Abstract

Despite advances in global mental health evidence and policy recommendations, the uptake of evidence-based practices (EBP) in low- and middle-income countries has been slow. Lower resource settings have several challenges, such as limited trained personnel, lack of government resources set aside for mental health, poorly developed mental health systems, and inadequate child protection services. Given these inherent challenges, a possible barrier to implementation of EBP is how to handle safety risks such as suicide, intimate partner violence (IPV), and/or abuse. Safety issues are prevalent in populations with mental health problems and often over-looked and/or underreported. This article briefly reviews common safety issues such as suicide, IPV, and child abuse and proposes the use of certain implementation strategies which could be helpful in creating locally appropriate safety protocols. This article lays out steps and examples of how to create a safety protocol and describes and presents data on safety cases from three different studies. Discussion includes specific challenges and future directions, focusing on implementation.

Global mental health has seen significant advances over the past decade. Researchers have validated assessment tools creating evidence-based measures for use in several low- and middle-income countries (LMIC; e.g., Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba, & Bolton, 2008; Jordans, Komproe, Tol, & De Jong, 2009; Kohrt et al., 2011; Murray et al., 2011a). The effectiveness and feasibility of implementing evidence-based treatments (EBT) for mental health problems in LMIC have been shown through multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs), including cognitive-behavioral interventions for depression in primary health care (Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts, & Creed, 2008), Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression for adults and adolescents (IPT & IPT-A; Bolton et al., 2003; Patel et al., 2010; Bolton et al., 2007), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Bass et al., 2013), and a common elements treatment approach for multiple common mental health problems (Bolton et al., 2014; Murray et al., 2013). The research evidence has resulted in the World Health Organization (WHO) recommending EBT in their Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP; WHO, 2010). However, despite research evidence and policy recommendations, the uptake of EBT in LMIC is low. Although the sluggish uptake of EBT is not unique to LMIC or mental health (e.g., Proctor et al., 2009; Rudan, El Arifeen, Black, & Campbell, 2007), it is important to identify barriers and possible ways to facilitate their implementation.

The implementation of mental health interventions in LMIC is wrought with challenges, such as limited trained personnel and turnover, lack of government resources set aside for mental health, poorly developed mental health systems, and inadequate child protection services (Patel, 2009; Saxena, Thornicroft, Knapp, & Whiteford, 2007). One result of these challenges is that service providers may not be equipped to adequately respond to suicidal ideation or behaviors, domestic or intimate partner violence, and/or child abuse. Few clinical domains are as programmatically, clinically, and emotionally challenging as managing suicide, intimate partner violence, and child abuse. These “safety” challenges may deter organizations from including mental health services in their packages of care, thus serving as a significant barrier to uptake of evidence-based mental health assessments and treatments. Practical strategies to address serious safety issues in LMIC are a current gap in the literature as well as a barrier to implementation. This article will provide example strategies for developing local safety protocols in LMIC which could assist with the management, and hopefully prevention, of suicide, intimate partner violence, and abuse/ neglect.

Overview of Safety Issues: Suicide, Intimate Partner Violence, and Child Abuse

Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors

The WHO (2014) estimates that more than 1 million people die by suicide annually worldwide. However, this may be an underestimate because recent national estimates of the prevalence and risk factors for suicide are unavailable in many countries, particularly LMIC. In the chain of events leading to suicidal behaviors, the most common is mental health problems. Most suicide research has been conducted in developed countries, where studies have consistently shown that mental illness is present in 90% of suicides and serious suicide attempters (Beautrais et al., 1996; Cavanagh, Carson, Sharpe, & Lawrie, 2003). Nock et al. (2008), from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative, reported that in high-income countries (HIC), the strongest diagnostic risk factors for suicide attempt were mood disorders, but impulse control disorders (intermittent explosive, attention-deficit/hyperactivity, conduct, and oppositional defiant disorders) were more predictive in LMIC. Also, often in this chain of events are facilitating factors such as the tendency to be impulsive or a state of intoxication, stressful life events, living in a culture in which social taboo regarding suicide is weak, the absence of others around to stop the suicide attempt, and finally, the ready availability of lethal means. Evidence-based effective suicide prevention efforts suggested within HIC include physician education in depression recognition and treatment and restricting access to lethal methods (Mann et al., 2005; Shaffer & Craft, 1999). Many suicide prevention approaches commonly used in HIC are not feasible in LMIC, which lack resources, have poorly established primary and mental health service systems, and have weak political processes (Khan, 2005). An important early step in managing suicidal ideation is to ask patients directly whether they are suicidal. Other practical, feasible, and engaging clinical management strategies, which could be used in LMIC, include the creation of safety plans and hope boxes. Hope boxes contain mementos, objects, photos, letters, and others alike, all of which encourage a sense of hope and provide reasons for living (Joiner & Ribeiro, 2011).

Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is common in the United States, with nearly 31% of women and 26% of men reporting experiencing some form in their lifetime (Black et al., 2011). These estimates are not considered representative because of underreporting, leaving many cases undetected (Moyer et al., 2013). At the turn of the century, it was estimated that, globally, one in three women had been beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused at some point during her lifetime (Heise, Ellsberg, & Gottemoeller, 1999). However, global and national data are very scarce, particularly in LMIC. Sexual violence has been used as a tactic of war in conflicts across the globe, including in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and in the Americas. In the context of humanitarian crises and emergencies, civilian women and children are often the most vulnerable to exploitation, violence, and abuse because of their gender, age, and status in society (WHO, 2005). In addition to the context of war and violence, the WHO’s World Report on Violence and Health (WHO, 2002) identifies that violence perpetrated by husbands or male partners is “one of the most common forms of violence against women” (WHO, 2002, p. 87). This type of violence is harder to identify because it often happens within the home, can be highly stigmatizing to the family, and frequently occurs in contexts where legal systems and cultural norms do not treat any of these actions as a crime. The most severe outcome is death, along with a wide range of additional consequences, such as sexually transmitted diseases, unintended pregnancy, mental health conditions, substance abuse, and suicidal behavior (Letourneau, Holmes, & Chasedunn-Roark, 1999; Campbell, 2002; Golding, 1999). In HIC, recommendations include early detection using screening measures within primary health care as well as other settings (e.g., mental health, substance abuse) and several brief safety-focused interventions (Moyer et al., 2013). In LMIC, the provision of intervention programming for IPV is quite limited, although previous studies have found that effective mental health services can be implemented and show significant positive influence on mental health and functioning among victims of IPV (Bass et al., 2013).

