Abstract

Background: Despite a reduction in the prevalence of vaccine-preventable types of human papillomavirus (HPV), attributed to increased HPV vaccine uptake, HPV continues to be a major cause of cancer in the United States.

Methods: We assessed factors associated with self-reported HPV vaccine uptake, HPV vaccination effectiveness, using DNA testing to assess HPV types 16 and/or 18 (HPV 16/18) positivity, and patterns of HPV vaccination in 375 women aged 21–29 years who were eligible to receive catch-up vaccination, using baseline data collected from March 2012 to December 2014 from a randomized controlled trial evaluating a novel approach to cervical cancer screening.

Results: More than half (n = 228, 60.8%) of participants reported receipt of at least one HPV vaccine dose and 16 (4.3%) tested positive for HPV 16/18 at baseline. College-educated participants were four times more likely to have been vaccinated than those reporting high school education or less. 56.5% of HPV-vaccinated participants reported first dose after age 18 and 68.4% after first vaginal intercourse. Women vaccinated after age 18 and women vaccinated after first vaginal intercourse were somewhat more likely to be infected with HPV 16/18 infection compared with women vaccinated earlier, but these associations did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusions: HPV vaccination is common among college-educated women in the catch-up population but less common among those without college education. Contrary to current guidelines, catch-up females frequently obtain HPV vaccination after age 18 and first vaginal intercourse. Women without a college education represent an ideal population for targeted HPV vaccination efforts that emphasize vaccination before sexual debut.

Keywords: HPV, vaccination, human papillomavirus, correlates, catch-up population

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, with ∼79 million Americans currently infected.1 Despite a substantial reduction in the prevalence of vaccine-type HPV attributed to increased HPV vaccine availability,2 HPV continues to be a major public health threat in the United States, causing ∼17,600 cancers in women and 9300 cancers in men each year.1

HPV vaccines have been available since 2006 for individuals aged 9–26 years. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers 11- to 12-year-olds the target age group for vaccination, with females aged 13–26 in the “catch-up” phase, meaning they are outside of the target age group for disease prevention but may still benefit from HPV vaccination.3 Initial guidelines recommended three doses, given at 0, 1–2, and 6-month increments, for all ages, However, based on subsequent research demonstrating sufficient efficacy with just two doses in children <15 years,4–8 CDC's 2014 guidelines were updated to permit a two-dose schedule with 6–12 months between doses if initiated before age 15.3 In the catch-up population, ongoing research suggests that two doses may be equally effective as three,6,8,9 and even one dose may be effective at preventing vaccine-type HPV.9–11

Among both younger12–17 and catch-up females,18–21 prior studies have demonstrated that there are demographic differences between those who are and are not vaccinated, although reports have been inconsistent. To continue to increase HPV vaccination uptake, increased research is needed to shed light on these differences to inform potential targeted outreach efforts. Literature surrounding factors that influence vaccine effectiveness among catch-up females, including age at first dose, timing between doses, and age of first vaginal intercourse in relation to vaccination, is also limited. Existing research has largely demonstrated that HPV vaccination among catch-up females is effective and leads to population-level herd effects against vaccine-type HPV.22–25 However, most of this research has been conducted outside of the United States and does not include sexual debut in relation to vaccination, a key factor for this population. The most recent U.S.-based research did not only find the HPV vaccine to be effective among older females, but also did not examine sexual debut as a factor of interest.26 More research inside the United States that includes sexual debut data is needed to better understand vaccine effectiveness in this population.

Using baseline data from a cervical cancer screening clinical trial conducted from 2012 to 2014 among 21- to 29-year-old women who would have been eligible for catch-up vaccination, based on their age and timing of HPV vaccine availability, our study had two primary aims: (1) assess factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake before study enrollment and (2) assess the effectiveness of HPV vaccination against HPV types 16 and/or 18 (HPV 16/18). In addition, we sought to characterize patterns related to HPV vaccination receipt, including age at first dose, number of doses received, timing between doses, and age at first vaginal intercourse relative to vaccine series initiation. We further aimed to examine whether either age at first dose or vaccination before first vaginal intercourse were associated with detection of HPV 16/18. Finally, we aimed to examine the association between number of doses received and detection of HPV 16/18.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This study employed a cross-sectional design, using baseline data collected from the HOPE (Home HPV or Pap Examination) study. The HOPE study was a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded randomized controlled trial based out of the University of Washington (UW), with the primary aim of assessing the acceptability and effectiveness of at home self-collected vaginal HPV screening compared with traditional Pap-based cervical cancer screening.27 Participants were recruited through multiple methods, including through in-person invitation when they presented to two UW clinics for routine cervical cancer screening, direct mailing to UW students and staff, local newspaper advertisements, local web advertisements, and community posted flyers in the Seattle area.27 Women who were <21 years, received treatment for cervical dysplasia within 3 years, received colposcopy of the cervix within 2 years, received a Pap test within 1 year, had undergone a hysterectomy, were pregnant at time of enrollment, or who were immunocompromised were excluded from participation.27 The HOPE study enrolled 1819 women between 21 and 65 years from March 2012 to December 2014. For the present analysis, we excluded study participants who were not randomized to the home HPV testing arm (n = 910), as HPV testing was not performed routinely in the standard care arm, women who were ≥30 years (n = 479) at baseline, as they were ineligible for HPV vaccination based on the timing of commercial availability of HPV vaccines, and women with missing HPV vaccination history data (n = 55). Our final study population included 375 individuals.27

