventing SARA risk, but they were not effective against lactic acidosis. | Lettat et al., 2012 |

| Performance | Lactobacillus acidophilus Propionibacterium freudenreichii | Dairy | Holstein | 60 | Treatments: (1) control; (2) 4 × 109 cfu/head Lactobacillus acidophilus NP51 and Propionibacterium freudenreichii NP24 (3) DFM plus glycerol | 10 weeks | LAB treatments improved milk and protein yield, energy corrected milk | Boyd et al., 2011 |

| Health and performance | Lactobacillus plantarum | Dairy | Female goats of Damascus breed | 24 | Goats were assigned to one of 2 treatments (1) 1012 cfu/day of L. plantarum PCA 236 (2) control | 5 weeks | LAB treatment resulted in a decrease in fecal clostridia populations and a significantly higher content of polyunsaturated fatty acids in milk fat composition | Maragkoudakis et al., 2010 |

| Health | Lactococcus lactis | Dairy | Holstein Friesian cows | 6 | 5-ml suspension (containing 108 cfu L. lactis DPC 3147) was infused into cow teat | 400 h | Infusion with a live culture of a L. lactis lead to a rapid and considerable innate immune response. | Beecher et al., 2009 |

| Performance | Propionibacterium | Dairy | Holstein cows | 50 | Treatments: (1) control; (2) Propionibacterium P169 at 6 × 1011 cfu per 25g of material | 17 weeks | DFM supplementation did not increase milk production nor change milk composition but did increase feed efficiency | Weiss et al., 2008 |

| Health | Lactococcus lactis | Dairy | Holstein-Friesian and New Zealand Friesians, Norwegian Reds, Normandes and Montbelliards. | Trial 1: 11; Trial 2:25 | The injected suspension contained approximately 9. 1 ± 0. 5 10 cfu/ml of L. lactis DPC3147 | Trial 1: 2 weeks; Trial 2: 8 months | Of the 25 cases treated with the culture, 15 did not exhibit clinical signs of the disease following treatment. The results of these trials suggest that live culture treatment with L. lactis DPC3147 may be as efficacious as common antibiotic treatments in some instances. | Klostermann et al., 2008 |

| Performance | Lactobacillus acidophilus Propionibacteria freudenreichii | Dairy | Holstein cows | 57 | Cows were randomly assigned to one of three diets. (1) 1 × 109 cfu/d L. acidophilus strain LA747 and 2 × 102 cfu/day P. freudenreichii strain PF2f. (2) 1 × 109 cfu/day L. acidophilus strain LA747, 2 × 109 cfu/day P. freudenreichii strain PF2f. (3) lactose (control) | 28 days | Supplementing cows with DFM products did not affect cow performance, digestibility or rumen fermentation. | Raeth-Knight et al., 2007 |

| Performance | Propionibacterium | Dairy | Holstein | 44 | Cows were randomly assigned to one of 3 treatments (1) control (2) 6 × 1010 cfu/cow of Propionibacterium P169 (3) 6 × 1011 cfu/cow of P169 | 30 weeks | DFM supplementation enhanced ruminal digestion of forage and early lactation cows receiving supplementation produced more milk but experienced a lower, but not depressed, fat percentage. | Stein et al., 2006 |

| Performance | Lactobacillus acidophilus Propionibacterium freudenreichii | Beef | Steer cattle | Trial 1: 240 Trial 2: 660 | Trial 1: four treatments (1) control, (2) 1 × 109 cfu of L. acidophilus NP51 plus 1 × 106 cfu of L. acidophilus NP45 plus 1 × 109 cfu of P. freudenreichii NP24 per animal daily, (3) 1 × 109 cfu of L. acidophilus NP51 plus 1 × 109 cfu of P. freudenreichii NP24 per animal daily (4) 1 × 106 cfu of L. acidophilus NP51 plus 1 × 106 cfu L. acidophilus NP45 plus 1 × 109 cfu of P. freudenreichii NP24 per animal daily. Trial 2: three treatments (1) control (2) 5 × 106 cfu of L. acidophilus NP51 plus 5 × 106 cfu of L. acidophilus strain NP45 plus 1 × 109 cfu of P. freudenreichii NP24 per animal daily (3) 1 × 109 cfu of L. acidophilus NP51 plus 5 × 106 cfu L. acidophilus NP45 plus 1 × 109 cfu of P. freudenreichii NP24 per animal daily. | 140 days | Overall, DFM supplementation did not greatly affect feedlot performance and carcass characteristics | Elam et al., 2003 |

| Health | Propionibacterium Enterococcus faecium | Beef | Steer cattle | 6 | Treatments: (1) control, (2) Propionibacterium P15,(3) Propionibacterium P15 plus Enterococcus faecium EF212. Dose of 1 × 109 cfu/g | 20 days | DFM supplementation did not affect blood pH and blood glucose, however, steers fed the treatment had lower concentrations of blood CO2 than control steers, which is consistent with a reduced risk of metabolic acidosis. | Ghorbani et al., 2002 |

| Performance | Lactobacillus acidophilus Propionibacterium freudenreichii | Beef | Heifers | 450 | Treatments: (1) control; (2) 5 × 108 cfu/head/d L. acidophilus BG2FO4; (3) 1 × 109 cfu/head/d P. freudenreichii P-63; (4) 5 × 108 cfu/head/d L. acidophilus BG2FO4 and 1 × 109 cfu/head/d freudenreichii P-63; (5) 5 × 108 cfu/head/d L. acidophilus BG2FO4 and 1 × 109 cfu/head/d P. freudenreichii P-63 | 126 days | Combined DFM supplementation resulted in significant improvements in daily gain and feed efficiency | Huck et al., 2000 |

Trials related to the use of LAB supplementation to reduce shedding of E. coli O157:H7 in beef cattle are not listed but can be found in the meta-analysis performed by Wisener et al. (2015).

