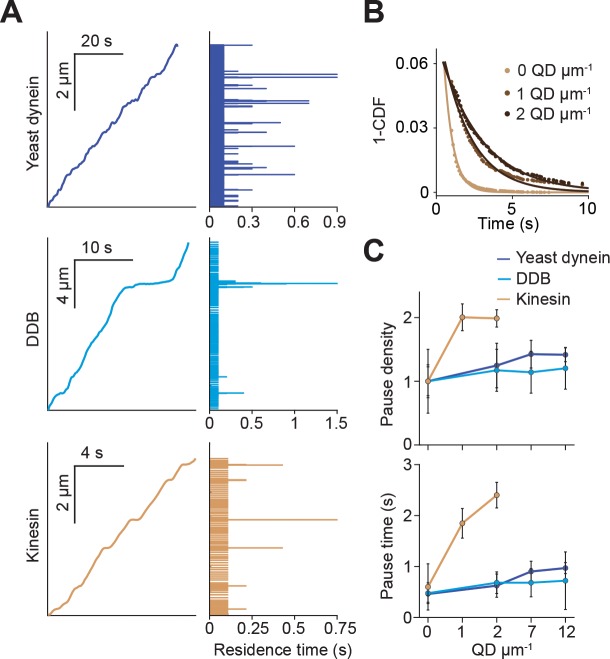

Figure 2. Kinesin pauses more frequently than dynein when encountering QD obstacles.

(A) (Left) Representative traces of yeast dynein, DDB, and kinesin in the absence of QD obstacles on surface-immobilized MTs. (Right) Residence times of the motors in each section of the traces. (B) The inverse cumulative distribution (1-CDF) of kinesin residence times at different obstacle concentrations were fit to a single exponential decay. The residuals of that fit (shown here) are fit to a single exponential decay (solid line) to calculate the density and duration of kinesin pausing. (C) Density and duration of the pauses of the three motors. Pause densities (pauses/µm) are normalized to the 0 QDs µm−1 condition. Kinesin pausing behavior at 7 and 12 QDs µm−1 could not be determined because the motor was nearly immobile under these conditions. From left to right, n = 535, 520, 158, 29 for yeast dynein, 511, 449, 391, 276 for DDB, and 570, 127, 112 for kinesin. Error bars represent SEM calculated from single exponential fit to residence times.