Study participants were asked to self-report demographics, HPV vaccination status, date of receipt of each vaccination dose, and other characteristics through a self-administered baseline questionnaire. Women randomized to the at-home testing study arm were given a self-collection kit, including two individually packed sterile Dacron tipped swabs for sample collection and one polypropylene specimen transport tube with shipping and packing materials, to obtain self-collected samples of vaginal cells. After the vaginal sample was collected using the swab and deposited into the transport tube, study participants wrote the date of sample collection on the tube and shipped their samples, along with their completed baseline questionnaires, to the laboratory, where HPV DNA of self-collected specimens was evaluated by Hybrid Capture.27 The Hybrid Capture provided information on whether the samples were positive for any of 13 high risk (HR)-HPV types. Samples that tested positive for HPV were assessed for 14 individual HPV types by a Luminex-based liquid bead microarray assay (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68).27 Of the 103 women who were found to be infected with HPV at baseline, 95 were typed using Luminex-based liquid bead microarray assay and 8 samples did not undergo HPV typing.27

Predictors

Predictors of interest for aim 1 were race (white, black, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, other), current age (21–23, 24–26, 27–29), highest level of education completed (high school or less, associate or technical degree, bachelor's degree, graduate school), ever use of hormonal contraception (yes, no), and age at first vaginal intercourse in years (9–15, 16–18, 19–21, 22–27), as prior research has demonstrated associations between these predictors and HPV vaccination status.12–18,28

The primary predictor of interest for aim 2 was self-reported HPV vaccination. Individuals reporting receipt of at least one dose were considered vaccinated (n = 228) and individuals reporting no doses were considered unvaccinated (n = 147). We also categorized vaccination status by number of doses received (0, 1, 2, 3) to perform subanalyses examining the association between number of doses and HPV 16/18 DNA detection. To assess dosing patterns associated with HPV vaccination we separately assessed age at first dose (12–18, 19–26), months between doses (6 or fewer, 7–12, 13–18, 20 or more) and timing of vaccination in relation to first vaginal intercourse (prior, same year, after).

We computed four predictor variables. These included age at first dose, months between doses 1 and 2, months between doses 2 and 3, and timing of vaccination in relation to first vaginal intercourse. To compute age at first dose, we calculated the number of months between self-reported date of first dose and the study enrollment date. We then converted months to years and subtracted the number of years from baseline age to estimate the age that study participants received their first HPV vaccination dose. When data were missing for month and/or day at first dose, we imputed July and/or the first of the month.

To compute months between doses, we subtracted self-reported dose receipt dates and converted time into months. For these variables, we did not impute missing data, as the specific date was necessary to accurately characterize this information. To compute vaccination in relation to first vaginal intercourse, we used age at first vaccination dose and age at first vaginal intercourse. If age at first dose was less than age at first vaginal intercourse, women were coded as vaccinated before first intercourse; if age at first dose was greater than age at first intercourse, women were coded as vaccinated after first intercourse; otherwise, women were coded as vaccinated the same year as first intercourse.

Outcomes

The aim 1 outcome was self-reported HPV vaccination status (one or more doses, no doses). HPV 16 and/or 18 positivity, determined through Luminex-based liquid bead microarray assay, was the outcome for aim 2 and subanalyses.

Statistical analysis

We used multivariable logistic regression to obtain crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between each predictors of interest (age, race, education, use of hormonal contraception, and age at first vaginal intercourse) and HPV vaccination. Race was dichotomized as white versus other due to small sample sizes for other racial categories. Our adjusted statistical model included all predictors of interest, determined a priori, to correct for potential confounding.

To evaluate the association between self-reported vaccination status and HPV 16/18 prevalence, we calculated ORs and 95% CIs using logistic regression. We repeated this analysis using number of doses as the exposure. Logistic regression was also used for subanalyses.

