Abstract

Objective:

We aimed to describe interactions between police and persons who experience homelessness and serious mental illness and explore whether housing status is associated with police interactions.

Method:

We conducted a secondary analysis of 2008 to 2013 data from the Toronto, Canada, site of the At Home/Chez Soi study. Using police administrative data, we calculated the number and types of police interactions, the proportion of charges for acts of living and administration of justice, and the proportion of occurrences due to victimization, involuntary psychiatric assessment, and suicidal behavior. Using generalized estimating equations, we estimated the odds of police interaction by housing status.

Results:

This study included 547 adults with mental illness who were homeless at baseline. In the year prior to randomization, 55.8% of participants interacted with police, while 51.7% and 43.0% interacted with police in Study Years 1 and 2, respectively. Of 2,228 charges against participants, 12.6% were due to acts of living and 21.2% were for administration of justice. Of 518 occurrences, 41.1% were for victimization, 45.6% were for mental health assessment, and 22.2% were for suicidal behavior. The odds of any police interaction during the past 90 days was 47% higher for those who were homeless compared to those who were stably housed (95% CI 1.26 to 1.73).

Conclusions:

For people who experience homelessness and mental illness in Toronto, Canada, interactions with police are common. The provision of stable housing and changes in policy and practice could decrease harms and increase health benefits associated with police interactions for this population.

Keywords: homeless persons, homelessness, police, mental health, victimization, crime

Abstract

Objectif:

Nous voulions décrire les interactions entre la police et les personnes en situation d’itinérance et de maladie mentale grave, et explorer si le statut du logement est associé aux interactions de la police.

Méthode:

Nous avons mené une analyse secondaire des données de 2008-2013 du site de l’étude At Home/Chez Soi de Toronto, Canada. À l’aide des données administratives de la police, nous avons calculé le nombre et les types d’interactions policières, la proportion des accusations liées au style de vie et à l’administration de la justice, et la proportion des incidents attribuables à la victimisation, à l’évaluation psychiatrique involontaire et au comportement suicidaire. Au moyen d’équations d’estimation généralisées, nous avons estimé les probabilités d’interactions policières selon le statut du logement.

Résultats:

Cette étude comprenait 547 adultes souffrant de maladie mentale qui étaient sans abri au départ. Dans l’année précédant la randomisation, 55,8% des participants ont interagi avec la police, tandis que 51,7% et 43,0% ont interagi avec la police durant les années 1 et 2 de l’étude, respectivement. Sur les 2 228 accusations portées contre les participants, 12,6% étaient au motif du style de vie et 21,2% pour l’administration de la justice. Sur 518 incidents, 41,1% étaient attribuables à la victimisation, 45,6% à l’évaluation de la santé mentale, et 22,2% au comportement suicidaire. Les probabilités d’une interaction policière durant les 90 jours précédents étaient 47% plus élevées pour ceux qui étaient sans abri comparativement à ceux qui étaient logés de façon stable (IC à 95% 1,26 à 1,73).

Conclusions:

Pour les personnes qui vivent une situation d’itinérance et de maladie mentale à Toronto, Canada, les interactions avec la police sont courantes. L’offre de logement stable et des changements de politiques et de pratique pourraient réduire les méfaits et accroître les bénéfices pour la santé associés aux interactions policières pour cette population.

Introduction

People experiencing homelessness and mental illness often have complex care needs and may face substantial barriers to accessing social and health services. Challenging life circumstances, substance use, morbidity, and unwillingness to engage with offered services are individual-level factors that affect access to social and health services.1,2 Structural-level factors include the lack of health insurance coverage, prejudice and discrimination of service providers, lack of appropriate services, and a lack of coordination and collaboration between mental health, social welfare, and homeless services.1,2

This population experiences substantial criminal justice system involvement. A recent systematic review of data for homeless persons with serious mental illness found lifetime prevalence rates of between 62.9% and 90.0% for arrest, between 28.1% and 80.0% for conviction of a crime, and between 48.0% and 67.0% for imprisonment.3 Police interactions may be indicated and appropriate to meet the needs of this population, for example, to respond to victimization or to support access to mental health care and to address public safety issues, given the increasing role of the police in addressing crises in the community.4 However, police interactions may also reflect the “criminalization of homelessness,”5 which refers to the development and enforcement of laws that restrict activities that are “common to homeless people in public places”6 including “acts of living” such as sleeping, eating, sitting, or panhandling in public spaces,7 or use of alcohol, as well as the criminalization of mental illness,8 in which “disturbing behavior” or “troublesome situations” associated with mental illness are treated as criminal behavior4 in the context of deinstitutionalization.8

