Abstract

Objectives

Disparities in the global burden of breast cancer have been identified. We aimed to investigate recent patterns and trends in the breast cancer incidence and associated mortality. We also assessed breast cancer-related health inequalities according to socioeconomic development factors.

Design

An observational study based on the Global Burden of Diseases.

Methods

Estimates of breast cancer incidence and mortality during 1990–2016 were obtained from the Global Health Data Exchange database. Subsequently, data obtained in 2016 were described using the age-standardised and age-specific incidence, mortality and mortality-to-incidence (MI) ratios according to sociodemographic index (SDI) levels. Trends were assessed by measuring the annual percent change using the joinpoint regression. The Gini coefficients and concentration indices were used to identify between-country inequalities.

Results

Countries with higher SDI levels had worse disease incidence burdens in 2016, whereas inequalities in the breast cancer incidence had decreased since 1990. Opposite trends were observed in the mortality rates of high and low SDI countries. Moreover, the decreasing concentration indices, some of which became negative, among women aged 15–49 and 50–69 years suggested an increase in the mortality burdens in undeveloped regions. Conversely, inequality related to the MI ratio increased. In 2016, the MI ratios exhibited distinct gradients from high to low SDI regions across all age groups.

Conclusions

The patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality closely correlated with the SDI levels. Our findings highlighted the primary prevention of breast cancer in high SDI countries with a high disease incidence and the development of cost-effective diagnostic and treatment interventions for low SDI countries with poor MI ratios as the two pressing needs in the next decades.

Keywords: breast cancer, mortality-to-incidence ratio, socio-demographic index, Gini coefficient, concentration index

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides the first overview of current global patterns and long-term trends in breast cancer burdens stratified according to sociodemographic development.

The Gini coefficient and concentration index were used to evaluate the extent, trend and concentration of health inequalities caused by breast cancer.

The study was limited by the use of secondary estimated data from the Global Burden of Disease database, as the estimates for some countries with poor-quality raw data may have been biased.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer worldwide and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women, with an estimated 2.4 million new cases and 523 000 deaths reported in 2015.1 A woman’s place of residence and socioeconomic status are significant determinants of the odds of developing breast cancer and the ultimate survival outcome.1 The breast cancer incidence rate is higher in high-income countries than in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).1–3 In many high-income countries, a better awareness of the risk factors, regular mammography screening and sufficient and effective medical services have led to significant decrease in breast cancer mortality rates in recent decades and stable or even decreasing incidence rates since 2000. However, breast cancer is not restricted to high-income countries. The low cancer incidence rates in LMICs have not necessarily translated to lower cancer-related mortality rates.3–5 Both the breast cancer incidence and related mortality have increased in many resource-poor settings or countries, partially due to changes in reproductive patterns and delays in diagnosis and treatment, which are independent of an increase in breast cancer awareness.6 7

Disparities in the global burden of breast cancer have been identified, especially among counties with different levels of development. Global health policy makers rely on understanding of the exact correlations between the disease burden and socioeconomic status to formulate appropriate measures according to local conditions. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation first introduced the sociodemographic index (SDI) in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 (GBD 2015) as a quantitative measure of development in a country or region.8 This study aimed to describe current patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality among countries according to national-level well-being by combining the latest SDI data with breast cancer incidence and mortality data collected between 1990 and 2016. This approach would enable a comprehensive investigation of the distribution of breast cancer-associated health inequalities and related changes according to the level of national development.

Materials and Methods

Breast cancer was defined using code C50 from the International Classification of Disease-Revision, 10th edition. Incidence and mortality data from 195 individual countries across five predefined SDI groups during 1990–2016 were collected from the Global Health Data Exchange database.5 The annual incidence and mortality rates for subjects aged 15 to 95+ years were extracted for each involved country and stratified into 5-year age brackets. Detailed methods for estimating the age-standardised incidence and mortality rates (ASIR and ASMR, respectively) per 100 000 women in a population were described in the GBD 2016 reports.3 4 Women aged 50–69 years comprised the largest population participating in regular screening programmes. We further calculated the age-specific incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 women into three age subgroups: 15–49, 50–69 and 70+ (including 70) years, and these rates were adjusted according to the new world population age-standard.3 The mortality-to-incidence (MI) ratio was calculated by dividing the breast cancer mortality rate for a given year, age group, country and SDI group by the corresponding incidence rate.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in the recruitment and conduct of this study.