All research activities were approved by the trial data safety and monitoring board, and the UW (No. 7489 approved July 20, 2011 and No. 9028 approved November 20, 2013) and University of Minnesota (No. 1109M04321 approved October 5, 2011) Institutional Review Boards. All analyses were performed using STATA 14.29

Results

Of 375 subjects, 228 (60.8%) reported receipt of at least one dose of the HPV vaccine before study entry (Table 1). Compared with unvaccinated women, vaccinated women tended to be younger, white, hormonal contraceptive users, and more highly educated. Although the greatest proportion of women in both groups reported first vaginal intercourse at 16–18 years, unvaccinated women were more likely to be early as well as late initiators.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Females Aged 21–29 Enrolled in the Home HPV or Pap Examination Study, 2012–2014

| Characteristics | Vaccinateda | Unvaccinated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 375d | n = 228 | 60.8% | n = 147 | 39.2% |

| Age, years | ||||

| 21–23 | 92 | 40.4 | 46 | 31.3 |

| 24–26 | 89 | 39.0 | 52 | 35.4 |

| 27–29 | 47 | 20.6 | 49 | 33.3 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 169 | 74.5 | 93 | 63.3 |

| Black | 8 | 3.5 | 9 | 6.1 |

| Asian | 29 | 12.8 | 26 | 17.7 |

| Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.4 | 4 | 2.7 |

| Native American | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Otherb | 19 | 8.4 | 15 | 10.2 |

| Hispanic | 23 | 10.3 | 16 | 11.1 |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 10 | 4.4 | 18 | 12.2 |

| Associate or technical degree | 75 | 32.9 | 52 | 35.4 |

| Bachelor's degree | 77 | 33.8 | 38 | 25.9 |

| Graduate school | 66 | 29.0 | 39 | 26.5 |

| Annual household income, $ | ||||

| <10,000 | 60 | 36.1 | 45 | 42.1 |

| 10,000–24,999 | 39 | 23.5 | 25 | 23.4 |

| 25,000–49,999 | 39 | 23.5 | 21 | 19.6 |

| 50,000 or more | 28 | 16.9 | 16 | 15.0 |

| Age at first vaginal intercourse, years | ||||

| 9–15 | 35 | 16.3 | 32 | 22.9 |

| 16–18 | 119 | 55.4 | 58 | 41.4 |

| 19–21 | 47 | 21.9 | 30 | 21.4 |

| 22–27 | 14 | 6.5 | 20 | 14.3 |

| History of any sexually and non-sexually transmitted infectionsc (STI) | 98 | 43.2 | 66 | 44.9 |

| History of STI | 21 | 14.0 | 17 | 17.4 |

| History of yeast vaginitis | 50 | 23.0 | 24 | 17.4 |

| History of bacterial vaginosis | 29 | 13.7 | 20 | 14.6 |

| Use of any hormonal contraception | ||||

| Yes | 192 | 84.2 | 111 | 75.5 |

| No | 34 | 14.9 | 35 | 23.8 |

| Age at first Pap, years | ||||

| 12–15 | 18 | 7.9 | 12 | 8.2 |

| 16–18 | 74 | 32.5 | 49 | 33.3 |

| 19–21 | 92 | 40.4 | 38 | 25.9 |

| 22–26 | 44 | 19.3 | 48 | 32.7 |

Vaccinated is defined as having received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine.

Other category includes those who self-reported race as Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Russian, Caribbean, Filipina, and unknown.

Sexually and non-sexually transmitted infections include yeast vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis, cervicitis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital herpes, cervical warts, and vulvar or vaginal warts.

Data may not add up to entire sample size due to missing data. Missing data include race (0.3%), Latina (1.9%), household income (27.2%), age at first vaginal intercourse (5.3%), history of sexually or nonsexually transmitted infection (0.27%), history of sexually transmitted infection (33.9%), history of yeast vaginitis (5.3%), history of bacterial vaginosis (6.9%), and use of hormonal contraception (0.8%).

HPV, human papillomavirus; STI, sexually transmitted infections.

In univariate analyses, we detected statistically significant differences in vaccination status by age, race, education level, and ever use of hormonal contraception (Table 2). Younger women, white women, women with higher levels of education, and women who had reported use of hormonal contraception at any point in their lives had statistically significantly higher odds of being vaccinated. After adjustment for all predictors of interest, the associations between both education and vaccination status and age and vaccination status strengthened. Specifically, in our multivariable analysis, individuals with higher levels of education, reporting bachelor's or graduate level education, had more than four times higher odds of being vaccinated as those reporting high school or less as their highest level of education. Women aged 27–29 had a three times lower odds (OR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.17–0.64) of being vaccinated compared with women aged 21–23 years. In the final multivariable model, the association between race and vaccination status was attenuated, whereas the association between ever use of hormonal contraception and vaccination status remained similar. However, neither of these associations was statistically significant after adjustment. The association between age at first vaginal intercourse and HPV vaccination status was also not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Associations Between Risk Factors and Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Status Among Females Aged 21–29