Interactions with police may positively or negatively impact the health of people who are homeless and mentally ill. Negative impacts may include physical and emotional trauma, anxiety, and a worsening perspective regarding police fairness and trustworthiness,9,10 which may affect future willingness to seek aid from police.10 Further, as police have access to data regarding prior police contacts, documented interactions with police may affect the likelihood and outcome of subsequent interactions. Positive individual- and community-level impacts of interactions may include facilitated access to indicated health or social services,11,12 better public safety and feelings of security,9 and stronger relations between police and individuals and communities.9

In this study, we aimed to describe the number and types of interactions with police for homeless persons with mental illness in Toronto, Canada, who participated in the At Home/Chez Soi trial. We explored interactions that indicate the criminalization of homelessness and the association between housing status and police interaction for this population.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a secondary analysis of data collected prospectively in the At Home/Chez Soi study. The At Home/Chez Soi study was a randomized trial that compared the Housing First approach with existing community approaches at five sites across Canada. Participants were recruited from October 2009 to July 2011 and followed for 2 years after randomization. Study inclusion criteria were age 18 or older, absolutely homeless or precariously housed, having a confirmed major mental disorder, and not currently being served by an assertive community treatment or intensive case management program.13,14 A more detailed description of recruitment and exclusions at randomization has been reported previously.14–16 Participants were randomized to intervention or treatment as usual groups; the intervention included scattered-site housing using rent supplements and intensive case management services or assertive community treatment based on psychiatric illness severity, while the usual care group had access to the existing housing and support services in the their communities.14 For the purpose of this study, we used only the data from Toronto site participants (N = 575) who consented (n = 547, 95%) to accessing their data from the Toronto Police Service.13

Data Sources

Housing history was evaluated every 3 months during the study’s 2 year follow-up with the Residential Timeline Follow-Back Questionnaire,17 which recorded details such as move in and move out dates for each type of residence: street, unstable housing, stable housing, emergency/crisis, and institution. Stable housing was defined as when participants were expected to remain in the same housing for at least 6 months or had tenancy rights. We split each participant’s housing history into consecutive 90-day intervals from 90 days prior to randomization to 2 years after randomization. We categorized housing status as housed (stably housed on 100% of days), partly housed (stably housed on >0% to <100% of days), and not housed (0% of days stably housed) based on non-missing housing history data within each interval. Only 512 (94%) of the 547 consenting participants had available housing history data.

Toronto Police Service data were available for 1 year prior to randomization and 2 years after randomization for each participant. Toronto Police Service data were classified into four categories: contacts from the Master Names Index and Field Information Report databases, occurrences from the Enterprise Case and Occurrence Processing System, charges from the Criminal Information Processing System, and tickets from the POT system. A contact is an interaction between police and a community member for criminal or noncriminal reasons or for general investigations, which are documented in police contact cards. An occurrence, or written report, documents an unusual problem, incident, deviation from standard practice, or situation that requires follow-up action.18 A charge occurs when the police charge a person whom they believe has violated the Criminal Code of Canada. A ticket is a notice of a violation against the Criminal Code of Canada or other federal statute, provincial act, or municipal bylaw18 and typically provides the recipient with options for how to proceed, for example, plead guilty and pay the specified fine or ask for a trial date. A single incident could be captured in one or more of these categories, for example, an incident could be documented as a contact, as an occurrence if it required follow-up action, as a charge if charges were laid, and as a ticket if a ticket was also issued.

Outcomes

Our primary study outcome was whether the participant had any days with police interaction during the period under study. We defined a police interaction as a contact, occurrence, charge, or ticket.