LAB are the dominant silage inoculant in many parts of the world. LAB are used not only for their convenience and safety, but also because they are effective in controlling microbial events during silage fermentation (Muck et al., 2018). In the ensiling process, a succession of LAB ferment the available soluble sugars in cut plant material to produce organic acids, including lactic acid. As a result, the pH drops, preventing further microbial degradation of the plant material and preserving it as silage. The efficacy of adding LAB inoculants in enhancing the natural silage preservation process is well established. In addition, silage inoculants containing homofermentative LAB have not only improved silage quality and reduced fermentation losses but have also improved animal performance by increasing milk yield, daily gain and feed efficiency (Kung et al., 1993; Weinberg and Muck, 1996, 2013; Kung and Muck, 1997; Muck et al., 2018). The mechanism(s) behind the additional benefits in animal performance from feeding inoculated silage are not understood.

LAB DFMs and silage inoculants are microbial based technologies which are widely accepted and actively used in modern farming systems today. If LAB can be found to reduce ruminant CH4 production effectively then both DFMs and inoculants provide a practical and useful mitigation option on-farm.

Methanogens and the Rumen

Rumen methanogenic archaea are much less diverse than rumen bacteria (Henderson et al., 2015), and members of two clades of the genus Methanobrevibacter (referred to as M. gottschalkii and M. ruminantium) make up ∼75% of the archaeal community (Janssen and Kirs, 2008; Henderson et al., 2015). Cultivated members of both of these methanogen clades are hydrogenotrophic and use H2 and CO2 for CH4 formation. Their cell walls contain pseudomurein and have similarities to those found in Gram positive bacteria which may be relevant to their sensitivity to antimicrobial agents (Varnava et al., 2017). Other significant members of the methanogen community in the rumen are methylotrophs, producing CH4 from methyl-containing substrates, particularly methylamines and methanol. These include strains of the genus Methanosphaera and members of the family Methanomassiliicoccaceae. The former have pseudomurein-containing cell walls, while the cell envelope surrounding the Methanomassiliicoccaceae has not been characterized. The ability of rumen bacteria to produce the H2 or methyl-containing substrates required for methanogenesis has been determined from culture studies, or is able to be inferred from genome sequences, but it is not yet known which bacteria are the most important contributors in the rumen.

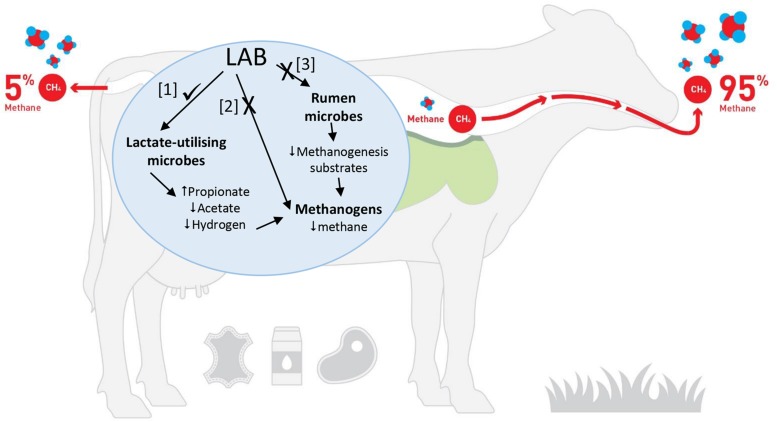

How could LAB reduce ruminant CH4 production? It is hypothesized that LAB could influence ruminal methanogenesis in three possible ways (Figure 1): (1) use of LAB or their metabolites to shift the rumen fermentation so that there is a corresponding decrease in CH4 production, (2) use of LAB or their metabolites to directly inhibit rumen methanogens and (3) use of LAB or their metabolites to inhibit specific rumen bacteria that produce H2 or methyl-containing compounds that are the substrates for methanogenesis.

FIGURE 1.

Potential pathways that could be modulated by LAB to decrease CH4 production [Adapted from FAO (2019). Image is being used with the permission of the copyright holder, New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (www.nzagrc.org.nz)].

How Have LAB Been Shown to Affect Ruminant CH4 Production?

The idea that LAB can be used to reduce CH4 production in ruminant livestock is not new. Reviews of CH4 mitigation strategies consistently refer to this possibility (Hristov et al., 2013; Takahashi, 2013; Jeyanathan et al., 2014; Knapp et al., 2014; Varnava et al., 2017). However, research on the topic has been limited and convincing data from animal trials to support this concept are lacking. Jeyanathan et al. (2016) screened 45 bacteria, including strains of LAB, bifidobacteria and propionibacteria, in 24h rumen in vitro batch incubations for their ability to reduce methanogenesis. Three strains were selected for in vivo trials in sheep (n = 12), and one strain (Lactobacillus pentosus D31) showed a 13% reduction in CH4 production (g CH4/kg/DMI) over 4 weeks when dosed at 6 × 1010 cfu/animal/day. The mechanism of action was not determined in this study, but the ability of introduced bacterial strains to persist in the rumen environment was highlighted as an important factor. Subsequent work by Jeyanathan et al. (2019) using the same strains has shown no ability to reduce CH4 emissions in dairy cows. A further two studies which examined LAB supplementation on CH4 production have had mixed results. Mwenya et al. (2004) assessed the effect of feeding Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides to sheep (n = 4). Supplementation with this strain was found to increase CH4 production (g CH4/kg/DMI) in vivo. The authors did not offer any discussion as to how a LAB strain could increase CH4 production in vivo. Astuti et al. (2018) evaluated 14 strains of L. plantarum in rumen in vitro experiments and identified strain U32 which had the lowest CH4 production value when compared to the other LAB treatment groups. The authors hypothesized the addition of LAB may have stimulated the growth of lactic utilizing bacteria leading to increased production of propionic acid and a subsequent decrease in the hydrogen availability for methane production (Astuti et al., 2018).