| Risk factor | Vaccinateda | Total | Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted ORb,c | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 375f | N = 228 | 60.8% | N | ||||

| Age, yearsd | |||||||

| 21–23 | 92 | 66.7 | 138 | 1.0 | Ref. | 1.0 | Ref. |

| 24–26 | 89 | 63.1 | 141 | 0.86 | 0.52–1.40 | 0.59 | 0.32–1.09 |

| 27–29 | 47 | 49.0 | 96 | 0.48 | 0.28–0.82 | 0.33 | 0.17–0.64 |

| Racee | |||||||

| White | 169 | 64.5 | 262 | 1.0 | Ref. | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Other | 58 | 51.8 | 112 | 0.59 | 0.38–0.93 | 0.79 | 0.48–1.30 |

| Educationd | |||||||

| High school or less | 10 | 35.7 | 28 | 1.0 | Ref. | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Associate or technical degree | 75 | 59.1 | 127 | 2.60 | 1.11–6.07 | 2.08 | 0.81–5.34 |

| Bachelor's degree | 77 | 67.0 | 115 | 3.65 | 1.54–8.66 | 4.15 | 1.53–11.26 |

| Graduate school | 66 | 62.9 | 105 | 3.05 | 1.28–7.26 | 4.44 | 1.54–12.82 |

| Age at first vaginal intercourse, years | |||||||

| 9–15 | 35 | 52.2 | 67 | 1.0 | Ref. | 1.0 | Ref. |

| 16–18 | 119 | 67.2 | 177 | 1.88 | 1.06–3.33 | 1.45 | 0.77–2.72 |

| 19–21 | 47 | 61.0 | 77 | 1.43 | 0.74–2.78 | 1.14 | 0.55–2.39 |

| 22–27 | 14 | 41.2 | 34 | 0.64 | 0.28–1.47 | 0.52 | 0.16–1.50 |

| Ever use of hormonal contraception | |||||||

| No | 34 | 49.3 | 69 | 1.0 | Ref | 1.0 | Ref |

| Yes | 192 | 63.4 | 303 | 1.78 | 1.05–3.01 | 1.78 | 0.94–3.37 |

Vaccination is defined as having at least one dose of the HPV vaccination series.

The adjusted model excludes 24 observations because of missing data.

Model is adjusted for all predictors of interest, including age, race, education, ever use of hormonal contraception, and age at first vaginal intercourse.

Statistically significant ORs after adjustment for at least one category.

Strata were collapsed to increase power.

Data may not add up to entire sample size due to missing data. Missing data include race (0.3%), age at first vaginal intercourse (5.3%), and use of hormonal contraception (0.8%).

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Almost half of participants reported three doses of HPV vaccine (Table 3). Among vaccinated participants, 56.5% reported their first dose after age 18. Extended intervals between doses was common, with 42.9% and 38.2%, reporting 7–12 months between doses 1 and 2 and doses 2 and 3, respectively. The majority of vaccinated participants (68.4%) reported receiving their first dose after first vaginal intercourse.

Table 3.

Self-Reported Vaccine-Related Characteristics of Females Aged 21–29 Enrolled in the Home HPV or Pap Examination Study, 2012–2014

| Characteristics | nb | % |

|---|---|---|

| N = 375 | ||

| No. of doses received | ||

| 0 | 147 | 39.2 |

| 1 | 18 | 4.8 |

| 2 | 34 | 9.1 |

| 3 | 176 | 46.9 |

| Age at first dose, yearsa | 200 | |

| 12–15 | 19 | 9.5 |

| 16–18 | 68 | 34.0 |

| 19–21 | 57 | 28.5 |

| 22–26 | 56 | 28.0 |

| Months between dose 1 and 2a | 119 | |

| 6 or fewer | 32 | 26.9 |

| 7–12 | 51 | 42.9 |

| 13–19 | 22 | 18.5 |

| 20 or more | 14 | 11.8 |

| Months between dose 2 and 3a | 102 | |

| 6 or fewer | 14 | 13.7 |

| 7–12 | 39 | 38.2 |

| 13–19 | 31 | 30.4 |

| 20 or more | 18 | 17.7 |

| Receipt of dose 1 relative to first vaginal intercoursea | 215 | |

| Prior | 45 | 20.9 |

| Same year | 23 | 10.7 |

| After | 147 | 68.4 |

Includes only those who were vaccinated for HPV (N = 228).

Data may not add up to entire sample size due to missing data. Missing data include age at first dose (12.3%), months between dose 1 and 2 (39.9%), months between dose 2 and 3 (32.5%), and receipt of dose 1 relative to first vaginal intercourse (5.7%). Missing data for months between dose 1 and 2 and months between dose 2 and 3 exclude women who did not receive a second or third dose, respectively.

