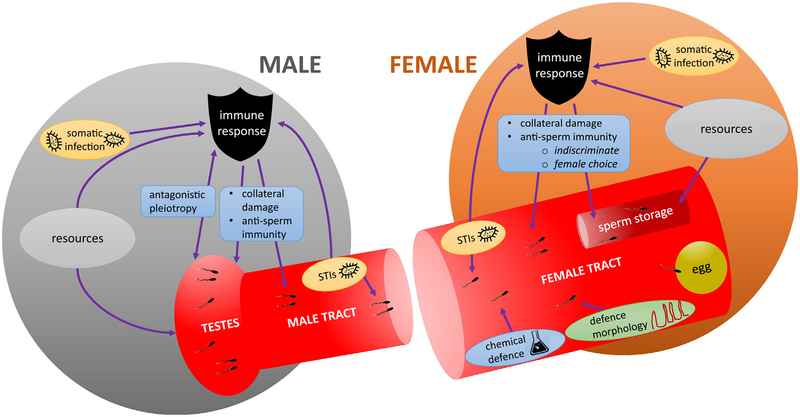

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the interplay between immunity and sperm success in males and females. Resources may trade-off between the immune system and the production of sperm in males, and the protection of sperm in storage in females, leading to sub-maximal trait values. Trade-offs could also come about genetically: genes of shared male immune and sperm-related function could generate antagonistic pleiotropy, preventing simultaneous maximization of both traits. STIs can harm sperm directly, and thus immune defense against STIs could protect sperm. However, immune responses to STIs or somatic infections could also harm sperm as a side-effect of their defensive actions, causing collateral damage to sperm. Immune responses may negatively impact sperm directly, particularly in vertebrates via anti-sperm antibodies, both in females, and in males as an auto-immune response. Female immune responses may indiscriminately harm sperm, which could contribute to infertility, or they may form part of adaptive female choice, selecting out the sperm of disfavored males after mating, but before fertilization. Within the female reproductive tract sperm interact with the chemical and morphological environment—which is likely be designed to inhibit pathogen proliferation, and may help or hinder the sperm—on the way to sperm storage sites and fertilization.