Regarding reasons for police interaction, there were 32 unique reasons provided for contacts. We combined three categories related to bail into a single category, and we presented data for all reasons with over 20 contacts. We categorized the remaining reasons for contacts into a missing/other category. We maintained the categories provided for reasons for tickets. As there were more than 200 reasons for charges provided, we classified charges into the following categories: activities of living (defined as smoking, use of alcohol or intoxication in public or in a form that was not liquor, fouling of a city street, indecent acts, or soliciting), administration of justice (defined as offenses against the administration of justice such as failure to appear in court or comply with the conditions of a probation order), nonviolent crime (including property crimes, fraud, drug-related crimes, and prostitution), violent crime (including assault, threat of injury, and homicide), and missing/other. Given our interest in experiences of victimization and severe mental illness in this population, we categorized occurrences as related to victimization if the reason specified that the person was the victim or reportee, related to mental health assessment if a relevant provincial mental health act was specified, and related to attempting or threatening suicide. As some persons were taken for a mental health assessment because of suicidal behavior or had victimization experiences and suicidal behavior, these categories were not mutually exclusive.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnic/racial identity, education), duration of homelessness, disability (measured with the Multnomah Community Ability Scale), and mental health status (identified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, criteria in the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview 6.0).

For three consecutive yearly intervals, 1 year prior to randomization and the first and second years after randomization, we calculated descriptive statistics on the prevalence and number of days with any police interaction as well as the prevalence and number of days with contacts, occurrences, charges, and tickets, respectively. We presented descriptive statistics based on days given that, as noted, a single incident may be captured in more than one of the interaction types.

To estimate the association between housing status and police interaction, we fitted an unadjusted logistic generalized estimating equation (GEE) model for any police interaction as well as separate GEE models for each of contacts, occurrences, charges, and tickets. Each GEE model was fitted with an exchangeable correlation structure to account for repeated measures of housing history from the same participant over time. For each participant, we modeled whether the relevant type of police interaction occurred within each 90-day interval from 90 days prior to randomization to 2 years after randomization, which we chose as the follow-up period to include all available data. The participant’s housing status during the 90-day interval was the time-varying covariate of interest. We did not adjust for other covariates since we were interested in the overall association between housing status and police interaction rather than in specific mechanisms of association. We removed intervals with half or more (i.e., 45 or more) days of the housing history missing, which represented 3.6% of the data, as it would be difficult to properly determine their housing status with limited data. We presented the estimated odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and the risk of police interaction by housing status for each GEE model. A sensitivity analysis performed by fitting the model using all data yielded similar results.

For each type of police interaction, we described the number and rate of interactions by reason for interaction, stratified by housing status in each 90-day interval, as described above. All statistical analyses were performed in R (Version 3.5.0).

Results

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and health status characteristics of study participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants in the At Home/Chez Soi Study Toronto Site.

| Characteristics | ||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 40.3 (11.7) | |

| Gender, N (%) | Female | 160 (29.3) |

| Male | 377 (68.9) | |

| Trans | 10 (1.8) | |

| Ethnic or cultural identity, N (%) | White | 200 (36.6) |

| Aboriginal | 26 (4.8) | |

| Other ethnoracial | 321 (58.7) | |

| Education, N (%) | Did not complete high school | 266 (48.6) |

| Completed high school | 101 (18.5) | |

| Some postsecondary school | 178 (32.5) | |

| Lifetime duration of homelessness, years, median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0 to 7.0) | |

| MCAS score, mean (SD) | 61.6 (6.8) | |

| MINI diagnostic categories, N (%) | Depressive episode | 194 (35.5) |

| Manic or hypomania episode | 57 (10.4) | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 126 (23.0) | |

| Mood disorder with psychotic features | 115 (21.0) | |

| Psychotic disorder | 203 (37.1) | |

| Substance dependence or abuse | 257 (47.0) | |

| Alcohol dependence | 162 (29.6) | |

| Alcohol abuse | 75 (13.7) | |

| Substance dependence | 207 (37.8) | |

| Substance abuse | 52 (9.5) | |

Note. N = 547. MCAS = Multnomah Community Ability Scale; MINI4 = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