Research conducted on bacteriocins and their ability to reduce ruminal CH4 production has been minimal. The few bacteriocins and preparations from bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria that have been examined have displayed promising results both in vitro and in vivo. Callaway et al. (1997) tested the effect of the Lactococcus lactis bacteriocin nisin on rumen fermentation in vitro and reported a 36% reduction in CH4 production. However, later work has shown nisin to be susceptible to rumen proteases limiting its potential efficacy in vivo (Russell and Mantovani, 2002). One in vivo trial has, however, reported a 10% decrease in CH4 emissions (g/kg DMI) in sheep (n = 4) fed this bacteriocin (Santoso et al., 2004). The trial was conducted for 15 days and the authors surmised that the reduction in CH4 was due to the inhibition of growth of the methanogenic microbes. Nollet et al. (1998) examined the addition of the cell-free supernatant of Lactobacillus plantarum 80 (LP80) to ruminal samples in vitro and noted an 18% decrease in CH4 production and a 30.6% reduction in CH4 when the supernatant was combined with an acetogenic culture, Peptostreptococcus productus ATCC 35244. The effect of the LP80 supernatant in combination with P. productus was also studied in vivo using two rams and it was concluded that inhibition of methanogenesis (80% decrease; mmol/6 h) occurred during the first 3 days but the effect did not persist. Compounds (PRA1) produced by L. plantarum TUA1490L were tested in vitro and found to decrease methanogenesis by 90% (Asa et al., 2010). Further work with PRA1 confirmed its ability to maintain an antimicrobial effect even after incubation with proteases but the hypothesis that the inhibition mechanism of PRA1 may relate to the production of hydrogen peroxide has not been proven (Takahashi, 2013). Bovicin HC5, a bacteriocin produced by Streptococcus equinus HC5, inhibited CH4 production by 53% in vitro (Lee et al., 2002), while more recently the bacteriocin pediocin produced by Pediococcus pentosaceus 34 was shown to reduce CH4 production in vitro by 49% (Renuka et al., 2013). The possibility of using bacteriocins from rumen streptococci for CH4 mitigation has recently been reviewed (Garsa et al., 2019). Currently, it is not clear whether the bacteriocins affect the methanogens themselves, or whether they affect the other rumen microbes that produce substrates necessary for methanogenesis. The only evidence that bacteriocins affect methanogens directly is a single article (Hammes et al., 1979) in which nisin was shown to inhibit a non-rumen methanogen, Methanobacterium, using an agar diffusion assay to determine the inhibitory effect. Recently, Shen et al. (2017) used in vitro assays and 16S rRNA gene analysis to assess the effect nisin has on rumen microbial communities and fermentation characteristics. Results demonstrate that nisin treatments can reduce populations of total bacteria, fungi and methanogens resulting in a decrease in the ratio of acetate to propionate concentrations. A similar class of compounds (antimicrobial peptides such as human catelicidin) have also been shown to be strongly inhibitory to a range of methanogens (Bang et al., 2012, 2017). There is no standardized approach to screening methanogen cultures for their susceptibility to bacteriocins, however, the method developed to facilitate screening of small molecule inhibitors (Weimar et al., 2017) should be useful. This employs the rumen methanogen strain AbM4 (a strain of Methanobrevibacter boviskoreani) which grows without H2 in the presence of ethanol and methanol (Leahy et al., 2013).