SDI

The SDI, a comparable metric of overall development, was calculated using the lag-distributed income per capita, average years of education in the population older than 15 years and total fertility rate, with equal weighting of these variables.9 The SDI is expressed using a scale of 0–1, with a greater value indicating a higher level of development. SDI data from the 195 countries involved in the study during 1990–2016 were obtained from the Global Health Data Exchange database.5 Countries were classified into the following quintiles based on their SDI values in 2016: high, high-middle, middle, low-middle and low SDI. Detailed methods describing the calculation of SDI and the selection of the quintile cutoffs have been previously reported.1 3

Gini coefficient and concentration index

We adopted the Gini coefficient and concentration index, which are used in the field of economics, to measure breast cancer-associated health inequalities in our study.10 11 The Gini coefficient is calculated based on the Lorenz curve. The coefficient ranges between 0 and 1, with 0 and 1 representing perfect equality and total inequality, respectively.11 The annual ASIRs, ASMRs, age-specific incidence rates, age-specific mortality rates and MI ratios of breast cancer from the 195 included countries were used to calculate the Gini coefficients and describe trends in health inequality between countries from 1990 to 2016. The concentration index, which is derived from the concentration curve, is a common measure of socioeconomic-related health inequality.12 The concentration indices were calculated by correlating the above-mentioned breast cancer metrics with the corresponding national SDIs. The concentration index values range between −1 and +1. A positive or negative concentration index value indicated that the breast cancer disease burden was more concentrated in countries with high or low levels of development, respectively, as measured by the SDI.12 The absolute index value was related to the degree of a ‘pro-developed’ or ‘pro-underdeveloped’ distribution of health limitations. A value of zero indicated an absence of inequality associated with the socioeconomic gradient rather than an absolute absence of inequality.

Statistical analyses

We performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by pairwise comparisons with the Tamhane T2 test to compare variables with normal distributions but heterogeneous variances, such as the incidence, mortality and MI ratio, across five SDI-based country groups.13 A linear regression model was used to test the correlations between indicators of the breast cancer burden and the SDI values. A joinpoint piecewise linear regression analysis was performed to identify the time points corresponding to significant changes and identify temporal trends in the age-standardised and age-specific incidence and mortality rates between 1990 and 2016.14 Default parameters were used for all analyses except for the minimum number of data points between two joints or at either end of the data; these two values were set to five. The maximum number of joinpoints was set to two to avoid overfitting at the truncating points. The best-fit point corresponding to a significant change in the rate was assessed using a permutation test and the p value for each test was estimated using Monte Carlo methods.14 Statistics relating to the annual percent change (APC) for each segment and average annual percent change (AAPC) for the overall period were summarised using the optimal joinpoint model. All joinpoint trend analyses were performed using joinpoint statistical software (V.4.5.0.1; Surveillance Research Program of the United States National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA).15 The Gini coefficient and concentration index values were computed using the AINEQUAL16 and CONINDEX modules17 of Stata 14.0 software (Stata, College Station, Texas, USA). Other statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Current profiles in breast cancer incidence and mortality rates according to SDIs