As shown in Table 2, a high proportion of participants interacted with police in each year: 55.8% in the year prior to randomization, 51.7% in Study Year 1, and 43.0% in Study Year 2. Most persons with any police interaction had multiple interactions per year, with a median number of days of interaction of 4 (interquartile range [IQR] 2 to 8) in the year prior to randomization, 3 (IQR 1 to 8) in Study Year 1, and 3 (IQR 2 to 8) in Study Year 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Police Interaction and Number of Days with Police Interaction Per Year During 1 Year Prior to Randomization and 2 Years Postrandomization for Participants in the At Home/Chez Soi Study Toronto Site.

| Police Interaction | 1 Year Prior to Randomization | Study Year 1 | Study Year 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any, % | For Those with Any | Any, % | For Those with Any | Any, % | For Those with Any | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||||

| Any | 55.8 | 7.7 (11.5) | 4 (2 to 8) | 51.7 | 7.1 (10.1) | 3 (1 to 8) | 43.0 | 6.7 (9.4) | 3 (2 to 8) |

| Contacts | 47.7 | 6.6 (10.6) | 3 (1 to 6) | 43.7 | 6.3 (9.2) | 3 (1 to 7) | 36.8 | 5.8 (8.6) | 3 (1 to 7) |

| Occurrences | 16.6 | 1.9 (1.5) | 1 (1 to 2) | 17.0 | 1.6 (1.2) | 1 (1 to 2) | 14.4 | 1.5 (1.1) | 1 (1 to 2) |

| Charges | 34.2 | 2.7 (2.4) | 2 (1 to 3) | 27.4 | 2.6 (2.5) | 2 (1 to 3) | 21.9 | 2.5 (2.2) | 2 (1 to 4) |

| Tickets | 11.2 | 4.3 (5.4) | 2 (1 to 4) | 10.6 | 4.2 (4.8) | 2 (1 to 5.8) | 7.9 | 4.1 (4.7) | 2 (1 to 4.5) |

Note. N = 547. IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

During the period from 1 year prior to randomization to 2 years postrandomization, the 547 participants accrued 4,734 contacts, 518 occurrences, 2,228 charges, and 1,161 tickets. Of 518 occurrences, 213 (41.1%) were related to victimization, 236 (45.6%) were related to mental health assessment under the provincial mental health act, and 115 (22.2%) were related to threatened or attempted suicide (Supplemental Material 1). Of 2,228 charges, 281 (12.6%) were related to acts of living, and 472 (21.2%) were related to the administration of justice.

From the GEE models, persons who were not housed or who were partly housed in the previous 90 days had significantly higher odds of having any police interaction than persons who were housed in the previous 90 days. The OR for any police interaction was 1.47 (95% CI, 1.26 to 1.73) for intervals when not housed compared to housed, corresponding to risks of 33.2% and 25.2%, and 1.32 (95% CI, 1.12 to 1.56) for intervals when partly housed compared to housed, corresponding to risks of 30.8% and 25.2% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds Ratios for the Association between Housing Status and Police Interaction in the At Home/Chez Soi Study Toronto Site.

| Housing Status | Any | Contacts | Occurrences | Charges | Tickets | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | Risk (%)a | OR (95% CI) | Risk (%)a | OR (95% CI) | Risk (%)a | OR (95% CI) | Risk (%)a | OR (95% CI) | Risk (%)a | |

| Not housed, n = 1,607b | 1.47 (1.26 to 1.73) | 33.2 | 1.46 (1.22 to 1.74) | 26.8 | 1.32 (0.95 to 1.84) | 5.9 | 1.70 (1.33 to 2.18) | 14.5 | 1.65 (1.17 to 2.34) | 5.7 |

| Partly housed, n = 700b | 1.32 (1.12 to 1.56) | 30.8 | 1.24 (1.04 to 1.48) | 23.8 | 1.68 (1.19 to 2.37) | 7.4 | 1.58 (1.25 to 2.00) | 13.6 | 1.12 (0.75 to 1.67) | 3.9 |

| Housed, n = 1,811b | ref | 25.2 | ref | 20.1 | ref | 4.6 | ref | 9.1 | ref | 3.5 |

Note. N = 512. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; GEE = generalized estimating equation.

aRisk, ORs, and 95% CIs were calculated from GEE models.

b n refers to the total number of observations contributed by the repeatedly measured housing and police interaction status of participants. Each participant could contribute a maximum of nine observations based on the number of 90-day intervals for which housing history data were available. We classified housing status as housed if stably housed on 100% of days, partly housed if stably housed on >0% to <100% of days, and not housed if stably housed on 0% of days in each interval.