Many LAB silage inoculants possess antibacterial and/or antifungal activity and in some cases this activity is imparted into the inoculated silage (Gollop et al., 2005). The inhibitory activity has been shown to inhibit detrimental micro-organisms in silage (Flythe and Russell, 2004; Marciňáková et al., 2008; Amado et al., 2012) and has been postulated to do the same in the rumen, but the role of specific silage inoculants in CH4 mitigation has received little attention. Thus far, research has demonstrated that LAB included in freeze-dried silage inoculants can survive in rumen fluid (Weinberg et al., 2003) and that LAB survive passage from silage into rumen fluid in vitro (Weinberg et al., 2004). Several studies have demonstrated that in vitro rumen fermentation can be altered by some LAB strains. Muck et al. (2007) made silages using a range of inoculants and showed in vitro that some of the inoculated silages had reduced gas production compared with the untreated silage suggesting a shift in fermentation had occurred. Cao et al. (2010a) investigated the effect of L. plantarum Chikuso-1 on an ensiled total mixed ration (TMR) and showed CH4 production decreased by 8.6% and propionic acid increased by 4.8% compared with untreated TMR silage. Cao et al. (2011) found similar results with the same inoculant strain in vegetable residue silage with the inoculated silage having higher in vitro dry matter digestibility and lower CH4 production (46.6% reduction). Further work with this LAB strain in vivo showed that the inoculated TMR silage increased digestibility and decreased ruminal CH4 (kg DMI) emissions (24.7%) in sheep (n = 4) compared with a non-inoculated control (Cao et al., 2010b). Although more research is required in this area, the results suggest that some LAB strains are capable of altering ruminal fermentation leading to downstream effects such as reduced CH4 production.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Literature on the use of LAB to reduce CH4 production in ruminants is limited. In the small number of studies available, in vitro, LAB can reduce CH4 production effectively. The effect is clearly strain dependent and it is not understood whether the LAB or their metabolites affect the methanogens themselves, or whether they affect the other rumen microbes that produce substrates necessary for methanogenesis. In vivo, the lack of robust animal trials (appropriate animal numbers, relevant treatment groups, trial period, and strain efficacy) investigating LAB supplementation and CH4 mitigation make it impossible at this time to make a comprehensive conclusion. Much more research is needed to understand the mechanisms behind the use of LAB as rumen modifiers. However, if appropriate LAB cultures can be identified, and proven to be effective in vivo then a range of delivery options that are already accepted in the global farming system such as DFMs and silage inoculants are available. This represents an alternative approach to CH4 mitigation research and one that can be used in combination with other mitigation options such as vaccines (Wedlock et al., 2013) and CH4 inhibitors (Dijkstra et al., 2018) which are currently under development. Ruminant production systems with low productivity lose more energy per unit of animal product than those with high productivity. In systems where farm management practices result in an increase in performance per animal (e.g., kg milk solids per cow, kg lamb slaughtered per ewe, kg beef slaughtered per cow), and combined with a reduction in stocking rates, then absolute CH4 emissions can be reduced. LAB supplementation and use of silage inoculants can contribute to these on-farm management options that reduce agricultural GHG emissions through increases in animal productivity and improved health. LAB supplementation could offer a practical, effective and natural approach to reducing CH4 emissions from ruminant livestock and contribute to the on-farm management practices that can be used to reduce CH4 emissions.

Author Contributions

SL, WK, and GA conceived the research. ND, PM, WK, YL, and SL performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. RR, CS, and GA reviewed the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

WK was employed by the company Donvis Ltd. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. METHLAB – Refining direct fed microbials (DFM) and silage inoculants for reduction of CH4 emissions from ruminants has been funded by FACCE ERA-GAS, an EU ERA-NET Cofund program whereby national money is pooled to fund transnational projects, and the European Commission also provides co-funding for the action. FACCE ERA-GAS is the ERA-NET Cofund for Monitoring and Mitigation of Greenhouse Gases from Agri- and Silvi-culture, and comprises funding agencies and project partners from 19 organizations across 13 European countries. Teagasc, the Agriculture and Food Development Authority in Ireland, is the overall coordinator of the ERA-NET. ND is in receipt of Teagasc Walsh Fellowship. The New Zealand contribution to the FACCE ERA-GAS METHLAB project is funded by the New Zealand Government in support of the objectives of the Livestock Research Group of the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases.

