Abstract

The purpose of this study was to characterize changes in gene expression in the brain of a seasonal hibernator, the golden-mantled ground squirrel, Spermophilus lateralis, during the hibernation season. Very little information is available on molecular changes that correlate with hibernation state, and what has been done focused mainly on seasonal changes in peripheral tissues. We produced over 4000 reverse transcription-PCR products from euthermic and hibernating brain and compared them using differential display. Twenty-nine of the most promising were examined by Northern analysis. Although some small differences were observed across hibernation states, none of the 29 had significant changes. However, a more direct approach, investigating expression of putative hibernation-responsive genes by Northern analysis, revealed an increase in expression of transcription factors c-fos, junB, and c-Jun, but not junD, commencing during late torpor and peaking during the arousal phase of individual hibernation bouts. In contrast, prostaglandin D2 synthase declined during late torpor and arousal but returned to a high level on return to euthermia. Other genes that have putative roles in mammalian sleep or specific brain functions, including somatostatin, enkephalin, growth-associated protein 43, glutamate acid decarboxylases 65/67, histidine decarboxylase, and a sleep-related transcript SD464 did not change significantly during individual hibernation bouts. We also observed no decline in total RNA or total mRNA during torpor; such a decline had been previously hypothesized. Therefore, it appears that the dramatic changes in body temperature and other physiological variables that accompany hibernation involve only modest reprogramming of gene expression or steady-state mRNA levels.

Keywords: prostaglandin D2, enkephalin, c-fos, immediate early genes, ddPCR, mRNA

Hibernation has fascinated people for centuries, but little is known about the mechanisms controlling the hibernation process in mammals. Contrary to popular belief, small hibernating mammals do not remain torpid throughout the hibernation season. These hibernators exhibit periodic bouts of torpor throughout the winter, marked by dramatic changes in physiological variables, such as body temperature (Tb). Both entrance into and arousal from torpor are regulated processes controlled by hypothalamic nuclei and other brain structures (Heller et al., 1978;Kilduff et al., 1990). Neural activity, as well as all metabolic activity, is greatly reduced at the low temperatures associated with deep torpor (Walker et al., 1977; Heller, 1979; Krilowicz et al., 1988). Nevertheless, physiological regulation continues, and arousals appear to be precisely timed (Grahn et al., 1994). Given the duration and dramatic physiological changes that accompany hibernation events, changes in gene expression are probably involved.

In this study, two approaches were used to detect changes in gene expression during hibernation. First, random mRNAs were compared in brain samples from euthermic versus hibernating animals using a differential display PCR method (ddPCR). One advantage of this technique is that no prior assumptions are made as to which mRNAs are most likely to change. In the second approach, changes in abundance of specific mRNAs were tested by Northern analysis. The genes examined were selected based on expression patterns in brain and previous evidence for involvement in arousal state control.

Specifically, we chose six categories of genes. The first category is immediate early genes (IEGs). IEGs, including c-fos, junB, c-jun, junD, NGFI-A, and others, are transcription factors that respond to environmental stimulation within minutes. The role of IEG expression in the CNS has been well documented (Sheng and Greenberg, 1990; Morgan and Curran, 1991) and has been implicated in sleep, circadian rhythms, and hibernation (Sutin and Kilduff, 1992; Grassi-Zucconi et al., 1993; O’Hara et al., 1993, 1997; Bitting et al., 1994; Pompeiano et al., 1994). The second category includes enkephalin and somatostatin. Numerous studies have implicated the opioid system in hibernation and, to a lesser extent, somatostatin (Beckman et al., 1981, 1986; Beckman and Llados-Eckman, 1985; Nurnberger et al., 1991, 1997; Wang, 1993). The third is prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) synthase. PGD2 has been shown to increase seasonally in a hibernator (Takahata et al., 1996), induce sleep when injected intracerebroventricularly (Matsumura et al., 1994; Hayaishi, 1997; Ram et al., 1997), and reduce somatosensory pain perception (Minami et al., 1996). The fourth, the SD464 clone, was isolated by Rhyner et al. (1990) for its possible role in sleep homeostasis. The fifth category is glutamic acid decarboxylases GAD65 and GAD67 and histidine decarboxylase. GAD65 and GAD67 synthesize GABA (Erlander et al., 1991), the dominant inhibitory neurotransmitter in brain. Histidine decarboxylase produces histamine (Joseph et al., 1990), which may play a major role in arousal state control (Sherin et al., 1998). The last is growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43). Changes in dendritic spines have been reported during torpor (Popov and Bocharova, 1992; Popov et al., 1992), and GAP43 is strongly associated with synaptic plasticity (Skene et al., 1986; Benowitz and Routtenberg, 1987; Neve et al., 1987).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

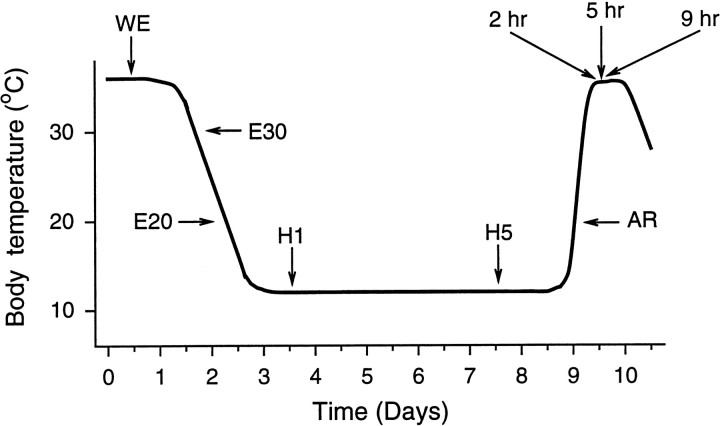

Animals. Golden-mantled ground squirrels,Spermophilus lateralis, were trapped during the summer months in Alpine and El Dorado Counties of the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. Both male and female animals were used in this study. Animals were implanted with abdominal temperature transmitters (Mini-Mitter Co., Sunriver, OR), and Tb was monitored continuously during the hibernation season. At the time the animals were killed, all Tb measurements were confirmed with a thermocouple probe placed in one or more of the following locations: rectal, abdominal, thoracic, and occasionally into the brain. Temperature measurements in different locations were all similar, although the head is known to warm first during arousal. Animals were maintained at an ambient temperature of 5°C in a constant 12 hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 8:00 A.M.). Animals were killed by decapitation during a 3 hr “window” between 1:00 and 4:00 P.M. during lights on. Although circadian rhythms of temperature persist throughout the hibernation season (Grahn et al., 1994), the rhythms appear to be primarily desynchronized from the light cycle (Pohl, 1987; our unpublished observations). Most squirrels were killed in one of five phases of the hibernation cycle as indicated in Figure1: (1) euthermia (winter) (Tbof 37°C); (2) midentrance (Tb of 20°C); (3) day 1 of deep hibernation (Tb of 7–8°C); (4) day 4, 5, or 6 of deep hibernation (Tb of 7–8°C); and (5) midarousal from hibernation (Tb of 20°C), which typically occurs ∼1 hr after body temperature begins to rise. A smaller number of squirrels were killed during the summer active phase (Tb of 37°C) at early entrance (Tb of 30°C) or at 2, 5, or 9 hr after arousal (from Tb of 20°C). The 2, 5, and 9 postarousal animals all had a Tb of 37°C and were the same as other winter euthermic animals (sometimes called interbout animals), except that postarousal time was precisely determined. Summer active squirrels had not hibernated for at least 3 weeks. Approximately 50 squirrels were continuously monitored to obtain animal(s) at each specific phase, at the designated time of day.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of a bout of torpor during the hibernation season. Bouts of torpor lasting several days to >1 week are interspersed with periodic returns to euthermia, referred to as winter euthermia or interbout euthermia. Arrowsindicate times at which samples were taken. WE, Winter euthermic (Tb of 37°C); E30, entrance (Tb of 30°C); E20, entrance (Tb of 20°C); H1, hibernation day 1 (Tb of 7°C); H5, hibernation day 5 (Tb of 7°C); AR, arousal (Tbof 20°C); 2 hr, 5 hr, and 9 hr, refer to postarousal time (Tb of 37°C) and are abbreviated in other figures as P2,P5, and P9.