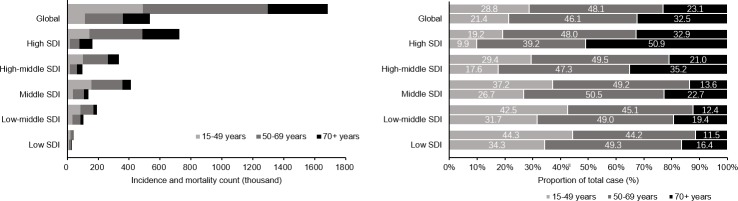

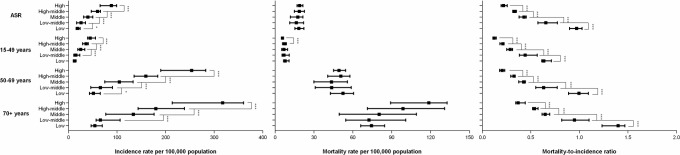

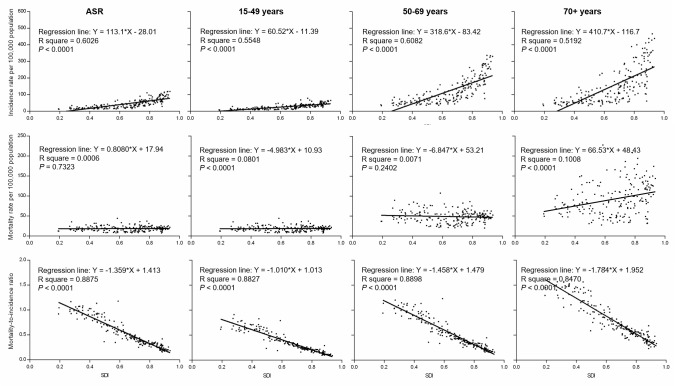

Figure 1 presents the distribution of counts and proportions of new breast cancer cases and related deaths in the 5 SDI groups during the year 2016. Approximately 719 000 new cases were reported in high SDI countries, and this value was about 20 times higher than the 37 000 new cases reported in low SDI countries. Moreover, 162 000 and 32 000 deaths were reported in these groups, respectively. Approximately half of all new breast cancer cases occurred in women aged 50–69 years across all SDI groups. In middle, low-middle and low SDI countries, more than a third of new breast cancer cases were identified in women aged 15–49 years, and this group also had a higher proportion of deaths. In contrast, in high SDI countries, women aged 70+ years accounted for 50.9% of all reported breast cancer-related deaths. One-way ANOVA suggested significant differences in both the age-standardised and age-specific incidence rates and MI ratios (p<0.01) but not in the mortality rates among countries belonging to different SDI groups. Pairwise comparisons showed the mortality rates were not proportional to the corresponding high incidence rates in countries with higher level of development indicated by SDI, and the lowest MI ratios were observed in high SDI countries (figure 2). In all age groups, positive relationships existed between the incidence rates and SDI values and negative relationships existed between the MI ratios and SDI values (figure 3). Moreover, the MI ratios exhibited well-fitting linear relationships in all age groups, whereas the incidence and mortality rates in older age groups were more scattered among countries with different SDIs.

Figure 1.

Distribution of breast cancer incidence and mortality counts and proportions by age at the global level and SDI quintiles in 2016. SDI, sociodemographic index.

Figure 2.

Patterns for breast cancer, in terms of age-standardised and age-specific (A) incidence rates, (B) mortality rates and (C) MI ratios by SDI group in 2016. Black squares represent the medians of all rates from the countries included in each SDI level. Lines denote the IQRs. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. MI, mortality-to-incidence; SDI, sociodemographic index.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the incidence rates, mortality rates, MI ratios and SDI levels by age. The best-fitted line according to linear regression analysis was shown. MI, mortality-to-incidence; SDI, sociodemographic index.

Temporal trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality across SDI groups

According to the joinpoint trend analysis (table 1), the ASIRs in high and high-middle SDI groups plateaued after rapidly increasing in the early 1990s. In the high SDI group, the ASIR even exhibited a declining trend of 0.1% per year since 2000. In contrast, significant increases in the ASIRs were observed in the middle, low-middle and low SDI groups over the whole study period (online supplementary figure 1A). The AAPC in ASIR was 2.1% for the middle SDI group, and this was the highest increase among the SDI groups. The trends in incidence rate changes among women aged 15–49, 50–69 and 70+ years were comparable with the ASIR values across the SDI groups (online supplementary table 1 and online supplementary figure 1B).

Table 1.

Breast cancer age-standardised incidence rates in 1990, 2016 and joinpoint trend analysis between 1990 and 2016 by SDI settings

| 1990 | 2016 | Trend 1 | Trend 2 | Trend 3 | AAPC (%) | ||||||||

| Case | ASR | 95% UI | Case | ASR | 95% UI | Period | APC (%) | Period | APC (%) | Period | APC (%) | ||

| Global | 815.4 | 41.0 | 39.8–43.1 | 1681.9 | 45.6 | 43.6–48.2 | 1990–1995 | 1.5* | 1995–2000 | 0.2* | 2000–2016 | 0.1* | 0.4* |

| High SDI | 463.0 | 83.6 | 82.0–85.1 | 719.4 | 88.9 | 86.5–93.0 | 1990–1995 | 1.3* | 1995–2000 | 0.2* | 2000–2016 | −0.1* | 0.2* |

| High-middle SDI | 153.1 | 37.1 | 36.0–38.6 | 329.0 | 46.5 | 42.9–50.5 | 1990–1995 | 3.2* | 1995–2016 | 0.4* | 0.9* | ||