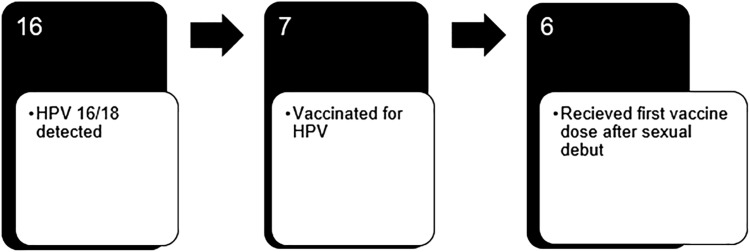

HPV 16/18 was detected in 16 (4.3%) women at baseline, 9 of whom were unvaccinated, 1 of whom received their first vaccine dose before and 6 of whom received their first dose after first vaginal intercourse (Fig. 1). Overall vaccine efficacy was 49.2% among our study population. Detection of HPV 16/18 was somewhat increased among unvaccinated (6.3%) compared with vaccinated (3.2%) women but this did not attain statistical significance (Table 4). Similarly, we did not detect any statistically significant differences in detection of HPV types 16/18 by number of doses received although there was a trend toward increasing HPV 16/18 detection with increasing number of doses, as HPV 16/18 was detected in 5.6% of women with one dose, 3.1% of women with two doses, and 2.9% of women with three doses. Furthermore, although statistically nonsignificant, HPV 16/18 was somewhat more likely detected in women with a first dose between ages 19–26 (3.7%) compared with ages 12–18 (1.2%). Finally, HPV 16/18 detection was somewhat higher in those vaccinated after (4.2%) compared with before (2.3%) first vaginal intercourse, although this again did not attain statistical significance.

FIG. 1.

Six of the seven HPV vaccinated women in whom HPV 16/18 was detected received their first vaccine dose after sexual debut. HPV, human papillomavirus; HPV 16/18, HPV types 16 and/or 18.

Table 4.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Detection of HPV Types 16 and/or 18, Among Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Women Aged 21–29

| N = 364 | HPV 16/18 detected | Crude OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | n = 16 | N | % | ||

| HPV vaccination status | |||||

| Vaccinateda | 7 | 221 | 3.2 | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Not vaccinated | 9 | 143 | 6.3 | 2.05 | 0.75–5.64 |

| No. of doses | |||||

| 0 | 9 | 143 | 6.3 | 2.23 | 0.73–6.81 |

| 1 | 1 | 18 | 5.6 | 1.95 | 0.22–17.70 |

| 2 | 1 | 32 | 3.1 | 1.07 | 0.12–9.48 |

| 3 | 5 | 171 | 2.9 | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Age at dose 1, yearsb,c,d | |||||

| 12–18 | 1 | 85 | 1.2 | 1.0 | Ref. |

| 19–26 | 4 | 109 | 3.7 | 3.20 | 0.35–29.17 |

| Receipt of dose 1 relative to first vaginal intercourseb,c,d | |||||

| Prior | 1 | 44 | 2.3 | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Same year | 0 | 23 | 0 | — | — |

| After | 6 | 142 | 4.2 | 1.89 | 0.22–16.20 |

Vaccinated is defined as having received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine.

Includes only those who were vaccinated for HPV (N = 221).

Sample size too small to adjust for multivariable assessment.

Data may not add up to entire sample size due to missing data. Missing data include age at first dose (46.7%) and receipt of dose 1 relative to first vaginal intercourse (42.6%).

HPV 16/18, HPV types 16 and/or 18.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that among females aged 21–29 years who were eligible for catch-up HPV vaccination, those who were younger and college-educated had a higher odds of being vaccinated than females who were older or received high school or less education. Nearly half of our participants reported having received all three recommended doses. More than two-thirds of our catch-up study population reported first vaginal intercourse before HPV vaccine initiation; however, age at first intercourse was not associated with vaccination status. Moreover, most women did not receive their HPV vaccinations according to the recommended dosing schedule.

Catch-up vaccination appeared to be effective among women receiving vaccination before age 18, receiving two or three doses, and women vaccinated before sexual activity. Although our results were statistically nonsignificant and vaccine efficacy was 49.2% overall, six of the seven women who were vaccinated for HPV and tested positive for HPV 16/18 reported their first dose after first intercourse. Our data suggest similar protection among women who have obtained two and three doses, but a substantial decrease in protection among women who had received only one dose.