References

- Amado I. R., Fuciños C., Fajardo P., Guerra N. P., Pastrana L. (2012). Evaluation of two bacteriocin-producing probiotic lactic acid bacteria as inoculants for controlling Listeria monocytogenes in grass and maize silages. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 175 137–149. 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2012.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asa R., Tanaka A., Uehara A., Shinzato I., Toride Y., Usui N., et al. (2010). Effects of protease-resistent antimicrobial substances produced by lactic acid bacteria on rumen methanogenesis. Asian-Australa. J. Anim. Sci. 23 700–707. 10.5713/ajas.2010.90444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Astuti W. D., Wiryawan K. G., Wina E., Widyastuti Y., Suharti S., Ridwan R. (2018). Effects of selected Lactobacillus plantarum as probiotic on in vitro ruminal fermentation and microbial population. Pak. J. Nutr. 17 131–139. 10.3923/pjn.2018.131.139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood G. T., Klieve A. V., Ouwerkerk D., Patel B. K. C. (1998). Ammonia-hyperproducing bacteria from New Zealand ruminants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 1796–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo A. C., Bento C. B., Ruiz J. C., Queiroz M. V., Mantovani H. C. (2015). Draft genome sequence of Streptococcus equinus (Streptococcus bovis) HC5, a lantibiotic producer from the bovine rumen. Genome Announc. 3:e00085-e15. 10.1128/genomeA.00085-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang C., Schilhabel A., Weidenbach K., Kopp A., Goldmann T., Gutsmann T., et al. (2012). Effects of antimicrobial peptides on methanogenic archaea. Antimicrobial. Agents Chemother. 56 4123–4130. 10.1128/aac.00661-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang C., Vierbuchen T., Gutsmann T., Heine H., Schmitz R. A. (2017). Immunogenic properties of the human gut-associated archaeon Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis and its susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides. PLoS One 12:e0185919. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecher C., Daly M., Berry D. P., Klostermann K., Flynn J., Meaney W., et al. (2009). Administration of a live culture of Lactococcus lactis DPC 3147 into the bovine mammary gland stimulates the local host immune response, particularly IL-1 and IL-8 gene expression. J. Dairy Res. 76 340–348. 10.1017/S0022029909004154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bintsis T. (2018). Lactic acid Bacteria as starter cultures: an update in their metabolism and genetics. AIMS Microbiol. 4 665–684. 10.3934/microbiol.2018.4.665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J., West J. W., Bernard J. K. (2011). Effects of the addition of direct-fed microbials and glycerol to the diet of lactating dairy cows on milk yield and apparent efficiency of yield. J. Dairy Sci. 94 4616–4622. 10.3168/jds.2010-3984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer E. W. (1969). Amylolytic Enzymes and Selected Physiological Properties of Streptococcus bovis and Streptococcus equinus. Ph.D. thesis, Iowa State University: Ames, IA. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker J. D., O’Donovan L. A., Skene I., Clarke K., Blackall L., Muslera P. (1994). Streptococcus caprinus sp. nov., a tannin-resistent ruminal bacterium from feral goats. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 18 313–318. 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1994.tb00877.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant M. P., Small S. N., Bouma C., Robinson I. (1958). Studies on the composition of the ruminal flora and fauna of young calves. J. Dairy Sci. 41 1747–1767. 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(58)91160-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway T. R., Carneiro De Melo A. M. S., Russell J. B. (1997). The effect of nisin and monensin on ruminal fermentations in vitro. Curr. Microbiol. 35 90–96. 10.1007/s002849900218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Cai Y., Takahashi T., Yoshida N., Tohno M., Uegaki R., et al. (2011). Effect of lactic acid bacteria inoculant and beet pulp addition on fermentation characteristics and in vitro ruminal digestion of vegetable residue silage. J. Dairy Sci. 94 3902–3912. 10.3168/jds.2010-3623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Takahashi T., Horiguchi K., Yoshida N. (2010a). Effect of adding lactic acid bacteria and molasses on fermentation quality and in vitro ruminal digestion of total mixed ration silage prepared with whole crop rice. Grassl. Sci. 56 19–25. 10.1111/j.1744-697x.2009.00168.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Takahashi T., Horiguchi K., Yoshida N., Cai Y. (2010b). Methane emissons from sheep fed fermented or non-fermented total mixed ration containing whole-crop rice and rice bran. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 157 72–78. 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2010.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D., Casey A., Altermann E., Cotter P. D., Fitzgerald G. F., McAuliffe O. (2015). Evaluation of Lactococcus lactis isolates from nondairy sources with potential dairy applications reveals extensive phenotype-genotype disparity and implications for a revised species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 3961–3972. 10.1128/AEM.04092-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter D., Ross P., Hill C. (2013). Bacteriocins — a viable alternative to antibiotics? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11 95–102. 10.1038/nrmicro2937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q., Odhiambo J. F., Farooq U., Lam T., Dunn S. M., Ametaj B. N. (2015). Intravaginal lactic acid bacteria modulated local and systemic immune responses and lowered the incidence of uterine infections in periparturient dairy cows. PLoS One 10:e0124167. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra J., Bannink A., France J., Kebreab E., van Gastelen S. (2018). Antimethanogenic effects of 3-nitrooxypropanol depend on supplementation dose, dietary fiber content, and cattle type. J. Dairy Sci. 101 9041–9047. 10.3168/jds.2018-14456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler M. C., Lee M. R., Tarlton J. F., Martin G. B., Beddington J., Dungait J. A., et al. (2014). Agriculture: steps to sustainable livestock. Nature 507 32–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elam N. A., Gleghorn J. F., Rivera J. D., Galyean M. L., Defoor P. J., Brashears M. M., et al. (2003). Effects of live cultures of Lactobacillus acidophilus (strains NP45 and NP51) and Propionibacterium freudenreichii on performance, carcass, and intestinal characteristics, and Escherichia coli strain O157 shedding of finishing beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 81 2686–2698. 10.2527/2003.81112686x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2019). The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture, eds Belanger J., Pilling D. (Rome: FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Assessments; ), 572. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraretto L. F., Shaver R. D. (2015). Effect of direct-fed microbial supplementation on lactation performance and total-tract starch digestibility by midlactation dairy cows. Prof. Anim. Sci. 31 63–67. 10.15232/pas.2014-01369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flythe M. D., Russell J. B. (2004). The effect of pH and a bacteriocin (bovicin HC5) on Clostridium sporogenes MD1, a bacterium that has the ability to degrade amino acids in ensiled plant materials. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47 215–222. 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00259-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde B. M., Neville B. A., O’Donnell M. M., Riboulet-Bisson E., Claesson M. J., Coghlan A., et al. (2011). Genome sequences and comparative genomics of two Lactobacillus ruminis strains from the bovine and human intestinal tracts. Microb. Cell Fact. 10(Suppl. 1):S13. 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frizzo L. S., Soto L. P., Zbrun M. V., Signorini M. L., Bertozzi E., Sequeira G., et al. (2011). Effect of lactic acid bacteria and lactose on growth performance and intestinal microbial balance of artificially reared calves. Livest. Sci. 140 246–252. 10.1016/j.livsci.2011.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garsa A. K., Choudhury P. K., Puniya A. K., Dhewa T., Malik R. K., Tomar S. K. (2019). Bovicins: the bacteriocins of streptococci and their potential in methane mitigation. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 10.1007/s12602-018-9502-z [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genís S., Bach À, Arís A. (2017). Effects of intravaginal lactic acid bacteria on bovine endometrium: implications in uterine health. Vet. Microbiol. 204 174–179. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani G. R., Morgavi D. P., Beauchemin K. A., Leedle J. A. Z. (2002). Effects of bacterial direct-fed microbials on ruminal fermentation, blood variables, and the microbial populations of feedlot cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 80 1977–1985. 10.2527/2002.8071977x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollop N., Zakin V., Weinberg Z. G. (2005). Antibacterial activity of lactic acid bacteria included in inoculants for silage and in silages treated with these inoculants. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98 662–666. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes W. P., Winter J., Kandler O. (1979). The sensitivity of the pseudomurein-containing genus Methanobacterium to inhibitors of murein synthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 123 275–279. 10.1007/bf00406661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson G., Cox F., Ganesh S., Jonker A., Young W. Global Rumen Census Collaborators et al. (2015). Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Sci. Rep. 5:14567. 10.1038/srep14567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov A. N., Oh J., Firkins J. L., Dijkstra J., Kebreab E., Waghorn G., et al. (2013). Special topics–Mitigation of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from animal operations: I. A review of enteric methane mitigation options. J. Anim. Sci. 91 5045–5069. 10.2527/jas.2013-6583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huck G. L., Kreikemeier K. K., Ducharme G. A. (2000). Effects of feeding two microbial additives in sequence on growth performance and carcass characteristics of finishing heifers. Kansas Agric. Exp. Station Res. Rep. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2097/4655 [Google Scholar]