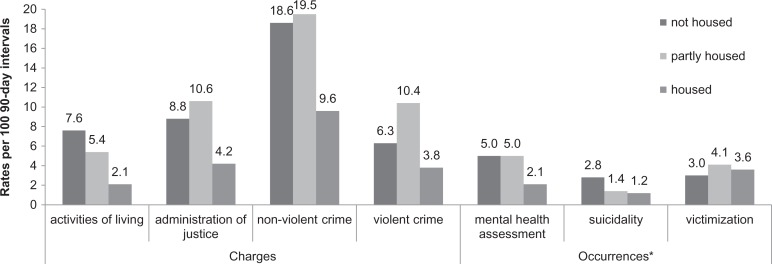

For most reasons for police interactions, the rates were higher for persons who were not housed and who were partly housed compared to those who were housed (Supplemental Material 1). In particular, the rates of charges for activities of daily living and administration of justice were over twice as high in periods when people were not housed and were partly housed, respectively, compared to when people were housed (Figure 1). In contrast, occurrences for victimization were higher during intervals when people were housed compared to not housed.

Figure 1.

Rates of police charges and police occurrences for selected reasons for people in the At Home/Chez Soi study Toronto site, N = 512, by housing status per 90-day interval. Housing status for each participant per 90-day interval over the study period for which housing history data were available. We classified housing status as housed if stably housed on 100% of days, partly housed if stably housed on >0% to <100% of days, and not housed if stably housed on 0% of days in each interval. There were 1,607 not housed intervals, 700 partly housed intervals, and 1,811 housed intervals. *These categories are not mutually exclusive.

Discussion

In this study of adults with homelessness and mental illness, police interactions were common. Over half of participants interacted with police in the year prior to study enrolment and in the year after randomization, respectively, and 43.0% interacted with police in the second year after randomization. Over the study period, between one in five and one in three participants had charges laid each year. About one in five charges was for the administration of justice and almost one in eight charges was for an act of living, and there was a large number of occurrences due to victimization, for mental health assessment, and for threatening or attempting suicide. The risk of police interaction was significantly lower during periods when individuals were housed compared to periods when they were not housed or partly housed. The rates of police charges were substantially higher in intervals in which people were not housed or partly housed compared to when housed, which may indicate the criminalization of homelessness in Toronto.

Other Canadian studies have also identified that people with mental illness are more likely to have interactions with police, compared to the general population.11,19 National data from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey–Mental Health, which did not include homeless persons, revealed that 34.4% of persons with a mental or substance use disorder reported police contact in the past year, compared with 16.7% of those who did not have a mental or substance use disorder.19 In our study of people who experience mental illness and homelessness, the proportions were even higher, at 55.8%, 51.7%, and 43.0%, respectively, with police interactions each year. Similarly, we identified a higher rate of police interactions than did a 2009 to 2011 study of people with mental illness in British Columbia.11 Studies from other countries similarly reveal that persons with mental disorders20 and persons who are homeless have frequent contact with police.21,22

Our study showed that persons with mental illness were more likely to have police interactions if they were not housed or partly housed compared to if they were housed. If mental illness and homelessness each independently increase the risk of police interaction, persons who experience both mental illness and homelessness may face a synergistically increased risk of police interaction. Certainly, the high prevalence of police interaction during the year prior to randomization period (when all participants were homeless leading up to joining the study) of 55.8% and the risk per 90-day interval for persons not housed of 33.2% (compared to 25.2% for persons who were housed) suggest that the risk level is highest for persons with mental illness while they are homeless.

