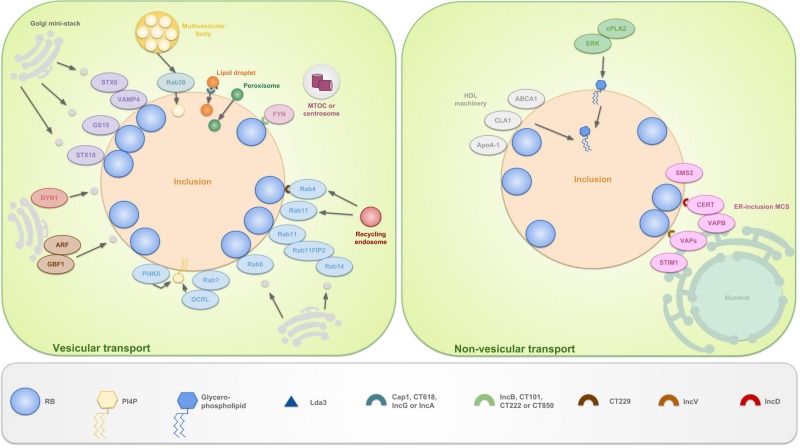

FIGURE 5.

Schematic representation of the vesicular and non-vesicular pathways, employed by C. trachomatis. The inclusion selectively interacts with organelles in the peri-Golgi region by means of vesicular and non-vesicular pathways in order to sequester eukaryotic lipids for chlamydial development and survival. These lipids include sphingolipids, cholesterol and glycerophospholipids. The hijacking of lipids derived from the Golgi apparatus is facilitated by the positioning of mini-stacks around the inclusion. Sphingomyelin and cholesterol are attained via interception of exocytic vesicles, fragmented from these mini-stacks. Capturing of vesicles is done by hijacking Golgi-associated Rabs (such as Rab6, 11 and 14), which promote selective interaction and/or fusion between several host vesicles. Rab4 and 11 also mediate interactions with the transferrin slow-recycling pathway in order to acquire iron. Recruitment of these Rabs is done by chlamydial Incs, e.g., CT229 recruits Rab4. Rab11 on his turn recruits Rab11FIP2 and together these recruit Rab14. In addition to trafficking, Rabs also promote vesicle fusion by recruiting lipid kinases such as inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase OCRL1, a Golgi-localized enzyme and PI4KIIα. Both produce the Golgi-specific lipid PI4P and enrichment of the latter is considered a strategy to disguise the inclusion as a specialized compartment of the Golgi apparatus. Furthermore, chlamydiae interact with trans-Golgi STX6 and STX10, VAMP4 and GS15. These also regulate the acquisition of nutrients from the Golgi exocytotic pathway. Moreover, GBF1, a regulator of Arf1-dependent vesicular trafficking within the early secretory pathway is employed. Finally, growth of C. trachomatis is depending on interactions with DYN1, a large GTPase that induces scission of vesicles from, among others, the Golgi apparatus. Whether or not FYN kinase regulates vesicle-mediated trafficking is currently unknown. However, it is hypothesized that FYN mediates linkage of the inclusion to the microtubule network, thereby intersecting sphingomyelin-containing vesicles that traffic along the microtubules. LDs, peroxisomes and MVBs also represent useful sources for eukaryotic lipids and get translocated fully into the inclusion. LDs are ER-derived storage organelles for neutral lipids or long chain fatty acids. Lda3 gets translocated to the host cytosol after which it links cytoplasmic LDs to the inclusion membrane. Furthermore, it was suggested that IncA might mark the entry sites for LDs at the inclusion membrane. The mechanisms of peroxisome and MVB uptake are still unclear, although Rab39 was shown to participate in the delivery of MVBs to the inclusion. ER derived sphingomyelin on the other hand is acquired via non-vesicular pathways. The existence of ER-inclusion MCSs was shown in which CERT, ER-resident protein VAPB, SMS2 and ER calcium sensor STIM1 are enriched. CERT is proven to be recruited to these MCSs via direct interaction with IncD, which in turn leads to the binding of CERT with VAPB. It is believed that CERT and VAPB participate to the non-vesicular trafficking of ceramide, the precursor of sphingomyelin, from the ER to the inclusion, after which ceramide is further converted into sphingomyelin by SMS2. The role of STIM1 remains unanswered. Besides CERT also IncV is able to interact with VAPs, possibly assisting in ER-inclusion tethering. Another non-vesicular pathway involves the co-opting of the host cell lipid transport system involved in the formation of HDLs. HDL is formed when cholesterol and phospholipids are transported to extracellular ApoA-1 by the lipid binding proteins ABCA1 and ABCG1 and CLA1. ABCA1, CLA1 and ApoA-1 are shown to be localized at the inclusion membrane. Lastly, PI and PC are acquired via another non-vesicular pathway, mediated by ERK and cPLA2.