RNA isolation and Northern analysis. After decapitation, brains were rapidly removed and dissected into 12 subregions (hypothalamus, thalamus, cerebral cortex, basal forebrain, septum, hippocampus, striatum, midbrain, cerebellum, pons, medulla, and pineal). Many peripheral tissues were taken, as well. All tissues were frozen on dry ice and stored at −70°C. Total RNA was extracted using a guanidinium–CsCl method or Trizol (BRL, Grand Island, NY), fractionated on 1.2% formaldehyde–agarose gels, and transferred to Nytran membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH). RNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining and cross-linked by UV irradiation. After prehybridization, membranes were hybridized at 42°C in 5× SSC, 50% formamide, 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 6.8, 1% SDS, 1 mm EDTA, 2.5× Denhardt’s solution, 200 mg/ml herring sperm DNA, and 4–10 × 106 cpm/ml32P-radiolabeled random-primed cDNA probe. After hybridization, membranes were washed two times for 30 min at 58°C in 0.4× SSC and 0.5% SDS. Filters were then exposed to Kodak XAR5 film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 1–12 d, and the band intensity was quantitated using a computer-assisted image analysis system using the film exposure with the optimal densities of each band (i.e., within the linear range) (MCID; Imaging Research, Inc., St. Catharines, Ontario). To control for variability in loading and transfer, all membranes were probed with a 700 bp human β-actin probe. β-Actin mRNA levels appear to remain constant throughout the hibernation cycle based on our comparisons of total RNA loaded and β-actin band density of hundreds of samples from different stages of hibernation. Multiple probings of the same Northern filters were carefully monitored to ensure that no residual radioactivity from previous probes remained and that no other degradation of the filters was apparent.

Most hybridization probes of the known genes used in this study were derived from gel-isolated fragments of rat, mouse, or human cDNA sequences that are well conserved across mammalian species. Three cDNAs, F1-ATPase, RNA poly(A) polymerase, and NADH-ubiquinone oxireductase, were isolated from a closely related species of squirrel,Spermophilus richardsonii (Srere, 1995). The 29 ddPCR fragments were unknown cDNA sequences from Spermophilus lateralis. The precise regions of each cDNA used to probe for c-fos, junB, c-jun, junD, NGFI-A, enkephalin, somatostatin, GAD65, GAD67, β-actin, and GAP43 were described previously (O’Hara et al., 1989, 1994, 1995, 1997). For other genes, cDNAs containing all or most of the coding sequence were used and can be found in PGD2 synthase (Urade et al., 1993), SD464 (Rhyner et al., 1990), cyclophilin (Hasel et al., 1991), and histidine decarboxylase (Joseph et al., 1990).

ddPCR. All ddPCR experiments were performed with total RNA derived from the cerebral cortex of Spermophilus lateralisto have sufficient RNA for both ddPCR and for subsequent Northern analyses to test putative positives. RNA derived from squirrels killed on day 4 of torpor (hibernation day 4), during the interbout euthermic period (winter euthermia), or during the summer active phase (summer euthermia) were compared. RNA samples were DNase treated and phenol-chloroform extracted before reverse transcription. The reverse transcription reaction was performed using 0.2 μg of DNA-free RNA in a 20 μl volume containing 20 mm dNTPs, 125 mmTris-HCl, pH 8.3, 188 mm KCl, 7.5 mmMgCl2, 25 mm DTT, and 100 U of MMLV reverse transcriptase in separate reactions containing 0.2 mm 3′ primers anchored to subsets of the RNA pool by single base changes [poly-dT11A, poly-dT11G, poly-dT11C, and poly-dT11T supplied in kit form (GenHunter Corp., Nashville, TN)]. Reactions were performed at 37°C for 1 hr after an initial 65°C denaturation step to allow annealing of the primers. One-tenth of the reverse transcription reaction product from each reaction was used in each subsequent PCR amplification using the original 3′ primer, in conjunction with random 13-mers as 5′ primers (GenHunter Corp.). PCR reactions contained 2 mm each 3′ and 5′ primers, 25 mm dNTPs, 2 μl of reverse transcription reaction product, PCR buffer (GenHunter Corp.), [α-35S]dATP (1200 Ci/mmol), and Amplitaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Emeryville, CA). PCR conditions were 94°C for 30 sec, 40°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 30 sec, each for 40 cycles. PCR products were analyzed on 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels, and banding patterns were compared between conditions. Forty-five primer combinations were used, and ∼100 bands could be visualized with each primer set. Therefore, in theory, ∼4500 mRNA transcripts were compared between deep hibernation and euthermic conditions, although there is likely to be some redundant cDNAs amplified by different primer sets. Most analyses compared summer euthermia versus deep hibernation.

Data analysis. The resultant data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Wherever post hoc tests were indicated, the data were analyzed by both Fisher’s protected least significance difference test and Scheffe’s F test; the results presented are only those in which these tests agree as to significance.