- Hudson J. A., Cai Y., Corner R. J., Morvan B., Joblin K. N. (2000). Identification and enumeration of oleic acid and linoleic acid hydrating bacteria in the rumen of sheep and cows. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88 286–292. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00968.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson J. A., MacKenzie C. A. M., Joblin K. N. (1995). Conversion of oleic acid to 10-hydroxystearic acid by two species of ruminal bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 44 1–6. 10.1007/s002530050511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson W. G., Mills N. F. (1976). Bacteriocins of Streptococcus bovis. Can. J. Microbiol. 22 1040–1047. 10.1139/m76-151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen P. H., Kirs M. (2008). Structure of the archaeal community of the rumen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 3619–3625. 10.1128/aem.02812-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyanathan J., Martin C., Eugène M., Ferlay A., Popova M., Morgavi D. P. (2019). Bacterial direct-fed microbials fail to reduce methane emissions in primiparous lactating dairy cows. J. Ani. Sci Biotech. 10:41. 10.1186/s40104-019-0342-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyanathan J., Martin C., Morgavi D. P. (2014). The use of direct-fed microbials for mitigation of ruminant methane emissions: a review. Animal 8 250–261. 10.1017/S1751731113002085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyanathan J., Martin C., Morgavi D. P. (2016). Screening of bacterial direct-fed microbials for their antimethanogenic potential in vitro and assessment of their effect on ruminal fermentation and microbial profiles in sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 94 739–750. 10.2527/jas2015-9682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamke J., Kittelmann S., Soni P., Li Y., Tavendale M., Ganesh S., et al. (2016). Rumen metagenome and metatranscriptome analyses of low methane yield sheep reveals a Sharpea-enriched microbiome characterised by lactic acid formation and utilisation. Microbiome 4:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly W. J., Ward L. J. H., Leahy S. C. (2010). Chromosomal diversity in Lactococcus lactis and the origin of dairy starter cultures. Genome Biol. Evol. 2 729–744. 10.1093/gbe/evq056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klieve A. V., Heck G. L., Prance M. A., Shu Q. (1999). Genetic homogeneity and phage susceptibility of ruminal strains of Streptococcus bovis isolated in Australia. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 29 108–112. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00596.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klieve A. V., Hudman J. F., Bauchop T. (1989). Inducible bacteriophages from ruminal bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55 1630–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klostermann K., Crispie F., Flynn J., Ross R. P., Hill C., Meaney W. (2008). Intramammary infusion of a live culture of Lactococcus lactis for treatment of bovine mastitis: comparison with antibiotic treatment in field trials. J. Dairy Res. 75 365–373. 10.1017/S0022029908003373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp J. R., Laur G. L., Vadas P. A., Weiss W. P., Tricarico J. M. (2014). Invited review: enteric methane in dairy cattle production: quantifying the opportunities and impact of reducing emissions. J. Dairy Sci. 97 3231–3261. 10.3168/jds.2013-7234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krehbiel C. R., Rust S. R., Zhang G., Gilliland S. E. (2003). Bacterial direct-fed microbials in ruminant diets: performance response and mode of action. J. Anim. Sci. 81 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kung L., Chen J. H., Creck E. M., Knusten K. (1993). Effect of microbial inoculants on the nutritive value of corn silage for lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 76 3763–3770. 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(93)77719-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung L., Muck R. E. (1997). Animal Response to Silage Additives. In: Silage: Field to Feedbunk, NRAES-99. New York, NY: Northeast Regional Agricultural Engineering Service, 200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy S. C., Kelly W. J., Li D., Li Y., Altermann E., Lambie S. C., et al. (2013). The complete genome sequence of Methanobrevibacter sp. ABM4. Stand. Genom. Sci. 8 215–227. 10.4056/sigs.3977691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. S., Hsu J. T., Mantovani H. C., Russell J. B. (2002). The effect of bovicin HC5, a bacteriocin from Streptococcus bovis HC5, on ruminal methane production in vitro. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 217 51–55. 10.1016/S0378-1097(02)01044-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettat A., Nozière P., Silberberg M., Morgavi D. P., Berger C., Martin C. (2012). Rumen microbial and fermentation characteristics are affected differently by bacterial probiotic supplementation during induced lactic and subacute acidosis in sheep. BMC Microbiol. 12:142. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni M., Shai Y. (2011). Short native antimicrobial peptides and engineered ultrashort lipopeptides: similarities and differences in cell specificities and modes of action. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68 2267–2280. 10.1007/s00018-011-0718-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani H. C., Kam D. K., Ha J. K., Russell J. B. (2001). The antibacterial activity and sensitivity of Streptococcus bovis strains isolated from the rumen of cattle. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37 223–229. 10.1016/s0168-6496(01)00166-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maragkoudakis P. A., Mountzouris K. C., Rosu C., Zoumpopoulou G., Papadimitriou K., Dalaka E., et al. (2010). Feed supplementation of Lactobacillus plantarum PCA 236 modulates gut microbiota and milk fatty acid composition in dairy goats–a preliminary study. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 141(Suppl. 1), S109–S116. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciňáková M., Lauková A., Simonová M., Strompfová V., Koréneková B., Nad P. (2008). A new probiotic and bacteriocin-producing strain of Enterococcus faecium EF9296 and its use in grass ensiling. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 53 335–344. 10.17221/348-cjas [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marounck M., Wallace R. J. (1984). Influence of culture Eh on the growth and metabolism of the rumen bacteria Selenomonas ruminantium, Bacteroides amylophilus, Bacteroides succinogenes and Streptococcus bovis in batch culture. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130 223–229. 10.1099/00221287-130-2-223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morvan B., Joblin K. N. (2000). Hydration of oleic acid by Enterococcus gallinarum, Pediococcus acidilactici and Lactobacillus sp. Anaerobe 5 605–611. 10.1006/anae.1999.0306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muck R. E., Filya I., Contreras-Govea F. E. (2007). Inoculant effects on alfalfa silage: In vitro gas and volatile fatty acid production. J. Dairy Sci. 90 5115–5125. 10.3168/jds.2006-878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muck R. E., Nadeau E. M. G., McAllister T. A., Contreras-Govea F. E., Santos M. C., Kung L. (2018). Silage review: recent advances and future uses of silage additives. J. Dairy Sci. 101 3980–4000. 10.3168/jds.2017-13839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwenya B., Santoso B., Sar C., Gamo Y., Kobayashi T., Arai I., et al. (2004). Effects of including β1-4 galacto-oligosaccharides, lactic acid bacteria or yeast culture on methanogenesis as well as energy and nitrogen metabolism in sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 115 313–326. 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2004.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noel S. (2013). Cultivation and Community Composition Analysis of Plant-adherent Rumen Bacteria. Ph.D. thesis, Massey University: Palmerston North. [Google Scholar]