| Middle SDI | 116.0 | 19.3 | 18.1–22.1 | 408.8 | 33.2 | 30.4–36.0 | 1990–2000 | 2.6* | 2000–2009 | 2.0* | 2009–2016 | 1.5* | 2.1* |

| Low-middle SDI | 69.7 | 17.7 | 14.9–21.9 | 187.0 | 23.1 | 21.1–27.8 | 1990–1999 | 1.3* | 1999–2010 | 0.4* | 2010–2016 | 1.8* | 1* |

| Low SDI | 15.6 | 16.3 | 13.6–20.9 | 37.0 | 18.8 | 17.1–20.8 | 1990–1995 | 0.9* | 1995–2010 | 0.3* | 2010–2016 | 0.8* | 0.5* |

*P<0.05.

AAPC, average annual percent change; APC, annual percent change; ASR, age-standardised rate; SDI, sociodemographic index; 95% UI, 95% uncertainty interval.

bmjopen-2018-028461supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Changes in the ASMR varied across the SDI groups, as shown in table 2 and online supplementary figure 2A. In the high SDI group, the ASMR decreased continuously from 24.2 in 1990 to 17.6 in 2016, with an AAPC of −1.3%. In the high-middle SDI group, the ASMR began to decline in 1994, with an accelerated decrease (APC: −1.9%) between 2004 and 2016. In the middle SDI group, the ASMR also decreased slightly from 2002 to 2016, with an average decrease of 0.5% per year. Opposite trends were observed in the low-middle (2002–2016, APC: 0.7%) and low SDI groups (2009–2016, APC: 0.8%), especially in more recent years. Although the patterns of change in the three age groups were similar to the ASMR in each SDI group, the degrees of change differed among the groups (online supplementary table 2 and online supplementary figure 2B). For example, among subjects aged 70+ years, we observed lesser decreases and greater increases in the mortality rate in more and less developed regions, respectively.

Table 2.

Breast cancer age-standardised mortality rates in 1990, 2016 and joinpoint trend analysis between 1990 and 2016 by SDI settings

| 1990 | 2016 | Trend 1 | Trend 2 | Trend 3 | |||||||||

| Case | ASR | 95% UI | Case | ASR | 95% UI | Period | APC (%) | Period | APC (%) | Period | APC (%) | AAPC (%) | |

| Global | 336.9 | 17.2 | 16.4–18.8 | 535.3 | 14.6 | 13.8–15.6 | 1990–1994 | 0.8* | 1994–2002 | −0.6* | 2002–2016 | −1.1* | −0.7* |

| High SDI | 141.1 | 24.2 | 23.8–24.7 | 162.1 | 17.6 | 16.9–18.3 | 1990–1995 | −0.6* | 1995–2010 | −1.6* | 2010–2016 | −1* | −1.3* |

| High-middle SDI | 65.5 | 15.9 | 15.2–17.0 | 97.9 | 13.7 | 12.2–15.7 | 1990–1994 | 2.9* | 1994–2004 | −0.4* | 2004–2016 | −1.9* | −0.6* |

| Middle SDI | 65.5 | 11.6 | 10.7–13.7 | 138.5 | 11.8 | 10.8–12.7 | 1990–2002 | 0.8* | 2002–2016 | −0.5* | 0.1* | ||

| Low-middle SDI | 50.7 | 13.6 | 11.4–17.3 | 104.5 | 13.8 | 12.1–17.2 | 1990–1999 | 0.7* | 1999–2012 | −0.6* | 2012–2016 | 0.7* | 0 |

| Low SDI | 13.9 | 15.7 | 13.0–20.2 | 31.9 | 17.6 | 15.7–19.9 | 1990–1996 | 0.9* | 1995–2009 | 0 | 2009–2016 | 0.8* | 0.5* |

AAPC, average annual per cent change; APC, annual per cent change; ASR, age-standardised rate; SDI, sociodemographic index; 95% UI, 95% uncertainty interval.