RESULTS

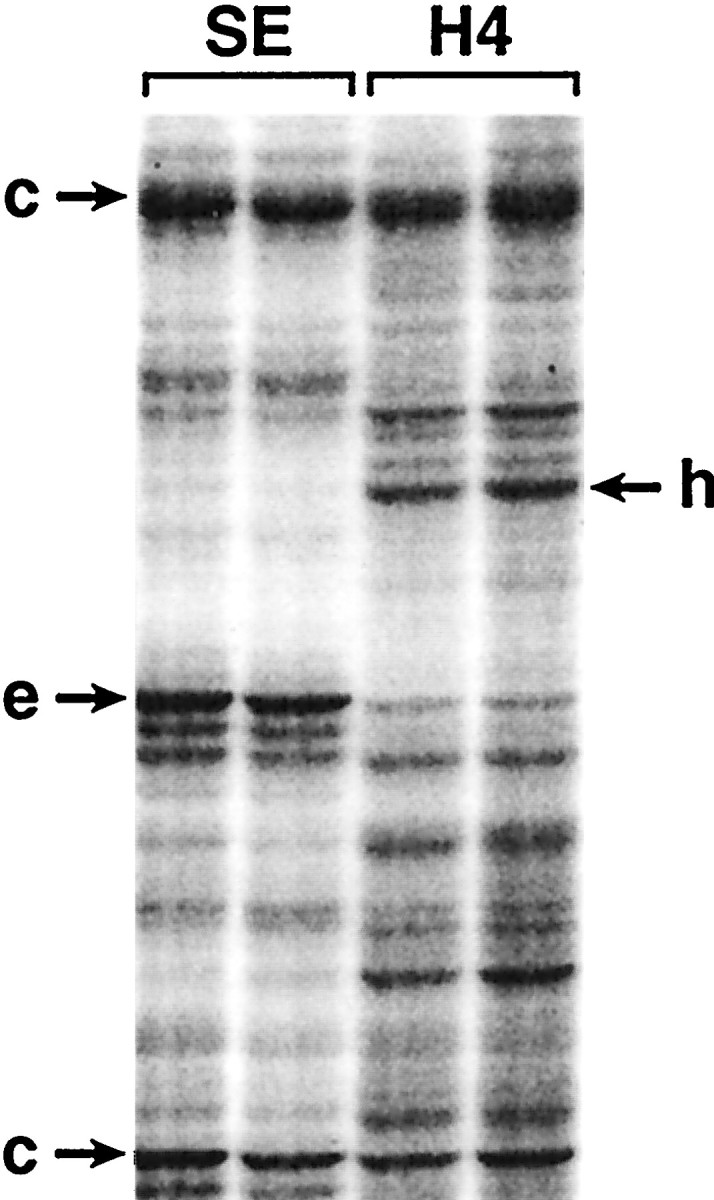

Changes in mRNA expression assayed by ddPCR

Samples of total RNA isolated from ground squirrel cortex during summer euthermia, the winter interbout euthermic period, and the fourth day of torpor, were used as templates to generate cDNA fragments, which were then amplified by PCR and separated on polyacrylamide gels. Differences in expression between test conditions were visualized by autoradiography of 35S-labeled bands (Fig. 2). Most comparisons were between summer euthermia and winter torpor (day 4 of a single hibernation bout) because these two states were hypothesized to have the most differences in gene expression. The initial screen of 4500 transcripts (in theory) produced 29 bands, indicating differences between these two states. These bands were cut out and reamplified for verification by Northern analysis on blots prepared from the initial RNA samples. All 29 probes produced distinctive bands, but none of the 29 putative differences in expression were significant when tested on Northern blots containing samples of summer euthermia and winter hibernation (data not shown). Therefore, no enrichment of hibernation-responsive genes was achieved by this method. However, the fact that 29 of 29 selected cDNAs failed to show any significant changes in steady-state mRNA levels suggests that the majority of mRNAs do not dramatically change in abundance across these conditions.

Fig. 2.

ddPCR. Samples of total RNA were isolated from ground squirrel cortex during summer euthermia and hibernation day 4. The isolated RNAs were used as templates in duplicate to generate cDNA fragments, which were then amplified by PCR and separated on polyacrylamide gels. SE, Summer euthermic;H4, hibernation day 4; c→, bands that appear to remain constant across the two conditions;e→, bands that appear to be more abundant during euthermia; ←h, bands that appear to be more abundant during hibernation.

Changes in mRNAs assayed by Northern analysis

In contrast to the ddPCR method, Northern analysis of selected, well characterized genes was used as a directed approach to test variability within the hibernation cycle. All cDNA probes produced one or two distinctive bands, with sizes, intensity (reflecting abundance), and expression patterns consistent with known data in the mouse, rat, and human. Some Northern analyses were run with RNA derived from multiple species to further support that each cDNA probe was recognizing its homolog in the squirrel.