Prior research on the association between education and HPV vaccination has focused on adolescent females, included only parental educational status, rather than patient educational status, and reported inconsistent findings. For instance, several studies found no significant difference between parental education and HPV vaccination in their children,30–34 whereas others reported higher vaccination prevalence among more educated parents15,35 or lower vaccination prevalence among more educated parents,36 yet none of these studies include females >18 years. Our study adds to the literature by including females >18 years and demonstrating that, among women recruited for a research trial, higher educational attainment is associated with higher HPV vaccination uptake.

Previous studies that have included women >18 years have found that this age group is less likely to be vaccinated than adolescent women14,37 and that among females 18–26, older women within this age group are less likely to be vaccinated.14 Moreover, prior research, including the HPV vaccination catch-up population, has demonstrated differences in vaccination uptake and completion by race, with white race being associated with higher uptake and completion of the series than other racial categories.12,17,37 These findings are consistent with our study results.

Compared with prior studies evaluating HPV vaccination and dosing patterns outside of clinical trials and including women in the catch-up population, women in our study had a similar prevalence of vaccine series completion but a lower prevalence of on-time series completion.37–39 Similar to our study, many of these studies recruited participants from university-based clinical settings and included women in their 20s.14,38,39 However, unlike our study, most of these studies include adolescent participants.14,38,39 When compared with studies that utilize nonuniversity-based sampling frames, we still observe comparable results.2,37,40,41 Our findings suggesting that older age and receipt of the first dose of the HPV vaccine series after first vaginal intercourse are associated with higher detection of HPV 16/18 are consistent with findings from clinical trials that included a catch-up population42–45; however, these associations are understudied outside of trial settings.

Our findings add to the increasing body of research demonstrating differences between females who are and are not vaccinated. Although prior studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the HPV vaccine, few have assessed HPV vaccine effectiveness among women outside of efficacy trials,2,46–48 and those that exist vary greatly by research methods and participant demographics. Of these prior studies, two used data from CDC's National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES),2,47 one included females recruited via the Internet,46 and one studied inner-city adolescent females.48 Among the limited existing research, our vaccine effectiveness results are lower, with one NHANES study reporting effectiveness as high as 82% with only one dose.2 Similar to our study, this study relied on self-report data; however, this effectiveness estimate included adolescent women, who have different risk factors, including lifetime number of sexual partners and exposure to sexually transmitted infections, than women in the catch-up population.

One strength of our study was the inclusion of extensive data on sexual experiences, which provided real-world context that few prior studies have been able to examine. Through a combination of self-report data and HPV testing data, we were able to assess the association between HPV 16/18 and vaccination before versus after first vaginal intercourse, which prior observational studies have not assessed. Furthermore, we were able to observe HPV dosing patterns that are likely indicative of HPV patterns among women in their 20s presenting to a health clinic for cervical cancer screening.

Although use of self-report data was necessary to collect the data needed on prior sexual experiences and HPV vaccination dosing patterns, use of self-report data is also a substantial limitation of this study as it is subject to both recall49 and social desirability biases.50 Specifically, reliance on self-report data led to missing, and potentially misreported, data, on the number and dates of HPV vaccination doses. Even after imputing data for month and day of vaccination doses, we were unable to account for the 46.7% of missing data on date of first vaccine dose that our study population did not report. The proportion of missing data differed between those with and without HPV 16/18, which may have led to misclassification of these exposures.

Another primary limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, precluding assessment of protection against incident HPV. Furthermore, due to our small sample size of women who tested positive for HPV 16/18, we were underpowered to generate statistically significant associations related to HPV16/18-detection. This was a consequence of conducting a secondary analysis among data that were originally intended to answer a different study question. An additional limitation was the use of multiple recruitment methods for study participants, which increased our sample size but decreased our ability to generalize our findings to a specific population. Finally, the majority of our study participants were white and a large proportion of our nonwhite study participants were Asian. Although this distribution is reflective of the racial distribution in Seattle and King County, we were unable to assess the influence of particular racial categories on vaccination status as prior studies have demonstrated.

Our study demonstrates significant potential to increase HPV vaccine uptake among females who are less educated or in their early 20s. Nearly 40% of our study population was unvaccinated at baseline, even though most were still <26 years and within CDC's recommended vaccination age group. Targeted HPV vaccination campaigns could prevent vaccine-type HPV and subsequent cancer among these groups of women.

Our findings further support that targeting females before sexual debut is necessary for maximum protection against vaccine-type HPV. Among vaccinated study participants, we only detected HPV 16/18 for one individual who was vaccinated before first vaginal intercourse. However, the majority of our vaccinated study population received their first dose after first intercourse. Although opportunistic vaccination among the catch-up population is common and lends itself to imperfect vaccination circumstances, improving outreach efforts for HPV vaccination among females before they experience sexual debut has the potential to substantially decrease vaccine-type HPV infection.