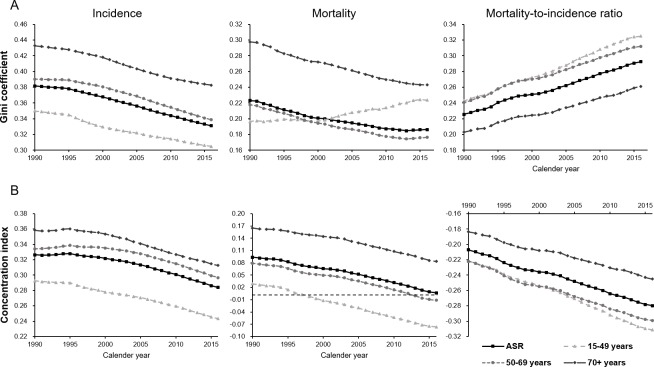

Global health inequality related to breast cancer

The Gini coefficients for the incidence of breast cancer continuously decreased from 1990 to 2016 (figure 4A). The values calculated from the ASIRs and incidence rates among women aged 15–49, 50–69 and 70+ years decreased to 0.33, 0.30, 0.34 and 0.38 by 2016, respectively, from starting values of 0.38, 0.35, 0.39 and 0.43 in 1990, respectively. Similarly, the Gini coefficients calculated using the mortality rates exhibited markedly declining trends over the same period in all age groups, except those aged 15–49 years. In contrast, the Gini coefficients calculated using the age-standardised MI ratio distributions increased, from 0.23 in 1990 to 0.29 in 2016.

Figure 4.

Trends in (A) the Gini coefficients and (B) concentration indices calculated based on health metrics of breast cancer, in terms of age-standardised and age-specific incidence rates, mortality rates and MI ratios, across 195 countries worldwide between 1990 and 2016. MI, mortality-to-incidence.

In 1990, all the concentration indices based on the breast cancer age-standardised and age-specific incidence and mortality rates exceeded zero, suggesting that the inequalities associated with socioeconomic development were more concentrated in countries with higher levels of development (as indicated by SDI). Moreover, the concentration indices were higher among subjects aged 70+ years than in other groups. Both the concentration indices for the incidence and mortality rates decreased between 1990 and 2016, and the rate of decrease began to accelerate in the late 1990s (figure 4B). The concentration indices for mortality rates in the age groups of 15–49 and 50–69 years decreased below zero and became negative in 1998 and 2013, respectively. In contrast, the concentration indices based on age-standardised MI ratios and age-specific rate ratios for age groups of 15–49, 50–69 and 70+ years were already below zero in 1990, with values of -0.21,–0.22, −0.22 and −0.18, respectively. By 2016, these values had decreased to –0.28, –0.31, −0.30 and −0.25, respectively.

Discussion

Socioeconomic development-associated inequalities in the global incidence of breast cancer have continued to decrease since 1990. However, countries with higher levels of development according to the SDI reported a worse burden of breast cancer incidence by 2016. Consistent with the opposite trends in mortality rates between countries with high and low SDI values, the mortality concentration indices among women aged 15–49 and 50–69 years have become negative in recent years. This phenomenon suggests a shift in the concentration of the mortality burden from developed to undeveloped countries. Conversely, both the overall inequality and inequality associated with socioeconomic development, which was calculated using the MI ratio, increased from 1990 to 2016. In 2016, the MI ratio distribution exhibited a distinct gradient from high to low SDI countries across all age groups.

The availability of epidemiological data from individual countries has led to a prevailing perception that inequalities exist in the global breast cancer incidence, especially between high-income countries and LMICs.18–21 However, there remains a paucity of quantitative evidence regarding the relationship between the global breast cancer burden and national levels of socioeconomic development. According to the GLOBOCAN 2012 estimates, the breast cancer incidence burden was distributed among countries at different human development index (HDI) levels, with obvious disparities.2 The results of that report are consistent with our results, which were based on the SDI and data from the GBD 2016 study. We observed that the overall inequality in the breast cancer incidence had not yet been eliminated and remained concentrated in countries with high SDI levels. This higher prevalence of breast cancer is somewhat associated with the so-called western lifestyle (ie, specific reproductive patterns and excessive body weight),22 23 and thus can be used as a marker of the extent of development. Our trend analyses demonstrated rapid increases in the breast cancer incidence rates of countries classified in the middle SDI group. This result suggests that countries with SDI levels near the middle of the spectrum were undergoing rapid social and economic changes during the study period.24 In many LMICs, the burdens of infection-related cancers, including cervical, gastric and liver cancer, remained higher than those of breast cancer.1 2 Moreover, high-income countries have generally implemented mammographic screening programmes, especially for women aged 50–69 years.25–27 Consistently, our age-based subgroup analysis confirmed a transient increase in the incidence of breast cancer among women aged 50–69 years and a subsequent decrease among those aged 70+ years in countries with high SDI values.