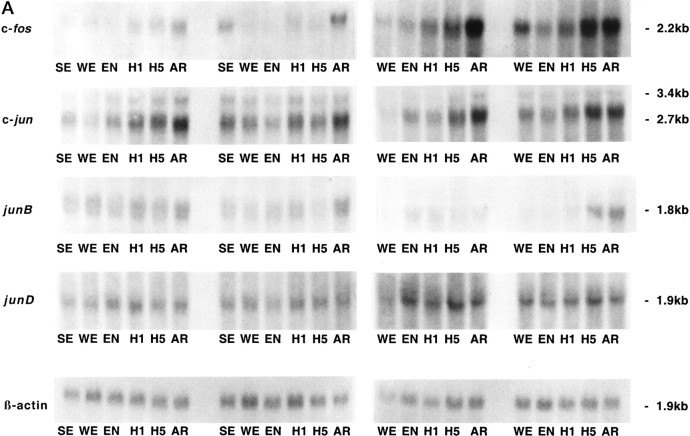

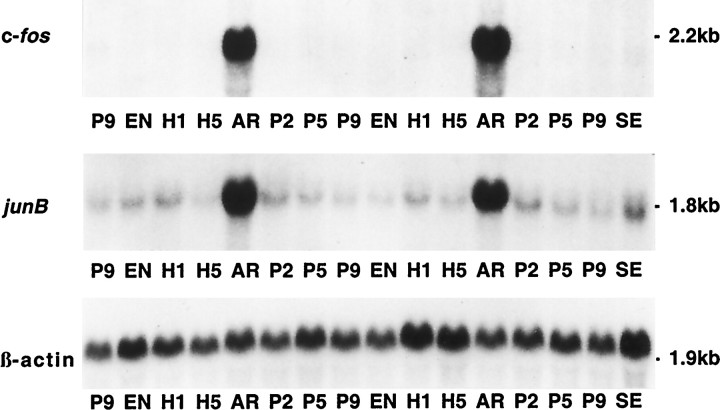

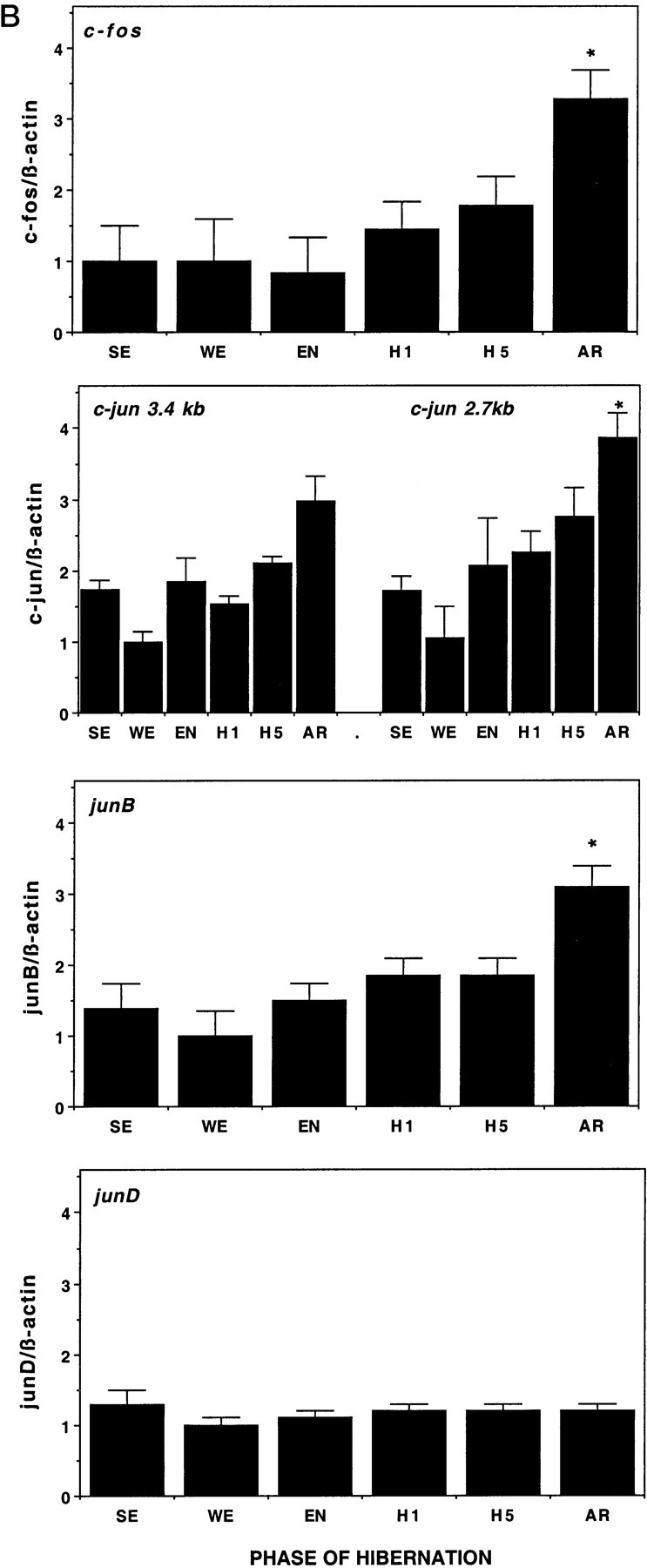

Differential expression among IEG family members was observed within the hypothalamus across the hibernation cycle. Whereas c-fos, junB, and c-Jun mRNAs appear to increase during torpor and peak during arousal in hypothalamus, junD remains constant (Fig.3). The increase in expression of c-fos and c-Jun during arousal is not confined to the hypothalamus but occurs in other brain regions, such as the cortex (Fig.4), and in almost every other brain region examined, including thalamus, basal forebrain, septum, hippocampus, striatum, midbrain, cerebellum, pons, and medulla (our unpublished observations). In a peripheral tissue, such as brown fat (Fig. 5), c-fos expression is dramatically higher during arousal but is virtually undetectable at other times and does not exhibit the trend toward higher expression during the latter part of torpor characteristic of hypothalamus (Fig.3). Liver and spleen also exhibit sharp rises in c-fos mRNA during arousal but have somewhat higher basal levels (our unpublished observations). To investigate the time course of c-fos expression in the hypothalamus in finer detail, samples were taken at additional time points. Figure 6 confirms that the peak in c-fos expression occurs during arousal from torpor, with a return to basal levels within 2 hr after arousal.

Fig. 3.

Expression of IEGs in hypothalamus across hibernation. A, Autoradiographs of Northern blots of total RNA (20 μg/lane) isolated from hypothalamus of ground squirrels killed during different phases of the hibernation cycle and hybridized to [32P]-labeled c-fos, c-jun, junB, and junD cDNA probes. Sizes of mRNAs are shown to the right in kilobases. Note the increasing levels of both c-fos and c-jun mRNA during late torpor and then peaking during arousal relative to other phases of hibernation. The c-fos probing on the left and rightwere done at different times with different specific activity and total counts per minutes and do not represent differences in c-fos expression between these groups. Each blot was normalized internally for statistical analyses shown in the histograms in B.SE, Summer euthermic; WE, winter euthermic; EN, entrance; H1, hibernation day 1; H5, hibernation day 5; AR, arousal. β-actin mRNA serves as a control for RNA loading in each lane. n = 4 for each condition during the hibernation season, and n = 2 for summer euthermia (SE). B, Quantitation of the relative mRNA levels are shown based on band density of the autoradiograms inA. Each graph displays means ± SEs. To control for variability in loading and transfer, all data are presented relative to β-actin, whose expression remains constant throughout the hibernation cycle relative to total RNA and total mRNA (data not shown). mRNA levels of c-fos, c-jun, and junB during arousal (AR) are significantly elevated relative to baseline winter euthermic levels. *p < 0.01.

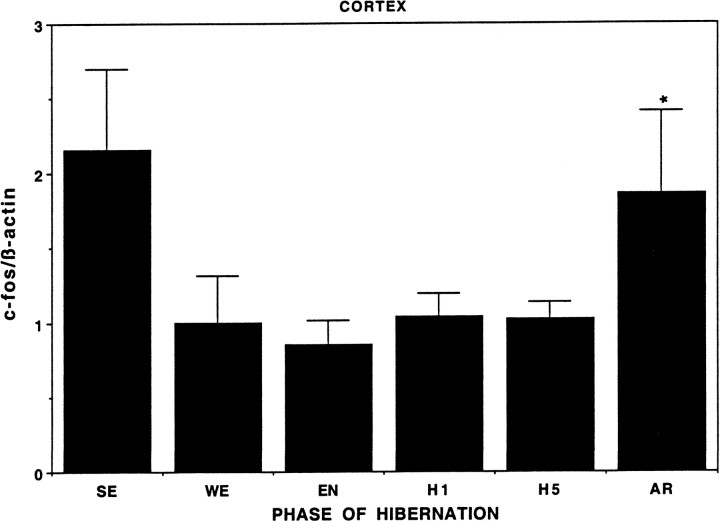

Fig. 4.

Quantitation of relative c-fos mRNA levels in cortex. Graphic representation of c-fos mRNA levels in the cerebral cortex across different hibernation states as shown with hypothalamus in this and Figure 3. n = 4 for WE,EN, H1, H5, andAR. n = 2 for SE. The cortical samples were derived from the same animals as hypothalamus. Abbreviations as in Figure 3. Note that c-fos mRNA levels are again significantly elevated in AR relative toWE, EN, H1, andH5. *p < 0.05.SE levels of c-fos mRNA also appear to be elevated but could not be supported statistically because n = 2.

Fig. 5.

Expression of c-fos and junB in brown fat. Autoradiographs of Northern blots of total RNA (20 μg/lane) isolated from brown adipose tissue of squirrels at different phases of the hibernation cycle. Note the extremely low basal level of c-fos mRNA and the very strong induction during arousal. P2, 2 hr after arousal; P5, 5 hr after arousal; P9, 9 hr after arousal (from a Tb of 20°C); SE, summer euthermic; EN, entrance; H1, hibernation day 1; H5, hibernation day 5;AR, arousal. β-actin mRNA serves as a control to assess RNA loading in each lane.

Fig. 6.