Child Abuse and Neglect

Although prevalence rates vary widely, child abuse and neglect is a global public health problem with epidemiological studies showing higher occurrence rates in LMIC than in HIC (Reza et al., 2009; Stoltenborgh, van Ijzendoorn, Euser, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2011). From population-based studies around the world, about 20% of women and 5%–10% of men reported having been sexually abused as children (Finkelhor, 1994a, 1994b). There has been speculation that the perceived increase in child sexual abuse in sub-Saharan Africa may be linked to the spread of HIV. For example, children may be targeted by sexual predators because they are thought to be less likely to have HIV or even thought to be able to cure HIV or other diseases (Lalor, 2004). A recent study found that more than 90% of orphans or abandoned children from six sites (Cambodia, Cameroon, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, and Tanzania) experienced one or more traumatic events, with most children being physically or sexually abused (Whetten, Ostermann, Whetten, O’Donnell, & Thielman, 2011). There is a wealth of research on both physical and sexual abuse showing that these events are linked to increased risk for physical, behavioral, cognitive, and psychological problems (e.g., Shonkoff & Garner et al., 2012; Stoltenborgh, Bakersmans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, & Alink, 2013; Stoltenborgh et al., 2011; Widom, Czaja, & Dutton, 2008). Research suggests that only a small fraction of victims of child abuse and neglect come to the attention of any child protection services—perhaps none in the many countries with no such services (Finkelhor, Lannen, & Quayle, 2011; Gilbert et al., 2009). Prevention of child abuse and neglect has become a significant focus for organizations such as the WHO (2012) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2012) along with the development of evidence-based interventions to address prevention and treatment (WHO, 2002).

Implementing Safety Planning in LMIC

The literature on dissemination and implementation is exploding, with more and more guidance on how to take evidence-based practices (EBP) to real-world settings (e.g., Brownson, Colditz, & Proctor, 2012). A review by Powell et al. (2012) highlighted implementation strategies which have been used, some of which could be useful in addressing the barrier of implementing safety planning in LMIC. Several of this article’s authors (LKM, SS, JB) have been working with service providers in LMIC settings to develop safety plan strategies, including (a) involving patients/ consumers, family members, and stakeholders; (b) developing education materials specific to safety; (c) conducting training on how to handle safety situations; and (d) providing ongoing consultation regarding the management of safety risk from both an expert and local perspective. The end goal is to develop a locally appropriate safety protocol to go along with a mental health service program that can be implemented by community-based mental health service providers to ultimately protect those in need. The specific safety protocol for each setting will vary depending on access to resources, location, and existing infrastructure. Once a protocol is developed, the service provider puts together a core team that is consulted for each safety issue incident. This team is constantly reevaluating the protocol and referral options and revising the safety protocol as needed. This could be conceptualized as similar to a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle, which is used to gather information, evaluate it, and make appropriate changes in a systematic process (e.g., Langley, Nolan, Nolan, Norman, & Provost, 2009). The use of these implementation strategies is described in the following text.

Involving Stakeholders and the Broader Local Community

Because of the lack of existing infrastructure in many LMIC to adequately respond to the safety issues highlighted earlier, the local community is integral in creating new systems. Community meetings should involve as many local stakeholders and/or organizations that could help with safety issues, including (but not limited to) governmental departments (e.g., Ministry of Health), community leaders (e.g., elders, chiefs), respected religious leaders, existing mental health institutions (e.g., psychiatric hospital staff), police and law enforcement agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and community organizations providing direct services to the population as well as consumers.

At these community meetings, an initial description of safety issues, such as suicide, IPV, and child abuse, will need to be provided because not all participants may be familiar with prevalence rates, risk and protective factors, and the unique challenges in serving individuals affected by these safety issues. Following this, a discussion is held with the community members on their perspective of any local resources that exist for individuals experiencing these safety issues. For example, there may be a local community “house” that is known for taking in children for a short time if they are being abused. A list is generated of existing local resources so that someone may follow up to learn more about them and to ask whether they would be open to being included on a safety resource list. The community members are also engaged in brainstorming for other solutions, such as other local organizations (e.g., churches, NGOs), individuals (e.g., a local chief), and/or professionals (e.g., a psychiatrist or psychology professor based locally) who may become a resource. Again, a resource list is created and items are investigated as possible resources. Some resources are maintained based on their ability to provide service, some are discarded if they are no longer working in the community and/or are not providing services related to the safety issues, and some contacts lead to further solutions. The community members who are brought together as a group of local stakeholders can be expanded as more is discovered about the community.

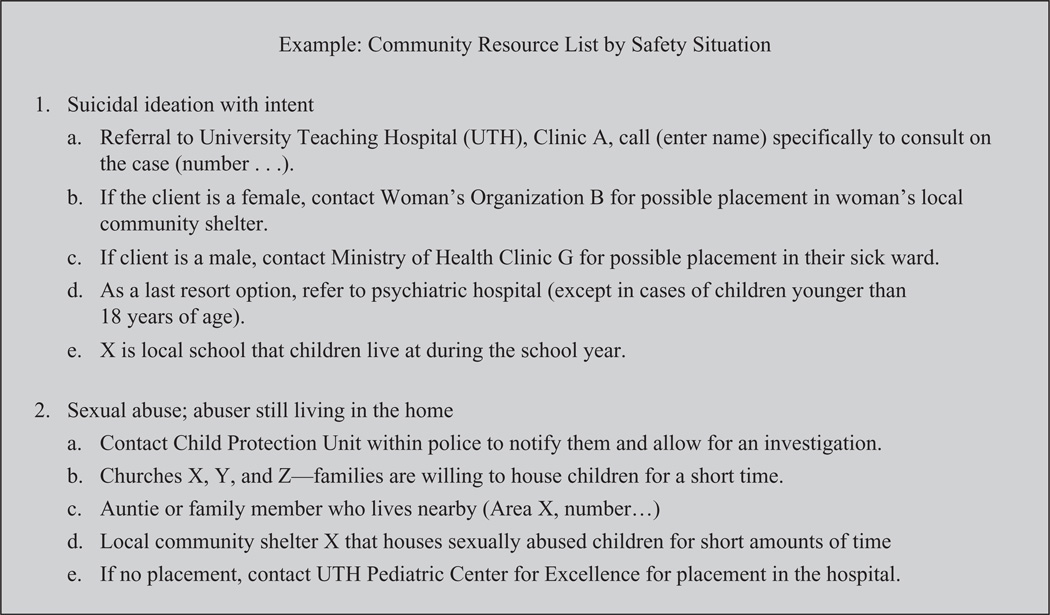

After contact is made with every possible resource, a final list of community resource options for each of the safety concerns is created (see Figure 1 for an example). This list, which augments mental health or psychosocial interventions, will eventually be included in a safety protocol. Involvement of community members and key stakeholders continues throughout the implementation of any safety protocol to assist as challenges and barriers arise to problem solve, adapt the protocol, and help secure further resources. For example, if there has been a dearth of resources for physically abused women, another group meeting might be called to brainstorm additional resources for managing this type of safety concern. This may be formalized as a community advisory board, which is often used in randomized controlled trials.