The mortality rates did not differ significantly between low and high SDI countries. Inequalities in breast cancer deaths were possibly offset by better clinical outcomes in more developed countries due to early diagnosis and the development of advanced treatments; in contrast, the situation in most LMICs were characterised by a low incidence of breast cancer but limited access to healthcare services.28 29 Therefore, the mortality rates do not represent the exact trends and current statuses of the burdens of cancer-related death. Cancer survival is another important indicator used to evaluate the malignancy-related death burden. According to data from 59 countries in the CONCORD-2 study,30 the 5-year survival rates of patients diagnosed with breast cancer during 2005–2009 were ≥85% in North America, Australia, Israel, Brazil and most Northern and Western European countries but ≤60% in many LMICs, such as India, Mongolia, Algeria and South Africa. However, little comprehensive survival data were available from most countries, especially those with limited resources. Accordingly, the determination of the effects of socioeconomic development-associated inequalities on the survival rates of patients with breast cancer and comparisons of current survival statuses among various countries across the world remained critical issues. In this study, we analysed the trends in inequality of the breast cancer MI ratio, a marker used to estimate the extent to which actual mortality differs from the expected mortality relative to disease incidence; the marker has been suggested as an approximation of cancer survival.31–33 Our results suggest increasing disparities according to breast cancer MI ratios among countries with different levels of development.

The HDI, a metric comprising the life expectancy at birth, mean and expected years of education and gross national income per capita,34 was used to investigate the correlations between macro-socioeconomic determinants and national disease burdens.2 28 35 However, this index is not ideal for evaluating the effects of socioeconomic development on health because the measure relies on the overall health (i.e., life expectancy at birth), which could introduce bias. The SDI was initially developed in the GBD 2015 study, to determine the placement of countries or geographic areas on the spectrum of social development.8 Given the role of reproductive patterns as risk factors for breast cancer,22 the SDI, a measure based on measures of income, education and fertility rate, might be more appropriate than the HDI when assessing the degree of influence of the socioeconomic status on global patterns and trends in health inequality associated with breast cancer.

To our knowledge, this study provides the first overview of global patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality according to the SDI. However, our results should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, this study is subject to the limitations of the GBD 2016 study such as the data sources and statistical assumptions, as detailed in the related reports.3 4 For most LMICs, the estimates, particularly the MI ratios, might have been biased due to poor-quality raw data. Future studies will require better primary data from nation-wide observational studies or cancer registries. Second, the joinpoint analysis is particularly sensitive to parameter settings. Accordingly, trends in the patterns of incidence and mortality may change if the parameters are changed or more data are analysed. Third, the GBD 2016 database did not provide regional data within each country or information about disease stages and histopathological characteristics. In the USA, for example, nation-wide distributions and trends in breast cancer burden can differ by ethnicity, state, disease stage and intrinsic subtype.36 37 Therefore, more studies are needed to understand the global disparities more fully and to eliminate biases in the data.

Conclusion

The patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality closely correlated with the SDI levels. The health inequality associated with the breast cancer incidence according to the SDI had been decreasing since 1990. Countries with middle-level SDI values, which may have been experiencing shifts in economic and lifestyle factors, exhibited increasing incidence rates of breast cancer. Nonetheless, the incidence burden in 2016 remained more concentrated in countries with higher SDI levels. These findings emphasise that public health clinicians and cancer control specialists should pay more attention to the primary prevention of breast cancer, especially in most developed countries with high incidence. In low-middle and low SDI countries, the actual breast cancer mortality rates differed greatly from the expected mortality rates based on the corresponding low incidence rates. Public health planners should implement more sensitive and cost-effective detection and treatment interventions to counteract the premature deaths caused by breast cancer, particularly in less developed countries with limited healthcare resources.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Footnotes

KH and PD contributed equally.

Contributors: KH designed the study, extracted and analysed the data and prepared the figures. PD and YW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TP and WT revised the paper critically. SZ was the principle investigator and designed the study. All authors commented on manuscript drafts and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 81602716 and 81802628).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was not obtained because the data included in this study were publicly available.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The data used in this study are collected from the Global Health Data Exchange database. Available from: h ttp://www.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

References

- 1. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. . Global, regional, and National cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and Disability-Adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:524–48. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ginsburg O, Bray F, Coleman MP, et al. . The global burden of women’s cancers: a grand challenge in global health. The Lancet 2017;389:847–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31392-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Disease GBD, Injury I, Global PC, et al. . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1151–210. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Global Health Data Exchange GBD results tool. Available: http://www.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool [Accessed 26 Sep 2017].