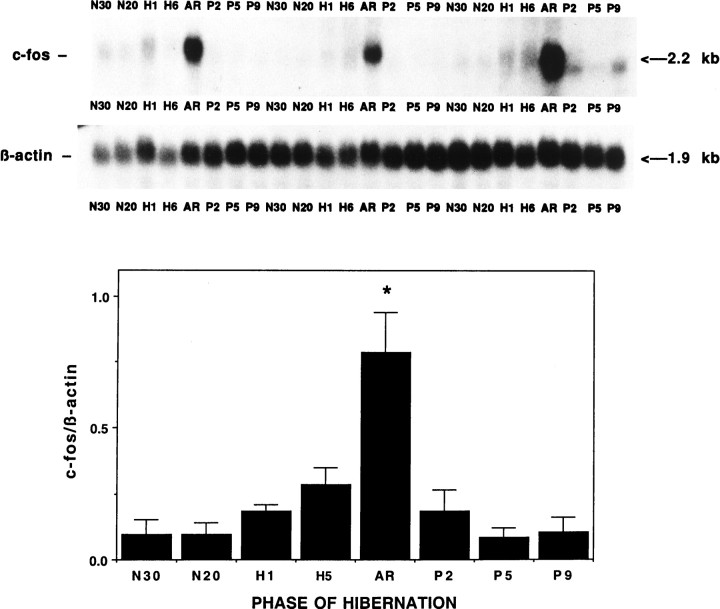

Rapid return of c-fos mRNA levels after arousal. Autoradiographs of Northern blots of total RNA (20 μg/lane) isolated from hypothalamus of ground squirrels killed during different phases of the hibernation cycle as in Figure 3, with the addition of several well defined postarousal time points and one additional entrance time point (N30). N30 is early entrance to torpor (Tb of 30°C), and N20 is midentrance (Tb of 20°C), the same as EN in other figures. Note the increasing amount of c-fos mRNA during torpor and the high peak during arousal as in Figure 3, and then the rapid return to basal levels after arousal. Levels of c-fos mRNA during arousal are significantly elevated over all other phases; *p < 0.01. n = 3 for each condition. Other abbreviations as in Figures 3-5.

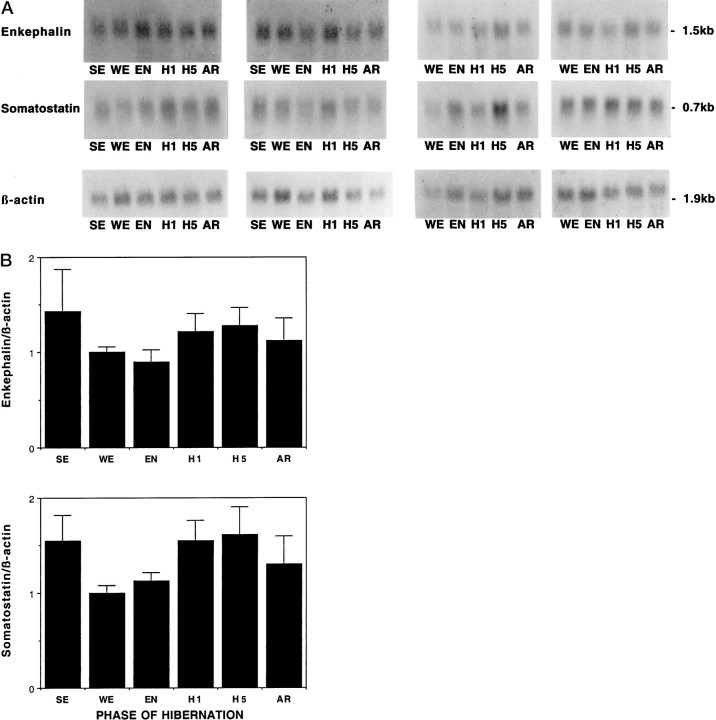

In contrast to the IEGs, two neuropeptide mRNAs known to be expressed in hypothalamus, somatostatin and enkephalin, did not undergo significant changes across the hibernation cycle (Fig.7), despite previous evidence for changes in peptide or mRNA levels (Nurnberger et al., 1991, 1997).

Fig. 7.

Somatostatin and enkephalin mRNA levels show no change across hibernation. A, Autoradiographs of Northern blots of total RNA (20 μg/lane) isolated from the hypothalamus of ground squirrels using the same filters as in Figure 3and hybridized to [32P]-labeled somatostatin and enkephalin cDNA probes. Abbreviations as in Figure 3. B, Quantitation of relative mRNA levels of somatostatin and enkephalin across hibernation. Graphic representation of band intensity was quantitated by optical density. To control for variability in loading and transfer, all data are presented relative to β-actin as in other figures. No significant change for either mRNA occurs across these conditions.

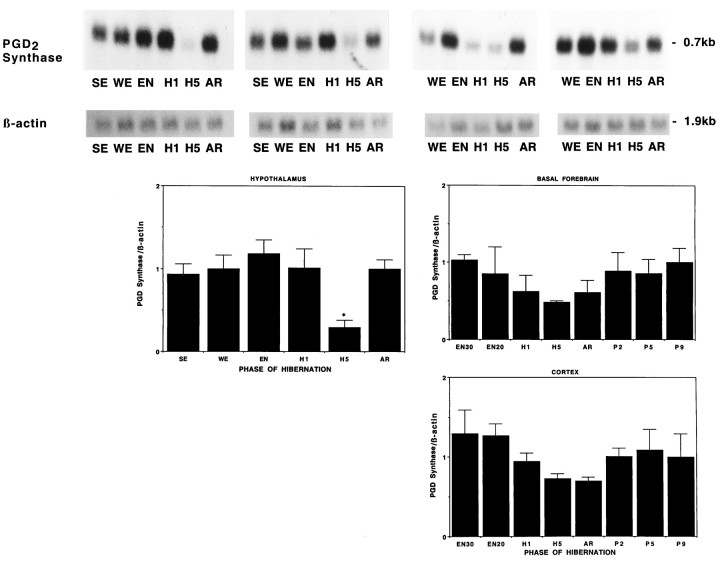

Figure 8 illustrates that PGD2 synthase mRNA varies significantly over the hibernation cycle, declining sharply in the hypothalamus after many days of hibernation, and returning to its former level during arousal, whereas the cortex and basal forebrain both show a more modest decline that does not quite reach statistical significance.

Fig. 8.

PGD2 synthase mRNA declines during torpor. Autoradiographs of Northern blots of total RNA (20 μg/lane) isolated from hypothalamus along with graphic representations of hypothalamus, cerebral cortex, and basal forebrain of ground squirrels killed during different phases of hibernation cycle and hybridized to a [32P]-labeled PGD2 synthase cDNA probe. Note the decreased level of PGD2 synthase mRNA during late torpor in the hypothalamus relative to all other conditions; *p< 0.05. The lower levels of PGD2 synthase mRNA in the cortex and basal forebrain during late torpor and arousal do not quite reach statistical significance. Filters for the hypothalamus are the same as used previously, and the cortical and basal forebrain samples are from the same animals as the hypothalamus shown in Figure 6.

Several other genes were examined, including GAD65, GAD67, histidine decarboxylase, SD464, GAP43, cyclophilin, and three housekeeping genes whose expression in the liver varies across the hibernation season (Srere, 1995). No significant changes in steady-state mRNA levels were found in the brain for any of these genes across phases of hibernation. These genes, along with those described above, are summarized in Table1. Only some IEGs and PGD2 synthase were found to exhibit significant differences in steady-state mRNA levels across different phases of hibernation. For most genes, the within-group variation was modest, and differences in mRNA abundance greater than twofold would usually be detected as significant.

Table 1.