Figure 1.

Sample community resource list.

Note. To maintain anonymity of local churches, school, and addresses, this example utilizes letters such as “X” to be placeholders for these actual names.

Stakeholder and community involvement is an implementation strategy that provides access to the structures, systems, and personnel which currently exist in the community and allows for maximum use and benefit of safety protocols. The process of working with community members and stakeholders informs the safety protocol, strengthens communication and coordination of care among providers, aids in the creation of a referral network, and creates ownership of the local protocol. Buy-in from key stakeholders is also vital to the acceptability and sustainability of the safety protocol. For example, suicide and sexual abuse are often sensitive topics; therefore, advanced planning of how to handle such cases may alleviate resistance to implementation of EBPs to help maximally protect and treat individuals in need. Involving key stakeholders on the government level can also assist with the uptake of the protocol into national policy. Once in national policy, the prioritization of safety-related protection and activities is more likely to be realized.

Development of and Training on Safety Materials

When implementing mental health programs in LMIC, the lack of available mental health professionals results in a system of “task sharing,” in which individuals with little or no formal mental health training provide the direct mental health services in the community, hopefully supervised by individuals with greater mental health service capacity. For providers with little or no mental health experience, sometimes referred to as paraprofessionals, it can be stressful to interact with an individual who discloses suicidal ideation, violence, or abuse. Training materials developed for such paraprofessionals who will implement an EBP (assessment or treatment) should include (a) information on safety issues such as suicide, IPV, and abuse; (b) the role of service providers in prevention of and aid for safety-related issues, particularly the importance of asking directly about them; and (c) a complete step-by-step local safety protocol which includes supervision and wider community resources. Critical to training on safety matters is including behavioral rehearsal (Beidas, Cross, & Dorsey, 2013), or the continual practice of the new skill, because of the sensitivity of such topics. Training with role plays helps to reduce anxiety regarding the assessment and management of safety risk situations.

Information on suicide, IPV, and child abuse may include basic definitions, such as all the acts that may fall under child sexual abuse (e.g., touching, penetration) and for suicide defining those at highest risk (e.g., suicide ideation with intent, a plan, and access to lethal means). Prevalence estimates and information about local subpopulations at highest risk should be provided, if available. An interactive way to teach these topics is to organize an activity identifying myths and facts about each safety concern, having each paraprofessional review one with the larger group of community stakeholders as the group works to differentiate myths and facts.

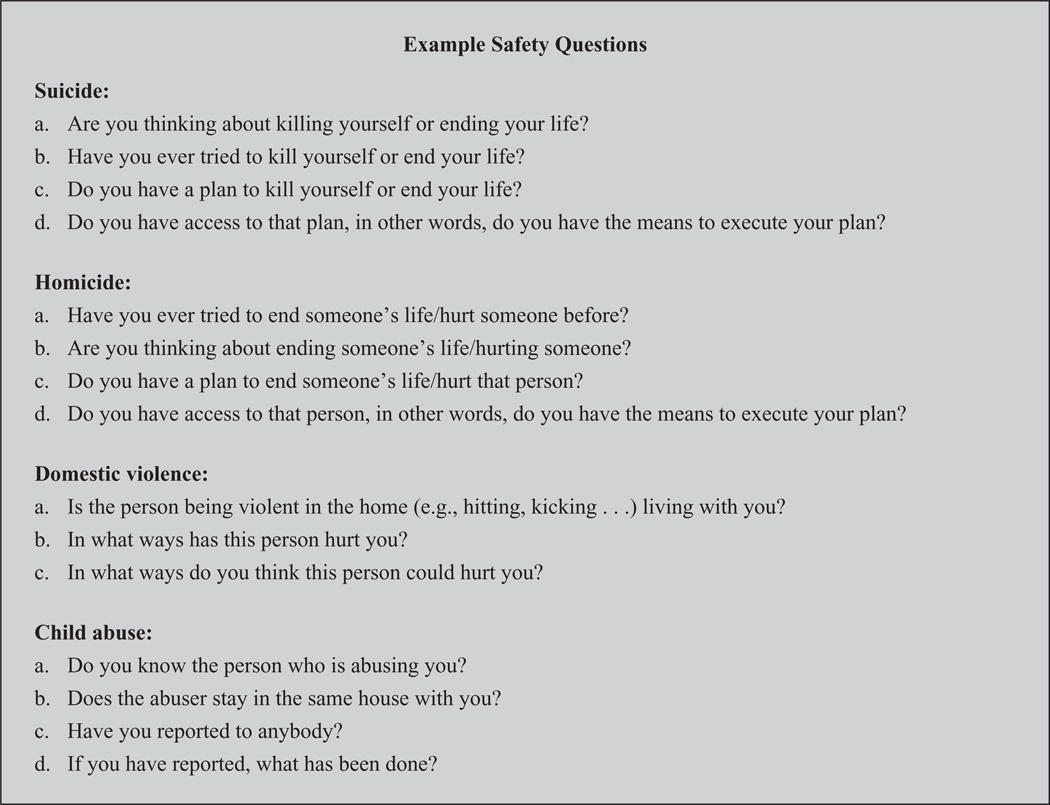

The role of a counselor or assessor (someone who may administer a mental health assessment tool within the community) is very important. Especially in LMIC where task sharing is used, counselors and assessors are often those embedded within the community and familiar to the population. This is a true asset to addressing safety issues because this familiarity affords a level of trust which can encourage reporting of safety-related issues. Counselors and assessors should understand that a good approach to identify and prevent safety risks is to ask directly about them (Quinnett, 1999). Asking directly about safety issues is often not comfortable and can be especially unnerving for someone with limited mental health background. Thus, training should include a detailed “step sheet” for asking key questions about these issues at the assessment and at every counseling or treatment session, with regular role-play practice of this skill (see Figure 2 for an example of specific questions). Counselors and assessors also practice how to explain that these questions are routinely asked to everyone to maximize safety.

Figure 2.

Sample safety questions.