Our findings indicate widespread loss to follow-up for the HPV vaccination series, with approximately a quarter of our vaccinated study participants not completing the full series. These results highlight the need for continued education and interventions to encourage HPV series completion among the catch-up population, as completing the recommended dosing schedule is important for maximum vaccine-type HPV protection. More research is needed to assess whether reduced dosing schedules will adequately protect individuals from vaccine-type HPV, especially among catch-up phase populations who may be less likely to adhere to guideline-recommended schedules.

Conclusion

HPV vaccination is common among college-educated women in the catch-up population but less common among those without college education. Contrary to current guidelines, women in the catch-up population frequently obtain HPV vaccination after age 18 and first vaginal intercourse. Women without a college education represent an ideal population for targeted HPV vaccination efforts that emphasize vaccination before sexual debut.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by National Institutes of Health NIH, R01, grant number R01-CA-15469 and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration's Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), grant number T76MC00011. This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov NCT01550783. The study was conducted in Seattle, WA.

Author Disclosure Statement

There are no competing financial interests to report.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV)—Know the facts. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015. Available at: www.cdc.gov/std/hpv stdfact-hpv.htm Accessed April9, 2016

- 2. Markowitz L, Hariri S, Lin C, et al. Reduction in human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence among young women following HPV vaccine introduction in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2003–2010. J Infect Dis 2013;208:385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV vaccine recommendations. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp recommendations.html Accessed April1, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donken R, Schurink-Van't Klooster TM, Schepp RM, et al. Immune responses after 2 versus 3 doses of HPV vaccination up to 4½ years after vaccination: An observational study among Dutch routinely vaccinated girls. J Infect Dis 2017;215:359–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dobson SR, McNeil S, Dionne M, et al. Immunogenicity of 2 doses of HPV vaccine in younger adolescents vs 3 doses in young women: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309:1793–1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kreimer AR, Struyf F, Del Rosario-Raymundo MR, et al. Efficacy of fewer than three doses of an HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: Combined analysis of data from the Costa Rica Vaccine and PATRICIA Trials. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:775–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. LaMontagne DS, Mugisha E, Pan Y, et al. Immunogenicity of bivalent HPV vaccine among partially vaccinated young adolescent girls in Uganda. Vaccine 2014;32:6303–6311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Romanowski B, Schwarz TF, Ferguson LM, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered as a 2-dose schedule compared with the licensed 3-dose schedule: Results from a randomized study. Hum Vaccin 2011;7:1374–1386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Safaeian M, Porras C, Pan Y, et al. Durable antibody responses following one dose of the bivalent human papillomavirus L1 virus-like particle vaccine in the Costa Rica Vaccine Trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6:1242–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sankaranarayanan R, Prabhu PR, Pawlita M, et al. Immunogenicity and HPV infection after one, two, and three doses of quadrivalent HPV vaccine in girls in India: A multicentre prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:67–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Markowitz LE, Drolet M, Perez N, Jit M, Brisson M. Human papillomavirus vaccine effectiveness by number of doses: Systematic review of data from national immunization programs. Vaccine 2018;36:4806–4815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chao C, Velicer C, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ. Correlates for completion of 3-dose regimen of HPV vaccine in female members of a managed care organization. Mayo Clin Proc 2009;84:864–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cook RL, Zhang J, Mullins J, et al. Factors associated with initiation and completion of human papillomavirus vaccine series among young women enrolled in Medicaid. J Adolesc Health 2010;47:596–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dempsey A, Cohn L, Dalton V, Ruffin M. Worsening disparities in HPV vaccine utilization among 19–26 year old women. Vaccine 2011;29:528–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jeudin P, Liveright E, Del Carmen MG, Perkins RB. Race, ethnicity, and income factors impacting human papillomavirus vaccination rates. Clin Ther 2014;36:24–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kessels SJ, Marshall HS, Watson M, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Reuzel R, Tooher RL. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: A systematic review. Vaccine 2012;30:3546–3556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okafor C, Hu X, Cook RL. Racial/ethnic disparities in HPV vaccine uptake among a sample of college women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2015;2:311–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Canfell K, Egger S, Velentzis LS, et al. Factors related to vaccine uptake by young adult women in the catch-up phase of the National HPV Vaccination Program in Australia: Results from an observational study. Vaccine 2015;33:2387–2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Conroy K, Rosenthal SL, Zimet GD, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake, predictors of vaccination, and self-reported barriers to vaccination. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1679–1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rondy M, van Lier A, van de Kassteele J, Rust L, de Melker H. Determinants for HPV vaccine uptake in the Netherlands: A multilevel study. Vaccine 2010;28:2070–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thompson EL, Vamos CA, Vázquez-Otero C, Logan R, Griner S, Daley EM. Trends and predictors of HPV vaccination among U.S. College women and men. Prev Med 2016;86:92–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drolet M, Laprise JF, Brotherton JM, et al. The impact of human papillomavirus catch-up vaccination in Australia: Implications for introduction of multiple age cohort vaccination and postvaccination data interpretation. J Infect Dis 2017;216:1205–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Machalek DA, Garland SM, Brotherton JM, et al. Very low prevalence of vaccine human papillomavirus types among 18-to 35-year old Australian women 9 years following implementation of vaccination. J Infect Dis 2018;217:1590–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Munro A, Gillespie C, Cotton S, et al. The impact of human papillomavirus type on colposcopy performance in women offered HPV immunisation in a catch-up vaccine programme: A two-centre observational study. BJOG 2017;124:1394–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith MA, Canfell K, Brotherton JM, Lew JB, Barnabas RV. The predicted impact of vaccination on human papillomavirus infections in Australia. Int J Cancer 2008;123:1854–1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Silverberg MJ, Leyden WA, Lam JO, et al. Effectiveness of catch-up human papillomavirus vaccination on incident cervical neoplasia in a US health-care setting: A population-based case-control study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018;2:707–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mao C, Kulasingam SL, Whitham HK, Hawes SE, Lin J, Kiviat NB. Clinician and patient acceptability of self-collected human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26:609–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gross TT, Laz TH, Rahman M, Berenson AB. Association between mother-child sexual communication and HPV vaccine uptake. Prev Med 2015;74:63–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Allen JD, Othus MK, Shelton RC, et al. Parental decision making about the HPV vaccine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:2187–2198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gerend MA, Weibley E, Bland H. Parental response to human papillomavirus vaccine availability: Uptake and intentions. J Adolesc Health 2009;45:528–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pruitt SL, Schootman M. Geographic disparity, area poverty, and human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:525–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenthal SL, Rupp R, Zimet GD, et al. Uptake of HPV vaccine: Demographics, sexual history and values, parenting style, and vaccine attitudes. J Adolesc Health 2008;43:239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yeganeh N, Curtis D, Kuo A. Factors influencing HPV vaccination status in a Latino population; and parental attitudes towards vaccine mandates. Vaccine 2010;28:4186–4191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, Reiter PL, et al. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in a high-risk geographic area. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:197–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ogilvie G, Anderson M, Marra F, et al. A population-based evaluation of a publicly funded, school-based HPV vaccine program in British Columbia, Canada: Parental factors associated with HPV vaccine receipt. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tan W, Viera AJ, Rowe-West B, et al. The HPV vaccine: Are dosing recommendations being followed? Vaccine 2011;29:2548–2554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dempsey A, Cohn L, Dalton V, Ruffin M. Patient and clinic factors associated with adolescent human papillomavirus vaccine utilization within a university-based health system. Vaccine 2010;28:989–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Widdice LE, Bernstein DI, Leonard AC, Marsolo KA, Kahn JA. Adherence to the HPV vaccine dosing intervals and factors associated with completion of 3 doses. Pediatrics 2011;127:77–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harper DM, Verdenius I, Ratnaraj F, et al. Quantifying clinical HPV4 dose inefficiencies in a safety net population. PLoS One 2013;8:e77961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Verdenius I, Harper DM, Harris GD, et al. Predictors of three dose on-time compliance with HPV4 vaccination in a disadvantaged, underserved, safety net population in the US Midwest. PLoS One 2013;8:E71295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lehtinen M, Paavonen J, Wheeler CM, et al. Overall efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against grade 3 or greater cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 4-Year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Muñoz N, Kjaer SK, Sigurdsson K, et al. Impact of human papillomavirus (HPV)-6/11/16/18 vaccine on all HPV-associated genital diseases in young women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:325–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Petäjä T, Pedersen C, Poder A, et al. Long-term persistence of systemic and mucosal immune response to HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in preteen/adolescent girls and young women. Int J Cancer 2011;129:2147–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smolen KK, Gelinas L, Franzen L, et al. Age of recipient and number of doses differentially impact human B and T cell immune memory responses to HPV vaccination. Vaccine 2012;30:3572–3579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barrere A, Stern JE, Feng Q, Hughes JP, Winer RL. Oncogenic human papillomavirus infections in 18- to 24-year-old female online daters. Sex Transm Dis 2015;42:492–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Markowitz LE, Liu G, Hariri S, Steinau M, Dunne EF, Unger ER. Prevalence of HPV after introduction of the vaccination program in the United States. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20151968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schlecht NF, Diaz A, Shankar V, et al. Risk of delayed HPV vaccination in inner-city adolescent women. J Infect Dis 2016;214:1952–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Coughlin SS. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arnold HJ, Feldman DC. Social desirability response bias in self-report choice situations. Acad Manage J 1981;24:377–385 [Google Scholar]