Changes in mRNA levels across the hibernation cycle

| Immediate early genes | |

| c-fos | ↑AR (multiple brain regions) |

| c-jun | ↑AR (multiple brain regions) |

| junB | ↑AR (multiple brain regions) |

| junD | ←NSC→ (multiple brain regions) |

| NGFI-A | ↑AR (multiple brain regions) |

| Neuropeptides | |

| somatostatin | ←NSC→ (multiple brain regions) |

| enkephalin | ←NSC→ (multiple brain regions) |

| Prostaglandin D2 synthase | ↓H5 (hypothalamus) |

| Sleep deprivation cDNA 464 | ←NSC→ (multiple brain regions) |

| Glutamic acid decarboxylases | |

| GAD65 | ←NSC→ (hypothalamus) |

| GAD67 | ←NSC→ (hypothalamus) |

| Histidine decarboxylase | ←NSC→ (hypothalamus) |

| GAP 43 | ←NSC→ (cortex, hippocampus) |

| Control genes | |

| β-actin | ←NSC→ (multiple brain regions) |

| Cyclophillin | ←NSC→ (multiple brain regions) |

| Housekeeping genes reported to change in liver (Srere, 1995) | |

| F1-ATPase | ←NSC→ (cortex) |

| RNA poly(A) polymerase | ←NSC→ (multiple brain regions) |

| NADH-ubiquninone oxireductase | ←NSC→ (multiple brain regions) |

| 29 ddPCR probes | ←NSC→ (cortex) |

NSC, No significant change.

DISCUSSION

We have investigated changes in mRNA levels in the brain from a variety of genes across phases of hibernation in the golden-mantled ground squirrel. Considerable evidence suggests that the brain plays a major role in regulating the extreme changes in body temperature, metabolism, and other physiological variables that accompany hibernation (Mihailovic, 1972; Heller and Colliver, 1974; Heller, 1979;Dark et al., 1990). The hypothalamus in particular appears to play a critical role in both the entrance to and arousal from each hibernation bout (Heller, 1979; Kilduff et al., 1990) and was studied most extensively in this paper. The cerebral cortex was also of interest because this brain region has provided measures of arousal state variation across hibernation using conventional EEG monitoring (Mihailovic, 1972; Walker et al., 1977), and suppression of metabolic activity in this structure has been implicated in the entrance to hibernation (Kilduff et al., 1990). In general, other brain regions, such as hippocampus and basal forebrain, were similar to cortex for all of the mRNAs studied (unpublished data). Brain regions aside from hypothalamus, cortex, hippocampus, and basal forebrain were studied in only a few samples because there did not appear to be any dramatic regional differences. The hypothalamus, as the prime region of focus, did display some potentially unique characteristics, such as increases in IEG mRNAs as each torpor bout progressed, as opposed to increases only at arousal. The hypothalamus also displayed the only significant change in PGD2 mRNA levels and the most rapid rise in PGD2 mRNA during arousal.

Across all mRNAs studied, we were somewhat surprised by the constancy of mRNA levels given the extreme physiological changes that accompany hibernation. Because the ddPCR compared summer euthermic versus deep torpor, it could have identified genes that regulate the hibernation process, genes that respond to the seasonal changes, or genes that change with body temperature, metabolism, etc. The ddPCR method can produce false positives (Debouck, 1995), and that appears to have occurred in this study. Nonetheless, these experiments did provide a sample of 29 different cDNAs. The fact that none of the ddPCR products and only one known gene examined, PGD2 synthase, declined significantly during torpor may be particularly worth noting. At the low body temperatures achieved during hibernation (8°C or less under our ambient conditions of 5°C), it seemed likely that RNA transcription might virtually cease, and all RNAs would either be maintained or would decrease in abundance. In fact, such a decline might explain the mystery of periodic arousals throughout the hibernation season, which are metabolically costly and limit the energy conservation achieved (Lyman et al., 1982). However, we found no evidence for a general decline in total RNA yields, mRNA yields, or specific mRNAs tested, consistent with recent work in some peripheral tissues (Srere et al., 1992; Carey and Martin, 1996). Instead, some mRNAs (e.g., c-fos, c-jun) in our study appear to increase in the brain during torpor, although these changes do not reach statistical significance until the arousal phase. In peripheral tissues, a small number of mRNAs and proteins have been found to vary between torpor and euthermia, with examples of both increasing (Srere et al., 1992; Wilson et al., 1992; Andrews et al., 1998; Gorham et al., 1998) and decreasing expression (Kondo and Kondo, 1992; Takamatsu et al., 1997), which are concordant at the mRNA and protein levels in all cases examined. None of these other studies, however, focus on the detailed time points across hibernation bouts, especially the dramatic periods of arousal from and entrance to hibernation.

In this report, we found that basal levels of IEG mRNAs were clearly higher in the brain than in brown fat and other peripheral tissues (Figs. 3-5; our unpublished observations). These data strengthen the argument that the brain is relatively more active during hibernation than many peripheral tissues. Furthermore, because there does not appear to be a general decline in most mRNAs (which might appear as relative increases in some genes), it is extremely likely that substantial new transcription of some genes does take place during arousal from hibernation (as indicated by c-fos induction) and that, in hypothalamus, this may occur even at the coldest body temperatures during torpor. It does not seem likely that the large increases in IEG mRNAs could occur only by changes in mRNA stability. In addition, our data may be relevant to the fact that animals are increasingly responsive to stimuli as each bout of hibernation progresses (Beckman and Stanton, 1976), suggesting the possibility of increasing CNS function and the need for new mRNA synthesis.

Our inability to detect significant changes in enkephalin or somatostatin mRNA, despite changes at the protein level (Nurnberger et al., 1991, 1997), suggests regulation at steps other than transcription, although it is possible that our nonsignificant increase in enkephalin mRNA does underlie the significant differences at the protein level or that changes in enkephalin occur in a relatively small percentage of enkephalin neurons. Because of individual variability, sample size, and technical limitations in the quantification of mRNA levels, our study was designed to detect relatively large changes in gene expression of greater than twofold. There are probably many important smaller changes in gene expression that, in concert, play an important or even dominant role. In fact, the small number of genes we have found with large changes makes this possibility likely.

In contrast to the majority of genes, IEG expression can vary widely across experimental conditions (Bartel et al., 1989; Sheng and Greenberg, 1990; Morgan and Curran, 1991; Sutin and Kilduff, 1992), as we found to occur across hibernation. This is especially apparent in brown fat (Fig. 5) in which levels are barely detectable but rise dramatically during arousal. Although c-fos levels in the brain also exhibit this induction, basal levels are much higher and, as noted above, appear to increase late in torpor in some brain regions, such as hypothalamus. Both the higher basal level and the possible earlier induction in the hypothalamus suggest a central role in regulatory control. We have found previously that the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus undergoes a dramatic induction of c-fos mRNA during the arousal phase (Bitting et al., 1994); however, thein situ methodology used was not sensitive enough to measure c-fos in other brain regions. Our current study shows that c-fos induction during arousal occurs throughout the brain and in most peripheral tissues as well, although the hypothalamus continues to stand out as the most dynamic brain region (both in terms of IEG and PGD2 synthase mRNAs). The cerebral cortex has a relatively high basal level of c-fos but shows no increase in late torpor. Aside from hibernation, c-fos levels in the cortex correlate well with activity and sleep (Grassi-Zucconi et al., 1993; Pompeiano et al., 1994; O’Hara et al., 1997). Therefore, the higher levels of c-fos mRNA in the cortex of summer active animals (Fig. 4) may reflect higher activity of the squirrels at this time, although because of the availability of only two summer active animals, this difference could not be established statistically. The rapid decline of c-fos mRNA in the hypothalamus after arousal may also be in part caused by sleep, because the initial period of interbout euthermia almost invariably contains very deep sleep (Daan et al., 1991; Trachsel et al., 1991; Kilduff et al., 1993). Because IEGs are transcription factors, we are currently investigating this postarousal period in greater detail to determine which genes may be subsequently activated or inactivated. An important determining factor in target gene activation by FOS/JUN heterodimers is which JUN partner is paired with FOS (Ryseck and Bravo, 1991). Therefore, it is relevant to note that c-jun and junB both increase along with c-fos mRNA, but junD remains constant. In studies of IEG expression in the rat across circadian time and arousal states, c-fos and junB both increase with periods of high locomotor activity, whereas junD and c-jun remain invariant (O’Hara et al., 1993, 1997). In contrast, squirrels appear to use c-jun induction together with c-fos and junB (O’Hara et al., 1997) (Fig. 3).