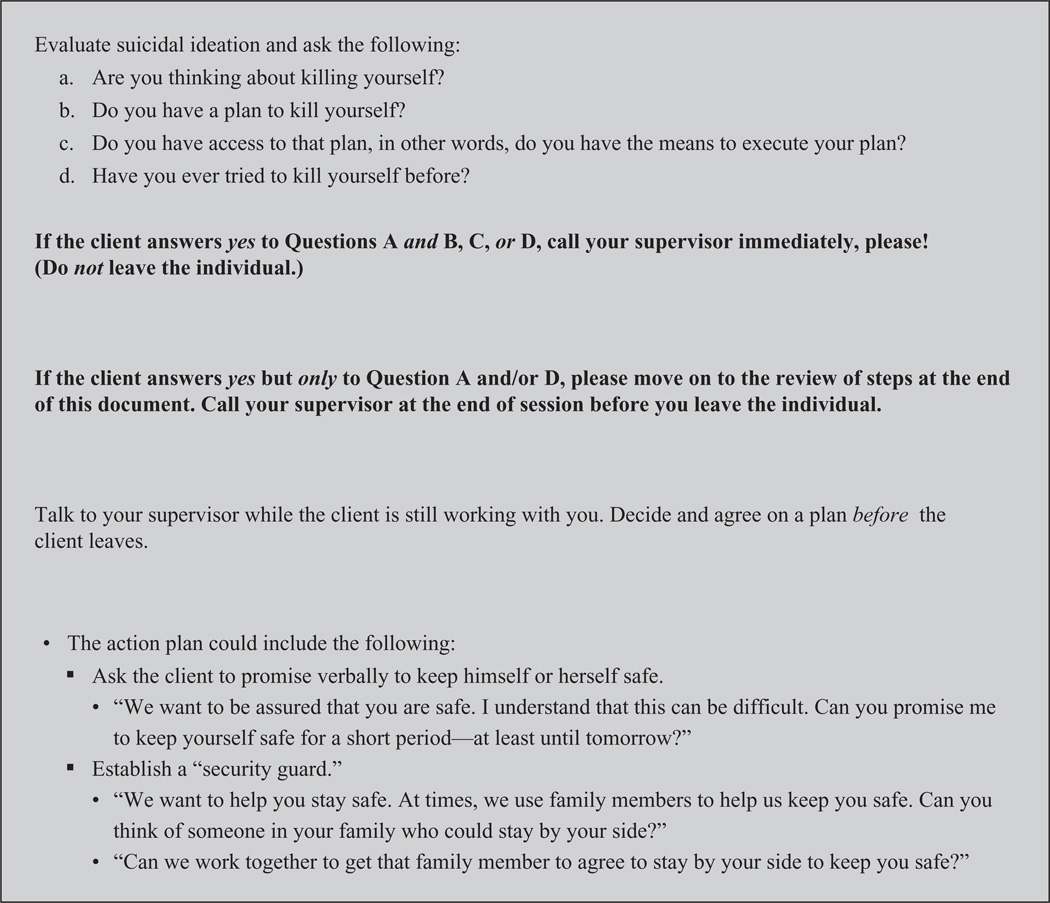

Developing a full safety protocol in LMIC is individualized to each site and program. Safety protocols vary depending on access to resources, location, and existing infrastructure. However, they should include several common elements: (a) how to assess risk, (b) how to identify warning signs, (c) how to help the client use their skills from the mental health or psychosocial program and/or their own resources, (d) how to implement immediate safety planning techniques (e.g., safety contract or safety watch), and (e) a clear order of contacts and documentation which needs to occur throughout the process. Figure 2 highlights the questions asked to assess risk. These questions are asked at every interaction with a client and reported to the supervisor. In addition to listing the questions, rules should be written and training conducted on what a counselor should do if risk is found based on “yes” or “no” responses to each item (see Figure 3 for an example).

Figure 3.

Sample guideline for suicide.

If only suicidal ideation is present, a counselor would move to identification of warning signs, help the client use their existing skills (if they have some), and/or implement immediate safety planning. This may include discussing situations that lead to such thoughts and/or working with the client using brief motivational skills such as cognitive restructuring to think in a different, more helpful way. In a case where an individual thinks of killing themselves, has a plan, and has the means to carry out this plan, a counselor would immediately call their supervisor and implement safety planning techniques, such as setting up a 24-hour watch (Stanley & Brown, 2012).

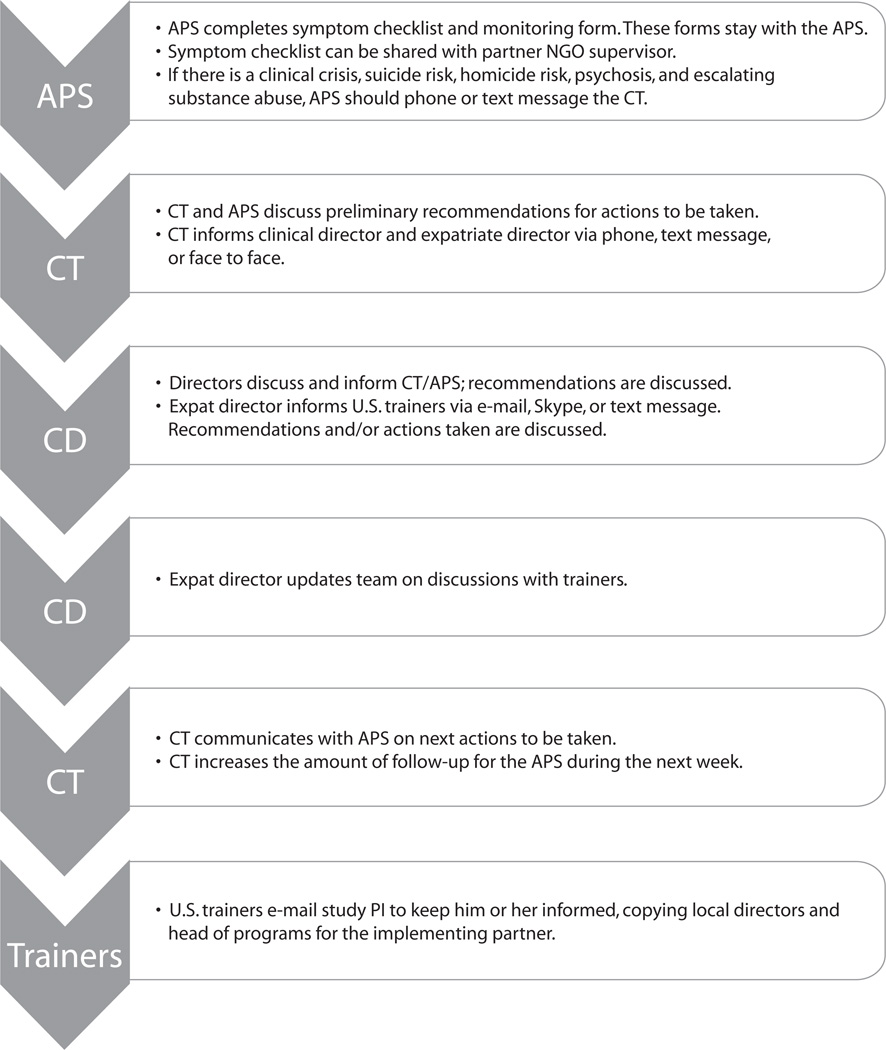

Finally, the implementing team follows a chain of contact for each type of case. Once a high- risk case is identified, a counselor is usually instructed to contact their clinical supervisor immediately. A phone consultation can help the paraprofessional (particularly those with limited mental health background) ask relevant questions to the client to determine level of risk for appropriate safety planning. The supervisor often also coaches the counselor through one of the safety planning techniques. The supervisor then communicates the occurrence of the safety issue and the steps taken to all the other relevant people within the service provider’s organization (see Figure 4 for an example flow chart from a RCT with local and international clinical partners involved). On a case-by-case basis, the counselor may be instructed by the supervisors to reach out to any one of the resources included on the list of community referral resources.

Figure 4.

Sample of communication flow for safety risk situations.

Note. This safety flow chart was developed in partnership between Johns Hopkins University and the International Rescue Committee for a trial of Cognitive Processing Therapy in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Bass et al., 2013). Additional information on this project can be obtained from the third author (JB). APS = counselor; NGO = nongovernmental organization; CT = supervisor; CD = project director; PI = principal investigator.

Ongoing Case Consultation

Each high-risk case needs to be handled in a personalized manner with consideration of the specific circumstances. Although certain procedures must be followed when working with high-risk cases (e.g., asking the safety questions, mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse), there is no prescribed formula a paraprofessional (assessor or counselor) can use for every client. When paraprofessionals have no or limited prior training in mental health, they may lack the ability to act on the spot in a flexible manner to adapt the safety protocol based on a client’s needs and situation. Thus, in addition to the initial call to the supervisor while sitting with a client who is considered a high-risk case, the counselor works closely with a team throughout the process of addressing a safety issue. These teams include the counselor and supervisors, along with others, such as local safety experts and leaders or stakeholders knowledgeable with local laws and systems. Each step is documented and sent through a line of communication including the consultation team to allow for feedback and ongoing adaptation of the plan.

Special Considerations

Paraprofessionals working with children need to be trained on specific techniques and steps for ensuring the safety of minors. For example, in most cases, an adult or guardian must be contacted and informed of the safety concerns. In addition to being a legal requirement in most countries, including most LMIC, it is also important to involve a guardian to assist in the safety planning and implementation when possible. Caregivers often generate valuable solutions to the safety issue, such as recommending a family member or friend who could watch a child and/or identifying triggers to the safety issue (e.g., child abuse) which help in creation of a safety plan. In some instances, a caregiver may be the perpetrator and contacting them may lead to increased safety risk for the child. In these instances, the consultation team, counselor, and supervisor would work together to find an alternate caregiver or another responsible adult.

Study Examples

Example 1: Psychometric Study on an Assessment for Adolescents—Zambia

Background

A study evaluating the psychometrics of an assessment tool for mental health, functioning, and HIV-risk behavior for orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) was recently completed in Zambia. The assessment was administered using the audio computer assisted self- interviewing (ACASI) system developed by Tufts University (n.d.; Tufts ACASI Systems), with assessors on-site to answer questions. Assessors in this study had varying levels of education, ranging from Grade 12 to undergraduate degrees, but all had little to no formal training in mental health. Assessors were hired based on (a) some understanding of research methodology, (b) possession of good supervisory and organizational skills, and (c) ability to speak and write in both English and one of the local study languages (Nyanja or Bemba).

A meeting with key local stakeholders and community leaders highlighted that there were no existing laws in Zambia which mandated providers to report clients with intent to harm or cases of abuse to the authorities or family members. In addition, no hospitals or residential settings existed that provided a high level of care for children or adolescents where, for example, they could be evaluated by a mental health professional and/or observed 24 hours a day if they are a danger to themselves. There were a few small shelters identified that could take children who had been abused. The local team agreed that none of the options identified were ideal for placement of an adolescent at risk of harming themselves, and the adolescent’s family and/or community were better situated to provide observation and appropriate care and support. The stakeholders generated a list of possible community resources outside of family/friends, including two police posts which handle child protection issues, five legal aid organizations, three community drop-in centers, five small community shelters/orphanages, one health clinic specifically for cases of child sexual abuse, three hospitals, seven HIV centers, seven hospices with pediatric centers, four social welfare organizations, four centers for people living with disabilities, and one 24-hour toll-free child hotline.

Stepwise safety procedures were developed and written in manual form, including questions and plans as shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3. For the study, 12 assessors and 2 supervisors were trained by the research team on the stepwise safety process and were provided the list of community resources. The research team put into place a collaborative team to deal with individual safety cases, which included two local supervisors who were previously trained in an EBT for trauma and experienced in implementing safety protocols from previous studies, one local psychologist based at the University of Zambia, one local psychiatrist based at the University Teaching Hospital, the mental health specialist for the Ministry of Health Zambia, two officers at the child protection unit of the local police, one expatriate licensed level clinical social worker, and one U.S.-based clinical psychologist.

Results

Over the course of 7 weeks, 204 adolescents were screened using the study assessment measure; 61 (30%) said yes to one or both questions on the measure pertaining to suicidal ideation. (Adolescents: “In the past 4 weeks, I have thought about killing myself.” “In the past 4 weeks, I have deliberately tried to hurt or kill myself.” Caregivers: “In the past month, the adolescent with me today has been talking about killing self.” “In the past month, the adolescent with me today has deliberately harmed themselves or has attempted suicide.”) The ACASI system flags when this happens with either a yellow or a red flag, and the assessor (who is always in the room) immediately asks the safety questions and/or refers them to a counselor on-site who asks these questions (see Figure 2). During the face-to-face interview with an assessor, 24 of the 61 adolescents stated that they did not understand the question on the measure and answered incorrectly. Thirty-seven of the 61 adolescents said yes to having thoughts of suicide, 13 of these 37 also said yes to having a plan, 8 had means to implement that plan, and 8 had previously attempted suicide. The methods the adolescents described they would use included (a) rat poison (n = 4), (b) over-dose using medication (n = 2), (c) using a knife (n = 1), and (d) using fire (n = 1). There were no cases of attempted or completed suicide in this study.

Regarding violence and abuse, 63 adolescents (30%) answered yes to ever experiencing being hit, kicked, or punched very hard at home (not including ordinary fights with brothers or sisters). Of those 63, 33 (52.4%) were female and 30 (47.6%) were male. There were 19 (9.1%; 12 female, 7 male) adolescents who reported that they had “an adult or someone much older touch their private sexual body parts or force sex on them.” There were 69 adolescents (32.9%) who reported either being hit/kicked/punched or experiencing sexual abuse; 13 (6.2%) reported both being hit/ kicked/punched and sexual abuse. Of the caregivers, 37 (13.1%) answered positive to the adolescent having been hit, kicked, or punched very hard at home. Nine guardians (4.4%) indicated that they knew the adolescent had been sexually abused in some way. Finally, in response to the question, “In the last 4 weeks until now, I took out my anger and frustrations on my adolescent by scolding, shouting at, or beating him or her,” 48 (23.3%) responded never true, 39 (18.9%) rarely true, 56 (27.2%) sometimes true, and 63 (30.6%) almost always true.

Case Example

A 15-year-old female, Margaret (pseudonym),1 indicated yes to the ACASI assessment question on suicidal ideation. An assessor asked Margaret the four safety questions and probed for additional information with the help of the supervisor. Margaret reported that she had current thoughts about killing herself ever since her mother died. Margaret reported being HIV-positive and explained that she would take an overdose of her antiretroviral medications (ARVs). She stated that she had tried to kill herself in the past yet still thinks about “it” when she is at home alone. The assessor normalized these suicidal thoughts and feelings and explained the importance of meeting with the client’s caregiver to keep her safe. When the assessor asked permission from Margaret to share this information with her caregiver (her father), Margaret became very upset and refused to allow the interviewer to disclose this information to her father.

The interviewer was uncertain of how to handle the situation and contacted the supervisor again as instructed in the safety protocol. The supervisor joined the session in person and worked with the interviewer to probe and find out more about why Margaret did not want to share this information with her father. Margaret shared that she was afraid that this information would upset her father and as a result, she might be beaten. The supervisor identified that Margaret had now raised a second safety issue (abuse) and asked her the safety questions around child abuse to assess the level of physical abuse in the home. Margaret stated that the father did not beat her hard, but, as is common in Zambia, the father used spankings to discipline her. After explaining she was going to get additional information, the supervisor briefly excused herself from the room and contacted the case consultation team to discuss next steps.

During the case consultation with the project director, it was decided that the supervisor needed to take several actions. First, a child protection unit was contacted and notified of the situation. The responding officer determined that the case was of minimal risk but that they would follow up as needed with the family. Second, the case was discussed with the local expert on safety issues (found from the list of community resources) to obtain his recommendations. Consensus was reached among the consultation team that the supervisor would help the assessor set up an individual safety plan for Margaret. It was suggested that the supervisor ask Margaret if there was another person who also cares for her, such as an aunt or grandmother or neighbor. Ideally, the team suggested that both the father and another caregiver should be included in the plan. The project director helped coach the supervisor on how to talk with Margaret and her father through role-plays to assure development of a detailed safety plan as well as having discussion with the father about effective parenting techniques and the impact of corporal punishment.

The supervisor learned from Margaret that a neighbor sometimes cared for her and her siblings when the father was working and gave permission to discuss safety with both the father and the neighbor. The safety plan included (a) Margaret giving her safety “word” or promise that she would not try to kill herself in the next day, (b) the father and neighbor agreeing to take turns watching Margaret closely over the next 24 hours to assure her safety, (c) the father agreeing to hide Margaret’s ARVs and being responsible for administering her appropriate doses daily, and (d) the supervisor making an appointment to meet Margaret at the house the following day. During the follow-up visit, the supervisor reassessed Margaret’s current state by asking the four safety questions. Margaret was still thinking about killing herself but said she would not do it and did not have a plan. The supervisor reconfirmed Margaret’s safety promise and the safety watch (now increased to 48 hours). The supervisor also spent 20 min with the father asking about disciplinary actions he used and the effects these have on the child. The father admitted to sometimes spanking Margaret but was agreeable to limiting that, stating that he did not want to abuse his daughter. The family was also referred to a local psychosocial counseling center.

Example 2: Baseline Assessment of Randomized Controlled Trial for Mental Health Services for Female Survivors of Sexual Violence: Democratic Republic of Congo

Background

A randomized controlled trial of CPT for survivors of sexual violence (specifically rape) was conducted in rural villages in South Kivu province in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC; Bass et al., 2013). To identify those in need of this mental health service, a validated assessment tool was used to assess female survivors for mental health symptoms, which included two questions related to suicidal ideation: (a) “In the last 2 weeks, how frequently have you had thoughts of ending your life?” and (b) “In the last 2 weeks how frequently have you had thoughts about hurting yourself?” At the baseline assessment to determine study eligibility, all women who reported any level of suicidal ideation (i.e., responded to either of these questions with any level of affirmation) were asked the safety questions (Figure 2).

Local community and stakeholders’ meetings identified two organizations located in the main town of Bukavu providing services for adults in high-risk situations. However, the village sites where clients were located and where the study was being conducted were rural and were far away from Bukavu on poor roads. It was decided by the community that cases would need to be handled by the psychosocial assistant who was already located in the village and was a staff member of the local partner NGOs providing psychosocial and mental health care for survivors in each village, with help from community members and families. Very severe cases could be referred to the main hospital in Bukavu which provided services for sexual violence survivors, but transportation and logistics would be burdensome so this was not seen as a strong solution. Assessors, the psychosocial assistants, and clinical supervisors were trained in the locally developed safety protocol and chain of communication (see Figure 4). The case consultation team consisted of two expatriate licensed social workers based at the headquarters in Bukavu, one local clinical director, two program directors for International Rescue Committee, two U.S.-based intervention trainers, one U.S.-based clinical psychologist, and the study principal investigator.

Results

Baseline assessments for the study occurred in 15 different villages resulting in 494 women assessed. There were 47 women (10%) who reported experiencing at least one of the two suicidal ideation questions in the previous 2 weeks. Of these 47, 33 had plans, 25 had access to means, and 25 reported a history of attempts. The most methods women stated using included drowning (plan n = 10, past attempt n = 8), hanging (plan n = 8, past attempt n = 8), rat poison (plan n = 5, past attempt n = 2), battery acid (plan n = 5, past attempt n = 1), knife (plan n = 2, past attempt n = 2), overdose (malaria medication; plan n = 2, past attempt n = 1), other form of poison (plan n = 1, past attempt n = 1), jump in front of a car (plan n = 2, past attempt n = 0), jump from hill/cliff (plan n = 0, past attempt n = 1), and starvation (plan n = 0, past attempt n = 1).

Case Example

During the baseline assessments for eligibility, a 38-year-old woman named Cecilia (pseudonym) reported that she had thoughts of wanting to kill herself. The interviewer immediately contacted the supervisor, who was on-site as part of the study team, who then worked with the client to assess the level of suicide risk by asking the four safety questions. Cecilia reported that she had current thoughts of wanting to kill herself, had a plan to drown in the river by her house, and had tried to kill herself in the past by drowning but did not succeed because she was not weighted down properly.

As per the safety protocol, the supervisor on-site was to call the clinical supervisor at headquarters to discuss and develop an action plan. Unfortunately, lines were down and the radio was not going through to the NGO base, so the supervisor could not report the case to the consultation team. This was an issue that the study team had anticipated, and therefore, extra time was spent training the supervisors to be able to handle these cases as needed without assistance. The supervisor asked additional questions about triggers to her suicidal ideation (e.g., what times or situations make her feel more like killing herself), learning that Cecilia had these thoughts when she did not have money for food and when her children were hungry. The supervisor set up a safety contract wherein Cecilia promised not to hurt or kill herself in the next 24 hours. The supervisor also felt Cecilia needed someone watching her, and Cecilia was willing to include her father in her safety plan. The supervisor physically went with Cecilia to the family’s home and met with Cecilia and her father together. They were able to agree on a plan for safety watch where the father would be in the presence of the daughter for the next 24 hours. When the daughter was changing or using the bathroom, it was agreed that Cecilia’s sister would be present. The safety watch was reviewed with the family and then role-played so the family truly understood how closely they needed to watch Cecilia.

The supervisor went to their house and followed up with Cecilia and her father the next day to reassess suicidal ideation and extend the safety contract. The supervisor was able to send a text message via mobile phone to the NGO base to inform the case consultation team and update them on the case. After two follow-up visits with Cecilia, her risk had dropped with infrequent ideation and no plan. The family was also much more aware of Cecilia’s mood and continued to observe her more often. It was determined that the psychosocial assistant located in that village could take over monitoring of the case and would continue to inform the supervisor and consultation team. The supervisor returned to the NGO base to fully inform the case consultation team and report any feedback back to the psychosocial assistant.

Example 3: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Zambia With Children, Adolescents, and Families

A safety protocol continues beyond an initial assessment or baseline measurement into the study or service project. A study evaluating the effectiveness of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT; Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2006) for orphans and vulnerable children (inclusive of adolescents and caregivers) aged 6–18 years was recently completed in Zambia (Skavenski, Murray et al., 2014). Inclusion was based on a score of 38 or higher on the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index, which was locally validated (Murray et al., 2011a). Children and caregivers were assigned to a local counselor trained in TF-CBT via the apprenticeship model, which includes intensive ongoing supervision (Murray et al., 2011b).

Results

Eighteen high risk cases were identified. Although receiving treatment, 8 children reported suicidal ideation and a plan to carry this out. The plans were to cut wrist with a razor (n = 2), drink battery acid (n = 2), hang themselves (n = 1), throw themselves in a dam (n = 1), use a knife (n = 1), and throw themselves in front of a moving vehicle (n = 1). Of these 8, all but 1 had the means to carry out the plan, and 3 had previously tried to kill themselves. There were 5 children who indicated that they were being sexually abused. As an example of a success, in one case, the child moved in with an aunt temporarily while the family asked the abuser (a family member) to move out of the house. The abuser is no longer living in the home.

Unfortunately, however, there are also some cases which are not as successful. One incident was reported where a stepfather was the abuser, and in the end, the family relocated, and officials are still trying to track them down. Two children have reported homicidal ideation, one child reported wanting to kill another child, and one child was planning to strangle his brother. Three children reported physical abuse. In one case, it was a caretaker at a center, who was eventually terminated from their position. In another case, after investigation, the child was removed from the home and placed in a relative’s care. In the third case, the counselor was able to contract with the family, follow up on site regularly, and work on positive parenting to eliminate the abuse.

Challenges

Challenges are to be expected when implementing safety protocols in LMIC which lack resources and mental health services. Logistical challenges include issues with transportation, space to conduct safety assessments and planning, phone access and connection, and/or coordination of services. For example, in DRC, ongoing violence prevented the teams from using roads on certain days, and phone networks were often poor, resulting in limited contact between those handling high risk–cases directly and their supervisor and case consultation team. Although not ideal, those working in rural areas received additional training to deal with these logistic issues and, over the course of the study, showed ability to handle all the cases listed earlier with no suicidal attempts.

Another challenge is staffing for the safety protocol, resource list, and consultation team and thinking through scope of work changes and/or compensation. Handling of high-risk cases can be intense and time consuming. Actions need to be taken immediately even if the timing is not “ideal” (e.g., someone is expected back in the office or would like to leave for the day). Support from management is also critical to encourage and understand the time commitment to such cases. Many of these challenges can be addressed if groups discuss them before any roll out of the safety protocol occurs. For example, the group may brainstorm possible problems and directly ask those involved in the safety protocol, wider resource list, or consultation team what their concerns are.

Discussion

Although high-risk cases exist in any setting, working on the mental health issues of populations exposed to and at risk for violence are likely to illicit concerns about safety. It is widely known that safety issues such as suicide, IPV, and abuse are largely underreported and/or ignored. Barriers to understanding or treating safety issues often arise from two circumstances. First, personnel (e.g., staff, lay counselors, assessors in a study, community volunteers) are not trained on how to address safety. When personnel are not trained to ask, it frequently results in them not taking the initiative to do so on their own, and therefore, safety issues go unnoticed and/or unreported. Secondly, there is a lack of capacity to handle high-risk cases on both an individual and macrolevel. In most LMIC, there are limited personnel trained in treatments for clients with higher level risks such as suicidal thought and intent. This results in a fear of asking about safety because they do not know how to help or do not have the capacity to help. On a government and/or organizational level, if policies are introduced requiring providers to ask clients about safety issues, the system may face a need that far exceeds the capacity. In addition, laws and resources that do exist are often hard to find, disjointed, and/or not well coordinated. In the case of child abuse, there may be no laws on mandated reporting, as well as understaffed or underresourced abuse-focused systems. The lack of skill and resources with which to address safety issues such as suicide, IPV, and/or abuse could prevent organizations from not only refraining from asking direct questions about safety, but even avoiding working with such populations.

Safety issues as a possible barrier to implementing EBP (assessment and/or treatment) in LMIC is one that we feel can begin to be addressed with relevant implementation strategies (Powell et al., 2012). The implementation of safety protocols, as described earlier, has been demonstrated to be feasible in LMIC when a stepwise process is followed. With training, the community can be equipped to handle most high-risk cases without higher level infrastructures, such as psychiatric inpatient hospitals or highly trained personnel (e.g., psychiatrists). In settings where the authors have implemented such safety protocols, there were no suicides, and all safety concerns were addressed by a counselor or staff trained in the protocol and the community.