Our study has several potential limitations. Since not every police interaction is documented, the estimates of police interaction likely underestimate true interactions, and further, these data would not capture all relevant events that could lead to police interactions, such as perpetrating or experiencing violence. We do not have detailed information regarding each interaction, and specifically, we lack data on the experiences of study participants with police including the impact of interactions on health; further research specific to the experiences of homeless persons with mental illness with police would be valuable, including qualitative work. Consistent with our study objectives, we did not examine the effect of randomized group on police interactions. Since we included data on housing status in the 2 years postrandomization as well as the year prior to randomization, however, periods housed may also represent periods when participants received other services through the study, and some of the association between housing status and risk of police interaction may therefore be attributable to services received through the intervention other than housing. We did not statistically compare the rates of police interaction for specific reasons by housing status; we considered this analysis exploratory, as for many reasons for interactions, we would not have had adequate power to compare across groups.

The study also has several strengths. While other studies have described reasons for arrest for people with mental illness23 and data on lifetime and past year criminal justice system involvement for people with mental illness and homelessness,3 this is the first study to define the rates and reasons for police interactions in people who experience homelessness and mental illness, including by housing status. These data are important for understanding the potential value of interventions such as access to mental health care, diversion programs, and housing. In addition, rather than relying on self-report, we used health administrative data to identify police interactions, which may be more sensitive.

We found evidence that police play multiple roles in the lives of people who experience homelessness and mental illness in Toronto and that being housed is associated with lower rates of police interaction. These findings have important implications. First, the association between housing status and police interactions suggests that the provision of housing may reduce police interaction for people who have mental illness, including criminal charges. Further research is indicated to define the impact of intervening to provide housing on police interaction. Second, the substantial number of charges due to acts of living suggests that people who experience homelessness and mental illness may experience unnecessary police interactions, especially during periods when not housed. As these interactions may negatively impact health,9,10 lead to greater criminal justice system involvement, and worsen attitudes toward police,10,11,21 consideration should be given to changes in policy and practice to prevent such interactions. Third, it may be challenging for this population to comply with rigid conditions of probation or to other aspects of the administration of justice such as court appearances, and initiatives should be considered to modify such requirements without compromising public safety and to better support people in meeting conditions. Fourth, given the high number of occurrences related to required mental health assessment, police officers need access to ongoing mental health training and partnerships with interdisciplinary crisis teams.11,21,24–26 Fifth, frequent police interactions may offer opportunities to positively impact health, for example, for police to link people with housing or temporary shelter and to facilitate access to health care and social services.8 Resources should be put in place to support police in these roles,26 and limited evidence from other jurisdictions suggests that police may be interested in pursuing this work.6

Conclusions

In this study, police interactions were common for people who experienced homelessness and mental illness in Toronto, Canada. We found that in periods when people were housed, the risk of police interaction was significantly lower compared to periods when homeless some or all of the time. These findings support the need for interventions including the provision of stable housing as well as policy reform and police training to prevent unnecessary and potentially harmful interactions with police for this population.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, Supplementary_material_861386 for Interactions between Police and Persons Who Experience Homelessness and Mental Illness in Toronto, Canada: Findings from a Prospective Study by Fiona G. Kouyoumdjian, Ri Wang, Cilia Mejia-Lancheros, Akwasi Owusu-Bempah, Rosane Nisenbaum, Patricia O’Campo, Vicky Stergiopoulos and Stephen W. Hwang in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the At Home/Chez Soi participants whose willingness to share their lives, experiences, and stories with us made this project possible. We also thank the At Home/Chez Soi project team, site coordinators, and service providers who have contributed to the design, implementation, and follow-up of the project at the Toronto site. We thank the Toronto Police Service for providing us with access to data regarding police interactions.

Authors’ Note: The funders had no role in the analysis and interpretation of the data and the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. The views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of any of the funders.

Data Access: The At Home/Chez Soi project has a process by which interested investigators who would like to use the data can make a formal request. The formal request is reviewed by a cross-site committee, which will consider approval and data sharing, in consideration of agreements in place with relevant organizations such as the Toronto Police Service.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a financial contribution from Health Canada to the Mental Health Commission of Canada and by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

ORCID iD: Fiona G. Kouyoumdjian, MD, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6869-7516