- Nollet L., Mbanzamihigo L., Demeyer D., Verstraete W. (1998). Effect of the addition of Peptostreptococcus productus ATCC 35244 on reductive acetogenesis in the ruminal ecosystem after inhibition of methanogenesis by cell-free supernatant of Lactobacillus plantarum 80. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 71 49–66. 10.1016/s0377-8401(97)00135-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Opio C., Gerber P., Mottet A., Falcucci A., Tempio G., MacLeod M., et al. (2013). Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Ruminant Supply Chains – A Global Life Cycle Assessment. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). [Google Scholar]

- Oxford A. E. (1958). The nutritional requirements of rumen strains of Streptococcus bovis considered in relation to dextran synthesis from sucrose. J. Gen. Microbiol. 19 617–623. 10.1099/00221287-19-3-617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payandeh S., Kafilzadeh F., Juárez M., De La Fuente M. A., Ghadimi D., Martínez Marín A. L. (2017). Probiotic supplementation effects on milk fatty acid profile in ewes. J. Dairy Res. 84 128–131. 10.1017/S0022029917000115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippeau C., Lettat A., Martin C., Silberberg M., Morgavi D. P., Ferlay A., et al. (2017). Effects of bacterial direct-fed microbials on ruminal characteristics, methane emission, and milk fatty acid composition in cows fed high- or low-starch diets. J. Dairy Sci. 100 2637–2650. 10.3168/jds.2016-11663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeth-Knight M. L., Linn J. G., Jung H. G. (2007). Effect of direct-fed microbials on performance, diet digestibility, and rumen characteristics of Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 90 1802–1809. 10.3168/jds.2006-643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainard P., Foucras G. (2018). A critical appraisal of probiotics for mastitis control. Front. Vet. Sci. 5:251. 10.3389/fvets.2018.00251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly K., Carruthers V. R., Attwood G. T. (2002). Design and use of 16S ribosomal DNA-directed primers in competitive PCRs to enumerate proteolytic bacteria in the rumen. Microb. Ecol. 43 259–270. 10.1007/s00248-001-1052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger A., Clark H. (2018). How much do direct livestock emissions actually contribute to global warming? Glob. Change Biol. 24 1749–1761. 10.1111/gcb.13975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renuka, Puniya M., Sharma A., Malik R., Upadhyay R. C., Puniya A. K. (2013). Influence of pediocin and enterocin on in-vitro methane, gas production and digestibility. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. B., Baldwin R. L. (1978). Substrate preferences in rumen bacteria: evidence of catabolite regulatory mechanisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 36 319–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. B., Mantovani H. C. (2002). The bacteriocins of ruminal bacteria and their potential as an alternative to antibiotics. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4 347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvetti E., Felis G. E., Dellaglio F., Castioni A., Torriani S., Lawson P. A. (2011). Reclassification of Lactobacillus catenaformis (Eggerth 1935) Moore and Holdeman 1970 and Lactobacillus vitulinus Sharpe et al., 1973 as Eggerthia catenaformis gen. nov., comb. nov. and Kandleria vitulina gen. nov., comb. nov., respectively. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61 2520–2524. 10.1099/ijs.0.029231-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoso B., Mwenya B., Sar C., Gamo Y., Kobayashi T., Morikawa R., et al. (2004). Effects of supplementing galacto-oligosaccharides, Yucca schidigera or nisin on ruminal methanogenesis, nitrogen and energy metabolism in sheep. Livest. Prod. Sci. 91 209–217. 10.1016/j.livprodsci.2004.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri R., Leahy S. C., Attwood G. T., Teh K. H., Lambie S. C., Cookson A. L., et al. (2018). Cultivation and sequencing of rumen microbiome members from the Hungate1000 Collection. Nat. Biotechnol. 36 359–367. 10.1038/nbt.4110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe M. E., Latham M. J., Garvie E. I., Zirngibl J., Kandler O. (1973). Two new species of Lactobacillus isolated from the bovine rumen, Lactobacillus ruminis sp. nov. and Lactobacillus vitulinus sp. nov. J. Gen. Microbiol. 77 37–49. 10.1099/00221287-77-1-37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Liu Z., Yu Z., Zhu W. (2017). Monensin and nisin affect rumen fermentation and microbiota differently in vitro. Front. Microbiol. 8:111. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorini M. L., Soto L. P., Zbrun M. V., Sequeira G. J., Rosmini M. R., Frizzo L. S. (2012). Impact of probiotic administration on the health and fecal microbiota of young calves: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of lactic acid bacteria. Res. Vet. Sci. 93 250–258. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sly L. I., Cahill M. M., Osawa R., Fujisawa T. (1997). The tannin-degrading species Streptococcus gallolyticus and Streptococcus caprinus are subjective synonyms. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47 893–894. 10.1099/00207713-47-3-893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D. R., Allen D. T., Perry E. B., Bruner J. C., Gates K. W., Rehberger T. G., et al. (2006). Effects of feeding propionibacteria to dairy cows on milk yield, milk components, and reproduction. J. Dairy Sci. 89 111–125. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72074-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. S. (1992). “Lactic acid bacteria in the rumen,” in The Lactic Acid Bacteria, ed. Wood B. J. B. (Boston, MA: Springer; ), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. S., Fonty G., Gouet P. (1988). The establishment of rumen microbial communities. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 21 69–97. 10.1016/0377-8401(88)90093-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stilez M. E., Holzapfel W. (1997). Lactic acid bacteria of foods and their current taxonomy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 36 1–29. 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01233-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi J. (2013). “Lactic acid bacteria and mitigation of GHG emission from ruminant livestock,” in Lactic Acid Bacteria - R & D for Food, Health and Livestock Purposes, ed. Kongo M. (London: IntechOpen; ). [Google Scholar]

- Varnava K. G., Ronimus R. S., Sarojini V. (2017). A review on comparative mechanistic studies of antimicrobial peptides against archaea. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 114 2457–2473. 10.1002/bit.26387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieco-Saiz N., Belguesmia Y., Raspoet R., Auclair E., Gancel F., Kempf I., et al. (2019). Benefits and inputs from Lactic Acid Bacteria and their bacteriocins as alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters during food-animal production. Front. Microbiol. 10:57. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas D., McGeough E. J., McGinn S. M., McAllister T. A., Beanchemin K. A. (2014). Effect of Propionibacterium spp. on ruminal fermentation, nutrient digestibility, and methane emissions in beef heifers fed a high-forage diet. J. Anim. Sci. 92 2192–2201. 10.2527/jas2013-7492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R. J., Brammall M. L. (1985). The role of different species of bacteria in the hydrolysis of protein in the rumen. Microbiology 131 821–832. 10.1099/00221287-131-4-821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wedlock D. N., Janssen P. H., Leahy S. C., Shu D., Buddle B. M. (2013). Progress in the development of vaccines against rumen methanogens. Animal 7:(Suppl 2), 244–252. 10.1017/S1751731113000682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimar M. R., Cheung J., Dey D., McSweeney C., Morrison M., Kobayashi Y., et al. (2017). Development of multiwell-plate methods using pure cultures of methanogens to identify new inhibitors for suppressing ruminant methane emissions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83:e00396-e17. 10.1128/AEM.00396-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg Z. G., Muck R. E. (1996). New trends and opportunities in the development and use of inoculants for silage. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 19 53–68. 10.1016/0168-6445(96)00025-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg Z. G., Muck R. E. (2013). “Potential probiotic effects of lactic acid bacteria on ruminant performance,” in Proceedings of the III International Symposium on Forage Quality and Conservation, (Piracicaba, SP: FEALQ; ), 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg Z. G., Muck R. E., Weimer P. J. (2003). The survival of silage inoculant lactic acid bacteria in rumen fluid. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94 1066–1071. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg Z. G., Muck R. E., Weimer P. J., Chen Y., Gamburg M. (2004). Lactic acid bacteria used in inoculants for silage as probiotics for ruminants. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 118 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss W. P., Wyatt D. J., McKelvey T. R. (2008). Effect of feeding propionibacteria on milk production by early lactation dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 91 646–652. 10.3168/jds.2007-0693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford M. F., McPherson M. A., Forster R. J., Teather R. M. (2001). Identification of bacteriocin-like inhibitors from rumen Streptococcus spp. and isolation and characterization of bovicin 255. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 569–574. 10.1128/aem.67.2.569-574.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisener L. V., Sargeant J. M., O’Conner A. M., Faires M. C., Glass-Kaastra S. K. (2015). The use of direct-fed microbials to reduce shedding of Escherichia coli O157 in beef cattle: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Zoonoses Public Health 62 75–89. 10.1111/zph.12112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollenberg E., Richards M., Smith P., Havlik P., Obersteiner M., Tubiello F. N., et al. (2016). Reducing emissions from agriculture to meet the 2 °C target. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22 3859–3864. 10.1111/gcb.13340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Huang W., Hou Q., Kwok L., Sun A., Ma H., et al. (2017). The effects of probiotics administration on the milk production, milk components and fecal bacteria microbiota of dairy cows. Sci. Bull. 62 767–774. 10.1016/j.scib.2017.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]