Future Directions

In settings where access to mental health treatments is limited, having training in brief crisis interventions such as safety plans may be especially useful (Stanley & Brown, 2012). The anecdotal results from the studies presented suggest that safety protocols are needed, feasible, and accepted in LMIC. As global mental health continues to grow as a priority in LMIC and EBPs are recommended, it will become increasingly important that all mental health service providers include an integrated and comprehensive safety planning component. Safety protocols that are integrated as standard of care within all health systems could help prevent and mitigate the consequences of suicide, IPV, and child abuse. Personnel working with at-risk populations should be required to have basic training in how to ask about high-risk situations and how to address those situations using a safety protocol. Implementation research clearly shows that support by governments and organizations is critical (e.g., Aarons, Wells, Zagursky, Fettes, & Palinkus, 2009). In LMIC, support in the form of official policies, as well as changes to job descriptions, such that providers are mandated to identify and address safety issues among clients, will be essential to facilitate the use of safety plans.

Footnotes

All case studies have been altered and pseudonyms are used to protect confidentiality.

Contributor Information

Laura K. Murray, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

Stephanie Skavenski, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

Judith Bass, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

Holly Wilcox, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

Paul Bolton, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

Mwiya Imasiku, University of Zambia, School of Medicine, Lusaka, Zambia.

John Mayeya, Zambia Ministry of Health, Lusaka, Zambia.

References

- Aarons GA, Wells RS, Zagursky K, Fettes DL, Palinkas LA. Implementing evidence-based practice in community mental health agencies: A multiple stakeholder analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(11):2087–2095. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass JK, Annan J, McIvor MS, Kaysen D, Griffiths S, Cetinoglu T, Bolton PA. Controlled trial of psychotherapy for Congolese survivors of sexual violence. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(23):2182–2191. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass JK, Ryder RW, Lammers MC, Mukaba TN, Bolton PA. Post-partum depression in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: Validation of a concept using a mixed-methods cross-cultural approach. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2008;13(12):1534–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT, Fergusson DM, Deavoll BJ, Nightingale SK. Prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders in persons making serious suicide attempts: A case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153(8):1009–1014. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Cross W, Dorsey S. Show me, don’t tell me: Behavioral rehearsal as a training analogue fidelity tool. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;21(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT. National intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/NISVS_Report2010-a.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Bass J, Betancourt T, Speelman L, Onyango G, Clougherty KF, Verdeli H. Interventions for depression symptoms among adolescent survivors of war and displacement in northern Uganda: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(5):519–527. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Bass J, Neugebauer R, Clougherty K, Verdeli H, Ndogoni L, Weissman M. Results of a clinical trial of a group intervention for depression in rural Uganda. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;279(3):117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Lee C, Haroz EE, Murray LK, Dorsey S, Robinson C, Bass J. Randomized controlled trial of a community-based mental health treatment for comorbid disorders among Burmese refugees in Thailand. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001757. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JT, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(3):395–405. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Child maltreatment: Prevention strategies. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/childmaltreatment/prevention.html.

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Neglect. 1994a;18(5):409–417. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. Current information on the scope and nature of child sexual abuse. Future Child. 1994b;4(2):31–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Lannen P, Quayle E. Optimus study: A cross-national research initiative on protecting children and youth. Synthesis. Zurich, Switzerland: UBS Optimus Study; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Kemp A, Thoburn J, Sidebotham P, Radford L, Glaser D, MacMillan H. Child maltreatment: Recognising and responding to child maltreatment. Lancet. 2009;373(9658):167–180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14(2):99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women (Population Reports, Series L, No. 11) Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Population Information Program; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Ribeiro JD. Assessment and management of suicidal behavior in children and adolescents. Pediatric Annals. 2011;40(6):319–324. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20110512-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordans MJ, Komproe IH, Tol WA, De Jong JT. Screening for psychosocial distress amongst war-affected children: Cross-cultural construct validity of the CPDS. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(4):514–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MM. Suicide prevention and developing countries. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2005;98(10):459–463. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.10.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Jordans MJ, Tol WA, Luitel NP, Maharjan SM, Upadhaya N. Validation of cross-cultural child mental health and psychosocial research instruments: Adapting the Depression Self-Rating Scale and Child PTSD Symptom Scale in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):127. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, Zwi A, Lozano R. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Institution; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lalor K. Child sexual abuse in sub-Saharan Africa: A literature review. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(4):439–460. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley GL, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The improvement guide: A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau EJ, Holmes M, Chasedunn-Roark J. Gynecologic health consequences to victims of interpersonal violence. Women’s Health Issues. 1999;9(2):115–120. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(98)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer VA. U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;158:478–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-6-201303190-00588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Bass J, Chomba E, Haworth A, Imasiku M, Thea D, Bolton P. Validation of the child post-traumatic stress disorder-reaction index in Zambia. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2011a;5(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Bolton PA, Jordans M, Rahman A, Bass J, Verdeli H. Building capacity in mental health interventions in low resource countries: An apprenticeship model for training local providers. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2011b;5(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Haroz E, Lee C, Alsiary MM, Haydary A, Bolton P. A common elements treatment approach for adult mental health problems in low- and middle-income countries. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 1. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V. The future of psychiatry in low- and middle-income countries. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39(11):1759–1762. doi: 10.1017/s0033291709005224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, Kirkwood BR. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counselors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): A cluster randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9758):2086–2095. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, McMillen C, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger A, York JL. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Medical Care Research and Review. 2012;69(2):123–157. doi: 10.1177/1077558711430690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2009;36(1):24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinnett P. QPR: Ask a question, save a life. The QPR Institute and suicide awareness/voices of education. 1999 Retrieved from http://www.qprinstitute.com/

- Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behavior therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902–909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reza A, Breiding MJ, Gulaid J, Mercy JA, Blanton C, Mthethwa Z, Anderson M. Sexual violence and its health consequences for female children in Swaziland: A cluster survey study. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1966–1972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudan I, El Arifeen S, Black RE, Campbell H. Childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea: Setting our priorities right. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2007;7(1):56–61. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70687-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):878–889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Craft L. Methods of adolescent suicide prevention. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl. 2):113–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):232–246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012;19(2):256–264. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Alink LRA. Cultural-geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. International Journal of Psychology. 2013;48(2):81–94. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.697165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakersman-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16(2):79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufts University. ACASI system. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://acasi.tufts.edu/

- Whetten K, Ostermann J, Whetten RA, O’Donnell K, Thielman N. More than the loss of a parent: A 5 country study of potentially traumatic experiences of orphaned and abandoned children aged 6–12. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24(2):174–182. doi: 10.1002/jts.20625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja S, Dutton M. Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(8):785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2002. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/full_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. GBV interventions guidelines. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/pht/GBVGuidelines08.28.05.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Mental health GAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: Mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Child maltreatment. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence injuryprevention/violence/child/en/index.html.

- World Health Organization. Suicide prevention (SUPRE) 2014 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/