As with the rapid decline in c-fos mRNA after arousal, the change in PGD2 synthase mRNA levels may also reflect relationships between hibernation and sleep (Heller, 1979; Kilduff et al., 1993). Prostaglandins are locally acting hormones produced from metabolism of arachidonic acid by the cyclooxygenase pathway. PGD2 both induces sleep (Hayaishi, 1997; Ram et al., 1997) and reduces somatosensory pain perception (Minami et al., 1996). PGD2 circulates within the CNS in the ventricular system and subarachnoid space and is produced primarily by choroid plexus and leptomeninges, and to a lesser extent by glia and neurons (Urade et al., 1993). We do not believe any of our samples contain choroid plexus or leptomeninges; therefore, we are most likely measuring the lower levels of expression in the neurons and glia of each brain region. PGD2 has also been shown to increase seasonally in the Asian chipmunk, another mammalian hibernator (Takahata et al., 1996). Interestingly, not only is there a decline in PGD2 synthase mRNA during late torpor but a subsequent rapid return to high expression during arousal in the hypothalamus and during interbout euthermia in the basal forebrain and cortex. The basal forebrain is the most responsive brain region with respect to the sleep promoting ability of PGD2 (Matsumura et al., 1994), and this may therefore relate to the hypersomnia of the postarousal period (Trachsel et al., 1991).

In summary, our findings suggest that only a small percentage of mRNAs undergo large changes in steady-state levels in the brain across the hibernation cycle. The mRNAs identified that do undergo large changes, IEGs and PGD2 synthase, seem likely to play important roles in the extreme physiological and arousal state changes that accompany individual hibernation bouts.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Army Research Office Grant DAAH04-95-1-0616, National Institutes of Health Grants DA00187 and HL58985, and a grant from the Upjohn Company. This article is dedicated to the memory of Louise Bitting (1/20/49 to 1/9/99), whose creativity and love of science and life were an inspiration to all who knew her.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Bruce F. O’Hara, Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5020.