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6869-7516

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Canavan R, Barry MM, Matanov A, et al. Service provision and barriers to care for homeless people with mental health problems across 14 European capital cities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Salize HJ, Werner A, Jacke CO. Service provision for mentally disordered homeless people. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(4):355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roy L, Crocker AG, Nicholls TL, Latimer EA, Ayllon AR. Criminal behavior and victimization among homeless individuals with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(6):739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Markowitz FE. Mental illness, crime, and violence: risk, context, and social control. Aggress Violent Behav. 2011;16(1):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ben-Moshe L. Why prisons are not “The New Asylums”. Punishm Soc. 2017;19(3):272–289. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robinson T. No right to rest: police enforcement patterns and quality of life consequences of the criminalization of homelessness. Urban Affairs Review. 2017;55(1):1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7. United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. Searching out solutions: constructive alternatives to the criminalization of homelessness. Washington (DC): United States Interagency Council on Homelessness; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fisher WH, Silver E, Wolff N. Beyond criminalization: toward a criminologically informed framework for mental health policy and services research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33(5):544–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Geller A, Fagan J, Tyler T, Link BG. Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2321–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zakrison TL, Hamel PA, Hwang SW. Homeless people’s trust and interactions with police and paramedics. J Urban Health. 2004;81(4):596–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brink J, Livingston J, Desmarais S, et al. A study of how people with mental illness perceive and interact with the police. 2011. [cited May 2018] Available from: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/Law_How_People_with_Mental_Illness_Perceive_Interact_Police_Study_ENG_1_0_1.pdf.

- 12. Schiff DM, Drainoni ML, Weinstein ZM, Chan L, Bair-Merritt M, Rosenbloom D. A police-led addiction treatment referral program in Gloucester, MA: implementation and participants’ experiences. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;82:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O’Campo P, Stergiopoulos V, Nir P, et al. How did a Housing First intervention improve health and social outcomes among homeless adults with mental illness in Toronto? Two-year outcomes from a randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e010581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goering PN, Streiner DL, Adair C, et al. The At Home/Chez Soi trial protocol: a pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a Housing First intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stergiopoulos V, Hwang SW, Gozdzik A, et al. Effect of scattered-site housing using rent supplements and intensive case management on housing stability among homeless adults with mental illness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2015;313(9):905–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aubry T, Goering P, Veldhuizen S, et al. A multiple-city RCT of housing first with assertive community treatment for homeless Canadians with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(3):275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsemberis S, McHugo G, Williams V, Hanrahan P, Stefancic A. Measuring homelessness and residential stability: the residential time-line follow-back inventory. J Community Psychol. 2006;35(1):29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toronto Police Service. Toronto Police Service Public Safety Data Portal: Data Definitions and Counting Methodology. 2017. [cited May 13, 2018] Available from: http://data.torontopolice.on.ca/pages/glossary.

- 19. Boyce J, Rotenberg C, Karam M. Mental health and contact with police in Canada, 2012. Ottawa (ON): Juristat, Statistics Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Livingston JD. Contact between police and people with mental disorders: a review of rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(8):850–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McNamara RH, Crawford C, Burns R. Policing the homeless: policy, practice, and perceptions. Policing. 2013;36(2):357–374. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berk R, MacDonald J. Policing the homeless: an evaluation of efforts to reduce homeless-related crime. Criminol Public Pol. 2010;9(4):813–840. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fisher WH, Roy-Bujnowski KM, Grudzinskas AJ, Jr, Clayfield JC, Banks SM, Wolff N. Patterns and prevalence of arrest in a statewide cohort of mental health care consumers. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(11):1623–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hirschtritt ME, Binder RL. Interrupting the mental illness-incarceration-recidivism cycle. JAMA. 2017;317(7):695–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoffman R, Putnam L. “Not Just Another Call…Police Response to People with Mental Illnesses in Ontario:” A practical guideline for the frontline officer. Toronto (ON): Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iacobucci F. Police encounters with people in crisis: An independent review conducted by The Honourable Frank Iacobucci for Chief of Police William Blair, Toronto Police Service, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, Supplementary_material_861386 for Interactions between Police and Persons Who Experience Homelessness and Mental Illness in Toronto, Canada: Findings from a Prospective Study by Fiona G. Kouyoumdjian, Ri Wang, Cilia Mejia-Lancheros, Akwasi Owusu-Bempah, Rosane Nisenbaum, Patricia O’Campo, Vicky Stergiopoulos and Stephen W. Hwang in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry