Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate whether labor is associated with lower odds of respiratory morbidity among neonates born from 36 to 40 weeks of gestation and to assess whether this association varies by gestational age and maternal diabetic status.

METHODS:

We conducted a secondary analysis of women in the Assessment of Perinatal Excellence obstetric cohort who delivered across 25 U.S. hospitals over a 3-year period. Women with a singleton liveborn non-anomalous neonate who delivered from 36 to 40 weeks of gestation were included in our analysis. Those who received antenatal corticosteroids, underwent amniocentesis for fetal lung maturity, or did not meet dating criteria were excluded. Our primary outcome was composite neonatal respiratory morbidity, which included respiratory distress syndrome, ventilator support, continuous positive airway pressure, or neonatal death. Maternal characteristics and neonatal outcomes between women who labored and those who did not were compared. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between labor and the primary outcome. Interactions between labor and diabetes mellitus and labor and gestational age were tested.

RESULTS:

Our analysis included 63,187 women who underwent labor and 10,629 who did not. There was no interaction between labor and diabetes mellitus (P=.90). However, there was a significant interaction between labor and gestational age (P=.01). In the adjusted model, labor was associated with lower odds of neonatal respiratory morbidity compared with no labor for neonates delivered from 36–39 weeks of gestation. A 1-week increase in gestational age was associated with a 1.2 times increase in the adjusted odds ratio for the neonatal outcome comparing labor and no labor.

CONCLUSION:

Labor was associated with lower odds of the composite outcome among neonates delivered from 36–39 weeks of gestation. The magnitude of this association varied by gestational age. The association was similar for women with or without diabetes mellitus.

Respiratory complications are a common indication for admission to the neonatal intensive care unit among both preterm and term neonates.1–3 The risk of neonatal respiratory morbidity is dependent on a number of maternal and neonatal clinical factors. Gestational age is an independent predictor of neonatal respiratory morbidity even in late preterm (34–36 weeks) and early term (37–38 weeks) gestation.1,4–7 Maternal diabetic status also contributes to the risk of neonatal respiratory morbidity. Neonates born to women with diabetes mellitus, either pregestational or gestational, are at heightened risk for respiratory morbidity.3,8,9 In addition, cesarean delivery performed in the absence of labor is associated with an increased risk of neonatal respiratory morbidity.6,10–17 Although cesarean delivery without labor has been compared with vaginal delivery or emergent cesarean delivery (cesarean delivery performed after the onset of labor), whether labor is an independent factor associated with neonatal respiratory morbidity remains uncertain. Similarly, whether and to what extent there is a relationship between labor and two key risk factors for neonatal respiratory morbidity—gestational age and diabetes mellitus—remains poorly understood.

We hypothesize that, even after adjusting for relevant covariates, labor is associated with lower odds of neonatal respiratory morbidity and that the magnitude of this association varies by gestational age. We also hypothesize that for neonates of women with diabetes mellitus, labor is associated with additional respiratory benefit. Thus, our primary objective was to evaluate whether labor, rather than route of delivery, is associated with lower odds of respiratory morbidity among neonates of women who deliver from 36–40 weeks of gestation. Our secondary objective was to determine whether the association of respiratory morbidity with labor varies by gestational age or maternal diabetes mellitus.

METHODS

This study is a secondary analysis of the Assessment of Perinatal Excellence study, which was an observational cohort of 115,502 mother and neonatal pairs who delivered at one of the 25 hospitals in the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Deliveries occurred between March 2008 and February 2011. All participating sites obtained approval from their respective institutional review boards. A detailed description of the study design and methods has been published previously.18 Briefly, inclusion criteria for the parent study included women who delivered on randomly selected days if they were admitted with a living fetus at 23 weeks of gestation or beyond. Trained and certified study personnel abstracted data from the medical records of the participants that included patient demographic and maternal and neonatal clinical characteristics.

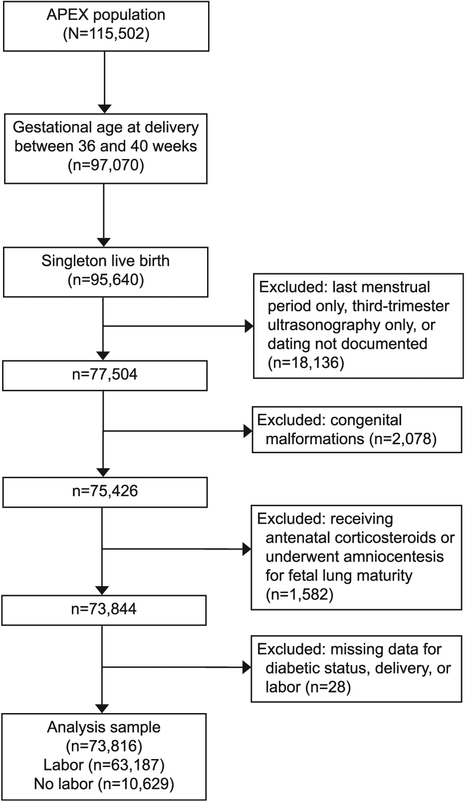

Women who delivered from 36–40 weeks of gestation with a singleton liveborn neonate without major congenital anomalies were included in our secondary analysis. Those who received antenatal corticosteroids, underwent amniocentesis for fetal lung maturity, or had insufficient dating information (method of dating was not specified or dated only by last menstrual period or third-trimester ultrasound scan) were excluded (Fig. 1). Labor was defined in the original Assessment of Perinatal Excellence study data set as painful regular uterine contractions that occurred spontaneously or as a result of medical intervention (labor induction or augmentation). Our primary outcome was composite neonatal respiratory morbidity, which included respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), ventilator support, or neonatal death. Respiratory distress syndrome was diagnosed if the following three criteria were met: 1) the clinical diagnosis of RDS was documented in the chart, 2) oxygen therapy was initiated within the first 24 hours of life at a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.4 or greater, and 3) the duration of oxygen support was 24 hours or more. Continuous positive airway pressure was defined as the use of CPAP outside of the delivery room, started within the first 24 hours of life. Ventilator support was defined as mechanical ventilation that was initiated during the first 24 hours of life. For neonates who required ventilator support, the duration of ventilator support was defined as the total number of days or partial days for which ventilator support was required. These variables were selected as clinically important respiratory morbidities that would require neonatal intensive care.

Fig. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion of patients. APEX, Assessment of Perinatal Excellence.

Univariable analyses were performed using χ2, Fisher exact, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate, to compare maternal characteristics and neonatal outcomes between women who labored and those who did not. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between labor and the primary outcome and adjusted for diabetes mellitus, maternal age, race and ethnicity, hypertensive disorders, neonatal sex, gestational age at delivery, and study site. Gestational age was evaluated as a continuous variable. Interactions between labor and gestational age, and labor and diabetes mellitus were tested. Statistical significance was defined as P<.05 and all tests were two-tailed. No imputation for missing data was performed. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.4).

RESULTS

Our analysis included a total of 73,816 women. The majority were dated by last menstrual period consistent with a subsequent ultrasound scan (74%); other methods of dating were by first-trimester ultrasound scan only (15%), second-trimester ultrasound scan only (9%), or assisted reproductive technology (2%). Participants included in this analysis represented a racially and ethnically diverse group of women (Table 1). As anticipated, a minority of women had pregestational diabetes mellitus (1%) or gestational diabetes mellitus (6%). Among those included in our analysis, 63,187 (86%) underwent labor and 10,629 women (14%) did not. Among women who labored, 10,561 (16.7%) underwent cesarean delivery. The indications for these cesarean deliveries were labor dystocia (36%); nonreassuring fetal status (27%); prior cesarean delivery (18%); failed induction (7%); mal-presentation (7%); maternal medical condition (1%); placenta or cord abnormality (1%); or other reasons (3%). For women who did not labor, the indications for cesarean delivery were prior uterine surgery (cesarean delivery or myomectomy, 74%); malpresentation (12%); elective (5%); maternal medical condition (2%); nonreassuring fetal status (2%); placenta or cord abnormality (2%); or other reasons (3%).

Table 1.

Maternal Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Labor Status

| Characteristic | Labor (n=63,187) | No Labor (n=10,629) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (y) | 27.7±6.1 | 30.6±5.7 | <.001 |

| Race-ethnicity | <.001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 27,688 (43.8) | 5,075 (47.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 12,622 (20.0) | 1,825 (17.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 3,249 (5.1) | 500 (4.7) | |

| Hispanic or Latina | 16,579 (26.2) | 2,771 (26.1) | |

| Other or unknown | 3,049 (4.8) | 458 (4.3) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.9±6.1 | 33.4±7.2 | <.001 |

| Cigarette use during pregnancy | 5,736 (9.1) | 1,058 (10.0) | .004 |

| Nulliparous | 26,549 (42.0) | 1,632 (15.4) | <.001 |

| Hypertensive disorder | 6,715 (10.6) | 1,126 (10.6) | .92 |

| Diabetes mellitus | <.001 | ||

| Pregestational | 666 (1.1) | 269 (2.5) | |

| Gestational | 3,655 (5.8) | 1,020 (9.6) | |

| Gestational age at delivery (wk) | 39.2±1.1 | 38.9±0.9 | <.001 |

| Cesarean delivery | 10,561 (16.7) | 10,629 (100) | <.001 |

BMI, body mass index.

Data are mean±SD or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Number of missing values: BMI, n=1,432; cigarette use during pregnancy, n=59; parity, n=9.

Bold indicates statistically significant findings.

Maternal demographic and clinical characteristics by labor status are displayed in Table 1. Women who labored delivered at a gestational age (mean±SD 39.2±61.1 week) that was higher, although small in absolute magnitude, as compared with those who did not labor (mean±SD 38.9±60.9 weeks of gestation, P<.001). Neonatal outcomes by labor status are displayed in Table 2. Neonates of women who labored were more likely to have lower birth weights compared with neonates of women who did not labor (mean±SD 3,329±457 vs 3,427±515 g, P<.001). Additional descriptive data are available in Tables 3–5.

Table 2.

Neonatal Outcomes by Labor Status

| Outcome | Labor (n=63,187) | No Labor (n=10,629) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight (g) | 3,329±457 | 3,427±515 | <.001 |

| Male sex | 32,254 (51.0) | 5,337 (50.2) | .11 |

| Composite respiratory outcome | 1,428 (2.3) | 347 (3.3) | <.001 |

| RDS | 678 (1.1) | 161 (1.5) | <.001 |

| CPAP | 933 (1.5) | 233 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Ventilator support | 287 (0.5) | 61 (0.6) | .10 |

| Neonatal death | 10 (0.02) | 2 (0.02) | .69 |

| Duration of ventilator support (d)* | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | .05 |

RDS, respiratory distress syndrome; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure.

Data are mean±SD, n (%), or median (quartile 1–quartile 3) unless otherwise specified.

Number of missing values: birth weight, n=4; days on ventilator, n=2.

Bold indicates statistically significant findings.

Duration of ventilator support is among those with ventilator support.

Table 3.

Frequency Table of Indication for Cesarean Delivery by Gestational Age and Labor Status

| Gestational Age (wk) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication for Cesarean Delivery | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | |||||

| Labor (n=580) | No Labor (n=431) | Labor (n=1,189) | No Labor (n=909) | Labor (n=2,319) | No Labor (n = 1,941) | Labor (n=3,274) | No Labor (n=6,577) | Labor (n=3,199) | No Labor (n = 771) | |

| Elective | 6 (1.0) | 15 (3.5) | 24 (2.0) | 41 (4.5) | 41 (1.8) | 91 (4.7) | 36 (1.1) | 346 (5.3) | 24 (0.8) | 57 (7.4) |

| Prior cesarean delivery | 192 (33.1) | 211 (49.0) | 406 (34.1) | 518 (57.0) | 788 (34.0) | 1,424 (73.4) | 436 (13.3) | 5,174 (78.7) | 111 (3.5) | 427 (55.4) |

| Myomectomy | 0 (0) | 7 (1.6) | 3 (0.3) | 37 (4.1) | 5 (0.2) | 23 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 30 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Presumed macrosomia | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) | 5 (0.4) | 15 (1.7) | 26 (1.1) | 50 (2.6) | 38 (1.2) | 195 (3.0) | 41 (1.3) | 84 (10.9) |

| Placenta or cord indication | 10 (1.7) | 51 (11.8) | 21 (1.8) | 55 (6.1) | 24 (1.0) | 35 (1.8) | 52 (1.6) | 23 (0.4) | 34 (1.1) | 4 (0.5) |

| Nonreassuring fetal status | 132 (22.8) | 47 (10.9) | 245 (20.6) | 59 (6.5) | 468 (20.2) | 44 (2.3) | 920 (28.1) | 40 (0.6) | 1,048 (32.8) | 31 (4.0) |

| Dystocia | 99 (17.1) | 0 (0) | 256 (21.5) | 0 (0) | 608 (26.2) | 3 (0.2) | 1,291 (39.4) | 6 (0.1) | 1,539 (48.1) | 3 (0.4) |

| Malpresentation | 73 (12.6) | 62 (14.4) | 111 (9.3) | 129 (14.2) | 192 (8.3) | 211 (10.9) | 202 (6.2) | 677 (10.3) | 113 (3.5) | 148 (19.2) |

| Maternal medical condition | 21 (3.6) | 34 (7.9) | 20 (1.7) | 54 (5.9) | 37 (1.6) | 58 (3.0) | 39 (1.2) | 85 (1.3) | 26 (0.8) | 17 (2.2) |

| Failed induction | 47 (8.1) | 0 (0) | 98 (8.2) | 1 (0.1) | 125 (5.4) | 0 (0) | 250 (7.6) | 0 (0) | 255 (8.0) | 0 (0) |

Data are n (%).

Missing data: 36 weeks, n=2; 38 weeks, n=7; 39 weeks, n=11; 40 weeks, n=6.

Table 5.

Frequency of Primary Outcome by Gestational Age and Diabetic Status

| Gestational Age (wk) | Labor | No Labor |

|---|---|---|

| 36 (n=2,890) | ||

| Overall | 193 (7.8) | 46 (10.7) |

| No diabetes | 169 (7.8) | 35 (10.1) |

| Diabetes | 24 (8.4) | 11 (13.1) |

| 37 (n=7,162) | ||

| Overall | 222 (3.6) | 60 (6.6) |

| No diabetes | 184 (3.3) | 43 (5.8) |

| Diabetes | 38 (5.6) | 17 (10.2) |

| 38 (n=15,225) | ||

| Overall | 247 (1.9) | 58 (3.0) |

| No diabetes | 217 (1.8) | 43 (2.7) |

| Diabetes | 30 (2.7) | 15 (4.6) |

| 39 (n=29,605) | ||

| Overall | 403 (1.8) | 162 (2.5) |

| No diabetes | 370 (1.7) | 146 (2.5) |

| Diabetes | 33 (2.0) | 16 (2.4) |

| 40 (n = 18,934) | ||

| Overall | 363 (2.0) | 21 (2.7) |

| No diabetes | 350 (2.0) | 18 (2.5) |

| Diabetes | 13 (2.2) | 3 (5.7) |

Data are n (%).

The primary outcome was defined as composite neonatal respiratory morbidity, which included respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), ventilator support, or neonatal death.

In unadjusted analyses, neonates of women who labored were less likely to experience the primary composite respiratory outcome as compared with neonates of women who did not labor (2.3% vs3.3%, P<.001). Individual outcomes of RDS (1.1% vs 1.5%, P<.001) and CPAP (1.5% vs 2.2%, P<.001) occurred less frequently in women who had labor compared with women who did not. Neonates of women who labored and who did not labor were similar with regard to the need for ventilator support (0.5% vs 0.6%, P=.10) and the duration of ventilator support for those neonates who required mechanical ventilation (median: 1 day vs 2 days, P=.05). Table 6 displays the frequency of the primary outcome by labor status and gestational age.

Table 6.

Neonatal Composite Respiratory Morbidity Outcome by Labor Status and Gestational Age

| Gestational Age at Delivery (wk) | Labor | No Labor | Unadjusted OR (95% Cl) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 193/2,459 (7.8) | 46/431 (10.7) | 0.46 (0.34–0.63) | 0.43 (0.31–0.59) |

| 37 | 222/6,253 (3.6) | 60/909 (6.6) | 0.55 (0.45–0.68) | 0.51 (0.41–0.63) |

| 38 | 247/13,284 (1.9) | 58/1,941 (3.0) | 0.66 (0.58–0.76) | 0.59 (0.51–0.68) |

| 39 | 403/23,028 (1.8) | 162/6,577 (2.5) | 0.79 (0.69–0.90) | 0.69 (0.60–0.79) |

| 40 | 363/18,163 (2.0) | 21/771 (2.7) | 0.94 (0.77–1.16) | 0.81 (0.66–1.00) |

OR, odds ratio.

Data are number of neonates with outcome/number of neonates delivered at that gestational age (%) unless otherwise specified.

The adjusted model includes the following variables: diabetes mellitus, maternal age, race–ethnicity, hypertensive disorders, neonatal sex, gestational age at delivery, and study site.

Bold indicates statistically significant findings.

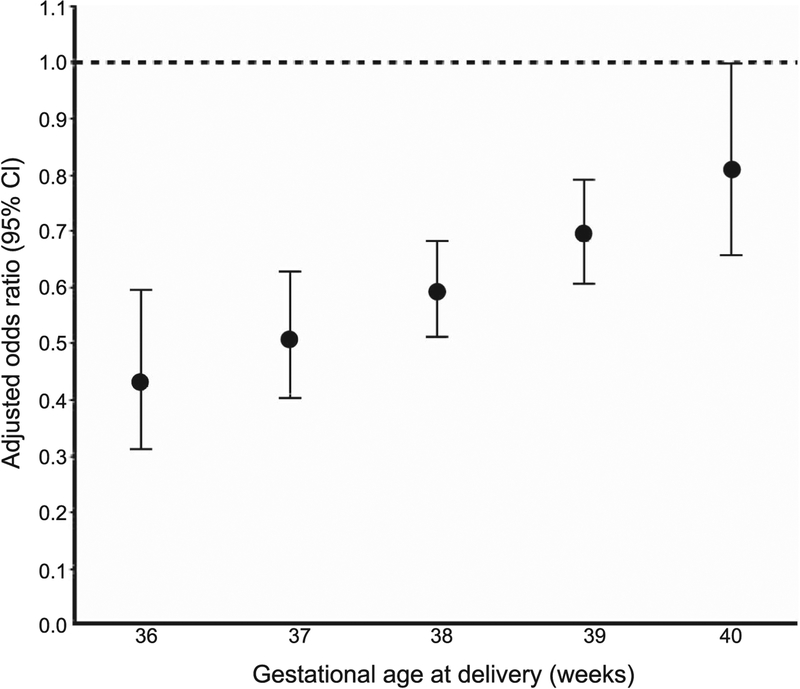

There were similar associations between labor and neonatal respiratory morbidity for women with and without diabetes (P for interaction between labor and diabetic status =.90). The association between labor and neonatal respiratory morbidity varied by gestational age at delivery (P for interaction =.01). In the adjusted model, labor (compared with no labor) was associated with lower odds of composite neonatal respiratory morbidity for neonates delivered from 36–39 weeks of gestation. Our adjusted model showed that labor was associated with the greatest reduction in the odds of respiratory morbidity for neonates delivered at 36 weeks of gestation (adjusted odds ratio 0.43, 95% CI 0.31–0.59). For all neonates delivered from 36–40 weeks of gestation, a 1-week increase in gestational age was associated with an approximate 1.2 times increase in the adjusted odds ratio for neonatal respiratory morbidity comparing labor with no labor (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Adjusted odds ratio for neonatal composite respiratory outcome by gestational age. Multivariable logistic regression models to evaluate the association between labor and the primary outcome were adjusted for diabetes mellitus, maternal age, race–ethnicity, hypertensive disorders, neonatal sex, gestational age at delivery, and study site.

DISCUSSION

We found that labor was associated with less frequent respiratory morbidity for neonates delivered from 36–39 weeks of gestation. This association was not significant for neonates delivered at 40 weeks of gestation. It is important to note that overall, the frequency of the composite outcome was low and occurred in 3.3% of neonates who did not experience labor and 2.3% of those who did experience labor. In our adjusted analyses, we determined that the magnitude of this association did not vary by the presence or absence of maternal diabetes mellitus, but did vary by gestational age. Our adjusted model showed that labor was associated with the greatest reduction in the odds of respiratory morbidity for neonates delivered at 36 weeks of gestation. However, the magnitude of this reduction in the odds diminishes for every 1-week increase in gestational age at delivery through 40 weeks of gestation. The specific components of the neonatal composite outcome that were also less frequent among neonates of women who labored were RDS and CPAP. There was no significant difference in more severe respiratory morbidity (the need for ventilator support) for neonates of mothers who labored as compared with those who did not labor. Correspondingly, for those neonates who required mechanical ventilation, the duration of ventilation was similar between groups.

The mechanisms by which labor may improve neonatal respiratory outcomes are not yet fully understood. In the guinea pig animal model, oxytocin synergizes with inflammatory pathways to enhance fetal lung maturation,19 and to trigger release of epinephrine that rapidly stimulates lung fluid clearance.20 Lung fluid clearance is essential to human neonatal adaptation and diminished fluid clearance due to low sodium-channel expression in the pulmonary epithelium has been implicated in neonatal respiratory distress.21,22

It should be noted that one strength of this study is that it evaluated outcomes as a function of labor, and not as a function of route of delivery after labor, as has been done previously.6,10–17 The analytic approach we chose and the resulting data most informs maternal and provider decision making, in that it provides information that can be used to help understand the trade-offs inherent in scheduled cesarean delivery compared with a trial of labor. However, our study design does not allow us to parse the effect of labor compared with route of delivery. Because route of delivery is an intermediate outcome between our exposure (labor) and our primary outcome (neonatal respiratory morbidity), it is not possible to adjust for route of delivery in our analysis.23 Other strengths of our analysis include the large sample size and data collection by trained research personnel. The participants included in our analysis were ethnically and racially diverse and drawn from 25 different delivery sites across the United States, which makes the findings broadly generalizable. Conversely, our study is limited, like all observational studies, in its ability to determine causality. Similarly, although we adjusted our analysis for potential known confounders, there remains the potential for unidentified confounders and biases in our analyses. In addition, we do not have precise length of labor data to evaluate a potential relationship between duration of labor and neonatal respiratory outcomes. Similarly, we do not have additional data regarding glycemic control in women with gestational or pregestational diabetes and could not assess the association between diabetic management and neonatal respiratory outcomes. Further study, particularly with regard to the mechanistic underpinnings of labor and the association with a reduction in the risk of neonatal respiratory morbidity is warranted.

In summary, in this analysis we found that labor is independently associated with lower odds of neonatal respiratory outcomes near or at term. Although our model shows that the magnitude of the association was greatest at 36 weeks of gestation, the association persisted through 39 weeks of gestation. The findings of our analysis add to the body of literature regarding labor and neonatal respiratory outcomes6,10–17 and provide an estimated reduction in the odds of neonatal respiratory morbidities that may be associated with labor. Our findings can be used to better inform clinical decision-making and patient counseling regarding a trial of labor and the potential benefits of a trial of labor in terms of lower odds of neonatal respiratory morbidity.

Supplementary Material

Table 4.

Comparisons of Birth Weight by Labor Status and Gestational Age

| Gestational Age at Delivery (wk) | Birth Weight (g) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labor | No Labor | ||

| 36 (n=2,890) | 2,803±433 | 2,803±494 | .65 |

| 37 (n=7,162) | 3,012±425 | 3,062±534 | .05 |

| 38 (n=15,225) | 3,226±421 | 3,377±487 | <.001 |

| 39 (n=29,605) | 3,388±418 | 3,501±462 | <.001 |

| 40 (n=18,934) | 3,508±414 | 3,691±526 | <.001 |

Data are mean±SD.

Missing data: 37 weeks, n=1; 38 weeks, n=1; 39 weeks, n=2.

Bold indicates significant values.

Financial Disclosure

Jennifer L. Bailit reports receiving grant support through the Ohio Perinatal Quality collaborative. Alan T. N. Tita reports receiving money paid to his institution from Novavax and Progenity Inc. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The project described was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (HD21410, HD27869, HD27915, HD27917, HD34116, HD34208, HD36801, HD40500, HD40512, HD40544, HD40545, HD40560, HD40485, HD53097, HD53118) and the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 RR024989; 5UL1 RR025764). Comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors thank Cynthia Milluzzi, RN and Joan Moss, RNC, MSN for protocol development and coordination between clinical research centers; and William A. Grobman, MD, MBA; Elizabeth Thom, PhD; Madeline M. Rice, PhD; Brian M. Mercer, MD; and Catherine Y. Spong, MD, for protocol development and oversight.

Footnotes

See Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/B492, for a list of other members of the NICHD MFMU Network.

Presented in part at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine’s 39th Annual Pregnancy Meeting, February 11–16, 2019, Las Vegas, Nevada.

Dr. Rouse, Associate Editor (Obstetrics) of Obstetrics & Gynecology, was not involved in the review or decision to publish this article.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Consortium on Safe Labor, Hibbard JU, Wilkins I, Sun L, Gregory K, Haberman S, et al. Respiratory morbidity in late preterm births. JAMA 2010;304:419–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards MO, Kotecha SJ, Kotecha S. Respiratory distress of the term newborn infant. Paediatr Respir Rev 2013;14:29–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubow JM, How HY, Habli M, Maxwell R, Sibai BM. Indications for delivery and short-term neonatal outcomes in late preterm as compared with term births. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:e30–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tita AT, Lai Y, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ, Varner MW, et al. Timing of elective repeat cesarean delivery at term and maternal perioperative outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 117(2 pt 1):280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh LI, Reddy UM, Männistö T, Mendola P, Sjaarda L, Hinkle S, et al. Neonatal outcomes in early term birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:265.e1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prefumo F, Ferrazzi E, Di Tommaso M, Severi FM, Locatelli A, Chirico G, et al. Neonatal morbidity after cesarean section before labor at 34(+0) to 38(+6) weeks: a cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29:1334–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mortier I, Blanc J, Tosello B, Gire C, Bretelle F, Carcopino X. Is gestational diabetes an independent risk factor of neonatal severe respiratory distress syndrome after 34 weeks of gestation? A prospective study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2017;296:1071–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnevier A, Brodszki J, Björklund LJ, Källén K. Underlying maternal and pregnancy-related conditions account for a substantial proportion of neonatal morbidity in late preterm infants. Acta Paediatr 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawakita T, Bowers K, Hazrati S, Zhang C, Grewal J, Chen Z, et al. Increased neonatal respiratory morbidity associated with gestational and pregestational diabetes: a retrospective study. Am J Perinatol 2017;34:1160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Indraccolo U, Pace M, Corona G, Bonito M, Indraccolo SR, Di Iorio R. Cesarean section in the absence of labor and risk of respiratory complications in newborns: a case-control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2019;32:1160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Luca R, Boulvain M, Irion O, Berner M, Pfister RE. Incidence of early neonatal mortality and morbidity after late-preterm and term cesarean delivery. Pediatrics 2009;123:e1064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun H, Xu F, Xiong H, Kang W, Bai Q, Zhang Y, et al. Characteristics of respiratory distress syndrome in infants of different gestational ages. Lung 2013;191:425–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlström A, Lindgren H, Hildingsson I. Maternal and infant outcome after caesarean section without recorded medical indication: findings from a Swedish case-control study. BJOG 2013;120:479–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman K, Woolcott C, O’Connell C, Jangaard K. Neonatal outcomes in spontaneous versus obstetrically indicated late preterm births in a nova scotia population. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34:1158–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quiroz LH, Chang H, Blomquist JL, Okoh YK, Handa VL. Scheduled cesarean delivery: maternal and neonatal risks in primiparous women in a community hospital setting. Am J Perinatol 2009;26:271–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanardo V, Simbi AK, Franzoi M, Soldà G, Salvadori A, Trevisanuto D. Neonatal respiratory morbidity risk and mode of delivery at term: influence of timing of elective caesarean delivery. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:643–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailit JL, Gregory KD, Reddy UM, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Hibbard JU, Ramirez MM, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes by labor onset type and gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:245.e1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailit JL, Grobman WA, Rice MM, Spong CY, Wapner RJ, Varner MW, et al. Risk-adjusted models for adverse obstetric outcomes and variation in risk-adjusted outcomes across hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:446.e1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair PK, Li T, Bhattacharjee R, Ye X, Folkesson HG. Oxytocin-induced labor augments IL-1beta-stimulated lung fluid absorption in fetal Guinea pig lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;289:L1029–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norlin A, Folkesson HG. Ca(2+)-dependent stimulation of alveolar fluid clearance in near-term fetal Guinea pigs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;282:L642–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helve O, Pitkänen OM, Andersson S, O’Brodovich H, Kirjavainen T, Otulakowski G. Low expression of human epithelial sodium channel in airway epithelium of preterm infants with respiratory distress. Pediatrics 2004;113:1267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helve O, Pitkänen O, Janér C, Andersson S. Pulmonary fluid balance in the human newborn infant. Neonatology 2009;95:347–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ananth CV, Schisterman EF. Confounding, causality, and confusion: the role of intermediate variables in interpreting observational studies in obstetrics. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.