Dr. Kilduff’s present address: Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory, SRI International, Menlo Park, CA 94025.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews MT, Squire TL, Bowen CM, Rollins MB. Low-temperature carbon utilization is regulated by novel gene activity in the heart of a hibernating mammal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8392–8397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel D, Sheng M, Lau LF, Greenberg ME. Growth factors and membrane depolarization activate distinct programs of early response gene expression. Genes Dev. 1989;3:304–313. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckman AL, Llados-Eckman C. Antagonism of brain opioid peptide action reduces hibernation bout duration. Brain Res. 1985;328:201–205. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckman AL, Stanton TL. Changes in CNS responsiveness during hibernation. Am J Physiol. 1976;231:810–816. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.3.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckman AL, Llados-Eckman C, Tanton TL, Adler MW. Physical dependence on morphine fails to develop during the hibernation state. Science. 1981;212:1527–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.7233241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckman AL, Dean RR, Wamsley JK. Hippocampal and cortical opioid receptor binding: changes related to the hibernation state. Brain Res. 1986;386:223–231. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benowitz L, Routtenberg A. A membrane phosphoprotein associated with neural development, axonal regeneration, phospholipid metabolism, and synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 1987;10:527–532. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bitting L, Sutin EL, Watson FL, Leard LE, O’Hara BF, Heller HC, Kilduff TS. C-fos mRNA increases in the ground squirrel suprachiasmatic nucleus during arousal from hibernation. Neurosci Lett. 1994;165:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90723-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carey HV, Martin SL. Perservation of intestinal gene expression during hibernation. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G804–G813. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.5.G805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daan S, Barnes BM, Strijkstra AM. Warming up for sleep? Ground squirrels sleep during arousals from hibernation. Neurosci Lett. 1991;128:265–268. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90276-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dark J, Kilduff TS, Heller HC, Licht P, Zucker I. Suprachiasmatic nuclei influence hibernation rhythms of golden-mantled ground squirrels. Brain Res. 1990;509:111–118. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debouck C. Differential display or differential dismay? Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1995;6:597–599. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlander M, Tillakaratne N, Feldblum S, Patel N, Tobin A. Two genes encode distinct decarboxylases. Neuron. 1991;7:91–100. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90077-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorham DA, Bretscher A, Carey HV. Hibernation induces expression of moesin in intestinal epithelial cells. Cryobiology. 1998;37:146–154. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1998.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grahn DA, Miller JD, Houng VS, Heller HC. Persistence of circadian rhythmicity in hibernating ground squirrels. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:R1251–R1258. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grassi-Zucconi G, Menegazzi M, De Prati AC, Bassetti A, Montagnese P, Mandile P, Cosi C, Bentivoglio M. c-fos mRNA is spontaneously induced in the rat brain during the activity period of the circadian cycle. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:1071–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasel KW, Glass JR, Godbout M, Sutcliffe JG. An endoplasmic reticulum-specific cyclophilin. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3484–3491. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.7.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayaishi O. Prostaglandin D synthase, β-trace and sleep. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;433:347–350. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1810-9_74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heller HC. Hibernation: neural aspects. Annu Rev Physiol. 1979;41:305–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.41.030179.001513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heller HC, Colliver GW. CNS regulation of body temperature during hibernation. Am J Physiol. 1974;227:583–589. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.227.3.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heller HC, Florant GL, Glotzbach SF, Walker JM, Berger RJ. Sleep and torpor—homologous adaptations for energy conservation. In: Clutter M, editor. Dormancy and developmental arrest. Academic; New York: 1978. pp. 269–296. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joseph DR, Sullivan PM, Wang YM, Kozak C, Fenstermacher DA, Behrendsen ME, Zahnow CA. Characterization and expression of the complementary DNA encoding rat histidine decarboxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:733–737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilduff TS, Miller JD, Radeke CM, Sharp FR, Heller HC. [14C]2-deoxyglucose uptake in ground squirrel brain during entrance to and arousal from hibernation. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2463–2475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02463.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilduff TS, Krilowicz B, Milsom W, Trachsel L, Wang LCH. Sleep and mammalian hibernation: homolgous adaptations and homologous processes? Sleep. 1993;16:372–386. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.4.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondo N, Kondo J. Identification of novel blood proteins specific for mammalian hibernation. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:473–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krilowicz BL, Glotzbach SF, Heller HC. Neuronal activity during sleep and complete bouts of hibernation. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:R1008–R1019. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.255.6.R1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyman CP, Willis JS, Malan A, Wang LC. Hibernation and torpor in mammals and birds, p 317. Academic; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumura H, Nakajima T, Osaka T, Satoh S, Kawase K, Kubo E, Kantha SS, Kasahara K, Hayaishi O. Prostaglandin D2-sensitive, sleep-promoting zone defined in the ventral surface of the rostral basal forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11998–12002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mihailovic LT. Cortical and subcortical electrical activity in hibernation and hypothermia. In: South FE, Hannon JP, Willis JR, Pengelley ET, Albert NR, editors. Hibernation and hypothermia: perspectives and challenges. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1972. pp. 487–534. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minami T, Okuda-Ashitaka E, Mori HH, Ito S, Hayaishi O. Prostaglandin D2 inhibits prostaglandin E2-induced allodynia in conscious mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:1146–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan JI, Curran T. Stimulus-transcription coupling in the nervous system: involvement of the inducible proto-oncogenes fos and jun. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:421–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neve R, Perrone-Bizzozero N, Finklestein S, Zwiers H, Bird E, Kurnit D, Benowitz L. The neuronal growth-associated protein GAP-43 (B-50, F1): neuronal specificity, developmental regulation and regional distribution of the human and rat mRNAs. Mol Brain Res. 1987;2:177–183. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(87)80012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nurnberger F, Lee T, Jourdan M, Wang LCH. Seasonal changes in methionine-enkephalin immunoreactivity in the brain of a hibernator, Spermophilus columbianus. Brain Res. 1991;547:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90581-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nurnberger F, Pleschka K, Masson-Pevet M, Pevet P. The somatostatin system of the brain and hibernation in the European hamster (Critcetus). Cell Tissue Res. 1997;288:441–447. doi: 10.1007/s004410050831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Hara BF, Fisher S, Oster-Granite ML, Gearhart JD, Reeves RH. Developmental expression of the amyloid precursor protein, growth-associated protein 43, and somatostatin in normal and trisomy 16 mice. Dev Brain Res. 1989;49:300–304. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Hara BF, Young KA, Watson FL, Heller HC, Kilduff TS. Immediate early gene expression in brain during sleep deprivation: preliminary observations. Sleep. 1993;16:1–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Hara BF, Donovan DM, Lindberg I, Brannock MT, Ricker DD, Moffatt CA, Klaunberg BA, Schindler C, Chang TSK, Nelson RJ, Uhl GR. Proenkephalin transgenic mice: High testis expression and possible infertility. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;38:275–284. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080380308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Hara BF, Andretic R, Heller HC, Carter DB, Kilduff TS. GABA-A, GABA-C, and NMDA receptor subunit expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and other brain regions. Mol Brain Res. 1995;28:239–250. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00212-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Hara BF, Watson FL, Wiler SW, Young KA, Bitting L, Heller HC, Kilduff TS. Daily variation of CNS gene expression in nocturnal vs diurnal rodents and in the developing brain. Mol Brain Res. 1997;48:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pohl H. Circadian pacemaker does not arrest in deep hibernation. Evidence for desychronization from the light cycle. Experientia. 1987;43:293–294. doi: 10.1007/BF01945554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pompeiano M, Cirelli C, Tononi G. Immediate early genes in spontaneous wakefulness and sleep: expression of c-fos and NGFI-A mRNA and protein. J Sleep Res. 1994;3:65–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1994.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popov V, Bocharova L. Hibernation-induced structural changes in synaptic contacts between mossy fibers and hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Neuroscience. 1992;48:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popov V, Bocharova L, Bragin A. Repeated changes of dendritic morphology in the hippocampus of ground squirrels in the course of hibernation. Neuroscience. 1992;48:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90336-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ram A, Pandey H, Matsumura H, Kasahara-Orita K, Nakajima T, Takahata R, Satoh S, Terao A, Hayaishi O. CSF levels of prostaglandins, especially the level of prostaglandin D2, are correlated with increased propensity towards sleep in rats. Brain Res. 1997;751:81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rhyner TA, Borbely AA, Mallet J. Molecular cloning of forebrain mRNAs which are modulated by sleep deprivation. Eur J Neurosci. 1990;2:1063–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1990.tb00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryseck RP, Bravo R. c-jun, JUN B, and JUN D differ in their binding affinities to AP-1 and CRE consensus sequences: effect of FOS proteins. Oncogene. 1991;6:533–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheng M, Greenberg ME. The regulation and function of c-fos and other immediate early genes in the nervous system. Neuron. 1990;4:477–485. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90106-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sherin JE, Elmquist JK, Torrealba F, Saper CB. Innervation of histaminergic tuberomammillary neurons by GABAergic and galaninergic neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus of the rat. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4705–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04705.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skene J, Jacobson R, Snipes G, McGuire C, Norden J, Freedman J. A protein induced during nerve growth, GAP-43, is widely distributed and developmentally regulated in rat CNS. J Neurosci. 1986;6:1843–1855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-06-01843.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srere HK. Molecular and structural analysis of mammalian liver during hibernation. PhD thesis, University of Colorado Health Science Center; Denver, CO: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srere HK, Wang LC, Martin SL. Central role for differential gene expression in mammalian hibernation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7119–7123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sutin EL, Kilduff TS. Circadian and light-induced expression of immediate early gene mRNAs in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Mol Brain Res. 1992;15:281–290. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90119-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahata R, Matsumura H, Eguchi N, Kantha S, Satoh S, Sakai T, Kondo N, Hayaishi O. Seasonal variation in levels of prostaglandins D2, E2, and F2(α) in the brain of a mammalian hibernator, the Asian chipmunk. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1996;54:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(96)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takamatsu N, Kojima M, Taniyama M, Ohba K, Uematsu T, Segawa C, Tsutou S, Watanabe M, Kondo J, Kondo N, Shiba T. Expression of multiple a1-antitripsin-like genes in hibernating species of the squirrel family. Gene. 1997;204:127–132. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trachsel L, Edgar D, Heller HC. Are ground squirrels sleep deprived during hibernation? Am J Physiol. 1991;29:R1123–R1129. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.6.R1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Urade Y, Kitahama K, Ohishi H, Kaneko T, Mizuno N, Hayaishi O. Dominant expression of mRNA for prostaglandin D synthase in leptomeninges, choroid plexus, and oligodendrocytes of the adult rat brian. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9070–9074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker JM, Glotzbach SF, Berger RJ, Heller HC. Sleep and hibernation in ground squirrels (Citellus spp): electrophysiological observations. Am J Physiol. 1977;223:R213–R221. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1977.233.5.R213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang LCH. Is endogenous opiod involved in hibernation? In: Carey C, Florant G, Wunder B, Horwitz B, editors. Life in the cold. Westview; Boulder, CO: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson BE, Deeb S, Florant GL. Seasonal changes in hormone-sensitive and lipoprotein lipase mRNA concentrations in marmot white adipose tissue. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:R177–R181. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.2.R177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]