- 6. Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Dunn NAM, et al. . The descriptive epidemiology of female breast cancer: an international comparison of screening, incidence, survival and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol 2012;36:237–48. 10.1016/j.canep.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Torre LA, Islami F, Siegel RL, et al. . Global cancer in women: burden and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:444–57. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1459–544. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network Global burden of disease study 2016 (GBD 2016) socio-demographic index (SDI) 1970–2016. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bleichrodt H, van Doorslaer E. A welfare economics foundation for health inequality measurement. J Health Econ 2006;25:945–57. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pan American Health Organization Measuring health inequalities: Gini coefficient and concentration index. Epidemiol Bull 2001;22 10.1109/HICSS.2003.1174353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Costa-Font J, Hernández-Quevedo C. Measuring inequalities in health: what do we know? what do we need to know? Health Policy 2012;106:195–206. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shingala MC, Rajyaguru A. Comparison of post hoc tests for unequal variance. Int j new technol sci eng 2015;2:22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. . Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19:335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Insititute NC. Surveillance Epidemiology and end results (SEER) program. methods & tools: joinpoint trend analysis. Available: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint [Accessed 10 Oct 2017].

- 16. Kerm PV. INEQUAL7: Stata module to compute measures of inequality In: Statistical Software Components S416401, Boston College Department of Economics, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Donnell O, O'Neill S, Van Ourti T, et al. . conindex: estimation of concentration indices. Stata J 2016;16:112–38. 10.1177/1536867X1601600112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, et al. . Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:52–62. 10.3322/caac.21203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lundqvist A, Andersson E, Ahlberg I, et al. . Socioeconomic inequalities in breast cancer incidence and mortality in Europe-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health 2016;26:804–13. 10.1093/eurpub/ckw070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li T, Mello-Thoms C, Brennan PC. Descriptive epidemiology of breast cancer in China: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016;159:395–406. 10.1007/s10549-016-3947-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lukong KE, Ogunbolude Y, Kamdem JP. Breast cancer in Africa: prevalence, treatment options, herbal medicines, and socioeconomic determinants. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;166:351–65. 10.1007/s10549-017-4408-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Porter P. "Westernizing" women's risks? Breast cancer in lower-income countries. N Engl J Med 2008;358:213–6. 10.1056/NEJMp0708307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lahmann PH, Schulz M, Hoffmann K, et al. . Long-Term weight change and breast cancer risk: the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC). Br J Cancer 2005;93:582–9. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bray F. Transitions in human development and the global cancer burden : Steward BW, Wild CP, World cancer report 2014. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gøtzsche PC, Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;156 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Narod SA. Reflections on screening mammography and the early detection of breast cancer: a Countercurrents series. Curr Oncol 2014;21:210–4. 10.3747/co.21.2068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Løberg M, Lousdal ML, Bretthauer M, et al. . Benefits and harms of mammography screening. Breast Cancer Res 2015;17 10.1186/s13058-015-0525-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, et al. . Global cancer transitions according to the human development index (2008-2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:790–801. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70211-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Coughlin SS, Ekwueme DU. Breast cancer as a global health concern. Cancer Epidemiol 2009;33:315–8. 10.1016/j.canep.2009.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H, et al. . Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995–2009: analysis of individual data for 25 676 887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2). The Lancet 2015;385:977–1010. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62038-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. JCO 2006;24:2137–50. 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parkin DM, Bray F. Evaluation of data quality in the cancer registry: principles and methods Part II. completeness. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:756–64. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Asadzadeh Vostakolaei F, Karim-Kos HE, Janssen-Heijnen MLG, et al. . The validity of the mortality to incidence ratio as a proxy for site-specific cancer survival. Eur J Public Health 2011;21:573–7. 10.1093/eurpub/ckq120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Programme UND. Human development report. Available: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi [Accessed 16 Nov 2017].

- 35. Fidler MM, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. A global view on cancer incidence and national levels of the human development index. Int J Cancer 2016;139:2436–46. 10.1002/ijc.30382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Goding Sauer A, et al. . Breast cancer statistics, 2015: convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:31–42. 10.3322/caac.21320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. DeSantis CE, Ma J, Goding Sauer A, et al. . Breast cancer statistics, 2017, racial disparity in mortality by state. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:439–48. 10.3322/caac.21412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028461supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)